Abstract

Objectives

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) facilitates multiple aspects of inflammatory arthritis, the pathogenesis of which is significantly contributed to by neutrophils. The effects of MIF on neutrophil recruitment are unknown. We investigated the contribution of MIF to the regulation of neutrophil chemotactic responses.

Methods

K/BxN serum transfer arthritis was induced in wild-type (WT), MIF -/-, and MCP1 (CCL2)-deficient mice, and in WT mice treated with anti-KC (CXCL1) mAb. In vivo leukocyte trafficking was examined using intravital microscopy, and in vitro neutrophil function was examined using migration chambers and MAP kinase activation.

Results

K/BxN serum transfer arthritis was markedly attenuated in MIF-/- mice, with reductions in clinical and histological severity as well as synovial expression of KC and IL-1. Arthritis was also reduced by anti-KC antibody treatment, but not in MCP-1-deficient mice. In vivo neutrophil recruitment responses to KC were reduced in MIF-/- mice. Similarly, MIF-/-neutrophils exhibited reduced in vitro chemotactic responses to KC, despite unaltered chemokine receptor expression. Reduced chemotactic responses in MIF-/- neutrophils were associated with reduced phosphorylation of p38 and ERK MAP kinases.

Conclusion

These data suggest MIF promotes neutrophil trafficking in inflammatory arthritis via facilitation of chemokine-induced migratory responses and MAP kinase activation. Therapeutic MIF inhibition could limit synovial neutrophil recruitment.

Neutrophils constitute the predominant leukocyte class in the synovial fluid of patients with inflammatory arthritides such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Human RA synovial fluid contains numerous active neutrophil chemoattractants, including chemokines such as GRO-alpha (CXCL1), that are likely to have key roles in pathological neutrophil recruitment during arthritis (1). Although the precise contribution of neutrophils to the complex biology of RA pathogenesis is unclear, numerous studies demonstrate the ability of neutrophils to influence the pathogenesis of in vivo models of arthritis. Neutrophil depletion is protective in rat adjuvant arthritis (2), and murine collagen-induced arthritis (3) models, while neutralization of neutrophil chemokines such as the murine CXCL1 homologue KC, RANTES (CCL5), or their receptors, results in protective effects in murine models of Lyme arthritis (4), antigen-induced arthritis (5-7), and rat adjuvant arthritis (8). These models are dependent on complex interactions of adaptive and effector immune responses, in which there may be multiple effects of neutrophils. The K/BxN serum transfer model of RA is also neutrophil-dependent (9), but does not depend on adaptive immune responses. Recently, upregulation of KC/CXCL1 and protective effects in mice deficient in its receptor, CXCR2, but not other chemokine receptors, was reported in the K/BxN serum transfer model (10). These findings indicate an unusually specific requirement for ligands of this chemokine receptor in this model of arthritis.

The recruitment of neutrophils requires a co-ordinated series of cellular events. After first undergoing rolling and arrest on locally activated vascular endothelial cells, adherent leukocytes migrate over the endothelial surface to find an optimal site for subsequent transmigration, and then migrate within the tissue towards chemotactic signals (11). Recent studies suggest leukocytes navigate this complex milieu using specific intracellular signalling molecules to prioritize chemotactic cues (12). Signals induced in response to ligation of G protein-coupled chemoattractant receptors and/or selectin ligands mediate integrin activation required for leukocyte arrest (13-15), and subsequent leukocyte chemotaxis involves the coordinated actions of multiple intracellular signalling molecules, including the MAP kinase (MAPK) pathways (16-19). Factors which affect leukocyte signalling pathway activation might therefore be expected to influence leukocyte responses during chemotaxis. A potential example of such a factor is macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF).

MIF is a pleiotropic pro-inflammatory protein which contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple inflammatory diseases (reviewed in Morand et al.(20)). Considerable evidence suggests a role for MIF in the pathogenesis of RA, including attenuation of disease parameters in animal models in the setting of MIF neutralisation or deficiency (21-24), overexpression of MIF in human RA (25), activating effects of MIF on human RA synovial fibroblasts (26-28), and association of a MIF overexpression gene polymorphism with the progression of erosions in RA (29). In addition to important effects of MIF on innate (30) and adaptive (24, 31) immune responses, a growing body of evidence also indicates that MIF promotes leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. Administration of exogenous MIF can induce leukocyte recruitment, via mechanisms including promotion of MCP-1 (CCL2) release from endothelial cells, and induction of leukocyte arrest and chemotaxis via interaction with CXCR2/4 (32, 33). Deficiency of endogenous MIF in vivo results in reduced leukocyte endothelial cell interactions under inflamed conditions (34), including the recruitment of synovial neutrophils during carrageenan-induced arthritis (35). Moreover, while direct administration of MIF increases monocyte recruitment, increased neutrophil recruitment is also observed (32), and several observations suggest an amplifying effect of MIF on neutrophil recruitment induced by other stimuli (36-41).

An emerging mechanism of action of MIF is its potentiation of MAP kinase activation in response to inflammatory stimuli including lipopolysaccharide (42), TNF and IL-1 (43), or during antigen-specific responses in T cells (44). The potentiating effect of MIF on MAP kinase activation, and the involvement of MAP kinase activation in neutrophil migratory responses to chemokines, lead to the hypothesis that MIF contributes to neutrophil trafficking responses via facilitation of chemokine-mediated neutrophil signalling. To investigate this, we studied the effects of MIF on neutrophil chemotactic responses in contexts in which the known effects of MIF on adaptive immune responses were irrelevant, namely in K/BxN serum transfer arthritis and in vitro. The results of these studies indicate a new function of MIF, the facilitation of chemokine-induced MAP kinase activation and migratory function in neutrophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Animal experiments were approved by the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee. MIF-/- and MCP-1(CCL2)-/- mice on the C57BL/6 background were used (45, 46). Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were used as controls.

K/BxN serum transfer arthritis: induction and disease assessment

Serum-induced arthritis was induced by intraperitoneal (IP) injections of mice with pooled K/BxN sera (days 0 & 2, either 8 μl/g body weight – high dose, or 4 μl/g – low dose) terminating on day 8 (47). In selected studies, anti-KC antibody (R&D Systems) or control Ig (both 50 μg, IP) were given every 2 days from day 0 and the final injection was given on day 6. Ankle thickness was measured with a caliper (Mitutoyo, Kawasaki-shi, Japan) and results expressed as mean change in ankle thickness in mm (thickness on day 8 – thickness on day 0) (48). Each limb was scored daily on a scale of 0 (no observable redness or swelling) to 5 (severe redness and swelling). The scores of 4 limbs were added together to obtain the clinical index (maximum score = 20). For histological assessment, ankle joint tissues were decalcified and processed. Four μm-thick sagittal ankle sections were stained with safranin-O and counter-stained with fast green/iron hematoxylin. Histological sections were scored 0-3 for each of four parameters: synovitis, joint space exudate, cartilage degradation, and bone damage, and total histological score calculated from the sum of these data as described elsewhere (44).

Whole joint extract processing

Whole joint extracts were processed using a previously described protocol (49). Briefly, whole ankle joints were frozen, pulverized with a mortar and pestle and tissue powder shredded using a QIAshredder kit following manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). RNA and protein were extracted using RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Samples were stored at -80 °C until required for ELISA and real-time PCR analysis.

Chemokine ELISA

ELISA was performed using a commercially available Quantikine kit (KC; R & D systems) or paired antibodies (MCP-1; R&D systems) following manufacturer's protocols. The detection limits were 15 pg/ml and 31 pg/ml for KC and MCP-1, respectively.

Real-time PCR

Complementary DNA was synthesized from total RNA (0.5 μg) using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random primers (Invitrogen). PCR amplification was performed on a LightCycler Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Research) using SYBR Green I (Invitrogen). The following primer-specific nucleotide sequences of murine IL-1 (5’-CCCAAGCAATACCCAAAGAA-3’ and 5’-CATCAGAGGCAAGGAGGAAA-3’), IL-1R (5’TGCGGGACACTAAGGAGAAA-3’ and 5’CTCTTCCCAATCCAGTTCCA-3’), TNF (5’-GCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGCTT-3’ and 5’-CACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGA-3’), IL-6 (5’-TTCCATCCAGTTGCCTTCTT-3’ and 5’-ATTTCCACGATTTCCCAGAG-3), MCP-1 (F5’-CCCCAAGAAGGAATGGGTCC-3’ and 5’GGTTGTGGAAAAGGTAGTGG-3’), and KC (5’GGGTGTTGTGCGAAAAGAAGTG-3’ and 5’-CAAAATGTCCAAGGGAAGCGTC-3’) were used. 18S (5’-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATTC-3’ and 5’-GCCTCACTAAACCATCCAATCG-3’) expression was used to normalize expression of respective mRNA species.

Intravital microscopy

Intravital microscopy of the cremaster muscle was performed as previously described (32). Briefly, the cremaster muscle of anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine) mice was exteriorised onto an optically-clear viewing pedestal and the cremasteric microcirculation was visualized using an intravital microscope (Axioplan 2 Imaging; Carl Zeiss, Australia). Images were visualized using a video camera and recorded on video-tape for subsequent playback analysis. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions (adhesion and emigration) were assessed as described (32). To assess neutrophil recruitment, the exteriorized cremaster muscle was superfused with recombinant KC (CXCL1) (Peprotech Inc (NJ, USA)) (10 nM, in superfusion buffer), and leukocyte interactions were assessed 0, 30 and 60 mins after commencing KC superfusion (50).

Neutrophil in vitro migration assays

To isolate mouse neutrophils, bone marrow was extracted from mouse femurs and tibias by lavage, and neutrophils purified by flow cytometry-based cell sorting. Neutrophils were gated by their characteristic size and granularity. The sorted population was > 90% neutrophils based on identification via high Gr1 and M1/70 staining. In vitro neutrophil migration assays were performed using a chemotaxis chamber (Neuro Probe; MD, USA) as described previously (51). Briefly, 25 μl KC (100 ng/ml in RPMI/1% FCS) was added to the bottom chamber, on top of which was placed a 5 μm pore size membrane filter followed by a silicone gasket and the top chamber. Neutrophil suspensions (1×105 in 50 μl RPMI/1 % FCS) were applied to the top chamber then incubated for various durations (10-90 mins) in a 37°C incubator in 5% CO2. The number of cells that migrated to the lower chamber was counted using a hemocytometer.

Leukocyte adhesion molecule and chemokine receptor expression

Bone marrow derived neutrophils were examined for expression of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors using flow cytometry. The following antibodies were used (from BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, unless stated otherwise): anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11), anti-Gr1 (RB6-8C5), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD11a (M17/4 – BioLegend), San Diego, CA), anti-CD11b (M1/70), and anti-CXCR2 (242216) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). FITC-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Silenus. Cells were labelled with appropriate antibody cocktails then analysed on a MoFlo flow cytometer (Dako-Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO). Data were compared to cells labelled in an identical fashion with an isotype control antibody.

Cell lysate preparation and Western blot analysis

Cells were cultured at various timepoints in RPMI/0.1% FCS at 37°C, 5% CO2 in the presence or absence of KC (100 ng/ml). PMA (30 ng/ml, 10 mins) was used as a positive control. Cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies directed against phosphorylated (P) and total (T) p38 and ERK1/2 (27). Briefly, equal amounts of cellular proteins were fractionated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels and transferred to Hybond-C extra nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked with blocking buffer then incubated sequentially with appropriate primary and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies. Membrane blot densitometry was performed using the Odyssey system (Li-Cor Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE), and data normalized to total protein content.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Mann-Whitney test for comparisons of group means of clinical and histological scores, or Student's t-test for comparisons of continuous variables. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. For each test, values of p < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Deficiency of MIF attenuates K/BxN serum transfer arthritis

We first sought to examine the effect of MIF in K/BxN serum transfer arthritis, a model of RA which is primarily mediated by neutrophil and macrophage accumulation, and is independent of T cell-mediated adaptive immunity. Preliminary experiments, continued to day 10 after first serum injection, demonstrated that disease severity in MIF-/- mice was markedly below that in MIF+/+ mice at all time points, and that disease severity tended to diminish beyond day 9 in both groups. We therefore elected to terminate the definitive experiments at day 8. In response to K/BxN serum transfer, WT mice exhibited severe ankle swelling and erythema, while in contrast these responses were not seen in MIF-/- mice (Fig. 1A, B). WT mice exhibited clinical disease as early as day 2, progressing to severe disease by day 8, as indicated by increased clinical index (Fig. 1C) and ankle thickness (Fig. 1D). In contrast, MIF-/- mice had significantly decreased clinical index and ankle thickness relative to that seen in WT mice (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1. Effect of MIF deficiency on K/BxN serum transfer arthritis.

WT and MIF-/-mice were injected with K/BxN sera (days 0 & 2) and arthritis severity assessed daily for 8 days. A, B: Representative photomicrographs of ankles of WT (A) and MIF-/- (B) mice at the completion of the experiment (day 8). Clinical index over the 8 day experimental time course (C), and change in ankle thickness (D) as assessed on day 8 in the three strains of mice. Data represent mean ± sem of n=4/group. *, p < 0.05 for WT mice versus MIF-/- mice. E-H: Histological assessment of K/BxN arthritis in safranin-O-stained sections of ankle joints. E, F: Representative joint sections (X200) of WT (E) and MIF-/- (F) mice demonstrating the reduction in histological manifestations of arthritis in MIF-/- mice. G: Scoring (0-3) of synovial sections for synovitis, joint space exudate, cartilage destruction and bone damage, and (H) total histological score (max = 12) for WT and MIF-/- mice. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 versus WT mice.

Histological examination of safranin-O-stained ankle joints in WT mice with K/BxN serum transfer arthritis showed increased synovial hypercellularity, and cartilage and bone damage, characteristic of severe arthritis (Fig. 1E). This resulted in high scores for synovitis, exudate, cartilage destruction and bone damage and consequently a high total histology score (Fig. 1G, H). In contrast, MIF-/- mice had significantly less histological disease (Fig. 1F-H). Relative to WT mice, MIF-/- mice had significantly lower scores for synovitis and joint space exudate, parameters reflecting the effects of leukocyte recruitment to the joint. Cartilage damage and bone damage were also significantly attenuated in the absence of MIF (Fig. 1E-G). Although a role for MIF has been established in other experimental models of arthritis, these are the first data demonstrating a similar role in K/BxN serum transfer arthritis.

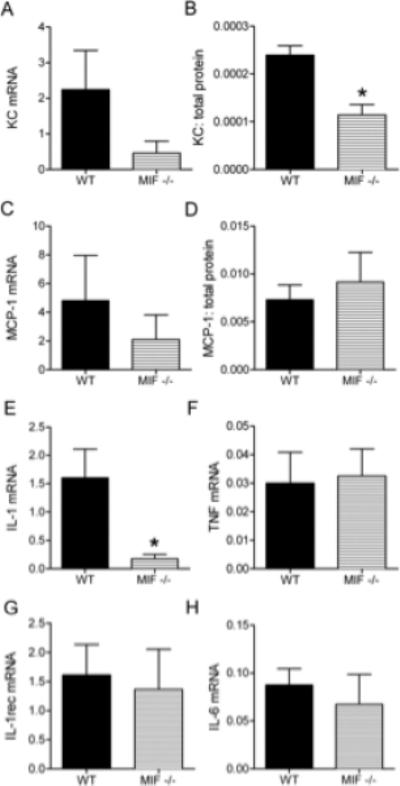

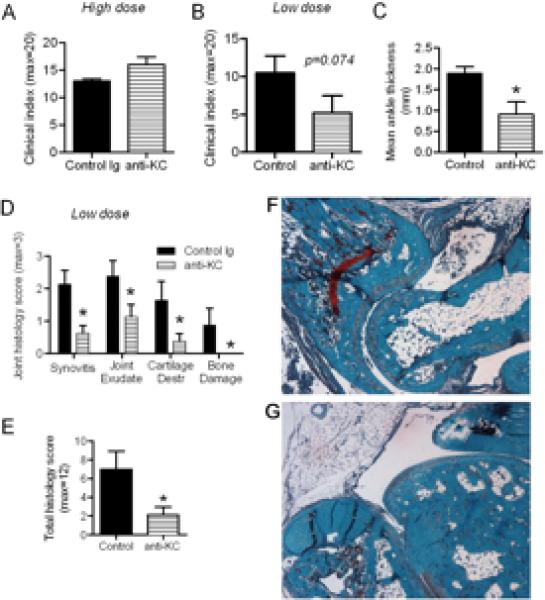

Further analysis of joint tissues from MIF-deficient mice cells revealed significant reductions in synovial expression of KC and the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1 (Fig. 2). Although IL-1 has been previously demonstrated to be essential for this model of arthritis, the role of KC had until recently not been reported. This prompted us to compare the effect on arthritis development of KC inhibition. In initial studies using high dose K/BxN sera, as used in MIF-/-mice, no difference in arthritis severity was observed between control-Ig-treated mice and mice treated with an anti-KC antibody (Fig. 3A). Induction of disease with a lower dose of serum resulted in a more variable disease onset, but clinical and histological disease were still comparable to the high dose protocol. Under these conditions, anti-KC-treated mice displayed less ankle swelling and erythema as reflected in a trend towards lower clinical index (p=0.07) and significantly reduced ankle thickness (Fig. 3B, C). These reductions were associated with decreased histological disease severity as demonstrated by significant reductions in all histological parameters (synovitis, exudate, cartilage and bone damage) (Fig. 3D-G). Finally, to provide further comparison of the effects of MIF with those of chemokines in this model, we also examined MCP-1-/- mice. In response to either high or low dose K/BxN serum administration, arthritis did not significantly differ between WT and MCP-1-/- animals (data not shown). Similarly, there was no difference in histological parameters between WT and MCP-1-/- mice in either model (data not shown). These findings confirm the recently reported involvement of ligands of CXCR2, such as KC, and lack of involvement of MCP-1 in the pathogenesis of K/BxN serum transfer arthritis (10). However, the disparity in the relative magnitude of the effects of MIF-deficiency and KC inhibition suggested that the actions of MIF on synovial neutrophil recruitment may extend beyond regulation of KC expression, to also influence the ability of neutrophils to respond to chemoattractants, and therefore enter the inflamed joint. We therefore investigated the role of MIF in neutrophil responses to KC.

Figure 2. Effect of MIF deficiency on synovial chemokine and cytokine expression in K/BxN serum transfer arthritis.

Synovial tissue was collected from WT and MIF-/- mice on day 8, and mRNA and protein levels of various molecules analysed by real-time PCR and ELISA, respectively. Shown are mRNA and protein levels of KC (A, B) & MCP-1 (C, D), and mRNA levels of IL-1 (E), TNF (F), IL-1R (G) and IL-6 (H). mRNA data are expressed relative to 18s expression. Chemokine protein levels are expressed relative to total protein. N=4 mice/group. * denotes p < 0.05 versus WT mice.

Figure 3. Effect of KC inhibition on arthritis severity in the low dose K/BxN serum transfer arthritis model.

A: Clinical index of arthritis severity in the high dose K/BxN serum transfer protocol in anti-KC and control Ig-treated mice (n=4/gp). B-G: Results of analysis of mice undergoing the low dose serum transfer protocol and treatment with either control Ig or anti-KC (n=4/gp). Clinical index (B) and mean ankle thickness (C) are shown. D: Histological scoring (0-3) of synovial sections for synovitis, joint space exudate, cartilage destruction and bone damage, and total histological score (E) in mice which underwent the low dose serum transfer protocol and anti-KC treatment. F, G: Representative joint sections (X200) of mice treated with control Ig (F) or anti-KC (G) demonstrating the histological manifestations of arthritis in the low dose serum transfer model (F), and their reduction in anti-KC-treated mice (G). N=4 mice/gp. * denotes p < 0.05 versus control Ig-treated mice.

Chemokine-induced leukocyte recruitment in vivo is impaired in MIF-/- mice

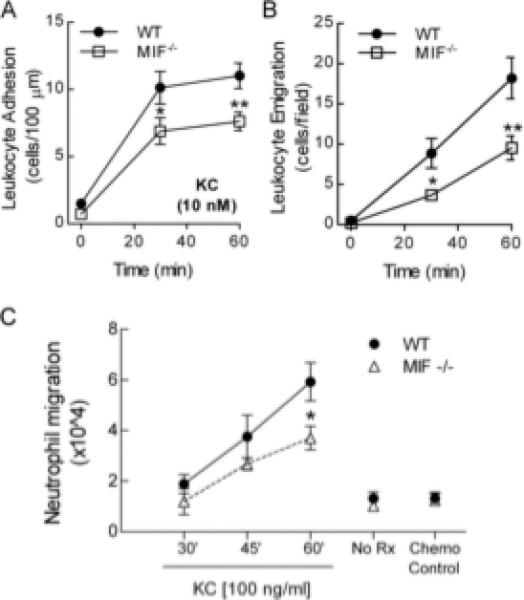

MIF has been reported to facilitate leukocyte-endothelial interactions during inflammatory responses to stimuli such as carrageenan, LPS or TNF, but the participation of MIF in responses to chemokines has not been investigated. We investigated the effect of MIF on leukocyte recruitment responses induced by KC. In WT mice, KC superfusion induced substantial leukocyte adhesion within 30 mins (Fig. 4A). Robust leukocyte emigration was also observed, reaching peak levels at 60 mins (Fig. 4B). In MIF-/- mice, KC-induced adhesion was significantly blunted (Fig. 4A), and the KC-induced emigration response was significantly reduced relative to that in WT mice (Fig. 4B). Together these data indicate that MIF acts in a previously unappreciated fashion to facilitate chemokine-induced recruitment of neutrophils in vivo.

Figure 4. Effect of MIF on leukocyte responses to chemokines in the intact microvasculature.

A & B: Leukocyte adhesion (A), and emigration (B) in cremasteric postcapillary venules of WT mice induced by superfusion with KC (10 nM), as determined by intravital microscopy (n=6/gp for each) after 0, 30 & 60 mins of KC superfusion. *, p < 0.05 vs WT; **, p < 0.01 vs WT. C. Comparison of in vitro migratory function of neutrophils from WT and MIF-/- mice. Neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow and migratory responses to KC (100 ng/ml) quantitated after 30, 45 and 60 min. Also shown are 60 min data for controls performed in the absence of KC (No Rx), and with addition of KC (100 ng/ml) to upper and lower wells (Chemokinesis control – ‘Chemo Control’). Data represent mean ± sem of at least six individual assays. *, p < 0.05 vs WT.

MIF-/- neutrophils have impaired migratory responses to KC

As MIF is expressed in endothelial cells and resident cells in sites of inflammation (52), we next sought to determine if the effects of MIF deficiency on leukocyte recruitment were due to effects on the intrinsic migratory potential of leukocytes. This was assessed by examination of in vitro migration responses of leukocytes isolated from WT and MIF-/- mice. Neutrophils from WT mice responded to KC in a time-dependent fashion, with peak levels being reached after 60 min (Fig. 4C). Minimal migration was seen when the chemokine was added to the upper well, indicating that the observed migration was genuine chemotaxis. KC-induced migration of neutrophils from MIF-/- mice was significantly reduced relative to that of WT neutrophils at the 60 min time point (Fig. 4C). Migration in response to the eicosanoid LTB4, also an important chemoattractant in K/BxN arthritis (10), was unaltered by MIF deficiency (data not shown), indicating that the effects of MIF are at least in part selective to chemokine-induced migration.

MIF-/- cells have normal expression of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors

Collectively, the above findings suggest that MIF expressed by neutrophils facilitates their migratory response to the chemokine KC. Reduced cytokine-induced responses in MIF-/- cells have previously been demonstrated to be associated with decreased cytokine receptor expression (43), and chemokine receptors, including the receptor for KC, CXCR2, are essential for the expression of K/BxN serum transfer arthritis (10). These observations raise the possibility that altered chemokine receptor expression may underlie the deficient migratory responses observed in leukocytes from MIF-/- mice. Therefore we examined leukocyte expression of chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules (Table 1). Neutrophils from WT and MIF-/- mice displayed comparable expression of CD11a, CD11b and CXCR2. These data indicate that alteration in expression of these key receptors is unlikely to underlie the observed reduction in migration in K/BxN arthritis and in response to KC seen in MIF-/-mice.

Table 1.

Expression of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors on neutrophils from WT and MIF-/- mice

| Strain | CD11a (MFI) | CD11b (MFI) | L-selectin (MFI) | CXCR2 (% positive) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type (n=3) | 118 ± 65 | 62 ± 8 | 24 ± 0.6 | 40 ± 10 |

| MIF-/- (n=3) | 67 ± 24 | 73 ± 8 | 25 ± 4 | 49 ± 2 |

| P value | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Data are derived from analysis of bone marrow-derived neutrophils and macrophages as described in the Materials ± Methods, and represent MFI of staining for CD11a, CD11b and L-selectin, and % positive for CXCR2, relative to isotype control. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

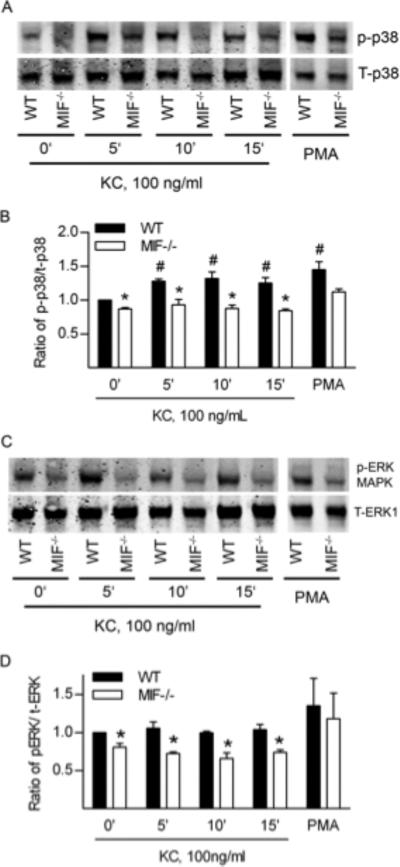

Reduced chemokine-induced MAP kinase phosphorylation in MIF-/- neutrophils

Impaired chemotactic responses to chemokines in MIF-/- neutrophils despite normal chemokine receptor expression suggested that MIF modulates chemokine-induced activation of intracellular signalling pathways. We therefore studied signalling pathways (ERK and p38 MAP kinases, and PI3K-Akt) that have been implicated in chemokine-induced leukocyte recruitment in other systems. Examination of KC-induced MAPK activation in WT neutrophils revealed time-dependent phosphorylation of p38 but not ERK MAPK (Fig. 5AD). Basal phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was reduced in MIF-/- neutrophils, and KC failed to induce phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in MIF-/- neutrophils (Fig. 5A, B). Although KC did not induce phosphorylation of ERK MAPK in WT neutrophils, phospho-ERK MAPK was lower in MIF-/- cells, both basally and after KC stimulation (Fig. 5C, D). In contrast, MAPK phosphorylation induced by PMA did not differ between WT and MIF-/- neutrophils, indicating that the perturbation in signaling seen in the absence of MIF did not extend to all stimuli. Akt phosphorylation was not detected in response to KC treatment (data not shown). These results indicate a requirement for MIF for basal activation of p38 and ERK MAPK in neutrophils, and for activation of neutrophil p38 MAPK by KC.

Figure 5. Comparison of MAP kinase activation in neutrophils from WT and MIF-/- mice.

A-D: Western blot analysis of ERK and p38 phosphorylation in neutrophils from WT, and MIF-/- mice. Neutrophils were exposed to KC (100 ng/mL) for 0-15 min. As a positive control, additional cells were exposed to PMA (30 ng/ml, 10 min; samples shown in separate gel due to space limitations). Subsequently, cell lysates were examined for total p38 MAPK (T-p38) and phosphorylated p38 MAPK (p-p38) (A, B) or total ERK (T-ERK1) and phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) (C, D) via Western blot. A, C: Representative blots from n=3 independent experiments. B, D: Densitometric analysis showing ratio of p-p38 to total p38 (B) or p-ERK to total ERK (D). Data are shown as mean ± sem. #, p < 0.05 vs untreated WT cells. *, p < 0.05 vs WT at time point shown.

DISCUSSION

MIF has been shown to influence multiple pathways important to the pathogenesis of RA. These include innate and adaptive immune responses (30, 31), synovial fibroblast proliferation and cytokine and chemokine expression (26, 28), immune cell and synovial fibroblast apoptosis (21, 53), and matrix metalloproteinase expression (54). As noted earlier, the contribution of neutrophils to the pathogenesis of RA is not clear, but these cells constitute the majority of cells in RA synovial fluid, and interventions targeting neutrophils and their recruitment are effective in numerous animal models of RA. A number of recent observations suggested the hypothesis tested here, that MIF contributes to neutrophil chemotactic responses. MIF was reported to support neutrophil recruitment in reverse passive arthus, a model of complement dependent inflammation (41). Intratracheal MIF induces neutrophil recruitment and increased expression of KC (36), while LPS-induced airway neutrophil recruitment is also dependent on MIF (40). Anti-MIF antibody treatment in a model of asthma resulted in reduced recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils (38), and MIF-overexpressing transgenic mice exhibit increased neutrophil recruitment in a model of inflammatory bowel disease (37). Our own previous reports, while demonstrating that exogenous MIF induces significant monocyte recruitment, also demonstrate significant MIF-induced neutrophil recruitment (32), and we have also reported that endogenous MIF supported neutrophil recruitment to the joint in response to carrageenan injection (35). Given the impact of endogenous MIF on multiple aspects of immunity, to investigate the effects of MIF on neutrophil chemokine responses it was necessary to use models in which MIF or chemokine effects on adaptive immunity were immaterial, and in which direct responses to chemokines can be tested. K/BxN serum transfer arthritis, which is independent of adaptive immune responses but dependent on recruitment of neutrophils, was chosen for these studies so as to isolate effects of MIF on leukocyte recruitment from any effects on adaptive immune responses. In the current study, MIF-/- mice exhibited markedly decreased clinical arthritis severity, associated with reduced synovial leukocyte accumulation, indicating a critical role for MIF in inflammation and leukocyte migration in this model. It was noteworthy that the absence of MIF was markedly more protective than inhibition or absence respectively of either of the chemokines KC or MCP-1. The present findings show that MIF also increases the ability of the leukocytes to respond to chemotactic cues known to be expressed in inflamed joints. This ability to impact on multiple elements of the inflammatory response may underlie the ability of MIF to contribute to a wide array of inflammatory models.

Recently, Jacobs et al, reported that CXCR2 was the dominant chemokine receptor in the K/BxN arthritis model, with other chemokine receptors including CCR2 tested being relatively non-contributory (10). The current findings lend support to those observations, in that targeting KC, a ligand for CXCR2, but not MCP1, a ligand for CCR2, was effective in inhibiting the expression of K/BxN arthritis. In the current study, MIF deficiency reduced KC expression in K/BxN arthritis, but the current findings further indicate a more powerful effect of MIF than that attributable to alterations in chemokine expression alone. The inhibition, in MIF-deficient mice, of joint IL-1 expression suggests one possible action of MIF in this model. IL-1 is known to be crucial for this model of arthritis (55), but we consider this unlikely to fully explain the effects of MIF deficiency, as we also demonstrate that MIF deficiency is associated with reductions in in vivo neutrophil migratory and responses to KC. Reductions in leukocyte migratory function were also observed in vitro, in neutrophils isolated from MIF-/- mice, indicating that the effect of MIF deficiency on chemokine-induced responses was intrinsic to the neutrophils. These findings are the first evidence of an effect of MIF on chemoattractant-induced leukocyte migration, and identify this as a previously unrecognized mechanism whereby MIF promotes leukocyte recruitment.

During chemotaxis, major signaling pathways activated by chemoattractants include p38 MAP kinase and PI(3)K/Akt, with emerging evidence of a role for ERK MAP kinase. We and others have shown MIF-dependent activation of ERK, p38, JNK and Akt (26, 27, 43, 56). MIF-deficient fibroblasts exhibit reduced MAP kinase activation in response to IL-1 and TNF, (43), and we have also reported impaired ERK MAP kinase activation in the setting of antigen-specific activation of T lymphocytes (44). In the current studies, we demonstrate that MIF is required for chemokine activation of MAP kinases in neutrophils, either basally in the case of ERK MAP kinase or in response to KC in the case of p38 MAP kinase. These data indicate that constitutively-expressed MIF promotes neutrophil recruitment via facilitation of intracellular signaling crucial to chemoattractant responses. These findings provide a mechanism explaining the altered in vitro and in vivo migration observed in leukocytes lacking MIF. Moreover, these data indicate that MIF has a previously unappreciated role in promoting inflammation via facilitation of neutrophil intracellular signaling responses to chemokines.

The mechanism through which MIF modulates chemokine-induced MAP kinase activation in myeloid cells is not well understood. Swant et al reported activation of RhoA GTPase, and Rho-dependent stress fiber formation, during MIF-mediated ERK MAP kinase activation in a murine fibroblast cell line (57). An alternate mechanism whereby MIF may influence p38 MAP kinase activation may stem from its effect on the dual-specificity phosphatase (DUSP) DUSP1, also known as MAP kinase phosphatase (MKP) MKP1. MIF has been reported to inhibit the expression of MKP1 in macrophages, as demonstrated by increased expression of MKP1 in MIF-deficient cells, leading to impaired p38 MAPK activation (58, 59). MIF inhibition of MKP-1 could underpin the current observations of reduced MAPK phosphorylation in MIF-/- cells, but the effect of MIF on MKP1 expression in neutrophils is not currently known.

In summary, we demonstrate here that deficiency of endogenous MIF significantly attenuates the expression of K/BxN serum transfer arthritis, a model which is at least in part dependent on KC/CXCL1. In addition, MIF deficiency is associated with impairment of in vitro and in vivo KC-induced neutrophil migration and MAP kinase activation. These findings add amplification of neutrophil chemokine responses to the range of biological processes impacted on by endogenous MIF. These previously unrecognized actions of MIF add to the evidence implicating it as a key facilitator of inflammatory responses in vivo. The multiple aspects of the immune-inflammatory response on which MIF impacts suggest that therapeutic targeting of MIF could be a powerful means of limiting the harmful effects of chronic inflammatory disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a Program Grant from the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (#334067), and RO1 grants from the NIH (#AR51807-01, #AR50498). MJH is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow. GFR was supported by grant Fi 712/2-1 from the German Research Council (DFG).

The authors wish to thank Ms April Dacumos and Ms Ran Gu for technical assistance, and Prof Shaun McColl (University of Adelaide) for provision of anti-CXCR2.

Footnotes

Disclosures. EM is a consultant to and shareholder in Cortical Pty Ltd and an inventor on patents of MIF inhibitors. RB is a consultant to Carolus Therapeutics and an inventor on patents for MIF therapies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Shah MR, Hosaka S, Halloran MM, Haines GK, et al. Growth-related gene product alpha. A chemotactic cytokine for neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 1995;155(7):3660–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos LL, Morand EF, Hutchinson P, Boyce NW, Holdsworth SR. Anti-neutrophil monoclonal antibody therapy inhibits the development of adjuvant arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107(2):248–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.263-ce1154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eyles JL, Hickey MJ, Norman MU, Croker BA, Roberts AW, Drake SF, et al. A key role for G-CSF-induced neutrophil production and trafficking during inflammatory arthritis. Blood. 2008;112(13):5193–201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CR, Blaho VA, Loiacono CM. Susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis correlates with KC and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production in joints and requires neutrophil recruitment via CXCR2. J. Immunol. 2003;171(2):893–901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verri WA, Jr., Souto FO, Vieira SM, Almeida SC, Fukada SY, Xu D, et al. IL-33 induces neutrophil migration in rheumatoid arthritis and is a target of anti-TNF therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 May 14; doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122655. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grespan R, Fukada SY, Lemos HP, Vieira SM, Napimoga MH, Teixeira MM, et al. CXCR2-specific chemokines mediate leukotriene B4-dependent recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed joints in mice with antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(7):2030–40. doi: 10.1002/art.23597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coelho FM, Pinho V, Amaral FA, Sachs D, Costa VV, Rodrigues DH, et al. The chemokine receptors CXCR1/CXCR2 modulate antigen-induced arthritis by regulating adhesion of neutrophils to the synovial microvasculature. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(8):2329–37. doi: 10.1002/art.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes DA, Tse J, Kaufhold M, Owen M, Hesselgesser J, Strieter R, et al. Polyclonal antibody directed against human RANTES ameliorates disease in the Lewis rat adjuvant-induced arthritis model. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(12):2910–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wipke BT, Allen PM. Essential role of neutrophils in the initiation and progression of a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1601–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JP, Ortiz-Lopez A, Campbell JJ, Gerard CJ, Mathis D, Benoist C. Deficiency of CXCR2, but not other chemokine receptors, attenuates a murine model of autoantibody-mediated arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):1921–1932. doi: 10.1002/art.27470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillipson M, Heit B, Colarusso P, Liu L, Ballantyne CM, Kubes P. Intraluminal crawling of neutrophils to emigration sites: a molecularly distinct process from adhesion in the recruitment cascade. J Exp Med. 2006;203(12):2569–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heit B, Robbins SM, Downey CM, Guan Z, Colarusso P, Miller BJ, et al. PTEN functions to ‘prioritize’ chemotactic cues and prevent ‘distraction’ in migrating neutrophils. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(7):743–52. doi: 10.1038/ni.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinashi T. Intracellular signalling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5(7):546–59. doi: 10.1038/nri1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarbock A, Lowell CA, Ley K. Spleen tyrosine kinase Syk is necessary for E-selectin-induced alpha(L)beta(2) integrin-mediated rolling on intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Immunity. 2007;26(6):773–83. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang HB, Wang JT, Zhang L, Geng ZH, Xu WL, Xu T, et al. P-selectin primes leukocyte integrin activation during inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8(8):882–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heit B, Tavener S, Raharjo E, Kubes P. An intracellular signaling hierarchy determines direction of migration in opposing chemotactic gradients. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(1):91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashida N, Arai H, Yamasaki M, Kita T. Distinct signaling pathways for MCP-1-dependent integrin activation and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):16555–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuhler GM, Knol GJ, Drayer AL, Vellenga E. Impaired interleukin-8- and GROalpha-induced phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase result in decreased migration of neutrophils from patients with myelodysplasia. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77(2):257–66. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cara DC, Kaur J, Forster M, McCafferty DM, Kubes P. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in chemokine-induced emigration and chemotaxis in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6552–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morand EF, Leech M, Bernhagen J. MIF: a new cytokine link between rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(5):399–410. doi: 10.1038/nrd2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leech M, Lacey D, Xue JR, Santos L, Hutchinson P, Wolvetang E, et al. Regulation of p53 by macrophage migration inhibitory factor in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(7):1881–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leech M, Metz C, Bucala R, Morand EF. Regulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor by endogenous glucocorticoids in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(4):827–33. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<827::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leech M, Metz C, Santos L, Peng T, Holdsworth SR, Bucala R, et al. Involvement of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the evolution of rat adjuvant arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(5):910–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<910::AID-ART19>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos L, Hall P, Metz C, Bucala R, Morand EF. Role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in murine antigen-induced arthritis: interaction with glucocorticoids. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123(2):309–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leech M, Metz C, Hall P, Hutchinson P, Gianis K, Smith M, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in rheumatoid arthritis: evidence of proinflammatory function and regulation by glucocorticoids. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(8):1601–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1601::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacey D, Sampey A, Mitchell R, Bucala R, Santos L, Leech M, et al. Control of fibroblast-like synoviocyte proliferation by macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):103–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos LL, Lacey D, Yang Y, Leech M, Morand EF. Activation of synovial cell p38 MAP kinase by macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(6):1038–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampey AV, Hall PH, Mitchell RA, Metz CN, Morand EF. Regulation of synoviocyte phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase 2 by macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1273–80. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1273::AID-ART219>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radstake TR, Sweep FC, Welsing P, Franke B, Vermeulen SH, Geurts-Moespot A, et al. Correlation of rheumatoid arthritis severity with the genetic functional variants and circulating levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3020–9. doi: 10.1002/art.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernhagen J, Calandra T, Mitchell RA, Martin SB, Tracey KJ, Voelter W, et al. MIF is a pituitary-derived cytokine that potentiates lethal endotoxaemia. Nature. 1993;365(6448):756–9. doi: 10.1038/365756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bacher M, Metz CN, Calandra T, Mayer K, Chesney J, Lohoff M, et al. An essential regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(15):7849–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregory JL, Morand EF, McKeown SJ, Ralph JA, Hall P, Yang YH, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces macrophage recruitment via CC chemokine ligand 2. J Immunol. 2006;177(11):8072–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernhagen J, Krohn R, Lue H, Gregory JL, Zernecke A, Koenen RR, et al. MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):587–96. doi: 10.1038/nm1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregory JL, Hall P, Leech M, Morand EF, Hickey MJ. Independent roles of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor and endogenous, but not exogenous glucocorticoids in regulating leukocyte trafficking. Microcirculation. 2009;16(8):735–748. doi: 10.3109/10739680903210421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gregory JL, Leech MT, David JR, Yang YH, Dacumos A, Hickey MJ. Reduced leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in the inflamed microcirculation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):3023–34. doi: 10.1002/art.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takahashi K, Koga K, Linge HM, Zhang Y, Lin X, Metz CN, et al. Macrophage CD74 contributes to MIF-induced pulmonary inflammation. Respir Res. 2009;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohkawara T, Miyashita K, Nishihira J, Mitsuyama K, Takeda H, Kato M, et al. Transgenic over-expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor renders mice markedly more susceptible to experimental colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140(2):241–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02771.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi M, Nasuhara Y, Kamachi A, Tanino Y, Betsuyaku T, Yamaguchi E, et al. Role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in rats. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):726–34. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00107004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amaral FA, Fagundes CT, Guabiraba R, Vieira AT, Souza AL, Russo RC, et al. The role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the cascade of events leading to reperfusion-induced inflammatory injury and lethality. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(6):1887–93. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makita H, Nishimura M, Miyamoto K, Nakano T, Tanino Y, Hirokawa J, et al. Effect of anti-macrophage migration inhibitory factor antibody on lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary neutrophil accumulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(2):573–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9707086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paiva CN, Arras RH, Magalhaes ES, Alves LS, Lessa LP, Silva MH, et al. Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) released by macrophages upon recognition of immune complexes is critical to inflammation in Arthus reaction. J Leukoc Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aeberli D, Yamana J, Yang Y, Morand E. Modulation of glucocorticoid sensitivity by MIF via MAP kinase phosphatase-1 is dependent on p53. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):S94–S94. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toh ML, Aeberli D, Lacey D, Yang Y, Santos LL, Clarkson M, et al. Regulation of IL-1 and TNF receptor expression and function by endogenous macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Immunol. 2006;177(7):4818–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos LL, Dacumos A, Yamana J, Sharma L, Morand EF. Reduced arthritis in MIF deficient mice is associated with reduced T cell activation: down-regulation of ERK MAP kinase phosphorylation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152(2):372–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fingerle-Rowson G, Petrenko O, Metz CN, Forsthuber TG, Mitchell R, Huss R, et al. The p53-dependent effects of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(16):9354–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, Fiorillo J, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, et al. Abnormalities in monocyte recruitment and cytokine expression in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187(4):601–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pettit AR, Ji H, von Stechow D, Muller R, Goldring SR, Choi Y, et al. TRANCE/RANKL knockout mice are protected from bone erosion in a serum transfer model of arthritis. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159(5):1689–99. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corr M, Crain B. The role of FcgammaR signaling in the K/B x N serum transfer model of arthritis. J. Immunol. 2002;169(11):6604–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang YH, Morand EF, Getting SJ, Paul-Clark M, Liu DL, Yona S, et al. Modulation of inflammation and response to dexamethasone by Annexin 1 in antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(3):976–84. doi: 10.1002/art.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hickey MJ, Forster M, Mitchell D, Kaur J, De Caigny C, Kubes P. L-selectin facilitates emigration and extravascular locomotion of leukocytes during acute inflammatory responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:7164–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Falk W, Goodwin RH, Jr., Leonard EJ. A 48-well micro chemotaxis assembly for rapid and accurate measurement of leukocyte migration. J. Immunol. Methods. 1980;33(3):239–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishihira J, Koyama Y, Mizue Y. Identification of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in human vascular endothelial cells and its induction by lipopolysaccharide. Cytokine. 1998;10(3):199–205. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell RA, Liao H, Chesney J, Fingerle-Rowson G, Baugh J, David J, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) sustains macrophage proinflammatory function by inhibiting p53: regulatory role in the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(1):345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012511599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Onodera S, Kaneda K, Mizue Y, Koyama Y, Fujinaga M, Nishihira J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor up-regulates expression of matrix metalloproteinases in synovial fibroblasts of rheumatoid arthritis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(1):444–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji H, Pettit A, Ohmura K, Ortiz-Lopez A, Duchatelle V, Degott C, et al. Critical roles for interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in antibody-induced arthritis. J Exp Med. 2002;196(1):77–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amin MA, Haas CS, Zhu K, Mansfield PJ, Kim MJ, Lackowski NP, et al. Migration inhibitory factor up-regulates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 via Src, PI3 kinase, and NFkappaB. Blood. 2006;107(6):2252–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swant JD, Rendon BE, Symons M, Mitchell RA. Rho GTPase-dependent signaling is required for macrophage migration inhibitory factor-mediated expression of cyclin D1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(24):23066–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500636200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aeberli D, Yang Y, Mansell A, Santos L, Leech M, Morand EF. Endogenous macrophage migration inhibitory factor modulates glucocorticoid sensitivity in macrophages via effects on MAP kinase phosphatase-1 and p38 MAP kinase. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(3):974–81. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roger T, Chanson AL, Knaup-Reymond M, Calandra T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes innate immune responses by suppressing glucocorticoid-induced expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(12):3405–13. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]