Abstract

In this work, we investigate the use of a three-stage Compton camera to measure secondary prompt gamma rays emitted from patients treated with proton beam radiotherapy. The purpose of this study was (1) to develop an optimal three-stage Compton camera specifically designed to measure prompt gamma rays emitted from tissue and (2) to determine the feasibility of using this optimized Compton camera design to measure and image prompt gamma rays emitted during proton beam irradiation. The three-stage Compton camera was modeled in Geant4 as three high-purity germanium detector stages arranged in parallel-plane geometry. Initially, an isotropic gamma source ranging from 0 to 15 MeV was used to determine lateral width and thickness of the detector stages that provided the optimal detection efficiency. Then, the gamma source was replaced by a proton beam irradiating a tissue phantom to calculate the overall efficiency of the optimized camera for detecting emitted prompt gammas. The overall calculated efficiencies varied from ~10−6 to 10−3 prompt gammas detected per proton incident on the tissue phantom for several variations of the optimal camera design studied. Based on the overall efficiency results, we believe it feasible that a three-stage Compton camera could detect a sufficient number of prompt gammas to allow measurement and imaging of prompt gamma emission during proton radiotherapy.

1. Introduction

The goal of radiotherapy is to ensure local tumor control by delivering a prescribed dose of radiation to cancerous tissues while minimizing radiation-induced side effects in surrounding healthy tissue. The overall clinical outcome of radiotherapy depends strongly on not only the accuracy of treatment delivery, but also the tumor's response to the radiation. Advances in radiotherapy, such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy and proton radiotherapy, have been specifically developed to improve treatment accuracy and conformality. However, the effectiveness of modern radiotherapy remains limited by uncertainties arising from changes in patient anatomy and a lack of understanding of tissues’ biological responses to various types of radiotherapy. Proton beam radiotherapy, with its well-defined dose deposition, has proven effective in delivering highly conformal radiation dose to a tumor volume while minimizing dose to surrounding healthy tissues and organs. However, in proton therapy, determining the exact position at which the proton beam stops (i.e. location of the distal edge of the Bragg peak) in the face of changing patient anatomy and daily setup uncertainties is often the most uncertain parameter (ICRU 1993).

Since protons stop in the patient, they are not available for measurement at the exit of the patient using portal imaging devices, such as is common with x-ray therapy. Therefore new methods of determining in vivo dose delivery must be developed. One suggested method is to measure the secondary radiation emitted from the patient during beam delivery. For instance, secondary gamma rays emitted from the patient have been studied as one possible candidate for in vivo imaging of the dose delivered to the patient (Testa et al 2008, Min et al 2006, Vynckier et al 1993). The two main sources of secondary gamma rays are (1) through emission of coincident gamma rays from the annihilation of positrons produced from beta+ decaying nuclei created during proton irradiation, known as ‘delayed emission’, or (2) through the direct emission of characteristic gamma rays from an excited nucleus, known as ‘prompt emission’. Over the past decade, there has been a lot of work done on dose verification using PET imaging techniques to measure the delayed gamma signal from positron emitters created during irradiation (Knopf et al 2009,Nishio et al 2005, Parodi et al 2002).

Additionally, several researchers have recently begun to investigate the use of characteristic prompt gamma rays emitted as a means of verifying proton dose delivery (Min et al 2006, Polf et al 2009a, Styczynski et al 2009). Characteristic prompt gamma rays emitted from tissue during proton irradiation typically range in energy from 2 MeV up to 15 MeV (Polf et al 2009a). Due to their energy, it is not possible to produce an image of prompt gamma ray emission using a standard, two-dimensional (2D) collimated imaging system, such as with modern SPECT imaging. Such techniques rely on physical collimation of the gamma rays as a means of producing images. However, to collimate a 7 MeV characteristic gamma ray from oxygen for instance, thicker than 10 cm of lead is required, making it impractical due to the corresponding weight and size of such a device. Additionally, gamma rays in this energy range will often Compton scatter several times within the collimator and detector, thus increasing the background signal in the reconstructed images. Therefore, to measure the energy and spatial characteristics needed for imaging, a method of detecting the prompt gamma rays from tissue must be used that does not rely on traditional 2D collimation or complete absorption of the gamma rays.

One possible method for prompt gamma ray detection is the ‘Compton camera’, which does not require 2D collimation or total absorption of the characteristic gamma rays in order to produce images. The Compton camera is a multi-stage measurement device capable of determining the initial energy and direction of a gamma ray as it Compton scatters in the different stages of the detectors. The Compton camera has been successfully used in high-energy applications, such as astrophysics (Deleplanque et al 1999, Schmid et al 1999)aswellas lower-energy applications such as nuclear imaging (Ordonez et al 1999, Singh 1983). Several research groups have studied the use of a two-stage Compton camera for the measurement of prompt gamma rays as a means of verifying the proton beam range during patient treatment (Frandes et al 2010, Kang and Kim 2009, Takada et al 2005). These two-stage cameras relied on full absorption of the gamma ray to determine its initial energy. However, these devices showed poor intrinsic measurement efficiency for gamma rays above 2 MeV (Takada et al 2005) due to reduced efficiency for completely absorbing higher energy gamma rays. This fact limits the usefulness of these current two-stage designs for measuring the spectra of characteristic prompt gamma rays (2–15 MeV) emitted from tissue.

As a result, several researchers have proposed the application of the three-stage Compton camera (Richard et al 2009, Kroeger et al 2002, Kurfess et al 2000), which does not rely on full absorption of the gamma ray in order to determine the initial spatial and energy information necessary for image reconstruction, thus making it more suited for measurement and imaging of characteristic gamma rays emitted from tissue. In particular, Richard et al (2009) investigated the use of a three-stage camera designed for high energy physics applications. They concluded that the intrinsic measurement efficiency of their Compton camera, originally designed for measuring lower energy gammas, was too low to be useful as an imaging device during charged particle radiotherapy. Therefore, we believe that before a three-stage Compton camera can be used for measuring and imaging prompt gamma ray emission during hadron therapy, its design must first be optimized for such an application.

Therefore, in this paper we present a novel, theoretical design study of a three-stage Compton camera, optimizing its detection efficiency specifically for prompt gamma rays in the 2–15 MeV energy range. While the design and physical construction of a clinically viable Compton camera imaging system is the ultimate, long-term goal of this project, we believe that a design study of optimal detection efficiency for such a system represents a logical ‘first step’ in the realization of this goal. We note that detection efficiency is only one of several figures-of-merit for determining the ultimate clinical usefulness of such a system. Many other issues, such as limitations in resolution for measuring the gamma scattering angle, ability to correctly measure and process the correct sequence of gamma interactions in the detector, considerations related to proper cooling and biasing of the detectors, etc, will all contribute to determining the ultimate feasibility of a Compton camera. The in-depth studies of these and other important features (i.e. shielding, signal processing, and image resolution and reconstruction) of a clinical imaging system will be left to future work and will therefore only be briefly and qualitatively discussed.

For this study, we specifically aim to accomplish two objectives: (1) to develop an optimal three-stage Compton camera specifically designed for measuring characteristic prompt gamma rays emitted from tissue and (2) to determine the feasibility of using the three-stage Compton camera to image prompt gamma rays produced during proton beam treatment delivery. First, to optimize the Compton camera geometry, we investigated the detection efficiency of each of the three detector stages using a Monte Carlo model of the camera geometry with an isotropic gamma source. The thickness and width of each detector stage, as well as the distance between each detector stage, was varied to maximize the three-stage detection efficiency of the Compton camera. Second, to determine the feasibility of using a Compton camera to measure prompt gammas, we tracked the gamma rays produced by a proton source irradiating a tissue phantom, counting the total number of prompt gamma rays detected using the optimal Compton camera design. These results provided an approximation for the overall efficiency of measuring and imaging prompt gammas during proton beam irradiation of a patient during a typical proton radiotherapy treatment.

2. Materials and methods

In this study, we investigate the intrinsic detection efficiency for a three-stage Compton camera composed of three high-purity germanium detection stages. Germanium crystals can be produced in a wide variety of sizes and shapes and can be segmented in two and three dimensions to provide a method of determining the location of interaction within the crystal. When properly cooled (usually to ~77 K), high-purity germanium crystals have shown excellent energy resolution and have shown the ability to measure x-rays and gamma rays with energies ranging from less than 1 keV up to 10 MeV and higher. Due to these properties, high-purity germanium detectors are used in a wide variety of applications ranging from high energy physics to homeland security.

2.1. Three-stage Compton camera

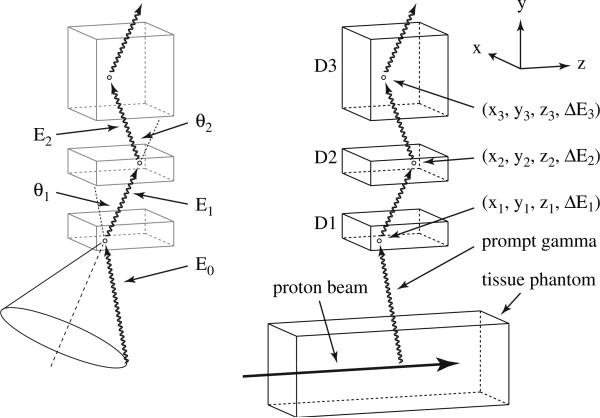

The basic elements of the three-stage Compton camera are a series of three position and energy sensitive detection stages arranged to measure three or more interactions that are used to determine the direction and energy of an incident gamma ray. Each detection stage contains either 2D or 3D spatial segmentation to provide the position at which the interaction occurs within the stage. A typical three-stage Compton camera consists of three stacked detector stages, as shown in figure 1, to capture three consecutive interactions as a means of determining the initial direction of the gamma ray using the Compton scattering equation

| (1) |

where θ1 is the Compton scattering angle of the incident prompt gamma ray, E0 is the energy of the initial gamma ray, E1 is the remaining energy of the gamma ray after the Compton scatter, where E1 = E0 − ΔE1, and ΔE1 is the energy deposited by the gamma ray due to a Compton scatter interaction in the first detector stage. As the gamma ray passes through the Compton camera, it interacts in each of the three stages, giving a position and energy deposited for each interaction. To produce an event which is usable for Compton imaging, the gamma ray must interact a minimum of three times in the detector, referred to as a ‘triple-scatter’ event. The necessary three interactions consist of a single Compton scatter in the first detector stage (D1), a single Compton scatter in the second detector stage (D2) and any interaction (Compton scatter, photoelectric absorption, or pair production) in the third detector stage (D3) in which the position of the interaction is measured. The interaction positions in D2 and D3 determine the second scattering angle (θ2) as shown in figure 1. The energy deposited in the first two interactions (ΔE1, ΔE2) and the second scattering angle (θ2) can then be used to find the energy of the incident prompt gamma ray using the equation

| (2) |

It is then possible to plug the calculated initial gamma ray energy (E0) into equation (1) to determine θ1. As shown in figure 1, the Compton scattering angle of the first interaction and the positions of the Compton scatter events in the first and second detectors are used to determine the direction of the original prompt gamma ray. Tracing the scattered gamma ray from the first interaction (figure 1, dashed line) back toward the source, supplies the central axis of a ‘source cone’, whereas θ1 provides the cone's half-angle which encompasses the cone's central axis. The surface of this source cone represents the possible original path of the gamma ray as determined by its scattering path in the Compton camera. Projecting the cone back to the source produces a ring (solid circle in figure 1) on which the initial prompt gamma ray originated. The superposition of the rings created by many gamma ray triple scatters can then be used to reconstruct an image of the gamma source.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the 3-stage Compton camera setup in parallel-plane geometry showing (on left) the Compton scatter angles (θ1, θ2) and the gamma ray energy (E0, E1, E2) as it travels through the detectors (D1, D2, D3), as well as the projected cone used to reconstruct the images. On the right, an identical Compton camera setup with the prompt gamma originating from a proton beam irradiating a tissue phantom producing a prompt gamma ray that subsequently interacts in the Compton camera with the interaction position and energy deposition in each detector shown.

2.2. Monte Carlo simulation

The Monte Carlo model used for this study was developed using Geant4 (version 9.1), a Monte Carlo toolkit composed of C++ libraries (Agostinelli et al 2003), and adapted from a validated model of a clinical proton beam scanning nozzle (Peterson et al 2009). For this work, the physics models used for the simulations were identical to those used in Peterson et al. (2009). The physics processes most relevant to this work are the elastic and inelastic scattering processes, which cover the proton-nucleus interactions and prompt gamma emission. A complete discussion of the implementation and validation of the model used in this work can be found in Peterson et al (2009) and Polf et al (2009b).

To study detection efficiency for the three-stage Compton camera, we modeled three high-purity germanium detectors arranged in parallel-plane geometry as shown in figure 1. The Compton camera included a fixed 5 cm separation distance between each stage, and the first detector stage (D1) was placed at a distance of 10 cm from the upper edge of a 10 cm × 10 cm × 40 cm tissue phantom, with all space between each detector stage and the phantom filled with air. To study the efficiency with which the modeled Compton camera could measure prompt gamma rays, two different sources of gamma rays were used in the Monte Carlo model: (1) a simple mono-energetic, isotropic gamma ray source, and (2) a proton beam irradiating a tissue phantom producing a spectrum of characteristic prompt gamma rays along the range of the beam within the phantom. First, the isotropic gamma ray point source was placed at the origin of our model (with no tissue phantom present) directly below the modeled Compton camera. This simple source was used to model the emission of prompt gamma rays from an individual nucleus excited by inelastic proton-nuclear scattering during proton beam irradiation. With the isotropic gamma source, we studied the modeled Compton camera response over a range of discrete gamma ray energies ranging from 0 MeV up to 15 MeV. Also, we considered detector response to specific characteristic gamma rays emitted from excited nuclei of several elemental components of soft tissue (ICRU 2000), namely nitrogen (2.31 MeV), carbon (4.44 MeV) and oxygen (6.13 MeV). Second, the tissue phantom (shown in figure 1) was inserted into the model, and a narrow proton ‘pencil’ beam was used to irradiate the phantom, with a range of typical treatment energies (50–250 MeV). These studies were then used to evaluate the overall efficiency of the optimized three-stage detector geometry for measuring prompt gamma rays emitted during proton treatment delivery. Since the prompt gamma ray emission cross section is known to be dependent on proton energy and thus depth within the phantom (Polf et al 2009a, NNDC 2007), for each proton energy, the phantom was positioned so that the center of the Compton camera was located at a depth corresponding to the maximum prompt gamma ray emission cross section (approximately 6 mm proximal to the Bragg peak (Polf et al 2009a)). This ensured that the Compton camera was always centered at the point of maximum prompt gamma emission rate no matter the initial beam energy.

Collecting the data required to study the detection efficiency of the modeled Compton camera starts when the prompt gamma ray is incident on the front face of D1. As the gamma ray travels through the Compton camera, there are six sequential steps leading to a triple scatter event.

The gamma ray enters D1.

The gamma ray single-Compton scatters in D1 (1st scatter).

The scattered gamma ray exits D1 and enters D2.

The scattered gamma ray single-Compton scatters in D2 (2nd scatter).

The scattered gamma ray exits D2 and enters D3.

The scattered gamma ray interacts in D3 (3rd scatter).

During the simulation, each gamma ray is ‘tagged’ with two indicators each time one of the six triple scatter steps occurs. The first indicator represents which of the steps has occurred and the second indicates the order in which the triple scatter step has occurred during the tracking of the gamma ray. In order for the interaction of an individual gamma to be considered a triple scatter event by the MC model, all six steps must occur in order as listed above during the tracking of a given gamma ray history. At the end of each gamma ray history, the detector interaction tags for steps 1–6 were recorded, using ROOT (Brun and Rademakers 1997), in a ‘count’ histogram.

2.3. Detector efficiency

Optimization of the Compton camera was conducted by determining the maximum detection efficiency of each detector stage as a function of the detector dimensions. To find the maximum efficiency of measuring a triple scatter interaction we began by optimizing each detector stage separately, starting with D1 and continuing to D3. For each detector stage, the detection efficiency was investigated by varying the thickness (y-direction in figure 1) from 1 to 20 cm and the lateral dimensions (x- and z-directions in figure 1) from 2.5 to 500 cm. The energy dependence of the detection efficiency was also analyzed by changing the energy of the isotropic gamma source from 0 to 15 MeV in 0.1 MeV increments as well as investigating the energies (2.31, 4.44 and 6.13 MeV) from three characteristic prompt gamma rays emitted from tissue. Once the maximum detection efficiency was determined for each stage, we then determined if the lateral dimensions and thickness values of the optimal detector stage were ‘practical’. That is, could a detector stage of high purity segmented germanium with these dimensions be easily manufactured? If a detector stage with the optimal dimensions was not feasible (i.e. infinite lateral dimensions), then the largest ‘practical’ (or commercially available2 ) dimensions were chosen for that stage and used for the optimization of subsequent detector stages. After the optimal dimensions of a practical Compton camera were determined, we then studied how the efficiency of a Compton camera would increase if the dimensions were allowed to increase beyond that which is currently feasible to manufacture and commercially available.

To calculate the optimal detection efficiency for each detector stage, we determined which of the six sequential steps toward a complete triple scatter interaction were impacted by changing the dimensions of each stage. For the optimization study, the efficiency values are broken up into two categories, transport efficiencies , transport of the gamma from detector m to detector n, and interaction efficiencies , interaction of the gamma inside of detector n, with each detector stage having one of each efficiency type.

For D1, the first three steps of the triple scatter process (described in section 2.2) were impacted by changing the D1 thickness and width. The first step is the gamma ray fluence entering D1 (Fenter1). The second step is a single-Compton scatter interaction (Isc1) by the gamma ray in D1. The third step, which does not occur in D1, is the scattered gamma ray entering D2 after it has single-Compton scattered in D1, or the fluence of Isc1 entering D2 (Fsc1enter2). These three quantities together produce the detection efficiency values used to optimize the dimensions of D1. The D1 transport efficiency from the gamma source is , where Nprompt is the number of emitted prompt gamma rays. The D1 interaction efficiency is , which counts the number of single-Compton scatter interactions that occur in D1 per entering gamma ray. The third efficiency impacted by the changing D1 dimensions is the D2 transport efficiency, , or the number of single-Compton scattered gamma rays in D1 that enter D2 (Fsc1enter2) per Isc1. These three efficiency values were maximized in order to optimize D1. Specifically, the optimal width of D1 was determined by maximizing and the optimal thickness by maximizing and . Once the dimensions of D1 were optimized, the process was repeated with the second detector.

As the D2 dimensions changed, three of the six steps toward the triple scatter interaction were impacted: steps 3–5. The third step is the fluence of Isc1 entering D2 (Fsc1enter2). The fourth step is a single-Compton scatter in D2 by a scattered gamma ray which single-Compton scattered in D1, or a ‘double-Compton’ interaction (Idc2), with our model programmed to ensure the two single-Compton interactions do not occur in the same detector. The fifth step is the scattered gamma ray leaving D2 after a double-Compton interaction and entering D3 without any other interaction occurring, i.e. the fluence of Idc2 entering D3 (Fdc2enter3). These quantities produce the three detection efficiency values used to determine the optimal dimensions for D2. The first quantity, the D2 transport efficiency , was described above. Next, the D2 interaction efficiency is , which counts the number of double-Compton interactions that occur per entering single-Compton scattered gamma ray. Lastly, the D3 transport efficiency, which is dependent on the D2 dimensions, is or the number of gammas that Compton scatter only once in D1, then Compton scatter once in D2, and finally enter D3. The optimization of D2 depended on these three efficiency values with determining the optimal D2 width, and the optimal thickness of D2 found by maximizing and . Once the D2 dimensions were set, the third detector stage dimensions were ready to be optimized.

The third stage was only dependant on triple-scatter interaction steps five and six. The fifth step, described above, is the fluence of Idc2 entering D3 (Fdc2enter3) and the sixth step is any interaction in D3 (following Compton interactions in D1 and D2), or the triple scatter interaction (Its3). These two steps result in two detection efficiency values that determine the dimensions of D3: and . The D3 transport efficiency is similar to that used for optimization of D2 and the D3 interaction efficiency, namely , which counts the number of triple-scatter interactions per double-Compton scattered gamma rays entering D3. and were used to optimize the D3 dimensions with determining the D3 width and determining the D3 thickness, setting the D3 dimensions, thus finalizing the three-stage Compton camera optimization process.

Combining all of the six efficiency values produces the overall efficiency of the camera with an isotropic gamma source or the number of triple-scatter interactions per number of prompt gammas produced by the isotropic source,

| (3) |

After the width and thicknesses of the three detecting stages of the Compton camera were determined, the additional geometric parameter of detector spacing was investigated. Starting with the inter-stage distance between D1 and D2, the spacing was changed from 1 to 10 cm while the distance between D2 and D3 was held constant at 5 cm. Then the D2–D3 inter-stage distance was changed over the same range with the D1–D2 distance held constant at 5 cm. Next, both detector gaps (D1–D2 and D2–D3) were varied from 1 to 10 cm at the same time. Finally, the distance between the front of the Compton Camera (front face of D1) and the tissue phantom was varied from 5 to 40 cm.

Once the detector stage dimensions and spacing of an optimal camera were determined using the isotropic gamma source, the practical camera design was used to estimate the efficiency of detecting characteristic prompt gamma rays produced during proton beam irradiation, which we label as the overall proton source efficiency . The isotropic gamma source was removed and replaced by the proton source and tissue phantom. The proton beam, traveling along the z-direction (as shown in figure 1), with energy varying from 50 to 250 MeV, interacted within the tissue phantom and created prompt gammas that were incident on the optimized Compton camera configuration. All of the detection efficiency values discussed above were used to calculate the overall proton detection efficiency during proton irradiation with the addition of one final step, the determination of the number of prompt gammas emitted (Nprompt) per incident proton (Nproton). So, combining all these variables gives

| (4) |

providing an estimate of the efficiency of measuring prompt gammas per proton incident on the tissue phantom.

3. Results and discussion

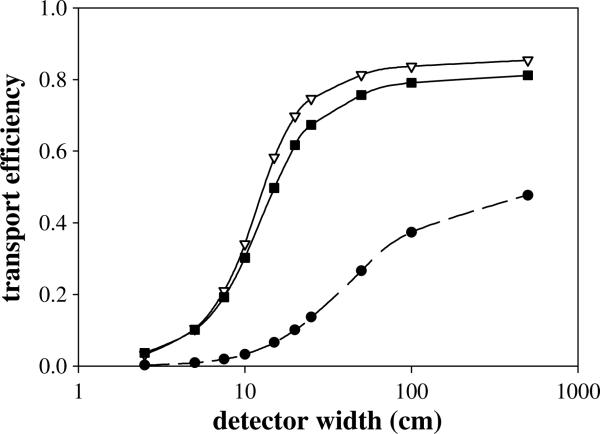

The results for optimizing the detection efficiency of D1 are shown in figures 2 and 3 where changing the widths and thicknesses demonstrates their impact on the related efficiency values . As discussed above, the primary factor in determining the optimal first detector width is the D1 transportation efficiency . Figure 2 shows as a function of D1 width (w1). For the isotropic gamma source, is independent of gamma energy and detector thickness and due to the isotropic nature of the gamma ray point source, follows the solid angle (Ω) relationship for a square plane detector as given by

| (5) |

where d is the distance from the source to D1 (y direction). The results from figure 2 show that increases with w1, over the range of thicknesses studied. Since the maximum value occurs for an impractical detector width (>1000 cm), a more practical and commercially available2 width of 10 cm was chosen for the D1 width for our ‘practical’ camera to be used in the optimization studies of the second and third detectors.

Figure 2.

Transport efficiencies for all three detector stages, D1 (•), D2 (∇) and D3 (■) as a function of their respective widths at initial gamma energy of 6.13 MeV. The D1 transport efficiency is the percentage of prompt gammas that enter D1, shown with a data fit (dashed line) using the solid angle equation (5) at a distance of 15 cm from the source. The calculated transport efficiencies were found to be independent of thickness for all three detector stages. Therefore an arbitrary thickness of 3 cm was set for all three stages.

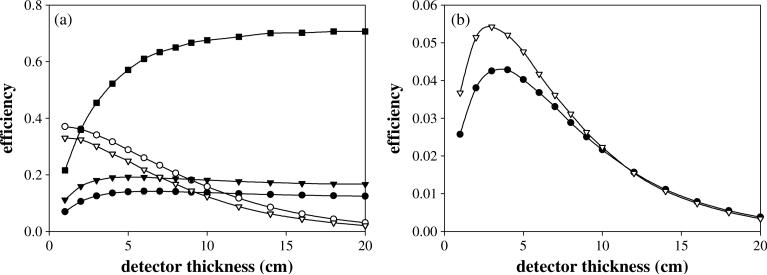

Figure 3.

(a) The interaction efficiencies (solid symbols) and transport efficiencies (empty symbols) for all three detector stages, D1 (circles), D2 (triangles) and D3 (squares) as a function of their respective thicknesses at initial gamma energy of 6.13 MeV. (b) The product of (•) and (∇) as function of detector thickness at initial gamma energy of 6.13 MeV. The detector width for each stage was set to a ‘practical’ value of 10 cm.

To determine the D1 thickness that maximizes the detecting efficiency of the first detector, both the D1 interaction efficiency and the D2 transport efficiency must be considered. Figure 3(a) shows how both these efficiencies relate to the first detector thickness (t1). The D1 interaction efficiency (solid circles in figure 3(a)), initially increases with t1, reaches a maximum value, and then decreases as t1 continues to increase. This behavior can be explained by the fact that single Compton scatter interactions within D1 initially increase with increasing thickness. However, as the thickness continues to increase, the incidence of multiple gamma interactions within D1 becomes more prevalent, causing a decrease in the number of gamma rays that Compton scatter only once in the detector.

The value of (open circles in figure 3(a)) steadily decreases as t1 increases. This is primarily a result of the 5 cm fixed detector spacing used in the simulations. As t1 increases with the D1–D2 spacing fixed, D2 moves incrementally further away from D1, producing a geometric disadvantage with fewer D1 single Compton-scattered gammas hitting D2. Since both and depend on t1, their values were multiplied together to determine optimal thickness. The resulting combined efficiency (circles in figure 3(b)) produces a maximum value at thicknesses between 2.8–3.5 cm for characteristic tissue gamma rays between 2.31 and 6.13 MeV. Therefore an intermediate value of 3 cm was chosen as the optimal detector thickness. This results in optimal dimensions for a ‘practical’ first stage being fixed at 3 cm thick and 10 cm wide.

To maximize the detecting efficiency of the second detector, the three efficiency values dependent on the D2 width and thickness were analyzed, with results shown in figures 2–3. Figure 2 shows the dependence on the D2 width (w2). As with the first detector, the D2 width impacts the number of single scattered gammas from D1 that enter D2. Unlike the D1 transportation efficiency, does not follow the solid angle formula, due to the fact that gammas reaching D2 do not come from a single point, but scatter throughout the entire volume of D1. Figure 2 shows asymptotically approaching a value of approximately 0.85 as w2 increases. Since the D2 transport efficiency continues to increase (albeit slowly beyond 50 cm) over the range of widths studied, a ‘practical’ D2 width of 10 cm was chosen for D3 optimization studies.

Optimizing the D2 thickness requires investigating both the D2 interaction efficiency and the D3 transport efficiency . Figure 3(a) shows both efficiency values as a function of D2 (t2). As with D1, the D2 interaction efficiency (solid triangles) initially increases, reaches a peak value, and then slowly decreases as t2 increases, due to the increasing likelihood of a second gamma interaction occurring within D2 as t2 increases. The product of the two efficiency values is shown in figure 3(b). The combined efficiency values (triangles) produce a maximum efficiency value at t2 values between 2.5 and 3 cm for all three characteristic gamma energies studied, increasing slightly with gamma energy, and thus 3 cm was again chosen as an optimal detector thickness. Therefore, the optimal dimensions for a practical D2 are 3 cm thickness and 10 cm width.

The third detector transport and interaction efficiencies leading to the triple scatter interactions are shown in figures 2–3. Similar to D2, is independent of the D3 thickness (t3), but heavily dependent on the D3 width (w3). Due to the physical width of the previous two detectors, it does not correspond to the solid angle formula but increases only slightly at widths above 50 cm. As with D1 and D2, due to limitations in current manufacturing capabilities with high purity germanium detectors1, a practical width of 10 cm was chosen for D3.

The efficiency value shown in figure 3(a) differs from the interaction efficiencies of D1 and D2. Instead only is affected by t3, and is shown to increase asymptotically toward a maximum value as the D3 thickness increases. This is due to the type of interactions in D3 used to complete the desired ‘triple scatter’ event. These interactions in D3 can be any type of interaction in which position is recorded and the gamma is allowed to interact multiple times within the detector, with only the first interaction being considered. As a result, increasing the D3 thickness causes more useable interactions (pair production, Photo-absorption, Compton scatter) to occur. Due to the asymptotic response of the D3 interaction efficiency as shown in figure 3(a), a value was chosen near the maximum, resulting in a practical t3 value of 10 cm. Finalizing our detector setup, the D3 dimensions that produce an optimized and technically practical Compton camera are 10 cm thick and 10 cm wide. This led to a final ‘practical’ three-stage Compton camera with detector stage dimensions of 3 cm thick–10 cm wide for D1, 3 cm thick–10 cm wide for D2 and 10 cm thick–10 cm wide for D3.

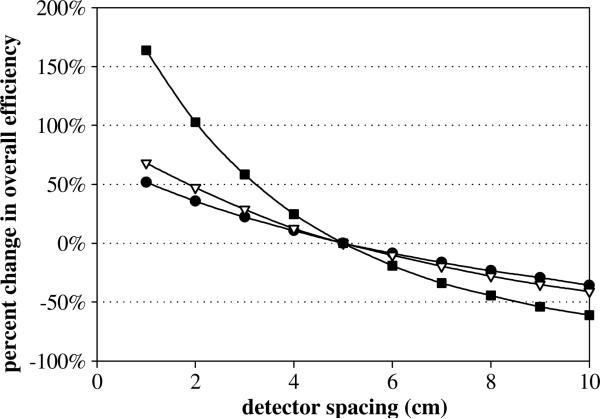

Next, using the optimized and practical camera design, we studied detection efficiency as a function of detector stage spacing by adjusting the detector spacing from the fixed 5 cm inter-detector distance and the 10 cm distance between the phantom and the first detector face. Reducing the inter-detector distance produced an increase in the respective transmission efficiencies resulting in an increase in the overall Compton camera efficiency. For the three scenarios shown in figure 4, the efficiency values obtained with the 5 cm detector gap were used as the comparison point with the largest percent change in efficiency occurring when both detector gaps (D1–D2 and D2–D3) are changed with smaller changes when either the D1–D2 gap or the D2–D3 gaps are held constant. Maintaining the fixed 5 cm inter-detector spacing and modifying the 10 cm distance between the phantom surface and the front face of D1 resulted in a 69% increase in overall efficiency when the distance was reduced to 5 cm and an 83% decrease in overall efficiency for a phantom-detector distance of 40 cm. All detector spacing results were found to be independent of the energy of the prompt gamma rays.

Figure 4.

Percent change in the overall efficiency of the optimized three-stage detector with adjusting the distance between the detectors stages, with three different scenarios. First, varying the gap between D1 and D2 while holding the D2–D3 gap constant (•). Second, holding the D1–D2 gap constant while adjusting the D2–D3 gap (∇). Lastly, changing both the D1–D2 inter-detector gap and the D2–D3 gap (■).

We note that our determination of optimal detection efficiency is dependent on the ability to properly detect and identify useable triple-scatter interactions occurring in the Compton camera. These triple-scatter events occur alongside all other ‘non-usable’ gamma ray interactions occurring in the camera. From our calculations of single-, double- and triple-scatter events, we see that only approximately 0.3% of all gamma rays incident on D1 will result in a usable triple scatter event. These events must then be identified and sorted out from the vast majority of unusable events using a combination of the event timing (Vetter 2007) within each detector stage and Compton kinematics (Kroeger et al 2002). Sorting and identification of the correct scattering sequence of the gamma ray for the triple-scatter event will also be necessary. Improper identification of the gamma scattering sequence in determining a triple-scatter event will lead to increased noise in the resulting image and reduce the detection efficiency of the camera. Techniques for proper sequencing of gamma scattering in the detectors have been extensively studied and several successful techniques based on gamma clustering (Schmid et al 1999, Lee 1999) and neural networking (Schmid et al 1999) algorithms have been demonstrated.

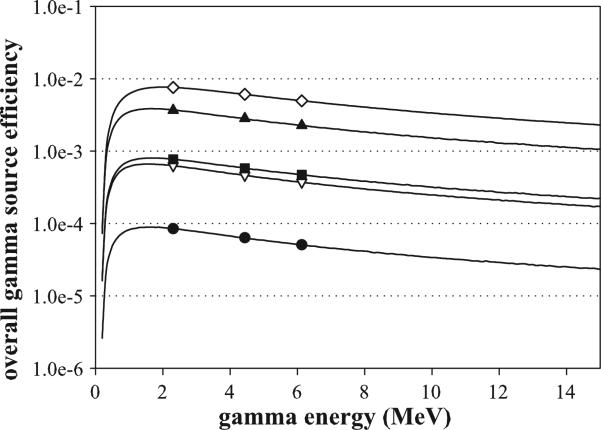

Using the optimized, practical Compton camera dimensions (3 × 10 cm, 3 × 10 cm, 10 × 10 cm), the overall efficiency for the isotropic gamma source was calculated over the range of characteristic prompt gamma rays emitted from tissue as well as for the characteristic prompt gamma peaks from nitrogen, carbon and oxygen (2.31, 4.44 and 6.13 MeV), as shown in figure 5. Although the detector dimensions selected above are considered the optimal dimensions for the three-stage Compton camera, they were chosen with practical design considerations in mind and are not the most efficient possible dimensions. As a result, four additional Compton camera designs (also shown in figure 5) were chosen to demonstrate the impact of increasing the detector widths on the overall gamma source efficiency. The additional configurations are (1) a doubling of the widths of all three stages (3 × 20, 3 × 20, 10 × 20 cm), (2) further increasing the widths to a maximum practical size to fit into a standard proton therapy treatment vault (3 × 50, 3 × 50, 10 × 50 cm), (3) keeping the same first stage design, with an increase of the D2 and D3 widths to 100 cm in order to maximize the D2 and D3 transportation efficiencies (3 × 10, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm), and (4) a very unrealistic setup with 100 cm widths at all three stages (3 × 100, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm). The final two configurations are noted to be not only impractical to manufacture, but also impractical to install within a proton therapy treatment room due to their physical size. We included them in our results solely as a means of evaluating theoretical upper limits of detection efficiency. In each additional detector configuration, the detector stage thicknesses are not changed because our calculations revealed that the optimized thickness for all three stages remained approximately 3 cm for all dimensions studied.

Figure 5.

Overall efficiency results from the isotropic gamma source for energies 0–15 MeV including the characteristic prompt gamma peaks (symbols) of 2.31, 4.44 and 6.13 MeV. Five detector configurations are shown: the practical detector, 3 × 10, 3 × 10, 10 × 10 cm (•), 3 × 20, 3 × 20, 10 × 20 cm (∇); 3 × 50, 3 × 50, 10 × 50 cm (▲); 3 × 10, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm (■); 3 × 100, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm (◇).

Figure 5 also shows that the overall gamma source efficiency exhibits similar characteristics for each of the detector configurations. The increases rapidly for low gamma-ray energies, peaks around 1.8 MeV and then slowly decreases as the gamma energy continues to increase. The sharp increase occurs as the prompt gamma energy increases until it is sufficient to travel through all three stages of the camera without being absorbed. The slow and steady decrease in the efficiency above 2 MeV is a result of the higher energy gammas being more likely to traverse the detector stage without sequentially Compton scattering in both D1 and D2, resulting in lower interaction efficiencies for these two detector stages at higher energies.

Whereas the five configurations exhibit similar characteristics, the magnitude of for each detector setup is considerably different. Figure 5 shows that doubling the detectors lateral dimensions (3 × 20, 3 × 20, 10 × 20 cm) results in an order of magnitude increase in the gamma source efficiency. Interestingly, leaving D1 unchanged, and maximizing the inter-stage transportation efficiencies by expanding the D2 and D3 (3 × 10, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm), produces a similar order of magnitude increase over the practical detector. The maximum practically installable (3 × 50, 3 × 50, 10 × 50 cm) and final ‘theoretical’ maximum (3 × 100, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm) detector configurations provides an additional factor of five and order of magnitude increase in efficiency, respectively, over the previous two configuration. We note here that the larger detector configurations studied (above 10 cm lateral width), since currently impractical for manufacturing as a single Ge crystal, would likely be configured by adding multiple 10 cm × 10 cm detectors together in an array. This would likely result in a linear increase in cost of the detector, due to the addition of more detectors, cooling systems, electronics, etc needed for each 10 × 10 cm detector added to the array. Therefore it can be seen that any increase in detection efficiency achieved through increasing the detector size would also be accompanied by a noticeable increase in cost.

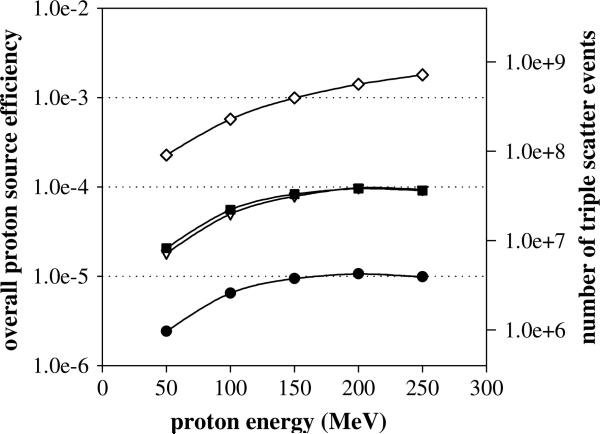

Using four of the Compton camera configurations listed above (all except (3 × 50, 3 × 50, 10 × 50 cm)) with a standard 5 cm spacing, the overall detection efficiency for prompt gammas produced during proton beam irradiation was calculated over a range of energies (50–250 MeV) typically used in proton therapy, shown in figure 6. In comparison to the results for the gamma source efficiency, the difference in magnitude between the four configurations is approximately the same, but the shape of the overall efficiency values changes. The has its lowest value at the lowest proton energy (50 MeV) and steadily increases with energy, although for the three smaller detector configuration (3 × 10, 3 × 10, 10 × 10 cm; 3 × 20, 3 × 20, 10 × 20 cm; 3 × 10, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm), levels off at 200 MeV, whereas the largest detector setup (3 × 100, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm), continues to increase. This can be explained by looking at the characteristics of the prompt gamma production. As the proton energy increases, the total number of prompt gammas produced increases, resulting in an increase in the overall efficiency. The leveling off that occurs at 200 MeV in the three smaller configurations is due to the increased proton beam range in the tissue phantom. In our study, the Compton camera is positioned at the point of maximum prompt gamma production, which occurs near the end of the proton range. However, prompt gamma creation occurs along the whole length of the proton path within the phantom. Since the proton range in tissue at 200 MeV is about 25 cm and the D1 width is only 10 or 20 cm for the smaller configurations, a saturation point is reached where the additional prompt gamma rays created in the phantom along the proton beam path not covered by the camera are not reaching D1. This is seen in figure 6 by the slowing increase in the number of prompt gammas that triple scatter from 150 to 250 MeV. In contrast, the efficiency of the largest detector configuration with a D1 width of 100 cm continues to increase with proton energy because the entire proton range is covered by D1 of the Compton camera for all proton beam energies studied (max proton range in tissue is approximately 35 cm).

Figure 6.

Overall efficiency results (left axis) for detection of prompt gammas produced during proton irradiation from 50 to 250 MeV for the four detector configurations: 3 × 10, 3 × 10, 10 × cm (•); 3 × 20, 3 × 20, 10 × 20 cm (∇); 3 × 10, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm (■); 3 × 100, 3 × 100, 10 × 100 cm (◇). On the right axis is the estimated triple scatter events detected for a typical proton treatment beam delivery of 4 × 1011 protons entering the patient.

Lastly, the overall proton source efficiency results for the optimized detector configuration were used to approximate the number of the triple scatter events detected during a typical proton irradiation. For example, at the University of Texas MD Anderson Proton Therapy Center (PTC-H), a typical daily cancer treatment using the ‘magnetic scanned beam’ system will deliver approximately 1 × 1011 protons per proton beam pulse (Smith et al 2009). Based on the dose rate test discussed in (Smith et al 2009), delivering a standard daily treatment dose of 2 Gy to a 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm volume requires between 5 and 6 beam pulses, resulting in 5–6 × 1011 protons being extracted from the synchrotron for treatment delivery. Using a conservative estimate of 75% for the number of extracted protons that actually reach the patient, the final approximation for a typical treatment is about 4 × 1011 incident protons. Multiplying this value by the overall proton source efficiency gives the results shown on the right hand scale in figure 6. The optimized, practical detector configuration gives 1.0–4.3 106 triple scatter events over the proton energy range studied, with this number increasing by more than 2 orders of magnitude for the largest camera configuration studied, and possibly increasing further still if detector stage spacing is reduced. Using numbers published by Frandes et al (2010), we were able to make a rough determination of whether this is a sufficient number of triple scatter events to reconstruct a useable image. Their work modeled a 140 MeV proton beam with 2.0 × 107 protons hitting a tissue equivalent phantom, from which they were able to reconstruct images of the dose deposition. Although they do not state the exact number of measured gammas used for reconstruction, they estimate 30% of the 140 MeV protons underwent a nuclear scatter event which resulted in the production of a prompt gamma ray, giving about 6.0 × 106 prompt gammas. Based on their geometry, we estimate 1/8 of the gammas hit the ×detector, which, assuming perfect 100% detection efficiency, results in approximately 7.5 × 105 gamma ray detection events to reconstruct their images. Therefore, since this number is approximately a factor of 5 lower than the number of triple scatter events in our practical camera design (with triple-scatter detection increasing for ‘non-practical’ designs), we conclude that the number of prompt gammas measured with the studied optimized camera designs (practical and non-practical) would be sufficient to reconstruct an image.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we investigated an optimized three-stage Compton camera in a parallel, stacked configuration for the purpose of measuring prompt gamma rays emitted from a patient during proton beam radiotherapy. We believe that the results of this study give a good estimation of the effects of lateral size and thickness of the Compton camera stages on the achievable measurement efficiency. We conclude that the dimensions for the optimized and ‘practical’ Compton camera are a 10 cm width for all three germanium detector stages with thicknesses of 3, 3 and 10 cm, for stages 1, 2 and 3, respectively. This optimized configuration was used to evaluate its overall efficiency for measuring prompt gamma rays produced from proton beam irradiations of a tissue phantom with therapeutic proton beam energies. We estimated measurement efficiency values of 2–11 × 10−6 detected ‘triple-scatter’ events per proton entering the tissue phantom. Based on an approximate number of protons entering a patient during a typical proton therapy treatment and the efficiency values calculated in this work, we believe that imaging the prompt gamma rays emitted during proton radiotherapy with a three-stage Compton camera is theoretically feasible.

However, this study only aims to count and optimize the number of triple-scatter events within the camera, thus giving a theoretical estimation of maximum detector efficiency. Overall measurement efficiency with a three-stage Compton camera would be affected by many other factors arising from the physical limitations of a camera. For instance, we note that any measurement would be affected by the actual response time and signal processing limitations of the electronics of an actual Compton camera. Issues such as detector noise, dead time, signal gain, and integration timing will all act to limit achievable count rates of any system and thus limit the achievable detection efficiency of any system. Additionally, limitations in determining exact energy deposition and position of the gamma interaction act to limit the achievable resolution for determining gamma scattering angle (Ordonez et al 2007), which will in-turn limit the imaging resolution of the system. Limitations of the imaging resolution will also act to determine the ultimate clinical feasibility of the proposed Compton camera system. A detailed study of the angular and imaging resolution achievable with the ‘optimized’ three-stage camera detailed in this paper is the focus of ongoing studies at the M D Anderson Cancer Center.

Also, this work focused only on the design of a three-stage Compton camera made with germanium. It is possible that using other detector materials (semiconductors or scintillators) for the various stages could improve the overall efficiency of the camera. Current and future work will be focused on continued design of a Compton camera with the long-term goal of developing a clinically viable online imaging and treatment verification system for proton radiotherapy. This work includes studies of using materials other than germanium in the design of the three-stage camera, as well as construction and testing of a prototype camera and image reconstruction methods.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by award no R21CA137362 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Personal Communication with Ortec, Inc. applications engineers (06/2010).

References

- Agostinelli S, et al. GEANT4—a simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 2003;506:250–303. [Google Scholar]

- Brun R, Rademakers F. ROOT—an object oriented data analysis framework. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1997;389:81–6. [Google Scholar]

- Deleplanque MA, Lee IY, Vetter K, Schmid GJ, Stephens FS, Clark RM, Diamond RM, Fallon P, Macchiavelli AO. GRETA: utilizing new concepts in gamma-ray detection. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1999;430:292–310. [Google Scholar]

- Frandes M, Zoglauer A, Maxim V, Prost R. A tracking Compton-scattering imaging system for hadron therapy monitoring. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2010;57:144–50. [Google Scholar]

- ICRU . Report. Vol. 49. International Commission on Radiation Unis and Measurements; Bethesda, MD: 1993. Stopping power and ranges for protons and alpha particles. [Google Scholar]

- ICRU . Report. Vol. 63. International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements; Bethesda, MD: 2000. Nuclear data for neutron and proton radiotherapy and for radiation protection. [Google Scholar]

- Kang BH, Kim JW. Monte Carlo design study of a gamma detector system to locate distal dose falloff in proton therapy. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2009;56:46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf A, Parodi K, Bortfeld T, Shih HA, Paganetti H. Systematic analysis of biological and physical limitations of proton beam range verification with offline PET/CT scans. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:4477–95. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/14/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger RA, Johnson WN, Kurfess JD, Phlips BF, Wulf EA. Three-Compton telescope: theory, simulations, and performance. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2002;49:1887–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kurfess JD, Johnson WN, Kroeger RA, Phlips BF. Considerations for the next Compton telescope mission. 5th Compton Symp.; Portsmouth, NH, AIP. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lee IY. Gamma-ray tracking detectors. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1999;422:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Min CH, Kim CH, Youn MY, Kim JW. Prompt gamma measurements for locating the dose falloff region in the proton therapy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89:183517. [Google Scholar]

- Nishio T, Sato T, Kitamura H, Murakami K, Ogino T. Distributions of beta(+) decayed nuclei generated in the CH2 and H2O targets by the target nuclear fragment reaction using therapeutic MONO and SOBP proton beam. Med. Phys. 2005;32:1070–82. doi: 10.1118/1.1879692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NNDC 2007 National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory www.nndc.bnl.gov.

- Ordonez CE, Chang W, Bolozdynya A. Angular uncertainties due to geometry and spatial resolution in Compton cameras. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1999;46:1142–7. [Google Scholar]

- Parodi K, Enghardt W, Haberer T. In-beam PET measurements of beta(+) radioactivity induced by proton beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 2002;47:21–36. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/1/302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SW, Polf J, Bues M, Ciangaru G, Archambault L, Beddar S, Smith A. Experimental validation of a Monte Carlo proton therapy nozzle model incorporating magnetically steered protons. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:3217–29. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/10/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polf JC, Peterson S, Ciangaru G, Gillin M, Beddar S. Prompt gamma-ray emission from biological tissues during proton irradiation: a preliminary study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009a;54:731–43. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/3/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polf JC, Peterson S, McCleskey M, Roeder BT, Spiridon A, Beddar S, Trache L. Measurement and calculation of characteristic prompt gamma ray spectra emitted during proton irradiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009b;54:N519–27. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/22/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard MH, et al. Design study of a Compton camera for prompt gamma imaging during ion beam therapy. 2009 IEEE Nuclear Science Symp. Conf. Record; NSS/MIC. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid GJ, et al. A gamma-ray tracking algorithm for the GRETA spectrometer. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 1999;430:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. An electronically collimated gamma-camera for single photon-emission computed-tomography: 1. Theoretical considerations and design criteria. Med. Phys. 1983;10:421–7. doi: 10.1118/1.595313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, et al. The M D Anderson proton therapy system. Med. Phys. 2009;36:4068–83. doi: 10.1118/1.3187229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styczynski J, Riley K, Binns P, Bortfeld T, Paganetti H. SU-DD-A3-03: can prompt gamma emission during proton therapy provide in situ range verification? Med. Phys. 2009;36:2425. [Google Scholar]

- Takada A, et al. Development of an advanced Compton camera with gaseous TPC and scintillator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 2005;546:258–62. [Google Scholar]

- Testa E, et al. Monitoring the Bragg peak location of 73 MeV/u carbon ions by means of prompt gamma-ray measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;93:093506. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter K. Recent developments in the fabrication and operation of germanium detectors. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2007;57:363–404. [Google Scholar]

- Vynckier S, Derreumaux S, Richard F, Bol A, Michel C, Wambersie A. Is it possible to verify directly a proton-treatment plan using positron emission tomography. Radiother. Oncol. 1993;26:275–7. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]