Abstract

Dorsal root (DR) axons regenerate in the PNS but turn around or stop at the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ), the entrance into the CNS. Earlier studies that relied on conventional tracing techniques or postmortem analyses attributed the regeneration failure to growth inhibitors and lack of intrinsic growth potential. Here, we report the first in vivo imaging study of DR regeneration. Fluorescently labeled, large-diameter DR axons in thy1-YFPH mice elongated through a DR crush site, but not a transection site, and grew along the root at >1.5 mm/d with little variability. Surprisingly, they rarely turned around at the DREZ upon encountering astrocytes, but penetrated deeper into the CNS territory, where they rapidly stalled and then remained completely immobile or stable, even after conditioning lesions that enhanced growth along the root. Stalled axon tips and adjacent shafts were intensely immunolabeled with synapse markers. Ultrastructural analysis targeted to the DREZ enriched with recently arrived axons additionally revealed abundant axonal profiles exhibiting presynaptic features such as synaptic vesicles aggregated at active zones, but not postsynaptic features. These data suggest that axons are neither repelled nor continuously inhibited at the DREZ by growth-inhibitory molecules but are rapidly stabilized as they invade the CNS territory of the DREZ, forming presynaptic terminal endings on non-neuronal cells. Our work introduces a new experimental paradigm to the investigation of DR regeneration and may help to induce significant regeneration after spinal root injuries.

Introduction

Almost a century ago, Ramón y Cajal labeled a subset of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) axons with Golgi staining and showed that regenerating dorsal root (DR) axons were redirected peripherally or terminated at the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ), the transitional zone between the CNS and PNS (Ramón y Cajal, 1928). This regeneration failure remains an important practical issue because common spinal root injuries, such as brachial plexus or cauda equina injuries, lack effective therapy (Hannila and Filbin, 2008; Havton and Carlstedt, 2009). The molecular and cellular events that repel or arrest axons at the DREZ remain poorly understood, but this regeneration failure is generally attributed to glia-associated growth-inhibitory molecules and lack of intrinsic growth potential of DRG neurons (Ramer et al., 2001a).

Although spinal root injury evokes changes similar to those induced by direct CNS injury, it does not cause an impassable glial scar. Nevertheless, the axotomized DREZ prevents regeneration efficiently: Whereas peripheral conditioning lesions, which enhance the growth potential of DRG neurons, promote intraspinal regeneration of their central axons in the dorsal columns (Neumann and Woolf, 1999; Cao et al., 2006), the same axons fail to regenerate through the DREZ (Chong et al., 1999; Golding et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2007). Notably, repellent cues, including oligodendrocyte-associated inhibitors (Nogo, MAG, and OMgp) and astrocyte-associated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), cause only brief growth cone collapse or retraction (Snow et al., 1991; Li et al., 1996; Yiu and He, 2006). Moreover, DRG axons grow despite growth cone collapse (Marsh and Letourneau, 1984; Jones et al., 2006; Jin et al., 2009). These growth-inhibitory molecules therefore seem to account for the turning but not the arrest of DR axons at the DREZ. These considerations led us to suspect that a novel mechanism plays a more decisive role in preventing regeneration across the DREZ.

Previous studies relied heavily on conventional tracing techniques and postmortem analyses. The spatial and temporal resolutions of these studies were limited: one could only deduce dynamic events associated with DR regeneration by comparing static images. Fundamental questions therefore remained unanswered, including whether axons stop abruptly or attempt to turn around at the DREZ and whether they remain immobile or regain mobility over time. Axon turning would suggest that the DREZ functions as a passive barrier that axons avoid. Brief collapse without permanent immobilization would highlight the importance of repulsive growth inhibitors that continuously collapse axons at the DREZ. On the other hand, rapid, permanent immobilization would suggest a unique mechanism that arrests axons by paralyzing or stabilizing them, as was speculated many years ago but virtually forgotten (Carlstedt, 1985; Liuzzi and Lasek, 1987).

To address these questions, we applied in vivo imaging techniques using fluorescent transgenic mice with a vital Golgi-like stain, and monitored the regeneration of identified DR axons repeatedly over weeks to months directly in living animals with and without conditioning lesions. Combined with a targeted ultrastructural analysis, we found that most axons were not repelled, but were immobilized rapidly and chronically at the DREZ, forming presynaptic terminal endings in its CNS territory.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

We used adult mice (2–4 months of age) of either sex from transgenic strains thy1-YFPH and thy1-YFP16, which express yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) under the control of the neuron-specific Thy-1 promoter (Feng et al., 2000). The original breeding pairs were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory; subsequent stocks of mice used in these experiments were reared in the animal facilities at Drexel University College of Medicine (DUCOM). All experiments were performed in accordance with DUCOM's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Surgical and postoperative procedures.

Thy1-YFPH mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of xylazine (8 mg/kg) and ketamine (120 mg/kg). Supplements were given during the procedure as needed. A 2- to 3-cm-long incision was made in the skin of the back; the spinal musculature was reflected; and the L3–S1 spinal cord segments were exposed by hemilaminectomies. The cavity made by the laminectomies was perfused with warm sterile Ringer's solution or artificial CSF. A small incision was made in the dura overlying the L5 dorsal root near the L3 DRG; a fine forceps (Dumont #5) was introduced subdurally and the L5 dorsal root was crushed for 10 s. After images were collected (see below), we attempted to minimize scar formation by tightly applying a piece of thin synthetic matrix membrane (Biobrane, Bertek Pharmaceuticals) over the exposed cord and dura, so that scarring accumulated on the membrane rather than on the dura surface. The matrix membrane was removed and replaced at each imaging session. This membrane was stabilized with a layer of much thicker artificial dura (Gore Preclude MVP Dura Substitute, W.L. Gore and Associates) that covered the laminectomy site. The musculature was then closed with sterile 5-0 sutures, and the skin with wound clips. Animals were given subcutaneous injections of lactated Ringer's solution to prevent dehydration and kept on a heating pad until fully recovered from anesthesia. Buprenorphine was given as postoperative analgesia (0.05 mg/kg, s.c., every 12 h for 2 d). For each imaging session, we reanesthetized and surgically reexposed the area of interest and repeated the procedures. For conditioning lesions, the sciatic nerve was crushed in the lateral thigh of the ipsilateral hind leg 10 d before the root was crushed. Animals were anesthetized as described above; the skin and superficial muscle layer of the midthigh were opened; and the sciatic nerve was crushed for 10 s with fine forceps (Dumont #5). The muscle and skin were then closed in layers and the animals were allowed to recover on a heating pad until fully awake.

In vivo imaging and image acquisition.

We used a Leica MZ16 fluorescent stereomicroscope or an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a fast shutter and a highly sensitive cooled CCD camera (ORCA-Rx2, Hamamatsu) controlled by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Body temperature was maintained by placing the animal on a thermostatically controlled heating pad. Warmed lactated Ringer's solution was used to superfuse the exposed portion of spinal cord. Images were acquired either as single snapshots or as multiple streams of 10–20 frames acquired within 30–40 ms exposure time. In-focus images were then selected, and an overview montage was created using Photoshop (Adobe Systems). High-resolution confocal images were obtained with a Leica TCS 4D confocal microscope. Z stacks were obtained at 0.3 μm step size for 20–40 μm depths. Leica TCS-NT acquisition software and Imaris image software (Bitplane) were used to reconstruct z-series images into maximum-intensity projections.

Immunohistochemistry of DREZ in whole mounts.

Following in vivo imaging, we harvested tissues and processed them in whole mounts to immunolabel astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or Schwann cells to locate the CNS/PNS interface. The immunostaining procedure was standard (Wright et al., 2009), except for the permeabilization steps in which chilled MeOH and 1% sodium borohydride were also used. Mice were perfused transcardially with 0.9% heparinized saline solution followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After 3 h in situ postfixation at 4°C, the spinal cord segment (L3–L6) with attached dorsal roots was removed and rinsed in PBS. The tissue was then washed for 30 min in a blocking solution containing 0.1 m glycine and 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS and treated in cold MeOH for 10 min and then 1% sodium borohydride for 5–10 min. After thorough and extensive rinsing in PBS, the spinal cord was further permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 with 2% BSA in PBS (TBP) for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibody diluted in TBP overnight. The next day, the spinal cord was rinsed thoroughly in TBP and then incubated with appropriate fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies diluted in the TBP for 1 h at room temperature. The tissue was then rinsed in PBS, and a thin sheet of dorsal spinal cord was prepared from the DREZ and rootlet, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), and stored at 4°C.

Immunohistochemistry of DREZ on cryostat sections.

To immunolabel axons at the axotomized DREZ with synaptic vesicle markers, we used the transgenic strain, thy1-YFP16, in which the entire population of large-diameter axons expresses YFP (data not shown). To analyze more axons than superficially located ones, we prepared cryostat sections, rather than whole mounts, of the DREZ after crushing dorsal roots of cervical spinal cord. Using the surgical procedures described earlier, C3–C5 roots were crushed, and the animals were allowed to recover. At 20 d after injury, the C3–C5 spinal cord and roots were harvested, postfixed overnight at 4°C, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS, and rapidly frozen in Shandon M1 embedding matrix (Thermo Electron). Serial transverse sections were cut on a cryostat at 10 μm (CM3000, Leica) and collected on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). For immunostaining, sections were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, rinsed in PBS, and blocked for 1 h in TBP. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in a cocktail of primary antibodies diluted in TBP. Sections were then rinsed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies in TBP for 1 h at room temperature and processed as described above.

Analysis of thy1-YFPH DRGs.

L5 DRGs were dissected from unoperated thy1-YFPH mice and processed to obtain serial cryostat sections using the methods described above. Selected sections were stained with a fluorescent Nissl stain (Neurotrace 530/615 red fluorescent Nissl stain; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, washed extensively with PBS, and coverslipped using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Neuron counts were made on five L5 DRGs from three animals. For each DRG, at least three randomly selected sections were analyzed, taking care not to use sections that were poorly mounted or stained. Each section selected was at least 30 μm away (three sections) from either of the other selected sections. Using a Retiga EXi (Qimaging) digital camera, the entire section was photographed in segments using the 20× objective on a Leica DMRBE fluorescent microscope. The same section was photographed using both red (Nissl-stained cells) and green [YFP-positive (YFP+) cells] fluorescent filter cubes to identify neurons containing a nucleus with a visible nucleolus and to determine whether such neurons were YFP positive. Image segments were collected at 200× magnification and combined to form a montage. Using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), the cell area of all neurons containing a nucleus with a visible nucleolus from each chosen section was measured. We counted a minimum of 200 neurons per ganglion. If this number was not reached in the three sections chosen, a fourth section was counted, also in its entirety. However, because identification and counting continued even after the minimum of 200 neurons were obtained, we always counted >200 Nissl-stained neurons per DRG (mean 218 ± 6 Nissl cells measured/DRG, 4.3% of the measured were YFP+). Histograms representing the cross-sectional area of all Nissl- and YFP-labeled DRG neurons measured were compiled to compare the distribution of the YFP-labeled cells with the total cell populations.

Antibodies.

The primary, cell-type-specific antibodies included anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, mouse monoclonal, 1:1000, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents, Millipore) to label astrocytes, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG, goat polyclonal, 1:200, R&D Systems) for labeling oligodendrocytes and anti-SC/2E (mouse monoclonal, 1:1000, Cosmo Bio), or laminin-1 (rat monoclonal, 1:200, Abcam) to label Schwann cells. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to a synaptic vesicle protein, SV2 (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), or to synaptotagmin 2 (znp-1, 1:2000, Zebrafish International Resource Center) were used to label synaptic vesicles. To learn more about the phenotype of YFP+ DRG neurons, selected sections from L5 DRGs were labeled with one or more of the following methods: Neurons containing phosphorylated epitopes of high-molecular-weight neurofilament were identified using the SMI 312 antibody (mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:1000 dilution, Covance). The population of small primary afferent neurons that expresses the trkA neurotrophin receptor was labeled using an antibody to calcitonin gene-related polypeptide (CGRP, rabbit polyclonal antibody to rat CGRP, 1:2000, Bachem). The population of small DRG neurons that does not express the trkA neurotrophin receptor was labeled using Griffonia simplicifolia IB4 lectin (biotin conjugate, 5 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa 647-conjugated donkey anti-mouse 1:200, Invitrogen), Alexa-Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (1:200, Invitrogen), Alexa-Fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, Invitrogen), and rhodamine-red-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Electron microscopy of the DREZ.

The mice were perfused transcardially (with heparinized Tyrode's solution followed by 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m Na-cacodylate buffer. The spinal cord segments L3–L6 were then removed as one piece and rinsed in 0.1 m Na-cacodylate buffer, mounted on an agarose support, and placed in the vibratome well containing chilled buffer. The most superficial longitudinal slice containing the DREZ (<250 μm thickness) was cut and further processed for electron microscopy. To target our electron microscopic analysis to the area where axons had stalled, we applied fiducial markers to the surface of the spinal cord slice. The spinal cord sections were flattened with insect pins in Sylgard silicone elastomer-lined 35 mm Petri dishes. A 1.0% solution of 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine-5,5′-disulfonic acid (DiI, Invitrogen) was dissolved in dichloromethylene and loaded into a micropipette (resistance of 5–10 MΩ). Crystals of DiI were iontophoretically applied to the surface of the spinal cord slice in an area of the DREZ with bulb-tipped axons (e.g., see Fig. 11A). To render the DiI crystal electron dense, we excited the DiI crystals near their excitation wavelength in the presence of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, 5.0 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) until the DiI crystal was replaced with a dark red/brown DAB precipitate (∼20 min). After photoconversion, spinal cord slices were trimmed to contain the area of interest using the electron-dense fiducial markers as reference points. Tissue blocks were stained with 1.0% osmium tetroxide reduced in 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide for 45 min, then dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series, infiltrated with Araldite 502 Embed 812 resin, and polymerized at 60°C for 48 h. Polymerized tissue blocks were sectioned (0.5 μm) with a glass knife on a Leica Ultracut R microtome (Leica) until the fiducial markers were located. Serial ultrathin sections (60–70 nm) were cut and mounted on pioloform-coated slot grids. Sections were counterstained with 2.0% aqueous uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate. Sections were viewed at 75 kV on a Hitachi H-600 transmission electron microscope. Serial electron micrographs were captured at 6000× and scanned at a resolution of 1000 dpi.

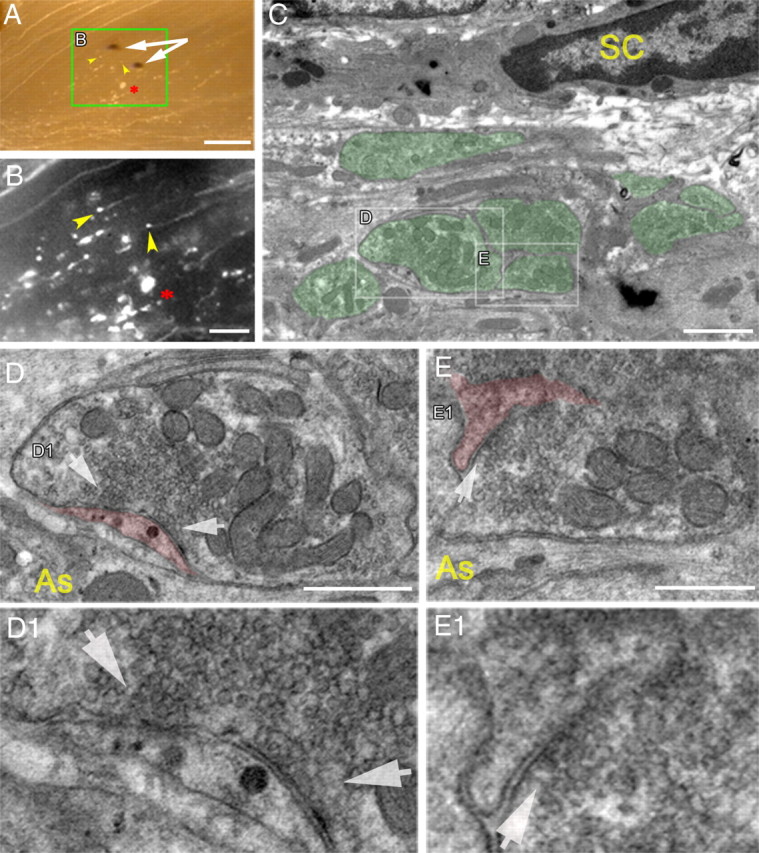

Figure 11.

Ultrastructural analysis of DR axons stopped at the DREZ, revealing presynaptic differentiation. The L5 root of a Thy1-YFPH mouse was crushed 13 d previously. A, Low-magnification, transmitted-light view, superimposed on fluorescence image, of the DREZ in a vibratome slice. Photoconverted DiI crystals (white arrows) were placed in an area where axons were stopped, and the area between the two crystals was examined in the transmission electron microscope. Yellow arrowheads point to two axon tips. The asterisk indicates axon debris and marks the same spot in B. B, Magnified fluorescent view of the boxed area in A. Axons stopped at the usual location in the DREZ, showing axonal debris (asterisk) and stalled axon tips (yellow arrowheads). C, An electron micrograph of the targeted area of the DREZ showing axonal profiles (pseudocolored green) embedded within non-neuronal cellular processes. D, Magnified view of a boxed area in C, revealing a nerve-terminal-like profile in contact with a non-neuronal cellular process (pseudocolored red). Note that the presynaptic profile is filled with differentially distributed mitochondria and abundant ∼40 nm vesicles but lacks vacuoles and disorganized microtubules. D1, An enlarged area of synaptic contact in D. Vesicles are highly clustered and docked at an electron-dense membrane that resembles an active zone (white arrows). No postsynaptic densities are present on the non-neuronal cell process. E, Magnified view of another area in C, revealing a nerve-terminal-like profile of an adjacent axon. E1, An enlarged area of synaptic contact in E. Note that this axon also shows presynaptic differentiation in contact with a fine non-neuronal cellular process (pseudocolored red) that does not exhibit postsynaptic densities. SC, Schwann cell; As, astrocyte. Scale bars: A, 250 μm; B, 100 μm; C, 1 μm; D, 250 nm; E, 200 nm.

Results

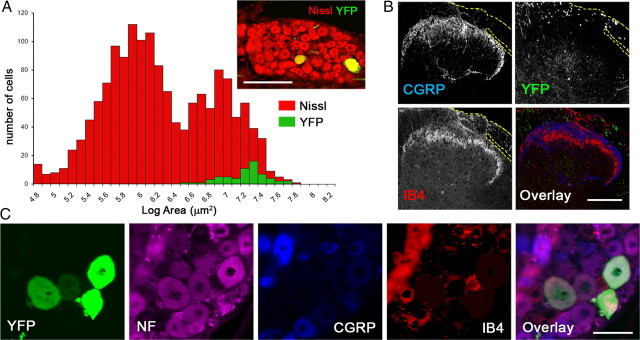

YFP-labeled DRG neurons are large and neurofilament positive

To monitor DR regeneration directly in living mice, we used the H line of thy1-YFP mice (thy1-YFPH), which expresses high levels of YFP in subsets of neurons, including sensory neurons in DRGs (Feng et al., 2000). Because DRG neurons are heterogeneous, we first characterized YFP-labeled neurons in DRG of thy1-YFPH mice. YFP+ neurons were large, with an average size of 1244.7 μm2 (Fig. 1A) (n = 66, compared to the mean size of 594 μm2 of 1523 Nissl-stained neurons). As expected for large DRG neurons (Ruscheweyh et al., 2007), YFP+ neurons were neurofilament+ but CGRP-negative (CGRP−) and IB4− (Fig. 1C). Additional analysis of superficial layers of the dorsal horn in thy1-YFPH mice revealed little YFP fluorescence in lamina II, where CGRP+ and IB4+ innervation is abundant (Fig. 1B). We also observed that CGRP+ axons were not labeled in the line 16 thy1-YFP (thy1-YFP16) mice, which were thought to express YFPs in nearly all neurons (data not shown) (cf. Fig. 10). These results are consistent with an earlier characterization of the M line thy1-YFP mice (thy1-YFPM), in which fewer neurons are labeled than in the H line (Kerschensteiner et al., 2005). Large, neurofilament+ neurons are myelinated and their central axon processes are thought to regenerate more poorly than those of small-diameter, nonmyelinated neurons (Tessler et al., 1988; Guseva and Chelyshev, 2006). Thus, thy1-YFPH mice provide a unique opportunity to study in vivo the axon regeneration of sensory neurons whose regeneration potential may be particularly weak.

Figure 1.

YFP-labeled DRG neurons are large and neurofilament positive. A, Size distribution of YFP+ L5 DRG neurons (green) in Thy1-YFPH mice, superimposed on the entire population, labeled with a fluorescent Nissl stain (red, inset). YFP+ neurons are large. B, Superficial layers of the dorsal horn of a Thy1-YFPH mouse, exhibiting little YFP fluorescence in lamina II, where CGRP+ and IB4+ innervation is abundant. Yellow dotted lines denote dorsal roots. C, Four-color immunolabeling of a DRG cross section illustrating expression of neurofilament (magenta) but not CGRP (blue) or IB4 (red) in YFP+ DRG neurons (green) in Thy1-YFPH mice. Scale bars: A, 200 μm; B, 200 μm; C, 50 μm.

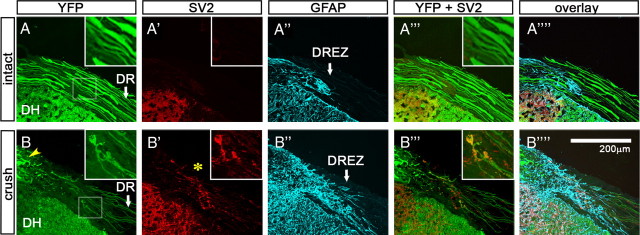

Figure 10.

Intense immunoreactivity of synapse markers associated with axon tips and shafts at the DREZ. Cross sections of the cervical roots of intact (A–A″″) and crushed (B–B″″) Thy1-YFP16 mice were immunolabeled with antibodies against SV2 (red) and GFAP (blue). The cervical roots (C3–C5) of the injured mouse were crushed peripherally 20 d previously. A, In the intact Thy1-YFP16 mouse, all of the large-diameter DR axons were labeled. DR, Dorsal root; DH, dorsal horn. A′, SV2 immunoreactivity is not observed along the DR or at the DREZ. A″, GFAP-labeled astrocytes denote the glial interface at the DREZ (arrow). No SV2 (A′) or synaptotagmin (data not shown) immunoreactivity is present in the CNS territory of the DREZ (A″″–A″″). Insets magnify an area of the DREZ. B, In the injured mouse, numerous regenerating axons stop at the DREZ. The inset is a magnified view of an area of the DREZ showing two axons and their tips. Yellow arrowhead indicates debris of degenerating YFP+ axons. B′, Intense SV2 immunoreactivity is present at the DREZ where axons terminate. The inset illustrates intense SV2 immunoreactivity associated with the two axon tips and shafts. B″, Astrocytes invade further into the periphery in the injured mouse. Note that SV2 immunoreactivity associated with the axon tips and shafts is present in the CNS territory as marked by GFAP-labeled astrocytes (B″″, B″″).

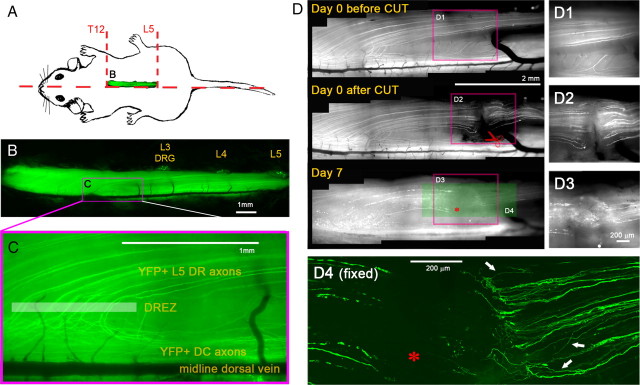

Axons turn around and fail to elongate through a transection injury

While optimizing the in vivo imaging techniques for DR regeneration, we learned that regeneration of individual DR axons is better imaged in lumbar than in cervical spinal cord of thy1-YFPH mice (A. Skuba, T. Mimes, and Y. J. Son, unpublished observations). In our typical preparation, we performed a right-sided laminectomy (Fig. 2A) (T12–L5) to partially expose the L5 root and the DREZ where these processes enter the spinal cord (Fig. 2B,C; highlighted box in Fig. 2C approximates the DREZ). Superficially positioned YFP+ axons in the medial portion of the L5 root (3–10 axons) run parallel to the midline dorsal vein, curve perpendicularly to enter the DREZ, and then bifurcate within the spinal cord, with one branch that enters the dorsal column (DC) and another that enters the gray matter (Fig. 2C). This stereotypical trajectory helped us to follow regeneration of several identified axons simultaneously and repeatedly over time in vivo. It also permitted us to identify reliably the location of the DREZ in living spinal cord.

Figure 2.

Axons fail to elongate through a transection injury. A, Schematic illustration of a right-sided laminectomy (T12–L5) to partially expose the L5 root. B, Low-magnification fluorescence view of the exposed spinal cord of a living Thy1-YFPH mouse. The laminectomy extends laterally to partially expose L3, L4, and L5 DRGs and medially to expose the midline dorsal vein. C, High-magnification fluorescence view of the area where L5 DR axons enter the spinal cord. Superficially positioned YFP+ axons run parallel to the midline dorsal vein, curve perpendicularly to enter the DREZ, and then bifurcate within the spinal cord. Highlighted box approximates DREZ. D, Repeated imaging of L5 DR axons for 7 d after root transection. Axons in L5 root were cut near the L3 DRG (red scissors), ∼3 mm from the DREZ, and imaged on day 0, day 3 (not shown), and day 7. The area of the root transection (red boxes) is magnified in right panels (D1–D3). D1, Before the transection. A few superficial YFP+ axons are visible. D2, After the transection. The medial portion of the L5 root was completely cut with spring scissors, and the proximal and distal ends were then closely reapposed. D3, Seven days after the transection. The transection site is filled with ∼500 μm collagenous scar tissue. No axons cross it. D4, A high-magnification confocal view of the area prepared after sacrificing the mouse on day 7. YFP+ axons located deeper in the root than those imaged in vivo also failed to regenerate across the transection site (asterisks). Instead, they turned around (arrows) and extended back along the proximal axons. Note that all the fluorescence in the stump beyond the cut (i.e., left of the asterisk) is due to fragments of degenerating axons that retained YFP.

We first monitored DR axons after complete transection. The medial portion of the L5 root was cut near the L3 DRG, ∼3 mm from the DREZ, using a fine-spring scissors (Fig. 2D2). After lifting the proximal stump to confirm that the DR had been completely transected, we closely apposed the cut ends of the proximal and distal stumps and then examined axons on both sides of the transection 3 and 7 d after injury. Even 7 d after the cut, no YFP+ axons from the proximal stump extended across the transection site (Fig. 2D3) (n = 4 mice). The two ends were separated by ∼500 μm of collagenous scar tissue, which seemed to prevent proximal axons from penetrating this region. After the mice were killed, we used confocal imaging to confirm that YFP+ axons located deeper in the root than those that we imaged in vivo also failed to regenerate across the injury site (Fig. 2D4). Importantly, however, few if any neurites formed bulblike endings or terminated abruptly. Instead, they turned around at the transection site and extended back along the proximal axons (e.g., arrows in Fig. 2D4) (n > 95 axons, 3 mice).

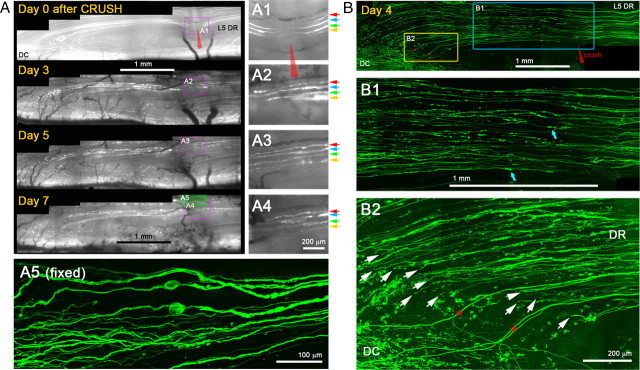

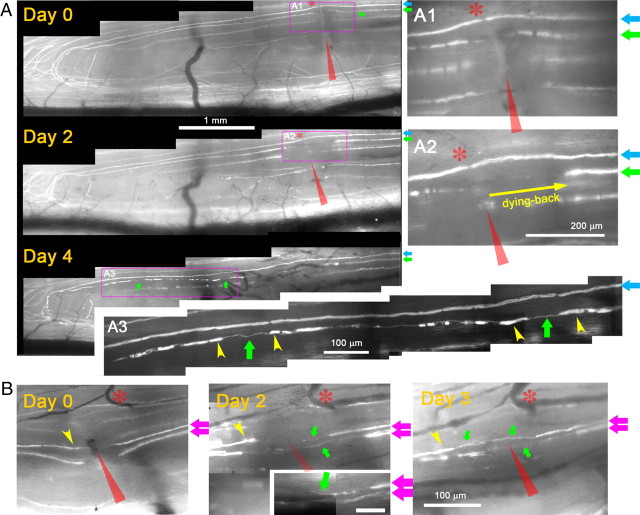

Axons elongate through a crush injury with little variability

Next, we monitored YFP+ axons every 24–48 h for 7 d after a crush injury (Fig. 3). We crushed the medial portion of the L5 root with a fine forceps (Fig. 3A1). The next day we observed dying-back degeneration of proximal stump axons (data not shown, e.g., Fig. 4A2) and fragmentation/degeneration of the same axons distal to the crush (e.g., yellow arrowheads in Fig. 4A3) (cf. Kerschensteiner et al., 2005), which confirmed that axons had been appropriately damaged. We applied several additional criteria for unambiguously distinguishing regenerating axons from axons that had been spared or recovered from the injury. These included the following: (1) in regenerating axons, there was expansion of the nonfluorescent portion of the YFP+ axon at the crush site due to proximal and distal degeneration (in contrast to narrowing of the unlabeled gap due to fluorescent cytoplasm refilling the crush site if axons survived the injury); (2) regenerating axons were much thinner, less brightly fluorescent, and more undulating than axons that survived the injury; (3) regenerating neurites were thinner and more dimly fluorescent than the degenerating fluorescent fragments of axons through which they extended; (4) in contrast to surviving or spared axons, regenerating axons stopped at the DREZ; and (5) in contrast to surviving or spared axons, regenerating axons did not exhibit nodes of Ranvier.

Figure 3.

Axons elongate through a crush injury with little variability. A, Repeated imaging of L5 DR axons for 7 d after root crush. The medial portion of the L5 root was crushed with a fine forceps (red arrowhead) and imaged on days 0, 3, 5, and 7 after the crush. The area of the crush is magnified in the right panels (A1–A4). A1, Immediately after crush. Four injured YFP+ axons are shown (colored arrows). A2, Three days after the crush. All four axons could be reidentified. Each axon extends a single neurite that crosses the site of crush. A3, A4, Five and seven days after crush. Neurites remain stable and there is no additional growth from these or other proximal axons. Axon swellings are occasionally observed (e.g., A4; axon marked by blue arrows). A5, High-magnification confocal view of the area prepared after sacrificing the mouse on day 7. YFP+ axons located deeper in the root also regenerate across the crush site. B, Confocal analysis of the regeneration after a crush injury in another Thy1-YFPH mouse that did not receive in vivo imaging. The L5 root was crushed at the usual location (red arrowhead); 4 d later, the spinal cord was prepared in whole mounts and analyzed by high-resolution confocal microscopy. The area near the crush injury (blue box) and the DREZ (yellow box) on day 4 are magnified in B1 and B2, respectively. B1, Consistent with in vivo imaging observations, almost all YFP+ axons extended a single neurite that crossed the crush site and grew further without stopping. Blue arrows point to degenerating axon fragments. B2, Almost all axons reached the DREZ and terminated at a location similar to that of single axons (arrows). Few axons turned around (e.g., arrowhead), further evidence of the consistency of the axon response to crush injury. DC, Dorsal column; DR, dorsal root. Red stars indicate uninjured axons. Because their proximal portion was located laterally, they escaped crush of the medial portion of the L5 root.

Figure 4.

Axons elongate >1.5 mm/d along preexisting endoneurial tubes. A, Repeated imaging of an identified axon for 4 d after root crush. On day 0, a Thy1-YFPH mouse with only a few superficial YFP+ axons underwent crush of the most medial portion of the L5 root (red arrowheads) to minimize the number of damaged axons. A1, Magnified view of the crush site immediately after injury. Two superficial axons are shown; the axon marked by a blue arrow (blue axon) was stretched but survived the injury, whereas the axon marked by a green arrow (green axon) was damaged. On day 2, degeneration of both proximal and distal tips confirmed apparent damage of the green axon by the crush. A2, Magnified view of the crush site. Yellow arrow denotes dying-back degeneration of the green axon. Note that no neurite has yet been formed by the green axon. On day 4, the green axon has extended ∼3 mm, and its tip has reached the DREZ. A3, Magnified view of the green axon near the DREZ, illustrating its growth along the fluorescent fragments of degenerating distal axons (yellow arrowheads: i.e., endoneurial tube trajectory). B, Examples of newly formed neurites on proximal stump axons imaged 2 d after injury. Day 0, Magnified view of the crush site immediately after injury showing two crushed axons (pink arrows). Day 2, Both axons extended short neurites (green arrows) that have not yet reached the distal stump axons (e.g., yellow arrowhead). These neurites have slender growing tips (green arrow, inset). Day 3, Both neurites extended through the degenerating distal axons. Asterisks in A1 and A2 indicate a node of Ranvier on the blue axon that served as a landmark. Blood vessels served as a landmark in B. Red arrowheads indicate the site of crush.

In contrast to the transection injury, almost all crushed YFP+ axons extended a single neurite that grew across the site of injury by 3 d (Fig. 3A2) (n > 25 axons, 5 mice) without forming additional branches (Fig. 3A3,A4). Confocal analysis 7 d after injury confirmed that almost all YFP+ axons located deep in the DR also grew through the crush site (Fig. 3A5).

To exclude the possibility that these observations were due to imaging-associated artifacts, we examined mice 4 d after crush injury that we had not previously imaged in vivo (Fig. 3B). Consistent with in vivo imaging observations, almost all YFP+ axons extended a single neurite through the crush site and grew until reaching the DREZ (Fig. 3B1) (n > 85 axons, 2 mice). Notably, by 4 d, almost all of the axons had already arrived at the DREZ, ∼3 mm beyond the injury site, and terminated at a similar location (Fig. 3B2, arrows). We observed few axons turning around, further evidence of the consistency of the axon response to crush injury. Thus, most, and perhaps all, YFP+ sensory axons, which have previously been thought to have a relatively weak regenerative capacity, can nevertheless regenerate across a crush site, extend within the PNS, and arrive at the DREZ.

Axons grow >1.5 mm/d

We next investigated in vivo how quickly YFP+ DR axons regenerated along the root (Fig. 4). This process was difficult to accomplish, however, because fragments of degenerating YFP+ axons (e.g., yellow arrowheads in Fig. 4A3) retained fluorescence for 7–10 d and obscured the leading tips of regenerating YFP+ axons. To circumvent the problem, we minimized the number of damaged YFP+ axons by crushing only the most medial portion of the L5 root (Fig. 4A1). This strategy enabled us to crush only one or two YFP+ axons and follow their regeneration with little residual YFP fluorescence. The crush was made at the usual location, ∼3 mm away from the DREZ, and the crushed axons were imaged daily. Typically, the proximal tips of the crushed axons degenerated for 2 d after injury (Fig. 4A2) (e.g., an axon marked by green arrow) and then extended a short neurite, which, by day 4, had grown ∼3 mm along the fluorescent fragments of degenerating axons (i.e., endoneurial tubes marked by yellow arrowheads; Fig. 4A3) and arrived at the DREZ (Fig. 4A3). We also observed short neurites extending from some of the proximal axons imaged 2 d after injury (Fig. 4B, green arrows). Thus, YFP+ axons elongated at a rate of >1.5 mm/d along their original endoneurial tube trajectory. These observations are consistent with confocal analysis of mice that we did not image in vivo (cf. Fig. 3B), and demonstrate that large-diameter axons grow well along the dorsal root, with little variability.

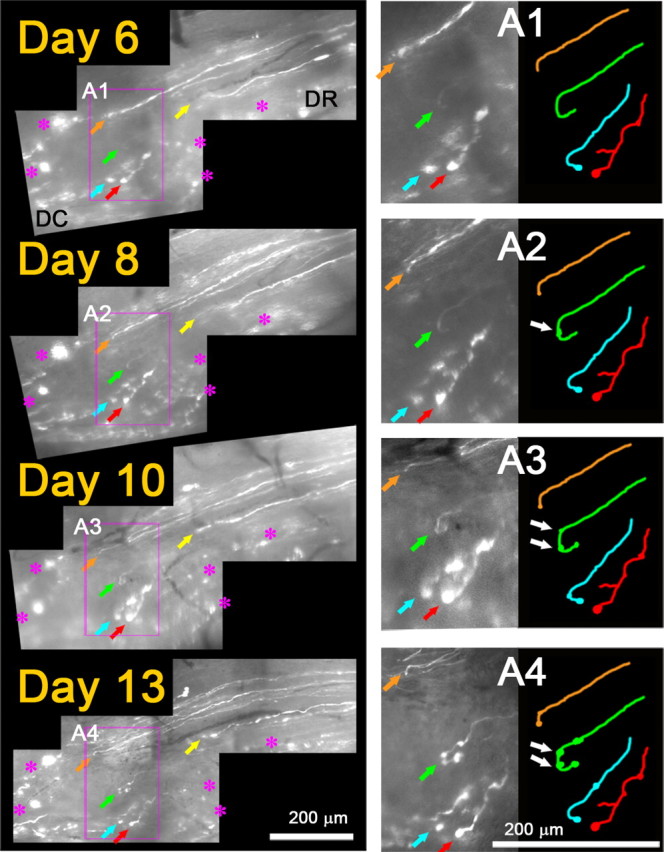

Rapid immobilization of axons entering the DREZ

To determine the behavior of axons at the PNS/CNS border, we continued imaging axons beyond 4 d after crush, when they arrive at the DREZ. Because more degenerating fluorescent axon fragments (i.e., residual YFP fluorescence) disappeared over the next few days, we resumed imaging 6 or 7 d after injury when the growth tips of regenerating axons were fairly easy to recognize. In several mice with L5 root crush, we were able to identify a number of axon tips arriving at the DREZ on day 6 or 7 (n = > 40 axons, 6 mice) and relocate them again in subsequent imaging sessions over 2 weeks after crush (Fig. 5). Unexpectedly, the leading tips of these axons did not continue to grow forward, retract, or turn around but were completely immobile; they remained in the same location in subsequent imaging sessions (i.e., as identified by the relative location with respect to adjacent axons or landmarks such as blood vessels and fluorescent debris). Notably, their appearance also did not change except that swellings formed on the tips or shafts of some axons (Fig. 5, white arrows).

Figure 5.

Regenerating axons are rapidly immobilized at the DREZ. Repeated imaging of axon tips at the DREZ 6–13 d after root crush. On day 0 (data not shown), the L5 root was crushed at the usual site, ∼3 mm away from the DREZ. On day 6, tips of five regenerating axons are observed at the DREZ (colored arrows). DC, Dorsal column; DR, dorsal root. Magenta asterisks denote fluorescent debris of degenerating old axons that served as landmarks. Note that the location of an axon tip relative to other axon tips and landmarks remained unchanged in subsequent imaging sessions on days 8, 10, and 13, indicating that the axons were immobilized after entering the DREZ. A1–A4, Magnified view of the area outlined by magenta boxes showing tips of four axons. They did not grow, retract, or turn around and remained in the same location in subsequent imaging sessions. Their appearance also was unchanged except for swellings that developed on the tips or shafts of some axons (e.g., white arrows in A2–A4).

We occasionally observed slowly growing and retracting axons (Fig. 6). Close observation, however, indicated that this growth was short neuritic sprouting extending from (Fig. 6A5), and then being reabsorbed by (Fig. 6A6), axon tips that remained stationary and developed swollen endings over time (Fig. 6A4–A6, pink arrows). On the last day of imaging, we killed the mouse, analyzed the same axon endings with high-resolution confocal microscopy, and confirmed that no growth tip structures had been missed due to poor resolution of our live imaging setup (data not shown) (compare Fig. 8, day 20). The apparent mobility of these axons at the DREZ was therefore due to fruitless sprouting of immobilized axon tips. Collectively, considering that axons arrive at the DREZ as early as 4 d after crush injury (compare Fig. 4), these observations demonstrate that axons are immobilized surprisingly quickly after arriving at the DREZ. It is also notable that, in contrast to axons at the site of a transection injury (Fig. 2D), axons arriving at the DREZ after crush injury (Fig. 4) rarely turned around along the dorsal root even though this pathway contains growth-promoting Schwann cells.

Figure 6.

Immobilized axon endings at the DREZ extend and retract a sprout. Shown is continued imaging of the mouse shown in Figure 4, 7–11 d after L5 root crush. On day 7, the tip of the green axon (magenta arrows) is at the same location as on day 4 (cf. Fig. 4). The blue axon that was stretched on day 0 has degenerated. Red asterisks indicate axon debris, a landmark, that remained stable during the imaging sessions. Note that the relative distance between the tip of the green axon and the debris remained the same on subsequent imaging sessions on days 9 and 11. A4, Magnified view of the axon tip on day 7. A fine neurite extends from the slightly swollen tip (magenta arrow). A5, Two days later on day 9, the neurite has elongated ∼50 μm; the axon tip remains at the same location and is more swollen. A6, Two days later on day 11, the neurite appears to have absorbed into the tip, which remains immobilized at the same location. Thus, the apparent mobility of this axon at the DREZ was due to fruitless sprouting of a stabilized axon tip.

Figure 8.

Axons are rapidly immobilized at the DREZ even after conditioning lesion. Repeated imaging of conditioning lesioned DR axons over 20 d after L5 root crush. Day −10, A schematic drawing illustrating a conditioning lesion of the ipsilateral sciatic nerve 10 d before DR crush. Day 0, Immediately after the root crush, 10 d after conditioning lesion. L5 root was crushed at the usual location (red arrowhead). Three crushed axons are shown in the large yellow inset box that magnifies the superficial site of crush (small yellow box). Day 2, All three axons have already extended neurites across the crush site, illustrating enhanced growth within the root due to a conditioning lesion. Magenta box, An area of the DREZ where several axons were monitored in subsequent imaging sessions, presented in magnified views in the right panels. Day 4, No axons regenerated through the DREZ (data not shown). The tips of these axons remain in the same location and have a similar appearance in subsequent imaging sessions on days 7, 9, 13, 15, and 20. Positions of an axon tip relative to other axon tips and landmarks were used to determine axon motility between imaging sessions. Yellow arrowhead denotes the tip of an axon with a particularly large increase in size over time. These axons were found again after the mouse was killed, and high-resolution confocal microscopy confirmed the location and appearance of the axon tips [day 20 (fixed)].

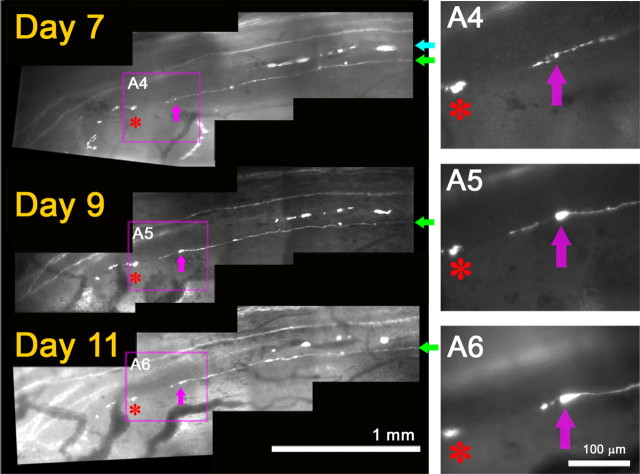

Chronic immobilization of axon endings at the DREZ

We also observed the long-term response of DR axons stopped at the DREZ in mice whose L5 root had been crushed 4 months previously (Fig. 7) (n = 15 axons, 2 mice). When we initiated imaging at 128 d after the crush, we observed several superficially positioned YFP+ axons and their tips at the DREZ (Fig. 7A, colored arrows). In subsequent imaging sessions at days 131 and 140 after crush, these axons were not motile but remained in the same place and looked unchanged, demonstrating chronic immobilization or stability. We also analyzed a mouse whose L5 root had been crushed 4 months previously but had not been studied with in vivo imaging (Fig. 7B). Confocal analysis revealed axon profiles at the DREZ that appeared similar to those observed within the first week after crush (compare Fig. 3B2): almost none of the YFP+ axons turned around; instead, almost all of them terminated as single processes at a similar location at the DREZ. Axon swellings, similar in appearance to synaptic varicosities, were also frequently observed on axon shafts (Fig. 7B, yellow arrowheads). These observations show that axons quickly immobilized on entering the DREZ remained completely immobile and stable for long periods despite the absence of target innervation.

Figure 7.

Axons are chronically immobilized at the DREZ. A, Repeated imaging of axons crushed 4 months previously. L5 root of a Thy1-YFPH mouse was crushed (red arrow) and imaged on days 1, 128, 131, and 140 following injury. On day 1, the root crush is indicated by degeneration of proximal and distal axon stumps at the injury site. On day 128, several axons are located at the DREZ outlined by a magenta box. A1, Magnified view of the DREZ area showing at least five axons and their tips (colored arrows). A2, Magnified view of the yellow boxed area in A1, showing an axon and its tip marked by red arrows. The location and appearance of these axons and their tips remained unchanged on subsequent imaging sessions on days 131 and 140. A3, Magnified view of the axon in A2 on day 131, illustrating its chronic stability. The day 140 image is a confocal view of the area prepared in a fixed whole mount. B, Confocal analysis of a different mouse that was not imaged in vivo. Top, L5 root was crushed at the usual location (red arrowhead) and, 4 months later, the spinal cord was analyzed in a whole-mount preparation. White dotted line, Location of axon tips at the DREZ. Asterisks, Intact axons that were uninjured because of their location lateral to the crush site. Bottom panel, Magnified view of the magenta-boxed area. Almost no axons turned around, and their tips (white arrows) were found at a location similar to those in mice imaged in vivo on day 140 (cf. Fig. 7A) and on day 4 (cf. Fig. 3B2) after root crush, further evidence of the chronic stability of axons at the DREZ. Yellow arrowheads, Swellings formed on axon shafts.

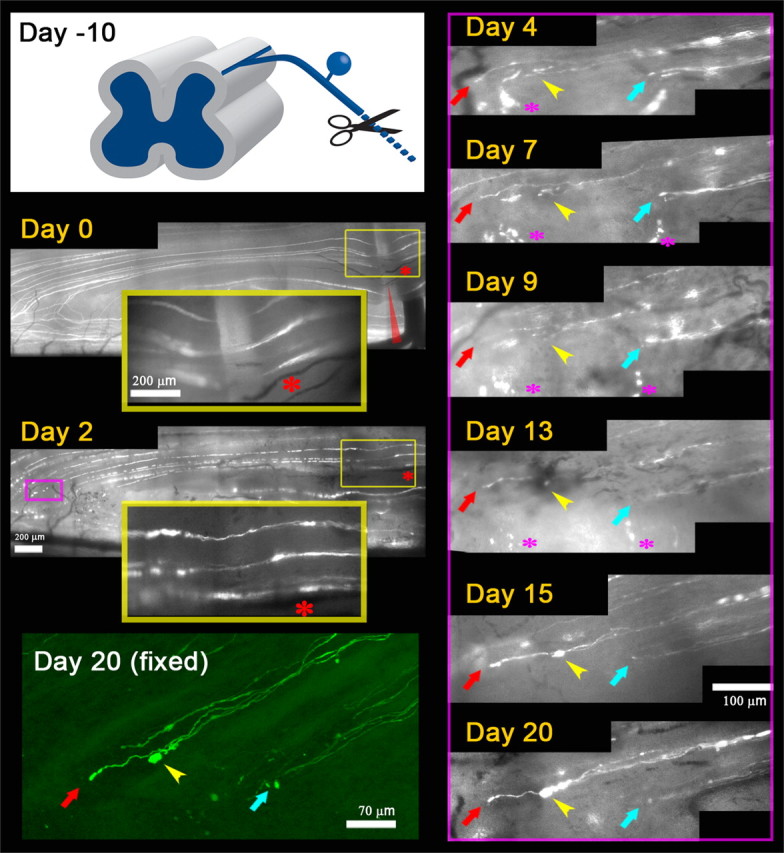

Rapid immobilization of axons at the DREZ even after a conditioning lesion

Next, we asked whether axons became motile at the DREZ following a conditioning lesion of peripheral processes that enhances the growth potential of DRG neurons (Chong et al., 1999). To this end, we crushed sciatic nerves in the ipsilateral leg 10 d before crushing the L5 root at the usual location (Fig. 8) (n = 6 mice). We then imaged these mice in vivo every 2 or 3 d over 3 weeks, and monitored regeneration of identified axons at the crush site, along the root, and at the DREZ. We found that most YFP+ axons had already extended through the crush site 2 d after crush (Fig. 8, day 2) (95%, n = 15), 1 d faster than nonconditioned axons. In addition, axons frequently extended more than one neurite, further illustrating the enhanced growth within the root due to a conditioning lesion. However, we observed no axons that had regenerated through the DREZ at 4 d after crush (Fig. 8, day 4) (n > 85 axon tips located at the DREZ). Instead, like nonconditioned axons at 4 d after crush (compare Figs. 3B, 4), these conditioned axons did not turn around upon arriving at the DREZ but terminated as single processes at a similar location at the DREZ. In subsequent imaging sessions over the next 3 weeks, they did not grow forward or retract but remained immobile (Fig. 8). The only noticeable change was the swelling of the tips and shafts of some axons (Fig. 8, yellow arrowheads). Thus, even conditioned axons with enhanced peripheral growth were quickly immobilized or stabilized at the DREZ.

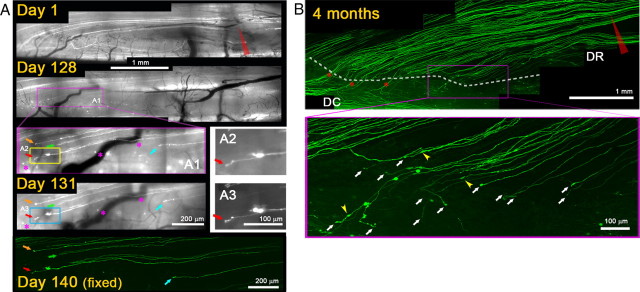

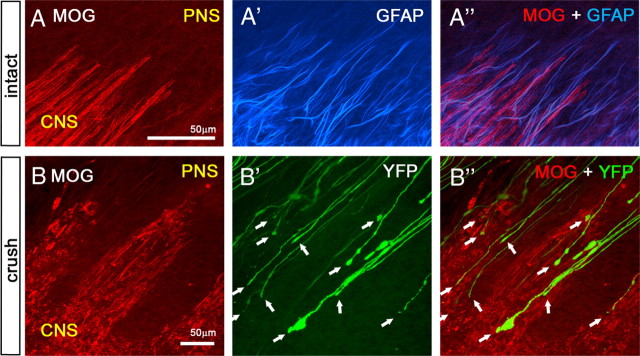

Axons do not stop upon encountering astrocytes

At the DREZ, both astrocytes and oligodendrocytes are juxtaposed to PNS Schwann cells. Following DR injury, astrocytes proliferate and hypertrophy, occupy the DREZ, and are the first cells encountered by axons regenerating from the periphery (Bignami et al., 1984; Fraher et al., 2002). Stalled axons at the DREZ were observed to contact astrocytes (Carlstedt, 1985; Fraher, 2000), and reactive astrocytes were thought to form a primary regenerative barrier at the DREZ. We were intrigued by the unexpectedly rapid and long-lasting immobilization or stabilization of axons arriving at the DREZ and wondered whether axons become immobilized as they encounter astrocytes. To this end, we developed a unique immunostaining protocol that permitted antibodies to penetrate deep into the surface of spinal cords prepared in whole mount (see Materials and Methods). This method allowed us not only to identify axons that we imaged in vivo but also to label simultaneously oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and Schwann cells that were near or directly associated with axons at DREZ (Fig. 9A,B).

Figure 9.

Axons terminate in CNS territory containing oligodendrocytes. A–A″, Low-magnification confocal view of the glial interface at the DREZ in an intact Thy1-YFPH animal. Oligodendrocytes (A, red) and astrocytes (A′, blue) were labeled with MOG and GFAP antibodies, respectively, in a whole-mount preparation. Note that astrocytes extend further into the periphery than oligodendrocytes even in intact, noninjured DREZ (A″). Axons (green) were omitted. B–B″, Confocal view of the glial interface at the injured DREZ. The L5 root was crushed 2 weeks previously. Oligodendrocytes are degenerating (B, red), whereas astrocytes invade further into the PNS (data not shown) (cf. Fig. 10A″,B″). Axons (B′, YFP) do not stop when they encounter astrocytic processes in the interface (data not shown) but terminate deeper in CNS territory containing oligodendrocytes (B″, white arrows).

We crushed L5 roots (n = 2 mice), monitored them for 2 weeks in vivo, and confirmed that most axons in these mice terminated in the usual location at the DREZ 4 d after crush, and then remained immobile (data not shown). Subsequently, oligodendrocytes (Fig. 9B) and astrocytes (data not shown) were immunolabeled in whole mounts and their relationships with the axons imaged in vivo were analyzed with high-resolution confocal microscopy. As expected (Fraher, 1999; Fraher et al., 2002), astrocytic processes extended further into the periphery than the oligodendrocytes, even in the intact, noninjured DREZ (Fig. 9A–A″) and invaded the PNS even more extensively after injury (data not shown) (compare Fig. 10A″,B″). We found that axons did not stop when they encountered astrocytic processes at the astrocyte-PNS interface but extended along them and terminated deeper in the CNS territory containing degenerating oligodendrocytes (Fig. 9B″) (>95%, n = 46 axon, 2 mice).

Presynaptic differentiation of axons at the DREZ

The rapid immobilization and subsequent swellings often formed on axon shafts and tips resembled the synaptogenic process and prompted us to test whether DR axons form synapses as they enter the CNS territory of the DREZ. We first immunolabeled cryostat sections of the DREZ where many stalled axons were observed (Fig. 10B–B″″), with synapse markers such as SV2 or synaptotagmin, together with a GFAP antibody to mark CNS territory. Whereas no SV2 or synaptotagmin immunoreactivity existed at the DREZ of uninjured mice (Fig. 10A′), numerous, intense immunopositive profiles were observed in the CNS territory of the DREZ of injured mice (Fig. 10B″, asterisk), and they colocalized with tips or adjacent shafts of stalled YFP+ axons (Fig. 10B‴, inset).

We next performed an ultrastructural analysis of axons that had stopped at the DREZ (Fig. 11). To target our analysis to the CNS territory of the DREZ where axons had stopped (Fig. 11B, yellow arrowheads), we placed DiI crystals (Fig. 11A, white arrows) at the completion of in vivo imaging at 13 d after the L5 root crush. DiI crystals were then photoconverted and used as landmarks to relocate the area with electron microscopy. This strategy allowed us to observe abundant axonal profiles at the DREZ, embedded in non-neuronal profiles such as Schwann cells and astrocytes (Fig. 11C). These axonal profiles were filled with mitochondria and ∼40 nm vesicles but lacked the vacuoles and disorganized microtubules that are typical of dystrophic endings (Fig. 11D,E) (Ertürk et al., 2007). Moreover, vesicles and mitochondria were differentially distributed within the nerve-terminal-like profiles so that vesicles were highly clustered onto one side of electron-dense membranes that resembled active zones, and mitochondria were distributed toward the other side (Fig. 11D,E). Although features of presynaptic differentiation were apparent in these axonal profiles, no indications of differentiation such as postsynaptic densities were observed postsynaptically (Fig. 11D1,E1, red-pseudocolored), excluding the possibility that postsynaptic cells are adjacent axons. Together, these observations indicate that axons became immobilized at the DREZ by forming presynaptic endings on non-neuronal cellular elements as they entered the CNS territory of the DREZ.

Discussion

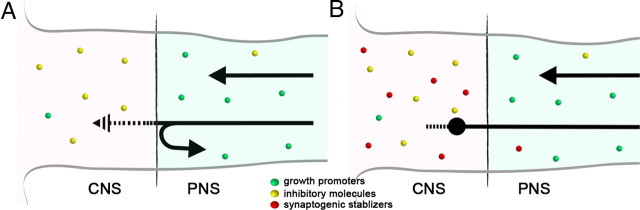

The generally accepted explanation for the regeneration failure at the DREZ is the combination of growth-inhibitory molecules and limited intrinsic growth potential. However, growth inhibitors that transiently collapse growth cones cannot account for the unexpectedly rapid and long-lasting immobilization of YFP+ axons that we observed in vivo even after a conditioning lesion. Furthermore, they rarely turned around at the DREZ and exhibited obvious features of presynaptic terminal endings. We propose that regeneration fails at the DREZ at least in part because axons are rapidly and chronically stabilized by induction of presynaptic differentiation (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of the current and proposed models of regeneration failure at the DREZ. A, The model that illustrates the prevailing view in the field. Black arrows represent regenerating DR axons. Sensory axons lack intrinsic growth potential but are capable of regenerating in the PNS due to abundant growth-promoting molecules (green circles). Their growth is prevented at the DREZ by growth inhibitors abundant in the CNS (yellow circles). According to this model, many axons must be repelled at the CNS/PNS interface (i.e., an arrow turned around to the PNS). Axons that invade CNS territory must be prompted to retract (i.e., patterned arrow) into the PNS by growth inhibitors that transiently collapse growth cones and then either attempt to reenter the CNS or grow further into the dorsal root. This model fails to explain rapid, long-lasting immobilization of most of the axons in the CNS territory of the DREZ. B, Proposed model. In addition to growth inhibitors (yellow circles), the CNS territory of the DREZ is enriched with synaptogenic molecules (red circles). Growth inhibitors alone are not powerful enough to repel most axons at the interface. Accordingly, most axons invade the CNS territory of the DREZ. They are, however, immobilized rapidly by synaptogenic activity that induces presynaptic differentiation (i.e., swollen axon ending). Both growth inhibitors and synaptogenic stabilizers prevent further growth or fruitless sprouting of the immobilized axon tips (i.e., patterned line protruded from the swollen axon ending).

Dorsal root regeneration in vivo

The present study is the first to apply in vivo imaging to monitor DR regeneration directly in living animals. Because we were concerned about the potential confounding effects of artifacts due to phototoxicity and multiple invasive surgical/anesthetic procedures, we performed extensive control experiments with mice that did not receive repetitive imaging or surgery. Several observations convinced us of the reliability of our techniques. First, our estimated axon elongation rate (>1.5 mm/d) was not slower (rather, it was slightly faster) than previous estimates based on conventional methods (Ramer et al., 2001a) (1 mm/d). Second, consistent with an earlier study (Ylera et al., 2009), we observed that conditioning lesions caused the injured dorsal roots to begin to grow earlier and to extend more neurites than after injury alone. Third, we observed little variability among YFP+ axons in initiation of growth, elongation along the root, or behavior at the DREZ.

Our observation that YFP+ axons fail to regenerate across the DREZ following a conditioning lesion is consistent with results from previous studies in rats, in which only minor effects were reported (Chong et al., 1999; Golding et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2007). It conflicts, however, with a recent report of significant regeneration in mice, which the authors attributed to species differences (Quaglia et al., 2008). It is possible that the capacity for growth varies greatly among different populations of DRG neurons in mice and that the latter study emphasized a different subpopulation, possibly small-diameter axons, which were not examined in the present in vivo imaging studies. Incomplete lesions or labeling artifacts may also be responsible (cf. Steward et al., 2007). A clear advantage of in vivo imaging was that it permitted us to evaluate immediately the extent of damage and to ascertain whether the lesion was complete or incomplete.

Axons are immobilized, rather than repelled, at the DREZ

Our observation that a conditioning lesion did not promote growth into the spinal cord agrees with the notion that the failure is likely due to growth-inhibitory molecules (Golding et al., 1999; Ramer et al., 2001b), such as CSPGs synthesized by astrocytes (Rhodes and Fawcett, 2004; Silver and Miller, 2004), Nogo, MAG, and OMgp present in myelin debris (Oertle and Schwab, 2003; Yiu and He, 2006), and semaphorins expressed by fibroblasts (Fawcett, 2006). However, these inhibitors act as repulsive cues that cause brief growth cone or filopodial collapse and allow axons to turn and grow away without a significant pause or long-term immobilization (Raper and Kapfhammer, 1990; Snow et al., 1990; Drescher et al., 1995; Li et al., 1996). Moreover, DRG axons extend despite growth cone collapse (Marsh and Letourneau, 1984; Jones et al., 2006; Jin et al., 2009). Some growing axons appeared to be trapped, forming dystrophic endings when exposed to a gradient of proteoglycans, but these axon endings remained extremely motile (Tom et al., 2004). Last, axons entering the DREZ in vivo are accompanied by Schwann cells, which would provide an alternative growth pathway (cf. Adcock et al., 2004) or constrain migration of axons into CNS territory (Grimpe et al., 2005). We therefore anticipated that axons entering the DREZ would be mobile and dynamic, frequently turning back to the PNS.

However, we found that YFP+ DR axons rarely turned around at the DREZ but terminated abruptly and remained completely immobile. In our injury paradigm, axons arrived at the DREZ 4 d after root crush. We often resumed imaging 6 or 7 d after crush due to residual fluorescence that obscured leading axon tips. It is unlikely, however, that we failed to observe local motility of axons that might be particularly substantial soon after arrival (i.e., 4–7 d after crush). Conditioning lesions led to earlier clearing of residual fluorescence (Skuba et al., unpublished observation), which permitted us to monitor axon tips 4–7 d after injury. These axon tips remained immobile at the same location during this period, without turning, retracting, or growing forward (Fig. 8). The large-diameter DR axons that we monitored in vivo are, therefore, unexpectedly and quickly immobilized as they enter the DREZ. Consistent with our in vivo results, neurites cultured on cryosections of the DREZ rarely turned around and did not collapse or retract, but became permanently immobile within 20 min (Golding et al., 1999).

Presynaptic differentiation at the DREZ

In vivo imaging enabled us to target our ultrastructural analysis specifically to the region of the DREZ where recently arrived axon tips were abundant. We were able to identify numerous axonal profiles within a few sections. They often looked “synapse-like” (data not shown), exhibiting abundant mitochondria and membranous vesicles, and resembled the structures called “synaptoids” (Carlstedt, 1985; Liuzzi and Lasek, 1987). However, these previously described “synapse-like” profiles lacked the characteristic features of synaptic differentiation. It is also known that mitochondria and vesicles are abundant even in nonsynaptic, dystrophic endings (Ertürk et al., 2007).

By contrast, the “synaptic” profiles that we encountered exhibited obvious features of presynaptic differentiation, including active zones, differential distribution of mitochondria and synaptic vesicles, and absence of microtubules and vacuoles. Moreover, they were intensely immunolabeled by synapse markers. These synaptic profiles were relatively small and did not seem to belong to the large, club-shaped bulbous endings that developed in some axons at the DREZ (e.g., Fig. 8, yellow arrowheads). They more likely represent those axon endings that did not increase in size or varicosities that we often observed on axon shafts near the tips (e.g., Fig. 9B′).

Earlier ultrastructural studies were performed relatively long after dorsal root injury: 6–9 months (Carlstedt, 1985) and 3 weeks to 3 months (Liuzzi and Lasek, 1987). These studies therefore could not determine whether axon endings became “synapse-like” as they entered the DREZ or whether they occasionally exhibited a synapse-like appearance after chronic remodeling. Thus, our studies provide novel and compelling evidence that axons become differentiated into presynaptic terminal endings immediately after entering the DREZ.

What causes presynaptic differentiation?

Synaptoids were speculated to be triggered by a physiological stop signal associated with reactive astrocytes (Liuzzi and Lasek, 1987). We also observed that portions of the axons exhibiting presynaptic profiles were in contact with filament-rich astrocytes (cf. Fig. 11D,E). Importantly, however, we did not observe abundant intermediate filaments in the postsynaptic cells that were in direct apposition to presynaptic profiles. This observation raises the possibility that nonastrocytic cell types, such as NG2+ cells, may provide the stabilizing activity or induce the presynaptic differentiation of regenerating axons at the DREZ. In support of this notion, (1) the postsynaptic cells did not exhibit postsynaptic densities, excluding that these profiles are axon–axon synapses (Bernstein and Bernstein, 1971); (2) axons did not stop when they encountered astrocytes at the CNS–PNS border but terminated deeper in the CNS territory; and (3) presynaptic active zones were thinner than at neuron–neuron synapses and resembled those reported at neuron–NG2+ cell synapses (Bergles et al., 2000; Lin and Bergles, 2004). Importantly, NG2+ cells are present at the DREZ (Zhang et al., 2001; Beggah et al., 2005) and stabilize dorsal column axons that macrophages cause to retract at the lesion site (Busch et al., 2010).

The role of NG2+ cells is speculative, however, and it is possible that reactive astrocytes are involved in the process. Recent studies revealed that astrocytes are capable of inducing and promoting synapse formation, presumably by releasing thrombospondins (Ullian et al., 2004; Wang and Bordey, 2008; Allen and Barres, 2009; Eroglu et al., 2009). An intriguing possibility, which we are currently testing, is that astrocytes prevent regeneration at the DREZ by mediating presynaptic differentiation between axons and NG2+ cells. Heparin sulfate proteoglycans may also be involved, since they trigger presynaptic assembly in the absence of specific target recognition (Lucido et al., 2009).

Useful for enhancing regeneration?

Efforts to overcome regeneration failure at the DREZ have included enhancing the regeneration capacity of sensory axons with neurotrophic factors and neutralizing growth inhibitors (Ramer et al., 2002; Steinmetz et al., 2005; Cafferty et al., 2007, 2010; Wang et al., 2008; Andrews et al., 2009; Harvey et al., 2009, 2010; Ma et al., 2010). The effectiveness of these efforts may have been limited because they did not treat the stabilizing activity at the DREZ. Conversely, even if axons are prevented from being stabilized at the DREZ, growth inhibitors might nevertheless inhibit regeneration into and across the DREZ. It is therefore reasonable to expect the best outcome from combinatorial strategies targeting both stabilizing and inhibitory activities. It is, however, worth pointing out that axons can regenerate along degenerating white matter (Davies et al., 1999; Kerschensteiner et al., 2005) and that simultaneous elimination of multiple inhibitory molecules alone did not promote intraspinal regeneration (Lee et al., 2010a,b) (but see Cafferty et al., 2010). It is tempting to speculate, therefore, that preventing presynaptic differentiation alone, particularly during the early stage of injury before full deposition of nonpermissive cues (Ramer et al., 2001b), might lead to significant regeneration after spinal root injury. It will also be important to determine whether such stabilizing activity restricts regeneration and/or anatomical plasticity elsewhere in the injured CNS.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NS062320 (Y.-J.S.) and World Class University program (R31-2008-000-100069-0) through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (Y.-J.S, J.K.H). We thank Rita Balice-Gordon, Wenbiao Gan, and Joshua Trachtenberg for advice on in vivo imaging; Theresa Connors and Amy Kim for technical assistance; and Marion Murray, Mickey Selzer, and Veronica Tom for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Adcock KH, Brown DJ, Shearer MC, Shewan D, Schachner M, Smith GM, Geller HM, Fawcett JW. Axon behaviour at Schwann cell–astrocyte boundaries: manipulation of axon signalling pathways and the neural adhesion molecule L1 can enable axons to cross. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1425–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ, Barres BA. Neuroscience: glia—more than just brain glue. Nature. 2009;457:675–677. doi: 10.1038/457675a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews MR, Czvitkovich S, Dassie E, Vogelaar CF, Faissner A, Blits B, Gage FH, ffrench-Constant C, Fawcett JW. α9 integrin promotes neurite outgrowth on tenascin-C and enhances sensory axon regeneration. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5546–5557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0759-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggah AT, Dours-Zimmermann MT, Barras FM, Brosius A, Zimmermann DR, Zurn AD. Lesion-induced differential expression and cell association of Neurocan, Brevican, Versican V1 and V2 in the mouse dorsal root entry zone. Neuroscience. 2005;133:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergles DE, Roberts JD, Somogyi P, Jahr CE. Glutamatergic synapses on oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus. Nature. 2000;405:187–191. doi: 10.1038/35012083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JJ, Bernstein ME. Axonal regeneration and formation of synapses proximal to the site of lesion following hemisection of the rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1971;30:336–351. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(71)80012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami A, Chi NH, Dahl D. Regenerating dorsal roots and the nerve entry zone: an immunofluorescence study with neurofilament and laminin antisera. Exp Neurol. 1984;85:426–436. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(84)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Horn KP, Cuascut FX, Hawthorne AL, Bai L, Miller RH, Silver J. Adult NG2+ cells are permissive to neurite outgrowth and stabilize sensory axons during macrophage-induced axonal dieback after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:255–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3705-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WB, Yang SH, Duffy PJ, Li S, Strittmatter SM. Functional axonal regeneration through astrocytic scar genetically modified to digest chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2176–2185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5176-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WB, Duffy P, Huebner E, Strittmatter SM. MAG and OMgp synergize with Nogo-A to restrict axonal growth and neurological recovery after spinal cord trauma. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6825–6837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6239-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Gao Y, Bryson JB, Hou J, Chaudhry N, Siddiq M, Martinez J, Spencer T, Carmel J, Hart RB, Filbin MT. The cytokine interleukin-6 is sufficient but not necessary to mimic the peripheral conditioning lesion effect on axonal growth. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5565–5573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0815-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlstedt T. Regenerating axons form nerve terminals at astrocytes. Brain Res. 1985;347:188–191. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong MS, Woolf CJ, Haque NS, Anderson PN. Axonal regeneration from injured dorsal roots into the spinal cord of adult rats. J Comp Neurol. 1999;410:42–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, Goucher DR, Doller C, Silver J. Robust regeneration of adult sensory axons in degenerating white matter of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5810–5822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05810.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher U, Kremoser C, Handwerker C, Löschinger J, Noda M, Bonhoeffer F. In vitro guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons by RAGS, a 25 kDa tectal protein related to ligands for Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1995;82:359–370. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu Ç, Allen NJ, Susman MW, O'Rourke NA, Park CY, Özkan E, Chakraborty C, Mulinyawe SB, Annis DS, Huberman AD, Green EM, Lawler J, Dolmetsch R, Garcia KC, Smith SJ, Luo ZD, Rosenthal A, Mosher DF, Barres BA. Gabapentin receptor [alpha]2[delta]-1 is a neuronal thrombospondin receptor responsible for excitatory CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2009;139:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk A, Hellal F, Enes J, Bradke F. Disorganized microtubules underlie the formation of retraction bulbs and the failure of axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9169–9180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0612-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JW. Overcoming inhibition in the damaged spinal cord. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:371–383. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, Keller-Peck C, Nguyen QT, Wallace M, Nerbonne JM, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraher JP. The transitional zone and CNS regeneration. J Anat. 1999;194:161–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19420161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraher JP. The transitional zone and CNS regeneration. J Anat. 2000;196:137–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraher J, Dockery P, O'Leary D, Mobarak M, Ramer M, Bishop T, Kozlova E, Priestley E, McMahon S, Aldskogius H. The dorsal root transitional zone model of CNS axon regeneration: morphological findings. J Anat. 2002;200:214. [Google Scholar]

- Golding JP, Bird C, McMahon S, Cohen J. Behaviour of DRG sensory neurites at the intact and injured adult rat dorsal root entry zone: postnatal neurites become paralysed, whilst injury improves the growth of embryonic neurites. Glia. 1999;26:309–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimpe B, Pressman Y, Lupa MD, Horn KP, Bunge MB, Silver J. The role of proteoglycans in Schwann cell/astrocyte interactions and in regeneration failure at PNS/CNS interfaces. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guseva D, Chelyshev Y. The plasticity of the DRG neurons belonging to different subpopulations after dorsal rhizotomy. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:1225–1234. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannila SS, Filbin MT. The role of cyclic AMP signaling in promoting axonal regeneration after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PA, Lee DH, Qian F, Weinreb PH, Frank E. Blockade of Nogo receptor ligands promotes functional regeneration of sensory axons after dorsal root crush. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6285–6295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5885-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P, Gong B, Rossomando AJ, Frank E. Topographically specific regeneration of sensory axons in the spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11585–11590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003287107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havton LA, Carlstedt T. Repair and rehabilitation of plexus and root avulsions in animal models and patients. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:570–574. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328331b63f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin LQ, Zhang G, Jamison C, Jr, Takano H, Haydon PG, Selzer ME. Axon regeneration in the absence of growth cones: acceleration by cyclic AMP. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:295–312. doi: 10.1002/cne.22057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SL, Selzer ME, Gallo G. Developmental regulation of sensory axon regeneration in the absence of growth cones. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:1630–1645. doi: 10.1002/neu.20309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerschensteiner M, Schwab ME, Lichtman JW, Misgeld T. In vivo imaging of axonal degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord. Nat Med. 2005;11:572–577. doi: 10.1038/nm1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Chow R, Xie F, Chow SY, Tolentino KE, Zheng B. Combined genetic attenuation of myelin and semaphorin-mediated growth inhibition is insufficient to promote serotonergic axon regeneration. J Neurosci. 2010a;30:10899–10904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2269-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Geoffroy CG, Chan AF, Tolentino KE, Crawford MJ, Leal MA, Kang B, Zheng B. Assessing spinal axon regeneration and sprouting in Nogo-, MAG-, and OMgp-deficient mice. Neuron. 2010b;66:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Shibata A, Li C, Braun PE, McKerracher L, Roder J, Kater SB, David S. Myelin-associated glycoprotein inhibits neurite/axon growth and causes growth cone collapse. J Neurosci Res. 1996;46:404–414. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961115)46:4<404::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Bergles DE. Synaptic signaling between GABAergic interneurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:24–32. doi: 10.1038/nn1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liuzzi FJ, Lasek RJ. Astrocytes block axonal regeneration in mammals by activating the physiological stop pathway. Science. 1987;237:642–645. doi: 10.1126/science.3603044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucido AL, Suarez Sanchez F, Thostrup P, Kwiatkowski AV, Leal-Ortiz S, Gopalakrishnan G, Liazoghli D, Belkaid W, Lennox RB, Grutter P, Garner CC, Colman DR. Rapid assembly of functional presynaptic boutons triggered by adhesive contacts. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12449–12466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1381-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TC, Campana A, Lange PS, Lee HH, Banerjee K, Bryson JB, Mahishi L, Alam S, Giger RJ, Barnes S, Morris SM, Jr, Willis DE, Twiss JL, Filbin MT, Ratan RR. A large-scale chemical screen for regulators of the arginase 1 promoter identifies the soy isoflavone daidzein as a clinically approved small molecule that can promote neuronal protection or regeneration via a cAMP-independent pathway. J Neurosci. 2010;30:739–748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5266-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L, Letourneau PC. Growth of neurites without filopodial or lamellipodial activity in the presence of cytochalasin B. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:2041–2047. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann S, Woolf CJ. Regeneration of dorsal column fibers into and beyond the lesion site following adult spinal cord injury. Neuron. 1999;23:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertle T, Schwab ME. Nogo and its paRTNers. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglia X, Beggah AT, Seidenbecher C, Zurn AD. Delayed priming promotes CNS regeneration post-rhizotomy in Neurocan and Brevican-deficient mice. Brain. 2008;131:240–249. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer MS, McMahon SB, Priestley JV. Axon regeneration across the dorsal root entry zone. Prog Brain Res. 2001a;132:621–639. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(01)32107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer MS, Duraisingam I, Priestley JV, McMahon SB. Two-tiered inhibition of axon regeneration at the dorsal root entry zone. J Neurosci. 2001b;21:2651–2660. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02651.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer MS, Bishop T, Dockery P, Mobarak MS, O'Leary D, Fraher JP, Priestley JV, McMahon SB. Neurotrophin-3-mediated regeneration and recovery of proprioception following dorsal rhizotomy. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;19:239–249. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y Cajal S. London: Oxford UP, Humphrey Milford; 1928. Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- Raper JA, Kapfhammer JP. The enrichment of a neuronal growth cone collapsing activity from embryonic chick brain. Neuron. 1990;4:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90440-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KE, Fawcett JW. Chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans: preventing plasticity or protecting the CNS? J Anat. 2004;204:33–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2004.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh R, Forsthuber L, Schoffnegger D, Sandkühler J. Modification of classical neurochemical markers in identified primary afferent neurons with Abeta-, Adelta-, and C-fibers after chronic constriction injury in mice. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:325–336. doi: 10.1002/cne.21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow DM, Lemmon V, Carrino DA, Caplan AI, Silver J. Sulfated proteoglycans in astroglial barriers inhibit neurite outgrowth in vitro. Exp Neurol. 1990;109:111–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(05)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow DM, Watanabe M, Letourneau PC, Silver J. A chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan may influence the direction of retinal ganglion cell outgrowth. Development. 1991;113:1473–1485. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz MP, Horn KP, Tom VJ, Miller JH, Busch SA, Nair D, Silver DJ, Silver J. Chronic enhancement of the intrinsic growth capacity of sensory neurons combined with the degradation of inhibitory proteoglycans allows functional regeneration of sensory axons through the dorsal root entry zone in the mammalian spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8066–8076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2111-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Zheng B, Banos K, Yee KM. Response to: Kim et al., “Axon regeneration in young adult mice lacking Nogo-A/B.” Neuron 38, 187–199. Neuron. 2007;54:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessler A, Himes BT, Houle J, Reier PJ. Regeneration of adult dorsal root axons into transplants of embryonic spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1988;270:537–548. doi: 10.1002/cne.902700407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom VJ, Steinmetz MP, Miller JH, Doller CM, Silver J. Studies on the development and behavior of the dystrophic growth cone, the hallmark of regeneration failure, in an in vitro model of the glial scar and after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6531–6539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0994-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullian EM, Christopherson KS, Barres BA. Role for glia in synaptogenesis. Glia. 2004;47:209–216. doi: 10.1002/glia.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Bordey A. The astrocyte odyssey. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:342–367. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, King T, Ossipov MH, Rossomando AJ, Vanderah TW, Harvey P, Cariani P, Frank E, Sah DW, Porreca F. Persistent restoration of sensory function by immediate or delayed systemic artemin after dorsal root injury. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:488–496. doi: 10.1038/nn2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MC, Potluri S, Wang X, Dentcheva E, Gautam D, Tessler A, Wess J, Rich MM, Son Y-J. Distinct muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes contribute to stability and growth, but not compensatory plasticity, of neuromuscular synapses. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14942–14955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2276-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]