Abstract

Over the past years, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) has proven its efficacy in large clinical trials, and consequently, the assessment of function, viability, and ischaemia by CMR is now an integrated part of the diagnostic armamentarium in cardiology. By combining these CMR applications, coronary artery disease (CAD) can be detected in its early stages and this allows for interventions with the goal to reduce complications of CAD such as infarcts and subsequently chronic heart failure (CHF). As the CMR examinations are robust and reproducible and do not expose patients to radiation, they are ideally suited for repetitive studies without harm to the patients. Since CAD is a chronic disease, the option to monitor CAD regularly by CMR over many decades is highly valuable. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance also progressed recently in the setting of acute coronary syndromes. In this situation, CMR allows for important differential diagnoses. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance also delineates precisely the different tissue components in acute myocardial infarction such as necrosis, microvascular obstruction (MVO), haemorrhage, and oedema, i.e. area at risk. With these features, CMR might also become the preferred tool to investigate novel treatment strategies in clinical research. Finally, in CHF patients, the versatility of CMR to assess function, flow, perfusion, and viability and to characterize tissue is helpful to narrow the differential diagnosis and to monitor treatment.

Keywords: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, Coronary artery disease, Myocardial infarction, Acute coronary syndrome, Congestive heart failure, Computed tomography, Single-photon emission computed tomography, Echocardiography

Introduction

The prevalence for coronary artery disease (CAD) in industrialized countries is high and is estimated to range between 20 000 and 40 000 individuals per million suffering from angina in Europe.1 From large statistics in USA, it is also evident that many patients with CAD do not experience angina pectoris before their first heart attack and this fraction is ranging from ∼50% (for men) up to 67% (in women).2 Thus, an estimated 40 000–80 000 individuals per million are at risk for a heart attack at some time during their course of CAD. Over the past years, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) emerged as a powerful technique to assess myocardial ischaemia and viability, and therefore, it may become an increasingly used technique to monitor and guide treatment in the different clinical presentations of CAD. In the chronic phases of CAD, ischaemia assessment by CMR may become the key test for risk stratification, thereby helping in guiding treatment decisions (revascularizations). In the acute phases of CAD, i.e. in acute coronary syndromes (ACS), viability assessment is most important and CMR is expected to play an increasing role in differentiating ACS from other diseases such as perimyocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (CMP), or acute aortic diseases. Finally, in the end-stages of CAD, i.e. in chronic heart failure (CHF), CMR can contribute to patient management by assessing ischaemia and viability and also by excluding or confirming differential diagnoses.

In the first part of this review, we will focus on a potential role of CMR in the patient population at risk. In the second part, the review describes the possible contribution and the emerging role of CMR in the setting of acute chest pain and ACS. Finally, in the third part, the role of ischaemia and viability imaging by CMR in CHF is discussed.

Ischaemia detection

A key cardiovascular magnetic resonance application for the assessment of chronic chest pain and suspected coronary artery disease

Perfusion-cardiovascular magnetic resonance

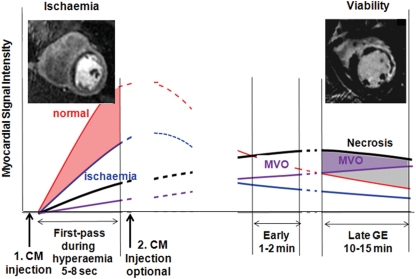

The principle of perfusion-CMR is based on the monitoring of contrast medium (CM) wash-in kinetics into the myocardium during a hyperaemic state (Figure 1). In territories supplied by significantly stenosed coronary arteries, the wash-in of CM is delayed and this is depicted as dark zones of tissue during CM first-pass, when utilizing T1-weighted pulse sequences and Gd-based CM (Table 1).3–8 As the CM first-pass lasts about 5–15 s during hyperaemia, perfusion-CMR is performed during a breath-hold to eliminate respiratory motion artefacts. To eliminate motion artefacts by cardiac contraction, the acquisition window should last <100 ms per slice. Although a spatial resolution of 1–1.5 mm × 1–1.5 mm is possible,9 a minimum of 2–3 mm × 2–3 mm is required to minimize susceptibility artefacts at the blood pool–myocardial interface5,10 (for more details, see Table 2). The read-out type of a pulse sequence [conventional or parallel imaging, fast gradient echo, (hybrid)-echo-planar, or steady-state free precession] is of minor importance as long as spatial and temporal resolutions are achieved as suggested in Table 2.5 Here, it should be mentioned that a signal increase of 250–300% (relative to pre-contrast myocardial signal) is required during hyperaemic first-pass to guarantee adequate diagnostic performance.10–12 For an example, see Figure 2.

Figure 1.

A schematic explains the various time points of image acquisition relative to contrast medium administration to assess ischaemia and necrosis/scar tissue. Red line corresponds to normal non-ischaemic myocardium, blue line the ischaemic myocardium, black line the necrotic tissue in the acute myocardial infarction (fibrotic tissue in chronic myocardial infarction), and purple line the tissue with microvascular obstruction (MVO).

Table 1.

Perfusion-cardiovascular magnetic resonance and stress dobutamine-cardiovascular magnetic resonance: diagnostic performance

| Study | n (n) | Reference | CM type/dose | Stress | Analysis | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusion-CMR | ||||||||

| Single6 | 57 | CXA (≥50%) | Gd-DTPA-BMA/0.1 mmol/kg | Dip (stress only) | Upslope subendo | 87 | 85 | 0.91 |

| Single6 | 43 | PET (CFR) | Gd-DTPA-BMA/0.1 mmol/kg | Dip (stress only) | Upslope subendo | 91 | 94 | 0.93 |

| Single7 | 92 | CXA (≥70%) | Gd-DTPA/0.05 mmol/kg | Adeno (rest/stress) | Upslope PRI | 88 | 82 | 0.91 |

| Single8 | 79 | CXA (≥50%) | Gd-BOPTA/0.05 mmol//kg | Adeno (stress/rest) | Visual | 91 | 62 | — |

| Single14 | 84 | CXA (≥75%)a | Gd-DTPA/0.025 mmol/kg | Adeno (rest/stress) | Upslope PRI | 86 | 87 | 0.92 |

| Single15 | 104 | CXA (≥70%) | Gd-DTPA/0.75 mmol/kg | Dip (stress/rest) | Visual | 90 | 85 | 0.90 |

| Single9 | 51 | CXA (≥50%) | Gadobutrol/0.1 mmol/kg | Adeno (stress only) | Visual | — | — | 0.85 |

| Multicentre16 | 50 | CXA (≥50%) | Gd-DTPA/0.05 mmol/kg | ATP (stress/rest) | Visual | 86 | 75 | 0.88 |

| Multicentre12 | 80 (24) | CXA (≥50%) | Gd-DTPA-BMA/0.1 mmol/kg | Adeno (stress only) | Upslope subendo | 91 | 78 | 0.91 |

| Low dose12 | 80 (29) | CXA (≥50%) | Gd-DTPA-BMA/0.05 mmol/kg | Adeno (stress only) | Upslope subendo | — | — | 0.53 |

| MR-IMPACT10 | 212 (42) | CXA (≥50%) | Gd-DTPA-BMA/0.075 mmol/kg | Adeno (stress only) | Visual | 85 | 67 | 0.86 |

| Stress dobutamine-CMR | ||||||||

| Single29 | 186 | CXA (≥50%) | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 86 | 86 | — |

| Single30 | 41b | CXA (≥50%) | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 83 | 83 | — |

| Single31 | 22 | CXA (≥75%)a | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 88 | 83 | — |

| Single32 | 27 | CXA (≥70%) | — | Treadmill | Visual | 79 | 85 | — |

| Single8 | 79 | CXA (≥50%) | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 89 | 80 | — |

| Single23c | 150 | CXA (≥50%) | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 78 | 87 | — |

| Single33 | 40 | CXA (≥50%) | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 89 | 75 | — |

| Single34 | 204d | CXA (≥70%) | — | Dobutamine | Visual | 85 | 86 | — |

n: in CM dose-finding studies (n) indicates participants in a specific dose group; PRI, perfusion reserve index.

aArea stenosis.

bPatients with negative dobutamine-CMR: CXA was not performed, but a follow-up of 6 months, where no cardiac death occurred.

cReproducibility study: for sensitivity and specificity, means are given.

dWomen only.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance applications

| MR modality | Types of diagnoses possible | Parameters | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localizer images | Aortic dissection | fGRE sequences or SSFP sequences | 1–2 min |

| Aortic aneurysm | |||

| Pleural effusion | fGRE with and without fat saturation (to detect or exclude fatty infiltration in ARVC) | ||

| Large pneumonia | |||

| Intrathoracic masses | |||

| Congenital heart diseases | |||

| ARVC | |||

| Cine CMR | Global LV or RV function abnormalities | Spatial resolution: 1–2 mm × 1–2 mm | 5–10 min |

| Regional wall motion abnormalities | Temporal resolution: 40–60 ms | ||

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Preferred sequence type: SSFP | ||

| LV aneurysms | Slice thickness: 6–10 mm, gap 0–2 mm | ||

| Pericardial effusion | |||

| Valve abnormalities (valve orifice) | |||

| Congenital heart diseases | |||

| Stress perfusion-CMR | Ischaemia detection | Spatial resolution: at least 2–3 mm × 2–3 mm to minimize susceptibility artefacts along the blood pool–myocardial interface | 10 min |

| Hyperaemia | Stress induced perfusion deficit (adenosine, dipyridamole) | Temporal resolution: 1 short-axis stack/1–2 beats | |

| Adenosine: 0.14 mg/kg/min for 3 min | Stress induced segmental dysfunction (cine CMR with dobutamine) | Acquisition window/slice: <100 ms to minimize cardiac motion artefacts | |

| Dipyridamole: 0.56 mg/kg for 4 min | Detection of CAD | Signal increase during first-pass: >250–300% | |

| CM: 0.075–0.10 mmol/kg injected at 5 mL/s into cubital vein | Work-up of patients with known CAD for treatment decisions | 90°-preparation delay time: 100–150 ms/slice | |

| Work-up of patients after CABG | Coverage: ≥3 short-axis slices | ||

| Risk stratification in CAD | Slice thickness of 8–10 mm | ||

| Stress dobutamine-CMR | Sequence: see cine CMR | 10–20 min | |

| Dobutamine doses of 10/20/30/40 µg/kg (for 3 min each). Atropine up to 2 mg is added, if target heart rate (220-age) is not reached | 3 short-axis and 3 long-axis acquisitions per dose of dobutamine | ||

| Rest perfusion | Rest myocardial ischaemia/abnormal perfusion | Sequence: see stress perfusion-CMR | 1 min |

| Microvascular obstruction | |||

| Tumour (differentiation vs. thrombus) | |||

| Early gadolinium enhancement | Microvascular obstruction | Pulse sequences: see LGE | 1–10 min |

| No reflow phenomenon | |||

| Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) | MI | Spatial resolution: 1.5–2.0 mm × 1.5–2.0 mm | 5–15 min |

| Myocardial fibrosis | Preferred sequence type: segmented inversion recovery (IR) fGRE | ||

| Myocarditis | Slice thickness: 5–8 mm, gap 0–4 mm | ||

| Various non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies | CM: 0.15–0.2 mmol/kg i.v. | ||

| Thrombus | Start of imaging: 10–20 min after CM injection | ||

| Amyloidosis | |||

| T2-weighted CMR | Ischaemic area at risk | Preferred sequence type: segmented fast spin echo (with double inversion: dark blood) or STIR | 5 min |

| Myocardial oedema due to inflammation | |||

| Intramyocardial haemorrhage (in AMI) | |||

| Myocarditis | |||

| Takotsubo | In progress: T2-prepared single-shot SSFP for T2 maps | ||

| Differentiation of acute vs. old infarction | |||

| MR angiography | Aortic dissection | 3D acquisition during breath-hold, typically untriggered | 10 min |

| Aortic aneurysm | Spatial resolution: 1–2.5 mm × 1–2.5 mm | ||

| Pulmonary embolus | CM: 0.1–0.2 mmol/kg at 2–3 mL/s i.v. | ||

| Congenital heart diseases | |||

| MR coronary angiography | Coronary anomalies | Free-breathing T2-prep. 3D navigator-gated fGRE | 20–30 min |

| Coronary stenosis (sometimes) | Spatial resolution: 1 mm × 1 mm × 1.5 mm | ||

| Breath-hold technique for proximal coronaries | |||

| CMR flow | Insufficient (stenotic) valves | Spatial resolution: >8 pixels per vessel diameter | 2–5 min |

| Shunts | Velocity encoding ∼120% of expected peak vel. | ||

| Congenital heart diseases | |||

| T2*-weighted CMR | Iron overload, e.g. in thalassaemia | Spoiled gradient multi-echo T2* sequence (normal myocardial T2* > 20 ms) | 2–5 min |

| Intramyocardial haemorrhage (in AMI) | |||

CMR provides a multimodal integrated assessment of patients with suspected CAD, possible or definite ACS, and CHF. Selection of different imaging modalities should be customized to the likely diagnoses and individualized to a given patient. Time estimates are rough estimates. ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CM, contrast medium; fGRE, fast gradient echo; SSFP, steady-state free precession.

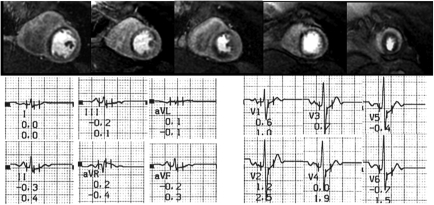

Figure 2.

Example of a 70-year-old female patient with atypical chest pain and mild dyspnoea during exercise. Risk factors were hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes. The patient performed at 100% of predicted workload without symptoms and with a normal stress electrocardiogram (mildly ascending 0.07 mV ST depression) and without arrhythmias. Perfusion-cardiovascular magnetic resonance detects severe ischaemia in all vascular territories. Coronary angiography confirmed a triple-vessel disease and the patient was treated successfully by multiple stenting.

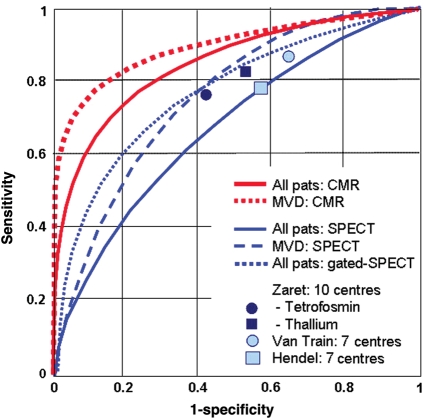

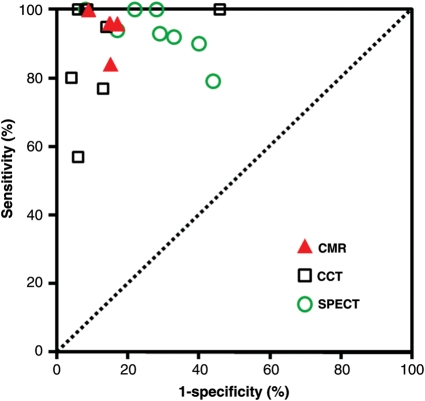

In comparison with 13NH3-PET as the reference standard, sensitivity and specificity for ischaemia detection by CMR were 91 and 94%, respectively, and for detection of ≥50% diameter stenoses, sensitivity and specificity were 87 and 85%, respectively [area under the receiver operator characteristics curve (AUC): 0.91].6 Similar results were obtained in other single-centre studies13–16 (Table 1). For perfusion-CMR, CM doses of 0.10 mmol/kg (or ≥0.075 mmol/kg) are recommended.5,10,12 The largest perfusion-CMR trial published so far is MR-IMPACT.10 In 18 centres in Europe and USA, perfusion-CMR detected CAD with an AUC of 0.86 (sensitivity and specificity of 86 and 67%, respectively). In comparison with the entire single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) population, perfusion-CMR performed superior vs. SPECT (Figure 3). This superiority was also shown for multivessel disease CAD. Of note, SPECT performance in the MR-IMPACT was also well comparable with the results of earlier multicentre SPECT studies, which used conventional X-ray coronary angiography as the standard of references reporting sensitivities and specificities of 77–87 and 36–58%, respectively (Figure 3).17–20 We would like to mention, that in the MR-IMPACT, no attenuation correction of SPECT data was performed, which is known to improve specificity. The diagnostic performance of perfusion-CMR was confirmed later in the MR-IMPACT II study performed in 33 centres in Europe and USA.10 For both, perfusion-CMR and stress dobutamine-CMR, a moderate to high reproducibility could be shown (with interobserver κ values of 0.70–0.7321,22 and 0.59–0.81,21–23 respectively).

Figure 3.

Diagnostic performance of perfusion-cardiovascular magnetic resonance to detect coronary artery disease (defined as ≥50% stenosis in invasive coronary angiography) in comparison vs. SPECT. Performance of SPECT in MR-IMPACT is comparable to those of previous multicentre SPECT trials (given as squares and circles) reported by Zaret et al.,20 Van Train et al.,18 and Hendel et al.17 Better performance is obtained with perfusion-cardiovascular magnetic resonance vs. SPECT [P < 0.013, in multivessel disease (MVD) P < 0.006]. Modified from Schwitter et al.10 with permission of Oxford Press.

Perfusion-CMR performed at 3 T yielded similar results as was observed for 1.5 T.24 As no multicentre data on 3 T performance are available to date, for clinical perfusion-CMR, the 1.5 T equipment is recommended. Similarly, no multicentre data are available comparing visual analysis with quantitative approaches (e.g. by using upslope data). For perfusion data sets acquired with parameters as stated in Table 2, a high image quality will be obtained and similar diagnostic performances are likely to be achieved by both visual and quantitative approaches (Table 1). The relationship of data quality and acquisition strategies is currently under investigation within the European CMR registry.25 Regarding the perfusion protocol, a high diagnostic performance was reported in several studies by analysis of the hyperaemia data only (Table 1), which favours a stress-only protocol.6,9–12 Adenosine induces maximal hyperaemia at 0.14 mg/min/kg body weight (administered i.v. over 3 min), is characterized by a short half-life (<10 s), and is safe (1 infarction in >9000 examinations, no death),26,27 and therefore, it is currently one of the most commonly used agents in pharmacological stress testing. A novel selective A2A agonist regadenoson received approval for pharmacological stress testing in the USA and is likely to be available in Europe soon. This novel drug class is easier to use (e.g. injected as a single bolus); first reports demonstrate a high safety profile, and similar diagnostic accuracy was achieved as with conventional vasodilators when combined with scintigraphy.28

Stress dobutamine-cardiovascular magnetic resonance

A powerful alternative to perfusion-CMR is stress dobutamine-CMR which detects ischaemia by monitoring regional wall motion during infusion of increasing doses of dobutamine. This principle is identical to stress echocardiography, but the CMR technique benefits from consistently good to high image quality in a very high percentage of patients. In a landmark paper, dobutamine-CMR performed better than stress echocardiography, where the difference in diagnostic performance was particularly evident in patients with reduced echo quality.29 Since then, a large number of studies demonstrated the high sensitivity and specificity of dobutamine-CMR to detect CAD (Table 1).23,30–34 The CMR protocol is well established,5 the inotropic stimulation by dobutamine is following mainly that for stress echocardiography (see also Table 2), and it is safe.35 The consistently high image quality is also reflected by an excellent reproducibility of this test.21,23

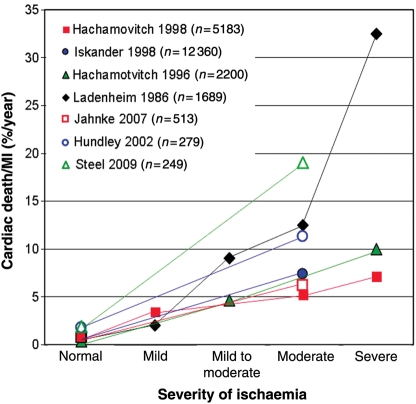

Over the last few years, also outcome data after stress dobutamine-CMR could be collected demonstrating a very low event rate in patients without ischaemia,36 and this result was later confirmed by other groups (Figure 4).22 In a study comparing perfusion-CMR with stress dobutamine-CMR, a predictive value for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was similar for both techniques indicating that both ischaemia tests might be similar in performance.22

Figure 4.

Prediction of cardiac death and non-fatal myocardial infarction by assessment of ischaemia in seven large studies comprising more than 20 000 patients. In patients without ischaemia, outcome is excellent.

Complication management vs. risk management: the pivotal role of ischaemia detection

Up to now, cardiologists typically concentrated on symptomatic patients and treatment was aimed to alleviate angina or to manage acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in order to reduce infarct size and to avoid cardiac death. This paradigm therefore is based on the management of complications of CAD. However, the treatment of complications of CAD such as AMI and sudden cardiac death is not always successful and it is costly. With the advent of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in AMI, the death rate of AMI could be reduced in in-hospital patients, but it remains still high during the outpatient phase of AMI which underlines the need for early CAD detection.2 As a consequence, the paradigm of a ‘complications management’, i.e. to treat symptomatic patients and AMI, should evolve into a ‘risk management’ approach, which focus on early detection of CAD and consequently on treatment and revascularization of (symptomatic or asymptomatic) CAD to prevent infarctions.37 Updated guidelines therefore recommend to assess risk not only based on symptoms, but also on gender and risk factors, as well, and to revascularize based on the extent and severity of ischaemia.38 High-risk patients should proceed to invasive angiography directly, whereas intermediate-risk patients with a likelihood for obstructive CAD of 20–80% (or 10–90%) should undergo ischaemia testing. In patients without ST-segment changes in the resting electrocardiogram (ECG) and which can exercise adequately, a stress ECG is still the first-line method to use.38 Intermediate-risk patients post-exercise5,39 are then candidates for non-invasive imaging tests such as SPECT, stress echocardiography, perfusion-CMR, or stress dobutamine-CMR to confirm or exclude ischaemia.38 Figure 4 illustrates the prediction of cardiac death and non-fatal MI by non-invasive ischaemia detection compiled from seven large studies in more than 20 000 patients.22,36,40–44 The evidence for the prognostic value of SPECT40–43 is large, and a few studies are available for CMR as well.22,36,44 These large-scale data given in Figure 4 demonstrate that in patients without ischaemia, complication rates are very low, justifying a conservative approach focusing on risk factor management.

How does this statement relate to the theory that often non-obstructive plaques are vulnerable? Here, it appears important to note that not all plaque ruptures result in infarctions.45,46 The repeated rupture of vulnerable plaques is most likely the mechanism of disease progression, whereas plaque rupture with consequent vessel occlusion is the event that directly drives outcome (such as cardiac death and non-fatal MI).45–47 As can be seen in Figure 4, ischaemic patients with haemodynamically relevant plaques are at a particularly high risk for infarctions, i.e. for plaque ruptures that cause acute vessel occlusions. Also, an invasive study in more than 4000 patients with stenosis of <50% diameter reduction yielded an event rate for cardiac death/non-fatal MI as low as 1.1%/year,48 whereas an increasing degree of stenosis on invasive coronary angiography was associated with an increasing risk for infarctions.49,50 These data and particularly those from non-invasive imaging (Figure 4) clearly confirm that ischaemia (i.e. its extent and severity) is a most powerful predictor for future infarctions,22,36,41–44,51 and ischaemia detection takes a central position in the current guidelines.38,52

Since CAD is a chronic disease with relatively stable phases that can be interrupted by episodes of disease progression (plaque ruptures) and complications (plaque ruptures with occlusions), the monitoring of disease activity requires a test, which can be repeated whenever a disease progression is suspected. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance can be repeated theoretically whenever needed since it is not exposing patients to any ionizing radiation. This is an important advantage of CMR over SPECT or multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). Perfusion assessment by CMR requires one CM administration during hyperaemia, which results in short examination times of <1 h. In addition, perfusion-CMR is not hindered by stents in the coronary arteries, so that patients can be monitored after PCI. As PCI are associated with X-ray exposures, and most patients will also need other X-ray-based examinations during their life time, it is most reasonable to avoid X-ray exposure in these patients whenever possible.53,54 Cardiovascular magnetic resonance is entering now the routine work-up of patients as shown in the European CMR registry data with >11 000 patients included, where CMR findings changed diagnosis and consequently further work-up and/or treatment in ∼60% of the cases.55

Viability assessment

Although a successful risk management strategy should avoid MI, this concept will not always prevent CAD complications, and as a consequence, viability assessment will then be required.

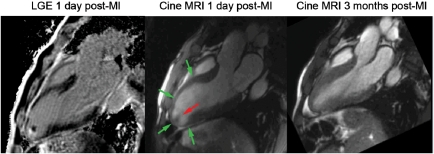

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance applications in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: impact on clinical management and on research

The diagnosis and management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is well established,56 and in general, there is no routine need for non-invasive imaging in STEMI during early phases of presentation, except, for example, in suspected aortic dissection, where echocardiography, CT, or CMR is required. Echocardiography is also helpful in suspected cardiac tamponade or mechanical complications of AMI and CMR is also valuable in detecting intracardiac thrombus complicating AMI (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Viability assessment by late gadolinium enhancement (A) demonstrates the absence of necrosis (lack of bright tissue) in the hypo-akinetic anterior wall [end-systolic image in (B)]. As expected, the follow-up assessment by cardiovascular magnetic resonance demonstrates a major recovery of contractile function in the anterior wall [(C) end-systolic images at follow-up]. The late gadolinium enhancement technique is also sensitive for detection of thrombus, which is attached to a small necrotic (=bright) area in the apex of the left ventricle (A).

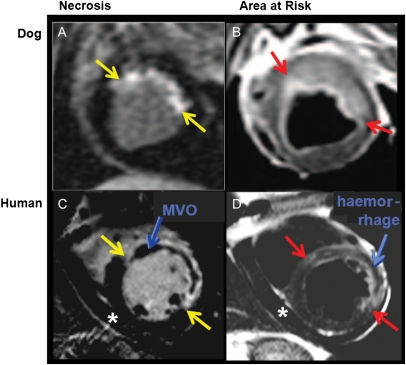

Since CMR is an excellent tool for tissue characterization, it offers unique applications in the field of AMI and, in particular, in AMI research. Necrosis can be visualized by CMR with excellent contrast and with submillimetre resolution allowing for detection of microinfarcts well below 1 g of mass.57,58 This late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) technique59 is now widely accepted as an excellent way to assess viability in both acute and chronic MI. The current-generation gadolinium-based CM (with one exception) are described as extracellular agents. This means that the gadolinium chelates rapidly distribute within the intravascular and interstitial space but are excluded from the intracellular space (Figures 1 and 6). Because the cell membranes of infarcted myocardium can no longer exclude the contrast from the intracellular space, over the course of 10–20 min, acutely infarcted myocardium enhances to a much greater extent than viable myocardium (Figures 1 and 6A and C).60,61 Thus, LGE imaging quantifies the extent and severity of myocardial injury after acute reperfused infarction.60,62–65 Recently, phase-sensitive strategies for LGE imaging were introduced (phase-sensitive inversion recovery) that further improved the robustness of CMR viability imaging. In large infarcts, particularly when non-reperfused, microvascular obstruction (MVO) is visualized by the LGE approach as a dark core residing within a bright infarct zone.66–68

Figure 6.

Tissue characterization by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. On the left-hand side (A and C), late gadolinium enhancement is applied to delineate tissue necrosis as bright areas (red arrows). In the canine experiment, a small subendocardial necrosis is detected, whereas in the patient with acute myocardial infarction (C), a dark core in the centre of necrosis is indicating the presence of microvascular obstruction. On the right, T2-weighted images show increased signal in the myocardium, indicating the presence of oedema, which corresponds to the area at risk. In the patient (D), dark areas in the centre of oedematous tissue indicate haemorrhage. The oedematous tissue [bright on T2-weighted images in (B) and (D)], i.e. the area at risk minus the necrotic tissue [in (A) and (C), respectively] yields the amount of salvaged myocardium.

Several studies have validated LGE vs. biomarker release such as CK, CKMB, and troponin in the setting of acute or subacute MI.57,67,69,70 The amount of LGE is inversely related to the eventual left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction and the transmural extent of infarction predicts the likelihood of recovery of regional wall motion (Figure 5). Comparative studies with SPECT58,71 and PET72–74 suggest significant advantages for CMR due to the increased spatial resolution of CMR compared with nuclear methods. Furthermore, LGE has excellent sensitivity and specificity even in the difficult setting of multicentre trials.75,76

Thus, in the field of AMI research, CMR is becoming increasingly important as it allows for accurate and reproducible quantification of global and regional LV function, and also for the quantification of necrosis/scar tissue and MVO (Table 2 and Figure 6). Recently, an elegant approach was proposed to assess the amount of myocardium at risk. By means of T2-weighted CMR, Aletras et al.77 demonstrated a close relationship between the amount of tissue oedema in the myocardium and the area at risk as assessed by microspheres (Figure 6A and B). Novel pulse sequences are available now to increase the robustness of T2-weighted oedema imaging by means of T2 maps.78 By subtracting necrotic tissue from the tissue at risk, a myocardial salvage index can be calculated, which was successfully applied to demonstrate that the amount of salvaged myocardium in AMI patients is inversely related to the time delay from pain onset to PCI.79 This index was also shown to predict MACE.80 Another type of tissue injury, intramyocardial haemorrhage, can be visualized. Haemorrhage influences the T2 properties of tissue and consequently low signal areas on T2-weighted images were shown to correspond to haemorrhage on histology.81,82 An example is given in Figure 6D. A heterogeneous distribution of the various degradation products of haemoglobin also modify local magnetic field properties and T2*-weighted sequences might be even more sensitive for the quantification of haemorrhage.83 The presence of haemorrhage in the core of the infarcted area might influence the healing processes and Ganame et al.84 could observe an adverse remodelling of the LV in patients after PCI, when haemorrhage was present in the infarct core.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute chest pain patients and in acute coronary syndromes

Although STEMI diagnosis is straightforward in emergency departments (ED), a relatively small fraction, typically <10%, of the patients with chest pain actually have STEMI and/or an ischaemic ECG and the great majority does not have ACS.85 Thus, the ED physician is faced with a daunting task of separating life-threatening diseases such as ACS, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism from other aetiologies that might not require immediate hospitalization. In acute chest pain, the ACCF/AHA Guidelines on ACS86 recommend a non-invasive approach in patients with severe co-morbidities and in those with a low likelihood for ACS. Similarly, the ESC guidelines recommend non-invasive imaging in acute chest pain with repetitive negative troponins and normal or undetermined ECGs.87 As shown in Figure 7, non-invasive imaging can improve sensitivity of detecting unstable angina/non-STEMI (NSTEMI) and other causes of chest pain. The first major clinical trial assessing the diagnostic performance of CMR in the ED (in patients with 30 min of chest pain and no ST elevation) detected MI with a sensitivity and specificity of 100 and 79%, respectively, and many of those false-positive cases turned out to have unstable angina.88 The primary endpoints, NSTEMI and unstable angina, were detected by CMR with a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 85%. Cury et al.89 incorporated T2-weighted imaging into the protocol to differentiate acute from chronic wall motion abnormalities, which improved the overall results to a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 96%.

Figure 7.

Performance of different imaging techniques to detect acute coronary syndromes in acute chest pain patients. Data are derived for cardiovascular magnetic resonance from references,88–91 for computed tomographic angiography from references,106–111 and for SPECT from references.103,112–118

Ingkanisorn et al. studied 135 patients with acute chest pain who had MI excluded by serial ECG and troponin-I. In these patients, adenosine perfusion-CMR, performed within 72 h of presentation, yielded the highest sensitivity and specificity (100 and 93%, respectively) of any single CMR protocol component.90 In addition, no patients with a negative CMR scan had any cardiovascular outcomes in a 1-year follow-up. A large percentage of patients with an abnormal perfusion-CMR had the diagnosis confirmed by other testing, required revascularization, or suffered from an MI during follow-up. Plein et al.91 studied NSTE-ACS and adenosine perfusion-CMR, performed within 72 h of presentation, yielded the highest sensitivity and specificity for significant coronary stenosis detection of 88 and 83%, respectively, which increased to 96 and 83%, respectively, by using images of diagnostic quality only. Recently, CMR was shown to reduce the overall cost of evaluating patients with intermediate-risk chest pain.92

With regard to feasibility of using CMR in the ED setting, in the study by Kwong et al.,88 a total of 11% were excluded (5% because of claustrophobia). Weight and body size are not significant limitations in centres with high-performance wide-bore scanners. There remain other significant barriers to the use of CMR in the routine assessment of chest pain in the ED including limited ability to accommodate emergency studies, limited availability of infrastructure needed to perform the relatively complex cardiac CMR scans, and limited availability of experienced technologists and physicians.

Differential diagnoses of acute coronary syndromes

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance is very useful to exclude or confirm conditions that can mimic NSTE-ACS or unstable angina. In these patients with chest pain and troponin elevations, but normal coronary angiography, CMR could yield findings typical for myocarditis in 30–50% of the cases.93–95 In Takotsubo CMP characterized by anginal symptoms, ECG changes, and normal coronary anatomy, echocardiography or CMR can demonstrate the typical akinetic or dyskinetic motion of the apex. In addition, in Takotsubo CMP, the LGE technique can demonstrate tissue viability and exclude myocarditis, which consequently predicts the well-preserved prognosis in these Takotsubo patients.96–98 In addition, oedema formation was found in these patients by T2-weighted CMR imaging.99

Finally, CMR can be applied to detect or exclude acute diseases of the aorta such as dissection, penetrating ulcers, or intramural hematoma.5,100 However, it should be mentioned that CT is the primary method for the assessment of acute diseases of the aorta or for the ‘triple-rule-out’ strategy due to its speed and the ease of utilization.

In patients with acute chest pain, echocardiography can detect regional wall motion abnormalities and, when combined with CM, can detect perfusion abnormalities. The sensitivity of wall motion abnormalities in patients with AMI range from 88 to 92% which is generally lower than thresholds desired by ED physicians.101,102

Single-photon emission computed tomography imaging can also be used to evaluate patients with chest pain syndromes in the ED. Multicentre clinical trials support the conclusion that SPECT imaging adds a diagnostic value above clinical evaluation103 and reduce the cost of evaluation compared with short hospitalizations to evaluate low-risk patients.104 At the same time, these studies also document the imperfect sensitivity for short-term cardiac events defined as emergency revascularization, MI, or death.103,104 Even in a relatively low-risk population, SPECT missed 3% of AMI in the ED.

Multiple MDCT angiography studies have shown sensitivities and specificities for CAD detection that exceeds generally accepted statistics for any of the stress test modalities.105 Although studies that used MDCT angiography to evaluate patients with acute chest pain reported a sensitivity of 90–100% and a specificity of 86–96%,106–110 certain limitations need to be considered. When non-diagnostic scans are taken into account, sensitivities in some of these studies may result as low as 57–77%.107,108

Overall, the diagnostic performance of CMR88–91 to detect ACS in the ED (Figure 7) is comparable to that of MDCT angiography106–111 or SPECT,103,112–118 even though comparative studies are lacking.

Congestive heart failure

Chronic heart failure in the setting of ischaemic heart disease

Patients after ACS or AMI are at increased risk for future cardiac events, and thus, ischaemia testing is reasonable to perform, for example, by utilization of perfusion-CMR or stress dobutamine-CMR or any other established ischaemia test, and ischaemia testing should be combined with a viability assessment. Since the collagen scar has relatively little intracellular space and a large interstitial space, the volume of distribution of gadolinium chelate is much higher than in the normal myocardium, resulting in a bright scar and viable myocardium appearing nulled or dark (Figures 1 and 5). In a landmark paper, Kim et al.119 demonstrated the ability of CMR to predict the recovery of segmental contractile function post-revascularization in relation to the transmurality of scar tissue in dysfunctional segments. After revascularization, segments with ≤25% transmurality of scar recovered function in about 80%, whereas <10% of segments recovered when transmurality exceeded 50% of wall thickness.119 These results were confirmed by others.68,71 Another study stressed the finding that a scar thickness of ∼4 mm or more is associated with a very low likelihood of functional recovery due to tethering, whereas a viable rim of ∼4 mm is required to allow for recovery of function.73 In addition to tissue characterization, low-dose dobutamine-CMR can be performed as well to assess the likelihood of functional recovery. Thus, patients with CHF and substantial hibernating or stunning myocardium can be readily detected by CMR and benefit from revascularization. Both scar mass120 and detection of MVO120–122 predict the outcome. In patients without MVO, MACE-free survival was ∼90% at 18 months, but decreased to ∼50% in patients with MVO. The presence of viable and scar tissue was shown to predict responsiveness to cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) using nuclear techniques.123 Novel CMR-based models propose to integrate viability data into maps of dyssynchrony to predict CRT responsiveness.124

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance is also very sensitive in detecting intracardiac thrombi that complicate infarctions in up to 20–30% of the cases.125–127 In a comparative study of 361 patients with surgical or pathological confirmation of intracardiac thrombus, CMR had a better sensitivity for thrombus detection than transoesophageal and transthoracic echocardiography while all three modalities had excellent specificities of 99, 96, and 96%, respectively.126 In another comparative study, contrast echocardiography nearly doubled sensitivity to detect LV thrombi vs. non-contrast echocardiography, but was inferior in comparison to LGE, which was particularly powerful for mural and small apical thrombi.127

Chronic heart failure in non-ischaemic heart disease

In CHF, hibernation, stunning, ischaemia, or scar is not always the substrate of dysfunction. A variety of differential diagnoses exist and CMR can considerably contribute in this situation, as the identification of different aetiologies leading to CHF is a prerequisite for a targeted CHF treatment. In dilated CMP, typically no localized endocardial scars are detected, but zones of fibrosis in the mid-wall of the interventricular septum and at the LV–RV insertion points are frequently present,128 whereas ischaemia is absent. Again, in dilative CMP, the amount of LGE is strongly related to prognosis.93 Another important differential diagnosis in CHF to consider is myocarditis. Inflammatory involvement of the myocardium is in general progressing from the subepicardial layer towards the endocardium and most frequently locates in the lateral and inferior walls of the LV.95,129–134 If inflammation results in irreversible myocyte damage, the LGE technique delineates inflammatory tissue with high spatial resolution allowing to recognize the typical pattern of lesions and also enables accurate follow-up studies to assess responsiveness to treatment. T2-weighted non-contrast- and T1-weighted contrast-enhanced CMR sequences, which are sensitive for tissue oedema, may add additional diagnostic information.135,136 Cardiac amyloidosis is another entity that can cause CHF. Conventional gadolinium-based CM exhibit a high affinity to the amyloid material, which results in specific CM kinetics. These CM kinetics can easily be assessed by the LGE technique137,138 and yield sensitivities and specificities for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis of 80 and 94%, respectively.139

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance applications are helpful in the differential diagnosis of many other cardiac diseases that can lead to CHF.5 Although many of them cannot be mentioned here, it is worthwhile to recognize that iron overload, e.g. in thalassaemia patients, is the most frequent reason causing death in this large population. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance T*2 measurements can be applied in a few breath-holds and are now generally accepted as the method of choice to guide chelation therapy as this approach could dramatically decrease the global and cardiac death rate.140,141

Safety aspects of cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Electronic devices such as pacemakers, defibrillators, infusion pumps, and others are considered as absolute contraindications.142 There is up to now one pacemaker type which obtained approval from regulatory authorities to be MR compatible, and other manufacturers will certainly follow soon with similar products. Preliminary experience shows an overall preserved image quality with this MR-compatible pacemaker with only minimal artefacts along the leads. In general, implanted devices such as heart valves, occluders, and stents143 are compatible with MR, at least up to 1.5 T (for further information, several websites are available for detailed listing).5 Claustrophobia is present in up to 5% of the cases and the administration of a tranquilizer is usually very effective.144 Concerning the administration of CM, the cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) were described where the skin and in severe cases also internal organs develop a fibrosis which can lead to death.145 This NSF is documented in some 350146–500145 cases worldwide for linear gadolinium chelates (out of up to 200 million administrations), whereas macrocyclic gadolinium chelates are considered of very low risk (with <10 unconfounded cases reported so far).

Outlook

As CMR is now entering the clinical arena, it will be crucial to monitor its performance in daily practice. Also, prognostic data on CMR are rare. The European Registry on CMR was started with a pilot in 2008 and is now active in many European countries and will deliver valuable insights regarding the prognostic yield of ischaemia and viability CMR.55,58 New CMR techniques are at the horizon in the field of metabolic imaging using hyperpolarized 13C compounds147,148 and for tissue characterization, detection of inflammation,149 and cell tracking using fluorine-based CMR.146 In the future, metabolic CMR and fluorine CMR will be fused with the ‘conventional’ function, perfusion, and viability CMR information in order to study the myocardium in depth.147,149

Conclusions

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance has developed considerably in the past years, and in particular, function, viability, and ischaemia imaging are now an integrated part of the diagnostic armamentarium in cardiology. By combining these CMR applications, CAD can be detected in its early stages and this allows for interventions with the goal to reduce complications of CAD such as infarcts and, at a later stage, heart failure. As the CMR examinations are robust and reproducible and do not expose patients to radiation, they can be repeated without harm to the patients, which is important as CAD is a chronic disease and patients therefore should be monitored over several decades.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance also progressed recently in the setting of ACS. In this situation, CMR allows for important differential diagnoses and it also delineates precisely the different tissue components in AMI such as necrosis, MVO, haemorrhage, and oedema, i.e. area at risk. With these advantages, CMR might become the preferred tool to investigate novel treatment strategies in clinical research.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charge was provided by the CMR Center of the University Hospital Lausanne (CRMC).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Fox K, Garcia M, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris. Eur Heart J. 2006 doi: 10.1157/13092800. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heart disease and stroke statistics: update 2009. Circulation. 2009;119:e1–e161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwitter J. Myocardial perfusion in ischemic heart disease. In: Higgins CB, de Roos A, editors. MRI and CT of the Cardiovascular System. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwitter J. Myocardial perfusion. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:953–963. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwitter J. CMR Update. 1st ed. Zurich: J. Schwitter; 2008. pp. 1–240. www.herz-mri.ch . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwitter J, Nanz D, Kneifel S, Bertschinger K, Buchi M, Knusel PR, Marincek B, Luscher TF, von Schulthess GK. Assessment of myocardial perfusion in coronary artery disease by magnetic resonance: a comparison with positron emission tomography and coronary angiography. Circulation. 2001;103:2230–2235. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.18.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plein S, Radjenovic A, Ridgway JP, Barmby D, Greenwood JP, Ball SG, Sivananthan MU. Coronary artery disease: myocardial perfusion MR imaging with sensitivity encoding versus conventional angiography. Radiology. 2005;235:423–430. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paetsch I, Jahnke C, Wahl A, Gebker R, Neuss M, Fleck E, Nagel E. Comparison of dobutamine stress magnetic resonance, adenosine stress magnetic resonance, and adenosine stress magnetic resonance perfusion. Circulation. 2004;110:835–842. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138927.00357.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plein S, Kozerke S, Suerder D, Luescher TF, Greenwood JP, Boesiger P, Schwitter J. High spatial resolution myocardial perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance for the detection of coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2148–2155. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwitter J, Wacker C, van Rossum A, Lombardi M, Al-Saadi N, Ahlstrom H, Dill T, Larsson HB, Flamm S, Marquardt M, Johansson L. MR-IMPACT: comparison of perfusion-cardiac magnetic resonance with single-photon emission computed tomography for the detection of coronary artery disease in a multicentre, multivendor, randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:480–489. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertschinger KM, Nanz D, Buechi M, Luescher TF, Marincek B, von Schulthess GK, Schwitter J. Magnetic resonance myocardial first-pass perfusion imaging: parameter optimization for signal response and cardiac coverage. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14:556–562. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giang T, Nanz D, Coulden R, Friedrich M, Graves M, Al-Saadi N, Lüscher T, von Schulthess G, Schwitter J. Detection of coronary artery disease by magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion imaging with various contrast medium doses: first European multicenter experience. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1657–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Saadi N, Nagel E, Gross M, Bornstedt A, Schnackenburg B, Klein C, Klimek W, Oswald H, Fleck E. Noninvasive detection of myocardial ischemia from perfusion reserve based on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2000;101:1379–1383. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagel E, Klein C, Paetsch I, Hettwer S, Schnackenburg B, Wegscheider K, Fleck E. Magnetic resonance perfusion measurements for the noninvasive detection of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2003;108:432–437. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080915.35024.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida N, Sakuma H, Motoyasu M, Okinaka T, Isaka N, Nakano T, Takeda K. Noninfarcted myocardium: correlation between dynamic first-pass contrast-enhanced myocardial MR imaging and quantitative coronary angiography. Radiology. 2003;229:209–216. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291021118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa K, Sakuma H, Nagata M, Okuda S, Hirano M, Tanimoto A, Matsusako M, Lima JA, Kuribayashi S, Takeda K. Diagnostic accuracy of stress myocardial perfusion MRI and late gadolinium-enhanced MRI for detecting flow-limiting coronary artery disease: a multicenter study. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2808–2816. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendel RC, Berman DS, Cullom SJ, Follansbee W, Heller GV, Kiat H, Groch MW, Mahmarian JJ. Multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of correction for photon attenuation and scatter in SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. Circulation. 1999;99:2742–2749. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.21.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Train KF, Garcia EV, Maddahi J, Areeda J, Cooke CD, Kiat H, Silagan G, Folks R, Friedman J, Matzer L, Germano G, Bateman T, Ziffer J, DePuey E, Fink-Bennett D, Cloninger K, Berman D. Multicenter trial validation for quantitative analysis of same-day rest-stress technetium-99m-sestamibi myocardial tomograms. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:609–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He ZX, Iskandrian AS, Gupta NC, Verani MS. Assessing coronary artery disease with dipyridamole technetium-99m-tetrofosmin SPECT: a multicenter trial. J Nuc Med. 1997;38:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaret BL, Rigo P, Wackers FJ, Hendel RC, Braat SH, Iskandrian AS, Sridhara BS, Jain D, Itti R, Serafini AN, Goris M, Lahiri A. Myocardial perfusion imaging with 99mTc tetrofosmin. Comparison to 201Tl imaging and coronary angiography in a phase III multicenter trial. Tetrofosmin International Trial Study Group. Circulation. 1995;91:313–319. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syed MA, Paterson DI, Ingkanisorn WP, Rhoads KL, Hill J, Cannon RO, 3rd, Arai AE. Reproducibility and inter-observer variability of dobutamine stress CMR in patients with severe coronary disease: implications for clinical research. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2005;7:763–768. doi: 10.1080/10976640500287414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jahnke C, Nagel E, Gebker R, Kokocinski T, Kelle S, Manka R, Fleck E, Paetsch I. Prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance stress tests: Adenosine stress perfusion and dobutamine stress wall motion imaging. Circulation. 2007;115:1769–1776. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paetsch I, Jahnke C, Ferrari VA, Rademakers FE, Pellikka PA, Hundley WG, Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Wegscheider K, Fleck E, Nagel E. Determination of interobserver variability for identifying inducible left ventricular wall motion abnormalities during dobutamine stress magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1459–1464. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plein S, Schwitter J, Suerder D, Greenwood J, Boesiger P, Kozerke S. k-t SENSE-accelerated myocardial perfusion MR imaging at 3.0 Tesla—comparison with 1.5 Tesla. Radiology. 2008;249:493–500. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492080017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner A, Bruder O, Schneider S, Nothnagel D, Buser P, Pons-Lado G, Dill T, Hombach V, Lombardi M, van Rossum A, Schwitter J, Senges J, Sabin S, Sechtem U, Mahrholdt H, Nagel E. Current variables, definitions and endpoints of the European Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Registry. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:43–55. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerqueira M, Verani M, Schwaiger M, Heo J, Iskandrian A. Safety profile of adenosine stress perfusion imaging: results from the Adenoscan Multicenter Trial Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:384–389. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belardinelli L, Linden J, Berne R. The cardiac effects of adenosine. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1989;32:73–97. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(89)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmarian JJ, Cerqueira M, Iskandrian AE, Bateman T, Thomas G, Hendel RC. Regadenoson induces comparable left ventricular perfusion defects as adenosine: a quantitative analysis from the advance MPI 2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;2:959–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagel E, Lehmkuhl HB, Bocksch W, Klein C, Vogel U, Frantz E, Ellmer A, Dreysse S, Fleck E. Noninvasive diagnosis of ischemia-induced wall motion abnormalities with the use of high-dose dobutamine stress MRI: comparison with dobutamine stress echocardiography. Circulation. 1999;99:763–770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.6.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hundley WG, Hamilton CA, Thomas MS, Herrington DM, Salido TB, Kitzman DW, Little WC, Link KM. Utility of fast cine magnetic resonance imaging and display for the detection of myocardial ischemia in patients not well suited for second harmonic stress echocardiography. Circulation. 1999;100:1697–1702. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.16.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schalla S, Klein C, Paetsch I, Lehmkuhl H, Bornstedt A, Schnackenburg B, Fleck E, Nagel E. Real-time MR image acquisition during high-dose dobutamine hydrochloride stress for detecting left ventricular wall-motion abnormalities in patients with coronary arterial disease. Radiology. 2002;224:845–851. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243010945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rerkpattanapipat P, Gandhi SK, Darty SN, Williams RT, Davis AD, Mazur W, Clark HP, Little WC, Link KM, Hamilton CA, Hundley WG. Feasibility to detect severe coronary artery stenoses with upright treadmill exercise magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jahnke C, Paetsch I, Gebker R, Bornstedt A, Fleck E, Nagel E. Accelerated 4D dobutamine stress MR imaging with k-t BLAST: feasibility and diagnostic performance. Radiology. 2006;241:718–728. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2413051522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebker R, Jahnke C, Hucko T, Manka R, Mirelis JG, Hamdan A, Schnackenburg B, Fleck E, Paetsch I. Dobutamine stress magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of coronary artery disease in women. Heart. 2010;96:616–620. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.175521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wahl A, Paetsch I, Gollesch A, Roethemeyer S, Foell D, Gebker R, Langreck H, Klein C, Fleck E, Nagel E. Safety and feasibility of high-dose dobutamine-atropine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance for diagnosis of myocardial ischaemia: experience in 1000 consecutive cases. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1230–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hundley WG, Morgan TM, Neagle CM, Hamilton CA, Rerkpattanapipat P, Link KM. Magnetic resonance imaging determination of cardiac prognosis. Circulation. 2002;106:2328–2333. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036017.46437.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davies R, Goldberg D, Forman S, Pepine C, Knatterud G, Geller N, Sopko G, Pratt C, Deanfield J, Conti C. Asymptomatic Cardiac Ischemia Pilot (ACIP) study two-year follow-up: outcomes of patients randomized to initial strategies of medical therapy versus revascularization . Circulation. 1997;95:2037–2043. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.8.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, CarloDi M, Falk V, Folliguet T, Garg S, Huber K, James S, Knuuti J, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Menicanti L, Ostojic M, Piepoli M, Pirlet C, Pomar JL, Reifart N, Ribichini F, Schalij M, Sergeant P, Serruys P, Silber S, Uva M, Taggart D. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2010 doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq1277. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diamond G, Forrester J. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ladenheim M, Pollock B, Rozanski A, Berman DS, Staniloff H, Forrester J, Diamond G. Extent and severity of myocardial hypoperfusion as predictors of prognosis in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:464–471. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico J, Friedman J, Diamond G. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1996;93:905–914. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw L, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico J, Friedman J, Diamond G. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:535–543. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iskander S, Iskandrian AE. Risk assessment using single-photon emission computed tomographic technetium-99m sestamibi imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steel K, Broderick R, Gandla V, Larose E, Resnic F, Jerosch-Herold M, Brown K, Kwong RY. Complementary prognostic values of stress myocardial perfusion and late gadolinium enhancement imaging by cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2009;120:1390–1400. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maehara A, Mintz G, Bui A, Walter O, Castagna M, Canos D, Pichard A, Satler L, Waksman R, Suddath W, Laird J, Kent K, Weissman N. Morphologic and angiographic features of coronary plaque rupture detected by intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:904–910. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burke A, Kolodgie F, Farb A, Weber D, Malcom G, Smialek J, Virmani R. Healed plaque ruptures and sudden coronary death: evidence that subclinical rupture has a role in plaque progression. Circulation. 2001;103:934–940. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ojio S, Takatsu H, Tanaka T. Considerable time from the onset of plaque rupture and/or thrombi until the onset of acute myocardial infarction in humans: coronary angiographic findings within 1 week before the onset of infarction. Circulation. 2000;102:2063–2069. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kemp H, Kronmal R, Vlietstra R, Frye R. Seven year survival of patients with normal or near normal coronary arteriograms: a CASS registry study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:479–483. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruschke AV, Kramer JR, Jr, Bal ET, Haque IU, Detrano RC, Goormastic M. The dynamics of progression of coronary atherosclerosis studied in 168 medically treated patients who underwent coronary arteriography three times. Am Heart J. 1989;117:296–305. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waters D, Lesperance J, Francetich M, Causey D, Theroux P, Chiang YK, Hudon G, Lemarbre L, Reitman M, Joyal M, Gosselin G, Dyrda I, Macer J, Havel RA. A controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of a calcium channel blocker on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1990;82:1940–1953. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Friedman J, Shaw L. Value of stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography in patients with normal resting electrocardiograms: an evaluation of incremental prognostic value and cost-effectiveness. Circulation. 2002;105:823–829. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.103973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith SJ, Feldman T, Hirshfeld JJ, Jacobs A, Kern M, King S, III, Morrison D, O'Neill W, Schaff H, Whitlow P, Williams D. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guidelines update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) Circulation. 2006;113:e166–e286. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.173220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardis E, Vrijheid M, Blettner M, Gilbert E, Hakama M, Hill C, Howe G, Kaldor J, Muirhead C, Schubauer-Berigan M, Yoshimura T, Berman F, Cowper G, Fix J, Hacker C, Heinmiller B, Marshall M, Thierry-Chef I, Utterback D, Ahn Y-O, Amoros E, Ashmore P, Auvinen A, Bae J-M, Bernar Solano J, Biau A, Combalot E, Deboodt P, Diez Sacristan A, Eklof M, Engels H, Engholm G, Gulis G, Habib R, Holan K, Hyvonen H, Kerekes A, Kurtinaitis J, Malker H, Martuzzi M, Mastauskas A, Monnet A, Moser M, Pearce M, Richardson D, Dodriguez-Artalejo F, Rogel A, Tardy H, Telle-Lamberton M, Turai I, Usel M, Veress K. Risk of cancer after low doses of ionising radiation: retrospective cohort study in 15 countries. Br Med J. 2005;331:77–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38499.599861.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Research Council; Biological effects of ionizing radiation (BEIR) reports VII-Phase 2. www.nap.edu/catalog/11340.html . [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bruder O, Schneider S, Nothnagel D, Dill T, Hombach V, Schulz-Menger J, Nagel E, Lombardi M, van Rossum A, Wagner A, Schwitter J, Senges J, Sabin G, Sechtem U, Mahrholdt H. EuroCMR (European Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filipatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ricciardi M, Wu E, Davidson C, Choi K, Klocke F, Bonow R, Judd R, Kim R. Visualization of discrete microinfarction after percutaneous coronary intervention associated with mild creatine kinase-MB elevation. Circulation. 2001;103:2780–2783. doi: 10.1161/hc2301.092121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, Holly TA, Elliott MD, Regenfus M, Parker M, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Kim RJ, Judd RM. Contrast-enhanced MRI and routine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) perfusion imaging for detection of subendocardial myocardial infarcts: an imaging study. Lancet. 2003;361:374–379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simonetti O, Kim R, Fieno D, Hillenbrand HB, Wu E, Bundy JJ, Judd R. An improved MR imaging technique for the visualization of myocardial infarction. Radiology. 2001;218:215–223. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja50215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O, Bundy J, Finn JP, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100:1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hillenbrand HB, Kim RJ, Parker MA, Fieno DS, Judd RM. Early assessment of myocardial salvage by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2000;102:1678–1683. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lima J, Judd R, Bazille A, Schulman S, Atalar E, Zerhouni E. Regional heterogeneity of human myocardial infarcts demonstrated by contrast-enhanced MRI: Potential mechanisms. Circulation. 1995;92:1117–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwitter J, Saeed M, Wendland MF, Derugin N, Canet E, Brasch RC, Higgins CB. Influence of severity of myocardial injury on distribution of macromolecules: extravascular versus intravascular gadolinium-based magnetic resonance contrast agents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rehwald WG, Fieno DS, Chen EL, Kim RJ, Judd RM. Myocardial magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent concentrations after reversible and irreversible ischemic injury. Circulation. 2002;105:224–229. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fieno D, Kim R, Chen E, Lomasney J, Klocke F, Judd R. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of myocardium at risk: distinction between reversible and irreversible injury throughout infarct healing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1985–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00958-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Judd RM, Lugo-Olivieri CH, Arai M, Kondo T, Croisille P, Lima JA, Mohan V, Becker LC, Zerhouni E. Physiological basis of myocardial contrast enhancement in fast magnetic resonance images of 2-day-old reperfused canine infarcts. Circulation. 1995;92:1902–1910. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rochitte CE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Reeder SB, McVeigh ER, Furuta T, Becker LC, Melin JA. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;98:1006–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beek AM, Kuhl HP, Bondarenko O, Twisk JW, Hofman MB, van Dockum WG, Visser CA, van Rossum AC. Delayed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for the prediction of regional functional improvement after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:895–901. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00835-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi KM, Kim RJ, Gubernikoff G, Vargas JD, Parker M, Judd RM. Transmural extent of acute myocardial infarction predicts long-term improvement in contractile function. Circulation. 2001;104:1101–1107. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.096798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ingkanisorn W, Rhoads K, Aletras A, Kellman P, Arai A. Gadolinium delayed enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance correlates with clinical measures of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2253–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gutberlet M, Frohlich M, Mehl S, Amthauer H, Hausmann H, Meyer R, Siniawski H, Ruf J, Plotkin M, Denecke T, Schnackenburg B, Hetzer R, Felix R. Myocardial viability assessment in patients with highly impaired left ventricular function: comparison of delayed enhancement, dobutamine stress MRI, end-diastolic wall thickness, and TI201-SPECT with functional recovery after revascularization. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:872–880. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2653-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klein C, Nekolla SG, Bengel FM, Momose M, Sammer A, Haas F, Schnackenburg B, Delius W, Mudra H, Wolfram D, Schwaiger M. Assessment of myocardial viability with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:162–167. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Knuesel PR, Nanz D, Wyss C, Buechi M, Kaufmann PA, von Schulthess GK, Luscher TF, Schwitter J. Characterization of dysfunctional myocardium by positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance: relation to functional outcome after revascularization. Circulation. 2003;108:1095–1100. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085993.93936.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuhl H, Beek A, van der Weerdt A, Hofman M, Visser C, Lammertsma A, Heussen N, Visser F, van Rossum A. Myocardial viability in chronic ischemic heart disease: comparison of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomograph. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim RJ, Albert T, Wible J, Elliott MD, Allen JM, Lee J, Parker M, Napoli A, Judd R. Performance of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging with gadoversetamide contrast for the detection and assessment of myocardial infarction: an international, multicenter, double-blinded, randomized trial. Circulation. 2008;117:629–637. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Atar D, Petzelbauer P, Schwitter J, Huber K, Rensing B, Kasprzak J, Butter C, Grip L, Hansen P, Süselbeck T, Clemmensen P, Marin-Galiano M, Geudelin B, Buser P Investigators ftF. Effect of intravenous FX06 as an adjunct to primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aletras A, Tilak G, Natanzon A, Hsu L-Y, Gonzalez F, Hoyt RJ, Arai A. Retrospective determination of the area at risk for reperfused acute myocardial infarction with T2-weighted cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: histopathological and displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) functional validations. Circulation. 2006;113:1865–1870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.576025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giri S, Chung Y, Merchant A, Mihai G, Rajagopalan S, Raman S, Simonetti O. T2 quantification for improved detection of myocardial edema. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Francone M, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Carbone I, Canali E, Scardala R, Calabrese F, Sardella G, Mancone M, Catalano C, Fedele F, Passariello R, Bogaert J, Agati L. Impact of primary coronary angioplasty delay on myocardial salvage, infarct size, and microvascular damage in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2145–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eitel I, Desch S, Fuernau G, Hildebrand L, Gutberlet M, Schuler G, Thiele H. Prognostic significance and determinants of myocardial salvage assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute reperfused myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2470–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lotan C, Bouchard A, Cranney G, Bishop S, Pohost G. Assessment of postreperfusion myocardial hemorrhage using proton NMR imaging at 1.5 T. Circulation. 1992;86:1918–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Basso C, Corbetti F, Silva C, Abudureheman A, Lacognata C, Cacciavillani L, Tarantini G, Marra M, Ramondo A, Thiene G, Iliceto S. Morphologic validation of reperfused hemorrhagic myocardial infarction by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1322–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O'Regan D, Ahmed R, Karunanithy N, Neuwirth C, Tan Y, Durighel G, Hajnal J, Nadra I, Corbett S, Cook S. Reperfusion hemorrhage following acute myocardial infarction: assessment with T2* mapping and effect on measuring the area at risk. Radiology. 2009;250:916–922. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503081154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ganame J, Messalli G, Dymarkowski S, Rademakers FE, Desmet W, Van de Werf F, Bogaert J. Impact of myocardial haemorrhage on left ventricular function and remodelling in patients with reperfused acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1440–1449. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Forest R, Shofer F, Sease K, Hollander J. Assessment of the standardized reporting guidelines ECG classification system: the presenting ECG predicts 30-day outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gibler W, Cannon C, Blomkalns A, Char D, Drew B, Hollander J, Jaffe A, Jesse R, Newby L, Ohman E, Peterson ED, Pollak C. Practical implementation of the guidelines for unstable angina/non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in the emergency department. Circulation. 2005;111:2699–2710. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165556.44271.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bassand J-P, Hamm C, Ardissino D, Boersma E, Budaj A, Fernandez-Aviles F, Fox K, Hasdai D, Ohman E, Wallentin L, Wijns W. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1598–1660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kwong R, Schussheim A, Rekhraj S, Aletras A, Geller NL, Davis J, Christian T, Balaban R, Arai A. Detecting acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;107:531–537. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047527.11221.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cury R, Shash K, Nagurney J, Rosito G, Shapiro M, Nomura C, Abbara S, Bamberg F, Ferencik M, Schmidt E, Brown D, Hoffmann U, Brady T. Cardiac magnetic resonance with T2-weighted imaging improves detection of patients with acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department. Circulation. 2008;118:837–844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ingkanisorn WP, Kwong RY, Bohme NS, Geller NL, Rhoads KL, Dyke CK, Paterson DI, Syed MA, Aletras AH, Arai AE. Prognosis of negative adenosine stress magnetic resonance in patients presenting to an emergency department with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1427–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Plein S, Greenwood J, Ridgeway J, Cranny G, Ball SG, Sivananthan M. Assessment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2173–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miller C, Hwang W, Hoekstra J, Case D, Lefebvre C, Blumstein H, Hiestand B, Diercks D, Hamilton CA, Harper E, Hundley WG. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with observation unit care reduces cost for patients with emergent chest pain: a randomized trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Assomull R, Prasad S, Lyne J, Smith G, Burman E, Khan M, Sheppard M, Poole-Wilson P, Pennell D. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;48:1977–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Laissy JP, Hyafil F, Feldman LJ, Juliard JM, Schouman-Claeys E, Steg PG, Faraggi M. Differentiating acute myocardial infarction from myocarditis: diagnostic value of early- and delayed-perfusion cardiac MR imaging. Radiology. 2005;237:75–82. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Deluigi CC, Kispert E, Hager S, Meinhardt G, Vogelsberg H, Fritz P, Dippon J, Bock CT, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Sechtem U. Presentation, patterns of myocardial damage, and clinical course of viral myocarditis. Circulation. 2006;114:1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Haghi D, Fluechter S, Suselbeck T, Kaden J, Borggrefe M, Papavassiliu T. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in typical versus atypical forms of the acute apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) Int J Cardiol. 2007;120:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mitchell J, Hadden T, Wilson J, Achari A, Muthupillai R, Flamm S. Clinical features and usefulness of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in assessing myocardial viability and prognosis in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome) Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rolf A, Nef H, Moellmann H, Troidl C, Voss S, Conradi G, Rixe J, Steiger H, Beiring K, Hamm C, Dill T. Immunohistological basis of the late gadolinium enhancement phenomenon in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1635–1642. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eitel I, Lucke C, Grothoff M, Sareban M, Schuler G, Thiele H, Gutberlet M. Inflammation in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:422–431. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schwitter J. MRI and MRA of the thoracic aorta. Appl Radiol. 2006;Suppl. May:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Levitt M, Promes S, Bullock S, Disano M, Young G, Gee G, Peaslee D. Combined cardiac marker approach with adjunct two-dimensional echocardiography to diagnose acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kontos M, Arrowood J, Paulsen W, Nixon J. Early echocardiography can predict cardiac events in emergency department patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:550–557. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaul S, Senior R, Firschke C, Wang X, Lindner J, Villanueva F, Firozan S, Kontos M, Taylor AJ, Nixon I, Watson D, Harrell F. Incremental value of cardiac imaging in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain and without ST-segment elevation: a multicenter study. Am Heart J. 2004;148:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Udelson J, Beshansky J, Ballin D, Feldman J, Griffith J, Heller GV, Hendel RC, Pope J, Ruthazer R, Spiegler E, Woolard R, Handler J, Selker H. Myocardial perfusion imaging for evaluation and triage of patients with suspected acute cardiac ischemia. JAMA. 2002;288:2693–2700. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]