Abstract

Microbes within polymicrobial infections often display synergistic interactions resulting in enhanced pathogenesis; however, the molecular mechanisms governing these interactions are not well understood. Development of model systems that allow detailed mechanistic studies of polymicrobial synergy is a critical step towards a comprehensive understanding of these infections in vivo. In this study, we used a model polymicrobial infection including the opportunistic pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and the commensal Streptococcus gordonii to examine the importance of metabolite cross-feeding for establishing co-culture infections. Our results reveal that co-culture with S. gordonii enhances the pathogenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans in a murine abscess model of infection. Interestingly, the ability of A. actinomycetemcomitans to utilize L-lactate as an energy source is essential for these co-culture benefits. Surprisingly, inactivation of L-lactate catabolism had no impact on mono-culture growth in vitro and in vivo suggesting that A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate catabolism is only critical for establishing co-culture infections. These results demonstrate that metabolite cross-feeding is critical for A. actinomycetemcomitans to persist in a polymicrobial infection with S. gordonii supporting the idea that the metabolic properties of commensal bacteria alter the course of pathogenesis in polymicrobial communities.

Author Summary

Many bacterial infections are not the result of colonization and persistence of a single pathogenic microbe in an infection site but instead the result of colonization by several. Although the importance of polymicrobial interactions and pathogenesis has been noted by many prominent microbiologists including Louis Pasteur, most studies of pathogenic microbes have focused on single organism infections. One of the primary reasons for this oversight is the lack of robust model systems for studying bacterial interactions in an infection site. Here, we use a model co-culture system composed of the opportunistic oral pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and the common oral commensal Streptococcus gordonii to assess the impact of polymicrobial growth on pathogenesis. We found that the abilities of A. actinomycetemcomitans to persist and cause disease are enhanced during co-culture with S. gordonii. Remarkably, this enhanced persistence requires A. actinomycetemcomitans catabolism of L-lactate, the primary metabolite produced by S. gordonii. These data demonstrate that during co-culture growth, S. gordonii provides a carbon source for A. actinomycetemcomitans that is necessary for establishing a robust polymicrobial infection. This study also demonstrates that virulence of an opportunistic pathogen is impacted by members of the commensal flora.

Introduction

The survival of pathogens in the human body has been rigorously studied for well over a century. The ability of bacteria to colonize, persist and thrive in vivo is due to an array of capabilities including the ability to attach to host tissues, produce extracellular virulence factors, and evade the immune system. Invading pathogens must also obtain carbon and energy from an infection site, and specific carbon sources are required for several pathogens to colonize and persist in the host [1]. Although mono-culture infections provide interesting insight into pathogenesis, many bacterial infections are not simply the result of colonization with a single species, but are instead a result of colonization with several [2], [3], [4], [5]. The mammalian oral cavity is an excellent environment to study polymicrobial interactions as it is persistently colonized with diverse commensal bacteria as well as opportunistic pathogens. Our lab has utilized a two-species model system composed of the opportunistic pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and the common commensal Streptococcus gordonii to provide mechanistic insight into how specific carbon sources impact disease pathogenesis in polymicrobial infections [6], [7].

A. actinomycetemcomitans is a Gram-negative facultative anaerobic bacterium that inhabits the human oral cavity and is a proposed causative agent of localized aggressive periodontitis [8]. A. actinomycetemcomitans is found between the gums and tooth surface in the subgingival crevice [9], [10], an area restricted for O2 depending on tissue depth [11] and irrigated by a serum exudate called gingival crevicular fluid (GCF). GCF not only contains serum proteins such as complement and immunoglobulin [12], but also glucose from 10 to 500 µM in healthy patients [13] and as high as 3 mM in patients with periodontal infections [14]. L-lactate is produced by host lactate dehydrogenase in GCF [15], [16] and resident oral streptococci. Together glucose and L-lactate represent two of the small number of carbon sources that A. actinomycetemcomitans is able to catabolize [17]. A. actinomycetemcomitans has been proposed to primarily inhabit the aerobic [9] “moderate” pockets (4 to 6 mm in depth) of the gingival crevice as opposed to deeper anaerobic subgingival pockets [18].

In addition to A. actinomycetemcomitans, the subgingival crevice is home to a diverse bacterial population, including numerous oral streptococci [19], that reside in surface-associated biofilm communities [20]. Oral streptococci, aside from Streptococcus mutans, are typically non-pathogenic and depending upon the human subject and method of sampling, comprise approximately 5% [21] to over 60% [22] of the recoverable oral flora. Through fermentation of carbohydrates to L-lactate and sometimes H2O2, acetate, and CO2, oral streptococci such as S. gordonii have been shown to influence the composition of oral biofilms [19], [20], [23], [24]. Additionally, S. gordonii-produced H2O2 influences interactions between A. actinomycetemcomitans and the host by inducing production of ApiA, a factor H binding protein that inhibits complement-mediated lysis [7], [25]. Thus, streptococcal metabolites are important cues that influence the growth and population dynamics of oral biofilms and how oral bacteria interact with the host.

A. actinomycetemcomitans preferentially catabolizes L-lactate over high energy carbon sources such as glucose and fructose in multiple strains, despite the fact that this bacterium grows more slowly with L-lactate [6]. Given this preference for a presumably inferior carbon source and the observation that A. actinomycetemcomitans resides in close association with oral streptococci [26], [27], we hypothesize an in vivo benefit exists for A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate preference. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the importance of A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate catabolism during mono-culture and co-culture with S. gordonii in vitro and in a murine abscess model of infection. Our results reveal that co-culture with S. gordonii enhances colonization and pathogenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and the ability to utilize L-lactate as an energy source is essential for these co-culture benefits. Surprisingly, inactivation of L-lactate catabolism had no impact on mono-culture growth in vitro and in vivo suggesting that A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate catabolism is only critical for establishing co-culture infections. Taken together, these results provide compelling mechanistic evidence that the metabolic properties of human commensals such as S. gordonii can alter the course of pathogenesis in polymicrobial communities.

Results

A. actinomycetemcomitans metabolism of glucose and L-lactate

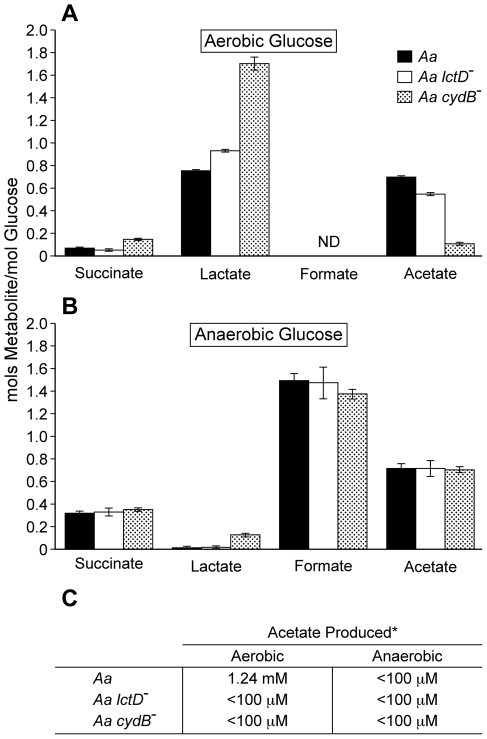

Within the gingival crevice, host-produced glucose and L-lactate are present [13], [14], [15], [16], [28] and likely serve as in vivo carbon sources for A. actinomycetemcomitans. However in contrast to glucose, L-lactate is also produced by the oral microbial flora, primarily oral streptococci [20]. Indeed, the ability of A. actinomycetemcomitans to catabolize streptococcal-produced L-lactate has been demonstrated previously [6], and it was proposed that A. actinomycetemcomitans consumes streptococcal-produced L-lactate during co-culture. To assess the importance of A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate catabolism in polymicrobial communities in vitro, we examined the metabolic profile during catabolism of L-lactate and glucose under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Aerobically, A. actinomycetemcomitans primarily produced lactate and acetate from glucose (Fig. 1A) while acetate was the sole metabolite produced by L-lactate-grown bacteria (Fig. 1C). It was intriguing that lactate was produced, but not consumed, by A. actinomycetemcomitans during aerobic catabolism of glucose. We hypothesized that the lactate produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans was likely D-lactate, which is not catabolized by A. actinomycetemcomitans [29]. Using an enzymatic assay [30], we were able to verify that >99% of the lactate produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans was indeed D-lactate.

Figure 1. Aerobic and anaerobic metabolites produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans, A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - and A. actinomycetemcomitans cydB -.

Resting cell suspensions of each culture were incubated (A )aerobically in glucose; (B), anaerobically in glucose; (C), aerobically or anaerobically in lactate. Metabolite concentrations were measured by HPLC. Data in A and B is presented as moles of metabolite produced/mole of glucose consumed. Only trace concentrations (<50 µM) of ethanol were observed in anaerobic suspensions. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 3. * Acetate concentrations are shown per mM of L-lactate consumed. The detection limit for acetate was 100 µM.

Anaerobically from glucose, A. actinomycetemcomitans primarily produced the mixed acid fermentation products formate and acetate along with lactate, succinate, and trace amounts of ethanol (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, A. actinomycetemcomitans was unable to catabolize L-lactate anaerobically (Fig. 1C), even if the potential alternative electron acceptors nitrate or dimethyl sulfoxide were added, suggesting that L-lactate oxidation was O2 dependent. This is distinct from other oral bacteria including members of the genus Veillonella [24], [31], in which L-lactate is an important anaerobic carbon and energy source. If O2 respiration was indeed required for A. actinomycetemcomitans growth with L-lactate, we hypothesized that elimination of the terminal respiratory oxidase, which is required for aerobic respiration, would abolish L-lactate utilization by A. actinomycetemcomitans aerobically. To test this hypothesis, cydB, which encodes a component of the sole putative A. actinomycetemcomitans respiratory oxidase, was insertionally inactivated. The cydB mutant was unable to catabolize L-lactate aerobically supporting the hypothesis that L-lactate oxidation requires O2 respiration (Fig. 1C). Interestingly when grown with glucose aerobically, the cydB mutant doubled much slower (6.6 hr) than the wt (1.9 hr) and cell suspensions produced a metabolite profile that differed from the wt (Fig. 1A) indicating that while not required for aerobic growth on glucose, O2 respiration is the primary means by which glucose is catabolized by wt A. actinomycetemcomitans. As expected, the cydB mutant exhibited identical growth rates anaerobically on glucose (not shown) and produced similar metabolites as the wt (Fig. 1B). Collectively, these data indicate that O2 respiration is required for L-lactate oxidation in A. actinomycetemcomitans.

As the ultimate goal of this study is to assess the importance of A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate catabolism for establishing co-culture with oral streptococci, it was important to assess whether eliminating the ability of A. actinomycetemcomitans to utilize L-lactate affected growth with glucose. To examine this, we examined growth and metabolite production in an A. actinomycetemcomitans strain in which the catabolic L-lactate dehydrogenase LctD, which is present in all strains sequenced to date [32], [33], was insertionally inactivated [29]. LctD oxidizes L-lactate to pyruvate and is required for A. actinomycetemcomitans growth with L-lactate as the sole energy source [29]. As expected, the lctD mutant was unable to catabolize L-lactate aerobically or anaerobically (Fig. 1C); however, metabolite production from glucose was not affected (Fig. 1A&B) nor was the growth rate with glucose (not shown). These data indicate that L-lactate catabolism can be eliminated in A. actinomycetemcomitans without affecting growth and metabolite production with glucose.

Utilization of L-lactate enhances co-culture growth

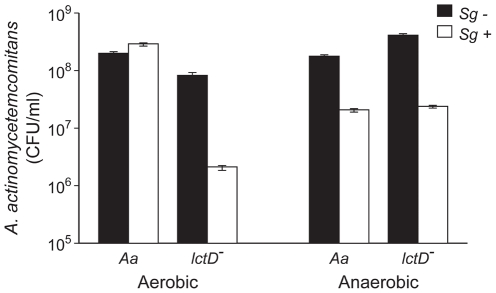

Because A. actinomycetemcomitans preferentially catabolizes L-lactate in lieu of hexose sugars [6], we hypothesized that L-lactate cross-feeding was important for establishing co-culture with oral streptococci grown on glucose. To test this hypothesis, we examined growth of glucose-grown A. actinomycetemcomitans and S. gordonii during in vitro co-culture aerobically and anaerobically. Aerobically, wt A. actinomycetemcomitans co-culture cell numbers were similar to those observed in mono-culture while the A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD mutant exhibited an approximate 25-fold decrease in cell number during co-culture with S. gordonii (Fig. 2). Anaerobically, both wt A. actinomycetemcomitans and A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - cell numbers diminished nearly 10-fold in co-culture compared to mono-culture (Fig. 2), likely due to the inability to catabolize S. gordonii-produced L-lactate.

Figure 2. Growth of A. actinomycetemcomitans, A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD -, and S. gordonii in aerobic and anaerobic co-cultures.

Strains were grown as mono- or co-cultures in 3 mM glucose aerobically or anaerobically for 10 or 12 h respectively, serially diluted and plated on selective media to determine colony forming units per ml (CFU/ml). A. actinomycetemcomitans mono-culture strains are black bars and co-culture with S. gordonii are white bars. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 3.

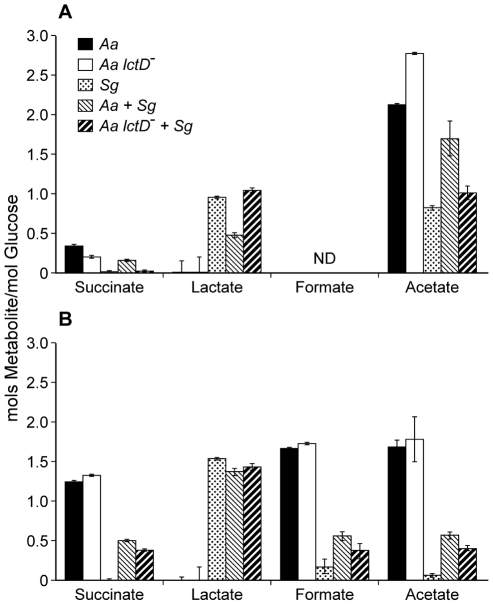

Examination of aerobic metabolic end products of the A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD-/S. gordonii co-culture revealed high levels of lactate, reminiscent of S. gordonii mono-cultures, indicating that as expected, the A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD mutant is unable to catabolize L-lactate in co-culture (Fig. 3A). Additionally, metabolite concentrations in anaerobic co-cultures were similar to S. gordonii mono-culture (Fig. 3B). It should be noted that these metabolites were measured from growing cells, not cell suspensions as in Fig. 1. These data provide strong evidence that the inability to use L-lactate, even when glucose is present, significantly inhibits A. actinomycetemcomitans growth and survival in co-culture.

Figure 3. Metabolite production by A. actinomycetemcomitans, A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD -, and S. gordonii in aerobic or anaerobic co-cultures.

Supernatants of the cultures used for CFU measurements in Fig. 2 were analyzed by HPLC for metabolite production from (A), aerobic or (B), anaerobic cultures. Data is presented as moles of metabolite produced/mole of glucose consumed. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 3. ND = No Data.

Interestingly, an approximate 7-fold increase in S. gordonii cell numbers were observed in the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans aerobically, indicating that A. actinomycetemcomitans enhances S. gordonii proliferation under these co-culture conditions even when A. actinomycetemcomitans is unable to utilize L-lactate (Fig. S1 in Text S1). Importantly, the pH of the medium used in these experiments remained at neutrality; thus changes in cell numbers were not due to alterations in pH.

L-lactate consumption is required for co-culture growth of A. actinomycetemcomitans in vivo

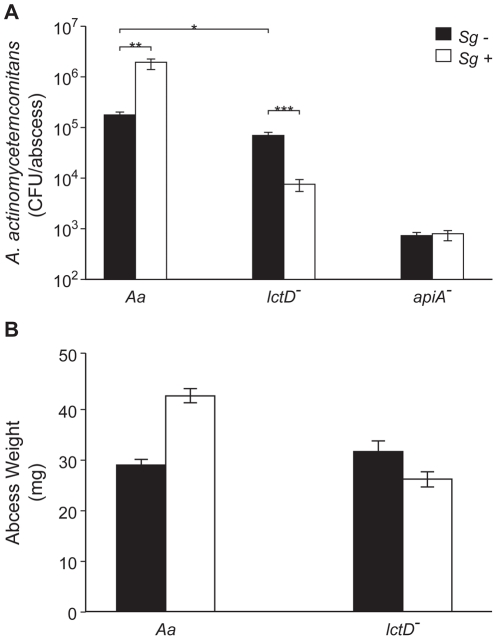

The observation that L-lactate catabolism is critical for A. actinomycetemcomitans to establish co-culture with S. gordonii in vitro provides new insight into this model polymicrobial community; however, whether the requirement for this catabolic pathway extended to in vivo co-culture was not known. To examine the role of A. actinomycetemcomitans L-lactate catabolism for in vivo growth in mono- and co-culture, we used a mouse thigh abscess model. This model has relevance as A. actinomycetemcomitans causes abscess infections outside of the oral cavity in close association with other bacteria [34] and has been used as a model system to examine pathogenesis of several oral bacteria [35], [36]. Using this model, bacterial survival and abscess formation was assessed for wt A. actinomycetemcomitans and A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - during mono- and co-culture with S. gordonii (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Persistence of A. actinomycetemcomitans, A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD -, and A. actinomycetemcomitans apiA - in mono- or co-culture in a murine abscess model.

A. Bacterial colony forming units per abscess. Wilcoxon signed-rank test values are: * p<0.02, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.008. B. Abscess weights 6 days post-inoculation. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 9. p<0.05 for wt A. actinomycetemcomitans in mono- and co-culture via Student's t-test.

Unexpectedly, wt A. actinomycetemcomitans and the lctD mutant established similar infections in terms of cell number (Fig. 4A) and in abscess weight (Fig. 4B) indicating that host-derived L-lactate is not an important in vivo nutrient source during mono-culture infection. Interestingly, wt A. actinomycetemcomitans displayed a 10-fold increase in cell number when co-cultured with S. gordonii, while cell number of the lctD mutant declined >100-fold compared to the wild-type providing evidence that the ability to catabolize L-lactate is crucial for A. actinomycetemcomitans co-culture survival in vivo. These data also indicate that while not critical for mono-culture growth, L-lactate is an important energy source during co-culture infection. Unlike the in vitro experiments (Fig. S1 in Text S1), S. gordonii numbers were not statistically different in monoculture or in co-culture abscesses (2.7×107 and 1.3×107 CFU/ml respectively; p = 0.15 via Mann-Whitney test) indicating that S. gordonii does not receive a benefit, at least in regard to cell number, from co-culture with A. actinomycetemcomitans. As a control, in vivo growth of the A. actinomycetemcomitans apiA mutant, which is hypersusceptible to killing by innate immunity, was examined. As expected, the apiA mutant exhibited a >250-fold decrease in mono-culture in vivo survival, which was unchanged in the presence of S. gordonii (Fig. 4A).

Discussion

Microbes within polymicrobial infections often display synergistic interactions that result in enhanced colonization and persistence in the infection site [5], [34], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. Such interactions have been particularly noted in oral polymicrobial infections, although the molecular processes controlling these synergistic interactions are not well defined. Detailed mechanistic studies of the interactions required for enhanced persistence in vivo is a critical step towards a more comprehensive understanding of natural polymicrobial infections. In this study, we used a model polymicrobial infection [6], [7] to determine the importance of metabolic cross-feeding for establishing co-culture infections. Cross-feeding in polymicrobial populations has been reported in numerous studies [24], [41], [42], but its importance for establishing co-culture infections has not been investigated in depth. The methodology used in this study began with detailed studies of the metabolic pathways required for growth with the in vivo carbon sources glucose and L-lactate, followed by examination of the importance of specific catabolic pathways for establishing co-culture infections.

It is relevant to discuss the rationale for two in vivo experimental parameters: using a ‘smooth’ strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans in lieu of a ‘rough’ strain; and using a murine abscess model in lieu of a rat periodontal infection model [43], [44]. A “smooth” strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans, which displays impaired surface attachment, was used in this study [45], [46]. As we were not investigating attachment or biofilm development, we opted to utilize a smooth strain that had undergone robust metabolic characterization, and feel this decision is justified as this bacterium clearly causes abscess infections in this model (Fig. 4). The murine abscess model was used for several reasons. First, in addition to periodontal infections, A. actinomycetemcomitans causes abscess infections outside of the oral cavity that resemble, from a gross morphological standpoint, the abscess model infection [34]; thus the abscess model has clinical relevance. Second, the abscess model avoids complications arising from the normal flora, which are not completely eradicated in the periodontal rat infection models, and whose presence would make interpretation of metabolic interactions extraordinarily complex. Third, the abscess model allows direct, controlled inoculation with a finite number of cells that can be quantified throughout the infection by assessing colony forming units after removal of the entire abscess [37], [47], [48]. Finally, although the abscess model has primarily been used to study anaerobic pathogens [35], [36], it is also relevant for studying aerobic pathogens, demonstrated by the large abscesses [48] formed by the strict aerobe Acinetobacter baumanii [17], [49]. The presence of aerobic microenvironments in the abscess is also supported by our observations that the S. gordonii spxB mutant is significantly impaired for abscess formation (Fig. S2 in Text S1). The spxB gene encodes pyruvate oxidase which utilizes O2 for biosynthesis of the virulence factor H2O2 [50]; thus its importance is limited to aerobic infections.

The observation that A. actinomycetemcomitans requires O2 to catabolize L-lactate was surprising, as many oral bacteria grow on L-lactate anaerobically [24], [31]. These results also solve an apparent contradiction in the literature. It was reported by multiple sources [17], [51] that A. actinomycetemcomitans does not catabolize L-lactate, yet we recently provided evidence that several strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans grow aerobically with L-lactate as the sole energy source [6], [29]. Interrogation of the previous growth environments revealed that A. actinomycetemcomitans was grown under very low or O2 free conditions; thus it is not surprising that significant growth was not observed in these studies. The O2 dependency of L-lactate oxidation also highlights another facet of our in vivo data. In the murine abscess model, the A. actinomycetemcomitans wt and lctD mutant grew equally well in mono-culture (Fig 4). However, in co-culture only the survival of the lctD mutant was impaired. This result is reminiscent of our in vitro data (Fig. 2) suggesting that O2 dependent metabolism occurs in our model polymicrobial infection.

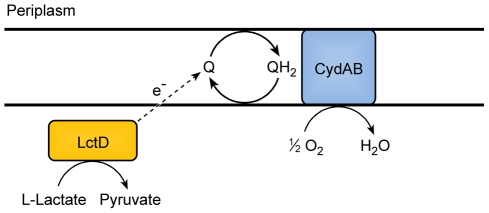

The observation that the terminal oxidase CydB is required for aerobic growth with L-lactate allows development of a new model for L-lactate consumption in A. actinomycetemcomitans (Fig. 5). Since L-lactate dehydrogenase (LctD) is necessary for lactate oxidation and does not use NAD+ as an electron acceptor [29], anaerobic fermentation pathways that regenerate NAD+ cannot act as electron acceptors for L-lactate oxidation. The model predicts that A. actinomycetemcomitans instead donates electrons directly to the quinone pool which in turn is re-oxidized by CydAB [52]. It should be noted that this does not rule out an unknown electron carrier between LctD and the membrane associated quinone.

Figure 5. Model for electron transport during L-lactate oxidation in A. actinomycetemcomitans.

A. actinomycetemcomitans requires O2 for oxidation of L-lactate. LctD may donate electrons from L-lactate directly to the quinone pool or utilize an unknown intermediate electron carrier represented by the dotted arrow. The cytochrome oxidase CydAD ultimately donates the electrons to O2.

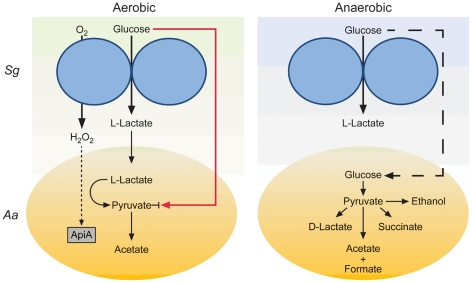

The most exciting observation from these studies is that L-lactate catabolism is likely an important factor for A. actinomycetemcomitans to establish a polymicrobial, but not mono-culture, infection in a murine abscess model (Fig. 4). These data indicate that host-produced L-lactate is not a vital energy source for A. actinomycetemcomitans in mono-culture abscesses, but when S. gordonii is present, L-lactate catabolism becomes critical. We speculate that in the absence of S. gordonii, carbohydrates such as glucose are present in the infection site for A. actinomycetemcomitans growth. When S. gordonii is introduced, competition for these carbohydrates increases, and A. actinomycetemcomitans is likely at a disadvantage due to its relatively slow growth and catabolic rates compared to S. gordonii [6]. Thus, the ability to preferentially utilize L-lactate, the primary metabolite produced by S. gordonii, allows A. actinomycetemcomitans to avoid competition with S. gordonii for carbohydrates and consequently enhance its survival in the abscess. This model (Fig. 6) suggests that the importance of individual carbon catabolic pathways is dependent on the context of the infection, specifically if oral streptococci are present.

Figure 6. Model for enhanced persistence of A. actinomycetemcomitans during aerobic co-culture with S. gordonii.

During co-culture aerobic growth with glucose, S. gordonii produces L-lactate and H2O2 which inhibit A. actinomycetemcomitans glucose uptake (red line) and induce apiA expression (dotted line) respectively. The production of L-lactate provides A. actinomycetemcomitans with a preferred carbon source for growth and reduces the need to compete with S. gordonii for glucose during aerobic co-culture. During anaerobic co-culture, S. gordonii also produces L-lactate but A. actinomycetemcomitans is unable to catabolize this carbon source due to the absence of O2; thus requiring A. actinomycetemcomitans to compete directly with S. gordonii for glucose (dashed line).

Our work demonstrates that metabolic pathways required for A. actinomycetemcomitans proliferation during mono-culture infection are distinct from those required for co-culture infection with a common commensal. This study provides strong evidence that simply because elimination of a catabolic pathway does not elicit a virulence defect in mono-species infection does not preclude it from being important in polymicrobial infections. Since metabolic interactions can potentially occur in virtually any polymicrobial infection, our results suggest that in some cases, the ability to cause infection will be as dependent on metabolic interactions as it is on known immune defense mechanisms and classical virulence factors. Our observations also have therapeutic implications, as development of small molecule inhibitors of metabolic pathways, particularly pathways restricted to prokaryotic pathogens, have promise as new therapeutic targets. Based on this study, efforts to develop such therapeutics will require a detailed understanding of how polymicrobial cross-feeding affects colonization and persistence in an infection site.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (Protocol Number: 09039).

Strains and media

A. actinomycetemcomitans strains VT1169 [53], Streptococcus gordonii strain Challis DL1.1 (ATCC 49818), S. gordonii spxB - [50], Escherichia coli DH5α-λpir, and E. coli SM10-λpir were used in this study. A. actinomycetemcomitans and S. gordonii were routinely cultured using Tryptic Soy Broth + 0.5% Yeast Extract (TSBYE). For resting cell suspension A. actinomycetemcomitans metabolite analysis, a Chemically Defined Medium (CDM) [6] lacking nucleotides, amino acids, pimelate and thioctic acid (to eliminate further cell growth) containing either 20 mM glucose or 40 mM L-lactate was used. For co-culture experiments, complete CDM with 3 mM glucose was used. Aerobic culture conditions were 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere shaking at 165 RPM, and anaerobic culture conditions were static growth at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (Coy, USA) with a 5% H2, 10% CO2 and 85% N2 atmosphere. E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. Where applicable, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol, 2 µg/ml for A. actinomycetemcomitans and 20 µg/ml for E. coli; spectinomycin, 50 µg/ml for selection and 10 µg/ml for maintenance for A. actinomycetemcomitans and E. coli and 100 µg/ml for selection and maintenance for S. gordonii spxB -; kanamycin, 40 µg/ml for selection and 10 µg/ml for maintenance; naladixic acid, 25 µg/ml; streptomycin, 50 µg/ml for selection and 20 µg/ml for maintenance. For quantifying CFU/ml in co-culture assays, vancomycin (5 µg/ml) was added to agar plates to enumerate A. actinomycetemcomitans and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) was added to agar plates to enumerate S. gordonii.

DNA and plasmid manipulations

DNA and plasmid isolations were performed using standard methods [54]. Restriction endonucleases and DNA modification enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Chromosomal DNA from A. actinomycetemcomitans was isolated using DNeasy tissue kits (Qiagen), and plasmid isolations were performed using QIAprep spin miniprep kits (Qiagen). DNA fragments were purified using QIAquick mini-elute PCR purification kits (Qiagen), and PCR was performed using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche). DNA sequencing was performed by automated sequencing technology using the University of Texas Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology sequencing core facility.

A. actinomycetemcomitans apiA mutant construction

Allelic replacement of apiA (AA2485) was carried out by double homologous recombination. For construction of the knockout construct, 856 bp and 842 bp DNA fragments flanking apiA were amplified and combined with the aphA gene (encoding kanamycin resistance) from pBBR1-MCS2 [55] by overlap extension PCR [56]. The construct was prepared so that aphA was positioned between the upstream and downstream regions. Primers used were: Kan-5′ (ATGTCAGCTACTGGGCTATCTG) and Kan-3′ (ATTTCGAACCCCAGAGTCCCGC) for the 1074 bp aphA-containing fragment; ApiA-UF (CCGATAACAGTAAGATCTTCTAC) and ApiA-UR (CAGATAGCCCAGTAGCTGACAT CCTTTTCGGCTTGAATTTATACC) for the upstream apiA fragment; and ApiA-DF (GCGGGACTCTGGGGTTCGAAAT GCGGTCAGAATTTTAGGTGTTTT) and ApiA-DR (CGAAACCAACGAACTCTTTATTC) for the downstream apiA fragment. Underlined sequences indicate overlapping DNA sequences between the apiA fragments and aphA. The overlap extension product was TA-cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA) and excised by EcoRI digest. The EcoRI fragment containing the overlap extension product was ligated into the unique EcoRI site within the λpir-dependent suicide vector pVT1461 [57]. The cloned construct, pVT1461-apiA-KO, was first transformed into E. coli DH5α-λpir then into E. coli SM10-λpir for conjugation into A. actinomycetemcomitans. Conjugation was performed as described [53] and potential mutants were plated onto TSBYE agar plates containing kanamycin to select for recombinant A. actinomycetemcomitans and nalidixic acid to kill the E. coli donors. Kanamycin resistant, spectinomycin sensitive double recombinants were selected and verified by PCR. Enhanced susceptibility of the apiA mutant to serum was verified as described previously [7].

A. actinomycetemcomitans cydB mutant construction

Insertional mutagenesis of the cydB gene was performed by single homologous recombination using a 543 bp internal piece of the cydB (AA2840) gene amplified using the primers cydB-KO5′ (GAAGATCTTTATGATTAATACTATCGCGCCG) and cydB-KO3′ (GAAGATCTCAAAACCATCTTTGAAAGATAACCA). Underlined sequences represent BglII restriction sites. The internal cydB fragment was digested with BglII and ligated into the A. actinomycetemcomitans suicide vector pMRKO-1 (see below) to generate pMRKO-cydB. pMRKO-cydB was transformed into E. coli SM10-λpir and conjugated into A. actinomycetemcomitans. A. actinomycetemcomitans recombinants were grown anaerobically on TSBYE agar containing spectinomycin and naladixic acid. Colonies were subcultured anaerobically on liquid medium at the same antibiotic concentrations and insertion into cydB was verified by PCR.

pMRKO-1 suicide vector construction

The spectinomycin resistance gene from pDMG4 [58] was amplified by PCR using the primers: 5′Spec-cass-NotI (ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCCGATTTTCGTTCGTGAATACATG) and 3′ Spec-cass-EcoRI (CGGAATTCCATATGCAAGGGTTTATTGTTT), digested with NotI-EcoRI and ligated into NotI-EcoRI digested pmCherry (Clontech) underlined sequences indicate NotI and EcoRI restriction sites. The 3105 bp region containing the pUC origin of replication, plac:mCherry and the spectinomycin resistance gene were PCR amplified using the primers: 5′pMcher-trunc (GAAGATCTGACCAAGTTTACTCATATATACT) and 3′ Spec-cass-EcoRI (CGGAATTCCATATGCAAGGGTTTATTGTTT). Underlined sequences indicate BglII and EcoRI restriction sites. This fragment was digested with BglII and EcoRI and ligated into the 2780 bp fragment from BglII-EcoRI digested pVT1461. The resulting plasmid (pMRKO-1, submitted to Genbank) is a suicide vector for A. actinomycetemcomitans and contains oriT, mob, and tra genes from pVT1461 along with the pUC origin of replication, mCherry expressed from plac, and a spectinomycin resistance cassette.

Resting cell suspensions

A. actinomycetemcomitans was grown in CDM overnight either aerobically or anaerobically in the presence of 20 mM glucose or 40 mM L-lactate. Bacteria were then subcultured in 30 ml of medium and exponential phase cells (OD600 = 0.4) were collected by centrifugation (5,000 x g for 15 min) at 25°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in an equal volume of CDM lacking nucleotides, amino acids and any carbon source. Cells were incubated at 37°C aerobically or anaerobically depending on the test conditions for 1 hr. Cells were collected again by centrifugation as described above and resuspended to an OD600 of 2 in 3 ml of CDM without nucleotides, amino acids, pimelate and thioctic acid containing either 20 mM glucose or 40 mM lactate. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C either aerobically or anaerobically. After incubation samples were stored at −20°C for HPLC analysis.

D-Lactate assay

D-lactate assays were performed as described [30] with modifications. Glycylglycine buffer was replaced with an equal concentration of Bicine (Fisher, USA) buffer and enzymatic assays were monitored by spectrophotometry at 340 nm for 4 hours.

Co-culture experiments

A. actinomycetemcomitans and S. gordonii were grown overnight in CDM containing 3 mM glucose. 3 mM glucose was used to ensure that the medium was limited for catabolizable carbon. Cells were diluted 1∶50 in the same medium and allowed to grow to exponential phase (OD600 of 0.2). Cells were then diluted 1∶100 (2×106 S. gordonii/ml and 1×107 A. actinomycetemcomitans/ml) as mono-cultures or co-cultures in 3 ml CDM containing 3 mM glucose. Cultures were allowed to grow for 10 h aerobically or 12 h anaerobically, after which cells were serially diluted, plated on either TSBYE agar + vancomycin for A. actinomycetemcomitans enumeration or TSBYE agar + streptomycin for S. gordonii enumeration. Colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C for 48 h. An aliquot of the culture was also stored at −20°C for HPLC metabolite analysis.

HPLC analysis

Metabolite levels were quantified using a Varian HPLC with a Varian Metacarb 87H 300×6.5 mm column at 35°C. Samples were eluted using isocratic conditions with 0.025 N H2SO4 elution buffer and a flow rate of 0.5 ml/minute. A Varian refractive index (RI) detector at 35°C was used for metabolite enumeration by comparison with acetate, ethanol, formate, glucose, L-lactate, D-lactate, pyruvate and succinate standards.

In vivo murine abscess growth

Murine abscesses were generated essentially as described previously [37]. Briefly, 6–8 week-old, female, Swiss Webster mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Nembutal (50 mg/kg). The hair on the left inner thigh of each mouse was shaved, and the skin was disinfected with 70% alcohol. Mice were injected subcutaneously in the inner thigh with 107 CFU A. actinomycetemcomitans, S. gordonii or both. At 6 days post- infection, mice were euthanized and intact abscesses were harvested, weighed and placed into 2 ml of sterile PBS (or water for pH measurements). Tissues were homogenized, serially diluted and plated on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar + 20 µg/ml Na2CO3 + vancomycin for A. actinomycetemcomitans enumeration or BHI agar + 20 µg/ml Na2CO3 + streptomycin for S. gordonii enumeration, to determine bacterial CFU/abscess. Experimental protocols involving mice were examined and approved by the Texas Tech University HSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Supporting Information

Figure S1: Growth of S. gordonii in mono- or co-culture with A. actinomycetemcomitans or A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - in aerobic and anaerobic co-cultures. Strains were grown as mono- or co-cultures in 3 mM glucose aerobically or anaerobically for 10 or 12 h respectively, serially diluted, and plated on selective media to determine colony forming units per ml (CFU/ml). S. gordonii mono-cultures numbers are represented by black bars, co-culture numbers with A. actinomycetemcomitans are represented by white bars, and co-culture numbers with A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - are represented by grey bars. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 3. Figure S2: Survival of S. gordonii and S. gordonii spxB - in a murine abscess model. A. Number of bacteria recovered from each abscess expressed as colony forming units per abscess (CFU/abscess). Wilcoxon signed-rank test value, p<0.03. B. Abscess weights 6 days post-inoculation. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 4.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Whiteley lab and our reviewers for critical discussion of this manuscript and Dr. Jens Kreth for the generous gift of the S. gordonii spxB - mutant. MW is a Burroughs Wellcome Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was funded by grants from the NIH (5R01AI075068 to MW and 5F31DE019995 to MW and MMR). MW is a Burroughs Wellcome Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Brown SA, Palmer KL, Whiteley M. Revisiting the host as a growth medium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:657–666. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouqui P, Raoult D. Endocarditis due to rare and fastidious bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:177–207. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.177-207.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkinson HF, Lamont RJ. Oral microbial communities in sickness and in health. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuramitsu HK, He X, Lux R, Anderson MH, Shi W. Interspecies interactions within oral microbial communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:653–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakaletz LO. Developing animal models for polymicrobial diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:552–568. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown SA, Whiteley M. A novel exclusion mechanism for carbon resource partitioning in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6407–6414. doi: 10.1128/JB.00554-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey MM, Whiteley M. Polymicrobial interactions stimulate resistance to host innate immunity through metabolite perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1578–1583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809533106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich LE, Price-Whelan A, Petersen A, Whiteley M, Newman DK. The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebersole JL, Cappelli D, Sandoval MN. Subgingival distribution of A. actinomycetemcomitans in periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer DH, Fives-Taylor PM. Oral pathogens: from dental plaque to cardiac disease. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:88–95. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loesche WJ, Gusberti F, Mettraux G, Higgins T, Syed S. Relationship between oxygen tension and subgingival bacterial flora in untreated human periodontal pockets. Infect Immun. 1983;42:659–667. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.2.659-667.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courts FJ, Boackle RJ, Fudenberg HH, Silverman MS. Detection of functional complement components in gingival crevicular fluid from humans with periodontal diseases. J Dent Res. 1977;56:327–331. doi: 10.1177/00220345770560032001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamaguchi M, Kawabata Y, Kambe S, Wardell K, Nystrom FH, et al. Non-invasive monitoring of gingival crevicular fluid for estimation of blood glucose level. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2004;42:322–327. doi: 10.1007/BF02344706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciantar M, Spratt DA, Newman HN, Wilson M. Development of an in vitro microassay for glucose quantification in submicrolitre volumes of biological fluid. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:79–85. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serra E, Perinetti G, D'Attilio M, Cordella C, Paolantonio M, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase activity in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:206–211. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamster IB, Hartley LJ, Oshrain RL, Gordon JM. Evaluation and modification of spectrophotometric procedures for analysis of lactate dehydrogenase, beta-glucuronidase and arylsulphatase in human gingival crevicular fluid collected with filter-paper strips. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergey DH. Bergey's Manual of Determinitive Bacteriology. In: Holt JG, editor. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dzink JL, Tanner AC, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Gram negative species associated with active destructive periodontal lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:648–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreth J, Merritt J, Qi F. Bacterial and host interactions of oral streptococci. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:397–403. doi: 10.1089/dna.2009.0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Blehert DS, Egland PG, Foster JS, et al. Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:486–505. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.486-505.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore WE, Holdeman LV, Smibert RM, Hash DE, Burmeister JA, et al. Bacteriology of severe periodontitis in young adult humans. Infect Immun. 1982;38:1137–1148. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.3.1137-1148.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syed SA, Loesche WJ. Bacteriology of human experimental gingivitis: effect of plaque age. Infect Immun. 1978;21:821–829. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.3.821-829.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook GS, Costerton JW, Lamont RJ. Biofilm formation by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus gordonii. J Periodontal Res. 1998;33:323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egland PG, Palmer RJ, Jr, Kolenbrander PE. Interspecies communication in Streptococcus gordonii-Veillonella atypica biofilms: signaling in flow conditions requires juxtaposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16917–16922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407457101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asakawa R, Komatsuzawa H, Kawai T, Yamada S, Goncalves RB, et al. Outer membrane protein 100, a versatile virulence factor of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1125–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kononen E, Paju S, Pussinen PJ, Hyvonen M, Di Tella P, et al. Population-based study of salivary carriage of periodontal pathogens in adults. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2446–2451. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02560-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sirinian G, Shimizu T, Sugar C, Slots J, Chen C. Periodontopathic bacteria in young healthy subjects of different ethnic backgrounds in Los Angeles. J Periodontol. 2002;73:283–288. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nuttall FQ, Khan MA, Gannon MC. Peripheral glucose appearance rate following fructose ingestion in normal subjects. Metabolism. 2000;49:1565–1571. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.18553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown SA, Whiteley M. Characterization of the L-lactate dehydrogenase from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talasniemi JP, Pennanen S, Savolainen H, Niskanen L, Liesivuori J. Analytical investigation: assay of D-lactate in diabetic plasma and urine. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolenbrander P. The genus Veillonella. In: Dworkin M, editor. The Prokaryotes.Third ed. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 1022–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, Kittichotirat W, Si Y, Bumgarner R. Genome sequence of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans serotype c strain D11S-1. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7378–7379. doi: 10.1128/JB.01203-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Kittichotirat W, Chen W, Downey JS, Si Y, et al. Genome sequence of naturally competent Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans serotype a strain D7S-1. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2643–2644. doi: 10.1128/JB.00157-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan AH, Weber DJ, Oddone EZ, Perfect JR. Infection due to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: 15 cases and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:46–63. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ebersole JL, Kesavalu L, Schneider SL, Machen RL, Holt SC. Comparative virulence of periodontopathogens in a mouse abscess model. Oral Dis. 1995;1:115–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1995.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kesavalu L, Holt SC, Ebersole JL. Virulence of a polymicrobic complex, Treponema denticola and Porphyromonas gingivalis, in a murine model. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:373–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mastropaolo MD, Evans NP, Byrnes MK, Stevens AM, Robertson JL, et al. Synergy in polymicrobial infections in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6055–6063. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6055-6063.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozarov EV, Dorn BR, Shelburne CE, Dunn WA, Jr, Progulske-Fox A. Human atherosclerotic plaque contains viable invasive Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:e17–18. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000155018.67835.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagashima H, Takao A, Maeda N. Abscess forming ability of streptococcus milleri group: synergistic effect with Fusobacterium nucleatum. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen PB, Davern LB, Katz J, Eldridge JH, Michalek SM. Host responses induced by co-infection with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in a murine model. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:274–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Periasamy S, Kolenbrander PE. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans builds mutualistic biofilm communities with Fusobacterium nucleatum and Veillonella species in saliva. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3542–3551. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00345-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz JE, Breznak JA. Cross-Feeding of Lactate Between Streptococcus lactis and Bacteroides sp. Isolated from Termite Hindguts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:1206–1210. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.6.1206-1210.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kesavalu L, Sathishkumar S, Bakthavatchalu V, Matthews C, Dawson D, et al. Rat model of polymicrobial infection, immunity, and alveolar bone resorption in periodontal disease. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1704–1712. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00733-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fine DH, Goncharoff P, Schreiner H, Chang KM, Furgang D, et al. Colonization and persistence of rough and smooth colony variants of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the mouths of rats. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(01)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fine DH, Furgang D, Kaplan J, Charlesworth J, Figurski DH. Tenacious adhesion of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strain CU1000 to salivary-coated hydroxyapatite. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fine DH, Furgang D, Schreiner HC, Goncharoff P, Charlesworth J, et al. Phenotypic variation in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans during laboratory growth: implications for virulence. Microbiology. 1999;145(Pt 6):1335–1347. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han G, Martinez LR, Mihu MR, Friedman AJ, Friedman JM, et al. Nitric oxide releasing nanoparticles are therapeutic for Staphylococcus aureus abscesses in a murine model of infection. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fetiye K, Karadenizli A, Okay E, Oz S, Budak F, et al. Comparison in a rat thigh abscess model of imipenem, meropenem and cefoperazone-sulbactam against Acinetobacter baumannii strains in terms of bactericidal efficacy and resistance selection. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2004;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dworkin M, Falkow S. New York ;[London]: Springer; 2006. The prokaryotes : a handbook on the biology of bacteria. pp. v.1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kreth J, Zhang Y, Herzberg MC. Streptococcal Antagonism In Oral Biofilms: Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii interference with Streptococcus mutans. . J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4632–4640. doi: 10.1128/JB.00276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slots J, Reynolds HS, Genco RJ. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease: a cross-sectional microbiological investigation. Infect Immun. 1980;29:1013–1020. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.3.1013-1020.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamada H, Takashima E, Konishi K. Molecular characterization of the membrane-bound quinol peroxidase functionally connected to the respiratory chain. FEBS J. 2007;274:853–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mintz KP, Fives-Taylor PM. impA, a gene coding for an inner membrane protein, influences colonial morphology of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6580–6586. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6580-6586.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ausubel FM. 2 v. New York: Wiley; 2002. Short protocols in molecular biology : a compendium of methods from Current protocols in molecular biology. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, et al. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mintz KP, Brissette C, Fives-Taylor PM. A recombinase A-deficient strain of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans constructed by insertional mutagenesis using a mobilizable plasmid. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;206:87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb10991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galli DM, Polan-Curtain JL, LeBlanc DJ. Structural and segregational stability of various replicons in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Plasmid. 1996;36:42–48. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Growth of S. gordonii in mono- or co-culture with A. actinomycetemcomitans or A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - in aerobic and anaerobic co-cultures. Strains were grown as mono- or co-cultures in 3 mM glucose aerobically or anaerobically for 10 or 12 h respectively, serially diluted, and plated on selective media to determine colony forming units per ml (CFU/ml). S. gordonii mono-cultures numbers are represented by black bars, co-culture numbers with A. actinomycetemcomitans are represented by white bars, and co-culture numbers with A. actinomycetemcomitans lctD - are represented by grey bars. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 3. Figure S2: Survival of S. gordonii and S. gordonii spxB - in a murine abscess model. A. Number of bacteria recovered from each abscess expressed as colony forming units per abscess (CFU/abscess). Wilcoxon signed-rank test value, p<0.03. B. Abscess weights 6 days post-inoculation. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean, n = 4.

(DOC)