Abstract

This study was designed to investigate the protective effect of the heart-protecting musk pill (HMP) on inflammatory injury of kidney from spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR). Male SHRs aged 4 weeks were divided into SHR model group, HMP low-dosage group (13.5 mg/kg), and HMP high-dosage group (40 mg/kg). Age-matched Wistar–Kyoto rats were used as normal control. All rats were killed at 12 weeks of age. Tail-cuff method and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were used to determine rat systolic blood pressure and angiotensin II (Ang II) contents, respectively. Renal inflammatory damage was evaluated by the following parameters: protein expressions of inflammatory cytokines, carbonyl protein contents, nitrite concentration, infiltration of monocytes/macrophages in interstitium and glomeruli, kidney pathological changes, and excretion rate of urinary protein. HMP did not prevent the development of hypertension in SHR. However, this Chinese medicinal compound decreased renal Ang II content. Consistent with the change of renal Ang II, all the parameters of renal inflammatory injury were significantly decreased by HMP. This study indicates that HMP is a potent suppressor of renal inflammatory damage in SHR, which may serve as a basis for the advanced preventive and therapeutic investigation of HMP in hypertensive nephropathy.

Keywords: spontaneously hypertensive rat, inflammation, musk pill, nephropathy

Introduction

The kidney can be both a target of and a contributor to hypertension. Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) have been widely used as a primary hypertension animal model, and multiple renal structural and functional alterations mark the feature of hypertensive nephropathy. It has been revealed that a complex pathological network involving angiotensin II (Ang II), monocytes/macrophages, inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress is an important participant in triggering renal injury of SHR.1–3 Thus, we hypothesize that anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategy may manage hypertensive target organ damage, and previous studies of our research center has indicated anti-inflammation mechanism may serve as a base for the protective effects of atorvastatin in hypertensive nephropathy.4

Heart-protecting musk pill (HMP) is a traditional Chinese medicinal compound, which has been effectively used for treating coronary heart disease (CHD) with angina pectoris.5 Recently, there has been a new wave of interest in the HMP due to its protecting effect on multiple organ injuries. HMP improves renal function and blood pressure when combined with other hypotensive agents in hypertensive patients.6 Post-treatment with HMP decreases myocardial fibrosis in SHR without interfering with systolic blood pressure (SBP).7 Furthermore, HMP reduces arterial inflammation markers of C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and D-dimer levels in coronary syndrome subjects.8 Little is known, however, about the mechanisms underlying these multiple organ protective effects of HMP.

The present study was designed to explore the effect of HMP on renal inflammatory parameters, pathological morphology and functional changes in SHR. With this study, we expect to clarify the protective mechanisms and potential clinical benefits of HMP on hypertensive nephropathy.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

The animal procedures were in accordance with the Animal Use and Care Guidelines of the Experimental Animal Center of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Male SHR (aged 4 weeks) and Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rats (aged 4 weeks) were purchased from Shanghai Experimental Animal Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences. All the rats were housed in a temperature-controlled room regulated on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water.

Materials

HMP were purchased from Shanghai Hutchison Pharmaceuticals (Shanghai, China). An instrument for noninvasive blood pressure determination was purchased from Shanghai Alcott Biotech (Shanghai, China). Commercially available Ang II, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, and microalbuminuria (MA), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were obtained from BioDev Tech (Beijing, China). JD801 analysis system for pathological image was purchased from Jiangsu Jieda Biotech (Jiangsu, China). Primary antibodies of inductible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (sc-8310), intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (sc-1511), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (sc-146), and β-actin (sc-47778) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA). A computerized gel imaging analysis system was obtained from Shanghai Tannon (Shanghai, China). A radio immunoassay kit of β2-microglobulin (β2-MG) was purchased from Beijing North Institute Biotech (Beijing, China). Multifunctional microplate reader Spectra Max 190 was obtained from Molecular Devices (Carlsbad, CA). All chemicals were of analytical grade.

Experimental groups and treatment

SHR were divided into three experimental groups: SHR model group (n = 9), HMP low dosage group (13.5 mg/kg, n = 9), and HMP high dosage group (40 mg/kg, n = 9). HMP powder was dissolved in purified water (HMP low dosage, 1.35 mg/mL; HMP high dosage, 4.0 mg/mL), and daily administrated through intragastric gavage (10 mL/kg). Drinking water (10 mL/kg) was used for the SHR model group. The treatments were carried out through week 4 to week 12 of the age of SHR. In the whole experimental process WKY rats (n = 9) were used as the age-matched control of SHR, and drinking water (10 mL/kg) was used for sham treatment.

Sample preparation

Pelltobarbitalum natricum (40 mg/kg) was used for the anesthesia of rats. Twenty-four hour urine samples were collected on the day before rats were killed by cervical dislocation. Urine samples were lower-speed centrifuged, and supernatants were separated and stored at −20°C until assayed for urinary concentrations of total protein, MA, and β2-MG.

Blood samples were obtained at 12 weeks of age through cardiac puncture and collected in centrifuge tubes that contained 50 μL EDTA (0.30 mol/L), 25 μL dimercaprol (0.32 mol/L) and 50 μL 8-hydroxyquinoline sulfate (0.34 mol/L). Plasma was separated and stored at −20°C for further assays.

Kidneys were immediately removed after sacrifice of the rats. One kidney was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis, and another kidney was frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein assays and preparation of renal tissue homogenates.

SBP measurement

SBP was measured weekly by using tail-cuff method. The cuff was inflated until the pulse waveform disappeared; values at the disappearance of the waveform was recorded as the systolic pressure.

Plasma and kidney Ang II determination

Ang II concentration was detected using ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Examination of renal inflammatory injury

ICAM-1, iNOS, and TGF-β1 protein expression was analyzed by Western-blot. For total protein extraction, about 200 mg kidney tissues were homogenized in cell lysis buffer (pH 7.4) containing proteinase inhibitors and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 4 g. Concentration of total protein was determined by Lowry assay. A total of 50 μg protein was separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and then incubated with primary antibodies (1:200) overnight and second antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 1 hour. The determination was performed with enhanced chemiluminescene by exposure to X-Omat BT Films (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Kidney protein level of MCP-1 was determined using commercially available ELISA kit. Carbonyl protein formation was determined by 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) method.9 The results were calculated using the extinction coefficient of 22,000 for aliphatic hydrazone and demonstrated by nmol/mg protein.

Griess reaction was used for the detection of renal tissue nitrite (NO2−) concentration. Test solutions (100 μL) were added to 96-well flat-bottomed plates containing 100 μL/well of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphtylethylenediamine dihydrochloride, and 5% phosphoric acid). After 10 minutes at room temperature the absorbance of each well was measured at 540 nm, and the NO2− concentration was determined from a sodium nitrite standard curve.

Infiltration of monocytes/macrophages was examined by immunochemistry using CD68 antibody. Images of immunochemistry were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Fifteen consecutive microscopic fields were examined for each kidney section, and CD68-positive cells (brown) were counted in interstitium and glomeruli.

With the use of HE and periodic acid silver metheramine (PASM) stained kidney sections, pathological morphologic changes were evaluated by using a semi-quantitative histological score (score 0–3; normal to severe) for glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and arteriolar hyalinosis (maximal score = 12) as described previously.10

Renal function was evaluated by urinary excretion rates of total protein, β2-MG, and MA. Urinary concentration of total protein was measured by Coomassie Brilliant Blue method. ELISA and radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits were used for the determination of MA and β2-MG levels, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Results were analyzed by Student’s t-test, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

SBP

SHR showed a progressive increase in SBP during the whole experimental period, whereas WKY rats maintained their SBP unchanged (P > 0.05). HMP treatment failed to prevent the development of hypertension in SHR (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of HMP on SBP and Ang II levels of SHR

| Group |

SBP (mm Hg) |

Ang II |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 weeks of age | 12 weeks of age | Plasma (pg/mL) | Kidney (pg/mg tissue) | |

| WKY rats | 132.3 ± 7.45 | 138.5 ± 10.62 | 435.2 ± 154.8 | 18.09 ± 7.92 |

| SHR | 131.8 ± 5.90 | 193.3 ± 5.72a | 474.9 ± 96.9 | 30.70 ± 10.94b |

| HMP low dosage | 135.3 ± 8.90 | 194.0 ± 9.09 | 390.6 ± 130.4 | 24.44 ± 8.60c |

| HMP high dosage | 134.0 ± 8.04 | 196.8 ± 9.87 | 196.6 ± 35.9d | 21.16 ± 6.03c |

Notes: Values are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 9). Statistical significant test for comparison was done by one-way ANOVA.

P < 0.01, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.05, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.05, versus SHR;

P < 0.01, versus SHR.

Abbreviations: Ang II, angiotensin II; HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

Plasma and kidney Ang II

Plasma Ang II concentrations were similar between WKY rats and SHR at 12 weeks of age (P > 0.05). HMP low dosage treatment showed a tendency to decrease plasma Ang II levels in SHR group. However, these changes were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). HMP high dosage prevented this increase in plasma Ang II (P < 0.01). In contrast, kidney tissue levels of Ang II were significantly increased in SHR at 12 weeks of age compared with age-matched WKY rats (P < 0.05). After 8 weeks of treatment, kidney Ang II levels were markedly decreased by HMP (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

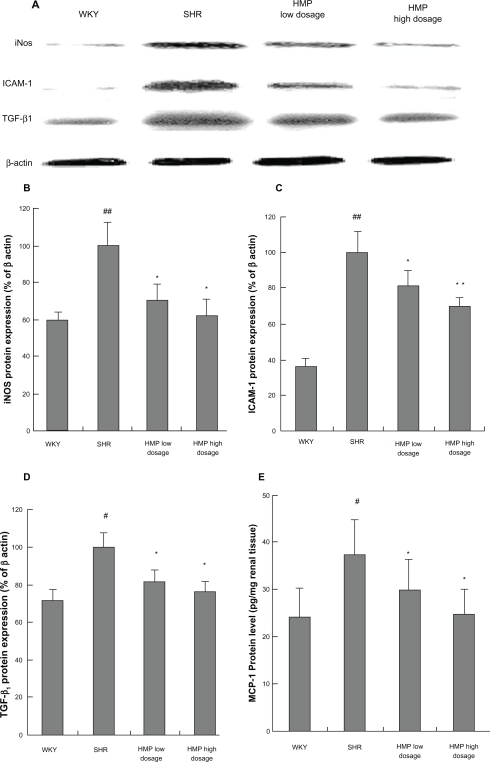

Renal protein expressions of iNOS, ICAM-1, and TGF-β1

Renal protein expressions of iNOS, ICAM-1, and TGF-β1 were significantly increased in SHR at 12 weeks of age compared with age-matched WKY rats (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). HMP treatment prevented the increased protein expressions of iNOS, ICAM-1, and TGF-β1 in SHR kidney (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Figures 1A, 1B, and 1C).

Figure 1.

Effect of HMP on protein expressions of inflammatory cytokines in SHR kidney. Total protein was extracted from kidney for Western-blot assay to determine iNOS, ICAM-1, and TGF-β1 protein expression. Optical density of bands corresponding to Western-blot were read by gel imaging analysis system, and optical density of each band was expressed as the percentage relative to the corresponding β-actin band (%). Renal tissue homogenates and ELISA kits were used for the examination of MCP-1 protein level. Data of MCP-1 protein level were calculated from the standard curve plotted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A) Bands corresponding to Western-blot. B) Bar graph of iNOS. C) Bar graph of ICAM-1. D) Bar graph of TGF-β1. E) Bar graph of MCP-1. Renal tissue homogenates and ELISA kits were used for the examination of MCP-1 protein level.

Notes: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus WKY rats (SHR only); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus SHR, n ≥ 3 (Westein-blot) or n = 9 (ELISA).

Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; iNOS, inductible nitric oxide synthase; MCP, monocyte chemotactic protein; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; TGF, transforming growth factor; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

Renal protein levels of MCP-1

Renal protein levels of MCP-1 were significantly increased in SHR at 12 weeks of age (37.40 ± 7.48 pg/mg renal tissue) compared with age-matched WKY rats (24.05 ± 6.28 pg/mg renal tissue) (P < 0.05). HMP decreased renal protein levels of MCP-1 in SHR significantly after 8 weeks of treatment (29.73 ± 7.32 pg/mg renal tissue for HMP low dosage group; 25.77 ± 4.96 pg/mg renal tissue for HMP high dosage group) (P < 0.05) (Figure 1D).

Renal carbonyl protein and NO2− contents

Compared with WKY rats, renal carbonyl protein and NO2− contents in SHR changed in parallel with protein expressions of inflammatory cytokines. HMP decreased contents of carbonyl protein and NO2− after 8 weeks of treatment (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of HMP on renal carbonyl protein and NO2− contents, and monocytes/macrophages infiltration of SHR

| Group | Carbonyl protein (nmol/mg protein) | NO2−(μmol/g) |

Monocytes/macrophages |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glo (count/glo) | Interstitium (count/mm2) | |||

| WKY rats | 2.81 ± 0.99 | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 10.1 ± 3.3 | 23.1 ± 4.7 |

| SHR | 5.15 ± 1.70a | 0.63 ± 0.85b | 24.5 ± 6.3a | 38.9 ± 6.2b |

| HMP low dosage | 2.43 ± 1.29c | 0.45 ± 0.06c | 13.4 ± 5.5c | 23.6 ± 3.4c |

| HMP high dosage | 1.25 ± 0.96d | 0.45 ± 0.08c | 10.8 ± 3.6d | 21.6 ± 4.2c |

Notes: Values are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). Statistical significant test for comparison was done by one-way ANOVA.

P < 0.01, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.05, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.05 versus SHR;

P < 0.01 versus SHR.

Abbreviations: Glo, glomeruli; HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rats; NO2−, nitrite; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

Infiltration of monocytes/macrophages

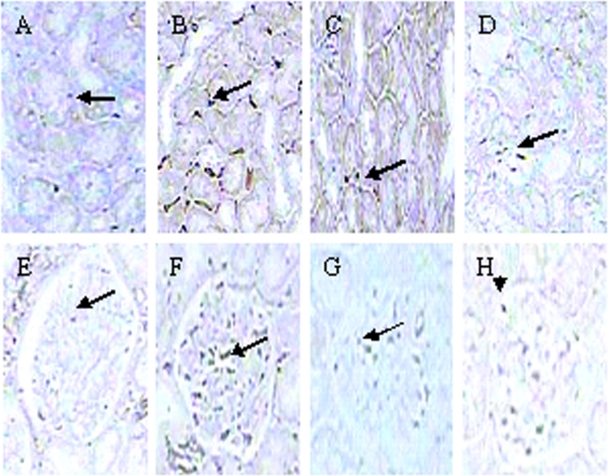

Numbers of monocytes/macrophages in interstitium and glomeruli were significantly increased in SHR at 12 weeks of age compared with age-matched WKY rats (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, respectively). HMP inhibited the renal cortical infiltration of monocytes/macrophages in SHR (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of HMP on monocytes/macrophages stained positively with CD68 antibody in SHR interstitial (A–D) and glomerular (E–H). Immunochemistry staining, original magnification × 400). A and E refer to WKY rats; B and F refer to SHR; C and G refer to HMP low dosage group; D and H refer to HMP high dosage group.

Abbreviations: HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

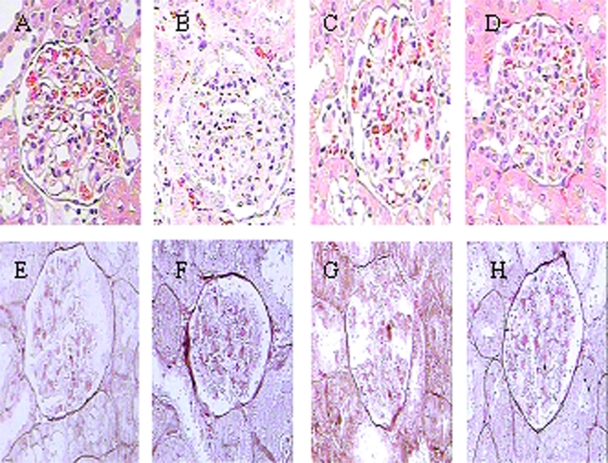

Renal pathological parameters

Pathological scores of glomeruli, tubule-interstitum, and renal vascular lesions were significantly increased in SHR at 12 weeks of age compared with age-matched WKY rats (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). After 8 weeks of treatment, HMP significantly decreased the pathological scores of glomeruli, tubule-interstitum, and renal vascular lesions in SHR (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Figure 3; Table 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of HMP on renal pathological parameters with the use of HE (A–D) and PASM (E–H) stained kidney sections in SHR. A and E refer to WKY rats; B and F refer to SHR; C and G refer to HMP low dosage group; D and H refer to HMP high dosage group.

Abbreviations: HE, hematoxylin-erosin; HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; PASM, periodic acid silver metheramine; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

Table 3.

Effect of HMP on renal pathological parameters in SHR kidney

| Group |

Pathological scores |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomeruli | Tubule-interstitium | Vascular | Total | |

| WKY rats | 1.08 ± 0.49 | 1.58 ± 0.66 | 1.08 ± 0.38 | 3.57 ± 1.03 |

| SHR | 5.17 ± 1.66a | 5.25 ± 1.83b | 3.50 ± 1.05a | 13.9 ± 4.30b |

| HMP low dosage | 2.42 ± 1.24c | 3.17 ± 1.03c | 1.92 ± 1.07c | 7.50 ± 1.87c |

| HMP high dosage | 1.83 ± 0.82d | 2.58 ± 1.11c | 1.83 ± 0.82d | 6.25 ± 1.63c |

Notes: Values are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). Statistical significant test for comparison was done by one-way ANOVA.

P < 0.01, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.05, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.05, versus SHR;

P < 0.01, versus SHR.

Abbreviations: HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

Urinary excretions of total protein, MA, and β2-MG

Urinary excretions of total protein, MA, and β2-MG were significantly increased in SHR at 12 weeks of age compared with age-matched WKY rats (P < 0.01). After 8 weeks of HMP treatment, urinary excretions of total protein, MA, and β2-MG were markedly decreased (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of HMP on urinary excretions of total protein, MA, and β2-MG of SHR

| Group | Total protein (mg/day) | MA (μg/mL) | β2-MG (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WKY rats | 7.88 ± 1.69 | 15.75 ± 5.48 | 17.63 ± 2.74 |

| SHR | 14.91 ± 3.18a | 72.12 ± 17.58a | 43.13 ± 8.20a |

| HMP low dosage | 9.50 ± 1.87b | 50.46 ± 13.86c | 25.67 ± 9.75c |

| HMP high dosage | 9.02 ± 1.40b | 29.55 ± 10.45b | 25.79 ± 12.01c |

Notes: Values are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 8). Statistical significant test for comparison was done by one-way ANOVA.

P < 0.01, versus WKY rats (SHR only);

P < 0.01, versus SHR;

P < 0.05, versus SHR.

Abbreviations: HMP, heart-protecting musk pill; MA, microalbuminuria; β2-MG, β2-microglobulin; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar Kyoto.

Discussion

The pathological changes due to chronic inflammation are evidential in hypertensive renal disease. Interstitial fibrosis, proteinuria, and decreased creatinine clearance rate manifest severe renal disorders of SHR. Our previous studies indicated the up-regulated inflammatory cytokines expression was present in SHR kidney, and the protective effects of atorvastatin in hypertensive nephropathy might be related to its anti-inflammation mechanism.2–4 A role of inflammatory reaction in hypertensive nephropathy is further suggested by the study of nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitor, which prevented the development of hypertension and renal injury.11 To add more evidence, chronic treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor delayed the onset of renal dysfunction characterized by increased total protein and albumin excretion of SHR.12 In the present study, we have evaluated the effect of HMP on inflammation-related kidney damage in SHR to appeal our proposed concept that inflammation serves as primary target of therapeutic strategy in end-organ damage of hypertension. Our choosing of HMP is due to the following considerations: 1) HMP is not an anti-hypertensive drug, 2) HMP exerts cardiovascular effect through anti-inflammatory mechanisms, and 3) HMP is the top-selling prescription medicine in China and available immediately for therapeutic use.

It is widely accepted that elevated BP positively correlates to hypertensive target organ damage, including renal injury. However, it has been reported that atorvastatin reduced proteinuria and decreased CRP and IL-6 in renal damage patients of hypertension without interfering with BP.13 In contrast, hydrochlorothiazide (HRH) treatment failed to prevent the increase of renal injury in SHR, even though HRH effectively blocked the development of hypertension.14 These studies suggested that, under certain conditions, BP elevation and renal injury might stand for two independent pathological procedures. In this study we observed that HMP treatment failed to prevent the development of hypertension in SHR. On the other side, our data here are especially aimed to define the optimal treatment of hypertensive nephropathy through an anti-inflammation pathway.

Previous studies indicated a complex causative network involving Ang II and inflammatory cytokines in triggering renal damage in hypertension such as increasing mesangial cell proliferation, contracting afferent and efferent glomerular arteriole, and decreasing glomerular filtration rate.15 Also, it has been reported that Ang II stimulated the synthesis of type I and type IV collagen and fibronectin,16 thus increasing the extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. On the other side, olmesartan, an Ang II type-1 (AT1) receptor blocker, decreased proteinuria, renal immune cells infiltration and morphology alterations in SHR by inhibition of kidney levels of Ang II.17 In this study, we observed the similar result that HMP inhibited levels of Ang II which implied a key role of Ang II in regulation of chronic inflammation in hypertension.

Inflammatory cytokines have been crucially involved in the pathogenesis of hypertensive renal damage. Our current study focused on the effect of HMP on iNOS, ICAM-1, TGF-β1, and MCP-1 protein expressions in SHR kidney. The production of pathological higher concentration of nitric oxide (NO) by iNOS has been considered as a pro-inflammatory mediator and implicated in several cardiovascular diseases.18 Inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide can induce the expression of iNOS in monocytes/macrophages, neutrophil granulocytes, and many other cell types. The overproduced NO will react with superoxide anion to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which can react with tyrosine residue to form nitrotyrosin and cause tissue injury, including renal damage.9 In the current study, renal tissue NO2− concentration evaluated as the consequence of over expressed iNOS was inhibited by HMP treatment. Upregulation of ICAM-1 in tubular epithelial cells observed in kidney diseases with inflammation actively participated in the progress of fibrosis in glomeruli and tubule interstitum.19 This study indicated that the ICMA-1 expression was significantly inhibited by HMP and suggested an action mechanism of HMP in preserving renal function and reducing interstitial fibrosis. TGF-β1 plays a key role in promoting the overproduction of ECM and thus participates in renal structural and functional alterations.20 MCP-1 exhibits a chemotactic activity toward monocytes/macrophages and induces the production of inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IFN-γ, which have been shown to mediate pathological adhesion, migration, and phagocytosis of inflammatory cells.21,22 In addition, macrophages stimulate renal interstitial fibrosis via the production of matrix protein from renal interstitium and intercapillary cells.23 Thus, an agent that reduces monocytes/macrophages infiltration may be beneficial to hypertension-related renal fibrosis. In the present study, HMP decreased renal iNOS, ICAM-1, TGF-β1, and MCP-1 protein expressions, as well as interstitial and glomerular infiltration of monocytes/macrophages, which implied the protective role of HMP in hypertensive nephropathy.

Inflammation is closely related to oxidative stress. The overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) participate cellular and tissue damage through oxidative modification of protein, lipids, carbohydrate, and DNA.24 ROS can initiate local inflammation and tissue fibrosis by the activation of NF-κB and TGF-β signaling pathways, respectively.25,26 In this study, protein carbonyl content was evaluated as the parameter of oxidative stress. Our data showed that HMP decreased carbonyl protein levels in SHR kidney, which suggested an antioxidative mechanism might underlie the preventive and therapeutic effect of HMP on hypertensive renal injury.

Previous studies have detected renal pathological changes in SHR at 14 weeks of age, including: 1) accumulation of mesangial matrix and thickening and focal sclerosis of capillary basement membrane; 2) cloudy swelling and irregular basement membrane thickening of renal tubules; and 3) interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration, accumulation of ECM and fibrosis.14 In this study we got a similar result that the pathological scores of glomeruli, tubule interstitum, and renal vascular lesions were significantly increased in SHR at the age of 12 weeks. The reducing effect of HMP on pathological scores of SHR kidney strongly demonstrated the efficacy of anti-inflammation therapy on hypertensive renal injury.

Hypertensive nephropathy marks with increased excretion of urinary protein, which is mostly attributed to increased permeability of glomerular filtration membrane, damage of electrostatic barrier, and renal tubular reabsorption. Urinary excretions of albumin and β2-MG are sensitive to early functional damage of glomerular filtration and renal tubular reabsorption, respectively. Albumin is a macromolecule carrying negative electric charges. Therefore, a small amount of albumin will penetrate through the glomerular electrostatic barrier under normal conditions. The urinary albumin concentration will be obviously increased even if there is a mild injury of electrostatic barrier.27,28 β2-MG can penetrate through the glomerular electrostatic barrier, and 99.9% of β2-MG will be reabsorbed by the proximal renal tubule. When the function of renal tubular reabsorption is damaged, urinary β2-MG concentration will be increased.28 The improvement of renal function (measured by urinary excretions of total protein, MA, and β2-MG) by HMP further prove our concept of anti-inflammatory therapy for hypertensive target organ damage.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that HMP inhibited inflammatory status of the hypertensive kidney which was associated with a marked improvement of kidney function in SHR. It is worth noting that the protective effect of HMP on hypertensive renal diseases is not related to the change of blood pressure. We propose the anti-inflammatory mechanism may serve the base for the therapeutic investigation of HMP in hypertensive nephropathy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this research. This study was supported by grants from State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2009ZX09311-003) and Science of Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 05JC14056).

References

- 1.Blasi ER, Rocha R, Rudolph AE, Blomme EA, Polly ML, McMahon EG. Aldosterone/salt induces renal inflammation and fibrosis in hypertensive rats. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1791–1800. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun L, Gao YH, Tian DK, et al. Inflammation of different tissues in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Acta Physiologica Sinica. 2006;58(4):318–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun L, Ke Y, Zhu CY, et al. Inflammatory reaction versus endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors expression, re-exploring secondary organ complications of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Chinese Med J. 2008;121(22):2305–2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian DK, Hu SY, Ling S, et al. Hypertensive nephropathy treatment by atovastatin-a study of anti-inflammation therapy for target organ damage of hypertension. Acta Biophysica Sinica. 2010;26(4):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.He BL, Guo H, Yang GB, Chen YX. Clinical observation of Shexiangbaoxin pills in treating 72 cases of coronary. Chin Mod Med. 2009;16(14):66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu SJ, Fang Q, Gu JX. Clinical observation of preventive and therapeutic effects of Heart-protecting Musk Pill on hypertensive nephropathy. Chin Trad Patent Med. 2004;26(12):52–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu DJ, Hong HS, Jiang Q. Effect of Shexiang Baoxin Pill in alleviating myocardial fibrosis in spontaneous hypertensive rats. CJITWM. 2005;25(4):350–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong YD, Wu H, Zhao P, et al. Effects of Shexiang Baoxin Pill on carotid atheromatous plaque. CJITWM. 2006;26(9):780–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bian K, Gao Z, Weisbrodt N, Murad F. The nature of heme/iron induced protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(10):5712–5717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katafuchi R, Kiyoshi Y, Oh Y, et al. Glomerular score as a prognosticator in IgA nephropathy: its usefulness and limitation. Clin Nephrol. 1998;49(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Ferrebuz A, Vanegas V, Quiroz Y, Mezzano S, Vaziri ND. Early and sustained inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB prevents hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(1):51–57. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenhard SC, Nerurkar SS, Schaeffer TR, et al. P38 MAPK inhibitors ameliorate target organ damage in hypertension: Part 2. Improved renal function as assessed by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307(3):939–946. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng W, Zhou SH, Zhang M, Li XP. The effect of atorvastatin on proteinuria and plasma CRP and IL-6 in patients with hypertensive nephropathy. Chin J Hypertension. 2005;13(4):767–770. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, Nishiyama A. Enhanced intrarenal angiotensinogen contributes to early renal injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2073–2080. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skrbic R, Igic R. Seven decades of angiotensin (1939–2009) Peptides. 2009;30(10):1945–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma R, Sharma M, Reddy S, Savin VJ, Nagaria AM, Wiegmann TB. Chronically increased intrarenal angiotensin II causes nephropathy in an animal model of type 2 diabetes. Front Biosci. 2006;11:968–976. doi: 10.2741/1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koike H, Sada T, Mizuno M. In vitro and in vivo pharmacology of olmesartan medoxomil, an angiotensin II type AT1 receptor antagonist. Hypertens Suppl. 2001;19(1):S3–S14. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200106001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bian K, Davis K, Kuret J, Binder L, Murad F. Nitrotyrosine formation with endotoxin-induced kidney injury detected by immunohistochemistry. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(1 Pt 2):F33–F40. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.1.F33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrizabalaga P, Solé M, Abellana R, et al. Tubular and interstitial expression of ICAM-1 as a marker of renal injury in IgA nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23(3):121–128. doi: 10.1159/000068920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuchida K, Zhu Y, Siva S, Dunn SR, Sharma K. Role of Smad4 on TGF-beta-induced extracellular matrix stimulation in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2003;63(6):2000–2009. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Errante PR, Frazão JB, Condino-Neto A. The use of interferon-gamma therapy in chronic granulomatous disease. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2008;3(3):225–230. doi: 10.2174/157489108786242378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salem ML, Hossain MS, Nomoto K. Mediation of the immunomodulatory effect of beta-estradiol on inflammatory responses by inhibition of recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells and their gene expression of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2000;121(3):235–245. doi: 10.1159/000024323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishida M, Hamaoka K. Macrophage phenotype and renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2008;110(1):31–36. doi: 10.1159/000151561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakim FA, Pflueger A. Role of oxidative stress in diabetic kidney disease. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16(2):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islam MS, Yoshida H, Matsuki N, et al. Antioxidant, free radical-scavenging, and NF-kappaB-inhibitory activities of phytosteryl ferulates: structure-activity studies. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;111(4):328–337. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09146fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Z, Seo JY, Ha H, et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate TGF-beta1-induced plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 upregulation in mesangial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309(4):961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guy M, Newall R, Borzomato J, Kalra PA, Price C. Diagnostic accuracy of the urinary albumin: creatinine ratio determined by the CLINITEK Microalbumin and DCA 2000+ for the rule-out of albuminuria in chronic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;399(2):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang J, Li Q, Yin N, et al. Relationship between transferrin and β2-microglobulin and microalbminuria in patients with hypertension. Progress Modern Biomed. 2008;8(7):1299–1301. [Google Scholar]