Spina bifida occulta (described by von Recklinghausen in 1886 [7] and republished in this issue [8]) is likely one of the most frequent growth defects, but is reported with a quite variable incidence from 5% [6] to 55% of the population [3], based on radiographic and cadaveric surveys. The estimates seem to vary by the age of the study population, the country (and perhaps ethnic groups or races), and the period of time in which the data are collected, but recent estimates are 10% to 20% of the US population [1]. In almost all cases, the abnormality itself is asymptomatic. It reportedly occurs with increased frequency in areas with high fluorosis [2] (44% versus 12% in controls in India). Sarpyenar, in 1947, suggested spina bifida occurred with higher frequency in patients with other conditions, such as Legg-Calvé-Perthes (LCP) disease, “dystrophia subluxant” (congenital subluxation of the hip), coxa vara, and Osgood-Schlatter disease [5].

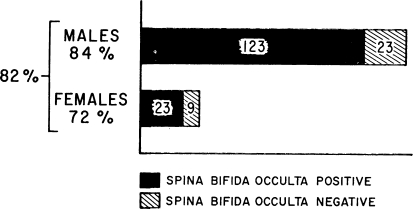

A few years later, Katz found 82% of patients with LCP disease in his study group had spina bifida occulta [4]. The most common location was S1, but the condition occurred at other spinal levels (Table 1). Interestingly, the condition occurred with far higher frequency in boys than in girls with LCP disease (Fig. 1). However, Katz concluded his data did not show a high association: “The evidence of such an association is wholly inconclusive when one considers that in normal children studies have shown similar incidences of spina bifida occulta.” (Katz did not, however, cite data from those other studies: it was common at the time to make general statements as fact without documentation. Today’s rigorous standards of reporting would require such documentation.) To support his conclusion, Katz followed 64 of his patients and noted, as they aged, the incidence decreased as the spine matured: at last followup only 55% of these individuals had obvious spina bifida occulta.

Table 1.

Forms of spina bifida occulta in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

| No. of cases | Percentage age | |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | 54 | 37 |

| S1–S2 | 24 | 16 |

| L5–S1 | 14 | 9 |

| L5 | 12 | 8 |

| S1–S2–S3 | 10 | 7 |

| L5–S1–S2 | 6 | 4 |

| S1–S2–S3–S4–S5 | 5 | 3 |

| Other asorted combinations | 21 | 16 |

| Total | 146 |

(Reprinted with permission and ©Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, from Katz JF. Spina bifida occulta in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1959;14:110–118.)

Fig. 1.

Incidence of spina bifida occulta in Legg-Calvé Perthes disease. (Reprinted with permission and ©Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, from Katz JF. Spina bifida occulta in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1959;14:110–118.)

Katz’s report illustrates several important points. First, it is frequently difficult to establish associations of conditions. The incidence of one or both conditions may widely vary with race, geography (with varying environmental factors in addition to race or ethnic group), or age. Second, Katz refuted an earlier argument of an association based on the fact that a previous author had not accounted for the changing incidence of apparent spina bifida occulta with age. Limitations of studies are important to explore, and Sarpyenar [5] apparently did not consider this important limitation in his study. Third, standards of reporting change. Today, statements of “fact” require documentation.

References

- 1.Anonymous. Spina bifida occulta. 2009. Spina Bifida Association. Available at: http://www.spinabifidaassociation.org/site/c.liKWL7PLLrF/b.2700275/k.5F64/Spina_Bifida_Occulta.htm. Accessed January 13, 2011.

- 2.Gupta SK, Gupta RC, Seth AK, Chaturvedi CS. Increased incidence of spina bifida occulta in fluorosis prone areas. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1995;37:503–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1995.tb03363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hintze A. Enuresis, spina bifida occulta and epidural injections. Mitt Grenzgeb Med Chir. 1922;35:484–543. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz JF. Legg-Calve-Perthes disease; results of treatment. Clin Orthop. 1957;10:61–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarpyener MA. Spina bifida aperta and congenital stricture of the spinal canal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1947;29:817–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutow WW, Pryde AW. Incidence of spina bifida occulta in relation to age. AMA J Dis Child. 1956;91:211–217. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1956.02060020213001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recklinghausen F. Untersuchungen über die Spina bifida. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1886;105:243–330. [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Recklinghausen F. The classic: studies on spina bifida. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1729-2 (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]