Abstract

The hippocampus is well known for its critical involvement in spatial memory and information processing. In this study, we examined the effect of bilateral hippocampal inactivation with tetrodotoxin (TTX) in an “enemy avoidance” task. In this paradigm, a rat foraging on a circular platform (82 cm diameter) is trained to avoid a moving robot in 20-min sessions. Whenever the rat is located within 25 cm of the robot's center, it receives a mild electrical foot shock, which may be repeated until the subject makes an escape response to a safe distance. Seventeen young male Long-Evans rats were implanted with cannulae aimed at the dorsal hippocampus 14 d before the start of the training. After 6 d of training, each rat received a bilateral intrahippocampal infusion of TTX (5 ng in 1 μL) 40 min before the training session on day 7. The inactivation severely impaired avoidance of a moving robot (n = 8). No deficit was observed in a different group of rats (n = 9) that avoided a stable robot that was only displaced once in the middle of the session, showing that the impairment was not due to a deficit in distance estimation, object-reinforcement association, or shock sensitivity. This finding suggests a specific role of the hippocampus in dynamic cognitive processes required for flexible navigation strategies such as continuous updating of information about the position of a moving stimulus.

Keywords: cognitive map, declarative memory, episodic memory, dynamic environments

Research into the hippocampal role in behavior and cognition is marked by a lasting dichotomy between two major views based on studies on laboratory rodents on one side and studies on human subjects or subhuman primates on the other. Electrophysiological recordings from hippocampus of freely moving rodents showed that many pyramidal neurons act as “place cells” signaling the position of the animal within an environment (1, 2). Based on these findings, the cognitive map theory (3) postulated that the hippocampus provides an allothetic spatial representation of the environment. Further support for this theory came from lesion studies showing detrimental effects of hippocampal lesions on spatial behavior (4–6). However, damage to the hippocampus and surrounding medial temporal lobe structures produce permanent anterograde amnesia for facts and autobiographical events in humans (7). Based on this evidence, the declarative memory theory presumes that the hippocampus is responsible for creating memory representations for these classes of information, which later become hippocampus-independent in a process called systems consolidation (8, 9). This theory is supported by studies on recognition memory (10) and models of amnesia (11) in primates. However, the declarative memory theory does not predict lasting hippocampal involvement in some behavioral tasks such as the spatial water maze (12–16). However, the cognitive map theory does not explain hippocampal role in overtly nonspatial memory tasks (17). In a shadow of these two major theories, minor views claim that the hippocampus is critically important for rapid encoding, long-term storage, and recollection of episodic memories with rich contextual information (18) or automatic recording of attended experience (19). These views are based on the fact that the hippocampus is critical for rapid encoding of unique, one-trial memories (20) and that it allows “latent” learning of background (contextual) information in the absence of explicit learning requirement (21).

We aim to test these disparate views by studying the effect of hippocampal inactivation on flexible navigation in dynamic environments. Unlike the vast majority of laboratory tests of spatial cognition, real world environments are dynamic and ever-changing. For instance, considering the movement of objects in the environment in planning one's own locomotion is an important cognitive ability of virtually all vertebrates, because conspecific animals, predators, or prey animals represent crucial components of their natural environments. It is likely that this motility poses specific requirements, which are not addressed by standard laboratory spatial tests and which may be critical for our understanding of the role of the hippocampus. Some aspects of such “dynamic environments” were addressed previously in navigation tasks on a continuously rotating circular arena with a goal location defined in stationary room coordinates (22–24). To take the problem even further, we have designed a unique “enemy avoidance task,” where subject rats foraging for barley grains were trained to avoid a conspecific—an “enemy” rat (25)—by administering a mild electric foot shock to the subject rat whenever the distance between the two animals dropped to <25 cm. The results have shown that rats are capable of avoiding a moving object while actively foraging on the arena.

In this study, we tested the effect of inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus on the ability of rats to avoid a moving object. We used a modified version of the enemy avoidance task, where the enemy rat was replaced with a more neutral and predictably acting object, a programmable mobile robot. The use of a robot also allowed testing both moving-object and stable-object conditions. Rats were trained to avoid either a mobile (n = 8) or a stable (n = 9) robot for 6 d in 20-min sessions. On day 7, their dorsal hippocampus was bilaterally inactivated by intrahippocampal infusion of tetrodotoxin (TTX; 5 ng in 1 μL per hemisphere) via chronically implanted guide cannulae 40 min before the session. On day 8, the rats received infusion of vehicle instead of TTX 40 min before the last session. The Cognitive Map theory predicts no effect of the inactivation in this task, because navigation to visible targets should not depend on the hippocampus (3, 4). The level of impairment predicted by the Declarative Memory theory depends on the extent to which the memory could have consolidated outside the hippocampus, but should be the same for both mobile and stable versions. In contrast to both of these theories, the TTX inactivation severely impaired avoidance of the moving robot, whereas the ability to avoid the stable robot was unaffected. Neither distance estimation nor object-reinforcement association or shock sensitivity can explain this disparity. Instead, these results suggest that the hippocampus plays a critical role in dynamic cognitive processes required for flexible navigation strategies such as continuous updating of information about the position of a visible moving stimulus. Our data cannot be explained by the hippocampus being involved in mapping stationary space or by being temporarily involved in long-term declarative memory formation. Rather, it suggests that the hippocampus is critically important for rapid and continuous updating of the memory of one's own experience in a dynamic world.

Results

Effect of Hippocampal Inactivation on Enemy Avoidance.

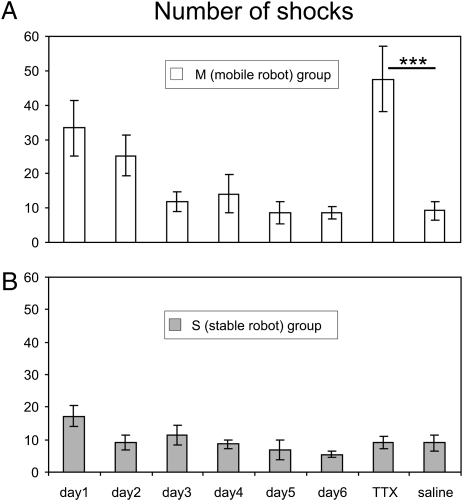

Rats learned to avoid the moving robot (M group) over the 6 d of training. Inactivating the hippocampus by TTX on day 7 abolished the avoidance (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the vehicle infusion on day 8 did not affect the avoidance. The one-way ANOVA on the number of shocks found a significant effect of days (F(7, 49) = 7.74, P < 10e−5). The post hoc tests showed that avoidance was asymptotic from day 3 (day 1 > days 3–6 and day 8, saline session) and that on day 7 (TTX), performance was reduced to the level of day 1 (significantly worse than all other sessions). Similarly, rats learned to avoid a stable robot well (S group; F(7, 56) = 2.30, P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). However, in this case, inactivation had no effect on the avoidance. The post hoc test showed that the number of foot shocks decreased over days (day 1 > days 2, 5, and 6) and neither the TTX infusion on day 7 nor the saline infusion on day 8 had any effect on avoidance.

Fig. 1.

The effect of hippocampal inactivation on Enemy Avoidance (shown as the average number of shocks ± SEM). (A) Avoidance of a moving robot (M group). Bilateral inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus by infusion of TTX on day 7 significantly increased the number of shocks received as a result of the robot approaches compared with vehicle infusions on day 8, (***P < 0.00001). (B) Avoidance of a stable robot (S group). The robot was turned off in this version of the task, but it was moved to a different position by the experimenter in the middle of each training session. In this case, hippocampal inactivation had no effect on the avoidance.

Effect of Hippocampal Inactivation on Locomotion.

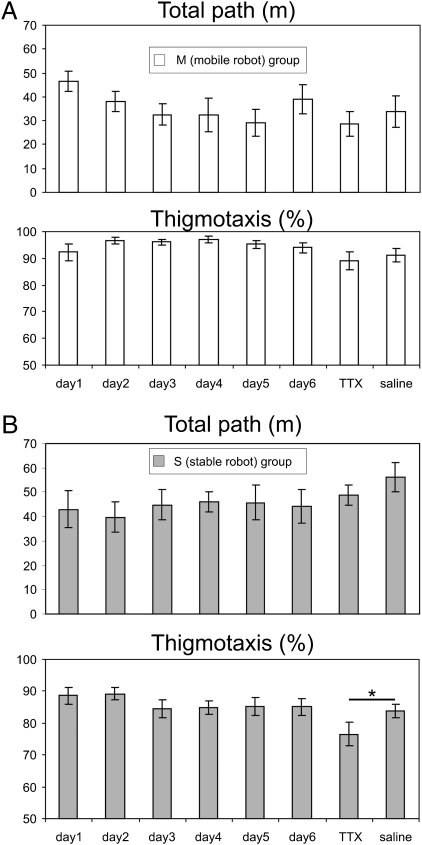

Locomotion patterns varied during the course of the experiment. The one-way ANOVA on the total path traveled during a session found a significant effect of days in the M group (F(7, 49) = 2.29, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). The post hoc tests showed that rats walked less on days 5 and 7 compared with day 1 (both P values <0.05), but not relative to day 8 (vehicle infusions). The one-way ANOVA also found a significant effect of days on thigmotaxis in the M group (F(7, 49) = 2.28, P < 0.05), but the post hoc tests failed to find significant differences between any two sessions. In the S group, the one-way ANOVA found no effect of days on the total path (F(7, 56) = 1.81, P > 0.05; Fig. 2B), but it found a significant effect of days on thigmotaxis (F(7, 56) = 2.99, P < 0.01). The post hoc test found that thigmotaxis was reduced in the TTX session on day 7 compared with all other sessions (all P values <0.05). These results suggest that hippocampal inactivation partially alleviated the border-escaping response to a stressful stimulus. However, this effect was nonsignificant when avoiding a moving robot.

Fig. 2.

The effect of hippocampal inactivation on locomotor behavior shown as the average total path length (m ± SEM) and average level of thigmotaxis (% ± SEM). (A) Avoidance of a moving robot (group M). Hippocampal inactivation by TTX on day 7 did not significantly alter the overall locomotion or thigmotaxis compared with vehicle infusion on day 8. (B) Avoidance of a stable robot (S group). Hippocampal inactivation by TTX on day 7 did not influence the overall locomotion. The level of thigmotaxis was moderately, but significantly, decreased (i.e., the animals tended to spend more time in the central part of the arena) after the TTX infusion compared with the vehicle infusion on day 8 (*P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that rodent hippocampus is necessary to avoid a moving target, but not a stable one. This finding is not predicted by the cognitive map theory and the declarative memory theory and supports the idea that the hippocampus provides for rapid encoding and updating of memory of one's own experience.

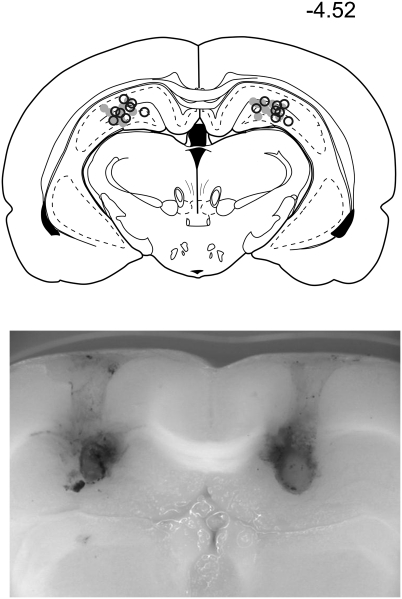

Spared avoidance of the stable robot rules out the possibility that the impairment was due to a deficit in distance estimation, object-reinforcement association, or sensitivity to the foot shock. The possibility that the impairment could be due to the slightly reduced locomotion on day 7 in the M group is unlikely because a similar reduction had no effect on the avoidance on day 5 and no such reduction was observed in the S group, even though it could have facilitated the avoidance in that version. Instead, the rats were well-motivated to forage in the arena and they covered substantial distances during the sessions (Fig. 2), but they still visited the relatively large (up to 37% of the arena surface) foot-shock area scarcely. In addition, histological control (Fig. 3) showed that the infusion sites were located exclusively within the dorsal hippocampus, and the ink infusions did not suggest spread of the inactivating agent to neighboring brain areas. Therefore, we assume that the reduced locomotion was a result, rather than a cause, of the inability to avoid the shock. The possibility that the animals trained in the stable-robot version could associate the foot-shock area with some stable arena-bound cues was ruled out by moving the robot to a different place in the middle of each session. The lower number of shocks received by rats avoiding the stable robot opened the possibility that the moving robot avoidance was impaired simply because it was more difficult and, therefore, put more demand on hippocampal function, whereas the stable robot could be avoided by hippocampus-independent strategy such as general inhibition of locomotion. However, the locomotion in the stable robot variant did not change during the course of the training despite the decrease in the number of shocks. Importantly, there was also no decrease in locomotion after the TTX infusion on day 7, indicating that the spared stable robot avoidance was not due to a general inhibition strategy. Hippocampal role in distance estimation in rats has been examined in only a few studies by using the go/no-go procedure (26, 27), and the present work provides another piece of evidence that the hippocampus is not necessary for distance information processing.

Fig. 3.

Histological control of the infusion site placement in the hippocampus. (Upper) End of tracks of infusion cannulae (M group, black circles; S group, gray circles) were verified postmortem on coronal brain sections (adapted from Paxinos and Watson; ref. 39). (Lower) Image of a representative brain slice. The extent of the tissue affected by the TTX infusion was estimated by using infusions of black ink in the same volume as the TTX infusions. The ink blots showed no signs of excessive extrahippocampal leakage.

The notion that navigation to visible goals, in contrast to navigation to unmarked places defined solely by their relationships to distant landmarks, does not depend on hippocampal function is one of the basic assumptions of the cognitive map theory (3, 4). This view predicts that avoiding a visible goal will not be affected by hippocampal dysfunction. Our finding that hippocampal inactivation produced no deficit in the enemy avoidance task as long as the robot was stable is thus in agreement with this view. However, the cognitive map theory did not specifically address navigation relative to moving objects. The severe deficit of the avoidance of the moving robot induced by the inactivation suggests that direct visibility of the goal is not the only decisive factor, which makes a spatial task hippocampus-dependent, and calls for a revision of the cognitive map theory.

Hippocampal neurons recorded from freely moving rats respond to various manipulations of spatial cues including rotation, translation, and gradual transformation of cue arrays in the environment (28–30, 32). Several studies recorded hippocampal single unit activity from rats that pursued visible moving objects in the environment (33, 34). These studies found no explicit coding for position of the moving object in the hippocampal unit activity. However, in these behavioral paradigms the moving objects were directly associated with reward, and the task was not shown to be hippocampus-dependent. We argue that our Enemy Avoidance task is far more demanding in terms of motion planning and prediction of future positions of a punishment-associated moving object than pursuit of a visible reward-associated cue, which may be based on simple stimulus-response association learning. The control spatial cues exert over place cell firing may depend on the cognitive requirements of the behavioral task (35). Therefore, it is possible that under different circumstances, hippocampal neurons may signal positions of moving objects.

Stress affects memory (35) and modulates functional connectivity between the hippocampus and the rest of the brain (36). Moreover, hippocampal lesions have been reported to have anxiolytic effect (37). If the moving robot version of the enemy avoidance task was associated with an increased level of stress compared with the stable robot version, the impaired avoidance of the moving robot could be explained by reduced stress during the inactivation session. However, in addition to the increased number of shocks, the reduced stress would also be expected to reduce thigmotaxis and increase overall locomotion, neither of which was observed in the moving robot version. Therefore, we consider the possibility that increased stress was responsible for the effect of the inactivation unlikely.

Avoiding a moving target in the enemy avoidance task requires the animals to pay almost unceasing attention to the visible target and continuously update their position relative to that target. Similarly, continuous updating of one's own position relative to stable visible distal cues is crucial for navigation to an invisible target, which is typical for most hippocampus-dependent spatial tasks, such as the Morris water maze. We suggest that visibility of the target is not the sole decisive factor and that in addition to invisibility of the target, it is the need for continuous updating that may itself be sufficient to make a task hippocampus-dependent. This view of hippocampal function is closest to a theory describing the role of the hippocampus in behavior as automatic recording of attended experience (19) and emphasizing the importance of the hippocampus in memory of one's own experience.

Methods

Animals.

Seventeen young adult (3 mo) male Long-Evans rats from the Institute of Physiology's breeding colony weighing 300–400 grams were used in this study. They were housed in pairs in transparent Plexiglas cages and maintained at 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 0700 hours. All behavioral testing was conducted between 1200 hours and 1800 hours. All animal treatment complied with the Czech Animal Protection Act, European Union directive 86/609/EEC, and National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Surgical Procedures.

Fourteen days before the start of behavioral training, the rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) and mounted in a Kopf stereotaxic apparatus. Two holes (1 mm in diameter) were drilled at AP −4.5, ML ± 3.0 relative to bregma. The use of these coordinates was based on laboratory experience and histological feedback. Two cannulae (0.7 mm in diameter) were stereotaxically lowered through the openings to extend 2.5 mm below the skull surface and fixed to the skull with dental cement. Two set screws were tapped in the skull to anchor the dental cement. The wound was sutured and a local antiseptic was applied to prevent infection. The animals were left to recover 14 d after the surgery.

Hippocampal Inactivation.

The animals were given one bilateral infusion of TTX, a potent blocker of voltage-gated sodium channels, 1 d before the onset of behavioral training to habituate them to the inactivation procedure. Forty minutes before the inactivation session on day 7 of the avoidance training, 5 ng of TTX in 1 μL of physiological saline was manually infused into each hippocampus during 1 min via an infusion cannula (0.45 mm o.d.) attached to a 5-μL Hamilton syringe by polyethylene tubing. The tip of the infusion needle protruded from the guide cannula by 1 mm, so that total distance of the infusion site from the skull surface was 3.5 mm. The infusion cannula was left in place for another minute after the infusion before it was slowly withdrawn. The same procedure was used to infuse 1 μL of saline 40 min before the control session on day 8.

Experimental Apparatus.

The apparatus was an elevated circular platform (82 cm diameter) circumscribed by a 50-cm-high opaque wall eliminating disturbing stimuli from the room. The arena floor was made of electrically grounded fine wire mesh. An overhead infrared camera mounted on the ceiling monitored two light-emitting diodes: a smaller one, attached by a plastic strap to the back of the rat and a larger one, attached to the robot (see description below). A centrally placed overhead feeder dispersed barley grains to random locations on the arena surface in 10-s intervals. A computer-controlled system delivered a mild electric foot shock (0.2–1.2 mA; AC; 50 Hz; 500 ms) whenever the distance between the rat and the center of the robot dropped to <25 cm for at least 100 ms. If the distance did not increase within 500 ms following the foot shock, additional shocks were delivered every 500 ms, until the rat “escaped” away from the robot. To adjust to individual variability in sensitivity to the foot shock, its intensity was set individually for each rat as the lowest value eliciting escape response, but not freezing. Shocks were delivered through a shock-delivering cable connected to the implanted low-impedance s.c. needle by an alligator clip and grounded arena floor. Because the highest voltage drop was between the rats’ paws and the floor, the animals most likely perceived the shock at their paws. This shocking procedure was established in place avoidance studies and has been demonstrated to be safe, effective, and to produce reliable avoidance behavior (38).

The robot used in this study was a custom-made electronic device controlled by a programmable integrated circuit. Basic construction consists of an aluminum chassis with two traction wheels on the sides of the robot, each driven by an independent electric actuator. The construction was weight-balanced and equipped with a small unpowered front wheel to ensure stability. Both traction wheels ran at equal speeds, but during turns their directions were opposite. The robot was equipped with three sensors. Two opto-isolators were attached to the wheels controlling speed and distance, and a microswitch was added to a retractive front bumper. Once the bumper hit the wall of the arena, the switch was activated. Such a hit could be followed by a user-defined period of inactivity (we used 15 s to ease the task moderately). The robot then moved 10 cm backward, turned at a random angle and ran forward until hitting the wall again. The range of chosen angles could be limited by operating personnel (we used angles between 90° and 270°). The controls consisted of speed selectors between seven speed levels 4–28 cm/s, program switches and a remote-controlled/self-directing mode switch. Inner parts and controls were protected by a removable fitting cover made of aluminum plate. A large diode was placed on the top of the robot for tracking purposes. Power was provided by five rechargeable AA type batteries. The robot was 17 cm long, 16 cm wide, and 12 cm high.

Behavioral Procedures.

Three days before the onset of the behavioral procedures, the rats were food-restricted to maintain them between 85% and 90% of prerestriction body weight to motivate foraging. Water was available ad libitum throughout the experiment. The rats were fed only after their daily experimental sessions. The rats were habituated to the arena and trained to forage for the barley grains in two daily 20-min habituation sessions. Rats were randomly assigned to two groups with either a mobile (M, n = 8), or a stable robot (S, n = 9). A hypodermic needle was implanted s.c. by piercing the rat's skin between its shoulders, and creating a small loop on the needle with hemostat forceps to allow administration of mild electric shocks. The loop prevented the needle from slipping out and provided purchase for an alligator clip connecting a shock-delivering cable. The animals were then trained to avoid the robot at a distance of at least 25 cm from its center (Enemy Avoidance task). The avoidance was reinforced by mild electric foot shocks. The robot was programmed to move straight forward by 10 cm/s until it hit the wall, then it waited for 15 s, turned at a random angle between 90 and 270°, and ran forward again (M group; n = 8). For some rats (S group; n = 9), the robot was switched off and placed at the border of the arena, with its front part facing the wall. After the first 10 min, the robot was transferred by the experimenter to the opposite part of the arena. The avoidance training took a total of eight sessions on eight consecutive days. The hippocampal inactivations by bilateral intrahippocampal TTX infusions occurred on day 7, and saline was infused on day 8.

Histology.

After termination of the behavioral procedures, the animals were deeply anesthetized by ketamine and black ink was injected via the implanted guide cannulae by using the same procedure as used for the TTX injections to verify localization of the infusion sites. The animals were then transcardially perfused with saline and subsequently with 4% formaldehyde solution. Brains were removed, saturated in 30% sacharose overnight, frozen, and sectioned in 50-μm coronal sections. Every tenth section was stained with cresyl violet, and the locations of the infusion sites were verified (Fig. 3).

Evaluated Parameters and Statistical Analysis.

Avoidance was evaluated as the total number of shocks per session received as a result of the robot approaches. Because increased anxiety may interfere with avoidance by decreasing overall locomotion and altering spatial distribution by increasing the tendency to stay near the wall (thigmotaxis), we also measured the total path traveled during a session and the level of thigmotaxis. Thigmotaxis was assessed by dividing the arena into an inner circle and an outer annulus with equal surfaces and using the proportion of time spent in the outer annulus as a measure of thigmotaxis. Within-subject one-way ANOVA with repeated measures on days was used to evaluate the effect of the inactivation on the avoidance. Newman–Keuls post hoc tests were used as appropriate. All significances were accepted at level α = 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pavel Jiroutek for the design and assemblage of the robot. This study was supported by Czech Science Foundation Grants 309/09/0286, P303/10/J032, and P303/10/P191, Grant Agency of the Academy of Sciences Grant KJB500110904, Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports Center Grants 1M0517 and LC554, and by Marie Curie Reintegration Grant PIRG-GA-2009-256581. P.T. and K.B. were partially supported by Grantová Agentura České Republiky Grant 206/05/H012.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.O'Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science. 1993;261:1055–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.8351520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Keefe J, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford: Clarendon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O'Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297:681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce JM, Roberts AD, Good M. Hippocampal lesions disrupt navigation based on cognitive maps but not heading vectors. Nature. 1998;396:75–77. doi: 10.1038/23941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ, Hill CR, Rudy JW. Damage to the hippocampal formation in rats selectively impairs the ability to learn cue relationships. Behav Neural Biol. 1989;52:331–356. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(89)90457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Squier LR, Cohen NJ. Human memory and amnesia. In: Lynch G, McGaugh JL, Weinberger NM, editors. Neurobiology of learning and memory. New York: Gilford; 1984. pp. 3–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squire LR, Alvarez P. Retrograde amnesia and memory consolidation: A neurobiological perspective. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaffan D. Recognition impaired and association intact in the memory of monkeys after transection of the fornix. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;86:1100–1109. doi: 10.1037/h0037649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishkin M. Memory in monkeys severely impaired by combined but not by separate removal of amygdala and hippocampus. Nature. 1978;273:297–298. doi: 10.1038/273297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland RJ, et al. Retrograde amnesia after hippocampal damage: Recent vs. remote memories in two tasks. Hippocampus. 2001;11:27–42. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2001)11:1<27::AID-HIPO1017>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark RE, Broadbent NJ, Squire LR. Impaired remote spatial memory after hippocampal lesions despite extensive training beginning early in life. Hippocampus. 2005;15:340–346. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin SJ, de Hoz L, Morris RG. Retrograde amnesia: Neither partial nor complete hippocampal lesions in rats result in preferential sparing of remote spatial memory, even after reminding. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:609–624. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broadbent NJ, Squire LR, Clark RE. Reversible hippocampal lesions disrupt water maze performance during both recent and remote memory tests. Learn Mem. 2006;13:187–191. doi: 10.1101/lm.134706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teixeira CM, Pomedli SR, Maei HR, Kee N, Frankland PW. Involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in the expression of remote spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7555–7564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1068-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez P, Wendelken L, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampal formation lesions impair performance in an odor-odor association task independently of spatial context. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:470–476. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winocur G, Moscovitch M, Sekeres M. Memory consolidation or transformation: Context manipulation and hippocampal representations of memory. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:555–557. doi: 10.1038/nn1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris RG, Frey U. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity: Role in spatial learning or the automatic recording of attended experience? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;352:1489–1503. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Modality-specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science. 1992;256:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matus-Amat P, Higgins EA, Barrientos RM, Rudy JW. The role of the dorsal hippocampus in the acquisition and retrieval of context memory representations. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2431–2439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cimadevilla JM, Fenton AA, Bures J. New spatial cognition tests for mice: Passive place avoidance on stable and active place avoidance on rotating arenas. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54:559–563. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wesierska M, Dockery C, Fenton AA. Beyond memory, navigation, and inhibition: Behavioral evidence for hippocampus-dependent cognitive coordination in the rat. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2413–2419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3962-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubík S, Stuchlík A, Fenton AA. Evidence for hippocampal role in place avoidance other than merely memory storage. Physiol Res. 2006;55:445–452. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telensky P, et al. Enemy avoidance task: A novel behavioral paradigm for assessing spatial avoidance of a moving subject. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;180:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long JM, Kesner RP. The effects of dorsal versus ventral hippocampal, total hippocampal, and parietal cortex lesions on memory for allocentric distance in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:922–932. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.5.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long JM, Kesner RP. Effects of hippocampal and parietal cortex lesions on memory for egocentric distance and spatial location information in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:480–495. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller RU, Kubie JL. The effects of changes in the environment on the spatial firing of hippocampal complex-spike cells. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1951–1968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotenberg A, Muller RU. Variable place-cell coupling to a continuously viewed stimulus: Evidence that the hippocampus acts as a perceptual system. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;352:1505–1513. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knierim JJ, Rao G. Distal landmarks and hippocampal place cells: Effects of relative translation versus rotation. Hippocampus. 2003;13:604–617. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leutgeb JK, et al. Progressive transformation of hippocampal neuronal representations in “morphed” environments. Neuron. 2005;48:168–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trullier O, Shibata R, Mulder AB, Wiener SI. Hippocampal neuronal position selectivity remains fixed to room cues only in rats alternating between place navigation and beacon approach tasks. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4381–4388. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho SA, et al. Hippocampal place cell activity during chasing of a moving object associated with reward in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;157:254–270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zinyuk L, Kubik S, Kaminsky Y, Fenton AA, Bures J. Understanding hippocampal activity by using purposeful behavior: Place navigation induces place cell discharge in both task-relevant and task-irrelevant spatial reference frames. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3771–3776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050576397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ježek K, et al. Stress-induced out-of-context activation of memory. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segal M, Richter-Levin G, Maggio N. Stress-induced dynamic routing of hippocampal connectivity: A hypothesis. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1332–1338. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNaughton N, Gray JA. Anxiolytic action on the behavioural inhibition system implies multiple types of arousal contribute to anxiety. J Affect Disord. 2000;61:161–176. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuchlik A, Rezacova L, Vales K, Bubenikova V, Kubik S. Application of a novel Active Allothetic Place Avoidance task (AAPA) in testing a pharmacological model of psychosis in rats: Comparison with the Morris Water Maze. Neurosci Lett. 2004;366:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paxinos G, Watson CR. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 5th Ed. San Diego: Elsevier Academic; 2003. [Google Scholar]