Abstract

During cell proliferation, the abundance of the glycolysis-promoting enzyme, 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase, isoform 3 (PFKFB3), is controlled by the ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Cdh1 via a KEN box. We now demonstrate in synchronized HeLa cells that PFKFB3, which appears in mid-to-late G1, is essential for cell division because its silencing prevents progression into S phase. In cells arrested by glucose deprivation, progression into S phase after replacement of glucose occurs only when PFKFB3 is present or is substituted by the downstream glycolytic enzyme 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase. PFKFB3 ceases to be detectable during late G1/S despite the absence of Cdh1; this disappearance is prevented by proteasomal inhibition. PFKFB3 contains a DSG box and is therefore a potential substrate for SCF-β-TrCP, a ubiquitin ligase active during S phase. In synchronized HeLa cells transfected with PFKFB3 mutated in the KEN box, the DSG box, or both, we established the breakdown routes of the enzyme at different stages of the cell cycle and the point at which glycolysis is enhanced. Thus, the presence of PFKFB3 is tightly controlled to ensure the up-regulation of glycolysis at a specific point in G1. We suggest that this up-regulation of glycolysis and its associated events represent the nutrient-sensitive restriction point in mammalian cells.

Cell division is a finely coordinated process in which the timely functioning and degradation of cell cycle progression proteins play a fundamental role. Two ubiquitin ligase complexes—SCF (SKP1/CUL-1/F-box protein) and APC/C (anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome)—control the sequential degradation of these proteins (1). SCF is active mainly in G1, S, and early M phases, whereas APC/C regulates mitosis and G1. These complexes recognize specific amino acid motifs (e.g., the KEN box, D box, or DSG box) in their substrates through the action of activator proteins such as SKP2, β-TrCP and Fbw7 in the case of SCF or Cdc20 and Cdh1 in the case of APC/C (2–4).

APC/C-Cdh1 maintains normal cells in G1, thus preventing their uncoordinated entry into a new cell cycle (5). This is achieved through the degradation of a number of proteins involved in progression into S phase (6). Initiation of the cell cycle leads to the eventual decrease in APC/C-Cdh1 activity and the consequent appearance of S/M cyclins responsible for entry into S phase—the biosynthetic step of the cycle. The point in G1 at which the availability of key exogenous nutrients is required, and after which the cells become independent of growth factors, was described many years ago as the restriction point (7, 8). However, the mechanisms underlying the provision of the substrates necessary for a cell’s commitment to proliferate have remained elusive.

We have recently found that PFKFB3 is regulated during cell proliferation by APC/C-Cdh1 and that silencing this enzyme prevents cells from entering S phase (9, 10). These findings suggest that there is close coordination between cell cycle progression and provision of the raw materials required for its completion. We have now monitored the expression of PFKFB3 during the cell cycle in HeLa cells synchronized by double thymidine block (DTB) and nocodazole. We have located its appearance during the cell cycle, identified its degradation routes, and established its significance for the regulation of glycolysis and cell cycle progression.

Results

Appearance of the Glycolysis-Promoting Enzyme PFKFB3 During the Cell Cycle.

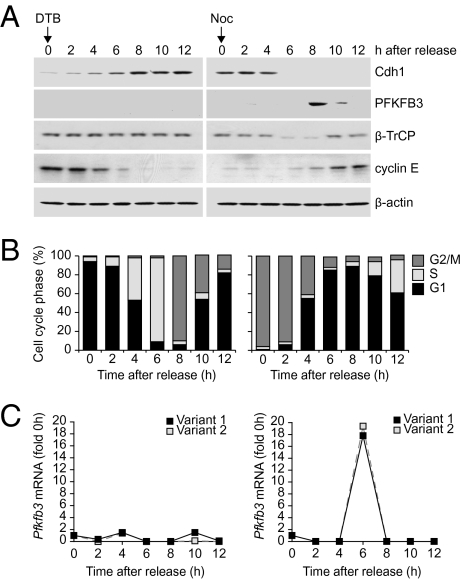

HeLa cells synchronized with DTB and nocodazole were released from mitotic arrest. Immunoblotting of cell extracts at 2-h intervals after release established that PFKFB3 protein levels were initially below the detection limit, then rose sharply for a brief period (at 8–10 h) before decreasing to background levels (Fig. 1A, Right). The appearance of PFKFB3 followed the disappearance (at 6 h) of the APC activator protein Cdh1 (Fig. 1A). Cell cycle analysis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1B) and immunoblotting for the G1/S phase marker cyclin E (Fig. 1A), established that levels peak in mid-to-late G1. After the short-lived peak, PFKFB3 disappeared, following an increase in the amount of β-TrCP detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 1A). PFKFB3 remained below the detection limit for the rest of the cell cycle, as demonstrated in cells released from DTB block at G1/S (Fig. 1A, Left). Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in RNA extracts from synchronously proliferating cells demonstrated that Pfkfb3 (variants 1 and 2) mRNA levels increased sharply ∼2 h before the rise in PFKFB3 protein levels (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Protein levels of the glycolysis-promoting enzyme PFKFB3 rise temporarily in mid- to late-G1 phase. (A) HeLa cells were released from double thymidine block (DTB) (Left) or DTB plus nocodazole (Right). Whole cell extracts from synchronized cells were subjected to immunoblotting at the indicated times after release. (B) The cell cycle profile of the cells at different times after release as determined by FACS analysis of DNA content. (C) Changes in Pfkfb3 (variants 1 and 2) mRNA levels at different times after release as determined by qRT-PCR. (A and C) Representative of three independent experiments. (B) Mean of three independent experiments.

Regulation of the Stability of PFKFB3 During the Cell Cycle.

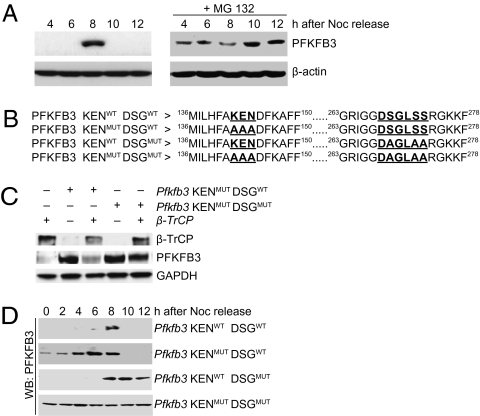

The role of proteasomal degradation in the cell cycle-dependent changes in the levels of PFKFB3 protein was next investigated. In cells synchronized by release from nocodazole arrest, PFKFB3 down-regulation before and after the brief peak of expression in mid-to-late G1 was shown to be prevented by the proteasome inhibitor MG 132 (Fig. 2A). This indicates that the absence of PFKFB3, both before and after the G1 peak, is due to proteasomal degradation and that the short-lasting expression of the gene for PFKFB3 is not the only explanation for the brief appearance of the protein. This led us to investigate why the protein ceases to be detectable despite the fact that APC/C-Cdh1 is not active after transition from G1 to S phase. Bioinformatic analysis showed that PFKFB3 contains a consensus motif for β-TrCP recognition (the DSGXXS motif). Using site-directed mutagenesis, three different mutated forms of PFKFB3 were produced: in one (PFKFB3 KENMUT DSGWT) the KEN box was changed to AAA, in another (PFKFB3 KENWT DSGMUT) the DSGXXS box was changed to DAGLAA, and finally a form containing both mutations (PFKFB3 KENMUT DSGMUT) was generated (Fig. 2B). The KEN box-mutated and the double-mutated forms were overexpressed in synchronized cells in the presence or absence of overexpressed β-TrCP. At 8 h after release from nocodazole, virtually no PFKFB3 was detectable in cells in which β-TrCP alone was overexpressed (Fig. 2C). Overexpression of β-TrCP in cells expressing the KEN box mutant reduced the amount of PFKFB3 detected but had no effect on protein levels in cells overexpressing the double-mutant (Fig. 2C) or the DSG-mutant form (Fig. S1). In a further set of experiments, the WT form (PFKFB3 KENWT DSGWT) and all of the mutated forms were overexpressed in cells synchronized first by DTB and then with nocodazole. Immunoblotting revealed that, whereas PFKFB3 was present in the WT background only at 6–8 h after release from nocodazole, it was detectable up to and including 8 h for the PFKFB3 KENMUT DSGWT form and from 8 h onward for the PFKFB3 KENWT DSGMUT form. The form containing mutations in both the KEN and DSG box was present at all times (up to 12 h) following release from nocodazole (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2). Thus, the DSG-mutated form was susceptible to destruction by Cdh1 from 0 to 6 h (Fig. 1A), as was the WT but not the KEN box-mutated or double-mutated form. In contrast, neither the DSG-mutated nor the double-mutated form (unlike the WT and PFKFB3MUT form) were susceptible to destruction after 8 h, at which time the cells were entering S phase and the level of β-TrCP was increasing (Fig. 1A). This indicates that PFKFB3 is subjected to proteasomal degradation by APC/C-Cdh1 (via the KEN box) when the cells are in early G1 and also by SCF (via β-TrCP and the DSG box) after the brief mid- to late-G1 peak.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of the stability of PFKFB3 during the cell cycle. (A) PFKFB3 is detectable by immunoblotting at 8 h in cells released from DTB and nocodazole (Left). Treatment with the proteasomal inhibitor MG 132 (2 h after release) resulted in detectable amounts of the protein at other time points. (B) Illustration of the WT PFKFB3 and various mutations carried out in the KEN box, the DSG box, and in both recognition sites. (C) Effect of overexpressed β-TrCP on PFKFB3 in synchronized (DTB plus nocodazole) cells. Immunoblotting was carried out 8 h after release in cells expressing only β-TrCP or in which the KEN box-mutated or the double-mutated forms of PFKFB3 were overexpressed in the presence or absence of overexpressed β-TrCP. (D) Time course of the appearance of PFKFB3 in synchronized cells overexpressing the WT form (PFKFB3 KENWT DSGWT) or the mutated forms shown in Fig. 2B (representative of three independent experiments).

Lactate Generation in the Presence of PFKFB3.

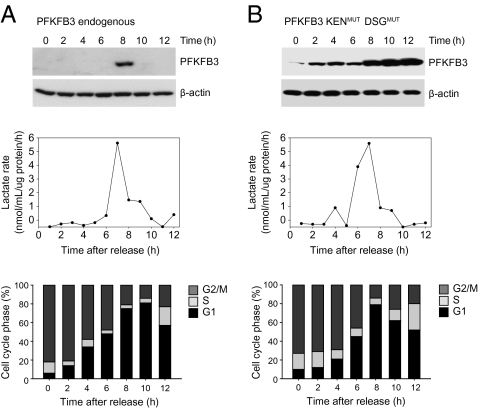

In cells expressing only endogenous PFKFB3 (Fig. 3A), the generation of lactate was enhanced for a short period at 7–9 h post-nocodazole. This coincided with the appearance of PFKFB3, as detected by immunoblotting, and preceded progression from G1 to S phase (Fig. 3A). In the double-mutant form, PFKFB3 was not only constantly present but it appeared to accumulate with time (Fig. 3B, Upper), possibly due to lack of metabolism as a result of its mutation. Despite this finding, lactate generation was enhanced for only a short period, at a similar time to that in cells expressing endogenous PFKFB3 and at a similar stage in the cell cycle (Fig. 3B). The metabolic competence of PFKFB3 KENMUT DSGMUT was demonstrated by the fact that this mutant restored lactate generation in asynchronous cells in which Cdh1 was overexpressed (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

PFKFB3 can only promote glycolysis at a certain stage of cell proliferation. (A) The appearance of PFKFB3 was compared with the production of lactate and the cell cycle stage in nontransfected cells synchronized by DTB plus nocodazole. Lactate was measured as the difference from the previous hour in the amount detected. (B) The same procedure was carried out in cells transfected with PFKFB3 KENMUT DSGMUT. Despite the constant presence of PFKFB3 in the double-mutant form during the cell cycle, the pattern of lactate generation was similar to that in cells that had not been transfected (representative of three to four independent experiments).

Effect of Silencing PFKFB3 in Synchronously Proliferating Cells.

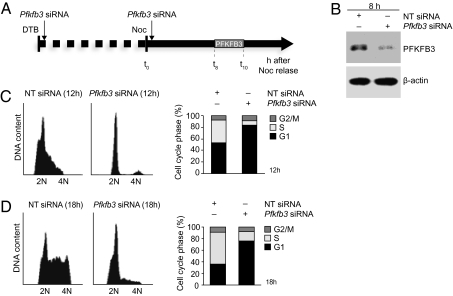

To investigate whether the rise in PFKFB3 levels is essential for passage through the restriction point and entry into S phase, G1 progression was monitored in synchronized cells in which PFKFB3 was silenced. Cells were released from DTB at G1/S, transfected with a Pfkfb3-siRNA SMART pool (or nontargeting siRNA), synchronized in mitosis by nocodazole treatment, released from nocodazole, and immediately retransfected with Pfkfb3 siRNA (or nontargeting siRNA) before being allowed to proceed with the cell cycle (Fig. 4A). PFKFB3 was efficiently silenced at the mRNA level in cells transfected with Pfkfb3 siRNA (70–80% knockdown; Fig. S4) so that at 8 h after release from nocodazole the amount of PFKFB3 protein was greatly reduced in these cells compared with that in cells transfected with nontargeting control siRNA (Fig. 4B). At 12 h after release, a significant number of control-transfected cells (40% of the cell population) were in S phase and a further 3% had progressed to G2/M (Fig. 4C). In contrast, in the PFKFB3-silenced group at 12 h there was an accumulation of cells with G1 DNA content (86% of the cell population) and very few cells (3%) in S phase. This cell population remained predominantly in G1 after 18 h, unlike the control-transfected cells, which were mostly in S phase (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Silencing PFKFB3 in synchronously proliferating cells blocks G1-to-S progression. (A) Schematic diagram showing experimental design for PFKFB3 silencing in cells synchronized by DTB plus nocodazole. (B) At 8 h after release from nocodazole arrest, PFKFB3 protein was present in cells transfected with nontargeting (NT) control siRNA but was greatly reduced in PFKFB3-silenced cells. (C) Flow cytometry profiles of DNA content (Left) and derived cell cycle phase distribution (Right) of synchronized cells transfected with NT siRNA or with Pfkfb3 siRNA 12 h after release from nocodazole and (D) 18 h after release from nocodazole. (B; and C and D, Left) Representative of three independent experiments. (C and D, Right) Mean of three independent experiments.

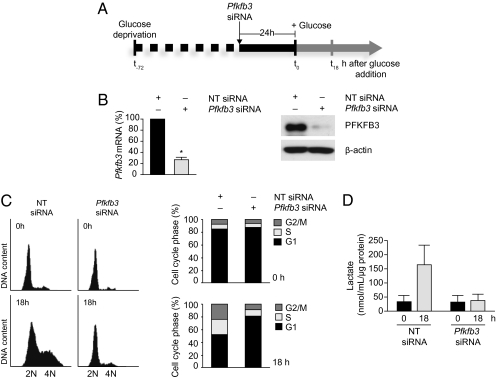

Effect of PFKFB3 on S Phase Entry in Glucose-Deprived Cells.

To investigate whether silencing PFKFB3 and glucose deprivation have a similar effect on cell proliferation, PFKFB3 was silenced in glucose-deprived cells and the cell cycle profile was monitored by FACS after restoration of glucose. Cells were incubated in glucose-free medium for 48 h and were then transfected with Pfkfb3 siRNA SMART pool (or nontargeting siRNA) and cultured in glucose-free medium for an additional 24 h. Cell viability (determined by the trypan blue exclusion test) at this time was 80% in the control transfected group and 72% in the PFKFB3-silenced group. Glucose was restored to the medium and cells incubated for a further 18 h (Fig. 5A), at which time PFKFB3 was efficiently silenced in cells transfected with Pfkfb3 siRNA, and PFKFB3 protein levels were significantly reduced (Fig. 5B). Flow cytometry showed that after incubation in glucose-free medium for 72 h (i.e., 0 h; Fig. 5A), the proportion of cells in S phase was <10% and that in G1 phase was 80–90% (Fig. 5C). By 18 h after replacement of glucose, the proportion of cells in S phase had doubled in control-transfected cells (Fig. 5C). This was associated with an increase in lactate production (Fig. 5D). Silencing PFKFB3 prevented the increase in the proportion of cells in S phase (Fig. 5C) as well as the increase in lactate production (Fig. 5D) observed 18 h after the addition of glucose.

Fig. 5.

PFKFB3 links glycolytic activity with S phase entry. (A) Schematic diagram showing design of experiment in which cells were deprived of glucose for 48 h, treated with Pfkfb3 siRNA (or nontargeting control siRNA), incubated in the absence of glucose for a further 24 h, and then incubated for 18 h in the presence of glucose. (B) qRT-PCR and immunoblots of cell lysates prepared 18 h after replacement of glucose showing that PFKFB3 mRNA and protein levels were significantly reduced in cells transfected with Pfkfb3 siRNA. (C) Flow cytometry profiles of DNA content (Left) and derived cell cycle phase distribution (Right) of control-transfected and PFKFB3-silenced cells incubated in glucose-free medium for 72 h (i.e., at 0 h) (Upper) and 18 h (Lower) after readdition of glucose. (D) Increase in lactate production in control-transfected but not PFKFB3-silenced cells 18 h after readdition of glucose. (B, Left, and D), mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (B, Right, and C, Left), representative of three independent experiments. (C, Right) Mean of three independent experiments.

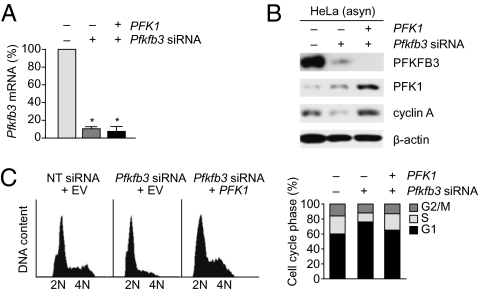

Effect of Overexpression of PFK1 on Proliferation in PFKFB3-Silenced Cells.

Whether overexpression of the downstream glycolytic enzyme 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase (PFK1), which is activated by the product of PFKFB3 activity, could restore entry of PFKFB3-depleted cells into S phase was next investigated. In asynchronously proliferating HeLa cells, 48 h after transfection with Pfkfb3 siRNA, PFKFB3 was efficiently silenced at the mRNA level (∼90% reduction in Pfkfb3 mRNA; Fig. 6A) and at the protein level (Fig. 6B). FACS analysis of the DNA content showed that 48 h after transfection with Pfkfb3 siRNA, the proportion of cells in G1 phase was increased, with a concomitant decrease in the S phase population compared with control cells cotransfected with nontargeting siRNA and empty vector (Fig. 6C). In PFKFB3-silenced cells, the overexpression of PFK1 (∼7,000-fold increase in Pfk1 mRNA levels; Fig. S5) restored the proportion of cells in S phase to that observed in cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 6C). Immunoblotting confirmed that overexpression of PFK1 in PFKFB3-silenced cells restored S phase entry, as indicated by the recovery of the protein level of the S/G2 phase marker cyclin A (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Proliferation is restored in PFKFB3-silenced cells by overexpression of PFK1. (A) qRT-PCR demonstrated that there was ∼90% reduction in Pfkfb3 mRNA levels in PFKFB3-silenced cells 48 h after transfection. (B) Immunoblots from asynchronously proliferating cells 48 h after transfection with nontargeting control siRNA plus empty vector (−/− lane), with Pfkfb3-siRNA plus empty vector or with Pfkfb3-siRNA plus PFK1. (C) Flow cytometry profiles of DNA content (Left) and derived cell cycle phase distribution (Right) 48 h after transfection with nontargeting control siRNA, with Pfkfb3-siRNA, or with Pfkfb3-siRNA plus PFK1. (A) Mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (B; and C, Left) Representative of three independent experiments. (C, Right) Mean of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Our results show that during the cell cycle there is an increase in PFKFB3 protein and activity, which follows a decrease in the action of APC/C-Cdh1. We have previously demonstrated that this ubiquitin ligase degrades PFKFB3 through ubiquitination via recognition of its KEN box consensus motif (11). In synchronized cells, the appearance of PFKFB3 occurs at a critical point in G1, before transition of the cells into S phase, reaching a maximum at ∼8 h following release from nocodazole arrest. The enhanced expression of the gene for the enzyme precedes the appearance of the protein by ∼2 h.

The presence of PFKFB3 is short lasting, ceasing to be detectable 10 h after release from nocodazole and not reappearing at later stages of the cycle. This rapid disappearance is not only due to the transient expression of the gene for PFKFB3 but also to the fact that the enzyme is a substrate for the ubiquitin ligase SCF complexes that mediate the coordinated degradation of a number of cell cycle regulatory proteins and transcription factors (12). SCF is activated by SKP2, β-TrCP, or other F-box proteins (13). We found that β-TrCP increases during late G1/early S phase, concomitantly with the disappearance of PFKFB3, which contains a consensus motif for β-TrCP recognition (268DSGLSS273). When we mutated this motif to alanine residues (268DAGLAA273) the enzyme became resistant to breakdown by SCF. Thus, although during the cell cycle, gene expression is responsible for the generation of PFKFB3, the fine tuning regulating the amount of the protein is provided by posttranslational proteasomal mechanisms, as is the case with the cyclins.

Substrate recognition by SCF-β-TrCP is known to be mediated through a specific phosphorylation event in the target protein (13). A recent study, designed to establish the phosphoproteome associated with cells induced to proliferate (14), identified a distinct phosphorylated residue in PFKFB3 that is not the canonical residue recognized by AMPK or Akt (15). This residue (S273 of the protein) is located within the conserved recognition motif of β-TrCP. We have not carried out a specific mutation of S273; however, it is one of the residues we have mutated to generate PFKFB3 KENWT DSGMUT, which is resistant to degradation by SCF-β-TrCP.

Therefore, because of the combined action of APC/C-Cdh1 and SCF-β-TrCP, PFKFB3 is present only for a short interval, during late G1. Despite its brief appearance in the cell cycle, however, PFKFB3 is essential for its progression, because silencing the protein prevents not only the enhancement of glycolysis but also the transition from G1 to S phase. This is emphasized by the experiments in which cells arrested by glucose starvation can only progress to S phase, following readdition of glucose, if PFKFB3 is present. The obvious function of the enzyme at this stage is to enhance glycolysis because, in cells in which PFKFB3 had been silenced, overexpression of the glycolytic enzyme PFK1 restored the transition into S phase. All these findings indicate that the point in late G1 at which PFKFB3 appears is the nutrient-sensitive restriction point described many years ago (7) and explain the enhanced provision of intracellular glucose at a defined stage of the cycle. Interestingly, the presence of PFKFB3 at other times during the cell cycle is not sufficient for glycolysis to be activated. This is demonstrated by experiments with the mutated enzymes, which not only confirm the kinetics and the degradation routes of the endogenous enzyme but also show that other events, occurring either previously or at the restriction point, are required for PFKFB3 to carry out its metabolic function.

The brief presence of PFKFB3 during the cell cycle raises the question of how the utilization of glucose is coordinated with that of glutamine, an amino acid essential for cell proliferation. We have recently found that glutaminase 1, a critical enzyme in the glutaminergic pathway in cell proliferation, is also subjected to proteasomal degradation by APC/C-Cdh1 (10), suggesting that both glycolysis and glutaminolysis are activated simultaneously at the restriction point.

In conclusion, our results indicate that during cell division the activation of glycolysis is a tightly regulated process. This is achieved by the same mechanisms that dictate the transition from G1 to S, thus providing coordination between cell cycle progression and metabolic supply. The function of this transient enhancement of glycolytic activity in late G1, which is necessary for cell cycle progression, now requires investigation because glycolysis might be used to generate energy, substrates for macromolecular synthesis, or for both purposes. Our present results obtained in a cancer-derived cell line, together with previous studies in a noncancer cell line (9) and in human T lymphocytes (10), suggest that these same, or similar, mechanisms underlie cell proliferation and enhanced metabolism in normal and neoplastic cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Synchronization.

HeLa S3 cells (ATCC; CCL-2.2) were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen). All experiments were carried out at population doublings 6–15. Cell synchronization from G1/S was achieved by release from DTB as described elsewhere (16), with minor modifications. Cells were treated with two sequential 24-h blocks in 3 mM thymidine (Sigma) separated by a 12-h interval without thymidine. Cell synchronization from G2/M was achieved by DTB followed, after 12-h release, by treatment with 100 ng/mL nocodazole (Sigma) for 12 h and release into fresh medium.

Experimental Design.

To address PFKFB3 stability associated with proteasomal degradation, cells were first synchronized by DTB followed by nocodazole arrest and then released for 2 h in nocodazole-free medium before addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG 132 (10 μM). Cells treated with MG 132 were monitored by immunoblotting for 12 h after release from nocodazole and compared with synchronized cells that had not been treated with MG 132.

To determine how PFKFB3 levels are regulated during the cell cycle, a series of mutations in the PFKFB3 KEN box and/or DSG box was generated by site-directed mutagenesis (see RNA Interference). In some experiments these were expressed in synchronized cells in the presence or absence of overexpressed β-TrCP, and the presence of PFKFB3 at 8 h after release from nocodazole was monitored by immunoblotting. In other experiments, the mutated forms were overexpressed in synchronized cells, and the presence of PFKFB3 at different times after release from nocodazole was monitored. The effect of endogenous PFKFB3 on lactate generation and cell cycle stage was then compared with that of overexpressed PFKFB3 in which the KEN box and the DSG box had been mutated. The metabolic activity of this mutated form was verified by demonstrating that it stimulated lactate generation in cells in which Cdh1 had been overexpressed.

To investigate the role of PFKFB3 in cell proliferation, cells were released from DTB at G1/S, transfected with a Pfkfb3 siRNA SMART pool (or nontargeting control siRNA), arrested in mitosis by nocodazole treatment, released into fresh medium, and retransfected with Pfkfb3 siRNA (or nontargeting control siRNA). Cells were harvested at 8 or 12 h after release from nocodazole and subjected to immunoblotting, qRT-PCR and FACS analysis.

In a further set of experiments, cells were deprived of glucose for 72 h by incubation in DMEM without glucose (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours before release from glucose deprivation, the cells were treated with Pfkfb3 siRNA (or nontargeting siRNA) for 24 h and then released in complete medium containing glucose for 18 h, after which they were subjected to immunoblotting, qRT-PCR, and FACS analysis.

In one set of experiments, cells were transfected with PFK1 plasmid (kind gift of Juan Bolaños, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Salamanca, Spain) concomitantly with the addition of Pfkfb3 siRNA and then collected at 48 h posttransfection for immunoblotting and FACS analysis.

Immunoblotting and FACS Analysis.

For immunoblot analysis, cells were harvested and whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysis for 45 min on ice in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) and complete protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) followed by sonication for 10 s. Protein concentration was determined using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Total protein (15–60 μg) was loaded in each lane and separated by 4–20% SDS/PAGE. Protein was transferred from polyacrylamide gels onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) by semidry electroblotting. Blocking, antibody incubations, and washing steps were performed as described (17). Antibodies used for immunoblotting included cyclin E from Novus, Cdh1 from Merck Chemicals, PFKFB3 from Abcam, β-TrCP from Cell Signaling Technology, PFK1 and cyclin A from Insight Biotechnology, and β-actin from Sigma. Generation of PFKFB3v5 antibodies has been described elsewhere (10).

FACS analysis was carried out using the method of Eward et al. (18), with slight modifications. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were pelleted by centrifugation then fixed in 80% methanol at −20 °C for at least 2 h. Methanol was removed by centrifugation and cells were resuspended in PBS containing 50 μg/mL propidium iodide and 50 μg/mL RNase A.

RNA Interference.

PFKFB3 expression was inhibited with double-stranded RNA oligos (siGENOME SMART pool, L-006763–005; Dharmacon). Nontargeting siRNA was used as a negative control. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used in all transfections according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 105 3 d before transfection. The transient transfections were performed using 150 nM of Pfkfb3 siGENOME SMART pool siRNA. siRNAs were complexed with transfection reagent in serum-free and antibiotic-free culture medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated for different times according to individual experimental protocols. All experiments were performed at least three times. Selective silencing of the corresponding genes was confirmed by qRT-PCR and immunoblotting.

i) Plasmids: Cloning of Pfkfb3v5 (accession no. BC040482, Pfkfb3 KENWT DSGWT) and generation of a KEN box-mutated form (Pfkfb3 KENMUT DSGWT) is described elsewhere (10). Site-directed mutagenesis of the DSGXXS box in Pfkfb3 KENWT DSGWT (and Pfkfb3 KENMUT DSGWT) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QuikChange II; Stratagene) using the primer ATCGGGGGCGACGCAGGCCTGGCCGCCCGGGGCAAGAAG (and its reverse and complementary primer; Invitrogen). Underscored nucleotides indicate the mutated amino acids (DSGLSS→DAGLAA). β-TrCP was obtained from Addgene (plasmid 10865) (19). All plasmid DNAs used for transfection were prepared using an EndoFree Plasmid Maxi kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol and confirmed by sequencing.

ii) Cell transfection of HeLa cells: In one set of experiments (Fig. 2C), synchronized cells were transfected using lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions at the time of nocodazole treatment. The total amount of DNA transfected in each experiment was 2 μg, comprising 0.4 μg Pfkfb3 KENMUT DSGWT (or Pfkfb3 KENMUT DSGMUT) plasmid DNA and 1.6 μg β-TrCP plasmid DNA (or empty vector). Cells were harvested for protein extraction 8 h postnocodazole release. In another set of experiments (Fig. 2D), synchronized cells were transfected using lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) at the time of nocodazole treatment. The total amount of Pfkfb3 DNA transfected in each experiment was 0.1 μg. Cells were harvested for protein extraction every 2 h from 0 to 12 h post-nocodazole release.

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR.

To evaluate the efficiency of transfection with Pfkfb3 siRNA, the level of Pfkfb3 mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated using a PureLink Micro-to-Midi kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription reactions using 40 ng of total RNA in a final reaction volume of 20 μL were carried out using SuperScript III Platinum SYBR Green One-Step qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). Relative quantitation data were obtained using the comparative Ct method with Realplex software according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Eppendorf). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used to normalize each of the extracts for amplifiable human DNA. Primers (Table S1) were provided by Eurofins MWG Operon. Cycle conditions are available upon request.

Lactate Determination.

Cell-free supernatant samples were analyzed in triplicate using a lactate kit (Trinity Biotech) adapted for a 96-well plate reader. Briefly, 10 μL of sample or standard were incubated with 100 μL lactate reagent solution for 10 min, after which the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Lactate production (per μg protein) was expressed either as the hourly change in the accumulated amount or as the amount measured at the specified time.

Statistics.

Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Annie Higgs for editorial help in the preparation of this manuscript, Alex Wollenschlaeger for help in preparation of the figures, Ayona Dey for experimental assistance, and Miriam Palacios for technical support and advice. The work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 086729 (to S.M. and S.L.C.) and Cancer Research UK Scientific Program Grant C428/A6263 (to K.S., G.H.W., and S.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1102247108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Vodermaier HC. APC/C and SCF: Controlling each other and the cell cycle. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R787–R796. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagano M. Control of the cell cycle by the ubiquitin system. FASEB J. 1997;11:1067–1075. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.13.9367342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfleger CM, Kirschner MW. The KEN box: An APC recognition signal distinct from the D box targeted by Cdh1. Genes Dev. 2000;14:655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li M, Zhang P. The function of APC/CCdh1 in cell cycle and beyond. Cell Div. 2009;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skaar JR, Pagano M. Cdh1: A master G0/G1 regulator. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:755–757. doi: 10.1038/ncb0708-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King RW, et al. A 20S complex containing CDC27 and CDC16 catalyzes the mitosis-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to cyclin B. Cell. 1995;81:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardee AB. A restriction point for control of normal animal cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1286–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pederson T. An energy reservoir for mitosis, and its productive wake. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:125–129. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almeida A, Bolanos JP, Moncada S. E3 ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Cdh1 accounts for the Warburg effect by linking glycolysis to cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:738–741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colombo SL, et al. Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-Cdh1 coordinates glycolysis and glutaminolysis with transition to S phase in human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18868–18873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012362107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrero-Mendez A, et al. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:747–752. doi: 10.1038/ncb1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: Insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and β-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayya V, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of T cell receptor signaling reveals system-wide modulation of protein-protein interactions. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hue L, et al. Insulin and ischemia stimulate glycolysis by acting on the same targets through different and opposing signaling pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1091–1097. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krude T, Jackman M, Pines J, Laskey RA. Cyclin/Cdk-dependent initiation of DNA replication in a human cell-free system. Cell. 1997;88:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingsbury SR, et al. Repression of DNA replication licensing in quiescence is independent of geminin and may define the cell cycle state of progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eward KL, et al. DNA replication licensing in somatic and germ cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5875–5886. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou P, Bogacki R, McReynolds L, Howley PM. Harnessing the ubiquitination machinery to target the degradation of specific cellular proteins. Mol Cell. 2000;6:751–756. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.