Abstract

Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) is an inflammation-related cytokine. Its expression in the brain increases under conditions of neurodegenerative diseases and injuries. Previous studies have shown that genomic alterations of TGF-β1 expression in the brain cause neurodegenerative changes in aged mice. The present study revealed that increased production of TGF-β1 in transgenic mice resulted in gliosis at young ages. In addition, the increased TGF-β1 augmented the expression of some key subunits of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the hippocampus. Treatment of cultured hippocampal neurons with TGF-β1 facilitated neurite outgrowth and enhanced glutamate-evoked currents. Together, these data suggest that increased TGF-β1 alters ionotropic glutamate receptor expression and function in the hippocampus.

Keywords: Cytokine, astrocytes, microglia, glutamate receptor, neurodegeneration

Introduction

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is an injury-related cytokine that exerts multifaceted functions in the developing and mature brain. Specifically, it is involved in the regulation of neuronal survival [1,2], migration [3,4], astro-cyte development and differentiation [5], and cerebral gene expression [6]. In the central nervous system (CNS), the expression of TGF-β1 increases acutely after various brain injuries including ischemia, trauma and encephalitis, or chronically during the process of neurodegenerative illnesses [7,8,9]. The collected data suggest that TGF-β1 is important in orchestrating brain's response to injury and/or aging. However, the role of TGF-β1 in the regulation of central synaptic transmission remains unknown. The major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian CNS is glutamate, which produces fast synaptic signalling through ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), including α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid (AMPA) receptor and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. A variety of brain diseases are associated with alterations in the function and/or changes in the expression of iGluR complexes at glutamatergic synapses. For example, dysregulation of NMDA receptor activity is involved in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia [10]. Excessive activation of certain AMPA receptors contributes to both acute CNS injuries such as brain ischemia [11] and chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[12].

Inflammatory mediators contribute to the modulation of iGluRs in the cortex and hippocampus. For instance, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [13,14] and interleukin (IL)-1β [15] modulate hippocampal AMPA receptor trafficking and/or expression. In particular, TGF-β1 modulates NMDA receptor mediated excitotoxicity [16,17]. We therefore hypothesized that TGF-β1 may regulate the expression of iGluRs in the hippocampus. In the present study we examined the expression levels of iGluRs in the hippocampus of mice overexpressing TGF-β1. Our studies revealed that chronically increased TGF-β1 causes an upregulation of AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits in the hippocampus. In addition, application of TGF-β1 effectively increased glutamate -evoked currents in cultured hippocampal neurons.

Materials and methods

Transgenic mice

The TGF-β1 transgenic mice (line T64 [18], hereafter called TGF-β1 mice) used in the present study were the 2-month-old heterozygous. The line T64 was engineered to constitutively express active form of porcine TGF-β1 using a GFAP promoter [2,18,19,20,21]. Non-transgenic litter-matched wild type (WT) mice served as controls. In accordance with the animal use protocol approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Hospital for Sick Children, mice were genotyped by means of PCR assay of the tail tissue. TGF-β1 mice and their WT littermates were anesthetised using halothane and then decapitated. The brains of some mice were quickly removed and the neocortex and hippocampi were isolated, frozen and stored at -80° C. Some brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldyhyde (PFA).

Western Blot

The general procedure of Western blotting was carried out as previously described [22]. Briefly, the cortical and hippocampal tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer containing 1% Non-idet P-40, 0.1% Sodium dodecyl sulphate, 0.5% Deoxycholic acid and protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were assayed by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Protein samples (30–60 μg) were fractionated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk powder in TBS-T (0.1% Tween 20, 1mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 150mM NaCl) or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS-T and were incubated at 4°C overnight in primary antibodies. The commercially available primary antibodies used included anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:50,000, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-GluR2 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-GluR4 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-NMDAR1 (1:500, BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA), anti-NMDAR2A/B (0.3 μg/mL, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), anti-porcine TGF-β1 (1:2,000, Cell Sciences, Inc., Canton, MA, USA), anti-β-actin (1:5,000, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:5000, Abcam Inc.). β-actin or GAPDH were used as loading controls. After three washes in TBS-T, blots were incubated with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 hours and proteins of interest were detected with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The blotting films were scanned using GeneSnap (Syngene, Synoptics Ltd., Cambridge, UK) acquisition software and band densities were quantified using the GeneTool (Syngene, Synoptics Ltd.) program. The assay was repeated at least 2-3 times for each antibody tested. Values of the band density were normalized to the level of respective β-actin or GAPDH.

Cell Cultures

Time-pregnant Wistar rat (Charles River, St. Constant, QC, Canada) was anesthetised using isofluorane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Rat fetus at embryonic day 18 (E18) were taken out. For primary culture of astrocytes, the neocortex was quickly dissected from the brain of rat fetus and mechanically triturated. The dissociated neocorticial cells were cultured in Dulbecco's MEM (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Until 75% confluency, the cells were stripped from the dish and re-plated on poly-D-lysine (Sigma) coated glass coverslips. More than 95% of the cells grown on the coverslips were astrocytes. The general procedure for culturing hippocampal neurons was the same as previously described [22]. Briefly, the hippocampi were isolated from the fetus’ brain and put in plating medium, consisting of B27-supplemented Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), with 0.5 mM L-glutamine, 25 μM glutamic acid, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.5% FBS. The hippocampal tissues were gently and mechanically triturated without enzymatic treatment. Dissociated neurons were seeded on poly-D-lysine coated 35 mm Nunc culture dish (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), or on top of cultured astrocytes that grew on glass coverslips. After overnight incubation (37°C, 95% air and 5% CO2), two-thirds of the medium were replaced with maintenance medium made up of Neurobasal medium, 0.5 mM L-glutamine and 2% B-27 (1:50) supplement. The cultured neurons together with astrocytes were used for immunostaining on 7th day in vitro (DIV). The hippocampal cells that were not co-cultured with astrocytes were grown over 12 days and the medium was replaced every 3-4 days. Under such culture conditions, more than 96% of dissociated hippocampal cells left in the dish were neurons with few astrocytes [22]. These hippocampal neurons were treated with fresh TGF-β1 (4 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) on the first day of culture and were treated continuously by adding TGF-β1 to the cultured medium every 3 days when changing the culture medium.

Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

Immunocytochemical procedure was performed as previously described [22]. For immunohisto-chemistry, fixed brain specimens were cut using a 1000 Plus Vibratome (Pelco 102, Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA, USA) into 40-μm free-floating sections. Tissue sections were permeabilized in 0.25% Triton X-100, blocked in 10% normal serum in 0.25% Triton X-100 for 2 hours, washed with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight. After three washes with PBS, Cy3- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) were added for incubation at room temperature for 2 hours. When necessary, the process was repeated for double labelling of another primary antibody. We repeated the immunohistochemical assays of each protein in brain tissue sections of 2–4 mice. Primary antibodies used in immunostaining included anti-CD11b (1:150, AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK), anti-GFAP Cy3 conjugate (1:1,000, Sigma-Aldrich), and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2, 1:400, Millipore). Confocal images of stained brain tissues were captured using a 40× lens in a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope attached to Zeiss LSM510 scanning unit (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). The visual field was randomly moved to a site of the cell-culture or tissue section. Digital images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) software.

Whole-cell Patch Clamp Recording

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed in cultured hippocampal neurons on the 11th and/or 12th DIV unless otherwise specified. All electrophysiological measurements were performed at room temperature (∼24°C) using a MultiClamp 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). During recordings, the cultured cells were bathed with an extracellular solution (ECS) composed of (in mM): 154 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 5 KCl, 5 HEPES, 10 Glucose, 0.001 tetrodotoxin (Alomone Labs Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel), with pH 7.4 and osmolarity ∼315 mOsm. Cells in control and TGF-β1 treated dishes were randomly selected under microscope. The resistance of patch electrode was 3-4 MΩ when filled with intracellular solution (ICS) containing (in mM): 130 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 MgATP, with pH 7.3 and osmolarity ∼315 mOsm. After whole-cell configuration, the recorded cell was voltage-clamped at -60 mV, and glutamate (100 μM) was focally applied to the cell by means of computer-controlled multi-barrel perfusion system (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA). The electrical signal was acquired via the Digidata 1322 acquisition system and saved in a computer using pCLAMP program (Axon Instruments) for off-line analysis using Clampfit program (Axon Instruments).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Sigmaplot software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). All data were examined using Student's t-tests and presented as mean ± standard error of mean. The statistical significance was considered at the p < 0.05.

Results

Confirmation of increased expression of TGF-β1 in the neocortex and hippocampus of TGF-β1 transgenic mice

It was previously reported that both the transgenically-expressed porcine TGF-β1 mRNA and the endogenousely expressed TGF-β1 mRNA are increased in the brain of TGF-β1 mice [18]. To confirm the PCR genotyping results, we performed Western blot assays of the hippocampal and neocortical homogenates of TGF-β1 mice and WT littermates using rabbit anti-porcine TGF -β1. The blotting results demonstrated the pres ence of the porcine TGF-β1 protein in the hippocampus and neocortex of TGF-β1 mice, whereas virtually no porcine TGF-β1 protein was detected in the tissues of the WT littermates (Figures 1A and 1B, n = 7 paired samples from 7 TGF-β1 mice and 7 WT littermates, respectively). The detected immunoblotting band was approximately 45 kDa, which represents the unprocessed form of porcine TGF-β1 [18]. Notably, regional disparities between the hippocampal and neocortical expression of TGF-β1 were observed in the TGF-β1 mice used in this study. Specifically, the porcine TGF-β1 protein density in the hippocampus was approximately 2.5 times greater than that of the cortical extract (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Expression of TGF-β1 in brains of T64 transgenic mice. A. Representative blot of immunoblotting assays of porcine TGF-β1 in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from wild-type (WT) and TGF-β1 mice (T64). In this figure and all other figures, WTh = WT hippocampus; T64h = T64 hippocampus; WTc = WT neocortex; T64c = T64 neocortex. B. Summary of the normalized density of porcine TGF-β1 blots (WTh: 0.00; T64h: 1.4989±0.1187; WTc:0.00; T64c: 0.5415±0.1298; n = 7 blots of tissues from 7 animals in each group).

Increased TGF-β1 leads to activation of glial cells

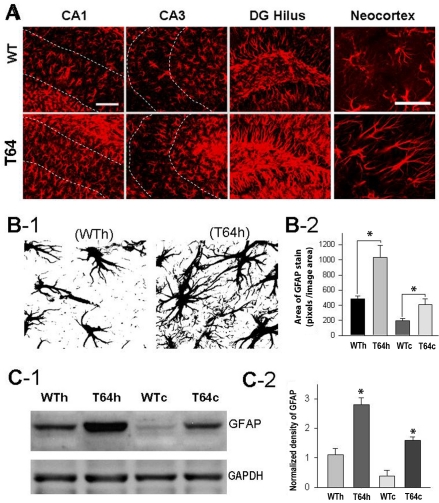

Astrocytes and microglia constitute the major populations of glial cells in the CNS. TGF-β1 mice display a characteristic pattern of perivascular astrocytosis [18]. TGF-β1 regulates the expression of GFAP [23]. GFAP is an intermediate filament found specifically in astrocytes, and its accumulation indicates astrocyte activation. To study the profiles of astrocytosis in the neocortex and hippocampus, we made immunohistochemical assays of brain sections from TGF-β1 mice (n = 3) and WT littermates (n = 3) using antibodies against GFAP. Consistent with a previous report [18], our assays revealed that astrocytic overexpression of TGF-β1 in the T64 mice led to astrocytosis, as indicated by an increase in the immunoreactivities of GFAP in the hippocampus and neocortex (Figure 2A). Our imaging analysis showed that in comparison to the WT controls, the GFAP-immunopositive cells in TGF-β1 mice were ramified, forming more spreading branches (Figure 2B-1), thus displaying larger GFAP staining areas within unitary image fields (Figure 2B-2). Our data also revealed that in both the WT and TGF-β1 mouse brains, more GFAP-immunopositive astrocytes were found in the hippocampus than in the neocortex (not shown), as indicated by approximately 2.5 times more GFAP immunoreactivity in the hippocampus than in the neocortex (Figure 2B-2). Consistent with the image analysis, our Western blot assays also demonstrated a significant increase of GFAP in the hippocampus and neocortex of TGF-β1 mice in comparison to the WT controls, displaying 2.5 times larger amount of GFAP in hippocampal tissues than in neocortical tissues (Figures 2C-1 and 2C-2).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of TGF-β1 leads to astrocytosis in the neocortex and hippocampus. A. Representative images of GFAP staining in sub-regions CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus and the neocortex of WT and TGF-β1 (T64) mice. Scale bar = 100 μm (CA1, CA3, and DG Hilus) and 50 μm (Neocortex), respectively. B-1. Converted black and white images were used for the measurement of the area of GFAP-stains using Image-J. Note the increase of fine neurites in astrocytes in TGF-β1 mice. B-2. Showing are the areas (pixels) of GFAP stains in the hippocampus of WT and TGF-β1 mice (WTh: 483±39, T64h:1033±162, n = 6 images in each group, *P<0.05; WTc: 194±32; T64c: 413±69, n = 6 images in each group, *P<0.05). C-1. Representative blots of immunoblotting assays of GFAP in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice. C-2. Normalized density of immunoblot of GFAP (WTh: 1.15±0.23, T64h:2.78±0.22, n = 3 blots of tissues from 3 mice in each group, *P<0.05; WTc: 0.37±0.22; T64c: 1.57±0.13, n = 3 blots of tissues from 3 mice in each group, *P<0.05).

In addition to astrocytosis, aged TGF-β1 mice (≥12-month-old) display microgliosis [9], suggesting that increased TGF-β1 causes an activation of microglia. To examine whether microglial cells are also activated in the hippocampus and neocortex of young mice in response to chronically increased TGF-β1, we performed immuno-histochemistry of brain sections prepared from WT and TGF-β1 mice that were approximately 2-month-old. We stained for cluster of differentiation molecule 11b (CD11b, also known as Mac-1), which is a cell surface antigen restricted to microglia (or infiltrated macrophages) in the brain. Increased CD11b is a hallmark of microglia activation [24,25]. Immunohistochemical staining identified more CD11b-immunopositive microglia in the hippocampus and neocortex of TGF-β1 mice than that in WT mice (Figure 3A). Notably, when compared with the WT controls, microglia in the hippocampus and neocortex of TGF-β1 mice exhibited bulky cell body (Figure 3A, right panel) that was associated with more and thicker branch processes (Figure 3B-1), resulting in larger staining areas of CD11b within unitary image fields (Figure 3B-2). These findings suggest that chronic increase of TGF-β1 induces microglial activation in the brain of young mice.

Figure 3.

Excessive TGF-β1 induces microgliosis in the neocortex and hippocampus. A. Representative of confocal microscopic images of immunostained CD11b in subregions CA1, CA3 and DG of the hippocampus and the neocortex of WT and TGF-β1 (T64) mice. Scale bar = 100 μm (CA1, CA3, and DG Hilus) and 50 μm (Neocortex), respectively. B-1. Converted black and white images were used for measuring the area of CD11b-stains. Note the increase of branches with microglia in TGF-β1 mice. B-2. Plotting data show the areas of CD11b stains in the hippocampus of WT and TGF-β1 mice (WTh: 203±24, T64h:431±51, n = 6 images in each group, *P<0.05; WTc: 121±12; T64c: 241±19, n = 6 images in each group, *P<0.05).

Increased TGF-β1 upregulates the expression of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the hippocampus and neocortex

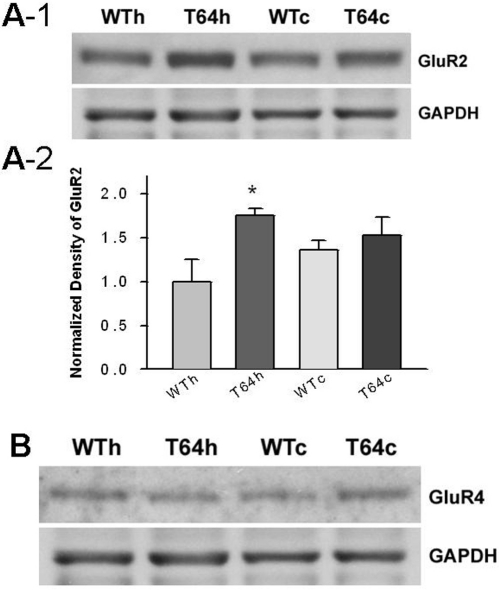

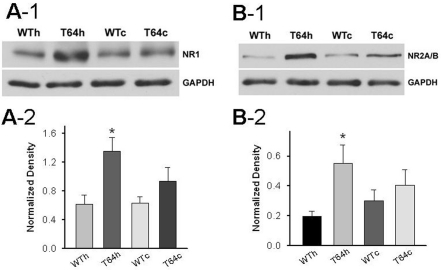

To investigate whether chronic overexpression of TGF-β1 affects glutamatergic synapses in the hippocampus and neocortex, we measured the expression levels of GluR2, GluR4, NR1 and NR2A/B subunits by Western blot assays. We examined these iGluR subunits because GluR2 as well as NR1 and NR2A/B subunits are the predominant subunits of synaptic AMPARs and NMDARs, respectively [26,27]. Although GluR4 is generally lower throughout the CNS, it is highly expressed in the hippocampus at the early developmental stage. Our Western blot assays revealed that when compared with the WT littermate controls, protein level of AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit, but not GluR4 subunit, was increased in the hippocampus of TGF-β1 mice (Figure 4). In addition, the NMDA receptor NR1 and NR2A/B subunits were also significantly upregulated in the hippocampus of TGF-β1 mice (Figure 5).We also observed that when compared with the WT controls, the expression of these tested iGluR subunits in the neocortex of TGF-β1 mice showed a trend of increase but was not significant.

Figure 4.

Chronic increase of TGF-β1 augments AMPA receptor subunit expression. A-1. Example blots of GluR2 in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice. A-2. Summary of the normalized density of immunoblot of GluR2 in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice (WTh: 1.0±0.5, T64h:1.74±0.21, n = 4 blots of tissues from 4 mice in each group, *P<0.05; WTc: 1.35±0.13; T64c: 1.50±0.14, n = 4 blots of tissues from 4 mice in each group, P<0.05). B. Example blots of GluR4 in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice.

Figure 5.

Chronic increase of TGF-β1 enhances NMDA receptor subunit expression. A-1. Example blots of NR1 subunit in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice. A-2. Summary of the normalized density of immunoblot of NR1 in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice (WTh: 0.6±0.15, T64h:1.35±0.25, n = 3 blots of tissues from 3 mice in each group, *P<0.05; WTc: 0.61±0.12; T64c: 0.94±0.25, n = 3 blots of tissues from 3 mice in each group). B-1. Example blots of NR2A/B subunit in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice. B-2. Summary of the normalized density of immunoblot of NR2A/B in hippocampal and neocortical tissues from WT and TGF-β1 mice (WTh: 0.19±0.04, T64h: 0.55±0.12, n = 5 blots of tissues from 5 mice in each group, *P<0.05; WTc: 0.3±0.08; T64c: 0.4±0.11, n = 5 blots of tissues from 5 mice in each group).

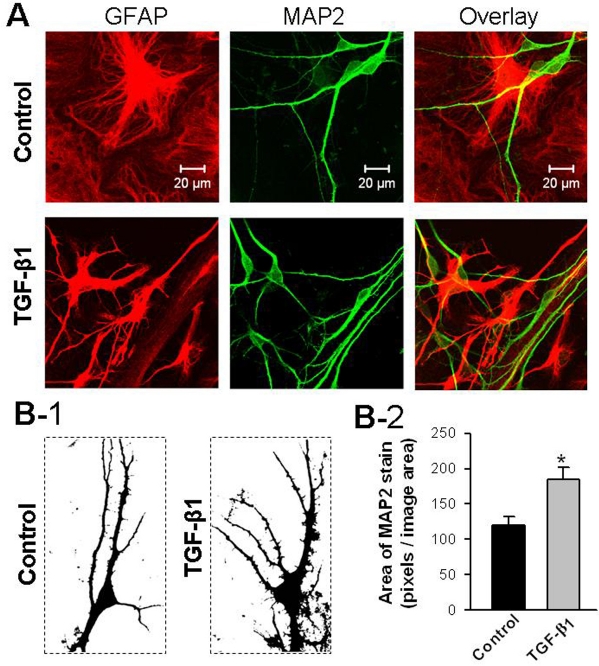

TGF-β1 produces changes in morphology of cultured hippocampal astrocytes and pyramidal neurons

To examine whether gliosis and increased expression of iGluRs in hippocampal neurons of TGF-β1 mice directly result from chronic exposure to increased TGF-β1, we treated primary cultures of astrocytes and neurons isolated from the hippocampus of rat fetus with TGF-β1. The treatment was administered beginning on the first day in culture for 7–11 days, and the effect of TGF-β1 on the morphology of the cultured astrocytes and neurons was examined using immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy. By counting the cells, we found that TGF-β1 treatment did not affect the proliferation of astrocytes (not shown) but changed the morphology of astrocytes. Specifically, the TGF-β1 treated astrocytes displayed higher immunoreactivity to GFAP when compared with the controls, and they were ramified with more outgrowing branches (Figure 6A, right panel). In addition, TGF-β1 treatment increased the neurite outgrowth of pyramidal neurons. The increased neurites were immunopositive against micro-tubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), a neuron-specific cytoskeletal protein that is rich in dendrites (Figure 6A, middle panel). Moreover, the dendrites of TGF-β1 treated neurons were associated with more spine-like extrusions (Figure 6B-1). Consequently, TGF-β1 treatment increased the immunostaining area of MAP2 with unitary image field (Figure 6B-2). Taken together, our results indicate that chronic exposure of hippocampal astrocytes and neurons to TGF-β1 alters their morphology.

Figure 6.

Treatment of cultured hippocampal neurons with TGF-β1 increases neurite outgrowth. A. Example confocal microscopic images of cultured hippocampal cells that were double-stained for GFAP and MAP2, cellular markers for astrocytes and neurons, respectively. B-1. The black and white images of MAP2 staining illustrate the morphology of control neurons (left) and TGF- β1 treated neurons (right). Note the increase of neurites in TGF-β1 treated cultures. B-2. Plot summarizes the stained areas of MAP2 in control and TGF-β1 treated hippocampal neuron on the 7th DIV (Control: 120±13, TGF-β1:185±16, n = 6 images in each group, *P<0.05).

TGF-β1 enhances glutamatergic activity in cultured hippocampal neurons

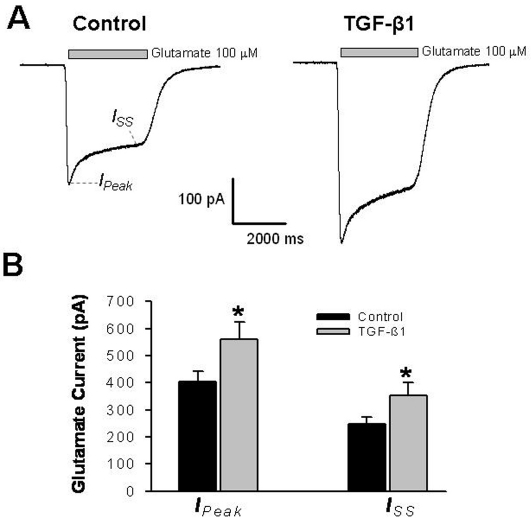

We found that the expression of some iGluR subunits was increased in the hippocampus of TGF-β1 mice. To ascertain the direct effect of TGF-β1 on glutamatergic transmission in hippocampal neurons, we used whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings to measure glutamate-evoked currents in cultured hippocampal neurons treated with or without TGF-β1. Our study revealed that TGF-β1 treatment significantly increased glutamate-evoked transmembrane current (n = 17 neurons in the control and the TGF-β1 treated group, respectively) (Figures 7A and 7B). This finding further indicates that TGF-β1 can directly regulate hippocampal glutamatergic activities.

Figure 7.

Treatment of cultured hippocampal neurons with TGF-β1 enhances glutamate-evoked current. A. Representative traces of glutamateevoked current in cultured WT rat hippocampal neurons (DIV11-12) that were treated with or without (control) TGF-β1. B. Plotted is the summary of glutamate-evoked peak current (IPeak) and steady state current (ISS) recorded from control and TGF-β1 treated neurons (IPeak: control = 408±36 pA, TGF-β1 = 565±66 pA, n = 17, *P<0.05; ISS: control = 250±26 pA, TGF-β1 = 353±50 pA, n = 17, *P<0.05).

Discussion

The expression of TGF-β1 is upregulated in the brain following chronic injuries [28]. This increased expression of TGF-β1 is often accompanied by gliosis and alterations in glutamatergic functions [29,30]. Thus, TGF-β1 mice serve as a useful tool to study the role of TGF-β1 in the regulation of glutamatergic transmission. In the current study, we demonstrated that astrocytosis and microgliosis occur in the TGF-β1 mice at young ages. More importantly, we found that chronically increased TGF-β1 enhances the expression of key iGluR subunits in hippocampal neurons.

Chronically increased TGF-β1 causes gliosis in the brain

Gliosis, including astrocytosis and microgliosis, is one of the major constituents of inflammatory responses in the CNS [3,9]. Astrocytes respond to injuries and/or inflammatory signals with morphological changes as well as increased expression of various structural molecules such as GFAP and secretary cytokines including TGF-β1 [18]. Microglia are macrophage-like immune cells residing in the CNS. In response to injuries and/or inflammatory signals, microglia participate in the processes of antigen presentation, phagocytosis and production of cytokines [3], contributing to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases [31]. A previous study reported that aged TGF-β1 mice (>12-month-old) display astrocytosis with most prominence around cerebral blood vessels [18]. Consistent with this previous report, we found astrocytosis and microgliosis in the same strain of transgenic mice at young ages, suggesting that gliosis is not dependent on age but it is a reaction to chronically increased production of TGF-β1. Our study also found that there are more astrocytes in the hippocampus than in the neocortex of WT mouse brains, and overexpression of TGF-β1 proportionally increased the expression of GFAP in the hippocampus and neocortex, respectively (Figures 2B and 2C). The larger GFAP stained area may indicate a larger population of astrocytes in the hippocampus. Perhaps, this may explain the higher increase of porcine TGF-β1 (Figure 1) and stronger inflammatory reaction in the hippocampus, as indicated by robust microgliosis in this brain region (Figure 3B).

While overproduction of TGF-β1 induces inflammatory responses including widespread gliosis in the brain of aged mice [19,20], TGF-β1 deficiency also elicits extensive microgliosis and infiltration of immune cells, causing increased apoptotic neurons with reduced synaptic integrity in the neocortex [2]. Interestingly, TGF-β1 stimulates microglia-mediated clearance of amyloid-β peptide [21] and inhibits microglial activity, thereby minimizing inflammation in the brain [32,33]. Together, these data suggest that alteration in TGF-β1 expression in the brain is closely related to glial cell activation, and such changes in the homeostatic balance of TGF-β1 expression leads to inflammatory responses in the brain.

TGF-β1 overexpression alters the hippocampal expression of AMPA and NMDA receptor sub-units

Previous studies indicated that altered TGF-β1 expression occurs under neurodegenerative conditions, which are often associated with structural and functional changes in glutamatergic synapses. On a related note, it is well known that glial cells, astrocytes in particular, modulate glutamatergic synaptic functions by controlling glutamate-glutamine cycle [34]. In addition, glia-derived proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α [13,14] and IL-1β [15], regulate the expression and localization of iGluRs in hippocampal neurons.

In the present study, we found that chronically increasing TGF-β1 production significantly enhances the expression of some iGluR subunits in the hippocampus (Figures 4 and 5), thus demonstrating a critical role of TGF-β1 in the regulation of glutamatergic synaptic functions. Our immunoblot assays displayed a slight but insignificant increase of iGluR subunits in the neocortex of TGF-β1 mice. This minor increase of iGluR subunits in the neocortex of the TGF-β1 mice may be due to the lower expression level of TGF-β1 in this brain region (Figure 1).

At glutamatergic synapses, AMPA and NMDA receptors are the major subtypes of iGluRs that mediate fast excitatory transmission [35,36]. Both receptors have specific expression profiles across the brain, with differences in regional distribution and subunit composition [37,38]. In the adult hippocampus, AMPA receptors predominantly consist of GluR1-GluR2 or GluR2-GluR3 subunits [39,40], whereas most NMDA receptor complexes contain two NR1 and two NR2 subunits [41]. In contrast, GluR4 is highly expressed in the hippocampus only in the early developmental stage [42]. We found that in the young adult TGF-β1 mice, the major iGluR sub-units GluR2, NR1 and NR2A/B, but not GluR4, are significantly increased in the hippocampus, suggesting that TGF-β1 regulates iGluR expression in a subunit-specific manner.

Astrocytes control the extracellular concentration of glutamate in the brain by up-taking and releasing glutamate [43,44]. Interestingly, TGF-β1 has been shown to increase glutamate concentration by inhibiting astrocytic clearance of glutamate [45]. Considering that glutamate released from astrocytes modulates iGluRs in hippocampal synapses [44], it is plausible that TGF -β1-induced astrocytosis contributes to the regulation of iGluR functions. Given that hippocampal astrocytes express AMPARs [46], the increased expression of GluR2 subunits in the hippocampus of TGF-β1 mice might also be associated with increased expression in astrocytes. TGF-β1 receptors are abundantly expressed in the neurons [47] and glial cells [8], and the activation of TGF-β1 signalling produces long-term effects on synaptic transmission [48,49]. Since glial cells serve as the major sources of TGF-β1 in the cortex and hippocampus [7], the increased expression of iGluR sub-units in hippocampal neurons of TGF-β1 mice could be a direct consequence of enhanced TGF -β1 activity on neurons or a consequence of indirect activation of glial cells. Our findings showed that treating cultured hippocampal neu rons with TGF-β1 enhanced glutamate receptor-mediated currents (Figure 7), further suggesting that TGF-β1 can directly regulate the activity of iGluRs in neurons.

The present study revealed a significant increase of NR1 and NR2 subunit expression in the hippocampus of TGF-β1 mice. It is important to note that excessive glutamate and/or overexpressed NMDA receptors result in excitotoxicity [50]. For example, over-activation of NMDA receptors triggers a gratuitous entry of Ca2+, which in turn activates proteolytic enzymes such as calpains, which degrade essential proteins [51]. The increased intracellular Ca2+ enhances the mitochondrial electron transport and the production of reactive oxygen species, consequently inducing neuronal apoptosis [52]. Therefore, the enhanced expression of NMDA receptor subunits in TGF-β1 mice may explain, at least partially, the influence of increased TGF-β1 in the process of neurodegeneration [20].

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by a research grant from Canadian Institute of Health Research (MOP 84517) to W.-Y. L.; an Early Researcher award from the Ontario Ministry for Research and Innovation to P.W.F., and an award from National Council of Science and Technology (Mexico) CONACyT to A. M-C. The authors thank Dr. Tony Wyss-Coray for providing T64 transgenic mice for the study.

References

- 1.Krieglstein K, Strelau J, Schober A, Sullivan A, Unsicker K. TGF-beta and the regulation of neuron survival and death. J Physiol Paris. 2002;96(1-2):25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(01)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brionne TC, Tesseur I, Masliah E, Wyss-Coray T. Loss of TGF-beta 1 leads to increased neuronal cell death and microgliosis in mouse brain. Neuron. 2003;40(6):1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K. The transforming growth factor-betas: structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and functions. J Neurochem. 2000;75(6):2227–2240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegenthaler JA, Miller MW. Transforming growth factor beta1 modulates cell migration in rat cortex: effects of ethanol. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(7):791–802. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes FC, Sousa VO, Romao L. Emerging roles for TGF-beta1 in nervous system development. IntJ Dev Neurosci. 2005;23(5):413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesne S, Blanchet S, Docagne F, Liot G, Plawin-ski L, MacKenzie ET, Auffray C, Buisson A, Pietu G, Vivien D. Transforming growth factor-beta1-modulated cerebral gene expression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(9):1114–1123. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finch CE, Laping NJ, Morgan TE, Nichols NR, Pasinetti GM. TGF-beta 1 is an organizer of responses to neurodegeneration. J Cell Biochem. 1993;53(4):314–322. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240530408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flanders KC, Ren RF, Lippa CF. Transforming growth factor-betas in neurodegenerative disease. ProgNeurobiol. 1998;54(1):71–85. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckwalter MS, Wyss-Coray T. Modelling neuroinflammatory phenotypes in vivo. J Neuro-inflammation. 2004;1(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau CG, Zukin RS. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(6):413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Zukin RS, Bennett MV, Cho S, Pulsinelli WA. Switch in glutamate receptor subunit gene expression in CA1 sub-field of hippocampus following global ischemia in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(21):10499–10503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwak S, Weiss JH. Calcium-permeable AMPA channels in neurodegenerative disease and ischemia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16(3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beattie EC, Stellwagen D, Morishita W, Bresnahan JC, Ha BK, von Zastrow M, Beattie MS, Malenka RC. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFalpha. Science. 2002;295(5563):2282–2285. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440(7087):1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai AY, Swayze RD, El-Husseini A, Song C. Interleukin-1 beta modulates AMPA receptor expression and phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;175(1-2):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Docagne F, Nicole O, Gabriel C, Fernandez-Monreal M, Lesne S, Ali C, Plawinski L, Carmeliet P, MacKenzie ET, Buisson A, Vivien D. Smad3-dependent induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in astrocytes mediates neuroprotective activity of transforming growth factor-beta 1 against NMDA-induced necrosis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21(4):634–644. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buisson A, Lesne S, Docagne F, Ali C, Nicole O, MacKenzie ET, Vivien D. Transforming growth factor-beta and ischemic brain injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23(4-5):539–550. doi: 10.1023/A:1025072013107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyss-Coray T, Feng L, Masliah E, Ruppe MD, Lee HS, Toggas SM, Rockenstein EM, Mucke L. Increased central nervous system production of extracellular matrix components and development of hydrocephalus in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor-beta 1. Am J Pathol. 1995;147(1):53–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyss-Coray T, Borrow P, Brooker MJ, Mucke L. Astroglial overproduction of TGF-beta 1 enhances inflammatory central nervous system disease in transgenic mice. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;77(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyss-Coray T, Masliah E, Mallory M, McConlogue L, Johnson-Wood K, Lin C, Mucke L. Amyloidogenic role of cytokine TGF-beta1 in transgenic mice and in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1997;389(6651):603–606. doi: 10.1038/39321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyss-Coray T, Lin C, Yan F, Yu GQ, Rohde M, McConlogue L, Masliah E, Mucke L. TGF-beta1 promotes microglial amyloid-beta clearance and reduces plaque burden in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):612–618. doi: 10.1038/87945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong H, Xiang YY, Farchi N, Ju W, Wu Y, Chen L, Wang Y, Hochner B, Yang B, Soreq H, Lu WY. Excessive expression of acetylcholinesterase impairs glutamatergic synaptogenesis in hippo-campal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(41):8950–8960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2106-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reilly JF, Maher PA, Kumari VG. Regulation of astrocyte GFAP expression by TGF-beta1 and FGF-2. Glia. 1998;22(2):202–210. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199802)22:2<202::aid-glia11>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakselman S, Bechade C, Roumier A, Bernard D, Triller A, Bessis A. Developmental neu-ronal death in hippocampus requires the microglial CD11b integrin and DAP12 immunoreceptor. J Neurosci. 2008;28(32):8138–8143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1006-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotshenker S. The role of Galectin-3/MAC-2 in the activation of the innate-immune function of phagocytosis in microglia in injury and disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2009;39(1-2):99–103. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isaac JT, Ashby M, McBain CJ. The role of the GluR2 subunit in AMPA receptor function and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54(6):859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephenson FA. Subunit characterization of NMDA receptors. Curr Drug Targets. 2001;2(3):233–239. doi: 10.2174/1389450013348461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith GM, Hale JH. Macrophage/Microglia regulation of astrocytic tenascsynergistic action of transforming growth factor-beta and basic fibroblast growth factor. J Neurosci. 1997;17(24):9624–9633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09624.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Platt SR. The role of glutamate in central nervous system health and disease–a review. Vet J. 2007;173(2):278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brareview of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130(4S Suppl):1007S–1015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiala M, Cribbs DH, Rosenthal M, Bernard G. Phagocytosis of amyloid-beta and inflammation: two faces of innate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11(4):457–463. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boche D, Cunningham C, Gauldie J, Perry VH. Transforming growth factor-beta 1-mediated neuroprotection against excitotoxic injury in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(10):1174–1182. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000090080.64176.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boche D, Cunningham C, Docagne F, Scott H, Perry VH. TGFbeta1 regulates the inflammatory response during chronic neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22(3):638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmada M, Centelles JJ. Excitatory amino acid neurotransmission. Pathways for metabolism, storage and reuptake of glutamate in brain. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d701–d718. doi: 10.2741/a314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groc L, Bard L, Choquet D. Surface trafficking of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: physiological and pathological perspectives. Neurosci-ence. 2009;158(1):4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molnar E, Pickard L, Duckworth JK. Developmental changes in ionotropic glutamate receptors: lessons from hippocampal synapses. Neuroscientist. 2002;8(2):143–153. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernard V, Bolam JP. Subcellular and sub-synaptic distribution of the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor in the neostriatum and globus pallidus of the rat: co-localization at synapses with the GluR2/3 subunit of the AMPA receptor. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(12):3721–3736. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nusser Z. AMPA and NMDA receptors: similarities and differences in their synaptic distribution. CurrOpin Neurobiol. 2000;10(3):337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geiger JR, Melcher T, Koh DS, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH, Jonas P, Monyer H. Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron. 1995;15(1):193–204. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sans N, Vissel B, Petralia RS, Wang YX, Chang K, Royle GA, Wang CY, O'Gorman S, Heinemann SF, Wenthold RJ. Aberrant formation of glutamate receptor complexes in hippocampal neurons of mice lacking the GluR2 AMPA receptor subunit. J Neurosci. 2003;23(28):9367–9373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09367.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozawa S, Kamiya H, Tsuzuki K. Glutamate receptors in the mammalian central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54(5):581–618. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomes AR, Correia SS, Esteban JA, Duarte CB, Carvalho AL. PKC anchoring to GluR4 AMPA receptor subunit modulates PKC-driven receptor phosphorylation and surface expression. Traffic. 2007;8(3):259–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenna MC. The glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric: fates of glutamate in brain. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(15):3347–3358. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evanko DS, Zhang Q, Zorec R, Haydon PG. Defining pathways of loss and secretion of chemical messengers from astrocytes. Glia. 2004;47(3):233–240. doi: 10.1002/glia.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown DR. Dependence of neurones on astrocytes in a coculture system renders neurones sensitive to transforming growth factor beta1-induced glutamate toxicity. J Neurochem. 1999;72(3):943–953. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seifert G, Steinhauser C. Ionotropic glutamate receptors in astrocytes. Prog Brain Res. 2001;132:287–299. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(01)32083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konig HG, Kogel D, Rami A, Prehn JH. TGF-{β}1 activates two distinct type I receptors in neurons: implications for neuronal NF-{κ}B signaling. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(7):1077–1086. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chin J, Angers A, Cleary LJ, Eskin A, Byrne JH. TGF-beta1 in Aplysia: role in long-term changes in the excitability of sensory neurons and distribution of TbetaR-II-like immunoreactivity. Learn Mem. 1999;6(3):317–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang F, Endo S, Cleary LJ, Eskin A, Byrne JH. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in long-term synaptic facilitation in Aplysia. Science. 1997;275(5304):1318–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mishra OP, Fritz KI, ivoria-Papadopoulos M. NMDA receptor and neonatal hypoxic brain injury. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7(4):249–253. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardingham GE. Coupling of the NMDA receptor to neuroprotective and neurodestructive events. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 6):1147–1160. doi: 10.1042/BST0371147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schulz JB, Matthews RT, Klockgether T, Dichgans J, Beal MF. The role of mitochon-drial dysfunction and neuronal nitric oxide in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;174(1-2):193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]