Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To determine medication use and adherence among community-dwelling patients with heart failure (HF).

PATIENTS AND METHODS: Residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, with HF were recruited from October 10, 2007, through February 25, 2009. Pharmacy records were obtained for the 6 months after enrollment. Medication adherence was measured by the proportion of days covered (PDC). A PDC of less than 80% was classified as poor adherence. Factors associated with medication adherence were investigated.

RESULTS: Among the 209 study patients with HF, 123 (59%) were male, and the mean ± SD age was 73.7±13.5 years. The median (interquartile range) number of unique medications filled during the 6-month study period was 11 (8-17). Patients with a documented medication allergy were excluded from eligibility for medication use within that medication class. Most patients received conventional HF therapy: 70% (147/209) were treated with β-blockers and 75% (149/200) with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers. Most patients (62%; 127/205) also took statins. After exclusion of patients with missing dosage information, the proportion of those with poor adherence was 19% (27/140), 19% (28/144), and 13% (16/121) for β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, and statins, respectively. Self-reported data indicated that those with poor adherence experienced more cost-related medication issues. For example, those who adhered poorly to statin therapy more frequently reported stopping a prescription because of cost than those with good adherence (46% vs 6%; P<.001), skipping doses to save money (23% vs 3%; P=.03), and not filling a new prescription because of cost (46% vs 6%; P<.001).

CONCLUSION: Community-dwelling patients with HF take a large number of medications. Medication adherence was suboptimal in many patients, often because of cost.

Community-dwelling patients with heart failure take a substantial number of medications; the authors of this study of 209 patients found that medication adherence is suboptimal, primarily because of the cost of treatment.

ACC = American College of Cardiology; ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blocker; EF = ejection fraction; HF = heart failure; PDC = proportion of days covered

More than 5 million Americans are living with heart failure (HF), a chronic disease associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.1 The use of evidence-based medications is a cornerstone of HF treatment because these medications have been shown to decrease symptoms, reduce hospitalizations, slow cardiac remodeling, and improve survival.2 In patients with reduced ejection fraction (EF), medication adherence has been shown to decrease hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and health care costs.3 Furthermore, objectively measured medication adherence has been reported to predict event-free survival, regardless of EF.4

However, estimates of medication adherence among patients with HF are vague, ranging from 10% to 94% depending on how adherence is assessed and the population being studied.3-10 Further, previous studies have frequently identified patients with HF using administrative data alone, an approach known to have poor validity in some settings.11 In addition, the methodology used to assess medication adherence may be unreliable because use of prescription claims data to assess adherence may miss prescriptions that are not charged to the insurance provider, and self-reported adherence assessments have shown poor correlation with electronic-based adherence.12 Finally, community studies on medication adherence in patients with HF are lacking and require further investigation.

For editorial comment, see page 268

To address these gaps in knowledge, we aimed to prospectively evaluate medication use and adherence among a community-based HF cohort. We used pharmacy records to objectively examine medication use and adherence among patients with HF and identify factors potentially associated with adherence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This is a population-based study conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, the estimated 2008 population of which was 141,360. Most residents are white (89%), and approximately 50% are female.13 This type of study is possible in this county because of the small number of medical providers, including Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center, and a few private practitioners. The records from each institution are indexed through the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a centralized data system that allows retrieval of medical data from the population.14

Patient Identification

Details of a clinical visit are transcribed and appear in the electronic medical record within 24 hours. Patients with potential HF were identified using natural language processing of the electronic medical record.15 Nurse abstractors then examined the possible cases to verify HF diagnosis on the basis of the Framingham criteria and to collect clinical data.16 Patients were prospectively recruited into the study. Study patients were required to complete questionnaires and to undergo an echocardiographic study and venipuncture. Hospitalized patients were contacted during hospitalization and outpatients at their next clinic appointment. Written authorization for study participation was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

At enrollment, patients provided optional authorization to obtain pharmacy records from all pharmacies where they refilled medications within the past 2 years. Patients were excluded from analysis if they did not provide authorization to contact their pharmacies, all pharmacy records could not be obtained, they were nursing home residents, or they did not speak English.

Medication Adherence

Adherence was measured objectively on the basis of pharmacy records. Pharmacy data were obtained for the 6-month period after study enrollment. Each pharmacy was contacted to obtain medication refill histories for study patients. Medication data obtained from all pharmacies for each patient were combined in a single dataset for analysis. Medications were considered unique by medication name. Medication use refers to having a prescription filled at the pharmacy. Medications were divided by pharmaceutical class of action, such as β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and statins. Patients were excluded from eligibility for medication use and adherence for a class of medications if they had an allergy or intolerance documented in the medical record and were not using an alternative medication within that class in the study period. Patients with missing dosage information were excluded from the medication adherence analysis. Medication adherence was calculated by medication class for patients filling a prescription within that class by the proportion of days covered (PDC).17 The PDC is calculated as the number of the days in the measurement period covered by prescription claims for the same medication or another in its therapeutic class. Poor adherence was defined as a PDC less than 80%, a level commonly used.18,19 Sensitivity analyses were conducted using a PDC less than 88%, a level shown to be associated with event-free survival in HF.20 Medications examined included those commonly prescribed in the treatment of patients with HF, including β-blockers, ACEIs/ARBs, statins, digoxin, spironolactone, nitrates, and loop diuretics. Antidepressant use was also examined.

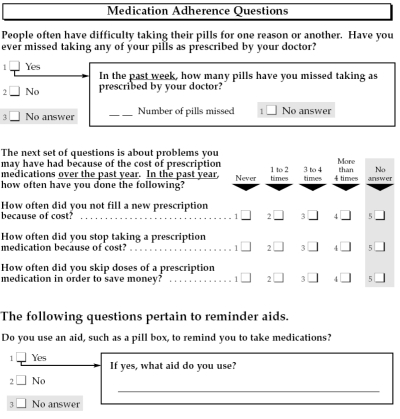

Factors previously shown to be associated with medication adherence were collected.21-23 Age, sex, educational level, marital status, previous depression diagnosis, and New York Heart Association class were abstracted from the medical record. The total number of medications was calculated from the pharmacy data. Questionnaires, which were administered by a registered nurse during a face-to-face outpatient interview conducted within 6 weeks of consent, included questions on global medication adherence (eg, whether patients had ever missed a medication; how often they had missed a medication within the past week; for full questionnaire, see Figure 1).24 Three questions were asked about the effect of the cost of medications: (1) “How often did you not fill a new prescription because of cost?” (2) “How often did you stop taking a prescription because of cost?” and (3) “How often did you skip doses of a prescription medication in order to save money?” Patients were also asked “Do you use an aid, such as a pillbox, to remind you to take medications?” and “If yes, what aid do you use?”

FIGURE 1.

Questionnaire administered to study patients.

Patient Baseline Characteristics

Nurse abstractors collected baseline characteristics from the medical record. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm Hg, or use of an antihypertensive medication.25 Hyperlipidemia was defined by the criteria set forth in the National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines26 or use of hyperlipidemia agents, and diabetes was defined by the American Diabetes Association criteria.27 Smoking status was defined as current or former/never on the basis of documentation. Body mass index (calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was calculated using the most recent height and weight at the time of consent. A physician's diagnosis was used to document a history of atrial fibrillation, depression, and cerebrovascular disease. Laboratory data collected included creatinine and brain-type natriuretic peptide levels measured closest to HF diagnosis. Creatinine clearance was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation.28 Brain-type natriuretic peptide was measured by a 2-site immunoenzymatic sandwich assay on the DxI 800 automated immunoassay system (Beckman Instruments, Chaska, MN) in the Immunochemical Core Laboratory of Mayo Clinic.

Echocardiography

The Mayo Clinic Echocardiographic Laboratory performed echocardiography and evaluated the findings using M-mode, quantitative, and semiquantitative methods to measure left ventricular EF according to the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.29 Reduced EF was defined as less than 50%; preserved EF, as 50% or greater.30

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics are reported as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and as mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables and median (interquartile range) for continuous variables with a skewed distribution. Differences in the proportion of patients filling a medication from each medication class by EF (<50% vs ≥50%) were analyzed using the χ2 test, whereas differences in medication adherence (PDC) by EF were analyzed using a 2-sample t test. Using pharmacy-based adherence, we stratified patients into those with good (PDC, ≥80%) and poor (PDC, <80%) adherence. Differences in factors associated with medication nonadherence were analyzed between those with good and poor adherence for each medication class, using the χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and a 2-sample t test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The level of significance for all analyses was set at P<.05.

RESULTS

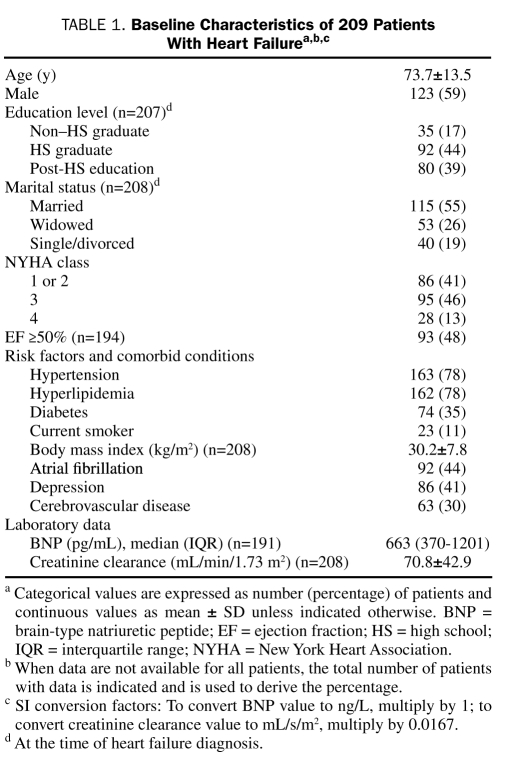

Between October 10, 2007, and February 25, 2009, 402 patients with HF were approached for enrollment, and 245 (61%) consented to the pharmacy portion of the study. We could not obtain all pharmacy records for 25 patients, 8 were nursing home residents, and 3 did not speak English, resulting in a final study population of 209. The population was older, with a mean ± SD age of 73.7±13.5 years; 123 (59%) were male, 93 (48%) had a preserved EF, and comorbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes were common (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 209 Patients With Heart Failurea,b,c

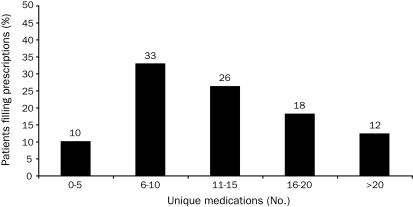

Medication Use

The number of unique medications (including all prescription medications) filled per patient during the 6-month study period is shown in Figure 2. The median number of medications filled was 11 (interquartile range, 8-17), and 26 patients (12%) filled more than 20 medications. Of the 201 patients with complete dosing information, 74 patients (37%) took at least 1 medication 4 times daily, 36 (18%) at least 3 times daily, 73 (36%) twice daily, and 18 (9%) once daily.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of patients filling prescriptions, categorized by the number of unique medications.

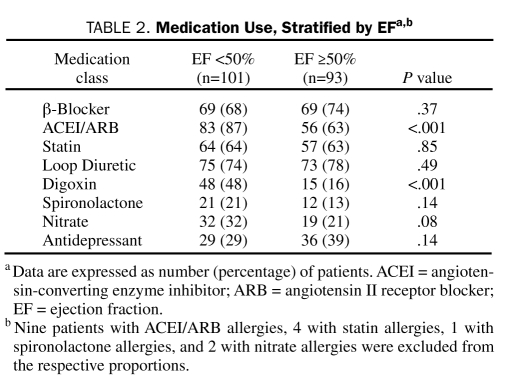

The proportion of patients taking β-blockers (70%; 147/209), ACEIs/ARBs (75%; 149/200), statins (62%; 127/205) and loop diuretics (77%; 160/209) was high. Among the 147 patients taking a β-blocker, medication use was as follows: metoprolol, 121 patients (82%); atenolol, 26 (18%); carvedilol, 19 (13%); and labetalol, 1 (0.7%) (some patients were prescribed more than one β-blocker during the study period). Patients with a reduced EF were more likely to be taking an ACEI or ARB (87% vs 63%; P<.001) and digoxin (48% vs 16%; P<.001) than patients with a preserved EF (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Medication Use, Stratified by EFa,b

Medication Adherence

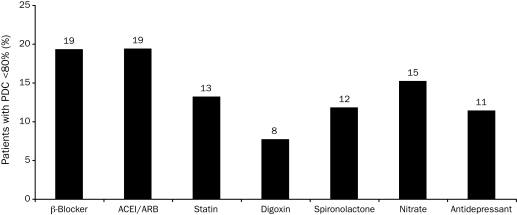

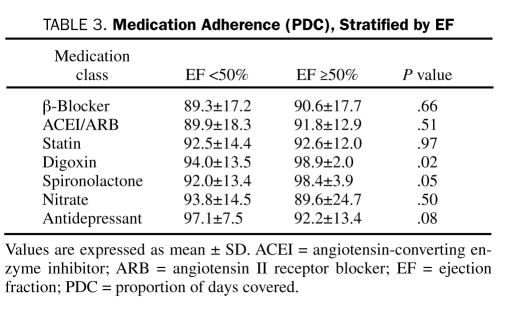

Pharmacy-Based Medication Adherence. The proportion of patients with HF who had poor adherence (PDC, <80%) to β-blockers, ACEIs/ARBs, and statins was 19% (27/140), 19% (28/144), and 13% (16/121), respectively (Figure 3). Medication adherence was not evaluated for loop diuretics because of frequent dosing changes. Patients with a reduced EF had poorer adherence to digoxin than those with a preserved EF (P=.02; Table 3). No significant differences in other medication adherence by EF were noted.

FIGURE 3.

Pharmacy-based medication adherence. The proportion of patients with poor medication adherence (PDC <80%) for each medication class are shown. Adherence was not calculated for loop diuretics because of frequent dosing changes. ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blocker; PDC = proportion of days covered.

TABLE 3.

Medication Adherence (PDC), Stratified by EF

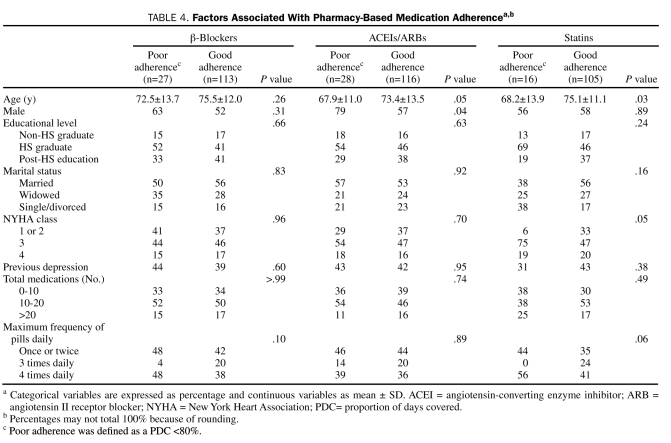

Factors associated with medication adherence for the most commonly prescribed medication classes are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Patients with poor adherence to ACEIs/ARBs and statins were younger than those with good adherence (P=.05 and P=.03, respectively; Table 4). Men had lower ACEI/ARB adherence than women (P=.04); however, sex was not associated with adherence to other medications. New York Heart Association functional class demonstrated a statistically significant association with statin adherence (P=.05), but no clear adherence pattern existed with increasing functional class. Other factors, including education level, marital status, previous depression diagnosis, incident vs prevalent HF at enrollment, dosing frequency of medication, and total number of medications were not associated with medication adherence. Sensitivity analyses using a PDC less than 88% to define poor adherence yielded similar findings.

TABLE 4.

Factors Associated With Pharmacy-Based Medication Adherencea,b

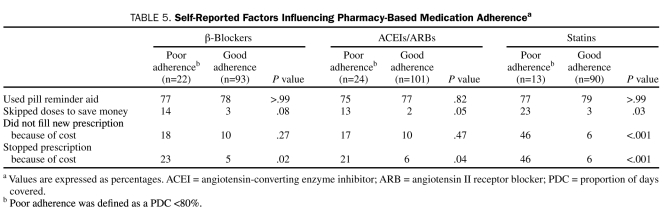

TABLE 5.

Self-Reported Factors Influencing Pharmacy-Based Medication Adherencea

Direct Questionnaire Results. Global adherence and cost-related issues were assessed by direct questionnaire. Of the enrolled study patients, 178 (85%) completed the questionnaire. Of the remaining 31 patients who enrolled in the study but did not complete the questionnaire, 4 had dementia and could not complete the questionnaires, 8 died, and 19 did not return for their visit with the nurse. Overall, 87 patients (49%) reported ever missing a pill prescribed by their physician. Among these, 57 (66%) reported missing none, 12 (14%) missed 1 pill, 6 (7%) missed 2, and 12 (14%) missed 3 or more medications within the past week.

When queried on cost-related medication issues, 18 patients (10%) reported that they had not filled a new prescription because of cost, 14 (8%) reported stopping a medication because of cost, and 8 (4%) reported skipping doses to save money. Most patients (n=134, 75%) reported using a reminder aid, 125 (93%) of whom used a medication box.

Comparison of Pharmacy-Based vs Questionnaire-Based Adherence. Patient responses to the questionnaires were compared with pharmacy-based adherence. No significant differences were found in the percentage of patients with good adherence (PDC, ≥80%) vs those with poor adherence (PDC, <80%) reporting they ever missed a medication (β-blockers: 48% vs 55%, P=.60; ACEIs/ARBs: 51% vs 54%, P=.75; and statins: 50% vs 54%, P=.80). No significant differences were found in reminder aid use on the basis of adherence status (Table 5). Patients with poor adherence were more likely to report cost-related medication issues, and differences were most striking for statin adherence. Those with poor adherence to statin therapy were more likely to report stopping a prescription because of cost than were those with good adherence (46% vs 6%; P<.001), skipping doses to save money (23% vs 3%; P=.03), and not filling a new prescription because of cost (46% vs 6%; P<.001). Those with poor adherence to β-blockers and ACEIs/ARBs were also more likely to report stopping a prescription because of cost than were those with good adherence (β-blockers: 23% vs 5%, P=.02; ACEIs/ARBs: 21% vs 6%, P=.04). Those with poor adherence to ACEIs/ARBs were also more likely to skip doses to save money (13% vs 2%; P=.05).

DISCUSSION

Community-dwelling patients with HF are commonly required to take a large number of prescription medications, and over half take at least 1 medication 3 times daily. Overall, 13% to 20% of patients with HF exhibit poor adherence to conventional HF medications. Cost is a notable barrier to adherence.

Burden of Medications

Patients with HF are prescribed a variety of guideline-based medications to optimize outcomes, as well as medications for commonly associated comorbid conditions.4 However, the burden of medications in patients with HF is largely unknown. A study of 16 patients with HF found that patients took an average of 11.1 medications daily.31 Most took medications at least twice daily, and one-quarter took medications 4 times daily. However, this study was limited by its very small sample size, and medication data were based on self-report alone. The current study substantially extends these findings by indicating that community-dwelling patients with HF with a wide range of EFs and a high comorbidity burden take a large number of medications. The median number of medications per patient during a 6-month period was 11, and more than one-third took at least 1 medication 4 times per day. Polypharmacy imposes a heavy burden on community-dwelling patients with HF.

Medication Use

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend that patients with HF who have a reduced EF take an ACEI or ARB and a β-blocker unless contraindicated because they have been shown to reduce mortality2; however, their reported use has varied in the literature. A recent study noted that 71% of patients with HF who had a reduced EF were taking an ACEI or ARB, and 37% were taking a β-blocker32; other studies have shown higher rates of β-blocker use.3,6,31 Our study showed a large proportion of patients with HF who had a reduced EF were taking a β-blocker (68%) and an ACEI or ARB (87%). Most patients receiving β-blocker therapy were taking metoprolol, a β-blocker proven to reduce mortality in patients with HF.2

Little evidence exists regarding treatments for patients with HF and preserved EF because no medications have consistently improved outcomes in clinical trials. Recommendations focus on aggressively treating comorbid conditions,2,33 which are common in patients with HF who have preserved EF.30 However, few studies have documented whether medication use differs among patients with HF who have preserved vs reduced EF. In our study, patients with a preserved EF and those with a reduced EF were taking similar medications overall; however, those with a reduced EF were more likely to be taking an ACEI or ARB and digoxin.

Medication Adherence

The measurement of medication adherence in patients with HF has been of recent interest because improved adherence has been associated with improved patient outcomes.20 Adherence in HF can be measured by patient self-report or objective methods, and so studies examining it use a variety of methodologies. Patient self-report, used in some studies,4,6,34 has been shown to have poor correlation with objective methods in some settings.12 Objective methods used include pill counts, electronic monitoring such as the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS), and prescription refill records.35 Because both pill counts and MEMS require direct patient contact, which is often not feasible, the use of prescription refill records from electronic claims data has appeared most commonly in the literature. Our study is unique in that we used pharmacy prescription refill records from multiple pharmacies instead of electronic claims data, which can miss prescriptions purchased with cash.

Studies have used various cut points to define poor adherence, ranging from patients taking less than 70% to less than 100% of a prescribed medication.34,36 We used less than 80% to define poor adherence because this cut point has been used most frequently in the literature. Because a recent study showed that use of a cut point of less than 88% to define poor adherence was associated with worse outcomes in patients with HF,20 we conducted a sensitivity analysis using this cut point. Our findings reveal that a substantial proportion of community-dwelling patients exhibit poor adherence to β-blockers (19%), ACEIs/ARBs (19%), and statins (13%) and may be at increased risk of adverse outcomes. Although other studies have shown lower adherence rates,5,9,37 these data indicate that ample opportunity exists for improvements in medication adherence among community-dwelling patients with HF.

Patients in our community cohort with poor adherence were more likely to report cost-related medication issues. Indeed, cost-related medication issues bore the most striking association with adherence, and factors such as education level, marital status, and frequency and total medication use were not significant predictors of adherence. Increasing drug copayments have been associated with decreased medication adherence in patients with HF.37 In one HF cohort, a $10 increase in ACEI copayment was associated with a 2.6% decrease in medication adherence, which correlated with an estimated 6.1% increase in hospitalizations for HF.37 Similar findings have been observed for β-blockers and statins in other populations.38 Although 77% of our patients are aged at least 65 years and are eligible for Medicare Part D, many of them reported cost-related issues. The doughnut hole coverage gap can cause substantial cost-shifting and may affect cost and medication adherence in these patients39; however, such cost-shifting is likely to be reduced in coming years with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. It is interesting to note that the most striking cost-related differences in adherence in our study were for statins. Although the out-of-pocket cost of prescription medications varies widely within a specific class on the basis of the exact medication prescribed and the insurance plan, statin adherence has been shown to vary more widely than β-blocker adherence in patients with coronary heart disease depending on the degree of insurance drug coverage.40 Our results underscore the importance of the association between cost and adherence, and discussion regarding cost is an important component of the physician-patient interaction in prescribing medications.

Limitations and Strengths

Some limitations should be acknowledged to aid in data interpretation. First, no ideal methodology exists to measure medication adherence. We relied on prescription refill data to define adherence but were unable to verify that patients were actually taking the medications they refilled. However, high concordance between prescription claims and pill counts has been demonstrated, suggesting that patients who refill their medications usually take them.41 Second, we were unable to verify whether study patients continued to use the same pharmacies for the 6 months after study enrollment. However, if additional pharmacies were used, this would have resulted in an underestimation of the number of medications and medication adherence, which were already high compared with other literature. We were unable to account for changes in directions that occurred during a refill period. We were also unable to examine over-the-counter medication use, which would be of interest in future studies. The definition of hypertension for the population included use of antihypertensive medications that may have been prescribed for HF, resulting in overestimation of the proportion of patients with hypertension. Finally, although Olmsted County is becoming increasingly diverse, most of its residents are white, and further studies are needed in communities that may differ in their racial and ethnic composition.

Our study also has several notable strengths. Our study population was unique in that patients were prospectively recruited from the community and their HF diagnosis was validated. Further, we used rigorous methodology to obtain all pharmacy records instead of relying on electronic databases and examined both objective and subjective medication adherence using pharmacy records and questionnaires, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Community-dwelling patients with HF take a substantial number of medications, often several times a day. Use of β-blockers, ACEIs or ARBs, loop diuretics, and statins was common among patients with both preserved and reduced EF. Medication adherence was suboptimal in many patients, and those with poor adherence were more likely to report cost-related medication issues. Further work is needed to determine the effect of interventions to improve medication adherence among patients with HF. Efforts to contain cost may have the largest effect on improving medication adherence and associated outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kay Traverse, RN, Annette McNallan, RN, and Amy Wagie, BS, for their study support.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1HL72435, T32 HL07111-31A1) and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (AG034676, National Institute on Aging).

An earlier version of this article appeared Online First.

REFERENCES

- 1. Writing Group Members Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee [published corrections appear in Circulation. 2010;122 (1):ell and 2009;119(3):e182] Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21-e181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Writing Committee Members. Task Force Members ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). Circulation. 2005;112(12):e154-e235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):714-725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu JR, Moser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Objectively measured, but not self-reported, medication adherence independently predicts event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14(3):203-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bagchi AD, Esposito D, Kim M, Verdier J, Bencio D. Utilization of, and adherence to, drug therapy among medicaid beneficiaries with congestive heart failure. Clin Ther. 2007;29(8):1771-1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. George J, Shalansky SJ. Predictors of refill non-adherence in patients with heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(4):488-493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T. Adherence in heart failure in the elderly: problem and possible solutions. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125(2):203-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gonzalez B, Lupon J, Parajon T, et al. Nurse evaluation of patients in a new multidisciplinary Heart Failure Unit in Spain. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;3(1):61-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. Noncompliance with congestive heart failure therapy in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(4):433-437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Artinian NT, Harden JK, Kronenberg MW, et al. Pilot study of a Web-based compliance monitoring device for patients with congestive heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32(4):226-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goff DC, Jr, Pandey DK, Chan FA, Ortiz C, Nichaman MZ. Congestive heart failure in the United States: is there more than meets the I(CD code)? The Corpus Christi Heart Project. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(1):197-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care. 2004;42(7):649-652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Census Bureau State and County QuickFacts: Olmsted County Minnesota. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/27/27109.html Accessed February 17, 2011.

- 14. Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(3):266-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pakhomov SV, Buntrock J, Chute CG. Prospective recruitment of patients with congestive heart failure using an ad-hoc binary classifier. J Biomed Inform. 2005;38(2):145-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(4)(suppl A):6A-13A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann PharmacoTher. 2006;40(7):1280-1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I, et al. Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9502):2005-2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297(2):177-186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu JR, Moser DK, De Jong MJ, et al. Defining an evidence-based cut-point for medication adherence in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157(2):285-291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu JR, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Burkhart PV. Medication adherence in patients who have heart failure: a review of the literature. Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;43(1):133-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baroletti S, Dell'Orfano H. Medication adherence in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;30;121(12):1455-1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028-3035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, Bernholz CD, Mukherjee J. Can simple clinical measurements detect patient noncompliance? Hypertension. 1980;2(6):757-764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(17):2560-2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143-3421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes–2006 [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2006;29(5):1192] Diabetes Care. 2006;29(suppl 1):S4-S42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440-1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):251-259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu JR, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Peden AR, Chen YC, Heo S. Factors influencing medication adherence in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2008;37(1):8-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calvert MJ, Shankar A, McManus RJ, Ryan R, Freemantle N. Evaluation of the management of heart failure in primary care. Fam Pract. 2009;26(2):145-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shah SJ, Gheorghiade M. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: treat now by treating comorbidities. JAMA. 2008;300(4):431-433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Evangelista LS, Berg J, Dracup K. Relationship between psychosocial variables and compliance in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):294-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther. 1999;21(6):1074-1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JM, Zhang Y, Brown JE, Marchiori G, Guyatt G. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150(5):982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cole JA, Norman H, Weatherby LB, Walker AM. Drug copayment and adherence in chronic heart failure: effect on cost and outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(8):1157-1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doshi JA, Zhu J, Lee BY, Kimmel SE, Volpp KG. Impact of a prescription copayment increase on lipid-lowering medication adherence in veterans. Circulation. 2009;119(3):390-397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Balfour DC, III, Evans S, Januska J, et al. Medicare Part D-a roundtable discussion of current issues and trends. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(1)(suppl A):3-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Federman AD, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Ayanian JZ. Supplemental insurance and use of effective cardiovascular drugs among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1732-1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grymonpre R, Cheang M, Fraser M, Metge C, Sitar DS. Validity of a prescription claims database to estimate medication adherence in older persons. Med Care. 2006;44(5):471-477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.