Abstract

Background:

The overall rapid change in the socio-demographic pattern of the Saudi Arabian community, especially the changes concerned with women’s education and work will be an important factor in changing fertility beliefs and behaviors with more tendencies to birth spacing and, consequently, the use of contraceptives.

Objectives:

The study aimed to identify the perception of Saudi women regarding the use of contraceptives

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among Saudi women attending primary care centers of Al-Qassim Region. A structured questionnaire was developed to cover the research objectives. The dependant variable was the utilization of contraceptive methods and the socioeconomic variables were the independent variables.

Results:

The results identified the low knowledge level of the participant women regarding the variety of contraceptive methods. Most participants and their husbands showed acceptance to the use of contraceptives for birth spacing. They preferred birth interval of 2–3 years. They intended to have from 5 to 10 children. There was a significant increase in contraceptive use among working women, 30 years and older, with a higher level of education, and those having a large number of children. Multiple regression models revealed that the significant determinants of the use of contraceptives were women’s working and education. The study recommended sustained efforts to increase awareness and motivation for proper contraceptive use.

Keywords: Contraceptives, Birth interval, Saudi Arabia, Al-Qassim

Introduction

A distinguishing feature of the Saudi Arabian population is their desire for large families.(1) They have a high birth rate and a high total fertility rate relative to those of developed countries; however, the last few years have shown a marked drop in both rates.(2) The use of contraceptives has been recognized as a key element in reducing fertility for all age groups in many developing countries.(3–5) Review of literature shows that the advantages of proper child spacing are enormous, as a high fertility rate has been linked with underdevelopment in developing countries.(6) Birth spacing has been identified by the World Health Organization as one of the six essential health interventions needed to achieve safe motherhood.(7)

Studies indicate that the total fertility rate of a nation is inversely related to the prevalence rate of contraceptive use.(8) The overall rapid change in the socio-demographic pattern of the Saudi Arabian community, especially the changes concerned with women’s education and work, will be an important factor in changing fertility beliefs and behaviors with more tendencies to birth spacing and, consequently, the use of the contraceptives.(9) It is interesting to identify the perception of Saudi women regarding contraceptive use and the socio-demographic values that affect this perception. Such information would help health care managers to evaluate and promote the quality of the provided services. This study aimed to indicate answers to the following questions: What knowledge do women have about contraceptives? What are their attitudes towards fertility and their acceptance of contraceptive use? What are the reasons of use and non-use of contraceptives? Is there any correspondence between women’s socio-economic characteristics, contraceptive knowledge, and use?

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the governmental primary health care centers in Al-Qassim Region. Every member in the community has a health record maintained at the primary care center that serves his/her region of residence. In Saudi Arabia, the contraception services are not provided at the level of primary care.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study among women attending governmental primary care centers in Al-Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. Recruitment was done for Saudi women who had ever been married, aged from 18 to 49 years and who have had at least one child. Attendants of primary care centers were members of the different social strata of the community.

Variables

The conceptual framework applied in this study was based on the Andersen and New-man’s predisposing enabling need explanatory model for health services need.(10) The dependant variable in this study was the utilization of contraceptive techniques. The predisposing variables were age, education level, current work status, average monthly income, family size, history of contraceptives use, and knowledge and attitudes towards the use of contraceptives.

Socio-demographic variables

The age of the participants at the time of the interview was recorded in complete years and identified as the younger age group (18–29 years) and the older age group (30–49 years).

Educations was defined as a completed level: Score ‘0’ (no education), ‘1’ (completed primary school), ‘2’ (completed high school) and ‘3’ (completed university).

Monthly income was scored according to the participants’ report: Score ‘0’ for low, ‘1’ moderate, ‘2’ high and ‘3’ very high.

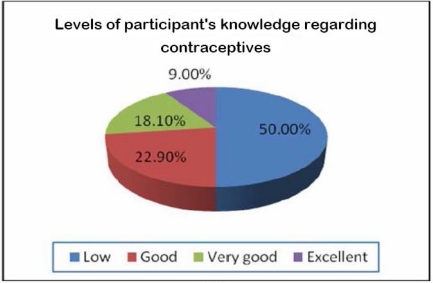

Knowledge: Knowledge was defined according to the participant’s response to a question: “What do you know about the following contraceptive methods: oral pills, intrauterine devices, injections, male condom, diaphragm, male sterilization, female sterilization plus the traditional techniques: breast feeding, Rhythm and withdrawal). The identification of 2 methods was scored as ‘Low’, ‘good’ for identifying 3–4 methods, ‘very good’ for identifying 5–6 techniques and ‘excellent’ for identifying more than 6 methods.

Attitude: In the sphere of reproduction, two opposite attitudes were detected, fatalism and control. Fatalistic power appeared in the desire to have a large number of children. Control appeared in the motivation towards use of modern contraceptives.

The outcome variable was the use of contraceptives. It was defined as a participants’ state of current or previous use of a modern contraceptive method for a minimum of one continuous year. The state of non-use was scored ‘0’ and termed ‘Non user”, and the state of current or previous use was scored ‘1’ and termed “user”. Non-users were asked about the reasons of non-use.

Sampling design

A multistage sampling process was used. Administratively, Al-Qassim Region is divided into, the capital and 10 governorates. Six governorates are categorized in group A which is larger in population density, and four in group B. Nearly half of the population is located in the capital. Five centers were randomly chosen to conduct the study, two centers from the capital and one center from each selected governorate

Sample size

Sample size was calculated on the assumption that the rate of women aged 18–45 years to the total population was 22.3 % 11, considering a degree of precision 0.05, a design effect 1.8 and non-response rate 10 %. A sample size of 502 married women was decided upon.12 The sample size was distributed with proportional allocation between the sampled primary health care centers.

Data collection

Data collection took place between October 2007 and February 2008. A structured questionnaire was developed to cover the research objectives. The questionnaire was originally developed in English and then translated into Arabic; its validity was reviewed by selected health care experts and professionals and tested on a sample of the target population. Selected women were interviewed by trained female medical students. Women were approached while waiting for services at the primary care centers and given a brief description of the study. If they agreed to participate, the student administered the questionnaire verbally. Almost 10 minutes were needed to complete the questionnaire. The process continued till the required sample size was completed.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed to detect the association between different independent variables and the contraceptive use Independent variables are reference parameterized with the theoretically low risk category serving as reference. All independent variables and socioeconomic variables were entered into simultaneous multiple regression analysis to determine the most important variables considered as predictors for regular using of contraceptive techniques.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table (1). The mean age of the respondents was 33.5±4.1 years. Most of the participants (89.7%) had received education, 17.1 % had university degree while 10.3 % were non-educated. Nearly one quarter (22.7%) of the participants reported a very high monthly income, a high income was reported by 41.0%, and the rest reported a low and moderate income (36.3%). More than half of the participants (58.8 %) were not working at the time of the survey. The median number of participant’s children was 5 with a range from a minimum of one, the eligibility criteria of the participants, to a maximum of 12.

Table (1). Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristic | No. (n= 502) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age group in years | ||

| < 30 | 154 | 30.7 |

| 30+ | 348 | 69.3 |

| Educational level | ||

| Non - educated | 52 | 10.3 |

| < high school | 173 | 34.5 |

| High school | 191 | 38.0 |

| University | 86 | 17.1 |

| Income | ||

| Low & moderate | 182 | 36.3 |

| High | 206 | 41.0 |

| Very high | 114 | 22.7 |

| Work | ||

| Not working | 295 | 58.8 |

| Working | 207 | 41.2 |

| Parity | ||

| 1–3 | 187 | 37.3 |

| 4–6 | 210 | 41.8 |

| 7+ | 105 | 20.9 |

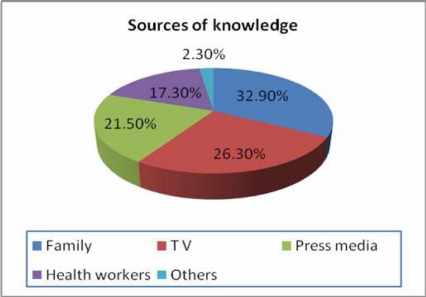

Knowledge on contraception: Fig. (1) shows that half of the participants had low level of knowledge regarding the types of contraceptive methods. More than one fourth of them had the higher scores, very good (18.1 %) and excellent (9.0 %). Oral contraceptive pills were known to all the participants. Intrauterine devices and the male condom were defined by 67.8 % and 46.8% of the participants respectively. The least known temporary method was the cervical diaphragm which was defined by 9.7% of the participants. Sterilization of males or females was reported by only a few. The main source of women’s knowledge was the family members (32.9%), television (TV) and press media came next (26.3 % and 21.5 % respectively). Health workers were reported by 17.3 % of the participants, while the internet was the least source of information, reported by 2.0 % (Fig. 2).

Fig. (1).

Fig. (2).

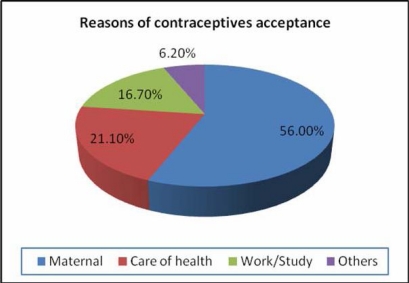

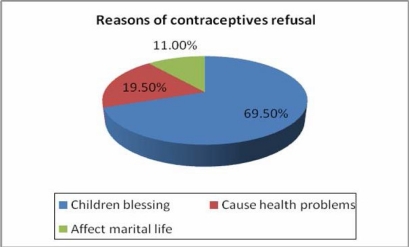

Attitudes towards fertility and contraceptives: Most of the participants (83.7 %) showed acceptance of the use of contraceptives for birth spacing. They reported nearly the same acceptance rate (86.1 %) for their husbands. Table (2) also shows the attitudes of the participants towards fertility as indicated by the number of children and the best birth interval desired by the women. Most of the participants preferred to have 5 to 10 children (70.0 %), and nearly one fourth (23.3 %) to have more than 10 children. Only, 4.8 % of women desired less than 5 children. Regarding the best birth interval, the majority of the participants (62.1%) preferred 2 to 3 years. An interval of more than 3 years was reported by more than one fourth of the participants (25.7 %), only 12.2 % of them preferred an interval of less than 2 years. The reasons for the acceptance of contraceptives use are illustrated in Fig (3). Most participants reported the need to preserve and promote their own health and to take care of the children (56.0% and 21.1 % respectively). Work has been reported by 16.7 % of the participants to be a cause for use of contraceptives, and the rest (6.2 %) reported other causes including economic burden and unstable marital life. Non-use of contraceptives was explained by three main reasons: considering the value of children as being a blessing from God (69.5%), the harmful effect of contraceptives (19.5%), and the negative effect on the marital life (11.0%) (Fig. 4).

Table (2). Participants’ attitudes and use of contraceptives.

| Characteristics | No. (=502) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | ||

| Acceptance to use contraceptives | ||

| Yes | 420 | 83.7 |

| No | 82 | 16.3 |

| Husband’s acceptance to use contraceptives | ||

| Yes | 432 | 86.1 |

| No | 70 | 13.9 |

| Desired number of children | ||

| Less than 5 | 34 | 6.7 |

| 5–9 | 351 | 70.0 |

| 10+ | 117 | 23.3 |

| Desired birth interval | ||

| Less than 2 years | 61 | 12.2 |

| 2–3 years | 312 | 62.1 |

| >3 year | 129 | 25.7 |

| Use of contraceptives | ||

| Non- Users | 277 | 55.2 |

| Users | 225 | 44.8 |

| Modern | ||

| Pills | 158 | 70.2 |

| IUD | 27 | 12.0 |

| Male condom | 16 | 7.1 |

| Total (201) | ||

| Traditional | ||

| Rhythm | 9 | 4.0 |

| Withdrawal | 8 | 3.6 |

| Breast feeding | 7 | 3.1 |

| Total (24) | ||

Fig. (3).

Fig. (4).

Contraceptives use: Out of the total participants, 225 women (44.8%) were using or had used a contraceptive method continuously for at least one year (Table 2). Three modern methods of contraception were used by 201 participants or 89.3% of the users. The oral pills were the most commonly used method, with 70.2% users primarily depending on them. The intrauterine device was the next, and used by 12.0 % of the users. The male condom was the last and least used method (7.1 %). Regarding traditional contraceptive methods, 10.7% of the users depended on these methods regularly. The three traditional methods used were reported as rhythm, withdrawal and breast feeding by 4.0%, 3.6% and 3.1%, respectively. Concerning the use of contraceptives in relation to the participants’ socioeconomic level studied variables, Table (3) shows that contraceptives use by women 30 years and older was significantly more (43.7 %) compared to the younger age group (27.9 %) (OR: 2.0; P < 0.001). Utilization of contraception also increased significantly with the increasing level of education. Women with the highest level of education used contraceptives more than twice (OR=2.7) than the non-educated ones. Concerning the association of participants’ level of monthly income, the Chi square for linear trend analysis was not conclusive. On comparing the women who were at work and those who were not working, the working women showed significantly more use of contraceptives, about four times (OR=3.6), than non- working women. Women with higher parity (7 and more) were using contraceptives twice as much as those with 1–3 children. Table (4) shows the results of multivariate logistic regression analyses of all studied socioeconomic variables, only two variables were significantly associated with the contraceptive use: women’s work (Adjusted OR 2.6) and ‘women’s education (Adjusted OR 2.1).

Table (3). Use of contraceptives by various socio-demographic characteristics.

| Characteristics | Users (n= 225) | Non Users (n= 277) | X 2 (P value) | OR (95 % C I) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Age group in years | ||||||

| < 30 | 43 | 27.9 | 111 | 72.1 | 11.2 (0.001) | 1# |

| 30+ | 152 | 43.7 | 196 | 56.3 | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)* | |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Non educated | 17 | 32.7 | 35 | 67.3 | 7.80@ (0.005) | 1# |

| Primary school | 73 | 42.2 | 100 | 57.8 | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) | |

| High school | 86 | 45.0 | 105 | 55.0 | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) | |

| University | 49 | 57.0 | 37 | 43.0 | 2.7 (1.3–5.9)* | |

| Income | ||||||

| Moderate | 78 | 42.9 | 104 | 57.1 | 2.95@ (0.085) | N S |

| Good | 85 | 41.3 | 121 | 58.7 | ||

| Very good | 62 | 54.4 | 52 | 45.6 | ||

| Income Moderate/good | ||||||

| Very good | 163 | 42.0 | 225 | 58.0 | 5.46 (0.019) | 1# |

| 62 | 54.4 | 52 | 45.6 | 1.7 (1.1–2.6)* | ||

| Work | ||||||

| No | 105 | 35.6 | 140 | 64.4 | 38.9 (0.001) | 1# |

| At work | 90 | 43.5 | 42 | 56.5 | 3.6 (2.3–5.4)* | |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1–3 | 68 | 36.7 | 119 | 63.6 | 6.56 (0.01) | 1# |

| 4–6 | 70 | 33.3 | 140 | 66.7 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | |

| 7+ | 57 | 54.3 | 48 | 45.7 | 2.1 (1.2–3.5)* | |

Reference group @ Chi square for trend

NS: non significant

Table (4). Multivariate logistic regression analysis of independent variables related to contraceptives use among the participants.

| Variables | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95.0 % CI for Adjusted OR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work (No work)# Working |

0.003 | 2.6 | 1.4–3.7 |

| Education (less than university) # University |

0.04 | 2.1 | 1.2–4.8 |

| Age group (less than 30)# 30 + |

0.46 | 1.9 | 0.4–8.6 |

| Income (moderate/high)# High + |

0.89 | 1.1 | 0.4–2.5 |

| Parity (1–3 children) # 4+ |

0.93 | 1.1 | 0.3–3.4 |

Reference group

C I: Confidence Interval

Model Significance: 0.003

Discussion

Contraceptive use has increased in nearly every country in recent decades.13 It was interesting to explore the perception and use of contraceptives among Saudi women. The results identified the poor knowledge regarding the simple variety of contraceptive methods. However, oral contraceptive pills were known to all participants. This could be attributed to the main source of knowledge, that is the family members, who share their limited individual experience. This is consistent with other Saudi studies that have reported the popularity of oral pills.(14–15) We found a limited role of the health workers in providing the information about contraception, which reflects the conservative culture of the community and the power of the family. Recent population surveys have reported that in 37 out of 60 developing countries surveyed, 95% of married women knew at least one contraceptive method (modern or traditional).(16–17) The knowledge gap restricts women’s choice for the use of contraceptive. The international contraceptive knowledge and awareness study(18) conducted among 7,000 women aged 16 to 40 years from 14 countries, has revealed the failure of women to take advantage of new contraceptive methods, their contraceptive knowledge rarely stretching beyond the pill. Most importantly, the survey revealed that all women benefit from full information from their doctors about every contraceptive option.

Two opposite attitudes regarding contraceptive use were detected by the participants during the current study. On one hand a very high acceptance rate of the participants and their husbands for the use of contraceptives for birth spacing, mainly to preserve maternal and child health. A period from 2–3 years was the preferred birth interval. This period coincides with the Islamic teachings regarding the birth rate. Few recent studies have discussed the birth intervals among the Saudi population and have concluded similar results. The first study(9) was a house-to-house survey conducted in a rural area north west of Riyadh in the year 1995, and reported the existing mean birth interval of 31.2±10.1 months that increased with the increasing age of the women. Two studies, conducted in AlKhobar, the urban Eastern Region, reported that the existing mean preceding and succeeding birth intervals of studied children were 26.2 and 28.2 months, respectively.(17) A birth interval of 2–3 years was indicated as the preferred interval by another study.(15) One study that used Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program data from 18 countries found that children born 3 years or more after a previous birth were healthier at birth and more likely to survive at all stages of infancy and childhood through age five.(19) On the other hand the participants that responded to the question about the number of children they intended to have, the majority indicated to have at least 5 and up to 10 children, which means that the woman would not stop having children throughout her reproductive life. Although they accept the concept of birth spacing and the use of contraceptives in order to have the desired interval, this does not mean having fewer children. This high fertility attitude is attributed to the indigenous culture in favor of large families(1); it also coincides with the Islamic religion which rejects the concept of limiting the family size. However, globally, a growing percentage of married women want to stop having many children; the family size that women consider ideal is falling.(4)

Our results show 40% of the participants using or have used modern contraceptives for at least one continuous year, which is a higher percentage of conceptive use than the recent reports about Saudi Arabia(4) indicating 31.8% for all types use, and 28.5% for use of modern contraceptives. This study’s higher rate might be attributed to the population sample that was selected on the community basis rather than the official governmental data. The use of contraceptives is free among the Saudi Arabian population who obtain a different variety of contraceptive health service. Moreover, the contraceptives are available over the counter in the Kingdom. This might add to underestimation of the realistic contraceptives use. However, the user’s rates of the studied participants were still lower than the world reported rates (63.1 %) and lower than those reported in developed countries (67.4 %).(20) Children are a blessing from God was the main reason for the refusal of contraceptives use. This reflects the impact of the Islamic culture; however, nearly one third of the participants raised the question of the impact of contraceptives use on women’s health and marital life, which directs our attention to the misconceptions regarding contraceptives in the culture. Compared with nearby Islamic Arab countries which are supposed to be the same culture, there was a variation in the use of contraceptives. The majority showed a higher user rate than Saudi Arabia, ranging from 43.2% in Qatar, 58.3% in Syria and 61.8% in Bahrain; only two countries reported lower rates: United Arab Emirates (27.5%) and Yemen (23.1%).(20) This variation could be attributed to the variation in the local culture of these countries towards contraceptive use.

Concerning the ranking of the most commonly used methods, our results are consistent with the reported data about Saudi Arabia(4) in which oral contraceptives came on the top followed by intrauterine devices (IUDs), female sterilization and the use of the male condom. However, female sterilization was not reported in this study. In developing countries, four modern contraceptive methods, oral contraceptives, IUDs, injectables, and female sterilization are the most widely used methods among married women.(21) The last two methods were not reported by our participants, which could be attributed to the participants’ traditions and Islamic culture that accept only temporary delay of pregnancy and reject permanent sterilization. The official data reports are usually dependent on hospital based records.

Concerning the male use of contraceptives, the results showed a discrepancy between the husbands’ acceptance of the birth spacing and the low use of male contraceptives (condoms), which could be attributed to the traditional cultures or may reflect underreporting due to shy users.(22) In developing countries, condoms and male sterilization are among the least used of all contraceptive methods. The reverse is true in developed countries, in which condoms are the major method of family planning.(4) However, the recent United Nation’s report (2007) about contraceptive use worldwide showed more use of condoms among the Saudi population and to be the second most common used method after pills, which matches the trend of developed countries.(20)

There was a strong association between the participants’ age (30+ years) and the use of contraceptives. This could suggest that the mother may be satisfied by the number of children she has had and feels that she needs more spacing for preserving her health. This notion is consistent with the results of the indigenous study in a rural area near Riyadh(9), which reported that parity and current age of the mother were the only significant predictors of birth intervals. The use of modern contraceptive methods has been successfully promoted for child spacing and limiting family size among older married women with children in developing countries.(23–24)

The use of contraceptives by women younger than 30 years could be attributed to their desire to complete their studies or to keep working which were the reported reasons for contraceptives use by more than one third of the study participants. The results of this study were also consistent with published reports showing more contraceptives use among women at the higher economic level.(23)

Significantly more use of contraceptives was reported by the participants with higher education, better knowledge, and those working. It was confirmed that education generally exerts a negative influence on fertility; secondary analyses of the data of one Egyptian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) documented the negative impact of maternal lack of education on the low use of contraceptive services.(26) Through education, women have acquired the cognitive and communication skills that shape their attitudes, family style and interactions with the modern world. These appeared in a strong association between the use of services and education.(27) The secondary analysis of a sub-sample of a national demographic survey (Zaire, 1999) concluded that age at marriage and a woman’s education are apparently the most important determinants of low fertility behavior.(28) Women’s work is strongly linked to the contraceptives use.(27) However, the previous national study (Saudi Arabia)(28) concluded that there was no significant effect of women‘s participation in the labor force upon fertility because of the wide variety of privileges given to working women. Multivariate analysis revealed women’s work and education had an overwhelming impact over other variables introduced in the model. A rapid change in the community in the last decade with great expansion in women’s education, and consequently women’s work could explain the evolution of these two variables as the main determinants of contraceptive use.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The present study reveals a low knowledge of the variety of contraceptive techniques. The participants showed high intention to use contraceptives to prolong birth intervals, and low use of contraceptives compared with the user rates of the world and developed countries. The significant determinants of contraceptives’ use include women’s age, knowledge, education, parity and work. Hence, we recommend sustained efforts to raise awareness and motivation for proper contraceptive use. This can be brought about by facilitating access to more information, education and communication with the couples in reproductive age.

References

- 1.Farrag OA, Rahman MS, Rahman J, Chatterjee TK, Al-Sibai MH. Attitude towards fertility control in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 1983;4(2):111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Population Prospects, Int . Highlights. United Nations; New York: 2006. 2007. revision. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adinma B. An overview of the global policy consensus on women’s sexual and reproductive rights: The Nigerian perspective. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;(Suppl. 1):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Information and Knowledge for Optimal Health (INFO) Project . Center for Communication Programs, The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health; 111 Market Place, Suite 310, Baltimore, Maryland 21202, USA. Volume XXXI, Number 2, Spring 2003, Series M, Number 17, Special Topics. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368:1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obisesan KA, Adeyemo AA, Fakokunde BO. Awareness and use of family planning methods among married women in Ibadan, Nigeria. East Afri Med J. 1998;75(3):135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chichakli LO, Atrash HK, Musani AS, Johnson JT, Mahaini R, Arnaoute S. Family planning services and programmes in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6(4):614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauldin WP, Sinding SW. Review of existing family planning policies and programs: lessons learned New York. Population Council; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Nahedh NNA. The effect of sociodemographic variables on child-spacing in rural Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5(1):136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutton D. Financial, organizational and professional factors affecting health care utilization. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23(7):721–35. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Census Bureau International Data Base . Midyear Population, by Age and Sex. Saudi Arabia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies A practical manual. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Population Reference Bureau . Family Planning Worldwide 2008 Data Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabbar FA, Wong SS, Al-Meshari AA. Practice and methods of contraception among Saudi women in Riyadh. Fam Pract. 1998;5(2):126–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/5.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasheed P, Al-Dabal BK. Birth interval: perceptions and practices among urban-based Saudi Arabian women. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13(4):881–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akakpo B. Safer young motherhood in Ghana. Planned Parenthood Challenges. 1998:19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bella H, Al- Almaie Sm. Do children born before and after adequate birth intervals do better at school? J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51(5):265–70. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The XVIII FIGO World Congress of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 5th to 10th November 2006.

- 19.Information and Knowledge for Optimal Health (INFO) Project . Center for Communication Programs, The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 111 Market Place, Suite 310, Baltimore, Maryland 21202, USA. Volume XXX, Number 3, summer 2002, Series L, Number 13, Issues World health. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Contraceptive Use 2007 . United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenny L. Contraception, sterilization and termination of pregnancy. In: Luesley DM, Baker PN, editors. Obstetrics and Gynecology An evidence based text book for MRCOG Arnold. 1st edition. London: 2004. pp. 514–523. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashmi SS. “Shy / Silent Users of Contraceptives in Pakistan.”. Pakistan. 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Development Review, 35: 705–17 [PubMed]

- 24.Blanc AK, Way AA. Sexual behaviour and contraceptive knowledge and use among adolescents in developing countries. Stud Fam Plann. 1998;29:106–116. doi: 10.2307/172153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleland J, et al. The Determinants of Reproductive Change in Bangladesh: Success in a Challenging Environment. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibnouf AH, van den Borne HW, Maarse JAM. Utilization of family planning services by married Sudanese women of reproductive age. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13(6):1372–81. doi: 10.26719/2007.13.6.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin TC. Women’s Education and Fertility. Results from 26 Demographic Health Surveys. Stud Fam Plan. 1995;26(4):187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dandash K, Refaat A. Understanding Demographic Behavior in Egypt; Studies from the Demographic and Health Survey, 1995” Final Report. Sep, 1998. Impact of women’s education on reproductive health and child survival; pp. 2–24. National Population Council. Editor: Scott Moreland. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khraif Rshood M. Fertility in Saudi Arabia: levels and determinants. A paper presented at: XXIV General Population Conference Salvador; Brazil. Aug 18– 24, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapiro D, Tambashe BO. The impact of women’s employment and education on contraceptive use and abortion in Kinshasa, Zaire. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25(2):96–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]