Abstract

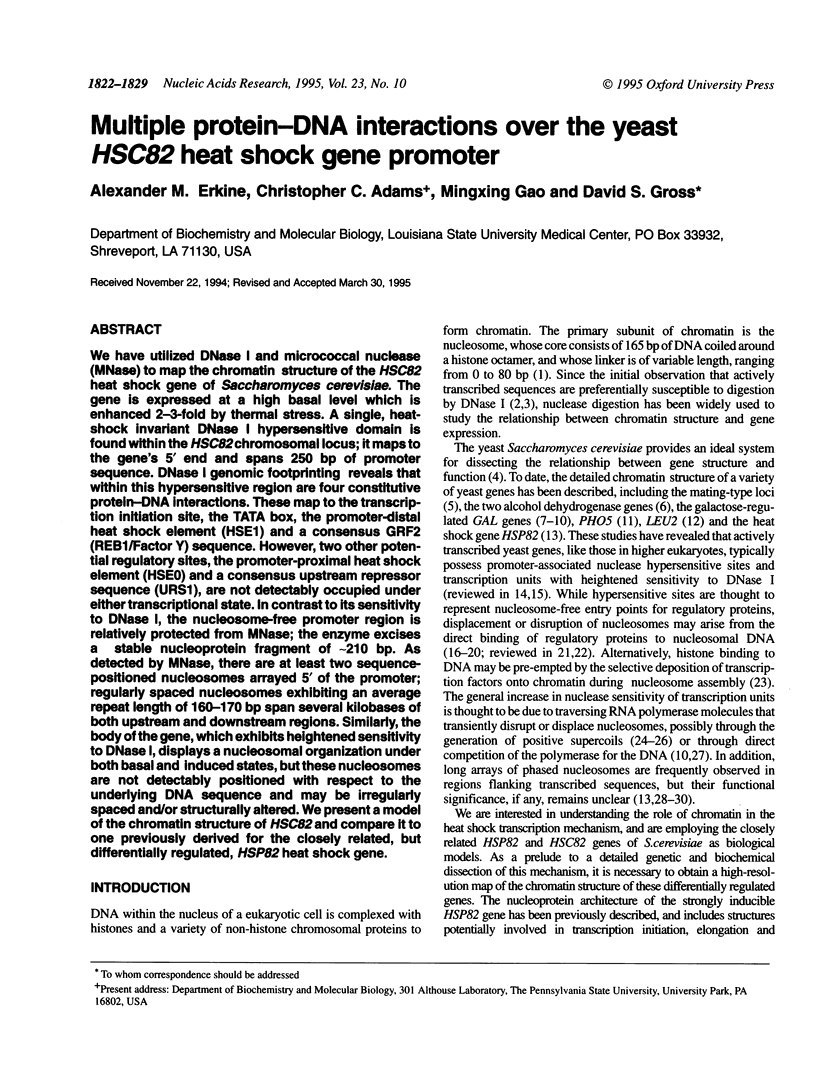

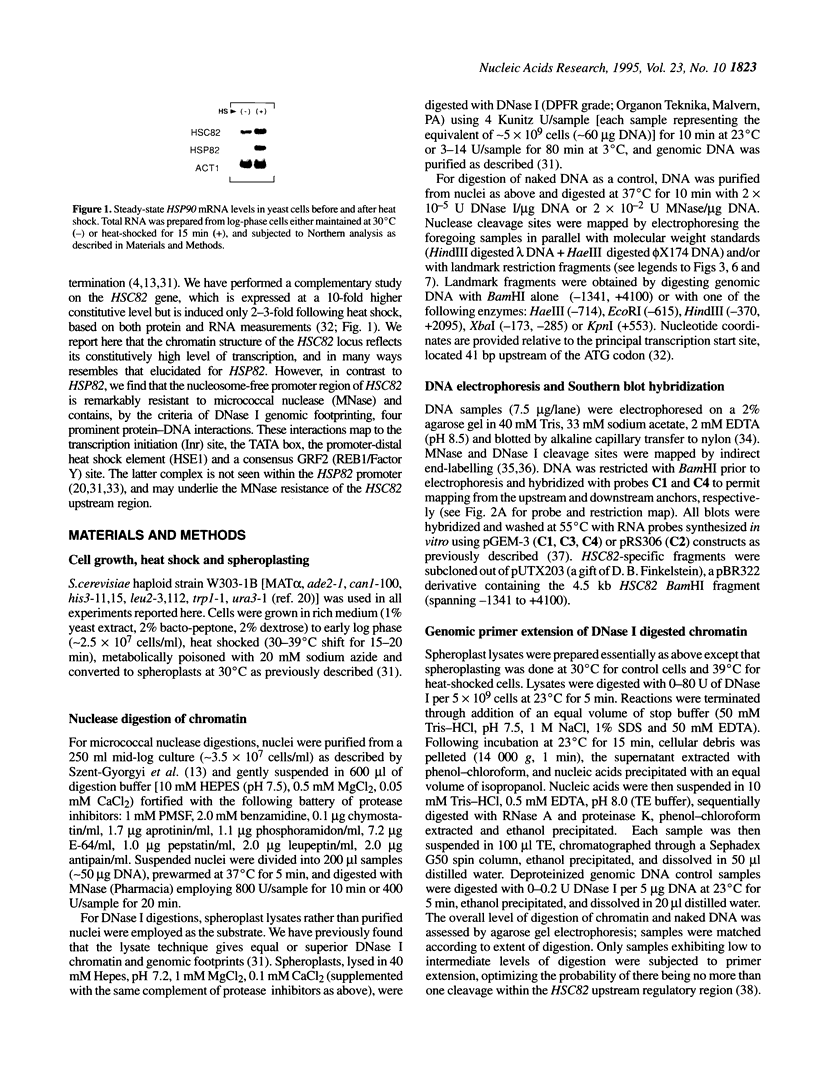

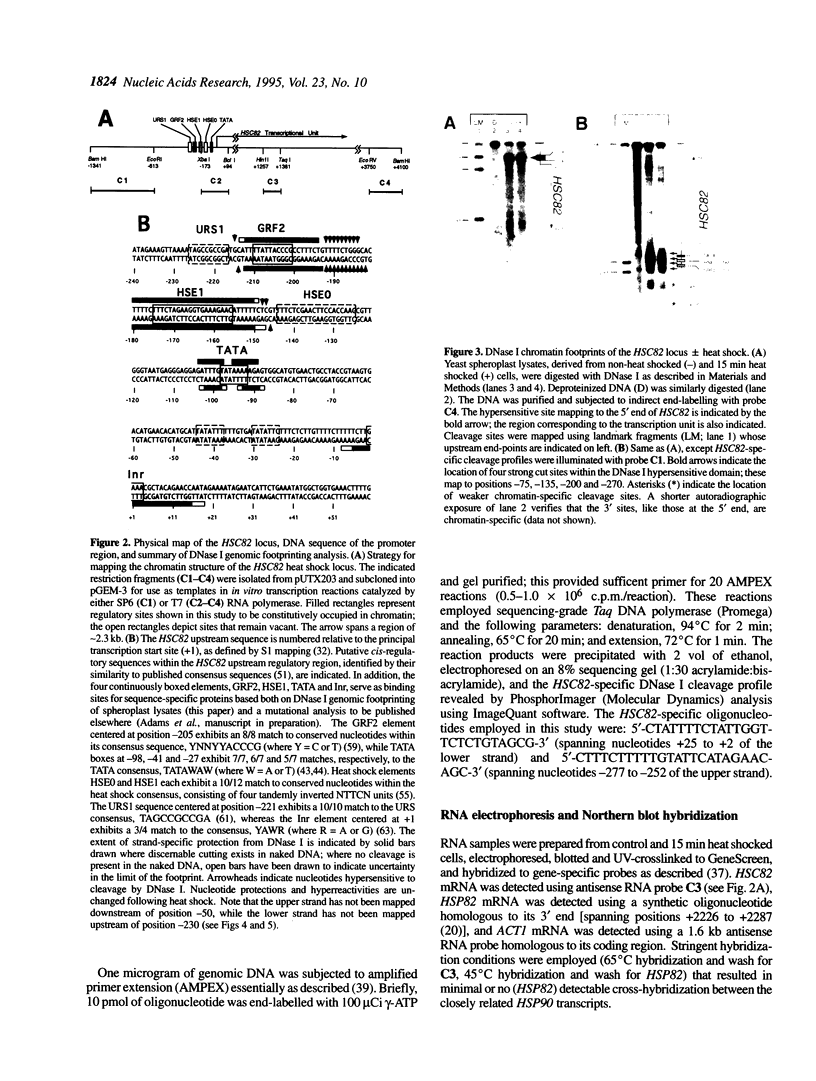

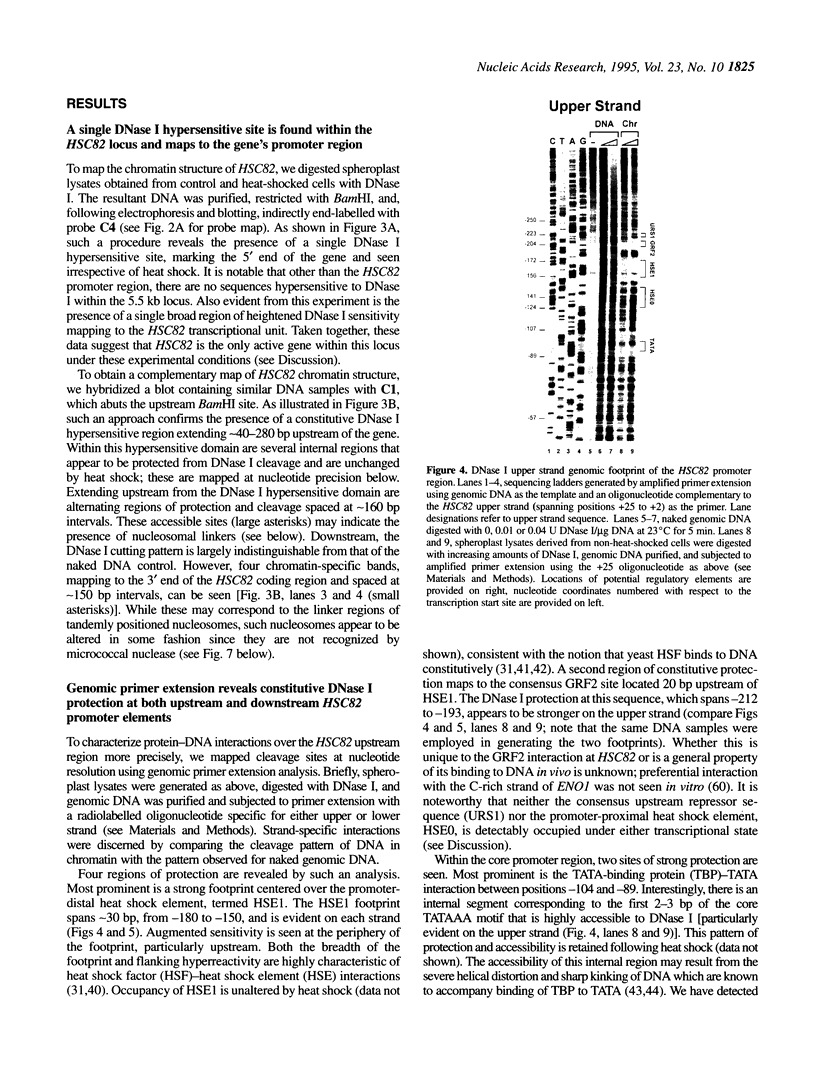

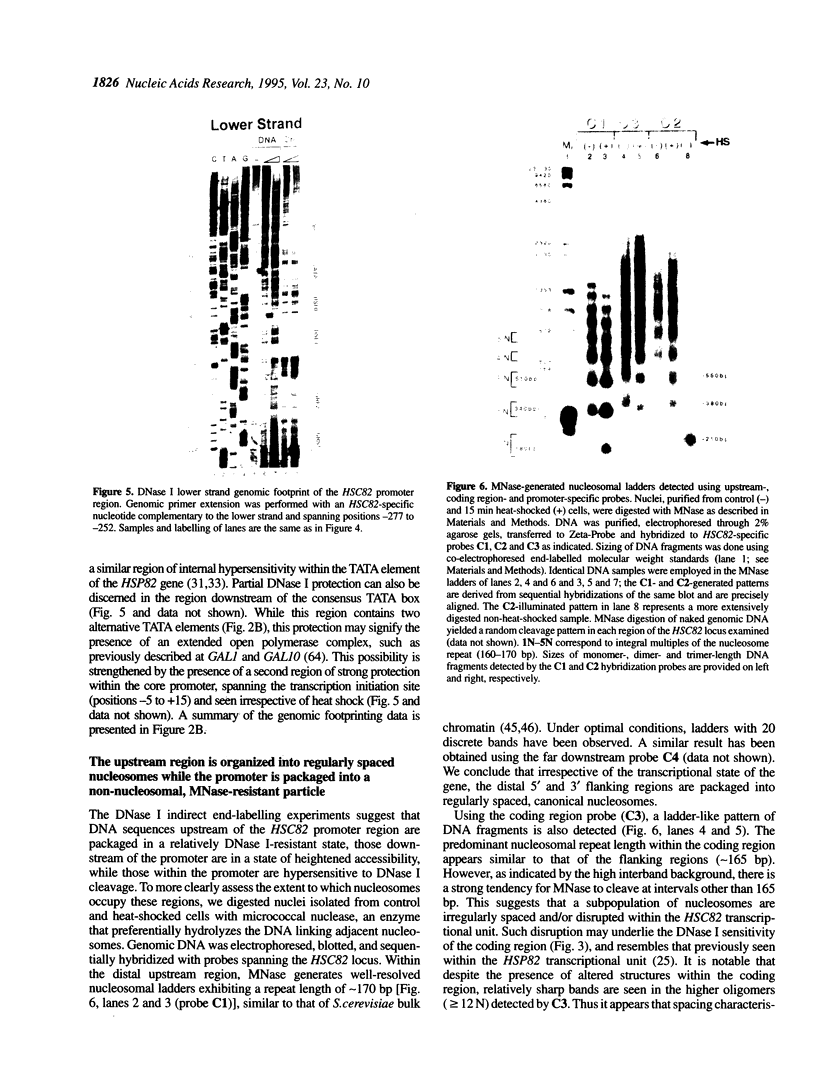

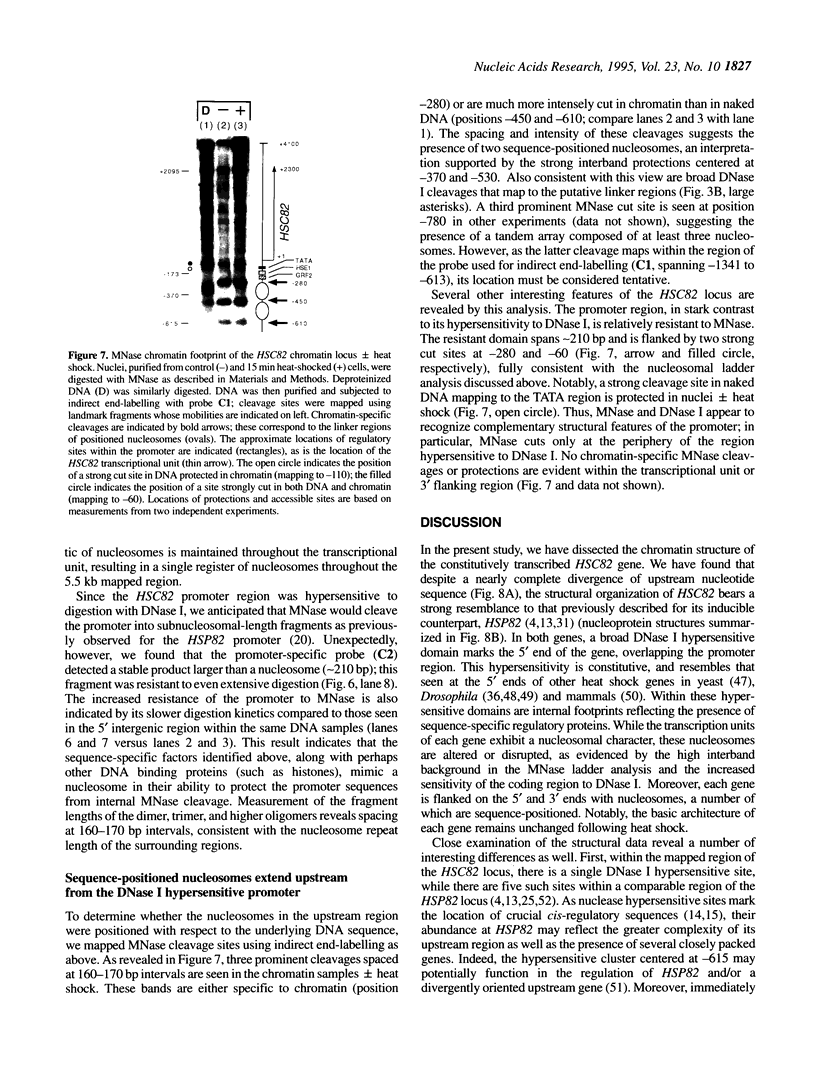

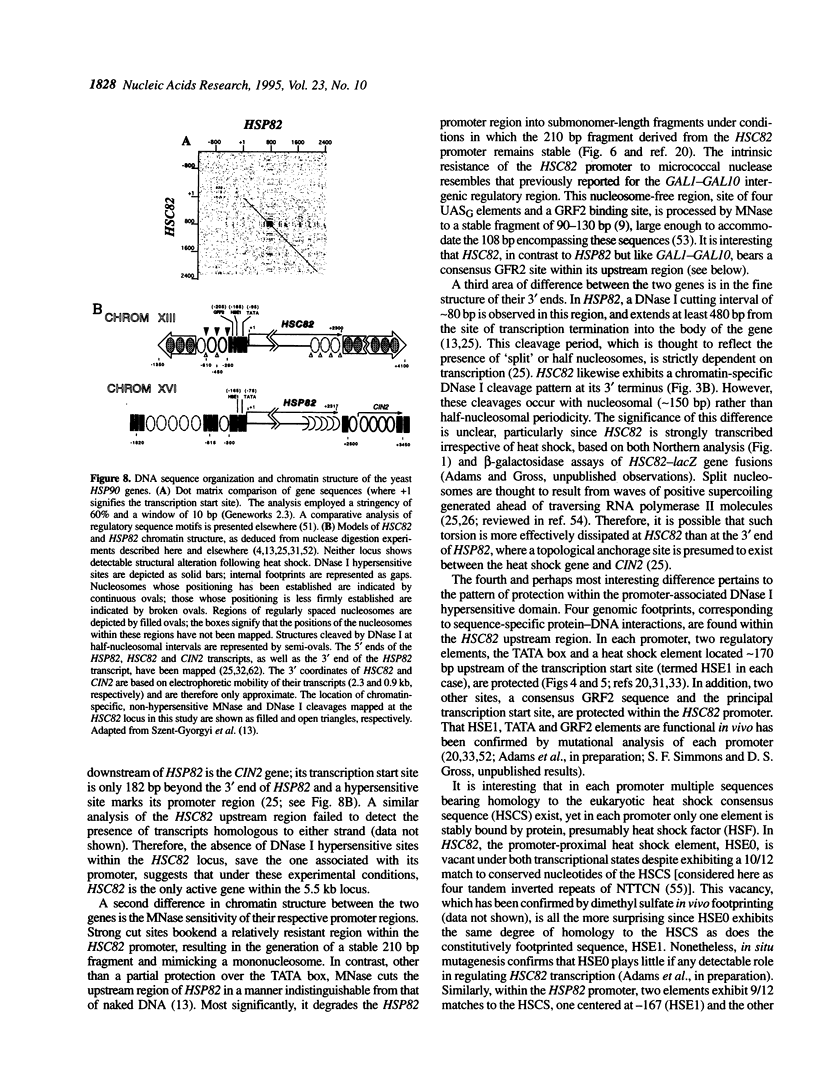

We have utilized DNase I and micrococcal nuclease (MNase) to map the chromatin structure of the HSC82 heat shock gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The gene is expressed at a high basal level which is enhanced 2-3-fold by thermal stress. A single, heat-shock invariant DNase I hypersensitive domain is found within the HSC82 chromosomal locus; it maps to the gene's 5' end and spans 250 bp of promoter sequence. DNase I genomic footprinting reveals that within this hypersensitive region are four constitutive protein-DNA interactions. These map to the transcription initiation site, the TATA box, the promoter-distal heat shock element (HSE1) and a consensus GRF2 (REB1/Factor Y) sequence. However, two other potential regulatory sites, the promoter-proximal heat shock element (HSE0) and a consensus upstream repressor sequence (URS1), are not detectably occupied under either transcriptional state. In contrast to its sensitivity to DNAase I, the nucleosome-free promoter region is relatively protected from MNase; the enzyme excises a stable nucleoprotein fragment of approximately 210 bp. As detected by MNase, there are at least two sequence-positioned nucleosomes arrayed 5' of the promoter; regularly spaced nucleosomes exhibiting an average repeat length of 160-170 bp span several kilobases of both upstream and downstream regions. Similarly, the body of the gene, which exhibits heightened sensitivity to DNase I, displays a nucleosomal organization under both basal and induced states, but these nucleosomes are not detectably positioned with respect to the underlying DNA sequence and may be irregularly spaced and/or structurally altered. We present a model of the chromatin structure of HSC82 and compare it to one previously derived for the closely related, but differentially regulated, HSP82 heat shock gene.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams C. C., Gross D. S. The yeast heat shock response is induced by conversion of cells to spheroplasts and by potent transcriptional inhibitors. J Bacteriol. 1991 Dec;173(23):7429–7435. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7429-7435.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer A., Rudolph H., Hinnen A., Hörz W. Removal of positioned nucleosomes from the yeast PHO5 promoter upon PHO5 induction releases additional upstream activating DNA elements. EMBO J. 1986 Oct;5(10):2689–2696. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J., Ananthan J., Voellmy R. Key features of heat shock regulatory elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Sep;8(9):3761–3769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer T. K., Cordingley M. G., Wolford R. G., Hager G. L. Transcription factor access is mediated by accurately positioned nucleosomes on the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Feb;11(2):688–698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovich K. A., Farrelly F. W., Finkelstein D. B., Taulien J., Lindquist S. hsp82 is an essential protein that is required in higher concentrations for growth of cells at higher temperatures. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Sep;9(9):3919–3930. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. E., Amin J., Schiller P., Voellmy R., Scott W. A. Determinants for the DNase I-hypersensitive chromatin structure 5' to a human HSP70 gene. J Mol Biol. 1988 Sep 5;203(1):107–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmen A. A., Holland M. J. The upstream repression sequence from the yeast enolase gene ENO1 is a complex regulatory element that binds multiple trans-acting factors including REB1. J Biol Chem. 1994 Apr 1;269(13):9790–9797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright I. L., Elgin S. C. Nucleosomal instability and induction of new upstream protein-DNA associations accompany activation of four small heat shock protein genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Mar;6(3):779–791. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G., Thoma F. Chromatin transitions during activation and repression of galactose-regulated genes in yeast. EMBO J. 1993 Dec;12(12):4603–4613. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasman D. I., Lue N. F., Buchman A. R., LaPointe J. W., Lorch Y., Kornberg R. D. A yeast protein that influences the chromatin structure of UASG and functions as a powerful auxiliary gene activator. Genes Dev. 1990 Apr;4(4):503–514. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costlow N. A., Simon J. A., Lis J. T. A hypersensitive site in hsp70 chromatin requires adjacent not internal DNA sequence. Nature. 1985 Jan 10;313(5998):147–149. doi: 10.1038/313147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin S. C. The formation and function of DNase I hypersensitive sites in the process of gene activation. J Biol Chem. 1988 Dec 25;263(36):19259–19262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly F. W., Finkelstein D. B. Complete sequence of the heat shock-inducible HSP90 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1984 May 10;259(9):5745–5751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fascher K. D., Schmitz J., Hörz W. Role of trans-activating proteins in the generation of active chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1990 Aug;9(8):2523–2528. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedor M. J., Kornberg R. D. Upstream activation sequence-dependent alteration of chromatin structure and transcription activation of the yeast GAL1-GAL10 genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Apr;9(4):1721–1732. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedor M. J., Lue N. F., Kornberg R. D. Statistical positioning of nucleosomes by specific protein-binding to an upstream activating sequence in yeast. J Mol Biol. 1988 Nov 5;204(1):109–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M., Xiao H., Lis J. T. Fine structure analyses of the Drosophila and Saccharomyces heat shock factor--heat shock element interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994 Jan 25;22(2):167–173. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furter-Graves E. M., Hall B. D. DNA sequence elements required for transcription initiation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe ADH gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1990 Sep;223(3):407–416. doi: 10.1007/BF00264447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galas D. J., Schmitz A. DNAse footprinting: a simple method for the detection of protein-DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978 Sep;5(9):3157–3170. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.9.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garel A., Axel R. Selective digestion of transcriptionally active ovalbumin genes from oviduct nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Nov;73(11):3966–3970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina C., Lis J. T. DNA melting on yeast RNA polymerase II promoters. Science. 1993 Aug 6;261(5122):759–762. doi: 10.1126/science.8342041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D. S., Adams C. C., Lee S., Stentz B. A critical role for heat shock transcription factor in establishing a nucleosome-free region over the TATA-initiation site of the yeast HSP82 heat shock gene. EMBO J. 1993 Oct;12(10):3931–3945. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D. S., English K. E., Collins K. W., Lee S. W. Genomic footprinting of the yeast HSP82 promoter reveals marked distortion of the DNA helix and constitutive occupancy of heat shock and TATA elements. J Mol Biol. 1990 Dec 5;216(3):611–631. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D. S., Garrard W. T. Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:159–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse J. M., Engelke D. R. Direct sequence and footprint analysis of yeast DNA by primer extension. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:550–562. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94042-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen B. K., Pelham H. R. Constitutive binding of yeast heat shock factor to DNA in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Nov;8(11):5040–5042. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M., Davis R. W. Sequences that regulate the divergent GAL1-GAL10 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Aug;4(8):1440–1448. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. L., Nikolov D. B., Burley S. K. Co-crystal structure of TBP recognizing the minor groove of a TATA element. Nature. 1993 Oct 7;365(6446):520–527. doi: 10.1038/365520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Geiger J. H., Hahn S., Sigler P. B. Crystal structure of a yeast TBP/TATA-box complex. Nature. 1993 Oct 7;365(6446):512–520. doi: 10.1038/365512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg R. D., Stryer L. Statistical distributions of nucleosomes: nonrandom locations by a stochastic mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988 Jul 25;16(14A):6677–6690. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.6677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S., Garrard W. T. Positive DNA supercoiling generates a chromatin conformation characteristic of highly active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Nov 1;88(21):9675–9679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S., Garrard W. T. Transcription-induced nucleosome 'splitting': an underlying structure for DNase I sensitive chromatin. EMBO J. 1991 Mar;10(3):607–615. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S., Garrard W. T. Uncoupling gene activity from chromatin structure: promoter mutations can inactivate transcription of the yeast HSP82 gene without eliminating nucleosome-free regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Oct 1;89(19):9166–9170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. F., Wang J. C. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Oct;84(20):7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr D. Chromatin structure and regulation of the eukaryotic regulatory gene GAL80. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Nov 15;90(22):10628–10632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr D., Kovacic R. T., Van Holde K. E. Quantitative analysis of the digestion of yeast chromatin by staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1977 Feb 8;16(3):463–471. doi: 10.1021/bi00622a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr D. The chromatin structure of an actively expressed, single copy yeast gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983 Oct 11;11(19):6755–6773. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.19.6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luche R. M., Sumrada R., Cooper T. G. A cis-acting element present in multiple genes serves as a repressor protein binding site for the yeast CAR1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Aug;10(8):3884–3895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García J. F., Estruch F., Pérez-Ortín J. E. Chromatin structure of the 5' flanking region of the yeast LEU2 gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1989 Jun;217(2-3):464–470. doi: 10.1007/BF02464918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel D., Caplan A. J., Lee M. S., Adams C. C., Fishel B. R., Gross D. S., Garrard W. T. Basal-level expression of the yeast HSP82 gene requires a heat shock regulatory element. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Nov;9(11):4789–4798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse R. H. Nucleosome disruption by transcription factor binding in yeast. Science. 1993 Dec 3;262(5139):1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.8248805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. A. The regulation of yeast mating-type chromatin structure by SIR: an action at a distance affecting both transcription and transposition. Cell. 1982 Sep;30(2):567–578. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedospasov S. A., Georgiev G. P. Non-random cleavage of SV40 DNA in the compact minichromosome and free in solution by micrococcal nuclease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980 Jan 29;92(2):532–539. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson D. S., Morse R. H. Effect of transcription of yeast chromatin on DNA topology in vivo. EMBO J. 1990 Jun;9(6):1873–1881. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piña B., Brüggemeier U., Beato M. Nucleosome positioning modulates accessibility of regulatory proteins to the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Cell. 1990 Mar 9;60(5):719–731. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90087-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed K. C., Mann D. A. Rapid transfer of DNA from agarose gels to nylon membranes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985 Oct 25;13(20):7207–7221. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.20.7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledziewski A., Young E. T. Chromatin conformational changes accompany transcriptional activation of a glucose-repressed gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Jan;79(2):253–256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger P. K., Lewis M. J., Pelham H. R. Heat shock factor is regulated differently in yeast and HeLa cells. Nature. 1987 Sep 3;329(6134):81–84. doi: 10.1038/329081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaren J., Chalkley R. The structure and assembly of active chromatin. Trends Genet. 1990 Feb;6(2):52–56. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90074-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szent-Gyorgyi C., Isenberg I. The organization of oligonucleosomes in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983 Jun 11;11(11):3717–3736. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.11.3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szent-Györgyi C., Finkelstein D. B., Garrard W. T. Sharp boundaries demarcate the chromatin structure of a yeast heat-shock gene. J Mol Biol. 1987 Jan 5;193(1):71–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma F., Simpson R. T. Local protein-DNA interactions may determine nucleosome positions on yeast plasmids. Nature. 1985 May 16;315(6016):250–252. doi: 10.1038/315250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma F. Structural changes in nucleosomes during transcription: strip, split or flip? Trends Genet. 1991 Jun;7(6):175–177. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90429-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite M. F., Bossier P., Fitch I. T. A highly conserved sequence in yeast heat shock gene promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988 Dec 23;16(24):11845–11845. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.24.11845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub H., Groudine M. Chromosomal subunits in active genes have an altered conformation. Science. 1976 Sep 3;193(4256):848–856. doi: 10.1126/science.948749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederrecht G., Shuey D. J., Kibbe W. A., Parker C. S. The Saccharomyces and Drosophila heat shock transcription factors are identical in size and DNA binding properties. Cell. 1987 Feb 13;48(3):507–515. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe A. P. Transcription: in tune with the histones. Cell. 1994 Apr 8;77(1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman J. L., Buchman A. R. Multiple functions of nucleosomes and regulatory factors in transcription. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993 Mar;18(3):90–95. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90160-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. The 5' ends of Drosophila heat shock genes in chromatin are hypersensitive to DNase I. Nature. 1980 Aug 28;286(5776):854–860. doi: 10.1038/286854a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Lis J. T. Germline transformation used to define key features of heat-shock response elements. Science. 1988 Mar 4;239(4844):1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.3125608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holde K. E., Lohr D. E., Robert C. What happens to nucleosomes during transcription? J Biol Chem. 1992 Feb 15;267(5):2837–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]