Abstract

We report the establishment of a library of micromolded elastomeric micropost arrays to modulate substrate rigidity independently of effects on adhesive and other material surface properties. We demonstrate that micropost rigidity impacts cell morphology, focal adhesions, cytoskeletal contractility, and stem cell differentiation. Furthermore, early changes in cytoskeletal contractility predicted later stem cell fate decisions at the single cell level.

Cell function is regulated primarily by extracellular stimuli, including soluble and adhesive factors that bind to cell surface receptors. Recent evidence suggests that mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM), particularly rigidity, can also mediate cell signaling, proliferation, differentiation, and migration1,2. Culturing cells on hydrogels derived from natural ECM proteins at different densities has dramatic effects on cell adhesion, morphology, and function3. However, changing densities of the gels impacts not only mechanical rigidity, but also the amount of ligand, leaving uncertainty as to the relevant contribution of these two matrix properties on the observed cellular response. Synthetic ECM analogs such as polyacrylamide or polyethylene glycol gels, which vary rigidity by modulating the amount of cross-linker, has revealed that substrate rigidity alone can modulate many cellular functions, including stem cell differentiation4–6. However, altered cross-linker amount impacts not only bulk mechanics, but also molecular-scale material properties including porosity, surface chemistry, backbone flexibility, and binding properties of immobilized adhesive ligands7,8. Consequently, whether cells transduce substrate rigidity at the microscopic scale (eg sensing the rigidity between adhesion sites) or the nanoscopic scale (eg sensing local alterations in receptor-ligand binding characteristics) remains an open question7,8. While hydrogels will continue to play a major role in characterizing and controlling cell-material interactions, alternative approaches are necessary to further elucidate the basis by which cells sense changes in substrate rigidity.

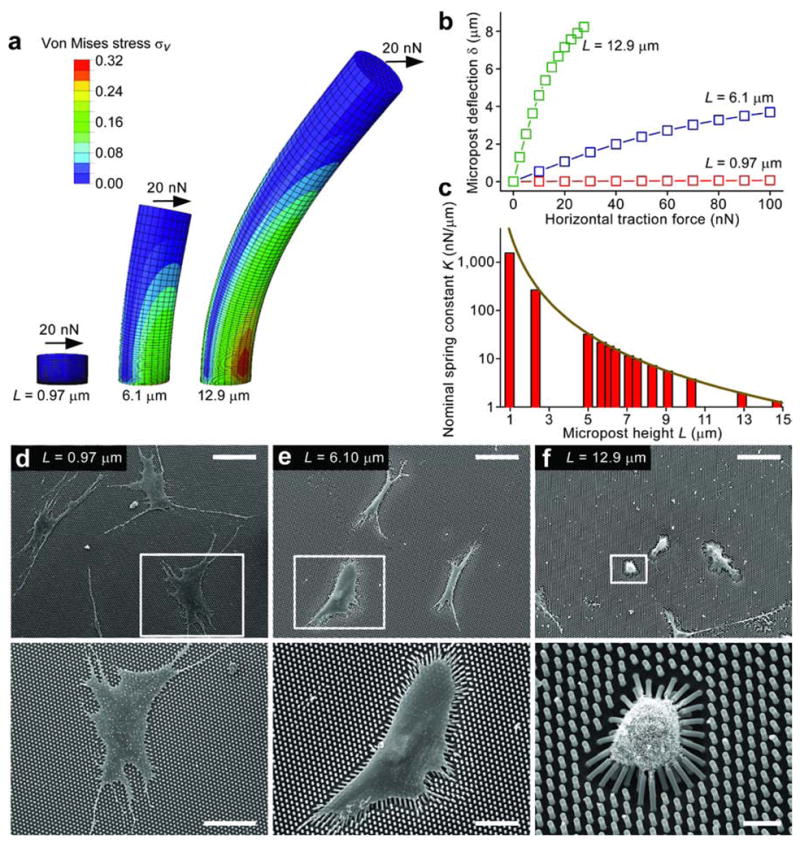

Here we report that micromolded elastomeric micropost arrays9,10 can decouple substrate rigidity from adhesive and surface properties (Fig. 1). Our strategy involved a library of replica-molded arrays of hexagonally spaced poly-(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) microposts from microfabricated silicon masters, which presented the same surface geometry but different post heights to control substrate rigidity (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Online Method). Post height determines the degree to which a post bends in response to a horizontal traction force. We characterized micropost rigidity by computing the nominal spring constant, K, using the finite element method (Fig. 1a–c). The library of micropost arrays spanned a more than 1,000-fold range of rigidity from 1.31 nN/μm up to 1,556 nN/μm. This micropost array library is available to laboratories without the need for reproducing the original silicon templates (www.seas.upenn.edu/~chenlab/micropostform.html).

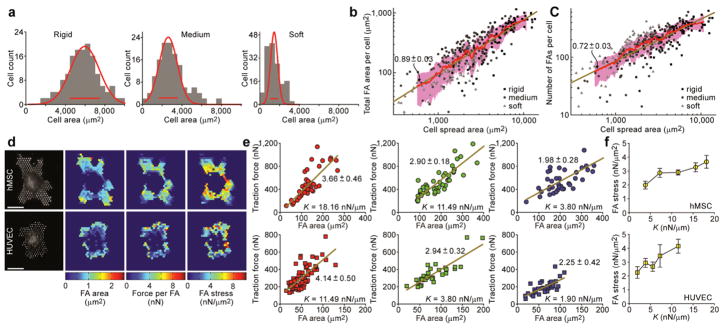

Figure 1.

Micromolded elastomeric micropost arrays to engineer substrate rigidity. (a) Graphical depiction of finite-element method (FEM) analysis of microposts of different heights L each bending in response to applied horizontal traction force (F) of 20 nN (see Online Methods). (b) Micropost deflection δ is plotted as a function of F for microposts of heights used in (a), as calculated by FEM analysis. (c) Nominal spring constant K as a function of L, as computed from FEM (bars), and from the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory (dark yellow curve). K measures micropost rigidity. (d–f) Scanning electron micrographs of hMSCs plated on PDMS micropost arrays of the indicated heights. White rectangles show where the bottom images were taken. Scale bars: 100 μm (top), 50 μm (bottom left), 30 μm (bottom middle), and 10 μm (bottom right).

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) have previously been shown to respond to microenvironmental cues6,11. We examined how hMSCs cultured on micropost arrays would respond to changes in micropost rigidity. On rigid microposts, hMSCs were well-spread (Fig. 1d) with prominent, highly organized actin stress fibers and large focal adhesions (FAs) (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, cells on soft microposts displayed a rounded morphology with prominent microvilli (Fig. 1f), disorganized actin filaments, and small adhesion complexes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Morphometric analysis of cell populations revealed strong correlation between FAs and cell spreading, regardless of micropost rigidity (Fig.2a–c). We further observed strong correlation between traction force and cell spreading, with a substantially smaller independent effect of micropost rigidity on traction force (SupplementaryFig.3). Overall, these observations suggested that cell shape, FA structures, and cytoskeletal (CSK) tension were tightly coupled systems involved in rigidity sensing. The responses were similar to those reported on hydrogels of varying rigidities, but they further suggest that rigidity sensing occurred at a micrometer scale, likely between FAs, since the nanoscale mechanics at the top of individual microposts (which could directly impact adhesion receptor binding) remain unchanged.

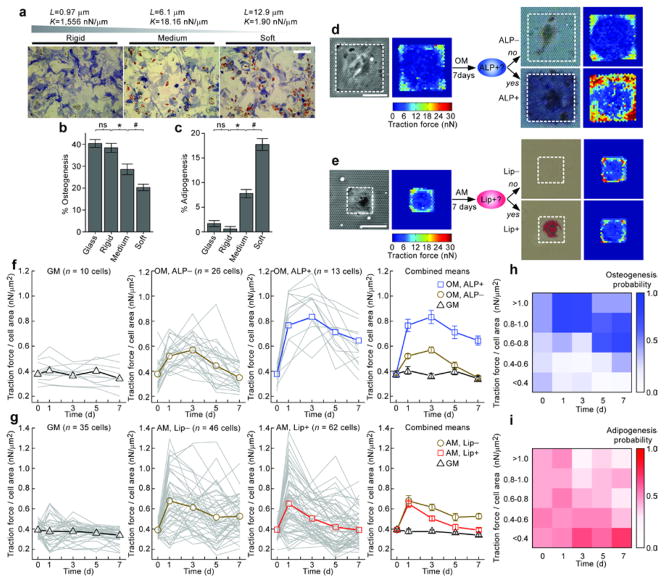

Figure 2.

Quantitative analysis of cell morphology, FA, and traction force during rigidity-sensing. (a) Distributions of cell area for hMSCs plated on micropost arrays of different rigidities (rigid: L = 0.97 μm, k = 1,556 nN/μm; medium: L = 6.1 μm, k = 18.16 nN/μm; soft: L = 12.9 μm, k = 1.90 nN/μm). Gaussian functions (red curves) were used for fitting, and red bars centered on the mean and indicated peak widths. (b–c) Total FA area (b) and total number of FA sites (c) per single hMSCs plotted against hMSC area, for three different micropost arrays as indicated. Each data point represents an individual cell (n =322 cells). Data trends are plotted as Gaussian-weighted moving averages (red curves) ± one s.d. (pink regions), and are compared with the linear least square fitting (dark yellow lines, slope values are indicated). (d) Quantification of FA area and traction force for hMSCs (top) and HUVECs (bottom) plated on the micropost arrays. Scale bars, 30 μm. (e) Traction force per single cell is plotted as a function of FA area per single cell, for both hMSCs (top) and HUVECs (bottom) plated on micropost arrays of different rigidities. Each data point represents an individual cell. Linear least square fits are plotted as dark yellow lines with slope values indicated. (f) FA stress as determined by slope values of the linear least square fits in (e) plotted against micropost rigidity K, for both hMSCs (top) and HUVECs (bottom). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Another advantage of micropost arrays over hydrogels was that measured subcellular traction forces could be attributed directly to FAs. This enabled us to map traction forces to individual FAs and spatially quantify subcellular-level distributions of FA area, traction force, and FA stress (defined as the ratio of traction force to corresponding FA area) (Fig.2d). Although previous studies have suggested the existence of smaller FAs experiencing greater stresses12, it remains unclear how these FAs are spatially organized. We observed that FA stress was not uniform across single hMSCs. Stresses on interior FAs were noticeably higher compared to those exerted on peripheral FAs. This anisotropic distribution of FA stress appeared to result from both enhanced traction force in the interior and larger FAs at the periphery. A similar analysis for human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) revealed a distinct pattern, with both enhanced traction forces and large FAs at the periphery, leading to a relatively uniform FA stress distribution (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, we observed that average FA stress per cell increased with micropost rigidity for both hMSCs and HUVECs, but to different magnitudes for the two cell types (Fig. 2e, f). These differences between cell types suggest that there may be multiple ways for cells to mechanically adapt to their environment.

To investigate whether micropost rigidity could regulate stem cell lineage commitment, hMSCs were plated on micropost arrays with different post heights L, and were exposed to either a basal growth medium (GM) or a bipotential differentiation medium (MM) supportive of both osteogenic and adipogenic fates11,13. hMSCs cultured in GM did not express differentiation markers at any micropost rigidity (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In contrast, following a two week induction in MM, we observed substantial osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation on micropost arrays, indicated by alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) and formation of lipid droplets (Lip), respectively11,13 (Fig. 3a). Importantly, micropost rigidity shifted the balance of hMSC fates: osteogenic lineage was favored on rigid micropost arrays whereas adipogenic differentiation was enhanced on soft ones.

Figure 3.

Micropost arrays regulated and predicted hMSC differentiation. (a) Brightfield micrographs of hMSCs stained for ALP and Lip after 14 days of culture in MM on micropost arrays of different rigidities. Scale bar, 300 μm. (b–c) Mean percentages of hMSC osteogenesis (b) and adipogenesis (c) as a function of micropost rigidity. Glass served as a control. Error bars, ±s.e.m. (n ≥ 3). b–c: ns (P > 0.05), *, # (P < 0.05); Student’s t-test. (d–e) Brightfield micrographs and corresponding traction force maps of micropatterned single hMSCs exposed to OM (d) or AM (e) for 7 days, and then stained for ALP (d) or Lip (e). White rectangles in micrographs highlight cell boundaries. Scale bars, 50 μm. (f–g) Evolution of traction forces (normalized to cell area) for individual micropatterned hMSCs (thin gray lines) and population means (bold lines with marker symbols) under different culture conditions as indicated. Staining is either for ALP (f) or Lip (g). Cells were grouped by medium treatment (GM, OM, or AM) and histological staining outcome (ALP+, ALP−, Lip+, or Lip−). Error bars, ±s.e.m. (h–i) Probability of differentiation of single hMSCs towards either osteogenesis (h) or adipogenesis (i) as a function of traction force (normalized to cell area) at different times.

To further confirm these histological studies, we used quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to detect changes in gene expression of osteogenic (ALP, bone sialoprotein (BSP), and frizzled B (FrzB)) and adipogenic (CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein alpha (CEBPα), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ)) markers14,15 (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). Consistent with the histological data, ALP, BSP, and FrzB were all highly induced in hMSCs on the rigid micropost arrays, while CEBPα, LPL, and PPARγ were all upregulated on the soft ones. Thus, micropost rigidity switched hMSCs between osteogenic and adipogenic lineages. The mechanism by which this rigidity-dependent switch occurred is not yet fully understood. It is likely that the observed effects of rigidity on cell shape and cytoskeletal contractility (Fig. 2) are involved, as we have previously shown11.

Although cytoskeletal contractility has been shown to affect stem cell fates, it remains unclear whether endogenous cytoskeletal contractility of individual hMSCs is predictive of differentiation. One unique feature of the micropost system is the ability to track traction forces of individual cells over the period of an experiment, and longitudinally pair those measurements to an endpoint response measured for the same cells. We patterned single hMSCs on isolated adhesive islands of microposts, which not only restricted direct cell-cell interactions and homogenized cell shape but also permitted tracking of individual cells without the added difficulty of accounting for cell migration. hMSCs patterned on large islands to promote cell spreading were exposed to GM or an osteogenic medium (OM), and less spread cells on small islands were exposed to GM or an adipogenic medium (AM). Live traction forces were assayed every other day for a period of seven days. At Day 7, we assayed commitment of single hMSCs to osteogenic or adipogenic lineage by staining for ALP (Fig. 3d) and Lip (Fig. 3e), respectively. We observed a strong correlation between traction forces and the ultimate differentiation status of individual hMSCs: in OM, hMSCs that underwent osteogenic differentiation (ALP+) demonstrated higher traction forces than the non-differentiating cells (ALP−) or the GM-treated controls; hMSCs that did not differentiate into adipocytes in AM (Lip−) were more contractile than either adipogenic hMSCs (Lip+) or the GM control. While these differences in hMSC commitment were only apparent after one week of induction, heterogeneities in traction force responses emerged substantially earlier (Fig.3f, g). OM treatment led to up-regulation of sustained traction forces as early as Day 1 for hMSCs that would ultimately become ALP+ at Day 7, while increases in traction forces for non-differentiating cells (ALP−) were significantly less (Fig. 3f). Adipogenic induction up-regulated traction force for both differentiating and non-differentiating hMSCs after only one day of exposure (Fig.3g). However, this increase in traction force decayed rapidly after Day 1, particularly in cells that ultimately committed toward the adipogenic fate (Lip+).

Enhanced contractility arising in osteogenic hMSCs within one day of OM stimulation suggested that there might be a window of early CSK responses critical for the later differentiation response. To test this possibility, we treated hMSCs with the reversible Rho kinase inhibitor, Y-2763212, for different durations during osteogenic differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 5). Indeed, brief treatments of hMSCs with Y-27632 for either 12 hrs or one day effectively decreased hMSC osteogenesis at Day 7. Thus, our studies revealed the importance of very early cytoskeletal responses in the hMSC differentiation process.

To investigate the predictive power of the evolution of traction forces for fate decisions of hMSCs at the single cell level, we performed Bayesian classifier analysis (Fig.3h, i Supplementary Fig. 6, and Supplementary Note). The posterior probability Pp of the highly contractile hMSCs in OM (f = F/A > 0.8; F/A, traction force F normalized by cell spread area A) at either Day 1 (Pp(ALP+ | fDay1 > 0.8) = 0.81) or 3 (Pp(ALP+ | fDay3 > 0.8) = 0.77) becoming ALP+ cells by Day 7 were significantly greater than the basal prior probability for osteogenesis, POsteo(ALP+) = 0.33. Similar analysis revealed that the least contractile hMSCs at Days 1 and 3 (Pp(Lip+ | fDay1,3 < 0.4) = 0.87) or Days 1, 3 and 5 (Pp(Lip+ | fDay1,3,5 < 0.4) = 0.96) were more likely to commit to adipogenesis in AM by Day 7 as compared to the basal probability for adipogenesis, PAdipo(Lip+) = 0.57 (Supplementary Fig. 6). These data showed for the first time that commitment of hMSCs at the single cell level could be predicted a priori by monitoring the evolution of their contractile states. Such early, non-invasive predictors of cell fate decisions might have utility in accelerating stem cell differentiation studies, for example in the context of drug screening, diagnostics, and regenerative medicine. These early variations in mechanical responses also suggested that subpopulations of hMSCs either were predetermined or rapidly developed distinct developmental potentials, which highlights the need for deeper understanding of the subtle layers of heterogeneity in cell populations.

In this work, we introduced a library of micromolded elastomeric micropost arrays to precisely regulate substrate rigidity, and demonstrated that this rigidity could impact cell morphology, FA structures, CSK contractility, and stem cell differentiation. This library of elastomeric micropost arrays provides an accessible, practical methodology for mechanobiology and allows real-time monitoring of cellular traction forces, a critical component of cell-material interactions that we had shown here to non-destructively predict hMSC fate decisions at the single cell level. The capability to control and predict cellular responses to a material, based on simple surface microtextures, might suggest novel coating methods for engineering the bioactivity of materials.

ONLINE METHODS

Design and fabrication of PDMS micropost arrays

Previous studies from our group, which characterized different fabrication approaches and specific geometries in a variety of applications and cell types9,10, were used to develop the final design parameters for mass-production of the elastomeric PDMS micropost arrays reported here. Based on the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory approximation, we chose to fabricate silicon micropost arrays with a post diameter of about 2 μm and heights between 1–12 μm. These post diameter and heights enabled us to obtain PDMS microposts with straight sidewalls and a broad range of rigidities to which hMSCs and HUVECs appeared to respond. The center-to-center spacing between the microposts was 4 μm, regardless of the micropost heights. This spacing between the microposts was small enough to have a minimal effect on normal cell adhesion and function, but large enough to prevent adjacent microposts from collapsing into each other due to post bending from cellular traction forces. The set of PDMS micropost arrays reported here had a final post diameter d of 1.83 μm and post heights L ranging from 0.97 to 14.7 μm, which resulted in a more than 1,000-fold range of rigidity from 1.31 nN/μm (L = 14.7 μm) up to 1,556 nN/μm (L = 0.97 μm).

Conventional high-resolution photolithography and deep reactive ion-etching (DRIE) techniques were used to achieve batch fabrication of a large volume of silicon micropost array masters16 (Supplemental Fig. 1a). A 5×reduction step-and-repeat projection stepper (Nikon NSR2005i9, Nikon Precision Inc., CA) was used for patterning photoresist. DRIE was performed with an inductively-coupled plasma deep reactive-ion etcher (ICP Deep Trench Etching Systems, Surface Technology Systems, Newport, UK). Heights of the microposts were controlled by varying etching time during DRIE. After stripping photoresist with the Piranha solution (4:1 H2SO4/H2O2), the dimensions of the silicon microposts were measured by surface profilometry (Prometrix P-10, KLA-Tenco Co., CA) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JEOL6320FV, JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA). Finally, the silicon masters were silanized with (tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2,-tetrahydrooctyl)-1-trichlorosilane (United Chemical Technologies, Bristol, PA) for 4 hrs under vacuum to aid subsequent release of the negative PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow-Corning, Midland, MI) template from the silicon masters.

The elastomeric micropost arrays were generated with PDMS by replica-molding as previously described10. Briefly, to make a template containing an array of holes, PDMS prepolymer was poured over the silicon micropost masters, cured at 110°C for 20 min, peeled off, oxidized with air plasma (Plasma Prep II, SPI Supplies, West Chester, PA), and silanized with (tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2,-tetrahydrooctyl)-1-trichlorosilane vapor overnight under vacuum. To generate the final PDMS micropost arrays, PDMS prepolymer was poured over the template, degassed under vacuum, cured at 110°C for 20 hrs, and peeled off the template. When peeling induced collapse of the PDMS micropost arrays, we regenerated the arrays by sonication in 100% ethanol for 30 sec followed by dry-release with liquid CO2 using a critical point dryer (Samdri®-PVT-3D, Tousimis, Rockville, MD).

Finite element method (FEM) characterization of nominal spring constant K of PDMS microposts

The commercial finite element package ABAQUS (SIMULIA, Dassault Systèmes, Providence, RI) was used to analyze deflections of the PDMS microposts under different applied horizontal traction forces (Fig. 1a). The PDMS micropost was modeled as a neohookian hyperelastic cylinder with a Young’s modulus E of 2.5 MPa, and was discretized into hexahedral mesh elements. The bottom surface of the micropost was assigned fixed boundary conditions. A horizontal load F was then applied uniformly at all of the nodes on the top surface of the micropost. Values of Von Mises stress, σv, were calculated and plotted (σv = 0.707 × [(σ1 − σ2)2 + (σ2 − σ3)2 + (σ1 − σ3)2]1/2, where σ1, σ2, and σ3 were the principle stresses in orthogonal directions) (Fig. 1a). FEM analysis was performed to determine displacement δ of the center node on the top surface of the post due to F. From the force-displacement curve (Fig. 1b), the nominal spring constant K of the PDMS micropost was determined by linearly extrapolating F to zero post deflection δ, and then computing K = dF/dδ (δ → 0). We further compared the FEM calculations of K as a function of L, with the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory approximation where K = 3πEd4/(64L3) (Fig. 1c). Although the Euler-Bernoulli theoretical predictions compared well with the FEM analysis for L greater than 5 μm, the theoretical results deviated from the FEM analysis for shorter microposts. We therefore used the values of K computed from the FEM for the remainder of this study.

Cell culture and reagents

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were maintained in growth medium (GM) consisting of low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biological, Atlanta, GA), 0.3 mg mL−1 L-glutamine, 100 units mL−1 penicillin, and 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin. Early passages of hMSCs were used in experiments (passage 3–6). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Lonza) were grown in EGM-2 (Lonza, CC-3162), and were maintained on gelatin-coated tissue culture polystyrene. Fresh 0.005% trypsin-EDTA in PBS was used to re-suspend HUVECs. For hMSC differentiation assays, hMSCs were exposed to either osteogenic differentiation medium (OM, Lonza) or adipogenic induction medium (AM, Lonza), or to a mixed differentiation medium (MM) consisting of a 1:1 ratio of OM and AM. Culture media were refreshed every 3 days in all experiments. Aphidicolin (0.5 μg mL−1; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was applied with every medium change to inhibit hMSC proliferation in single hMSC differentiation assays (Fig. 3). To block CSK contractility, ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM; Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) was applied with every medium change (Supplemental Fig. 5). MM was used in Fig. 3 as a bipotential differentiation medium supportive of both osteogenic and adipogenic fates to investigate whether micropost rigidity could regulate the lineage commitment and differentiation of hMSCs. Since osteogenesis occurs in well-spread cells while adipogenesis occurs in unspread contexts11, it was not possible to induce both fates in sufficient numbers for patterned single hMSCs cultured in MM (data not shown). Therefore in Fig. 3, patterned single hMSCs were exposed to OM and AM for osteogenesis and adipogenesis, respectively.

Culture of (patterned) cells on PDMS micropost arrays

PDMS micropost arrays were prepared for cell attachment using microcontact printing as previously described17. Briefly, to generate the stamps for patterned microcontact printing, a prepolymer of PDMS was poured over a photolithographically generated SU-8 master (Microchem, Newton, MA) on a silicon wafer. Stamps were immersed in a saturating concentration of 50 μg mL−1 fibronectin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in distilled (DI) water for 1 hr, washed three times in DI water, and blown dry under nitrogen. Fibronectin coated stamps were placed in conformal contact with UV ozone- treated, surface-oxidized PDMS micropost arrays (ozone cleaner; Jelight, Irvine, CA), to facilitate fibronectin transfer from the stamp to the PDMS micropost array. PDMS micropost arrays were labeled with Δ9-DiI (5 μg mL−1; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in DI water at room temperature for 1 hr. Following microcontact printing, protein adsorption to all PDMS surfaces not coated with fibronectin was prevented by incubating in 0.1–1% Pluronics F127 NF (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) in DI water for 30 min at room temperature. hMSCs and HUVECs were seeded in GM onto the PDMS micropost arrays and then allowed to spread overnight before other assays.

Fibronectin was used in this study primarily due to its convenience and broad applications in different surface treatments. Collagen type I was also tested and resulted in comparable results for hMSC differentiation (data not shown). Microcontact printing has proven efficient in completely transferring adhesive proteins from one surface to the other. Due to the nature of this method, the density of the adhesive molecules on the tops of the PDMS microposts is independent of the micropost heights. Using fluorescence-labeled proteins, we compared fluorescence intensity on the tops of the microposts with different heights. No apparent difference in fluorescence intensity was observed, indicating constant protein densities on the micropost tops.

Cell staining and SEM specimen preparation

For F-actin visualization, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) in PBS. F-actin was detected with fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Immunofluorescence staining of focal adhesions was performed as previously described17. In brief, cells were incubated in ice-cold cytoskeleton buffer (50 mM NaCl, 150 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 μg mL−1 aprotinin, 1 μg mL−1 leupeptin, 1 μg mL−1 pepstatin, and 2 mM PMSF) for 1 min, followed by 1 min in cytoskeleton buffer supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Detergent-extracted cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed with PBS, incubated with a primary antibody to vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and detected with fluorophore-conjugated, isotype-specific, anti-IgG secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

hMSCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and stained for alkaline phosphatase using Fast Blue RR Salt/naphthol (FBS25-10CAP, 855-20ML; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) per manufacturer instructions. To stain lipid fat droplets, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed in PBS and 60% isopropanol, stained with 3 mg mL−1 Oil Red O (O- 0625; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 60% isopropanol, and rinsed in PBS. For total cell counts, cell nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; D1306; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

SEM for cell culture samples was carried out at the CDB/CVI Microscopy Core at the school of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania. Samples were washed three times with 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), fixed for 1 hr with 2% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) in 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer, and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol concentrations through 100% over a period of 1.5 hrs. Dehydration in 100% ethanol was performed three times. After washing with 100% ethanol, dehydrated substrates were dried with liquid CO2 using the super critical point dryer. Substrates were mounted on stubs and sputter-coated with gold palladium. Samples were observed and photographed using a Philips XL20 scanning electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from hMSCs grown on the PDMS micropost arrays using RNeasy Micro Kit as specified by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). 0.5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with MMLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time PCR was performed and monitored using an ABI 7300 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR master mixture was based on AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the targets were assessed using commercially available primers and probes (ALP, Product No. Hs01029144_m1; BSP, Product No. Hs00173720_m1; FrzB, Product No. Hs00989812_m1; CEBP/α, Product No. Hs00269972_s1; LPL, Product No. Hs00173425_m1; PPARγ, Product No. Hs00234592_m1; RUNX2, Product No. Hs00231692_m1; OPN (SPP1), Product No. Hs00167093_m1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR was also performed with human GAPDH primers (Product No. Hs99999905_m1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to detect the endogenous control for relative quantifications. Data analysis was performed using the ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection Systems version 1.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Quantitative analysis of cell spread area and focal adhesions

Quantitative microscopy of FA proteins was performed using a Peltier-cooled monochrome charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (AxioCam HRM, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) attached to an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) with 20× (0.75 numerical aperture (NA); Plan-APOCHROMAT) and 40× (1.3 NA, oil immersion; EC Plan NEOFLUAR) objectives. Images were obtained using Axiovision (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging), and were processed using a custom-developed MATLAB program (Mathworks, Natick, MA). To determine spread area for each cell, a black and white cell image was generated from the image overlay of fluorescently-stained F-actin and vinculin, and the resultant white pixels were summed to quantify cell area. Briefly, the Canny edge detection method was used to binarize the actin fibers and FAs, and then image dilation, erosion, and fill operations were used to fill in the gaps between the white pixels. To quantify FA number and area for each cell, the grayscale vinculin image was thresholded to produce a black and white FA image from which the white pixels, representing FAs, were counted and summed.

Quantification of traction forces

Quantitative analysis of subcellular level traction forces was performed as previously described10,11. Briefly, the micromolded PDMS micropost arrays underlying cells were imaged with a 40×, 1.3 NA, oil immersion objective (EC Plan NEOFLUAR) and a CCD camera (AxioCam HRM) attached to an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200M). The microscope was enclosed in a live cell incubator (In Vivo Scientific, Saint Louis, MO) to maintain the experimental environment at 37°C and 5% CO2. For each cell, fluorescent images of the Δ9-DiI-stained PDMS microposts were acquired at two different focal planes. The top image was acquired at the focal plane passing through the top surfaces of the microposts, while the bottom one approximately 1 μm above the base of the microposts. These two images were analyzed with a custom-developed MATLAB program (Mathworks) to calculate traction forces. The centroids of the cross sections of the microposts in both the top and bottom images were determined by the localized thresholding algorithm (LT) described previously11. Briefly, “windows” were drawn that enclosed a single post. The region of the image within each window was converted to black and white using thresholding until the sum of white pixels that comprise the post reached the expected size of the post cross-sectional area. The centroid was then calculated from the thresholded image. Due to the close spacing of the microposts, two-dimensional (2D) Gaussian curve fitting was used to refine the centroids calculated by the LT method, particularly for strongly deflected PDMS posts, as described previously11. Briefly, the grayscale intensity profile of a PDMS micropost was modeled as 2D Gaussian fits, and the centroid was determined by a nonlinear least squares fit to this model. The top and bottom centroids calculated by these two methods represent the deflected and undeflected positions of the microposts, respectively. Using undeflected “free” posts as reference points, the top and bottom grid of post centroids were aligned to determine the deflections δ for the “attached” posts, which were then converted to the horizontal traction forces by multiplying the nominal spring constant K calculated from the FEM simulations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (EB00262, HL73305, and GM74048), the Army Research Office Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative, the Material Research Science and Engineering Center, the Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the Nano/Bio Interface Center, and the Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders of the University of Pennsylvania, and the New Jersey Center for Biomaterials (RESBIO Resource Center). J. Fu and Y.-K Wang were both partially funded by the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship. M. T. Yang was partially funded by the National Science Foundation IGERT program (DGE-0221664). We thank Pan Mao and Yuri Veklich for assistance in electron microscopy, Daniel M. Cohen for critical feedback on the manuscript, and the M.I.T. Microsystems Technology Laboratories for support in cleanroom fabrication.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

J. Fu and C. S. Chen conceived and initiated project. J. Fu and M. T. Yang designed and fabricated micropost arrays. J. Fu, Y.-K. Wang, M. T. Yang, R. A. Desai, and X. Yu designed and performed experiments, and analyzed data. Z. Liu analyzed data. All authors edited and reviewed the final manuscript. C. S. Chen supervised project.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogel V, Sheetz M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingber DE. Circ Res. 2002;91:877–887. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000039537.73816.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelham RJ, Wang YL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13661–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paszek MJ, et al. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houseman BT, Mrksich M. Biomaterials. 2001;22:943–955. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keselowsky BG, Collard DM, Garcia AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5953–5957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407356102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan JL, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1484–1489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235407100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang MT, Sniadecki NJ, Chen CS. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3119–3123. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CC. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Kaverina I, Small JV, Wang YL. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:881–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pittenger MF, et al. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aubin JE. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:899–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Ann Rev Cell Dev. 2000;16:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madou M. Fundamentals of Microfabrication. 1. CRC Press; New York, USA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirone DM, et al. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:277–288. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.