Abstract

Inhibition of large conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels mediates, in part, oxygen sensing by carotid body type I cells. However, BKCa channels remain active in cells that do not serve to monitor oxygen supply. Using a novel, bacterially derived AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), we show that AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits BKCa channels in a splice variant-specific manner. Inclusion of the stress-regulated exon within BKCa channel α subunits increased the stoichiometry of phosphorylation by AMPK when compared with channels lacking this exon. Surprisingly, however, the increased phosphorylation conferred by the stress-regulated exon abolished BKCa channel inhibition by AMPK. Point mutation of a single serine (Ser-657) within this exon reduced channel phosphorylation and restored channel inhibition by AMPK. Significantly, RT-PCR showed that rat carotid body type I cells express only the variant of BKCa that lacks the stress-regulated exon, and intracellular dialysis of bacterially expressed AMPK markedly attenuated BKCa currents in these cells. Conditional regulation of BKCa channel splice variants by AMPK may therefore determine the response of carotid body type I cells to hypoxia.

Keywords: AMP-activated Kinase (AMPK), Hypoxia, Ion Channels, Phosphorylation Enzymes, Signal Transduction, BKCa, Carotid Body, Type I Cell

Introduction

Upon exposure to hypoxia, carotid body type I cells depolarize, precipitating voltage-gated Ca2+ influx and neurosecretion, which leads to increased sensory afferent discharge to the brain stem and, ultimately, corrective changes in breathing (1, 2). It is well established that this process is mainly driven by inhibition of discrete populations of oxygen-sensitive K+ channels, and we have recently proposed that hypoxia-response coupling in carotid body type I cells is mediated, at least in part, by the metabolic sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)3 (3, 4).

AMPK exists as heterotrimers comprising catalytic α subunits and regulatory β and γ subunits (5). It is only active after phosphorylation of Thr-172 on the α subunit by upstream kinases, which include the tumor suppressor, LKB1 (6). Activation occurs in response to cellular stresses that either accelerate ATP consumption or inhibit ATP production, which increase the ADP/ATP ratio and, via the action of adenylate kinases, AMP/ATP. This leads to exchange of AMP for ATP at two sites on the AMPK γ subunit (7), triggering allosteric activation (8) and inhibition of Thr-172 dephosphorylation (9). AMPK can also be activated by CaMKKβ in response to increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ (10, 11). Once activated, AMPK phosphorylates downstream targets that activate ATP-generating catabolic pathways while switching off ATP-consuming processes. Most targets identified to date are proteins directly involved in metabolism, cell growth or the cell cycle, or proteins that affect the expression of genes involved in those processes (5).

Consistent with our proposal that AMPK mediates hypoxia-response coupling, we recently showed that AMPK activation, like hypoxia, selectively inhibits oxygen-sensitive K+ currents in carotid body type I cells, including the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, BKCa (3). We also showed that the addition of AMPK activators to HEK293 cells stably expressing the pore-forming BKCa α subunits inhibited macroscopic channel currents, and that purified AMPK phosphorylated BKCa α subunits immunopurified from the cells. However, both AMPK (5) and BKCa channels (12) are widely expressed in mammalian cells, many of which do not function to monitor oxygen supply.

Functional heterogeneity in BKCa channel properties, including divergent regulation by the same signaling pathway, may be conferred through alternate splicing of pre-mRNA derived from the single gene encoding the α subunit (Kcnma1). Thus, previous studies have shown that regulation of BKCa channels by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) is determined by the α subunit splice variant (13, 14) because PKA has been shown to activate homotetramers containing the ZERO variant that lacks the “stress-regulated exon” (STREX) and inhibit homotetramers of variants containing the STREX exon. As pre-mRNA splicing is tissue-specific and developmentally regulated (15–17), alternative splicing has also been suggested as an attractive mechanism to explain tissue-specific regulation of BKCa channels by hypoxia (18).

We therefore considered the possibility that AMPK might differentially regulate BKCa channel splice variants and in a manner that may confer tissue-specific regulation of BKCa channels by hypoxia. To this end, we studied AMPK-dependent phosphorylation and regulation of the ZERO and STREX variants of the BKCa channel α subunits expressed in HEK293 cells and the regulation by AMPK of endogenous BKCa channels in carotid body type I cells. Using a novel thiophosphorylated, phosphatase-resistant form of the AMPK heterotrimer, we provide evidence that alternate splicing of mRNA encoding the BKCa α subunits profoundly affects the regulation of the channel by AMPK. Thus, although both the ZERO and STREX variants were phosphorylated by AMPK, only K+ currents carried by the ZERO variant were inhibited. Moreover, we demonstrate that the “AMPK-sensitive” ZERO variant, but not the “AMPK-insensitive” STREX variant, is expressed in the oxygen-sensitive carotid body type I cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Isolation

HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic solution.

Carotid Body Type I Cells

Neonatal rats (10 days) were terminally anesthetized, and carotid bodies were rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline without Ca2+ or Mg2+ (Sigma). These were then enzymically dissociated and cultured as described previously (19).

Cell Transfection

Murine BKCa channel α subunit splice variants (ZERO and STREX) encoded by the murine Kcnma1 gene (GenBankTM accession number AF156674) were cloned with a C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag (14). Site-directed mutagenesis created an S657A mutation within the STREX insert, with the mutation confirmed by DNA sequencing. Cells were transfected with 12 μg of DNA using Fugene 6 (Roche Applied Science) for protein phosphorylation assays or with 1.5 μg of DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for electrophysiological assays, following the manufacturer's instructions.

Purification and Activation of Rat Liver AMPK and Bacterially Expressed AMPK

A GST fusion of CAMKKβ was expressed and purified as described (10). Rat liver AMPK was purified as described previously (21). A polycistronic plasmid expressing His6-tagged human AMPK (α2β2γ1 complex, a gift from AstraZeneca) was purified using a HIS trap column (GE Healthcare) and eluted using an imidazole gradient. The fractions containing AMPK were pooled and dialyzed against 50 mm NaHepes, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol. Adenosine ATPγS and other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Bacterially expressed human AMPK was incubated with CaMKKβ with ATP or ATPγS (200 μm) plus MgCl2 (5 mm) at 30 °C. Aliquots were removed at intervals, and the reaction was stopped by incubation with excess EDTA. Kinase activity was determined using the SAMS peptide assay as described previously (22), after the addition of excess Mg2+. To assess dephosphorylation, kinase phosphorylated in the presence of either ATP or ATPγS was incubated with bacterially expressed protein phosphatase-1γ (PP1γ) sufficient to give complete dephosphorylation of the enzyme phosphorylated using ATP in 30 min. Aliquots were removed at intervals, incubated with okadaic acid (8 μm) to inhibit the phosphatase, and assayed for AMPK as before. When preparing thiophosphorylated kinase for electrophysiology studies, AMPK was incubated with CaMKKβ for 30 min at 30 °C, CaMKKβ was removed by adsorption on GST-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), and the active AMPK complex was dialyzed against 50 mm NaHepes, pH 8.0, 140 mm KCl.

Phosphorylation Assays

Buffers for lysis and purification were from the μMACS epitope tag protein isolation kit (Miltenyl Biotec). 36–48 h post-transfection, cells plated on a 10-cm culture dish were lysed in 400 μl of lysis buffer (supplied by Miltenyl Biotec) supplemented with protease inhibitor tablets (Roche Applied Science) and 1 mm dithiothreitol. After lysis, cells were left on ice for 30 min and harvested at 10,000 × g/min for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and incubated with 35 μl of HA-tagged magnetic beads for 30 min at 4 °C. During the incubation, a μColumn was placed in the magnetic field of the μMACS separator and equilibrated with 200 μl of lysis buffer. Cell lysate was then applied to the column, followed by 4 × 200 μl of wash buffer 1, 1 × 100 μl of wash buffer 2 (buffers supplied by Miltenyl Biotec), and 4 × 200 μl of wash buffer 3 (50 mm NaHepes, pH 7.4, 1 mm dithiothreitol). The channel was dephosphorylated by incubation of PP1γ for 30 min at 30 °C, after which the column was washed with 4 × 200 μl of wash buffer 3 supplemented with 1 m NaCl, followed by 4 × 200 μl of wash buffer 3. The protein was then incubated with 5 mm MgCl2, 200 μm [γ-32P]ATP, 8 μm okadaic acid, with or without bacterially expressed α2β2γ1 (10 units/ml; activated using CaMKKβ and ATP as above) or AMPK purified from rat liver (5 units/ml) in the presence or absence of 200 μm AMP for 30 min at 30 °C. The column was then washed in 4 × 200 μl of wash buffer 3 supplemented with 1 m NaCl and 4 × 200 μl of wash buffer 3. Protein was eluted from the column by incubation with 20 μl of preheated elution buffer (Miltenyl Biotec) for 5 min, followed by elution with 50 μl of preheated elution buffer. Proteins were analyzed on SDS-PAGE using the 4–12% gradient BisTris system (Invitrogen). Incorporation of phosphorylation was determined as described previously (3).

Electrophysiology

Cells were plated onto coverslips and transferred to a recording chamber mounted on the stage of an Olympus CK40 or a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope. All experiments were carried out at 37 ± 1 °C unless otherwise stated. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were obtained in voltage clamp mode using patch pipettes of 4–7-megaohm resistance.

Recordings from HEK293 cells, transiently transfected with BKCa splice variants and mutants, were obtained using pipettes filled with an intracellular solution of the following composition (pH 7.2): 140 mm KCl, 1 mm BAPTA, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm MgATP, 0.3 mm NaGTP. The calculated free Ca2+ concentration for this solution was 0.5 μm. Cells were bathed in a physiological salt solution of the following composition (pH 7.4): 135 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm d-glucose, 10 mm HEPES.

Recordings from the type I cells were obtained using pipettes filled with an intracellular solution of the following composition (pH 7.2): 10 mm NaCl, 117 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 11 mm HEPES, 11 mm EGTA, 1 mm CaCl2, 2 mm Na2ATP. Cells were continuously superfused (3–5 ml/min) with a physiological salt solution that was constantly bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2 and had the following composition (pH 7.4): 117 mm NaCl, 4.5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 23 mm NaHCO3, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 11 mm d-glucose. To identify the contribution of BKCa channels to the total outward K+ current, BKCa channels were inhibited by switching the superfusate to a “high Mg2+” perfusate in which 6 mm MgCl2 and 0.1 mm CaCl2 was substituted for 1 mm MgCl2 and 2 mm CaCl2 (23).

Series resistance was monitored after breaking into the whole-cell configuration throughout the duration of experiments. If a significant increase (>20%) occurred, the experiment was terminated. Signals were acquired using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc.) controlled by Clampex version 9.0 or 10 software via a Digidata 1322A interface (Axon Instruments, Inc.). Data were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. To evoke ionic currents, a step depolarization was applied from −70 mV to +60 or +100 mV. Offline analysis was carried out using Clampfit version 9 or 10 (Axon Instruments, Inc.).

RT-PCR

Whole Carotid Body

Carotid bodies were removed from P10 rats and placed in RNAlater® Tissue Collection: RNA Stabilization Solution (Ambion). RNA was extracted using the RNeasy microkit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's guidelines, and concentration was determined using the Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific). cDNA synthesis was carried out using the Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science) following the manufacturer's instructions.

For PCR analysis, 5 μl of cDNA was used in a 50-μl reaction using GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega) and the following primers: BKCa channel α subunit (which spanned the site of splicing C2 to detect BKCa channel splice variants), forward (5′-gTTTgTgAgCTgTgTTTTgTg) and reverse (5′-gTgTTTgAgCTCATgATAgTg). To demonstrate that cDNA was, at least in part, derived from carotid body type I cells in whole carotid body extracts, primers for tyrosine hydroxylase were also used for PCR analysis: forward (5′-TCCTCCTTgTCTCgggCTgTAAAAg) and reverse (5′-CTTgggAACCAggggACCTTgTC).

Single Type I Cells

The cellular contents of single, isolated carotid body type I cells were aspirated into RNase-free borosilicate patch pipettes containing 7 μl of RNase-free water. Aspirant was immediately transferred to a microcentrifuge tube for cDNA synthesis using Sensiscript® reverse transcriptase (Qiagen), RNasin® ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega) and a mix of random and poly(dT) primers in a final volume of 20 μl at 37 °C for 1 h. For PCR analysis, 2–5 μl of single cell cDNA was used in a 20-μl reaction using GoTaq® DNA polymerase (Promega) using the same primers as above.

Amplification of single cell cDNA isolated from different individual cells was run in parallel with multiple negative controls using an initial denaturing step at 94 °C for 5 min and then denaturing at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 45 s, and extension for 60 s at 72 °C using 35–40 cycles with a final 7-min extension at 72 °C. Negative controls included control cell aspirants, for which no reverse transcriptase was added, and aspiration of extracellular medium and PCR controls. None of the controls produced any detectable amplicon, ruling out genomic or other contamination. Amplicons were run on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized using SYBRSafeTM (Invitrogen).

Data Analysis

Significance of differences in phosphorylation stoichiometry with the ZERO, STREX, and S657A mutant STREX variants was determined by one-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Effects of AMPK (pharmacological activation or application of heterotrimers) were analyzed by paired or unpaired Student's t tests, as indicated.

RESULTS

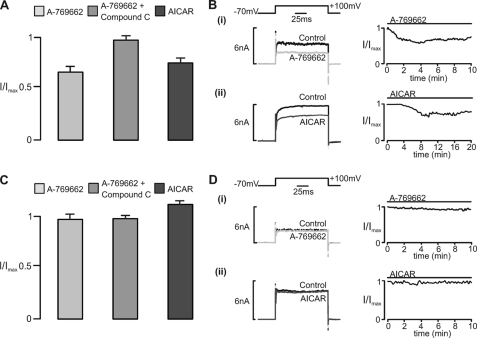

The ZERO and STREX variants of BKCa were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, and outward K+ channel currents were recorded in the whole-cell configuration under voltage clamp by applying a voltage step from a holding potential of −70 mV to +100 mV. We then assessed the effect on evoked current amplitude of extracellular application of two structurally unrelated AMPK activators with different mechanisms of action: 1) A-769662 (100 μm), which activates AMPK by directly binding to the β1 subunit at a site distinct from the AMP binding sites (24, 25); 2) 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside (AICAR; 1 mm), a nucleoside that is taken up into cells and then metabolized to the AMP mimetic, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-b-d-ribofuranosyl, thus activating AMPK (8). Fig. 1A shows the effects of A-769662 and AICAR in cells transfected with the ZERO variant of BKCa. Inhibition of the current carried by the ZERO variant was clearly observed after extracellular application of A-769662 in the absence but not in the presence of 40 μm compound C, an AMPK antagonist that may also inhibit other kinases (26). Consistent with our earlier study (3), extracellular application of AICAR too inhibited the ZERO variant, an effect we have previously shown to be blocked by compound C (3). In marked contrast, in cells transfected with the STREX variant (Fig. 1B), the current amplitude remained stable during extracellular application (≥10 min) of either A-769662 or AICAR and throughout the current-voltage range (data not shown). Although both A-769662 and AICAR have been shown to have AMPK-independent effects, none have been common to both agents. Moreover, the fact that inhibition of the ZERO variant of BKCa by each AMPK agonist was abolished by an AMPK antagonist, compound C, provides further support for the view that both agents mediate inhibition of the ZERO variant of the BKCa channel α subunit through AMPK activation rather than by any other mechanism. That this is the case gained further support from studies using a recombinant human α2β2γ1 heterotrimer (see below).

FIGURE 1.

AMPK-dependent regulation of whole-cell currents carried by BKCa splice variants expressed in HEK293 cells. A, bar chart shows the residual whole-cell K+ current (I/Imax; mean ± S.E.) carried by the ZERO splice variant of BKCa after extracellular application of the AMPK agonist A-769662 (100 μm) in the absence and presence of compound C (40 μm) and after extracellular application of AICAR (1 mm). For A-769662, residual current measured 0.68 ± 0.04 of control (p < 0.01) after 6 ± 0.2 min (n = 4) in the absence and 0.94 ± 0.06 (n = 3) after 10 min in the presence of compound C. For AICAR, residual current measured 0.72 ± 0.08 of control (p < 0.01) after 10 ± 0.5 min (n = 4). B, examples of the whole-cell K+ currents recorded (left panels) and plots of current magnitude against time (right panels) before and after extracellular application of A-769662 (100 μm) and AICAR (1 mm). C and D, as in A and B but for the STREX splice variant. For A-769662 (i), residual current measured 0.97 ± 0.07 (n = 5) after 10 min in the absence and 0.96 ± 0.06 (n = 3) in the presence of compound C. For AICAR (ii), residual current measured 1.12 ± 0.15 (n = 3) after 10 min.

Given that AMPK activation by A-769662 and AICAR was without effect on K+ currents carried by the STREX variant, we next assessed the impact of the presence of the STREX insert on phosphorylation of BKCa by AMPK. We first assessed the phosphorylation of BKCa channel α subunit splice variants by AMPK purified from rat liver extract (a mixture of the α1β1γ1 and α2β1γ1 heterotrimers). The STREX or ZERO variants of BKCa immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells were incubated with rat AMPK and [γ-32P]ATP in the presence and absence of AMP. Fig. 2, A and B, shows that rat liver AMPK phosphorylated both variants and that this was dependent on the addition of AMPK and was markedly stimulated by AMP. Fig. 2C shows immunoprecipitates of ZERO and STREX variants incubated with [γ-32P]ATP and bacterially expressed human α2β2γ1 heterotrimer that had been activated by incubation with CaMKKβ and ATP (note the slightly more rapid migration of the smaller ZERO variant). The recombinant human AMPK heterotrimer phosphorylated both variants, but the stoichiometry of phosphorylation was significantly higher with the STREX variant, increasing from 0.96 ± 0.09 mol/mol (n = 6) for ZERO to 1.51 ± 0.07 mol/mol for the STREX variant (mean ± S.D., n = 5, p < 0.001 by one-way analysis of variance). The STREX insert contains a serine (Ser-657 in the full sequence, underlined below) with a surrounding sequence (RSERDCSCMSG) that is a partial fit to the consensus recognition motif for AMPK (27). This serine is preceded by the expected arginine residues at P−3 and P−6, although bulky hydrophobic residues (rather than the serine and glycine found at this site) are usually preferred at positions P−5 and P+4. Despite this, Fig. 2D shows that a serine to alanine mutation (S657A) significantly attenuated phosphorylation of the STREX variant, reducing the stoichiometry of phosphorylation from 1.51 ± 0.07 (n = 5) to 1.14 ± 0.02 (n = 3) mol/mol (p < 0.001) (i.e. to a value similar to that observed with the ZERO variant) (Fig. 2C). Thus, although the ZERO and STREX variants are both phosphorylated by AMPK, there may be an additional phosphorylation site in the STREX variant (possibly Ser-657 within the STREX insert itself).

FIGURE 2.

AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of BKCa splice variants. Autoradiogram (32P) and Coomassie Blue-stained gel and autoradiogram demonstrating phosphorylation of the STREX (A) and ZERO (B) splice variants of BKCa by AMPK purified from rat liver extract in the presence and absence of 200 μm AMP. C, autoradiogram and Coomassie Blue-stained gel demonstrating phosphorylation of the ZERO and STREX variants by human AMPK (α2β2γ1; 10 units/ml), showing the greater degree of phosphorylation of the STREX variant. D, autoradiogram and Coomassie Blue-stained gel demonstrating phosphorylation of the STREX variant and the S657A STREX mutant by human AMPK (α2β2γ1; 10 units/ml), showing the lower degree of phosphorylation of the S657A mutant. Note that for observations analyzed on a fixed percentage acrylamide protein gel, STREX and ZERO protein migrated at 137 and 131 kDa, respectively. In contrast, when analyzed on a 4–12% BisTris precast gel (Invitrogen), the STREX and ZERO proteins migrated with a smaller apparent mass of 97 and 90 kDa, respectively.

We next wished to examine the effect of introducing recombinant AMPK by intracellular dialysis on BKCa channel function in intact cells. Because it was likely that cellular phosphatases would dephosphorylate Thr-172, causing inactivation of the kinase, we purified dephosphorylated and inactive recombinant human α2β2γ1 heterotrimers from bacterial extracts and activated them using CaMKKβ and ATPγS. This yields complexes with thiophosphate rather than phosphate at Thr-172 on the α subunit; it has been previously shown that thiophosphate groups are resistant to dephosphorylation (28). Fig. 3A shows that the wild type α2β2γ1 complexes could be activated by CaMKKβ using either ATP or ATPγS, although the amount of activation obtained using ATPγS was about half that obtained with ATP. However, although the complex phosphorylated using ATP was rapidly inactivated by incubation with recombinant PP1γ, the monothiophosphorylated complex was completely resistant to PP1γ treatment (Fig. 3B). We also confirmed the rapid phosphorylation of Thr-172 with ATP and CaMKKβ and its subsequent dephosphorylation using PP1γ by Western blotting using a phosphospecific antibody (not shown), but the thiophosphorylated protein was not be detected using this antibody.

FIGURE 3.

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of AMPK using ATP or ATPγS. A, activation of human AMPK (α2β2γ1) by CaMKKβ using ATP (open circles) or ATPγS (filled circles). B, activity of AMPK that had been phosphorylated using ATP or ATPγS (as in A) during subsequent incubation with PP1γ.

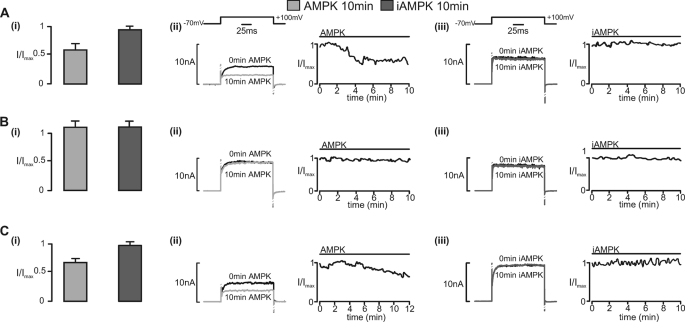

Fig. 4A shows the effects of thiophosphorylated active AMPK and inactive, thiophosphorylated control (D157A mutant, designated iAMPK) on the ZERO variant of BKCa. Current inhibition was clearly observed during intracellular dialysis with active but not inactive AMPK. By contrast, Fig. 4B shows that in cells expressing the STREX variant, BKCa current amplitude remained stable for up to 10 min of intracellular dialysis with either active or inactive AMPK.

FIGURE 4.

Regulation by recombinant AMPK heterotrimers of whole-cell currents carried by BKCa splice variants expressed in HEK293 cells. Bar charts show the residual whole-cell K+ current (I/Imax; mean ± S.E. (error bars)) carried by the ZERO (A (i)) and STREX (B (i)) splice variants of BKCa and by the S657A mutant (C (i)) after intracellular dialysis (10 min) of a constitutively active AMPK heterotrimer (AMPK; bacterially derived thiophosphorylated α2β2γ1) or an inactive AMPK heterotrimer (iAMPK; bacterially derived kinase-dead α2β2γ1). For the ZERO variant, residual current measured 0.60 ± 0.07 of control (p < 0.01) after 5 ± 0.4 min (n = 8) with AMPK and 0.96 ± 0.08 (n = 3) after 10 min with iAMPK. For the STREX variant, residual current measured 1.17 ± 0.14 (n = 4) of control with AMPK and 1.15 ± 0.1 (n = 3) after 10 min with iAMPK. For the S657A mutant, residual current measured 0.68 ± 0.06 (n = 4) of control (p < 0.01) with AMPK and 0.91 ± 0.08 (n = 3) with iAMPK after 10 min. A–C (ii and iii) show examples of the whole-cell K+ currents recorded after 0 and 10 min (left) and plots of current magnitude against time following intracellular dialysis of AMPK and iAMPK, respectively, to each of the aforementioned BKCa variants (right).

Strikingly, inhibition of BKCa was restored in the STREX variant by a serine to alanine mutation (S657A) within the STREX insert, so that the results with the S657A mutant were similar to those obtained with the ZERO variant. Thus, progressive current inhibition was observed after extracellular application of A-769662 (0.68 ± 0.06 after 5 ± 0.2 min; n = 6) or intracellular dialysis of thiophosphorylated AMPK but not iAMPK (Fig. 4C). Therefore, AMPK inhibits the ZERO but not the STREX variant of the BKCa α subunit, with this switch determined by the likely phosphorylation of a single conserved serine residue, Ser-657, within the STREX insert.

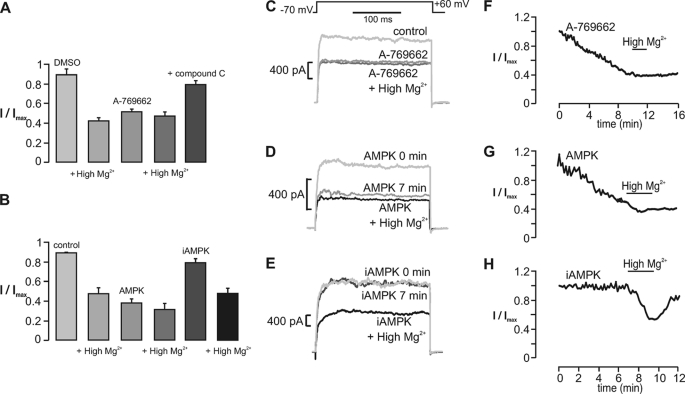

We next sought to determine the effect of recombinant AMPK on BKCa channel currents in acutely isolated carotid body type I cells. Outward K+ currents were activated in rat carotid body type I cells by a voltage step to +60 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV before and during extracellular application of A-769662 or intracellular dialysis of the thiophosphorylated α2β2γ1 heterotrimer or the inactive mutant. In each case, the perfusate was switched to one containing high Mg2+ (6 mm) and low Ca2+ (0.1 mm; termed “high Mg2+”) to provide for selective block by Mg2+/low Ca2+ of BKCa channels in type I cells (23). Thereby, the specific contribution of BKCa channels to the measured outward current in type I cells was assessed relative to, for example, the delayed rectifier potassium current.

As summarized in Fig. 5A, the switch to high Mg2+ reduced outward K+ currents in type I cells, in agreement with previous studies (23). Exposure of cells to A-769662 caused progressive inhibition of currents that peaked after 10 min and was blocked by the non-selective AMPK antagonist, compound C. Furthermore, subsequent switching to the high Mg2+ solution caused no further inhibition (Fig. 5, C and F). These results are consistent with our previous finding (3, 29) that pharmacological activation of AMPK with AICAR leads to inhibition of BKCa channels without affecting other voltage-gated K+ currents in type I carotid body cells. Fig. 5B shows that, when compared with time-matched controls (containing no heterotrimer), current inhibition was caused by active AMPK but not iAMPK, reaching a plateau at 8 min (p < 0.01; Fig. 5B). As was seen with application of A-769662, currents observed in cells dialyzed with the active heterotrimer were not reduced further following the switch to perfusate containing high Mg2+, indicating that the heterotrimer had caused selective inhibition of BKCa channels in type I cells (Fig. 5, D and G). By contrast, dialysis with inactive AMPK was without significant effect on current amplitudes, and the switch to high Mg2+ led to significant current inhibition, comparable with that seen in cells dialyzed without added heterotrimers (Fig. 5, B, E, and H). These data provide both molecular and pharmacological evidence that AMPK selectively inhibits BKCa channels, rather than other voltage-gated K+ currents, in rat carotid body type I cells.

FIGURE 5.

AMPK-dependent regulation of the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ current in carotid body type I cells. A, bar chart shows the residual whole-cell K+ current (I/Imax; mean ± S.E. (error bars)) recorded under control (1:1000 DMSO) conditions and after a 15-min incubation with the AMPK agonist A-769662 (100 μm) both in the absence and presence of high Mg2+ and in the presence of A-769662 and compound C (40 μm). Upon switching to high Mg2+, residual outward current (I/Imax; mean ± S.E.) measured 0.48 ± 0.04 (p < 0.01; n = 7) from 0.92 ± 0.03. Residual current measured 0.53 ± 0.04 (p < 0.01; n = 7) after 10.28 ± 0.89 min with A-769662 (high Mg2+ = 0.43 ± 0.03; n = 6) and 0.81 ± 0.04 (n = 7) with A-769662 and compound C. B, bar chart shows the residual whole-cell K+ current (I/Imax; mean ± S.E.) recorded under control conditions and 13 min after intracellular dialysis of a constitutively active AMPK heterotrimer (AMPK; bacterially derived and thiophosphorylated α2β2γ1) or inactive AMPK heterotrimer (iAMPK; bacterially derived kinase-dead α2β2γ1) both in the absence and presence of high Mg2+. Residual current measured 0.37 ± 0.04 (p < 0.01; n = 6) after 7.53 ± 0.54 min with AMPK (high Mg2+ = 0.31 ± 0.05; p < 0.01; n = 6) and 0.79 ± 0.04 (n = 6) after 10 min with iAMPK (high Mg2+ = 0.48 ± 0.04; p < 0.01; n = 6). The middle panels show example records of whole-cell K+ current recorded before and after equilibration with A-769662 (C), AMPK (D), and iAMPK (E). The right-hand panels show the time course for inhibition of whole-cell K+ current during extracellular application of A-769662 (F) and intracellular dialysis of AMPK (G) and iAMPK (H).

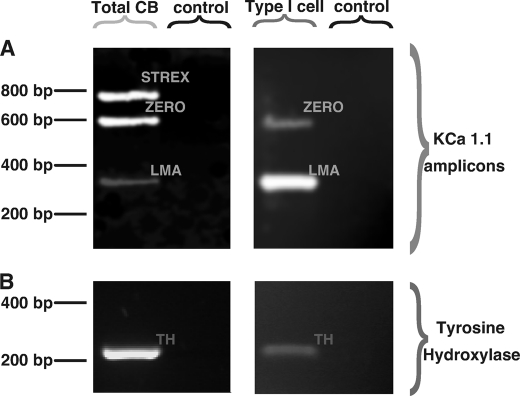

Fig. 6A shows that RT-PCR products from mRNA that was extracted from whole rat carotid bodies (Total CB) corresponding to 1) identified amplicons for both the ZERO and STREX splice variants of the BKCa α subunit and 2) an as yet unidentified low molecular weight amplicon (LMA) of the α subunit (Fig. 6A, left). As a positive control for inclusion of mRNA from carotid body type I cells, transcripts for tyrosine hydroxylase were also identified (Fig. 6B, left). In marked contrast, end point RT-PCR (Fig. 6B, right) on single acutely isolated rat carotid body type I cells identified no STREX amplicon but identified clear amplicons for the ZERO and the low molecular weight amplicon of the BKCa α subunit (n = 5; Fig. 6A, right) as well as tyrosine hydroxylase (n = 5; Fig. 6B, right). It would appear, therefore, that the AMPK-sensitive ZERO variant of the BKCa α subunit is expressed in the oxygen-sensing rat carotid body type I cells, whereas expression of the AMPK-insensitive STREX variant is restricted to other cell types within the carotid body.

FIGURE 6.

Expression of BKCa splice variants in the whole carotid body and acutely isolated carotid body type I cells. A, gel shows the STREX, ZERO, and low molecular weight (LMA) BKCa amplicons identified by RT-PCR from total mRNA extracted from whole carotid bodies (Total CB) (left) and from a single acutely isolated carotid body type I cell (right). B, paired samples for A and B showing the tyrosine hydroxylase amplicon (TH). Controls shown represent aspirants of extracellular medium.

DISCUSSION

The findings of the present investigation are consistent with the hypothesis that alternative pre-mRNA splicing of BKCa α subunits provides a mechanism by which AMPK-dependent regulation of cell function may be modulated in a cell-specific manner.

First of all, we provided evidence that AMPK regulates BKCa channels in a splice variant-specific manner. Thus, two AMPK agonists with different mechanisms of action, namely AICAR and A-769662, were shown to inhibit ion channel currents carried by the ZERO but not the STREX variant of the BKCa α subunit. Moreover, the AMPK antagonist compound C abolished channel regulation by each of these AMPK agonists. It is highly unlikely, therefore, that AICAR and A-769662 mediate the same splice variant-specific regulation of BKCa by any mechanism other than AMPK activation. Nonetheless, off target effects are still possible. Therefore, we extended our studies and demonstrated for the first time that intracellular dialysis from a patch pipette of recombinant human α2β2γ1 heterotrimers, activated by prior thiophosphorylation, also inhibited ion channel currents carried by the ZERO but not the STREX variant of the BKCa α subunit. Our data provide, therefore, the strongest evidence possible that AMPK regulates BKCa channel function in a splice variant-specific manner.

Nonetheless, subsequent studies on BKCa α subunit phosphorylation proved surprising. We showed that AMPK phosphorylated both the ZERO and STREX variants of the BKCa α subunit in a manner stimulated by AMP, despite the fact that AMPK only inhibited channel currents carried by the ZERO and not the STREX variant. The fact that channel currents carried by the STREX variant remained functionally unaffected by AMPK although the α subunit was still phosphorylated was interesting enough. However, we demonstrated that inclusion of the STREX insert within the BKCa α subunit increased the stoichiometry of phosphorylation from 0.96 to 1.5 mol/mol (i.e. that an increase in AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of the α subunit ablated channel regulation).

Within the STREX insert, a sequence was identified (RSERDCSCMSG) that is a partial fit to the recognition motif previously defined for AMPK (27). Mutation of the serine residue within this sequence (S657A) not only reduced the stoichiometry of phosphorylation (from 1.5 to 1.1 mol/mol) but restored inhibition of the current by AMPK (i.e. this mutation restored the ZERO phenotype) (Figs. 2 and 4). The simplest hypothesis to explain these data is that phosphorylation by AMPK of Ser-657 within the STREX insert ablates the inhibitory effect of phosphorylation by the same enzyme at another site(s) outside the STREX insert, although other mechanisms are possible. This has striking parallels with regulation of BKCa channels by PKA. Phosphorylation of Ser-636 in the STREX insert by PKA (21 residues upstream of Ser-657) confers channel inhibition, and this overrides the effect of phosphorylation by PKA at Ser-927 in the C-terminal region, which results in channel activation in ZERO variants. Thus, inclusion of an alternative splice insert, by introducing new phosphorylation sites, can switch the functional regulation of BKCa channels by two distinct signaling pathways (AMPK and PKA), each of which may act in opposition with respect to functional regulation of the ZERO variant.

Therefore, alternative pre-mRNA splicing of BKCa α subunits provides a molecular switch that determines channel sensitivity to AMPK, and cell type-specific regulation of splicing may be utilized to determine functional outcomes. This is supported by our findings by single cell PCR that rat carotid body type I cells, the archetypal “oxygen-sensing” cells, express exclusively the ZERO but not the STREX variant of the BKCa α subunit (Fig. 6), whereas other cell types within the carotid body (which do not monitor oxygen supply) also express the STREX variant. Consistent with the exclusive expression of the ZERO variant, both the AMPK agonist A-769662 and provision of active, thiophosphorylated recombinant AMPK by dialysis via the patch pipette markedly attenuated BKCa channel currents in carotid body type I cells (Fig. 4).

Our findings may be of more general significance, however, given that metabolic stresses (e.g. hypoxia and glucose deprivation) could regulate BKCa channels via AMPK in a manner limited by STREX expression and thereby modulate cell type-specific outcomes, such as the regulation of vascular tone by smooth muscle (30, 31) and exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells (12, 15). That this may be the case is highlighted by the fact that in adrenal chromaffin cells glucocorticoids may reduce expression of the STREX variant, whereas the release of adrenal androgens in response to stress or ACTH may increase its expression (32, 33). Such plasticity may provide for not only an adaptive mechanism by which AMPK-dependent regulation of cellular excitability can be tailored to meet physiological requirements but one that may also underpin pathophysiological outcomes. Thus, aberrant modulation of BKCa channels by AMPK may be significant in a variety of disorders where BKCa channel dysfunction has been implicated, such as hypertension (30, 34), incontinence (35), ataxia (36), and epilepsy (20).

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Programme Grants 81195 (to A. M. E., C. P., and D. G. H.), 080982 (to D. G. H.), and 082407 (to M. J. S.).

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATPγS

- adenosine 5′-O-(thiotriphosphate)

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- STREX

- stress-regulated exon

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- AICAR

- 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside

- PP1γ

- protein phosphatase-1γ

- iAMPK

- inactive AMPK.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gonzalez C., Almaraz L., Obeso A., Rigual R. (1994) Physiol. Rev. 74, 829–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. López-Barneo J., Ortega-Sáenz P., Pardal R., Pascual A., Piruat J. I. (2008) Eur. Respir. J. 32, 1386–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wyatt C. N., Mustard K. J., Pearson S. A., Dallas M. L., Atkinson L., Kumar P., Peers C., Hardie D. G., Evans A. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8092–8098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Evans A. M., Hardie D. G., Peers C., Wyatt C. N., Viollet B., Kumar P., Dallas M. L., Ross F., Ikematsu N., Jordan H. L., Barr B. L., Rafferty J. N., Ogunbayo O. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1177, 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hardie D. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 774–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hawley S. A., Boudeau J., Reid J. L., Mustard K. J., Udd L., Mäkelä T. P., Alessi D. R., Hardie D. G. (2003) J. Biol. 2, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott J. W., Hawley S. A., Green K. A., Anis M., Stewart G., Scullion G. A., Norman D. G., Hardie D. G. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 113, 274–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corton J. M., Gillespie J. G., Hawley S. A., Hardie D. G. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 229, 558–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davies S. P., Helps N. R., Cohen P. T., Hardie D. G. (1995) FEBS Lett. 377, 421–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawley S. A., Pan D. A., Mustard K. J., Ross L., Bain J., Edelman A. M., Frenguelli B. G., Hardie D. G. (2005) Cell. Metab. 2, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hurley R. L., Anderson K. A., Franzone J. M., Kemp B. E., Means A. R., Witters L. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29060–29066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sah P. (1996) Trends Neurosci. 19, 150–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tian L., Duncan R. R., Hammond M. S., Coghill L. S., Wen H., Rusinova R., Clark A. G., Levitan I. B., Shipston M. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7717–7720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tian L., Coghill L. S., McClafferty H., MacDonald S. H., Antoni F. A., Ruth P., Knaus H. G., Shipston M. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11897–11902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shipston M. J. (2001) Trends Cell. Biol. 11, 353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butler A., Tsunoda S., McCobb D. P., Wei A., Salkoff L. (1993) Science 261, 221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xie J., McCobb D. P. (1998) Science 280, 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCartney C. E., McClafferty H., Huibant J. M., Rowan E. G., Shipston M. J., Rowe I. C. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17870–17876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wyatt C. N., Peers C. (1993) Neuroscience 54, 275–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Du W., Bautista J. F., Yang H., Diez-Sampedro A., You S. A., Wang L., Kotagal P., Lüders H. O., Shi J., Cui J., Richerson G. B., Wang Q. K. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37, 733–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hawley S. A., Davison M., Woods A., Davies S. P., Beri R. K., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27879–27887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dale S., Wilson W. A., Edelman A. M., Hardie D. G. (1995) FEBS Lett. 361, 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peers C., Green F. K. (1991) J. Physiol. 437, 589–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Göransson O., McBride A., Hawley S. A., Ross F. A., Shpiro N., Foretz M., Viollet B., Hardie D. G., Sakamoto K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32549–32560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scott J. W., van Denderen B. J., Jorgensen S. B., Honeyman J. E., Steinberg G. R., Oakhill J. S., Iseli T. J., Koay A., Gooley P. R., Stapleton D., Kemp B. E. (2008) Chem. Biol. 15, 1220–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou G., Myers R., Li Y., Chen Y., Shen X., Fenyk-Melody J., Wu M., Ventre J., Doebber T., Fujii N., Musi N., Hirshman M. F., Goodyear L. J., Moller D. E. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1167–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scott J. W., Norman D. G., Hawley S. A., Kontogiannis L., Hardie D. G. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 317, 309–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gratecos D., Fischer E. H. (1974) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 58, 960–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Evans A. M., Mustard K. J., Wyatt C. N., Peers C., Dipp M., Kumar P., Kinnear N. P., Hardie D. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41504–41511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brenner R., Peréz G. J., Bonev A. D., Eckman D. M., Kosek J. C., Wiler S. W., Patterson A. J., Nelson M. T., Aldrich R. W. (2000) Nature 407, 870–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Toro L., Wallner M., Meera P., Tanaka Y. (1998) News Physiol. Sci. 13, 112–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lai G. J., McCobb D. P. (2006) Endocrinology 147, 3961–3967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lai G. J., McCobb D. P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7722–7727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sausbier M., Arntz C., Bucurenciu I., Zhao H., Zhou X. B., Sausbier U., Feil S., Kamm S., Essin K., Sailer C. A., Abdullah U., Krippeit-Drews P., Feil R., Hofmann F., Knaus H. G., Kenyon C., Shipston M. J., Storm J. F., Neuhuber W., Korth M., Schubert R., Gollasch M., Ruth P. (2005) Circulation 112, 60–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meredith A. L., Thorneloe K. S., Werner M. E., Nelson M. T., Aldrich R. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36746–36752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sausbier M., Hu H., Arntz C., Feil S., Kamm S., Adelsberger H., Sausbier U., Sailer C. A., Feil R., Hofmann F., Korth M., Shipston M. J., Knaus H. G., Wolfer D. P., Pedroarena C. M., Storm J. F., Ruth P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9474–9478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]