Abstract

Advances in instrument technology and automation have simplified tasks in laboratory diagnostics reducing errors during analysis thereby improving the quality of test results. However studies show that most laboratory errors occur in the pre-analytical phase. In view of the paucity of studies examining pre-analytical errors, we examined a total of 1513 request forms received at our laboratory during a 3 month period. The forms were scrutinized for the presence of specific parameters to assess the pre-analytical errors affecting the laboratory results. No diagnosis was provided on 61.20% of forms. Type of specimen was not mentioned in 61.60% of the forms and 89.25% of all forms were illegible. Critical results were encountered in 17.30% of patients, and of these 76.60% were not communicated due to incomplete forms. Thus, by following standard operating procedures vigorously from patient preparation to sample processing the laboratory results can be significantly improved without any extra cost.

Keywords: Pre-analytical errors, Automation, Critical result, Quality control

Introduction

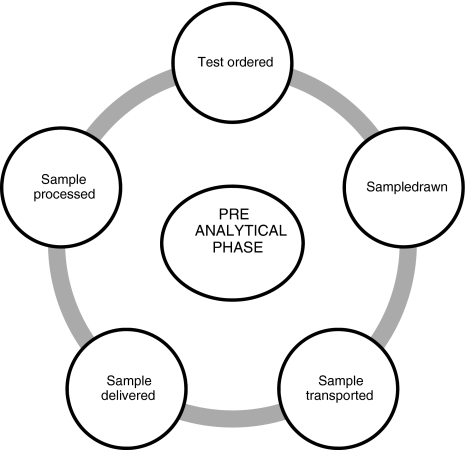

Laboratory testing is a highly multifarious process.This process of clinical laboratory testing comprises of two phases, the analytical and the extra-analytical phase. If we presume the patient care as a cycle of activities or events, errors can occur at any stage starting from the treating physician examining and ordering investigations (pre-analytical stage as shown in Fig. 1), the labs receiving the sample and analysing it (analytical stage) and finally while the reports are communicated to the physician for actions pertaining to the management of the patient (post-analytical stage). Errors at any of these stages can lead to a misdiagnosis and mismanagement and represent a serious hazard for patient health. Automation, databases and computers have greatly simplified many aspects of previously tedious tasks, creating a greater volume of routine work, as well as significantly improving the analytical error rate over time [1]. But the extra-analytical phase (pre-analytical and the post-analytical stage) is still the source of concern as they can lead to unpredictable and unfavourable impact on the well being of patients. Various researchers have reported that 46-68.2% of laboratory errors occur in the pre-analytical phase which is mainly due to lack of standardised protocols for defining and measuring pre-analytical variables [2, 3].

Fig. 1.

Cycle of events in the pre-analytical stage

The last few decades have seen a significant decrease in the rates of analytical errors in clinical laboratories, and currently available evidence demonstrates that the pre- and post-analytical steps of the total testing process are more error-prone than the analytical phase [4]. The increasing attention paid to patient safety, and the awareness that the information provided by clinical laboratories impacts directly on the treatment received by patients, has made it a priority for clinical laboratories to reduce their error rates and promote an excellent level of quality [5]. An appropriate increase in the use of information technology in health care produces a process simplification and could thus result in substantial improvement in patient safety [6]. The errors in the health care can be prevented if we understand the human factors causing them [7].

The present study focuses on the pre-analytical phase, with the aim to calculate rates of these errors at the hospital and targeting their decline in future by recommending some targeted interventions.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a prospective screening of lab request forms, conducted by the department of Neurochemistry during a 3 month period from February 2009 to April 2009 at a tertiary care Neuropsychiatry hospital in India. The screening of the lab request forms was done through some prefixed criteria (Table 1). The data pertaining to these criteria have been developed, recorded and maintained in the registers of Neurochemistry lab. The total number of samples requested were 1536, out of these 23 samples were rejected due to following reasons: six because of absence of lab request forms, thirteen samples rejected due to quality inappropriate (either lipaemic or hemolysed) and four samples rejected due to inappropriate vial. The study sample hence comprised of screening the lab request forms of 1513 study subjects who were subjected to the lab tests at the hospital during the study period.

Table 1.

Prefixed criteria examined on lab request forms

| Prefixed criteria |

|---|

| Registration number of the hospital |

| Name and surname of the patient |

| Age |

| Gender |

| OPD/Ward/emergency |

| Requesting physician’s name & signature |

| Clinical/diagnostic information |

| Diagnosis in abbreviated form |

| Identification of sample |

| Date of sample collection |

| Illegible handwriting |

Critical results in the present study have been defined as: results suggesting that the patient is in imminent danger; unless appropriate therapy is initiated promptly [8]. Good lab practices demand that all critical results be communicated to the respective treating physician to facilitate prompt and appropriate action.

Results

The results of the 1513 requisition forms received in the lab are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Absence of parameters on the lab request forms (n = 1513)

| Prefixed criteria | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient information | ||

| Name of the patient | 0 | Nil |

| Age | 21 | 1.41 |

| Sex | 20 | 1.32 |

| Registration number | 15 | 0.99 |

| OPD, Ward, ICU or Emergency | 54 | 3.6 |

| Clinical information | ||

| Diagnosis wasn’t mentioned | 926 | 61.2 |

| Abbreviated diagnosis | 30 | 1.98 |

| Specimen information | ||

| Type of the specimen | 932 | 61.6 |

| Date of collection | 350 | 23.13 |

| Illegible or difficult to decipher | 1350 | 89.25 |

| Investigation information | ||

| Normal value | 592 | 39.13 |

| Total Abnormal value | 921 | 60.87 |

| Critical value | 261 | 17.25 |

Patient Information

The name of the patient was recorded in all the forms whereas their age was not mentioned in 1.41%, sex of patients was not mentioned in 1.32% and the registration number was missing in 0.99% of the patients. The details pertaining to whether the patient had been registered at the OPD, Ward, ICU or Emergency was missing in 3.6% of the forms.

Treating Physician’s Information

The treating physician’s names were missing in 13.1% of the forms and these were not signed by them in nearly 13.4%.

Clinical Information

Clinical details were illegible or difficult to decipher in 89.25% of the lab request forms. The diagnosis was not mentioned in 61.2% of the patients. Diagnosis was mentioned in abbreviated forms in nearly 1.98%. Of these abbreviated diagnosis nearly 6.6% were not standard abbreviations.

Specimen Information

The type of the specimen was not mentioned in 61.6% forms, date of collection of the specimen was missing in 13%.

Abnormal Values of Lab Tests

These were encountered in 921 study samples, i.e. 60.87% of the total sample. Out of these in 711 cases (77.2%) diagnosis was not mentioned and 27 cases (2.93%) had diagnosis mentioned in abbreviations.

Of the total abnormal values, the Critical results were encountered in 261 patients, i.e. 17.3% of the total study sample. On further evaluation of these critical results, the diagnosis was missing in 194 study samples and 10 had abbreviated diagnosis.

Of these critical results, 76.6% were not communicated to the treating physician for different reasons.

Discussion

Major revolution has been observed in the field of biochemical laboratory testing in the last few decades. The lab medicine plays a pivotal role in the provision of healthcare to the masses and hence there is an ever increasing demand for reliability and accuracy of the lab tests. There are whole gamuts of factors that contribute to accurate test results in the biochemistry laboratories. These factors can be classified into three phases: pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical. The advances in the technology like automation and computerisation of the tests have led to reduction in the errors during analytical phase but there still remains a high level of inconsistency in the total testing process. The major contributors being the pre-analytical errors are complex as they involve numerous steps and various levels of professionals.

To reduce the number of errors in the pre-analytical phase and achieve the standards of high quality, special attention must be devoted to this phase. It is a natural responsibility of the healthcare provider(s) to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of the details of the patient identification and hence this must be done with utmost vigilance making it as less error prone as possible. Further, it is also the direct responsibility of the health functionaries to give the complete information about the presumptive or confirmed diagnosis, in a clear and legible handwriting, avoiding the abbreviations as far as possible. This would justify the relevance of the requested tests and also give a clinical impression to the lab staff as well as ensure promptness of action.

The major pre-analytical errors of concern noticed in our study were that the treating physician’s names were missing in 13.1% of the forms and their signatures were missing in nearly 13.4% of the lab forms. Clinical information was illegible or difficult to decipher in 89.25% of the forms. The diagnosis was not mentioned in 61.2% of the lab request forms and the information pertaining to the type of specimen was missing in 61.6% forms. Since majority of the errors in the total testing phase originate in the pre-analytical phase, these errors can be minimised by ensuring that the specimens are obtained from the right patient [9].

Critical results were observed in 17.3% of the total study sample. Of these, 76.6% were not communicated to the treating physicians either due to lack of the details of the treating physician or due to the non availability of the treating physician at that point of time. Even in those request forms where the details of the physician was available repeated phone calls had to be given to communicate the results to them. Some of the request forms were deficient in indicating whether the sample is from the OPD/Ward/ICU/Emergency thus preventing the appropriate medical intervention.

A similar study done by Nutt et al. [10] reported that the information regarding the details of treating physician was missing in 61.2% the details of diagnosis was not indicated in 19.1% whereas in 80.9% where the diagnosis was mentioned, 37.3% were in the abbreviated forms. In total of 151 Critical results encountered in their study 19.9% were not communicated to physicians. Misinterpretation of laboratory test results or ineffectiveness in their notification can lead to diagnostic errors or errors in identifying patient critical conditions. Incorrect interpretation of tests and the breakdown in the communication of critical values are preventable errors, hence every effort should be made to prevent the types of errors that potentially harm patients. Clinical laboratories can therefore work to improve clinical effectiveness, without forgetting that everything should be designed to provide the best outcomes for patients [11].

The limitation of our study is that the pre-analytical variables like patient preparation, patient drug intake, diet, timing of sampling and application of tourniquet have not been included as this is a hospital based laboratory where samples are received from patients attending OPD or admitted in IPD. Therefore, along with sample collection form, only those pre-analytical variables pertaining to samples were considered which were under supervision of lab personnel. However, the hospital follows Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and has well defined Standard and Operating Procedure (as a part of undergoing NABH preparation of IHBAS) for sample collection in the form of sample collection manual which deals with all the pre-analytical variables like usage of right sample collection tube, proper quantity of sample, non hemolysed and lipaemic sample. Also laboratory personnel sensitize the doctors and nursing staff regarding these pre-analytical variables regularly. Rest of the pre-analytical variables like proper transport, proper sample collection tube, quality and quantity of sample are taken care of and supervised in the laboratory at the time of receiving the samples.

In the recent times of high quality patient centred needs, the frequency of errors and mistakes in the pre-analytical phases of lab investigations must be minimised. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that processing incomplete lab request forms may lead to misinterpretation of results causing a serious impact on patient care. New accreditation standards which encompass the adoption of suitable strategies for error prevention, tracking them and controlling them, clearly spelled out specifications regarding the pre-analytical errors and enhanced communication among the health care providers would definitely enhance the reliability and accuracy of the lab tests.

References

- 1.Sharma P. Editorial pre-analytical variables and laboratory performance. Ind J Clin Biochem. 2009;24(2):109–110. doi: 10.1007/s12291-009-0021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plebani M. Errors in clinical laboratories or errors in laboratory medicine? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44(6):750–759. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lippi G, Guidi GC, Mattiuzzi C, Plebani M. Preanalytical variability: the dark side of the moon in laboratory testing. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44(4):358–365. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plebani M. Exploring the iceberg of errors in laboratory medicine. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;404(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sciacovelli L, Plebani M. The IFCC Working Group on laboratory errors and patient safety. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;404(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lippi G. Governance of preanalytical variability: Travelling the right path to the bright side of the moon? Clin Chim Acta. 2009;404(1):32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reason J. Human errors: models and management. West J Med. 2000;172:393–396. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.6.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunderg GD. When to panic over abnormal values. Med Lab Obs. 1972;4:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Da Rin G. Pre-analytical workstations: a tool for reducing laboratory error. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;404(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nutt L, Annalise EZ, Rajiv TE. Incomplete lab request forms: the extent and impact on critical results at a tertiary hospital in South Africa. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45:463–466. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.007252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piva E, Plebani M. Interpretative reports and critical values. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;404(1):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]