Abstract

The influence of parenting skills on adolescent outcomes among children affected by maternal HIV/AIDS (N = 118, M age = 13) was investigated. Among families with more frequent family routines, over time adolescents showed lower rates of aggression, anxiety, worry, depression, conduct disorder, binge drinking, and increased self-concept. Among families with higher levels of parental monitoring, adolescents showed significant declines in anxiety and depression, conduct disorder, and binge drinking, along with increased self-concept. Mothers’ level of illness was associated with parenting. Greater variability in parental monitoring resulted in higher levels of problem behaviors.

HIV/AIDS and cancer research indicates that parental illness status and mental health have been found to affect parenting behaviors. Illness severity is associated with higher levels of psychological distress in chronically ill adults (e.g., Derogatis et al., 1983; Rodin & Voshart, 1986; Woods, Haberman, & Packard, 1993) and to some extent in their children (e.g., Armistead, Klein, & Forehand, 1995; Worsham, Compas, & Ey, 1997). Among families with a parent with AIDS, as illness progresses parents are likely to exhibit maladaptive behaviors that disrupt the parent-child relationship (Cates, Graham, Boeglin, & Tiekler, 1990; Lamping et al., 1991). Dorsey et al. (1999) found a linear increase in child report of externalizing and internalizing difficulties through their mother's infected symptomatic stage and through her AIDS stage.

Being raised in a family where a parent has mental health problems, particularly depression, can result in detrimental cognitive, social-emotional, and behavioral outcomes in the children (Elgar, Curtis, McGrath, Waschbusch, & Stewart, 2003; Johnson & Flake, 2007; Luthar & Sexton, 2007). Depressed parents typically have restricted response repertoires that may disrupt family routines, and may be limited in their interactions with family members--especially their children (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1988). Research has found that HIV-infected mothers as well as their children report higher levels of depressive symptoms than non-infected mothers and their children (Biggar & Forehand, 1998; Forehand et al., 2002).

A large number of studies have been conducted to identify and describe the conditions associated with poor outcomes of early and middle age adolescents as well as protective factors (e.g., Loukas & Prelow, 2004). The term protective throughout the studies described in this overview include both main effect findings and interaction effects, which have been distinguished in other cases per Cicchetti & Cohen, 2006. Some recent studies have examined family factors and outcomes among young children affected by maternal HIV (e.g., Forehand et al., 2002, Jones et al., 2008). However, to our knowledge, no studies have focused on family factors and outcomes in early/middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS, other than a limited number of studies as noted above on HIV infected mothers and children reporting higher levels of depression. Family variables—especially parenting skills—may protect these children from risk. Parenting skills such as implementing and maintaining family routines and parental monitoring have been found in some studies to be protective factors for early and middle adolescents in some adverse circumstances for some domains of functioning (e.g., Beyers, Bates, Pettit, & Dodge, 2003; Hair, Moore, Garrett, Ling, & Cleveland, 2008; see also Fiese et al, 2002).

The various factors that function to positively influence youth outcomes have been summarized by Wyman, Sandler, Wolchik, and Nelson (2000; see also Wyman et al., 1999) in their organizational-developmental framework of resilience. Resilience is viewed “as a child's achievement of positive developmental outcomes and avoidance of maladaptive outcomes, under significantly adverse conditions” (Wyman et al., 2000). In other words, given negative social/environmental conditions (e.g., poverty, parental health constraints), youth considered resilient are those adapting and functioning well despite adverse circumstances in certain domains, without succumbing to negative influences that can lead to maladaptive coping and behaviors. The protective factors identified by Wyman et al. include individual, family, and community factors, which can positively influence the adaptation process of youth in negative social/environmental conditions, enhancing cognitive-affective well being and related outcomes. Research on the effects of family routines and parental monitoring (e.g., Beyers et al., 2003; Hair et al., 2008), as family factors, may be viewed within this framework (also see below), with routines and monitoring leading to positive outcomes. For the current study, it is expected that the active presence of family routines and parental monitoring will lead to more positive outcomes regarding adolescent psychological well being and related behaviors.

Family Routines

Implementation and maintenance of family routines is a critical parenting skill. Routines have been defined as activities that occur in the “same order and at about the same time each day” (Cassidy, 1992) and conceptualized as typically involving instrumental communication conveying information that “this is what needs to be done,” (Fiese et al., 2002). Family routines also have been defined as “the predictable, repetitive patterning which characterizes day-to-day, week-to-week existence within a given nuclear family unit, the shared pattern of behavioral rhythmicity that serves an ordering principle in the ongoing process of a family's existence” (Boyce, Jensen, James, & Peacock, 1983, pp. 194). Thus, routines are patterned interactions that are repeated over time and recognized by continuity in behavior (Fiese et al., 2002; Wolin & Bennett, 1984), and are observable and occur with predictable regularity (Boyce et al., 1983). Family routines are considered to be indicative of family organization and to be important for a family's psychological health and well being (Reiss, 1989; Steinglass, Bennett, Wolin, & Reiss, 1987). Particularly for early/middle adolescents the “rhythmicity that serves an ordering principle” part of family routines may be especially critical for a sense of stability. Despite the fact that the importance of establishing predictable routines during childhood has consistently been emphasized in popular parenting literature, family routines have been the focus of very little systematic empirical study (Boyce et al.; Sytsma, Kelley, & Wymer, 2001).

Routines are reported to be critical in the establishment of children's sense of predictability and feelings of security (e.g., Cassidy, 1992; Hall, 1997; Kase, 1999). In a review of 50 years of research on family routines and rituals, Fiese et al. (2002) reported that family routines are related to parenting competence and child adjustment. For example, among a sample of poor African-American mothers and their 6 to 9-year old children, families with routinized environments were directly associated with better academic achievement and fewer internalizing problems among males, while among females they were indirectly associated with externalizing and internalizing problems (Brody & Flor, 1997).

As noted, few studies have been conducted investigating the impact of family routines on adolescent outcomes. Stephenson, Henry, and Robinson (1996) suggested regularity in family time and routines, with an emphasis on routine consistency, is a protective factor against adolescent substance use, including alcohol use (Stephenson et al. did not use a measure that distinguished between substances); however, results were inconclusive. In univariate analyses family routines were negatively related to teen substance use but this was not supported in multiple regression analysis, where the only significant family characteristics were coherence and hardiness. Specifically, the family characteristics that related to regularity and tradition in interaction patterns such as observance of celebrations and events (e.g., birthdays, religious occasions, and holidays) were not found to be significantly related to adolescent substance use in the overall models. Additionally, the observance of family time and routines were not significant in the overall models. Among 10 – 14 year old Latino adolescents, Loukas and Prelow (2004) found that maintenance of family routines protected females exposed to elevated levels of cumulative risk from heightened levels of externalizing problems. One study utilizing the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth data reported that the relationship between parents and their adolescent children relates to adolescent development primarily through the association with subsequent routine family activities, and perceived parental awareness and supportiveness (Hair et al., 2008). Finally, in a sample of over 4,000 families with 11 - 18 year old middle and high school students from ethnically and socioeconomically diverse communities, family routines—particularly routines related to family meals—has been shown to be negatively related to alcohol use; low grade point average; depressive symptoms; and suicide involvement after controlling for family connectedness (Eisenberg, Olson, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Bearinger, 2004). In that study, for example, as the number of family meals eaten together declined, the likelihood of the adolescents having used alcohol in the past year increased. The authors concluded that family mealtime was a potentially protective factor in the lives of adolescents, and controlling for family connectedness.

Parental Monitoring

Parental monitoring is typically defined as a parent's knowledge of their child's whereabouts, activities, and friends (Jacobson & Crockett, 2000). Parental monitoring is considered an essential parenting skill (Jones, Forehand, Brody, & Armistead, 2003), and to be especially critical during early and middle adolescence. Numerous studies have linked higher levels of parental monitoring to lower levels of adolescent antisocial behavior and alcohol use (e.g., Guo, Hawkins, Hill, & Abbott, 2001; Hayes, Smart, Toumbourou, & Sanson, 2004; Snyder, Dishion, & Patterson, 1986; Steinberg, Fletcher, & Darling, 1994). Additionally, parental monitoring has been linked to adolescents’ school functioning (Brown, Mounts, Lamborn, & Steinberg, 1993; Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992). Degree of adolescent self-reliance also has been predicted by parental monitoring (Linver & Silverberg, 1995).

Finally, there is some research that indicates parental monitoring may be associated with adolescents’ psychological well being, but these findings are not as strong as those linking parental monitoring with delinquency, or school performance. For example, one study found that lack of behavioral control by parents (which included an assessment of parental monitoring) was related to adolescent internalizing problems, and more strongly related to adolescent externalizing problems (Barber, Olsen, & Shagle, 1994). However, Linver and Silverberg (1995) reported that parental monitoring did not account for any additional variance for self-esteem or psychological symptoms, after respect of the adolescent by the parent or parent psychological control was entered into hierarchical regression.

Some of the discrepant findings for parental monitoring may have to do with individual characteristics of the children within these families. For example, age may play a factor in the impact of parental monitoring. Among African-American children age 9 – 17, perceived parental monitoring tended to decrease with advancing age of the youth (Li, Feigelman, & Stanton, 2000). Other studies indicate that perceived parental control may become increasingly important as adolescents age and enter high school (Foxcraft, 1994).

Summary and Purpose of the Present Study

Parental skills, such as the implementation and maintenance of family routines and parental monitoring, are especially critical during early and middle adolescence. Moreover, it has been suggested that such parenting skills may play an especially important role in families with a chronically ill member (e.g., Greene Bush, & Pargament, 1977). Maternal HIV may disrupt effective parenting. For example, HIV-infected mothers report less monitoring of children's activities than do non-infected mothers (Kotchick et al., 1997). Among families with HIV-infected mothers, parental monitoring has been associated with child resiliency (Dutra et al., 2000). Specifically, Dutra et al. found that high levels of structure in the home in the presence of high levels of parental monitoring and high levels of a positive mother-child relationship in the presence of high levels of parental monitoring were associated with increased likelihood of child resiliency. While there has been a great deal of research on parental monitoring and child outcomes in the general family literature, there is very little research on the impact of parental illness on child outcomes, or on the impact of parental illness on parenting skills. In fact, research on the impact of parental illness on children is sparse (Mukherjee, Sloper, & Lewin, 2002): beginning in 1959 (Arnaud) and since then for the past 45 years, researchers have consistently commented on a lack of systematic study on the influence chronic parental illness has on child development (Armistead et al., 1995; Brandt & Weinert, 1998; Buck & Hohmann, 1983; Champion & Roberts, 2001; Grue & Lærum, 2002; Peters & Esses, 1985; Smith & Soliday, 2001; Stuifbergen, 1990). Armistead, Klein, and Forehand (1995) have conducted a review of the few studies that examine the relationship between parental illness and child functioning, and tentatively concluded that an association does exist, although findings are somewhat disparate. While that review was conducted more than a decade ago, there has been slow progress in this area since their report. Smith and Soliday (2001) interviewed parents with chronic kidney disease and found that chronic illness effects parents’ perceived role functioning, which in turn influences their perceived family functioning. However, the fact that approximately 50% of the potential participants did not respond limits the generalizability of that study. There has been even less research conducted that investigates the effect of parental illness on the parent's own parenting skills.

The present study was an attempt to focus on early and middle age adolescent children affected by maternal HIV, with an emphasis on investigating parenting skills (i.e., family routines and parental monitoring) and early/middle adolescent outcomes within an organizational-developmental framework of resilience. Specifically, we hypothesized that: (1) higher levels of both family routines and parental monitoring will have a positive effect on child/adolescent outcomes in families affected by maternal HIV/AIDS (i.e., mental health indicators, self-concept, and behavioral problems); (2) maternal risk factors for poor child/adolescent outcomes (i.e., maternal physical and mental health) will negatively influence their implementation of parental skills (i.e., family routines and parental monitoring); and (3) the stability of these parental skills over time will be associated with improved adolescent outcomes, with greater stability yielding improved outcomes.

Method

Participants

The Parents and Adolescents Coping Together study (PACT II) is a continuation of a longitudinal assessment study of 135 mothers with HIV/AIDS and their well children age 6 – 11 conducted from 1997 to 2002 (Parents and Children Coping Together). The PACT II study continued to follow 81 of the original families in the PACT study as the children transitioned to early and middle adolescence, and the original sample was supplemented with 37 new families, for a total of 118 families. Comparison of the 37 new families with the 81 original families indicates that at baseline there were no significant differences in the mothers’ marital status, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, or child gender. Mothers who did not participate in PACT I were somewhat younger than the those who were in PACT I, with a mean age of 37.4 (SD = 5.2) vs. 40.0 (SD = 6.0); t (116) = -2.23, p < .001. Similarly, children who were not in PACT I were somewhat younger, with a mean age of 12.0 (SD = 1.0) vs. 13.4 (SD = 1.9); t (116) = -4.22, p < .001. (The child age inclusion for new families was having a child age 11 - 14, whereas the children in PACT I ranged from age 10 - 17 at the PACT II baseline interview.)

Inclusion criteria were: confirmation of either AIDS diagnosis or HIV-symptomatic status of the mother, having a well child age 11–14½, and English or Spanish speaking. All PACT II study participants providing data for the present analysis were recruited from clinical primary care sites and AIDS service organizations in Los Angeles County, and had a baseline interview conducted between June 2003 and October 2004. A total of six time-points in the study are included in this analysis: baseline, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30-month follow-up. Medical chart abstraction was conducted to verify eligibility. If a mother had more than one eligible well child in the targeted age range, the child with the most recent birthday was selected for participation.

Measures

Adolescent Assessment

Depression

The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985; Kovacs & Beck, 1977) was administered to the adolescents. The CDI is a widely used, reliable self-report measure of childhood distress and depressive symptomatology (Curry & Craighead, 1993). The scale consists of five subscales: Negative Mood, Interpersonal Problems, Ineffectiveness, Anhedonia, and Negative Self-Esteem. For the current sample, total score internal consistency was .91.

Anxiety

The worry/oversensitivity subscale and physiological anxiety subscales from the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) were administered to the adolescents. (Only two subscales were administered to keep subject burden reasonable.) The RCMAS is a commonly used measure of anxiety in children and adolescents; content, construct, concurrent, and predictive validity have been previously demonstrated in a national sample of 6 to 19 year olds (Reynolds & Richmond, 1978; 1985). Cronbach's alpha for this sample was .83 for the oversensitivity scale, and .70 for the physiological anxiety scale.

Self concept

The Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale was administered to the adolescents. The Piers-Harris scale is a widely employed self-concept measure designed for use with adolescents and preadolescents, and has been recommended as a psychometrically sound instrument (Hughes, 1984; Piers, 1993). The four subscales used in this analysis were the intellectual and school status scale; the popularity scale; the happiness and satisfaction scale; and the physical appearance and attributes scale. Cronbach's alpha for each subscale in this sample was: 74, .72, .67; and .85, respectively. Note that the alpha for the happiness and satisfaction scale might be considered low (.67); additional information on the viability of this measure, including correlations of the measure with other study measures, and correlations corrected for attenuation (see Schmitt, 1996) are available upon request from the authors.

Conduct disorder and aggressive behavior

Twenty-four conduct disorder items currently used in the NICHD Adolescent Trials Network survey of high-risk youth were administered to adolescents at each time point to determine involvement in delinquent acts (e.g., “Have you ever shoplifted?”; “Have you ever run away from home overnight?”). The alpha coefficient for this sample was .87.

In addition, the aggressive behavior scale from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1978; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1979) was administered to the mother, to assess behavioral/emotional problems in the adolescent. The CBCL has standardized competence items that discriminate significantly between children adapting successfully and children with behavioral or emotional problems. Cronbach's alpha for this sample was .91.

Alcohol use

Items used in the NICHD Adolescent Trial Network's survey of high-risk youth were used to assess alcohol and drug use among adolescents. The adolescents were first screened to determine if they had ever had drinks containing alcohol (i.e., more than a couple of sips). For those who responded affirmatively, follow up questions included items pertaining to frequency and intensity of use. The present analysis examined heavy alcohol use, defined as having five or more drinks per day on a typical day when the youth was drinking. Scale responses included “Never”, “Less than monthly”, “Monthly”, “Weekly”, and “Daily or almost daily.”

Family routines

A subset of 8 questions from The Family Routines Questionnaire was administered to the adolescents at each of the study time points. This inventory included such items as, “In our family, children go to bed at the same time each night”, and, “In our family, the whole family eats dinner together.” The items were scored on a 4-point scale with higher scores equaling more frequent involvement in each family routine (4 = everyday; 3 = 3 - 5 times per week; 2 = 1 - 2 times per week; 1 = almost never). The Cronbach's alpha for the sample of adolescents was .82.

Parental monitoring

Selected items from the parental monitoring scale (Steinberg et al., 1992; 1994) were administered to the adolescents at each of the study time points. Eleven items assess the extent to which the adolescent's mother knows about the adolescent's whereabouts, activities, who his/her friends are, and related questions. Responses range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher parental monitoring. The 11 questions were summed then divided by the total number of answered questions. The Cronbach's alpha in this sample was .86.

Maternal Assessment

Maternal health status and illness

The Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36 (MOS SF-36; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) was administered to the mothers at each time point. This brief but comprehensive and psychometrically sound questionnaire includes sub-scales that measure physical functioning, impairment related to health and to psychological problems, pain, energy and fatigue, and general health perceptions. The MOS SF-36 has been found to be responsive to clinical change over time (for a brief review, see Ware, Gandek, and the IQOLA Project Group, 1994).

The physical functioning, vitality and bodily pain subscales were chosen for this study because they provide both the mother's report of her activity limitations (which may be more easily observable by the child) and how she was feeling physically. The physical functioning scale measures the extent to which one's current health limits typical daily activities such as walking, climbing stairs carrying groceries, bending, kneeling, and stooping. The vitality scale assesses one's energy level and fatigue, and the bodily pain scale assesses one's level of pain and extent to which pain interferes with daily activities. Higher scores indicate better functioning. Alpha coefficients for the subscales were as follows: physical functioning .91; bodily pain .83; and vitality .79.

Maternal physical health was also assessed using the mother's report of the number of HIV illness symptoms she was experiencing (e.g., unexpected weight loss, skin sores, shortness of breath) in the past six months.

Maternal depression

The Hamilton Depression Inventory (HDI; Reynolds & Kobak, 1995) is a 23-item measure of the severity of adult depressive symptomatology, and was administered to the mothers at each time point. Cronbach's alpha for this sample was .87.

Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board. Clinic staff at recruitment sites reviewed patient files, identified eligible families, and obtained verbal consent for UCLA interviewers to contact potential participants. In addition, flyers and brochures for the project were available, and patients could contact study staff directly. A total of 214 potential participants were identified for this study, of whom 24% were determined to be ineligible based on criteria noted above; 13% declined to participate, and 87% of eligible potential participants (N = 118) were enrolled in the study. After receiving a complete description of the study, mothers who agreed to participate signed the IRB-approved Informed Consent and adolescents signed the assent form; adolescents 18 and over signed a consent form. Trained bilingual interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews in the family's home or at the recruitment site, depending on the preference of the family. Interviews of mothers and adolescents were conducted simultaneously in separate rooms using a computer-assisted interviewing program (CAPI) on laptop computers. Mothers were paid $35 for their participation, and adolescents were paid $25 for their participation. Study participants and procedures are described in further detail in Murphy, Austin, & Greenwell (2006).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the predictor and outcome measures (observed means, standard deviations) are noted in Table 1. Individual growth models were utilized for the longitudinal analysis. Age of the child (mothers’ report), family routines, and parental monitoring were used as fixed effects covariates to predict the outcome variables. All covariates are “time-varying” meaning they were measured across each point in time along with the outcomes unless otherwise noted (e.g., see “stability” analysis in the Results), and were mean-centered except for age. Age was scale-centered by taking the lowest age value (10 years) and subtracting that from individuals’ age (Singer & Willett, 2003) to provide more interpretable results. Statistical tests were evaluated using a .05 level of significance. Only fixed effects of the covariates are reported since they are the effects of interest. SAS Proc Mixed was used for all analyses with restricted maximum likelihood.

Table 1.

Observed Means, Standard Deviations, and N for Select Analysis Variables Across Time

| Baseline M (SD, N) | 6-Month FU M (SD, N) | 12-Month FU M (SD, N) | 18-Month FU M (SD, N) | 24-Month FU M (SD, N) | 30-Month FU M (SD, N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Behavior Checklist | ||||||

| Aggressive Behavior | 10.55 (7.85, 118) | 10.47 (7.64, 112) | 10.35 (7.46, 108) | 9.94 (7.55, 97) | 9.88 (7.25, 97) | 9.21 (6.21, 89) |

| RCMAS | ||||||

| Physical Anxiety | 2.34 (2.18, 118) | 1.96 (2.09, 111) | 2.24 (2.29, 110) | 1.93 (2.00, 102) | 2.30 (2.45, 99) | 2.32 (2.62, 93) |

| Worry/Oversensitivity | 3.57 (3.06, 117) | 3.13 (2.79, 111) | 2.83 (2.83, 109) | 2.78 (2.81, 101) | 2.57 (2.55, 99) | 2.94 (2.90, 93) |

| Child Depression Inventory | ||||||

| Total | 6.28 (4.96, 117) | 6.39 (5.67, 111) | 5.50 (5.02, 110) | 5.84 (5.97, 102) | 5.90 (5.95, 99) | 5.29 (5.56, 91) |

| Negative Mood | 1.37 (1.44, 118) | 1.23 (1.55, 111) | 1.00 (1.31, 110) | 1.23 (1.75, 102) | 1.21 (1.64, 99) | 0.97 (1.49, 92) |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.76 (1.11, 118) | 0.71 (1.02, 112) | 0.53 (1.03, 102) | 0.54 (1.03, 102) | 0.53 (0.94, 99) | 0.68 (1.12, 92) |

| Ineffectiveness | 1.40 (1.51, 118) | 1.68 (1.72, 112) | 1.41 (1.50, 110) | 1.55 (1.79, 102) | 1.45 (1.53, 99) | 1.32 (1.56, 92) |

| Anhedonia | 2.25 (2.14, 118) | 2.17 (2.18, 112) | 2.03 (2.01, 110) | 1.92 (2.13, 102) | 2.13 (2.51, 99) | 2.07 (2.32, 91) |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 0.59 (0.90, 117) | 0.61 (0.94, 112) | 0.54 (0.94, 110) | 0.61 (1.09, 102) | 0.58 (1.03, 99) | 0.29 (0.79, 92) |

| Conduct | 2.94 (3.80, 118) | 2.89 (3.51, 112) | 2.95 (3.63, 110) | 3.27 (3.83, 102) | 3.92 (4.14, 99) | 3.98 (4.35, 93) |

| Piers-Harris | ||||||

| Intellectual and School Status | 13.42 (2.66, 118) | 12.12 (3.11, 112) | 13.29 (2.90, 109) | 13.57 (2.63, 100) | 13.47 (2.89, 96) | 13.42 (3.11, 90) |

| Popularity | 9.88 (2.19, 115) | 9.92 (2.17, 111) | 10.00 (2.02, 108) | 10.25 (2.12, 101) | 10.24 (1.94, 97) | 10.11 (1.90, 90) |

| Happiness and Satisfaction | 9.19 (1.40, 116) | 9.17 (1.45, 111) | 9.37 (1.22, 108) | 9.39 (1.05, 102) | 9.32 (1.24, 99) | 9.37 (1.32, 92) |

| Physical Appearance and Attributes | 10.35 (3.10, 112) | 10.83 (2.56, 111) | 10.97 (2.58, 109) | 11.21 (2.30, 100) | 11.42 (2.40, 96) | 11.53 (2.32, 89) |

| Had 5+ Alcohol Drinks in one day | 0.37 (0.85, 118) | 0.43 (0.87, 112) | 0.52 (0.95, 110) | 0.61 (1.05, 102) | 0.69 (1.00, 99) | 0.77 (1.09, 93) |

| Family Routines | 21.33 (6.14, 117) | 20.97 (6.08, 112) | 21.21 (6.05, 110) | 20.43 (5.88, 102) | 19.80 (5.65, 98) | 18.90 (5.78, 92) |

| Parental Monitoring | 4.28 (0.73, 118) | 4.37 (0.68, 112) | 4.35 (0.71, 110) | 4.34 (0.67, 102) | 4.34 (0.68, 99) | 4.27 (0.81, 93) |

Unconditional growth models are first presented, with age as the only fixed effect covariate with random intercepts and slopes. Next, conditional growth models are presented which build on the unconditional growth models by adding family routines, followed by parental monitoring as fixed effect covariates. Interaction terms (age by family routines) were also assessed in these models to evaluate whether the covariates’ effects on the outcome variables varied across age. Evaluating first family routines, followed by the addition of parental monitoring and subsequent interaction effects between age by family routines, was preferred due to the strong prior research of family routines on adolescent outcomes.

Results

Fifty-two percent of the adolescents in the study were male, and the mean age at baseline was 13 years (SD = 1.8; age range = 10–17). The mean age for mothers at baseline was 39 years (SD = 5.8; range = 28 - 57). The mothers’ race/ethnicity was as follows: 60% Latina; 28% African American; 5% White (non-Latina); 4% multiracial; 2% Asian American; and 1% American Indian. No race/ethnicity differences (using Latina, African American, White, and Multiracial/Other) were found at baseline on family routines and parental monitoring as a multivariate composite using MANOVA (Pillai's Trace = .04, F[6, 226] = .80, p = .57), nor were differences noted across the six time-points on race/ethnicity for family routines using repeated measures MANOVA (Pillai's Trace = .19, F[15, 237] = 1.09, p = .36), or on parental monitoring (Pillai's Trace = .14, F[15, 243] = .81, p = .66). Half of the mothers (50%) had not completed high school; 21% had completed high school or received their GED; and 29% had some education beyond high school. About three-fourths (77%) had not worked in the last month; 77% were not currently married. Most of the mothers were prescribed highly active antiretroviral therapy (78%). Based on medical chart abstractions (including viral load and CD4 counts; viral load refers to the amount of the virus in the blood [lower viral loads indicate better health], and higher CD4 counts [i.e., T-cells] indicate better health.), the median viral load (RNA copies per ml) at baseline was 400; 57% had a viral load of 400 or less; 22% had a viral load of 401-10,000; 12% had a viral load of 10,001 - 50,000; and 9% had a viral load over 50,000. Regarding CD4 counts at baseline, medical chart reviews showed 40% of the mothers had counts of 500 or above; 38% had counts between 499-200; and 22% had counts below 200.

Unconditional Growth Models

Results from the unconditional growth models including only the predictor “age” are noted in Table 2. All intercepts (representing the average individuals’ score in the study) were significantly different from zero. Significant negative slopes for age were noted for the CBCL aggressive behavior scale, RCMAS worry/oversensitivity subscale, CDI total score, and CDI subscales Negative Mood, Interpersonal Problems and Negative Self-esteem. This indicates that as individuals age, there were declines in these measures. Significant positive slopes were noted for conduct disorder behaviors, the Piers-Harris physical appearance and attributes subscale, and heavy drinking (defined as having five or more alcohol drinks in a day). This indicates that as individuals’ age, they report increases in delinquent acts, self-perception of physical appearance and attributes, and heavy drinking.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates, Standard Errors, and Significance Tests for Unconditional Growth (Age), and Conditional Growth Models With Family Routines as a Covariate

| Unconditional Model |

Conditional Model with Family Routines |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Intercept (SE) | Slope of Age (SE) | Intercept (SE) | Slope of Age (SE) | Slope of Routines (SE) |

| Child Behavior Checklist | |||||

| Aggressive Behavior | 12.61*** (1.10) | -0.6** (0.20) | 12.72*** (1.08) | -0.63** (.19) | -0.11* (0.04) |

| RCMAS | |||||

| Physical Anxiety | 2.39*** (0.30) | -0.05 (0.07) | 2.65*** (0.30) | -0.12 (0.07) | -0.05*** (0.01) |

| Worry/Oversensitivity | 3.89*** (0.42) | -0.24* (0.09) | 4.08*** (0.41) | -0.29** (0.09) | -0.04* (0.02) |

| Child Depression Inventory | |||||

| Total | 7.18*** (0.75) | -0.33* (0.16) | 8.00*** (0.71) | -0.53*** (0.15) | -0.24*** (0.04) |

| Negative Mood | 1.53*** (0.19) | -0.09* (0.04) | 1.69*** (0.19) | -0.13*** (0.04) | -0.05*** (.01) |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.88*** (0.13) | -0.06* (0.02) | 0.99*** (0.13) | -0.09*** (0.02) | -0.04*** (0.01) |

| Ineffectiveness | 1.55*** (0.21) | -0.02 (0.05) | 1.72*** (0.21) | -0.06 (0.04) | -0.05*** (0.01) |

| Anhedonia | 2.30*** (0.29) | -0.06 (0.07) | 2.61*** (0.27) | -0.14* (0.06) | -0.08*** (0.2) |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 0.83** (0.13) | -0.07** (0.03) | 0.90*** (0.12) | -0.09*** (0.02) | -0.03*** (0.01) |

| Conduct | 1.23* (0.47) | 0.55*** (0.12) | 1.58** (0.48) | 0.46*** (0.12) | -0.06** (0.02) |

| Piers-Harris | |||||

| Intellectual and School Status | 13.00*** (0.39) | 0.09 (0.07) | 12.58*** (0.37) | 0.19* (0.07) | 0.13*** (0.02) |

| Popularity | 9.63*** (0.33) | 0.10 (0.06) | 9.51*** (0.33) | 0.14* (0.07) | 0.03* (0.01) |

| Happiness and Satisfaction | 9.02*** (0.21) | 0.07 (0.04) | 8.90*** (0.20) | 0.10* (0.04) | 0.05*** (0.01) |

| Physical Appearance and Attributes | 9.52*** (0.43) | 0.38*** (0.08) | 9.26*** (0.43) | 0.44*** (0.09) | 0.08*** (0.02) |

| Had 5+ Alcohol Drinks in One Day | -0.15* (0.06) | 0.16*** (0.03) | -0.05 (0.06) | 0.13*** (0.03) | -0.02*** (0.01) |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Conditional Growth Models

Family Routines as Covariate

The child report of family routines was added to the model as a fixed effect to form a conditional growth model (see Table 2 for findings). As with the unconditional models, all intercepts were significantly different from zero except heavy drinking, and slopes for age were comparable.

Results for family routines show significant negative slopes for the CBCL aggressiveness subscale, both RCMAS subscales of physiological anxiety and worry/oversensitivity, the CDI scale overall, all of the CDI subscales, conduct disorder behaviors, and heavy drinking. This indicates that as family routines increase, there are significant declines in aggressive behavior, anxiety and worry, general and specific forms of depression, conduct disorder behaviors, and heavy drinking. Positive slopes were noted for the four Piers-Harris self-concept subscales, indicating increases in these measures as family routines increase.

To verify the constancy of the family routines findings, the conditional models were also assessed after adjustment for a number of covariates, including family structure variables similar to those noted in Dutra et al. (2000) and demographics. The additional variables consist of a time-invariant covariates (child's gender, mother's race/ethnicity dummy coded to indicate African-American race/ethnicity, whether other children are in the household [present/not present]), and time-varying covariates (mother's marital status [married/unmarried], household income). With these covariates in the models, all but one of the family routines findings (RCMAS worry/oversensitivity, p = .06) were retained.

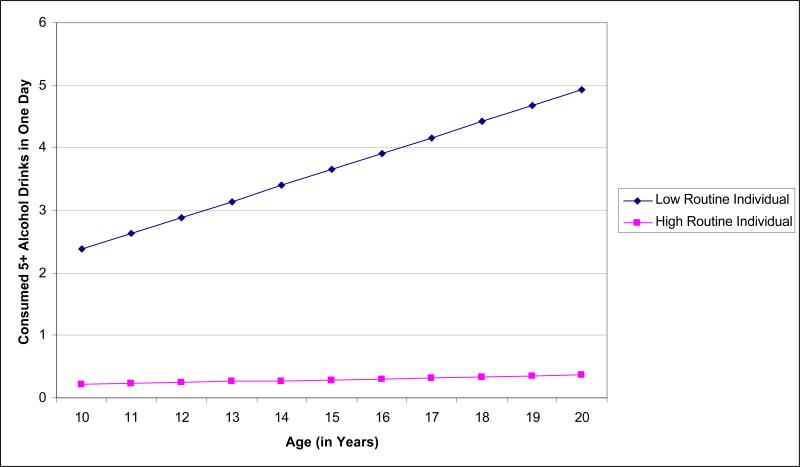

Overall, the addition of family routines to the unconditional model led to more pronounced slopes across most of the outcome variables. An interaction between family routines and age was investigated to evaluate whether the covariates’ effects on the outcome variables varied across age. These effects were generally nonsignificant except for a significant interaction between family routines and heavy drinking. Interpretation of this interaction was performed by generating estimated trajectories using the resulting growth curve model fixed effect coefficients, and plotting low and high values for routines across age on this outcome. Figure 1 presents the estimated trajectories for cases low and high in reported family routines on heavy drinking (low and high values based on reported values from study participants). Per Figure 1, the trajectory for those reporting fewer family routines show distinct increases in heavy drinking as individuals get older.

Figure 1.

Projected trajectories for individuals reporting low and high family routines on consuming five or more alcohol drinks in one-day by age

Note: Growth curve model estimates used for trajectories: intercept (-0.05), age slope (0.13), family routines slope (0.01), and interaction of age and family routines (-0.01)

Family Routines and Parental Monitoring as Covariates

Parental monitoring was next added to the model as a fixed effect (see Table 3). Therefore, the set of models investigated built upon the unconditional model with the inclusion of family routines and parental monitoring as fixed effects. All intercepts were significantly different from zero except for heavy drinking, and slopes for age and family routines were similar to those previously reported for the previous conditional models.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates, Standard Errors, and Significance Tests for Conditional Growth Models with Family Routines and Parental Monitoring as Covariates

| Intercept (SE) | Slope of Age (SE) | Slope of Routines (SE) | Slope of Monitoring (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Behavior Checklist | ||||

| Aggressive Behavior | 12.71*** (1.08) | -0.63** (0.19) | -0.10* (0.05) | -0.23 (0.39) |

| RCMAS | ||||

| Physical Anxiety | 2.65*** (0.29) | -0.12 (0.07) | -0.04* (0.02) | -0.37** (0.13) |

| Worry/Oversensitivity | 4.08*** (0.41) | -0.29** (0.09) | -0.03 (0.02) | -0.14 (0.17) |

| Child Depression Inventory | ||||

| Total | 8.13*** (0.70) | -0.56*** (0.15) | -0.16*** (0.04) | -2.05*** (0.34) |

| Negative Mood | 1.76*** (0.19) | -0.14*** (0.04) | -0.03* (0.01) | -0.36*** (0.10) |

| Interpersonal Problems | 1.05*** (0.12) | -0.10*** (0.02) | -0.02* (0.01) | -0.48*** (0.07) |

| Ineffectiveness | 1.76*** (0.21) | -0.07 (0.04) | -0.04** (0.01) | -0.41*** (0.11) |

| Anhedonia | 2.65*** (0.26) | -0.15* (0.06) | -0.06*** (0.02) | -0.61*** (0.14) |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 0.91*** (0.12) | -0.09*** (0.02) | -0.02** (0.01) | -0.07 (0.07) |

| Conduct | 1.53*** (0.43) | 0.47*** (0.11) | -0.01 (0.02) | -1.58*** (0.18) |

| Piers-Harris | ||||

| Intellectual and School Status | 12.58*** (0.36) | 0.19* (0.07) | 0.11*** (0.02) | 0.41* (0.17) |

| Popularity | 9.48*** (0.33) | 0.14* (0.07) | 0.03* (0.01) | 0.01 (0.12) |

| Happiness and Satisfaction | 8.90*** (0.20) | 0.10* (0.04) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.09) |

| Physical Appearance and Attributes | 9.27*** (0.43) | 0.44*** (0.09) | 0.08*** (0.02) | -0.07 (0.15) |

| Had 5+ Alcohol Drinks in One Day | -0.01 (0.07) | 0.13*** (0.02) | -0.01* (0.01) | -0.21*** (.05) |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Parental monitoring was negatively associated with RCMAS physiological anxiety, CDI total depression, four of the CDI subscales, conduct disorder behaviors, and heavy drinking. This suggests that as parental monitoring increases, there are significant declines in anxiety and general/specific depression, declines in delinquent behaviors, and declines in excessive drinking. A positive slope was noted for the Piers Harris subscale of intellectual and school status, suggesting that this assessment of self-concept increases as parental monitoring increases.

The interaction between family routines and age within this conditional model was also investigated to test whether the effects of family routines on the outcome variables varied across age. Findings were generally nonsignificant except for a significant interaction between family routines and heavy drinking across age. Results are similar to those shown in Figure 1.

Additional analyses were performed to include the interaction between family routines and parental monitoring into the existing conditional models. Only one of the interactions was found significant (CDI ineffectiveness, p = .01). The addition of the interaction term did not change the overall findings for family routines or parental monitoring (the one exception was for the Piers-Harris popularity subscale and routines, p = .06). Constancy of the conditional models was assessed through the addition of family structure and demographic covariates. All of the original significant findings for family routines and parental monitoring findings were retained except for family routines and CDI interpersonal problems (p = .06).

Mother's Physical Wellness in Conjunction With Family Routines and Parental Monitoring

Both family routines and parental monitoring may be affected by a number of factors, including mothers’ physical wellness due to HIV/AIDS. In other words, when physical wellness is good, both family routines and parental monitoring should increase. However, when physical wellness is poor, routines and monitoring would be expected to diminish. We assessed the relationship between physical wellness, family routines, and parental monitoring through bivariate correlations for the six, 6-month intervals of data available for the study. Mothers’ physical wellness was evaluated using the three MOS 36 subscales, illness status, and the Hamilton Depression Inventory.

Findings showed mothers’ physical wellness was associated with family routines and parental monitoring across time. A number of significant (p </= .05) correlations were noted for the MOS 36 subscales. Family routines were found to correlate with bodily pain on three of the six time-points, suggesting that as bodily pain decreases, family routines increase. Routines were found to correlate with physical functioning on two of the time-points, suggesting that as physical functioning increases, so do routines. In addition, a third finding (marginal at p < .10) was noted. Similar correlations between family routines and vitality were noted for three of the time-points, with higher levels of vitality leading to a greater number of reported routines. Family routines were found to correlate with depression at one time-point (higher levels of depression led to lower routines), and one correlation was noted between routines and the number of self-reported HIV illness symptoms (as the number of symptoms increased, routines decreased). A similar pattern of findings was noted for mothers’ physical wellness and parental monitoring, although to a lesser extent regarding the number of significant (p </= .05) findings. One significant correlation was noted between parental monitoring and physical functioning (as physical functioning increases, so does monitoring), while two correlations were noted between parental monitoring and vitality (greater vitality is associated with higher levels of monitoring).

Given the apparent association between mother's physical wellness and family routines (and to a lesser extent parental monitoring), the wellness items were subsequently added to the conditional models noted earlier (routines only; routines and monitoring) as time-varying covariates to investigate whether the prior findings are tenable. All significant findings for routines and monitoring were retained for both sets of models as summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Family Stability Factors and Child/Adolescent Outcomes

The previous growth models addressing family routines and parental monitoring suggest higher levels of routines and monitoring lead to better child/adolescent outcomes. A further investigation was performed to evaluate the effects of “stability” of these routines and parental monitoring on the same outcomes. Such analyses ask, “Do households that are more stable (i.e., their levels of routines and monitoring, regardless of elevation, vary little across time) yield better child/adolescent outcomes compared to those households that are more variable?” Variability of family routines and parental monitoring were generated by calculating standard deviations across time for the observed data on each case. The resulting standard deviations were then used as fixed effect time-invariant covariates in subsequent runs (the resulting stability measures were also mean-centered).

The “stability” analysis findings are noted in Table 4. Of interest are the findings for stability of family routines and parental monitoring conditional models. No significant slopes for stability of family routines were noted across the models. However, for stability of parental monitoring, a number of significant positive slopes are evident, including most of the CDI subscales and conduct disorder behaviors. This indicates that adolescents in households with greater variability in parental monitoring practices report higher levels of general/specific depression and higher levels of conduct disorder behaviors. Significant negative slopes were noted for the Piers-Harris self-concept measures of intellectual and school status, and happiness/satisfaction. Adolescents in households with greater variability in their parental monitoring were associated with lower levels of self-perceived intellectual and school achievement, and lower levels of happiness and satisfaction. Note that these results remain robust even after inclusion of the family structure and demographic covariates (defined earlier), with two new significant findings for stability of parental monitoring (CDI negative self-esteem; Piers-Harris popularity).

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates, Standard Errors, and Significance Tests for Conditional Growth Models With Stability of Family Routines and Stability of Parental Monitoring as Covariates

| Intercept (SE) | Slope of Age (SE) | Slope of Routines (SE) | Slope of Monitoring (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Behavior Checklist | ||||

| Aggressive Behavior | 12.54*** (1.11) | -0.58** (0.20) | 0.50 (0.38) | 3.28 (2.58) |

| RCMAS | ||||

| Physical Anxiety | 2.37*** (0.30) | -0.05 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.12) | 1.20 (0.79) |

| Worry/Oversensitivity | 3.87*** (0.42) | -0.24* (0.09) | 0.08 (0.14) | -0.21 (0.98) |

| Child Depression Inventory | ||||

| Total | 7.23*** (0.76) | -0.34* (0.16) | 0.04 (0.25) | 5.96*** (1.69) |

| Negative Mood | 1.54*** (0.19) | -0.09* (0.04) | 0.01 (0.06) | 1.04** (0.37) |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.91*** (0.14) | -0.07** (0.03) | -0.02 (0.04) | 0.64* (0.26) |

| Ineffectiveness | 1.56*** (0.22) | -0.02 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.07) | 1.73*** (0.46) |

| Anhedonia | 2.31*** (0.29) | -0.06 (0.07) | -0.01 (0.10) | 2.04** (0.70) |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 0.82*** (0.13) | -0.07** (0.03) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.47 (0.26) |

| Conduct | 1.30** (0.48) | 0.54*** (0.12) | -0.27 (0.18) | 3.83** (1.24) |

| Piers-Harris | ||||

| Intellectual and School Status | 13.01*** (0.38) | 0.09 (0.07) | -0.05 (0.14) | -2.52** (0.96) |

| Popularity | 9.60*** (0.32) | 0.12 (0.06) | -0.02 (0.10) | -1.29 (0.67) |

| Happiness and Satisfaction | 9.05*** (0.21) | 0.06 (0.04) | -0.05 (0.05) | -0.82* (0.35) |

| Physical Appearance and Attributes | 9.51*** (0.43) | 0.38*** (0.08) | -0.01 (0.12) | -1.09 (0.84) |

| Had 5+ Alcohol Drinks in One Day | -0.12 (0.06) | 0.15*** (0.02) | -0.04 (0.02) | 0.24 (0.13) |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

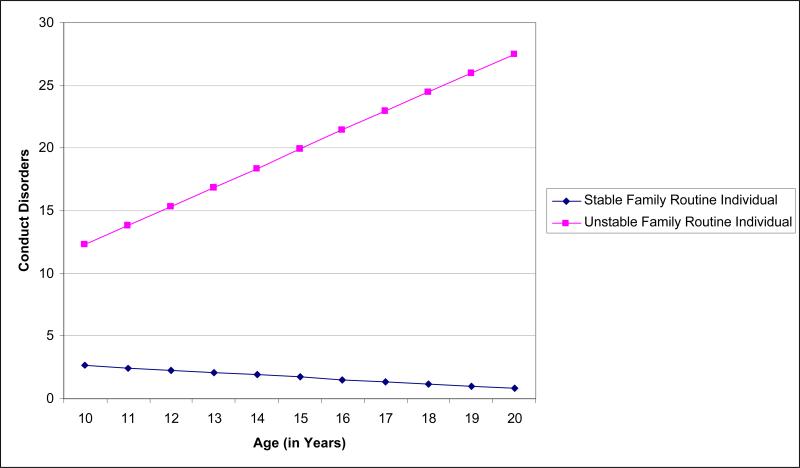

Although stability of family routines failed to yield significant results, it is possible that this covariate's effect varies across age. Therefore, an interaction term between stability of family routines and age was added to the conditional model. The models tested include the fixed effects of age, stability of family routines, stability of parental monitoring, and the interaction of age and stability of family routines. Across the models, three of the outcome measures evidenced significant interactions. Conduct disorder behaviors yielded a significant (p < .01) interaction term, as did the Piers-Harris self-concept subscale of social functioning and popularity, and the Piers-Harris self-concept subscale of physical appearance and attributes (p < .05). Interpretation of these interactions were performed by generating predicted scores using the fixed effect model parameters and plotting low and high values for stability of family routines across age. Per Figure 2, the trajectory for individuals reporting stable family routines do not evidence much linear change over time regarding conduct disorder behaviors. However, the trajectory for those where family routines are highly unstable exhibit increasing conduct disorder behaviors as individuals age. In other words, for older adolescents, higher levels of conduct disorders are evident when family routines are highly unstable. For the Piers-Harris measures (not shown), when family routines are highly unstable, there are notable increases in the social functioning and popularity measure, and in the physical appearance and attributes measure. This suggests that for older adolescents, higher scores on these self-concept scales are evident when family routines are unstable.

Figure 2.

Projected trajectories for individuals reporting low and high stability of family routines by age

Note: Growth curve model estimates used for trajectories: intercept (1.35), age slope (0.54), stability family routines slope (-0.91), stability parental monitoring slope (3.89), interaction of age and family routines (0.21).

The significant findings regarding stability of parental monitoring and outcomes may be affected by mother's physical wellness; is wellness associated with less parental monitoring variability? Using mother's physical wellness variables as separate outcomes (the three MOS 36 subscales, illness status, and the Hamilton Depression Inventory), a series of conditional models were derived using age as a fixed effect covariate with random intercepts and slopes, and stability of parental monitoring as a fixed effect covariate. In addition, the interaction between age and stability of parental monitoring was also part of models. Stability of parental monitoring was not found to be associated with any of the physical wellness variables, nor were any significant interactions noted, suggesting variability in parental monitoring was not associated with mother's physical wellness.

Discussion

Results from this study indicate that the implementation of family routines has a powerful impact on child/adolescent outcomes among families affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. Among families with more frequent family routines, over time adolescents showed lower rates of aggressive behavior, anxiety/worry, depressive symptoms, conduct disorder behaviors, and binge drinking. Moreover, these adolescents also showed increased self-concept scores compared to adolescents in families where there was a lower frequency of family routines. Similarly, parental monitoring appears to have a significant impact on adolescent outcomes over time. As parental monitoring increased, adolescents showed significant declines in anxiety and depressive symptoms, lower conduct disorder behaviors, and decreases in binge drinking, along with increases in self-concept. These findings were found to be robust even after adjustment for family structure, demographics, and mother's physical wellness. Overall, the current study results are consistent with results reported in the literature on general population families (i.e., not affected by parental illness). Analysis of the interaction of family routines and adolescents’ age indicates that adolescents with fewer family routines reported distinct increases in heavy drinking as they got older. This finding suggests frequent family routines remain important throughout mid and late adolescence in reducing the risk of binge drinking.

Both family routines and parental monitoring may be affected by a number of factors, including mothers’ physical wellness due to HIV/AIDS. In other words, when mothers are physically well, it would be expected that they have more energy to sustain family routines and parental monitoring. However, when mothers are ill, routines and monitoring may diminish. In this study, as expected, mothers’ level of illness was associated with family routines and parental monitoring over time, although fewer significant findings were noted for parental monitoring (note that the parental monitoring correlations referred to here do not reflect findings surrounding stability of parental monitoring, which did not yield significant associations as previously reported in the Results). It may be that in the face of declining maternal wellness, other family members play a larger role in monitoring (or not monitoring) adolescents. Overall, as bodily pain decreased and physical functioning and vitality increased, family routines increased. As noted earlier, there has been very little research conducted investigating the effect of parental illness on parenting skills. These findings suggest that mothers living with HIV/AIDS fluctuate in their parenting abilities specific to family routines and parental monitoring based on their physical illness level.

The findings of mothers’ implementation of family routines and monitoring on child/adolescent outcomes led us to consideration of the stability of parental behaviors. Unstable implementation, that is, independability, in and of itself, may constitute somewhat of a risk factor for poorer child/adolescent outcomes. Indeed, it was found that adolescents in families with greater variability in parental monitoring showed higher levels of depressive symptoms and of conduct disorder behaviors, and lower self-concept specific to academic achievement and happiness/satisfaction.

Moreover, the interaction of adolescent age with stability of family routines indicates that, among older adolescents, when family routines were highly unstable, higher levels of conduct disorder behaviors were exhibited over time. This research group has also found that adolescents of mothers living with HIV/AIDS who perceive higher levels of HIV-related stigma towards their mothers report higher participation in delinquent acts than adolescents with lower perceived stigma (Murphy et al., 2006). Thus, the delinquency/conduct disorder symptoms finding here may be partially due to the instability of family routines and parental monitoring, but also to other factors associated with living with a mother with HIV/AIDS. The interaction of age with stability of family routines also showed that older adolescents with unstable family routines had higher scores on the popularity and physical appearance self concept scales. Although family instability would not be expected to be associated with better self concept, many of the items on these scales examine the youth's connection with friends and popularity with peers; thus one plausible explanation for this finding is that as the youth age and transition to late adolescence and young adulthood, those experiencing instability of routines at home may have a propensity to increase their involvement with their friends and peer groups. This may serve as a protective factor for adolescents in families with unstable routines if the youth find support from association with a positive peer group, but could be a risk factor if youth become involved more intensively with deviant peers.

Results of the current study may be useful in developing interventions for mothers living with HIV/AIDS along these same lines. Such interventions may assist mothers in developing simple family routines that can be maintained stably even when they are experiencing physical dysfunction due to illness. In addition, increasing parental awareness of developmental expectations and parenting efficacy can also be implemented within this population. Our results fit well within the organization-developmental framework of resilience (Wyman et al., 2000), with variables such as family routines and parental monitoring acting as protective factors that enhance adolescent outcomes. In terms of intervention strategies, Wyman et al. have suggested a model of cumulative competence promotion and stress protection, focusing on intervention objectives such as access to resources, parental development, health maternal behaviors, and parenting efficacy, with such a model shown to be effective in specific populations (e.g., Sandler et al., 2003). Finally, further investigation of whether families can utilize other support (e.g., other family members) to assist mothers when they are unable to maintain family routines or parental monitoring are needed, to determine if such assistance is sufficient to maintain positive adolescent outcomes when someone other than the mother provides these parenting skills. Furthermore, the results of this study indicate that parenting interventions should emphasize the role of family routines and parental monitoring in reducing heavy alcohol use among adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. Conventional wisdom has long upheld the belief that the peer group exerts the strongest influence on adolescent behavior, but the family is a strong factor in moderating adolescent risk behavior. Binge drinking has related to a decline in relations with family members (Isralowitz & Reznik, 2006).

These results also may guide modification of currently existing evidence based interventions for youth with a terminally ill parent, divorced parents, or a recently deceased parent (e.g., Sandler et al., 2003), to meet the specific needs of families with a parent living with HIV/AIDS. For example, Sandler et al.'s evidence based intervention consists of 12 sessions including parental warmth, parent-child communication, effective discipline, and child coping skills (see also Haine, Ayers, Sandler, & Wolchik, 2008). The intervention could be readily modified to include an emphasis on family routines and monitoring.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, the sample size is fairly restricted, both in size and to one geographical area of the country. Second, although many of the models tested here were significant, random effects findings suggest additional variance could be accounted for by adding more covariates. Even with the main predictors utilized in the study (family routines and parental monitoring), more complex effects could be fit. Thus, the model results presented here are suggestive, not definitive. Third, the study had no control group of children of mothers who were not HIV-infected. Future studies may address these issues, and explore factors that might result in parenting skill limitations besides maternal health, such as multiple doctor appointments, changes in medical routines, etc., that may make it more difficult for mothers to maintain family routines.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant #R01 MH057207-14 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the first author.

References

- Achenbach TM. The Child Behavior Profile: I. Boys aged 6-11. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:478–488. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. The Child Behavior Profile: II. Boys aged 12-16 and girls aged 6-11 and 12-16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:223–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armistead L, Klein K, Forehand R. Parental physical illness and child functioning. Special Issue: The impact of the family on child adjustment and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud SH. Some psychological characteristics of children of Multiple Sclerotics. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1959;21:8–22. doi: 10.1097/00006842-195901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JE, Shagle SC. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggar H, Forehand R. The relationship between maternal HIV status and child depressive symptoms: Do maternal depressive symptoms play a role? Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Jensen EW, James SA, Peacock JL. The family routines inventory: Theoretical origins. Social Science & Medicine. 1983;17:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt P, Weinert C. Children's mental health in families experiencing Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Family Nursing. 1998;4:41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal psychological functioning, family processes, and child adjustment in rural, single-parent, African American families. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1000–1011. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Mounts N, Lamborn SD, Steinberg L. Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development. 1993;64:467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck FM, Hohmann GW. Parental disability and children's adjustment. Annual Review of Rehabilitation. 1983;3:203–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy A. When, why, how to get your baby into a routine. Working Mother. 1992 July;15:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cates JA, Graham LL, Boeglin D, Tiekler S. The effect of AIDS on the family system. Families in Society. 1990;71:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Champion KM, Roberts MC. The psychological impact of a parent's chronic illness on the child. In: Walker CE, Roberts MC, editors. Handbook of clinical child psychology. 3rd ed. Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 1057–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Volume 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Curry JF, Craighead WE. Depression. In: Ollendick TH, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of child and adolescent assessment. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 1993. pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Derogratis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetski S, Schmale AM, Henrichs M, Carnicke CLM., Jr. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1983;249:751–757. doi: 10.1001/jama.249.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Forehand R, Armistead LP, Morse E, Morse P, Stock M. Mother knows best? Mother and child report of behavioral difficulties of children of HIV-infected mothers. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 1999;21:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra R, Forehand R, Armistead L, Brody G, Morse E, Morse PS, Clark L. Child resiliency in inner-city families affected by HIV: The role of family variables. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38:471–478. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Olson RE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Bearinger LH. Correlations between family meals and psychosocial well-being among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:792–796. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, Curtis LL, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH. Antecedent-consequence conditions in maternal mood and child adjustment: A four-year cross-lagged study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:362–374. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Baker T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:381–390. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Jones DJ, Kotchick BA, Armistead L, Morse E, Morse PS, Stock M. Noninfected children of HIV-infected mothers: A 4-year longitudinal study of child psychosocial adjustment and parenting. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:579–600. [Google Scholar]

- Foxcraft DR. Adolescent drinking behaviour: Family socialization influences develop with age.. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Diego, CA. 1994, February. [Google Scholar]

- Greene Bush E, Pargament KI. Family coping with chronic pain. Families, Systems, & Health. 1997;15:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Grue L, Lærum KT. ‘Doing motherhood’: Some experiences of mothers with physical disabilities. Disability & Society. 2002;17:671–683. [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:754–762. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine RA, Ayers TS, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA. Evidence-based practices for parentally bereaved children and their families. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:113–121. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair EC, Moore KA, Garrett SB, Ling T, Cleveland K. The continued importance of quality parent-adolescent relationships during late adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hall NW. Your baby's amazing memory: New research reveals how much infants remember. Parents Magazine. 1997 March;72:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes L, Smart D, Toumbourou JW, Sanson A. Parental influences on adolescent alcohol use. Australian Institute of Family Studies; Melbourne, Australia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes HM. Measures of self-concept and self-esteem for children ages 3 - 12 years: A review and recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 1984;4:657–692. [Google Scholar]

- Isralowitz R, Reznik A. Brief report: Binge drinking among high-risk male and female adolescents in Israel. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:845–849. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KC, Crockett LJ. Parental monitoring and adolescent adjustment: An ecological perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PL, Flake EM. Mental depression and child outcomes. Psychiatric Annals. 2007;37:404–410. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Brody G, Armistead L. Parental monitoring in African American, single mother-headed families: An ecological approach to the identification of predictors. Behavior Modification. 2003;27:435–457. doi: 10.1177/0145445503255432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Rakow A, Colletti CJM, McKee L, Zalot A. The specificity of maternal parenting behavior and child adjustment difficulties: A study of inner-city African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:181–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase LM. Routines to the rescue. Parents Magazine. 1999;74:119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Forehand R, Brody G, Armistead L, Simon P, Morse E, Clark L. The impact of maternal HIV-infection on parenting in inner-city African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Interview Schedule for Children. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Beck AT. An empirical clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. In: Schulterbrandt JG, Raskin A, editors. Depression in childhood: Diagnosis, treatment, and conceptual models. Raven Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lamping DL, Sewitch M, Clark E, Ryan B, Gilmore N, Grover SA, Williams JL, Meister C, Hamel M, Di Meco P. HIV-related mental health distress in persons with HIV infection, caregivers, and family members/significant others: Results of a cross-Canada survey.. International Conference on AIDS; Florence, Italy. 1991, June. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Feigelman S, Stanton B. Perceived parental monitoring and health risk behaviors among urban low-income African-American children and adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linver MR, Silverberg SB. Parenting as a multidimensional construct: Differential prediction of adolescents’ sense of self and engagement in problem behavior. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine & Health. 1995;8:29–40. doi: 10.1515/IJAMH.1995.8.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Prelow HM. Externalizing and internalizing problems in low-income Latino early adolescents: Risk, resource, and protective factors. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24:250–273. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Sexton CC. Maternal drug abuse versus maternal depression: Vulnerability and resilience among school-age and adolescent offspring. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:205–225. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Sloper P, Lewin R. The meaning of parental illness to children: The case of inflammatory bowel disease. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2002;28:479–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Austin EL, Greenwell L. Correlates of HIV-related stigma among HIV-positive mothers and their uninfected adolescent children. Women & Health. 2006;44:19–42. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters LC, Esses LM. Family environment as perceived by children with a chronically ill parent. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1985;38:301–308. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers EV. Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale: Revised Manual 1984. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D. The practicing and representing family. In: Sameroff AJ, Emde R, editors. Relationship disturbances in early childhood. Basic Books; New York: 1989. pp. 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Kobak KA. Hamilton Depression Inventory: A self-report version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children's manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rodin G, Voshart K. Depression in the medically ill: An overview. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143:696–705. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.6.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, Kwok OM, Haine RA, Twohey-Jacobs J, Suter J, Lin K, Padgett-Jones S, Weyer JL, Cole E, Kriege G, Griffin WA. The family bereavement program: Efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:587–600. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt N. Uses and abuse of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Singer J, Willett J. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Soliday E. The effects of parental chronic kidney disease on the family. Family Relations. 2001;50:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Determinants and consequences of associating with deviant peers during preadolescence and adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1986;6:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Fletcher A, Darling N. Parental monitoring and peer influences on adolescent substance use. Pediatrics. 1994;93:1060–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development. 1992;63:1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass P, Bennett LA, Wolin SJ, Reiss D. The alcoholic family. Basic Books; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson AL, Henry CS, Robinson LC. Family characteristics and adolescent substance use. Adolescence. 1996;31:59–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuifbergen AK. Patterns of functioning in families with a chronically ill parent: An exploratory study. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13:35–44. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytsma SE, Kelley ML, Wymer JH. Development and initial validation of the child routines inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:241–251. doi: 10.1007/s10862-022-10007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Gandek B, the IQOLA Project Group The SF-36 Health Survey: Development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA Project. International Journal of Mental Health. 1994;23:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Maternal depression and its relationship to life stress, perceptions of child behavior problems, parenting behaviors, and child conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16:299–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00913802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SJ, Bennett LA. Family rituals. Family Process. 1984;23:401–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods NF, Haberman MR, Packard NJ. Demands of illness and individual, dyadic, and family adaptation in chronic illness. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15:10–25. doi: 10.1177/019394599301500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsham NL, Compas BE, Ey S. Children's coping with parental illness. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children's coping: Linking theory and intervention. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Cowen EL, Work WC, Hoyt-Meyers LA, Magnus KB, Fagen DB. Caregiving and developmental factors differentiating young at-risk urban children showing resilient versus stress-affected outcomes: A replication and extension. Child Development. 1999;70:645–659. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Nelson K. Resilience as cumulative competence promotion and stress protection: Theory and intervention. In: Cicchetti D, Rappaport J, Sandler I, Weissberg RP, editors. The promotion of wellness in children and adolescents. Child Welfare League of America Press; Washington, D.C.: 2000. pp. 133–184. [Google Scholar]