Abstract

Purpose

Fatigue is a symptom with a relevant impact on the daily lives of cancer patients and is gaining importance as an outcome measure. The Perform Questionnaire (PQ) is a new scale originally developed among Spanish-speaking patients for the assessment of perception and beliefs about fatigue in cancer patients.

Methods

An observational longitudinal multicenter study was carried out on cancer patients with fatigue. Fatigue-specific measures (FACT-F), generic health-related quality-of-life measures (NHP), and PQ were gathered at baseline and 3 months later. Feasibility, reliability (internal consistency and test–retest), validity, sensitivity to change, and minimally important differences were analysed.

Results

Four hundred thirty-seven patients were included in the study: 60.5% were women, the mean age was 59.1 years, the mean time from diagnosis was 2.2 years, 33.6% of patients had breast cancer, and 29.1% had anaemia (haemoglobin (Hb) <11 g/dL). Low levels of missing items and ceiling/floor effects (<10%) were found. The overall Cronbach’s alpha and intraclass correlation coefficient were 0.94 and 0.83, respectively. The PQ score was associated with fatigue intensity, the need for a caregiver, and the Hb level. Its association was stronger with the FACT-F than with non-specific health measures (NHP). The PQ showed good sensitivity to change for improved and worsening health status. A minimally important difference of 3.5 was estimated in patients whose Hb level had improved by at least 1 g/dL.

Conclusions

The PQ measured the attitudes and beliefs about fatigue among cancer patients in clinical practice and showed good psychometric properties among Spanish-speaking patients.

Keywords: Cancer, Oncology, Fatigue, Validity, Reliability, Questionnaire

Background

According to studies published recently within the cancer epidemiology and health research outcomes areas, fatigue is one of the most frequent symptoms with a major impact on oncology patients [1–3]. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF), which has been defined as a “distressing persistent subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness” [4], is a very prevalent symptom that can affect more than three quarters of oncology patients [5–8]. Fatigue is undertreated [5, 6], prevents a “normal” life [9], and could have a greater impact on the quality of life than pain or depression, which are symptoms also observed frequently in cancer patients [5]. Excellent reviews addressing fatigue in cancer patients and its associated problems have been published recently [10–12].

The need to deepen our understanding of the impact of fatigue interventions on outcomes such as quality of life [13, 14] has been recognised recently, for which adequate and duly validated and developed instruments are required. This underscores yet again the importance of integrating clinical and outcomes research in daily clinical practice [15]. A new instrument to measure patient perceptions of fatigue in cancer and its treatment has been developed: the Perform Questionnaire [16], originally developed for Spanish-speaking patients and created with the intention of being a feasible and valid tool for evaluating, from a patient perspective, the perceptions associated with fatigue within usual clinical practice. Initially, the instrument development procedure focused on item generation and item reduction, as well as on exploring the structural validity and internal consistency of the instrument [16], while assuring certain formal characteristics in terms of length, scoring system, etc., which are characteristics that can often jeopardise the feasibility of the tool in usual clinical practice, as demonstrated in other health areas [17].

Subsequently, the psychometric properties of the new tool were assessed, an indispensable requirement for fulfilling the purpose of using the new tool in the target population. The aim of this paper was to report the findings of the validation study of the Perform Questionnaire.

Patients and methods

To assess the reliability of the new PQ, as well as its validity and sensitivity to change, we performed a prospective and observational study between November 2005 and September 2006 in the oncology and palliative care departments of 50 Spanish public hospitals. Each centre consecutively included patients with the following characteristics: (a) ambulatory and over 18 years of age; (b) with a diagnosis of cancer (any site and period of disease duration, as long as they were capable of completing the study questionnaires); (c) with a self-rated fatigue intensity ≥30 mm on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) at the time of the study visit [4]; and (d) with a life expectancy of over 6 months. All patients provided informed consent to participate in the study, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic i Provincial in Barcelona and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient assessments were performed at the time of inclusion in the study and 3 months later to assess test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change. We collected data regarding sociodemographic factors (i.e. sex, age, level of education, and level of family care required) and clinical characteristics (including cancer location, extent of the disease, haemoglobin level, cancer treatment, time since diagnosis, Karnofsky index on inclusion, and intensity of fatigue measured on a 100 mm horizontal VAS).

The PQ [16] is a new questionnaire developed by clinicians that uses patient perspectives for assessing the perception of fatigue in cancer. It consists of 12 items with responses on a five-point ordinal scale. The 12 items are distributed in three dimensions: “Physical Limitations”, “Activities of Daily Living”, and “Beliefs and Attitudes”. An overall score and three-dimension scores are obtained, with low scores indicating worse patient perception of fatigue.

The new questionnaire was self-administered together with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Fatigue (FACT-F) [18, 19]. The FACT-F consists of 13 items related to fatigue with responses to the individual items on a five-point ordinal scale and overall scores range from 13 (no impairment) to 65 (greatest impairment). The new questionnaire was also self-administered together with the short version of the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) [20, 21]. The NHP-22 questionnaire is a generic health-related quality-of-life measure that has two summary scores: physical and psychological dimensions [21]. Each dimension score ranges from 0 (minimum impact in Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)) to 100 (maximum impact in HRQOL).

Patients were also asked to rate the new questionnaire’s ease of use on a scale ranging from “Very difficult to complete” to “Very easy to complete”, and the time taken to complete the questionnaire was recorded.

A “health status transition” item was self-administered at the second visit, to assess changes in health status perception from the first visit. Patients provided answers based on a Likert-type ordinal scale with 13 response options ranging from “have greatly improved” to “have greatly worsened”. The results were used in the analysis of sensitivity to change.

Statistical analyses

The questionnaire’s feasibility was assessed by examining responses to the ease of use question and the time taken to complete the questionnaire. The lost information was also assessed by calculating the completion rate (the percentage of responders with no missing data in any of the 12 items) and the range of missing answers (the maximum number of missing responses per item).

The distribution of the overall and dimension scores was analysed by calculating mean scores, standard deviations (SDs), observed score ranges, and floor and ceiling effects (the proportion of patients with the worst and the best possible scores, respectively) for the overall score and for each dimension of the PQ.

The instrument’s internal consistency was assessed by estimating Cronbach’s alpha (CA) [22] coefficients for individual dimensions and the overall score at the baseline. We hoped to obtain a CA over 0.70, as recommended in the literature [23, 24]. The 3-month test–retest reliability was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between visits among patients who did not report any significant change (<5 mm) in VAS fatigue intensity between study visits.

The known groups’ validity was tested by determining whether the instrument was able to discriminate between patient groups likely to differ in fatigue perception according to variables such as intensity of fatigue, anaemia prevalence, level of Hb, and need for a caregiver.

The convergent validity was tested by estimating Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the PQ and scores of the FACT-F, the NHP, and the Karnofsky index [25]. We expected correlations to be higher between the PQ and the FACT-F, as both are disease-specific instruments, than between the PQ and other health measures such as the NHP and the Karnofsky index.

The sensitivity to change was assessed by calculating the effect size (ES; i.e. the standardised mean score change) and standardised response mean (SRM) in the subgroup of patients who reported at least a “small improvement” on the health status transition item as well as in the subgroup of patients who reported at least a “small deterioration” on the aforementioned item. ES values of approximately 0.2 were considered as representing a small change, while values of approximately 0.5 indicated a moderate change, and values of approximately 0.8 or higher represented a large change in the attribute of interest [26]. The SRM was calculated by dividing the mean change in score by the SD of the change scores between the two study visits [24].

To improve the interpretation of the observed numerical differences in the PQ, the minimally important difference (MID) that would imply a clinically meaningful outcome was determined according to the method described in previous studies [27]. An Hb increase of 1 g/dL was considered the minimally important clinical change necessary to evaluate fatigue results. “Improved” patients were defined as those who experienced an increase in Hb ≥1 g/dL. “Stable” patients had a change in Hb < 1 g/dL to a lower limit of −1 g/dL. The difference in the mean PQ change score between the improved and stable groups was considered the MID of the measure.

Statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS software [28].

Results

The study population consisted of 437 patients, whose characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the study population was 59.1 years (SD, 11.8), and 60.5% of patients were female. The most prevalent type of cancer was breast cancer (33.6%), followed by lung (14.9%) and colon (11.4%) cancer. Time from diagnosis was 2.2 years, with a current Karnofsky mean score of 81.3 (SD, 11.6). Fifty-four and seven percent of patients had metastasis, and almost a third of the patients presented with anaemia at inclusion. Only 10% of the sample was enrolled in follow-up, while the remaining 90% was undergoing cancer treatment. The most prevalent treatment in the study population was chemotherapy (as a single therapy or as combined therapy), followed by radiotherapy, which was used in only 14% of the sample.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the validation study sample (N = 437)

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Women | 264 (60.5) |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 59.1 (11.8) |

| Educational level, N (%) | |

| No formal education | 92 (22) |

| Primary education | 181 (43.8) |

| Secondary education | 81 (19.4) |

| University or similar | 62 (14.8) |

| Carer status, N (%) | |

| Patient does not need care from other person | 292 (68.5) |

| Patient needs and receives care from the family, the caregiver, or both | 134 (31.5) |

| Time from diagnosis, mean years (SD) | 2.21 (3.9) |

| Karnofsky score on inclusion, mean (SD) [min, max] | 81.3 (11.6) [50, 100] |

| Cancer location, N (%) | |

| Breast | 147 (33.6) |

| Lung | 65 (14.9) |

| Colon | 50 (11.4) |

| Rectum | 34 (7.8) |

| Ovary | 27 (6.2) |

| Prostate | 22 (5) |

| Othera | 96 (22) |

| Cancer extension, N (%) | |

| Local | 90 (20.8) |

| Loco regional | 106 (24.5) |

| Metastasis | 237 (54.7) |

| Hb <11 g/dL, N (%) | 127 (29.1) |

| Hb (g/dL), mean (SD) [min, max] | 12 (1.7) [6.9, 18] |

| Treatment status, N (%) | |

| Follow-up surveillance | 43 (9.8) |

| Active treatment | 394 (90.2) |

| Type of cancer treatmentb, N (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 368 (84.2) |

| Radiotherapy | 60 (13.7) |

| Hormone therapy | 48 (11) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 41 (9.4) |

| Interferon | 6 (1.4) |

| VAS fatigue score on inclusion, mm; mean (SD) [min, max]**, c | 54.3 (15.1) [30, 95] |

| VAS fatigue level on inclusion, N (%) | |

| Moderate (30–60 mm) | 227 (65.6) |

| Severe (>60 mm) | 119 (34.4) |

| Following a fatigue treatment, N (%) | 152 (34.8) |

| FACT-Fd, mean (SD) | 35.9 (10.5) |

| NHP-22e, mean (SD) | |

| Physical summary score | 33.4 (24.1) |

| Psychological summary score | 34.2 (26.8) |

SD standard deviation, min minimum, max maximum, Hb haemoglobin, VAS visual analogue scale, NHP Nottingham Health Profile, FACT-F Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Fatigue

aIncludes bladder (N = 18), pancreas (N = 16), lymphoma (N = 12), head and neck (N = 11), stomach (N = 10), and several other cancers with N < 5

bIncludes indiscriminately indications in single therapy and combined therapy

cFatigue was measured on a 100-mm, horizontal VAS

dGlobal score ranges from 13 (no impairment) to 65 (greatest impairment)

eDimension scores range from 0 (minimum impact in HRQOL) to 100 (maximum impact in HRQOL)

As Table 2 shows, more than 80% of the patients considered that the PQ was very easy or easy to answer, and the mean time required for its administration was under 9 min. Over 80% of the study patients answered 100% of the questionnaire items. In general, all of the items showed low levels of lost answers (<4%), with the exception of question 8 (“I’ve felt bad about feeling tired at work”), which was left unanswered by 16% of the patients. Floor/ceiling effects were negligible (<2%) for the overall score and low (<9%) for all dimensions. The highest floor/ceiling effect (8.6%) was detected in the “Physical limitations” dimension. The Cronbach’s alpha for the overall score was 0.94, and it was at least 0.80 for each dimension. The ICC values found in the subgroup of patients considered “stable” were above 0.75 for the dimensions and 0.83 for the overall score.

Table 2.

Feasibility, score distributions, and reliability of the Perform Questionnaire (N = 437)

| Physical limitations | Activities of daily living | Beliefs and attitudes | Global scorea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items (N) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Mean | 11.5 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 34.8 |

| SD | 4.7 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 12 |

| Time taken for administration, mean (SD) | – | – | – | 8.8 (8.9) |

| Easy or very easy to answer the questionnaire, N (%) | – | – | – | 343 (81.1) |

| Completion rateb, N (%) | 419 (95.88) | 417 (95.42) | 358 (81.92) | 351 (80.32) |

| Range of missing answers, N (%) | 2.5% (item 1)–3.7% (item 2) | 2.3% (item 6)–16.9% (item 8) | 2.3% (item 12)–3.7% (item 9) | 2.3% (items 6,12)–16.9% (item 8) |

| Theoretical rangea | 4–20 | 4–20 | 4–20 | 12–60 |

| Observed rangea | 4–20 | 4–20 | 4–20 | 12–60 |

| Floorc (%) | 8.6 | 2.1 | 6.9 | 1.7 |

| Ceilingd (%) | 4.3 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| Internal consistency, CA | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.94 |

| Test–retest reliability among stable patients (N = 64)e | ||||

| Mean score (SD) at visit 1 | 11.9 (4.6) | 11.7 (3.8) | 11.7 (4.4) | 35.5 (12.1) |

| Mean score (SD) at visit 2 | 11.5 (4.3) | 11.5 (3.5) | 11.0 (44.4) | 34.3 (11.5) |

| ICC | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

CA Cronbach’s alpha, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient, SD standard deviation

aLow scores indicate worse patient perception of CRF

bPercentage of respondents with no missing data in any of the 12 items

cPercentage of patients with the worst possible score

dPercentage of patients with the best possible score

eStability defined as a change <5 mm in the VAS fatigue between study visits

Patients with the highest (severe) levels of fatigue intensity obtained worse Perform overall and dimension scores than patients with moderate fatigue intensity (P < 0.0001; Table 3). Patients who needed a caregiver, anaemic patients, and patients with lower levels of Hb obtained worse Perform overall (P = 0.0001 to 0.0006) and dimensions scores (P = 0.0001 to 0.0036) than patients who did not need a caregiver, were non-anaemic, and had higher levels of Hb. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the Perform overall score and the Hb level at baseline was 0.18 and ranged between 0.14 (“Physical limitations”) and 0.20 (“Activities of daily living”).

Table 3.

Mean (SD) scores for perform questionnaire overall and dimensions scores (low scores indicate worse patient perception of cancer-related fatigue), according to clinical baseline characteristics (N = 437)

| Physical limitations | Activities of daily living | Beliefs and attitudes | Global score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS fatigue level on inclusion, mean (SD) | ||||

| Moderate (30–60 mm) | 12.4 (4.6) | 12.6 (3.6) | 12.3 (4.3) | 37.7 (11.3) |

| Severe (>60 mm) | 9.3 (4.1) | 9.5 (3.6) | 8.9 (4) | 28 (10.6) |

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Caregiver | ||||

| Patient needs caregiver | 9.6 (4.4) | 10.5 (3.9) | 9.2 (4.1) | 29.6 (11.6) |

| Patient does not need caregiver | 12.3 (4.6) | 12.2 (3.8) | 12.2 (4.3) | 37 (11.7) |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Anaemia prevalence | ||||

| Anaemic patients (Hb < 11 g/dL) | 10.5 (4.7) | 10.6 (3.7) | 10.1 (4.5) | 31.5 (11.6) |

| Non-anaemic patients (Hb > 11 g/dL) | 12 (4.6) | 12.2 (3.8) | 11.8 (4.3) | 36.3 (11.8) |

| P value | 0.0036 | < 0.0001 | 0.0009 | 0.0006 |

| Levels of Hb (g/dL) | ||||

| <9 g/dL | 8.7 (3.6) | 8.8 (4.1) | 11 (5.5) | 29.4 (12.9) |

| 9–10 g/dL | 10.8 (4.7) | 10.8 (3.6) | 9.3 (3.9) | 31.2 (11.1) |

| 10–11 g/dL | 10.9 (4.8) | 11.0 (3.6) | 10.5 (4.4) | 32.8 (11.7) |

| 11–12 g/dL | 11.5 (4.8) | 11.7 (4) | 11.1 (4.7) | 34.4 (12.4) |

| >12 g/dL | 12.1 (4.6) | 12.4 (3.7) | 12.1 (4.2) | 36.9 (11.5) |

| P value | 0.0010 | <0.0001 | 0.0015 | 0.0006 |

| Pearson’s correlation coefficient | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

VAS visual analogue scale, SD standard deviation, Hb haemoglobin

We used a linear regression model to assess the multivariate association between the Perform overall score and several clinical characteristics (Table 4). Significant results were obtained using the model for sociodemographic variables (educational level); however, they were predominant for clinical characteristics, such as the need for a caregiver, cancer location, fatigue intensity level, Karnofsky score, the presence or absence of cancer treatment, the presence or absence of palliative treatment, and the time from diagnosis. These clinical characteristics were independently associated with the Perform overall score (P = 0.0001 to 0.03) and explained 31% of the variance.

Table 4.

Variables associated with the overall scores of the Perform Questionnaire (linear regression model) (N = 298)

| Variable | Coefficient β | P |

|---|---|---|

| Need for caregiver | −4.37 | 0.0003 |

| Educational level | 1.33 | 0.0303 |

| Cancer location | 0.26 | 0.0278 |

| Fatigue intensity level | −0.30 | <0.0001 |

| Karnofsky | 0.13 | 0.0113 |

| Patient in treatment or in follow-up | 5.04 | 0.0146 |

| In palliative treatment or not | 2.71 | 0.0293 |

| Time from diagnosis | 0.35 | 0.0054 |

Model significance, P < 0.0001; R 2 = 0.3065

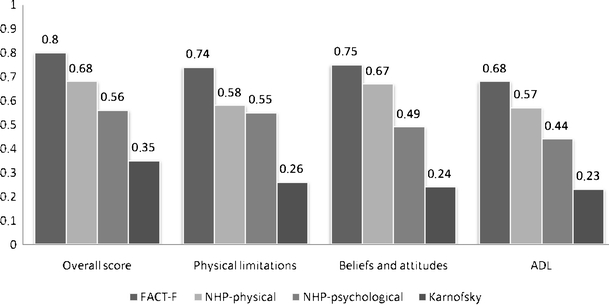

The comparison of PQ scores with the other health measures (i.e. FACT-F, NHP, and Karnofsky index) revealed stronger correlations between Perform scores and the FACT-F (overall = 0.80; dimensions = 0.68–0.75) than between Perform scores and the NHP dimensions (overall Perform with Physical NHP = 0.68; overall Perform with Psychological NHP = 0.56; Perform dimensions with Physical NHP = 0.57–0.67; Perform dimensions with Psychological NHP = 0.44–0.55) or between Perform scores and Karnofsky index (overall = 0.35; dimensions = 0.23–0.26; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pearson Correlation between the Perform Questionnaire and the FACT-F, NHP-22 and Karnofsky scores (N=437)

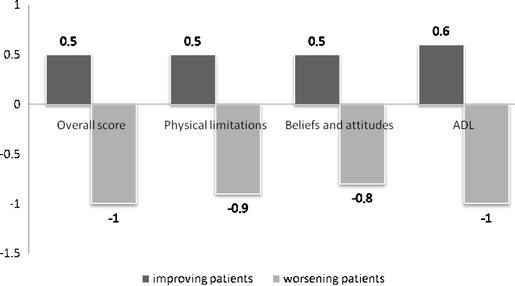

The sensitivity to change (Table 5) was assessed among the subgroup of 208 patients who self-reported an improvement in their health status since the time of their first visit 3 months earlier, as well as among the subgroup of 84 patients who self-reported deterioration in their health status since their first visit. In general, the ES and the SRM values were higher for patients who worsened than for patients who improved. For instance, the ES for the Perform overall score among patients who improved indicated a moderate health improvement (0.57). However, the ES for the Perform overall score among patients who worsened suggested great health deterioration (−1). Perform dimension scores also behaved according to this pattern (ES for improved patients = 0.5–0.6; ES for worsened patients = 0.73–0.83; Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Sensitivity to change and clinical significance of the improvement of the Perform Questionnaire Score

| Physical limitations | Activities of daily living | Beliefs and attitudes | Global score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity to improvementa (N = 208) | ||||

| Mean score (SD), visit 1 | 11.7 (4.6) | 11.8 (3.7) | 11.5 (4.4) | 35.3 (11.7) |

| 95% CI | 11.1–12.4 | 11.3–12.3 | 10.8–12.1 | 33.5–37.1 |

| Mean score (SD), visit 2 | 13.9 (4.1) | 13.9 (3.4) | 13.6 (4.1) | 41.4 (10.7) |

| 95% CI | 13.3–14.5 | 13.4–14.3 | 13.0–14.2 | 39.8–43.0 |

| Effect size | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| SRM | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.57 |

| Sensitivity to deteriorationb (N = 84) | ||||

| Mean score (SD), visit 1 | 11.6 (4.6) | 12.2 (3.9) | 11.4 (4.4) | 35.6 (11.7) |

| 95% CI | 10.6–12.6 | 11.3–13.0 | 10.4–12.5 | 32.7–38.4 |

| Mean score (SD), visit 2 | 8 (3.7) | 8.6 (3.3) | 8.1 (3.6) | 25.1 (10) |

| 95% CI | 7.1–8.8 | 7.9–9.4 | 7.3–9.0 | 22.7–27.6 |

| Effect size | −0.9 | −1 | −0.8 | −1 |

| SRM | −0.73 | −0.83 | −0.73 | −0.76 |

| Clinical significance (N = 288) | ||||

| Mean change (SD) among stable patientsc | 0.22 (4.97) | 0.40 (4.61) | 0.10 (4.45) | 0.03 (12.69) |

| Mean change (SD) among improved patientsd | 1.43 (4.74) | 1.15 (4.23) | 1.30 (4.31) | 3.72 (10.22) |

| Minimally important difference (MID)e | 1.21 | 0.75 | 1.2 | 3.69 |

Overall score ranges from 12 to 60, with low scores indicating worse patient perception of cancer-related fatigue. Dimension scores range from 4 to 20, with low scores indicating worse patient perception of cancer-related fatigue

SD standard deviation, SRM standardised response mean, CI confidence interval

aAmong those patients who reported an improvement in the “health status transition item”

bAmong those patients who reported a deterioration in the “health status transition item”

cPatients who experienced a change in Hb < 1 g/dL to a lower limit of −1 g/dL

dPatients who experienced an increase in Hb ≥ 1 g/dL

eThe difference between the mean change of stable patients and the mean change of those who improved

Fig. 2.

Effect sizes obtained for the Perform Questionnaire among patients who reported on improvement or deterioration, respectively, in the "health status transition item"

Eighty-seven patients experienced an increase in Hb ≥1 g/dL, while 201 patients remained “stable” at 3 months (Table 5). The mean change in Perform overall score for “Hb-stable” patients was 0.03, and the mean Perform overall score change for “Hb-improved” patients was 3.72. The MID for the Perform overall score, which implied a clinically meaningful outcome, was a score change of 3.69 (i.e. the difference between 0.03 and 3.72).

Discussion

The PQ, like any questionnaire or health scale meant for use in clinical research or clinical practice, must be guaranteed by rigorous validation and development procedures, as described in the literature [23, 24, 29]. In this sense, the PQ was developed, modified, and validated using standardised test construction methods consistent with US Food and Drug Administration guidelines [29].

The PQ is a tool originally developed using Spanish-speaking patients from Spain; therefore, its application to Spanish speakers within a Hispanic culture would be relatively easy after correction for cultural adaptation according to the agreed-upon guidelines for this purpose [30]. Moreover, the PQ was created with the intention of being a feasible, valid, and useful tool for assessing, from a patient perspective, the perceptions associated with fatigue in cancer within usual clinical practice. That is to say, this measure was developed with the belief that it could be converted into a real tool to be used by physicians and health professionals who normally manage and assist oncology patients. Therefore, its development process has been lengthy and meticulous, and the validation performed and reported in this article tested exhaustively some of the most relevant psychometric properties and characteristics for the use of health measures in clinical practice [30].

The PQ was well received by the study population. Its administration required less than 9 min, and >80% of the subjects classified it as “very easy” or “easy” to answer. Importantly, there was a low level of lost answers for all items, with the exception of the item “I’ve felt bad about feeling tired at work,” which was associated with a rate of lost answers of 16%. Taking into account that oncology patients are often not fit enough to work and that the format of the administered questionnaire did not include item responses like “not applicable” or “does not apply”, the aforementioned 16% probably included cases that understood the item in question but were unable to answer, as none of the five response options was adequate. In further studies regarding the PQ, this point will have to be corrected, and the option “not applicable” or “does not apply” will be added. Nevertheless, the response rate for the questionnaire (patients with all 12 items answered) was over 80%. These results are especially satisfactory within a sample of oncology patients whose common and main characteristic are precisely those of suffering from fatigue while responding to the measure.

Some patients obtained the worst or the best possible overall scores and dimension scores, which suggests that the questionnaire satisfactorily covers the perceptions of fatigue as presented by the target population under study [31]. The analysis of the internal consistency yielded satisfactory results. The Cronbach’s alpha value obtained for the questionnaire’s summary score (i.e. with all 12 items) was well over 0.70 (Table 2), which is usually considered a standard value [24] and verges on what some authors [23] consider a value that would permit the administration and individual interpretation of the questionnaire without additional samples or patient populations. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the three dimensions of the PQ were positive and comfortably above standard values. The test–retest reliability, another measure of reliability, was analysed using patients who did not report any significant change (<5 mm) in the VAS fatigue intensity between study visits. Regarding the “stable” subgroup, the questionnaire showed a reproducibility of satisfactory scores (ICC >0.70) and was within accepted standards [24] both for summary scores and for dimension scores [32–34].

The analysis of the validity of the questionnaire was concentrated on assessing the behaviour of the PQ’s scores in certain patient profiles that, a priori, were appreciably different with respect to the perception of fatigue. In this sense, and consistent with the expected results, the PQ scores, i.e. the perception of fatigue, were worse in patients with greater fatigue intensity, patients who needed and had a caregiver involved in their daily lives, and patients suffering from anaemia or with lower Hb levels. These studies are coherent with the results reflecting a low or moderate association with the scores of others fatigue scales (mainly through the use of the FACT-F or FACT-An questionnaires; similar data have not been found in other questionnaires) and Hb levels [18, 34–37]. However, no previous studies used a standardised scale for the assessment of fatigue associated with the need for a caregiver involved in the daily lives of cancer patients, which is further proof of the validity of the PQ. In addition, the multivariate analysis showed that two of the above-mentioned variables (need for a caregiver and fatigue intensity) were independent variables particularly associated with the overall PQ scores.

The behaviour analysis of the PQ scores was also focused on the assessment of convergent and divergent validity with respect to specific health questionnaires for fatigue, such as the FACT-F (convergent validity), and with respect to non-specific questionnaires for fatigue, such as the NHP and Karnofsky index (divergent validity). The relationship between the Perform and FACT-F questionnaires was, as expected, high to very high, as these are tools whose content is well associated. However, the relationship between the PQ and the NHP was more moderate, and the correlation between the PQ and the Karnofsky index was low. This pattern of correlations, which was consistent with what was expected (the greater the similarity in assessed concepts, the greater the relationship and vice versa) was reproduced for both the overall scores of the questionnaire and for the dimension scores, and was consistent with associations between performance status and diverse fatigue questionnaires reported previously [18, 35, 38–40].

Sensitivity to change in the Perform scores was assessed. This property was analysed using two subgroups of patients: those who considered that their health status with respect to fatigue had “improved” since the previous visit and those who considered that it had “worsened”. In both groups, the questionnaire scores underwent an expectable, coherent, and consistent change for better or worse, respectively. The change was from slight to moderate in patients who showed a certain improvement according to the interpretation of Cohen’s ES [26]. In patients who reported a worsening in their health status, the ES was between moderate and great, which indicates that the change had been greater (worse) among those who had reported worsening than among those who had reported an improvement. Sensitivity to change, a metric property that indicates the extent of the ability of the questionnaire to detect change (from better to worse) within the health concept assessed by the patients, is rarely tested when validating these kinds of questionnaires [35, 41], although knowledge of the sensitivity of a measure for fatigue in cancer would allow suitable follow-up of the health status of oncology patients. In this case, we demonstrated the sensitivity of the PQ regarding improvement and worsening of fatigue, which could be of great use in clinical practice and for research purposes.

Finally, and following the recommendations of the most recent guidelines [29], it was desirable to estimate the minimum change (improvement) in the overall score of the PQ required to identify a clinical relevant improvement. Using an adaptation of the method used previously [27], we estimated in 3.5 points the aforementioned minimum change in the overall PQ score, and this value would represent an improvement of 1 g/dL in patients’ Hb levels.

In conclusion, the PQ is a questionnaire designed to assess the attitudes and beliefs about fatigue in cancer and its treatment in clinical practice that is feasible, reliable, valid, and sensitive to improvement or deterioration. Its characteristics, content, and demonstrated psychometric properties are likely to render it highly applicable for use in clinical practice in different Spanish-speaking target populations and cultures.

Acknowledgments

Source of financial support

This study was funded by Amgem S.A. José Antonio Gasquet is an employee of Amgen S.A.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Borneman T, Piper BF, Sun VC, et al. Implementing the Fatigue Guidelines at one NCCN member institution: process and outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:1092–1101. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Wagner LJ. The effects of cancer-related pain and fatigue on functioning of older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:421–433. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000300168.88089.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, et al. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2008) Clinical practice guideline in oncology. Cancer-related fatigue. Version 4. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/fatigue.pdf. Accessed Dec 2, 2008

- 5.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: results of a tripart assessment survey. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry DH, Viswanathan HN, Wade SM, et al. The patient’s experience of fatigue: cross-sectional study of cancer. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12:4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strömgren AS, Goldschmidt D, Groenvold M, et al. Self-assessment in cancer patients referred to palliative care: a study of feasibility and symptom epidemiology. Cancer. 2007;94:512–520. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5:353–360. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Vadaparampil ST, Small BJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological and activity-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Health Psychol. 2007;26:660–667. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luctkar-Flude MF, Groll DL, Tranmer JE, Woodend K. Fatigue and physical activity in older adults with cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:E35–E45. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000290815.99323.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sood A, Barton DL, Bauer BA, Loprinzi CL. A critical review of complementary therapies for cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:8–13. doi: 10.1177/1534735406298143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahlberg K, Ekman T, Gaston-Johansson F, Mock V. Assessment and management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Lancet. 2003;362:640–650. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown P, Clark MM, Atherton P, et al. Will improvement in quality of life (QOL) impact fatigue in patients receiving radiation therapy for advanced cancer? Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:52–58. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000190459.14841.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apolone G. Clinical and outcome research in oncology. The need for integration. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baró E, Carulla J, Cassinello J, et al. Development of a new questionnaire to assess patient perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: item generation and item reduction. Value Health. 2009;12:130–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe F, Pincus T, Thompson AK, Doyle J. The assessment of rheumatoid arthritis and the acceptability of self-report questionnaires in clinical practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:59–63. doi: 10.1002/art.10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella D. Factors influencing quality of life in cancer patients: anemia and fatigue. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:S43–S46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cella D, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto L, Alonso J, Lamarca R, Wright BD. Rasch measurement for reducing the items of the Nottingham Health Profile. J Outcome Meas. 1998;2:285–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prieto L, Alonso J, Lamarca R (2003) Classical test theory versus Rasch analysis for quality of life questionnaire reduction. Health Qual Life Outcomes[serial online]; 1:27. http://www.hqlo.com/content/1/1/27. Accessed Dec 2, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunnally J, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949. p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick DL, Gagnon DD, Zagari MJ, Epoetin Alfa Study Group et al. Assessing the clinical significance of health-related quality of life (HrQOL) improvements in anaemic cancer patients receiving epoetin alfa. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:335–345. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute. October. http://www.sas.com/industry/pharma/

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (2006) Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measure: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes [serial online]; 4:79. http://www.hqlo.com/content/4/1/79. Accessed Dec 2, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHorney CA, Tarlov AR. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res. 1995;4:293–307. doi: 10.1007/BF01593882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meek PM, Nail LM, Barsevick A, et al. Psychometric testing of fatigue instruments for use with cancer patients. Nurs Res. 2000;49:181–190. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cella D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) scale: a new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:S13–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella D, Eton DT, Lai JS, et al. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:547–561. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palumbo A, Petrucci MT, Lauta VM, et al. Italian Multiple Myeloma Study Group. Correlation between fatigue and hemoglobin level in multiple myeloma patients: results of a cross-sectional study. Haematologica. 2005;90:858–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holzner B, Kemmler G, Greil R, et al. The impact of hemoglobin levels on fatigue and quality of life in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:965–973. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okuyama T, Akechi T, Kugaya A, et al. Development and validation of the cancer fatigue scale: a brief three-dimensional self-rating scale for assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:5–14. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okuyama T, Tanaka K, Akechi T, et al. Fatigue in ambulatory patients with advanced lung cancer prevalence, correlated factors, and screening. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:554–564. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein KD, Martin SC, Hann DM, et al. A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:143–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gentile S, Delarozière JC, Favre F, et al. Validation of the French ‘multidimensional fatigue inventory’ (MFI 20) Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2003;12:58–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]