Abstract

Objective

This study aims to perform an evidence-based review on the quantitative data regarding coping processes related to posttraumatic growth in the field of oncology to facilitate understanding of posttraumatic growth in oral cavity cancer (OCC) patients.

Material and methods

Pubmed, Medline, and PsycINFO were used for the search and the reference list checked for each selected article. Full articles meeting the inclusion criteria were retrieved. Only English articles were included.

Results

The initial search yielded 934 publications; 64 “potentially relevant papers” and 21 “effective” papers formed the basis of this review. Personality traits and social support lead to development of positive coping methods in cancer patients. Overriding influences are benefit finding and meaning making. Specific coping processes were identified to be significantly associated with posttraumatic growth in patients suffering from different cancers and a need for additional prospective research regarding specific processes and outcomes among oral cavity cancer patients. A proposed theoretical model based on the evidence of management of other cancer research fields is suggested for patients with OCC.

Conclusion

An evidence-based review of coping strategies related to posttraumatic growth was performed which identified key coping strategies and factors that enhance coping processes. A conceptual model of coping strategies to enhance posttraumatic growth in OCC patients based on the scientific evidence attained is suggested to provide a more holistic approach to OCC management.

Keywords: Coping process, Posttraumatic growth, Cancer, Oral cavity, Oncology

Introduction

Posttraumatic growth (PTG) refers to positive psychological changes and growth beyond previous levels of functioning and thereby implies both an outcome and a process (struggle after a traumatic event) [1, 2]. PTG starts when a severe adverse life event challenges or shatters the person’s cognitive scheme of the world and him or herself such as cancer diagnosis. The subsequent growth represents the outcome due to coping processes being employed to adapt first to the event and secondly to use to create a more positive revised world view [2]. In literature, an attempt has been made to differentiate between PTG as an outcome and PTG as a coping strategy in terms of positive illusions that might help people counterbalance emotional distress. The same authors, however, concluded that such differentiation is only for ontological purpose [1].

Coping refers to cognitive and behavioral efforts to master, reduce, or tolerate the internal and external demands of the stressful encounter [3]. Coping has two major functions: dealing with the problem causing the distress (problem-focused coping) and regulating emotions (emotion-focused coping) [3]. Recently, researchers have begun to investigate psychological mechanisms or pathways potentially contributing to PTG and it has been suggested that coping strategies are key components of the pathway to PTG [3, 4]. Taylor and Armour [5] who reviewed the literature of coping strategies with an array of normal stressful events and those dealing with extreme stressful events like cancer, heart disease, and HIV infection implied that individuals who are capable of developing positive coping processes can adapt significantly better. Although coping strategies are increasingly recognized as important in cancer management, understanding “the process” and “outcomes” of the strategies are complex and fragmented and thus have hampered the implementation of coping strategies interventions in cancer management [1]. The aims of this paper were to perform an evidence-based review of the cancer literature focusing on PTG in order to identify positive coping processes being probably also relevant for oral cavity cancer (OCC) patients. Identifying such processes may be important to devise theoretical and conceptual models to implement coping strategies within OCC. Such frameworks may act as a guide to develop interventional studies in the field of OCC.

Materials and methods

The search strategy was designed in consultation with a senior librarian. The electronic databases used were Pubmed, Medline, and PsycINFO. The search was done using the following keywords from the earliest year available to December 2010:

(#1) AND (#2) AND (#3)

-(posttraumatic growth*) OR (stress-related growth*) OR (posttraumatic growth inventory)

-(coping processes)

-(cancer) OR (oncolog*)

A combination of free text terms with Boolean operators and truncation were used. No restrictions were placed on the year of publication; however, only papers in English were included. It was decided that all papers measuring PTG in cancer patients to be included in the initial search. The citations retrieved from each database were exported to the EndNote® X3 (Thomson Reuters; Carlsbad, CA, USA) bibliographic management software. Duplicates were removed. The abstracts of all articles related to PTG were screened. The abstracts of all articles were independently screened by two of the review authors (Rajandram Rama Krsna (RRK) and Roger Arthur Zwahlen (RAZ)).

Guidelines, dissertations, theses, handbooks, commentaries, review articles, expert opinions and case reports, as well as trials with less than ten subjects in either intervention group were excluded. Disagreement between the review authors (RRK and RAZ), was resolved by consensus or consultation with a third party (Colman McGrath). This identified “potentially relevant articles”. Full articles of “potentially relevant articles” were obtained and appraised critically to identify “effective papers”.

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied:

Clinical studies related to PTG in adult (>18 years) cancer patients.

Quantitative assessment of PTG using standardized validated instruments: “Posttraumatic Growth Inventory” [32], the “Stress-Related Growth Scale” [21], the “Changes in Outlook Questionnaire” [10], and “Perceived Benefit Scales” [18].

Assessment of coping methods related to PTG

Studies of less than ten subjects were excluded

The reference list of all selected articles was manually searched for any related articles to determine any additional papers (“reference linkage”). These identified “effective papers” formed the basis of the review.

The “effective papers” were assessed critically in the next stage and the following information was collected:

Study design

Socio-demographics of the study group

Method of assessing PTG

PTG as an outcome

Time period of assessment

Domains of PTG affected

Coping Processes related to development of PTG

Results

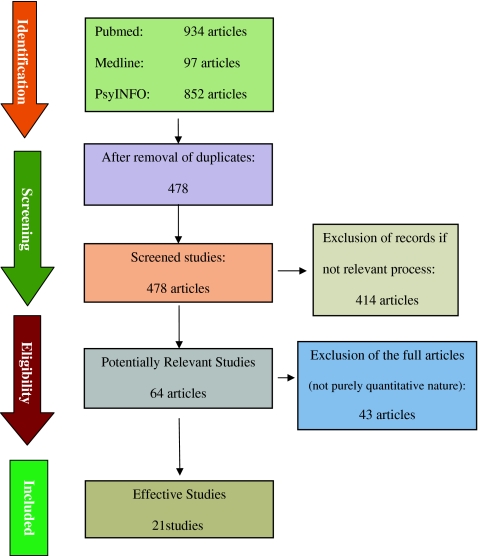

The initial search yielded 934 publications and after removing duplicate publications 478 abstracts were screened. Among these, 414 publications were excluded (guidelines, reviews, commentaries, case reports, etc.) thus identifying 64 “potentially relevant publications”. Full-text articles of these 64 publications were obtained and subsequently 43 publications were excluded as they did not focus on adult cancer patients; were not primarily concerned with PTG; did not use standardized instruments for assessing PTG; and/or reported on less than 10 subjects; and did not use purely quantitative methods for assessing coping processes. Twenty one papers were deemed as “effective publications” which formed the basis of this review. A PRISMA flow chart [6] of the search process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of records identification and selection

No randomized control trial was found among the effective papers; 16 papers were cross sectional studies and five papers were longitudinal studies. Table 1 provides detailed characteristics of this review’s studies including type of study, type of cancer population studied, mean age, and duration of assessment and coping processes that showed significant association with PTG. The number of patients in each study varied greatly. Analysis of the patient’s age showed that the majority of patients were between 50 and 70 years age (14 studies). There were 10 studies on breast cancer patients, seven studies on heterogeneous groups of cancer patients, one study each for patients with prostate cancer, cervical cancer, bone marrow transplant, and oral cavity cancer. There was a vast difference in the time at which assessment of coping methods or PTG were conducted. Some of the studies started the PTG assessment based on time since diagnosis (11 studies) whereas others studies reported their data based on time from treatment (nine studies). The results from our review found that there were specific positive coping processes being significantly related to PTG as well as overriding factors that directed these patients to use those positive coping processes namely personality traits, social support, as well as benefit finding and meaning making.

Table 1.

Findings from studies included in this review

| Author/C.P | T | M.A (y) | Assessment (months) | Coping process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ho et al. 2010 (OC) | C | 60 | 6 PT | Hope α PTG (r = 0.49, p < 0.01) |

| Optimism α PTG (r = 0.31, p < 0.05) | ||||

| Marital support α PTG (p < 0.05) | ||||

| Lelorain et al. 2010 (BC) | C | 65.0 | 5 PD | Positive affectivity PTG (β = 0.39, p < 0.01) |

| Active (β.16, p < 0.05), positive, relational, religious coping α PTG (β = 0.19, 0.23, 0.24, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Zwahlen et al. 2010 (H)a | C | Pt: 59.5 PR: 60.0 | 18 PT | Strong marital support α PTG (p < 0.05) |

| Scrignaro et al. 2010 (H) | L | 52.0 | T1: any time PD T2: 6 after T1 | Active coping, planning, and self distraction α |

| PTG (r = 0.51, 0.50, 0.41, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Problem focused coping increased PTG (p < 0.001) | ||||

| Thombre et al. 2010 (H) | C | 55.7 | 6 PT | Meaning making α PTG (0.32, p < 0.05) |

| Benefit finding α PTG (0.40, p < 0.01) | ||||

| Thombre et al. 2010 (H) | C | 39.8 | 11.5 PD | Religious appraisal α PTG (β = 0.37, p < 0.01) |

| Chan et al. 2010 (BC) | C | 48.4 | 15.6 PD | Positive attentional bias α PTG (r = 0.60, p < 0.001) |

| Positive cancer related rumination α PTG (r = 0.51, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Morris et al. 2010 (H) | C | 62.41 | 36 PD | Intrusive rumination α PTG |

| Rumination on benefits α PTG life purpose | ||||

| Rumination α PTG (covariance parameters were all significant for the three rumination types above, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Bozo et al. 2009 (BC) | C | 46.3 | 2–276 PD | Dispositional optimism α PTG (β = 0.25, p < 0.05, R 2= 0.06) |

| Mols et al. 2009 (BC) | C | 62% between 50–69 | Not mentioned | Benefit finding α PTG (β = 0.46, p < 0.001) |

| Karanchi et al. 2007 (BC) | C | 43.0 | 15.4 PT | Problem solving coping α PTG (t(78) = 4.80, p < 0.001) |

| Smith et al. 2008 (CC) | C | 51.0 | 120 PD | Spirituality α PTG (0.271, P < 0.01) |

| Thornthon et al. 2006 (PC ) | L | 61.3 | 12 PT | Positive reframing coping α PTG (p < 0.001) |

| Schroevers et al. 2006 (H) | C | 51.8 | 45 PT | Active positive coping α PTG (Ρ < 0.001) |

| Instrumental support α PTG (β = 0.38, p < 0.01) | ||||

| Positive reframing α PTG (β = 0.21, p < 0.05) | ||||

| Humor α PTG (β = 0.18, p < 0.05) | ||||

| Bellizzi et al. 2006 (BC) | C | 60 | 12-48 PT | Adaptive coping α PTG (for the domains of relationship with others, new possibilities in life, appreciation of life) (β = 0.39, 0.44, 0.43, p < 0.01) |

| Carboon et al. 2005 (H) | L | 43.4 | First assessment: 1.2 PD | Religious coping α PTG (F(2,59) = 6.2, p < 0.004) |

| Second assessment: 6.1 PD | ||||

| Widows et al. 2005 (BMT) | C | 47.6 | 24.1PT | Approach based positive reappraisal, problem solving coping α PTG (p < 0.05) |

| Manne et al. 2004 (BC)a | L | Pt: 49 PR: 51 | 4.5 PD | For patients: cancer rumination α PTG (3.36, p < 0.001) |

| For partners: positive reappraisal α PTG (1.37, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Intrusion α PTG (p = 0.023) | ||||

| Weiss et al. 2004 (BC)a | C | 54.2 | 38.7 PD | Marital support α PTG (r = 0.24, p = 0.046) |

| Sears et al. 2003 (BC) | L | 51.6 | 28.5 PD | Positive reappraisal α PTG (p = 0.01) |

| Positive affectivity α PTG (p = 0.01) | ||||

| Cordova et al. 2001 (BC) | C | 54.7 | 23.6 PT | Cancer rumination α PTG (r = 0.25, p < 0.05) |

C.P cancer population, PC prostate cancer, T type of study design, M.A mean age, Y years, OC oral cancer, H heterogeneous cancer group, BMT bone marrow transplant, PTG posttraumatic growth, C cross-sectional, α significantly associated with, L longitudinal, PT post-treatment, PD post-diagnosis, BC breast cancer, CC cervical Cancer

aStudies that also assessed the spouse/partners

Personality traits and social support

Specific personality traits associated with positive outcomes of coping process (and ultimately PTG) were optimism and hope [7, 8]. These personality traits rendered the individual more receptive for social support and enhanced positive coping methods including positive reappraisal of the disease, religious coping, and problem-based coping [9–17]. Social support from close friends as well as support delivered from the treating team (including doctors and psychologists) was associated with increased PTG [8, 18–21]. Patients living in stable relationships benefitted from good spousal support and therefore revealed a greater tendency to develop positive coping processes, generating thus increased PTG [8, 22, 23].

Benefit finding and meaning making

Benefit finding and meaning making are important processes in helping to involve many active coping measures and thinking processes including rumination [11, 14, 18, 24]. Rumination has been detected to significantly predict the development of PTG [25]. Individuals who are able to successfully find benefit and make meaning are able to develop more PTG either directly as shown be Thombre et al. [26] or by increasing positive cancer rumination [25, 27]. Benefit finding and meaning making increase in patients presenting high levels of hope and optimism which highlights their importance regarding positive coping processes [28].

Positive coping processes

Positive coping has been detected to be consistently linked to effective development of PTG [12, 16, 17, 19, 21, 29, 30]. Studies showed that adaptive coping processes including religious coping [12, 15] and spirituality [31] increased PTG significantly. Positive affectivity also showed significant association with the development of PTG in some studies [12, 14]. Apart from this, literature also emphasizes that using active coping processes including active relational coping [12], problem-focused coping [17, 29], positive attentional bias [27], positive reframing coping [16, 21], as well as adaptive coping [30] consistently showed significant association with PTG, just as increased use of positive reappraisal which was identified as another important factor associated with increased PTG [14, 17, 30]. Further on, other studies highlighted humor [21] and cancer rumination [18, 23, 25] as important predictors of PTG (Table 1).

Discussion

PTG has been widely researched in other oncological fields, especially in the field of breast cancer. OCC patients are an important subgroup of oncological patients as the biological nature of the disease and treatment modalities related to oral cancer results in concomitant loss of function, psychosocial problems as well as loss of quality of life. Such negative effects have been detected to lead to increased PTG in other fields of cancer research. Therefore, it was hypothesized that oral cancer patients might develop PTG, too. Performing an evidence-based review, the authors’ aim was to provide a more structured pathway model for future research especially in the field of OCC. It was found that PTG knowledge especially within the OCC research is lacking. In this review, only studies using the standardized questionnaires for PTG assessment have been included to allow a more standardized comparison. There are many different types of coping processes that have shown some positive outcome regarding PTG but it is the authors’ intention to only focus on “the processes” that have shown significant positive relationship with PTG (Table 1) .

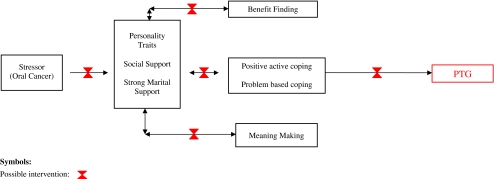

There are a number of factors that ought to be considered in determining the quality of evidence to inform a conceptual framework of interventions for OCC proposed (Fig. 2). Firstly, the evidence compiled is from heterogeneous patient samples and thus coping styles of one particular cancer may not readily be adaptable or useful for OC cancer per se. Secondly, assessment of the “coping processes” varied considerably and in many cases relied on non-standardized measurement instruments (questionnaires), thus differences in measurement approaches may have influenced outcomes observed. Considering such limitations, a hypothetical model for PTG in the OCC discipline is proposed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This model shows the multidimensional concept of PTG being influenced by various coping processes at different stages of cancer disease. Therefore, potential interventions might be applied at different stages of the disease probably providing enhanced coping processes which facilitate the development of PTG

This review identified a few positive coping processes that significantly promoted PTG as well as overriding factors and certain personality traits that lead a person to be more inclined to use this identified coping processes. The overriding factors were identified as benefit finding and meaning making [1, 24] and marital support [23] which will be discussed below. Hope and optimism were the identified personality traits rendered the patient more inclined to practicing positive coping processes [7, 8]. There were a few positive coping processes that have consistently showed significance where positive reframing, religious coping, positive affectivity, active and adaptive coping, rumination, positive attention bias, and problem solving coping. Most of the studies were cross-sectional, thus preventing identification of causal relationship; however, it is our intention here to present these few proven significant processes to allow researchers to develop prospective studies as well as interventional studies that can promote these processes. Our understanding from the literature is that each coping process interrelates with each other. They also developed at specific times along the long process of cancer recovery [32]. It lies in the intention of the authors that the identification of these processes might influence future research to focus toward the points of time when particular processes would develop. This on his part might have an impact on the development and implementation of more timely specific interventional psychological programs. Further on, a theoretical framework for specific interventions to influence the development of PTG in patients at different stages of the disease (Fig. 2) has been forwarded. Thus, psychological programs promoting coping strategies, aiming at specific attributes in particular stages in the cancer tale of woe should be considered in OCC management. In the initial stages, interventions related to social support, couple / family, personality traits, and promoting cancer rumination should be enacted as the here presented results have shown, all of the factors representing patients’ predispositions to positive coping processes mentioned before.

It has long been recognized that “social support” plays an important role in coping with cancer, including OCC patients [20, 22]. In particular, the involvement of spouses/partner and family appears to be important in developing appropriate coping strategies [22, 23]. Evidence in the OCC field has already identified that patients from strong supportive marriages/partnerships are more able to develop benefit finding and meaning making [33]. Therefore, couples or family therapy probably should be implemented to yield the necessary support for both the patients and their spouses at the earliest time possible. Another important facet of social support may come from contact with persons who have experienced a similar adversity. Improved coping response was found in patients being in contact with persons who have experienced a similar adversity [34].

Overriding constructs are “benefit finding” (BF) and “meaning making” (MM). BF is a process in which the patient creates a new positivity to the adverse event based on the benefit the patient identifies. This process makes the individual look at the adverse event as an opportunity to self-improve and at the same time develop PTG to uphold the damaged self-esteem [1, 24]. MM on the other hand is a process which develops after the adverse events in which the individual starts reviewing their current beliefs and world assumptions. This will then allow the individual to derive positive explanations regarding the adverse event and start making sense of the cancer experience thus allowing change in their basic beliefs. MM generates new vision of the self, others and world beliefs which all directly relates to coping [1]. Interestingly, BF and MM have a positive effect on increasing the use of positive coping processes in patients [11]. Thus, any psychological intervention that can increase benefit finding and meaning making earlier on in the cancer process may be able to enhance coping and ultimately bring about PTG in OCC patients.

The next area of focus relates to “positive active coping” which includes religious and spiritual development, problem solving coping initiatives, active cancer rumination, and acceptance coping which all show significant association with PTG [12, 18, 19, 26, 27, 29, 30]. All these positive coping processes are significant contributors to PTG as they require effort to process rebuild the patient’s beliefs and outlook in life [19]. Acceptance, coping strategies, humor, and rumination appear particularly important in the early stages of cancer leading patients to develop a more positive outlook later on in the cancer experience [18, 21, 23, 27, 35]. This implies that interventional therapies might play a role in the development of positive coping strategies in OCC patients with particular relevance in the early stage of cancer.

The proposed hypothetical framework for PTG (Fig. 2) in OCC management is based on this evidence-based review of literature, thus providing a sound theoretical framework. This theoretical framework might also provide a guide for future research in other cancer research fields. It certainly offers various practical strategies and pathways to potentially enhance PTG throughout the trajectory of OCC. Even though some outlined interventions/strategies have already been proven effective in other cancer research fields, there still is a dearth of specific evidence in OCC research.

There is a great need for future studies of psychological interventions to complement cancer management holistically as well as to validate the here proposed theoretical framework with respect to future interventions throughout the trajectory of OCC.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Rama Krsna Rajandram, Email: decruze79@yahoo.com.

Josef Jenewein, Email: Josef.Jenewein@usz.ch.

Colman McGrath, Email: mcgrathc@hku.hk.

Roger Arthur Zwahlen, Phone: +852-28-590265, FAX: +852-25-599014, Email: zwahlen@hku.hk.

References

- 1.Sumalla EC, Ochoa C, Blanco I. Posttraumatic growth in cancer: reality or illusion? Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tedechi RG, Calhoun LG, editors. Trauma and transformation: growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bussel VA, Naus MJ. A longitudinal investigation of coping and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28:61–78. doi: 10.1080/07347330903438958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoellner T, Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology—a critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor SE, Armor DA. Positive illusions and coping with adversity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;64:873–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–249. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho S, Rajandram RK, Chan N, Samman N,McGrath C,Zwahlen RA (2011) The roles of hope and optimism on posttraumatic growth in oral cavity cancer patients. Oral Oncol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bozo O, Gundogdu E, Buyukasik-Colak C. The moderating role of different sources of perceived social support on the dispositional optimism—posttraumatic growth relationship in postoperative breast cancer patients. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(7):1009–1020. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carboon I, Anderson VA, Pollard A, Szer J, Seymour JF. Posttraumatic growth following a cancer diagnosis: do world assumptions contribute? Traumatology. 2005;11:269–283. doi: 10.1177/153476560501100406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karademas EC, Karvelis S, Argyropoulou K. Short communication: stress-related predictors of optimism in breast cancer survivors. Stress Health. 2007;23:161–168. doi: 10.1002/smi.1132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechner SC, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weaver KE, Philips KM. Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:828–840. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lelorain S, Bonnaud-Antignac A, Florin A. Long term posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: prevalence, predictors and relationships with psychological health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(1):14–22. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroevers MJ, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R. The role of social support and self-esteem in the presence and course of depressive symptoms: a comparison of cancer patients and individuals from the general population. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:375–385. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive re-appraisal coping, and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):487–497. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thombre A, Sherman AC, Simonton S. Religious coping and posttraumatic growth among family caregivers of cancer patients in India. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28:173–188. doi: 10.1080/07347330903570537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton AA, Perez MA. Posttraumatic growth in prostate cancer survivors and their partners. Psychooncology. 2006;15:285–296. doi: 10.1002/pon.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widows MR, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M, Fields KK. Predictors of posttraumatic growth following bone marrow transplantation for cancer. Health Psychol. 2005;24:266–273. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordova MJ, Cunningham LL, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychol. 2001;20(3):176–185. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karanci NA, Erkam A. Variables related to stress-related growth among Turkish breast cancer patients. Stress Health. 2007;23:315–322. doi: 10.1002/smi.1154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinsinger DP, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Dahn JR, Lechner S, Schneiderman N. Psychosocial and sociodemographic correlates of benefit finding in men treated for localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:954–961. doi: 10.1002/pon.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroevers MJ, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R. Adjustment to cancer in the 8 years following diagnosis: a longitudinal study comparing cancer survivors with healthy individuals. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:598–610. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, Jenewein J, Buchi S. Posttraumatic growth in cancer patients and partners—effects of role, gender and the dyad on couples’ posttraumatic growth experience. Psychooncology. 2009;19:12–20. doi: 10.1002/pon.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manne S, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Goldstein L, Fox K, Grana G. Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: patient, partner and couple perspectives. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:442–454. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127689.38525.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health. 2009;24(5):583–595. doi: 10.1080/08870440701671362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J. Rumination, post-traumatic growth, and distress: a structural equation modelling with cancer survivors. Psychooncology. DOI: 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thombre A, Sherman AC, Simonton S. Posttraumatic growth among cancer patients in India. J Behav Med. 2010;33(1):15–23. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan MW, Ho SM,Tedeschi RG,Leung CW (2011) The valence of attentional bias and cancer-related rumination in posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Harrington S, McGurk M, Llewellyn CD. Positive consequences of head and neck cancer: key correlates of finding benefit. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26:43–62. doi: 10.1080/07347330802115848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scrignaro M, Barni S, Magrin ME. The combined contribution of social support and coping strategies in predicting post-traumatic growth: a longtitudinal study on cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/pon.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellizzi KM, Blank TO. Predicting posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):47–56. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith BW, Dalen J, Bernard JF, Baumgartner KB. Posttraumatic growth in non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women with cervical cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26(4):91–109. doi: 10.1080/07347330802359768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gail L, Towsley SLB, Watkins JF. "Learning to live with it": coping with the transition to cancer survivorship in older adults. J Aging Stud. 2007;2:193–106. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenewein J, Zwahlen RA, Zwahlen D, Drabe N, Moergeli HB. Quality of life and dyadic adjustment in oral cancer patients and their female partners. Europe J Canc Care. 2008;17:127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss T. Correlates of posttraumatic growth in married breast cancer survivors. J Soc Clin Psyc. 2004;23:733–746. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.733.50750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, Noriega V, Scheier MF, Robinson DS, Ketcham AS, Moffat FL, Jr, Clark KC. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:375–390. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]