Abstract

Escherichia coli is the most widely used host for producing membrane proteins. Thus far, to study the consequences of membrane protein overexpression in E. coli we have focussed on prokaryotic membrane proteins as overexpression targets. Their overexpression results in the saturation of the Sec-translocon, which is a protein conducting channel in the cytoplasmic membrane that mediates both protein translocation and insertion. Saturation of the Sec-translocon leads to -i- protein misfolding/ aggregation in the cytoplasm, -ii- impaired respiration, and -iii- activation of the Arc response, which leads to inefficient ATP production and the formation of acetate. The overexpression yields of eukaryotic membrane proteins in E. coli are usually much lower than those of prokaryotic ones. This may be due to differences between the consequences of the overexpression of pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins in E. coli. Therefore, we have now also studied in detail how the overexpression of a eukaryotic membrane protein, the human KDEL receptor, affects E. coli. Surprisingly, the consequences of the overexpression of a pro- and a eukaryotic membrane protein are very similar. Strain engineering and likely also protein engineering can be used to remedy the saturation of the Sec-translocon upon the overexpression of both pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins in E. coli.

Keywords: Membrane protein production, Sec-translocon, membrane protein biogenesis, protein expression optimization, proteomics

Introduction

Overexpression of membrane proteins is often essential for structural and functional studies1. The bacterium Escherichia coli is the most widely used host for the overexpression of membrane proteins2,3,4. Unfortunately, in E. coli both yields and quality of especially eukaryotic membrane proteins are often insufficient for structural and functional studies. Recently, we have started with the identification of the bottlenecks hampering the overexpression of membrane proteins in E. coli5,6. Their identification may help to design strategies to improve membrane protein overexpression yields in E. coli.

Using a proteomics approach, we have studied the consequences of the overexpression of prokaryotic membrane proteins in the widely used protein production strain BL21(DE3)pLysS5. In this strain overexpression is driven by the T7 RNA polymerase7. The expression of this polymerase is controlled by the isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) inducible lacUV5 promoter, which is a more powerful variant of the wild-type lac promoter7. In BL21(DE3)pLysS T7 lysozyme, a natural inhibitor of the T7 RNA polymerase, is expressed under non-inducing conditions from the pLysS plasmid8. The T7 lysozyme inhibits background activity of T7 RNA polymerase due to leaky expression. Overexpression of prokaryotic membrane proteins in BL21(DE3)pLysS results in saturation of the cytoplasmic membrane protein translocation machinery, the Sec-translocon5,6. This protein conducting channel is situated in the cytoplasmic membrane and mediates both the insertion of membrane proteins into and the translocation of proteins across the membrane9. Insufficient capacity of the Sec-translocon leads to -i- a heat shock response and the accumulation of cytoplasmic aggregates containing a variety of different proteins including the target protein, -ii- a strong reduction in respiratory capacity leading to decreased oxygen consumption rates, and -iii- the activation of the Arc two-component system, which mediates adaptive responses to changing respiratory states10. The Arc-response induces the acetate-phosphotransacetylase pathway for ATP production and down-regulates components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. As a consequence, cells generate ATP very inefficiently and produce acetate. The production of acetate leads to acidification of the culture medium.

To complement the studies on the overexpression of prokaryotic membrane proteins in BL21(DE3)pLysS, we have studied the consequences of their overexpression in the E. coli strains C41(DE3) and C43(DE3)6. These two strains are derived from BL21(DE3) and were selected for their improved (membrane) protein overexpression characteristics11. In C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) the lacUV5 promoter mutated back to the less powerful wild-type lac promoter6. This promoter reversion in C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) is the key to their for many membrane proteins improved overexpression characteristics6. It results in much lower amounts of T7 RNA polymerase upon IPTG induction6. Subsequent slower transciption/ translation rates of the target membrane protein ensure that the Sec-translocon has a higher capacity to integrate the overexpressed proteins in the cytoplasmic membrane6.

It has been shown that in E. coli the biogenesis of a set of heterologous membrane proteins is, just like that of most native membrane proteins, mediated by the signal recognition particle (SRP)/ Sec-translocon/ YidC pathway12. However, the yields of eukaryotic membrane proteins in E. coli are usually much lower than those of prokaryotic membrane proteins1,6,13. This may be due to different consequences of the overexpression of pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins in E. coli. Recently, we compared the cytoplasmic membrane proteomes of E. coli strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) overexpressing the human KDEL receptor (hKDEL) fused to Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) by 2D BN/ SDS-PAGE14. To our surprise no effects on the cytoplasmic membrane proteome were identified that were different from the ones caused by prokaryotic membrane protein overexpression5,6,14. Therefore, to follow up on this unexpected observation we now also analysed total cell lysates of cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP and control cells using 2D gel electrophoresis. The 2D gel electrophoresis analysis of whole cell lysates was complemented with immuno-blotting, enzymatic activity assays and aggregate isolations. Our analysis showed that the consequences of the overexpression of a pro- and a eukaryotic membrane protein in E. coli are very similar. Strategies to improve overexpression yields of membrane proteins in E. coli are discussed.

Results

Characterization of E. coli cells overexpressing the human KDEL receptor

Thus far, to study the consequences of membrane protein overexpression in E. coli we have focussed on prokaryotic membrane proteins as overexpression targets5,6. Yields of eukaryotic membrane proteins in E. coli are usually much lower than those of prokaryotic ones. This may be due to differences between the consequences of the overexpression of pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins. Therefore, we decided to also study the consequences of the overexpression of a eukaryotic membrane protein in E. coli in detail. In this study hKDEL served as model eukaryotic membrane protein. hKDEL is involved in protein trafficking in the endoplasmic reticulum15. According to topology predictions it consists of seven transmembrane segments connected by short loops and it has an Nout – Cin topology

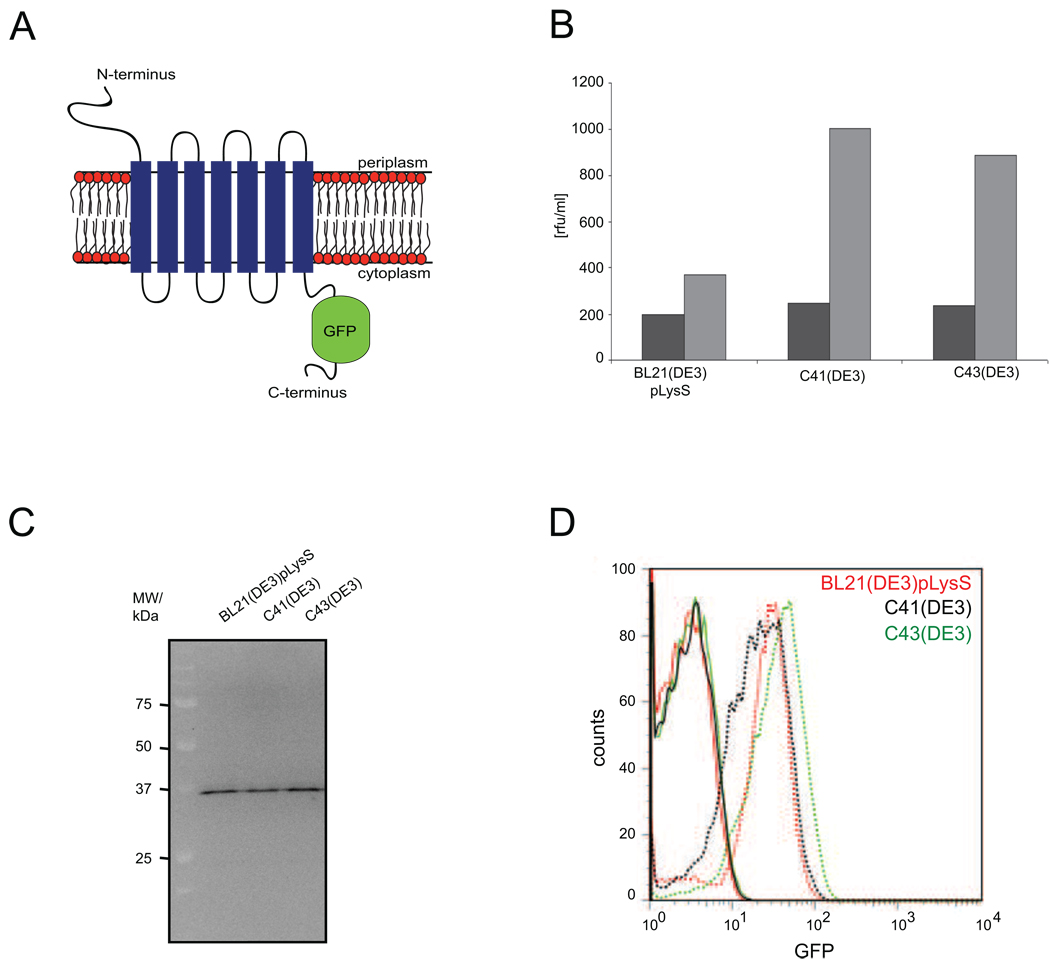

Consistent with our previous studies, hKDEL was expressed from a pET28a+-derived vector as a C-terminal GFP fusion13,16,17. No signal sequence was engineered to the N-terminus of hKDEL since it has only a very short N-terminal domain that has to be translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane (four amino acids according to TOPCON consensus prediction service, topcon.cbr.su.se). The GFP-moiety greatly facilitates monitoring expression yields in the cytoplasmic membrane13,17. Notably, GFP fluorescence can be used to monitor the integration of a membrane protein-GFP fusion into the membrane, however, it does not provide any information about the folding state of the in the membrane integrated protein (see e.g., 18). hKDEL-GFP was expressed in the E. coli strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3). The expression conditions used were similar to the ones described in our previous studies (see “Material and Methods”)5,6,16. As shown by a combination of whole cell and in-gel fluorescence measurements, hKDEL-GFP could be expressed as the full-length fusion in all three strains (Figure 1B, C). Due to their hydrophobicity membrane proteins usually migrate faster than expected in 1D SDS-PAGE19,20. Indeed, as observed before hKDEL-GFP runs at a position of approximately 37 kDa, rather than at its expected molecular weight of 52.4 kDa (hKDEL: 24.5 kDa, GFP: 26.9 kDa and connecting linker: 1 kDa)17,13. Not surprisingly, hKDEL overexpression yields in C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) were higher than in BL21(DE3)pLysS. With flow cytometry it was shown that the cultures overexpressing hKDEL-GFP and the controls consisted of homogenous populations of cells (Figure 1D). Based upon whole cell fluorescence and using purified GFP as a standard we calculated that BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) express approximately 55, 100 and 85 hKDEL-GFP molecules per cell, respectively13. These yields are considerably lower than the ones of most prokaryotic membrane proteins6,13.

Figure 1. Analysis of hKDEL-GFP overexpression in E. coli strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3).

A. Topology model of hKDEL-GFP. B. Expression yields of hKDEL-GFP in BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) monitored using whole cell fluorescence. hKDEL-GFP expression was induced for 4h as described in “Materials and Methods”. Cells carrying the empty overexpression vector served as controls. Dark gray bars: control cells; light gray bars: hKDEL-GFP expressing cells. Experiments were repeated 3 times and reproducible within 10%. Yields were too low for reliable ligand binding assays. C. In-gel fluorescence based detection of hKDEL-GFP in the hKDEL-GFP expressing cells that were used for whole cell fluorescent measurements in panel B. Whole cell lysates were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and in-gel fluorescence was detected as described in “Materials and Methods”. D. Expression of hKDEL-GFP monitored by flow cytrometry. Solid lines: control cells; dashed lines: hKDEL-GFP expressing cells.

In all the above described experiments hKDEL was expressed from a cDNA based clone. Since in this set-up codon usage/ gene design may hamper hKDEL expression, we also expressed hKDEL from a for E. coli based expression optimised synthetic gene (Supplementary figure 1). However, the optimised hKDEL gene did not lead to improved overexpression yields (results not shown). This is in line with attempts to improve overexpression of hKDEL in the bacterium Lactococcus lactis through gene optimization. Actually, in L. lactis gene optimization led to four times lower yields as compared to the cDNA based overexpression of hKDEL21. Therefore, we continued in our studies with the original cDNA-based hKDEL-GFP overexpression plasmid.

Consequences of the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP in E. coli

As mentioned above cultures of BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) overexpressing hKDEL-GFP and controls consisted of homogenous populations of cells. This is a prerequisite for a proteomics analysis. Recently, when we compared the cytoplasmic membrane proteomes of E. coli strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) overexpressing hKDEL-GFP by 2D BN/ SDS-PAGE no effects on the cytoplasmic membrane proteome were identified that were different from the ones caused by prokaryotic membrane protein overexpression (Supplementary figure 2, Supplementary table 1)5,6,14. For the sake of clarity it should be mentioned that in reference 14 the treatment in the statistical analysis of cytoplasmic membrane proteomes from E. coli corresponds to hKDEL-GFP overexpression14. To further study the consequences of the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP in the three strains, we now analysed total cell lysates of cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP and control cells using 2D gel electrophoresis.

Analysis of cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP by 2D gel electrophoresis, immuno-blotting and enzymatic activity assays

Total proteomes of cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP and control cells were compared by image analysis of 2D gels (Figure 2A, Supplementary figure 3, Supplementary table 2). As a first dimension denaturing immobilised pH gradient (IPG) strips (pH 4–7) were run and the second dimension was Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE. Each gel set consisted of four biological replicates. Gels were stained with colloidal Coomassie, scanned and images were subsequently analysed and compared using the PDQuest software (Bio-Rad). Subsequent statistical analysis of the 2D gels was done by ANOVA as described previously (Supplementary figure 3, Supplementary table 2)6,14. The 2D gel analysis of the whole cell lysates was complemented with immuno-blotting and enzymatic activity assays.

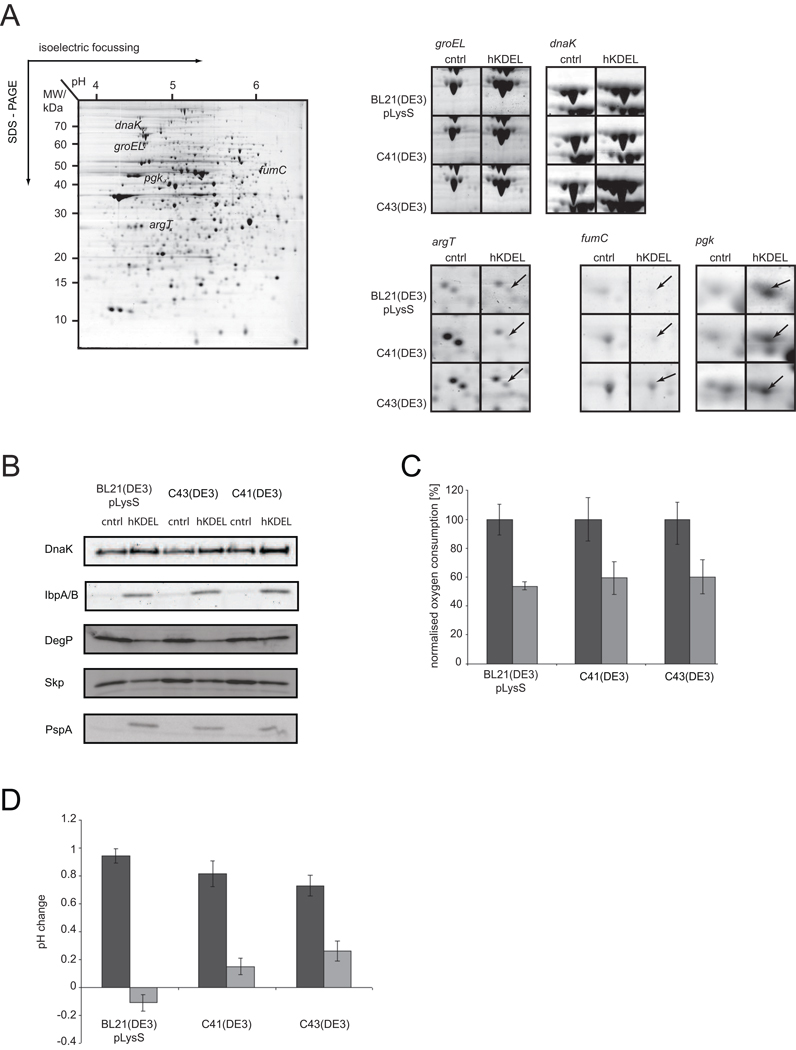

Figure 2. Analysis of cells expressing hKDEL-GFP by 2D gel electrophoresis, immuno-blotting and enzymatic activity assays.

Comparative 2D gel analysis of proteins in whole cell lysates of BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) cells with an empty overexpression vector and overexpressing hKDEL-GFP for 4 hours (see “Material and Methods”). A. A representative 2D gel with proteins of C43(DE3) control cells and zooms of regions of the 2D gels of BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) cells with an empty overexpression vector and overexpressing hKDEL-GFP with spots representing GroEL, DnaK, ArgT, FumC and Pgk. B. Proteins of whole cell lysates of BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) cells with the empty expression vector and overexpressing hKDEL-GFP were separated by means of SDS-PAGE and subsequently subjected to immuno-blotting analysis with antibodies against DnaK, IbpA/ B, DegP, Skp and PspA. C. Oxygen consumption rates were measured in whole cells. Experiments were done in triplicates. Rates of control cells were set to 100. Dark gray bars: control cells; light gray bars: cells expressing hKDEL-GFP. D. Acidification of the medium upon membrane protein overexpression was followed by pH measurements. Dark gray bars: control cells; light gray bars: cells expressing hKDEL-GFP. Experiments were done in triplicates.

The analysis of the 2D gels showed that overexpression of hKDEL-GFP in E. coli leads - just like the overexpression of a human G protein-coupled receptor22 - to the induction of the heat shock response, which is exemplified by increased levels of chaperones like GroEL, DnaK, ClpB and IbpA/ B (Supplementary table 2, Figure 2A shows zooms of spots representing GroEL and DnaK). The increased levels of DnaK and IbpA/ B were confirmed by immuno-blotting (Figure 2B). Induction of the heat shock response points to a protein misfolding/ aggregation problem in the cytoplasm23. Furthermore, levels of many secreted proteins, like Agp, CpdB, UgpB, MelA, TreA and ArgT (Supplementary table 2, Figure 2A shows a zoom of the spot representing ArgT), were decreased upon hKDEL-GFP overexpression. By means of immuno-blotting it was shown that the levels of the secreted form of the periplasmic proteins DegP and Skp, which both were not detected in the 2D gels, were also lowered upon hKDEL-GFP overexpression (Figure 2B). These observations indicate that the Sec-translocon mediated translocation of secretory proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane is impaired upon hKDEL-GFP overexpression.

In addition, the analysis of whole cell lysates showed that levels of enzymes of the citrate cycle (PfkB, FumC and Mdh) were down and levels of enzymes involved in the “payoff phase” of glycolysis (GapA and Pgk) and the acetate kinase pathway (AckA) were up upon the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP (Supplementary table 2, Figure 2A shows zooms of spots representing FumC and Pgk). This observation indicates that the Arc response is activated upon hKDEL-GFP expression10. The Arc response is activated when the quinol/ quinone (Q)-pool in the cytoplasmic membrane, which mediates the transfer of electrons from the NADH dehydrogenases/succinate dehydrogenase to the cytochrome bd/ bo3 oxidases, is in a mostly reduced state10. When the capacity of the respiratory chain is impaired, the Q-pool will become reduced. Overexpression of hKDEL-GFP leads to strongly lowered oxygen consumption rates in whole cells (Figure 2C), indicating that the capacity of the respiratory chain is indeed impaired upon hKDEL-GFP overexpression. Activation of the Arc response will lead to production of acetate via the acetate-pta pathway resulting in the acidification of the medium24. Indeed, hKDEL-GFP overexpression leads to acidification of the culture medium (Figure 2D).

Finally, by immuno-blotting it was shown that the phage shock protein A (PspA) response is induced upon hKDEL-GFP overexpression (Figure 2B). This observation indicates that hKDEL-GFP overexpression leads to cell envelope stress, which is corroborated by the lowered oxygen consumption rates in whole cells.

hKDEL-GFP overexpression leads to the formation of cytoplasmic aggregates

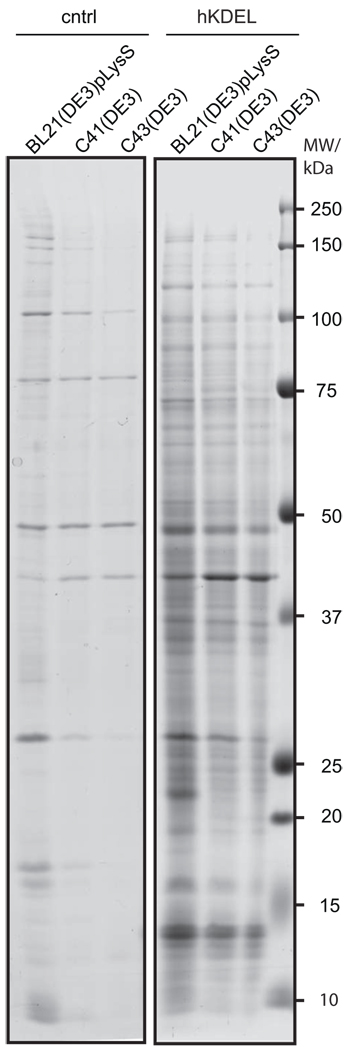

The heat shock response in cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP pointed to a protein folding/ aggregation problem in the cytoplasm. Indeed, using a Nonidet P-40-based purification protocol aggregates could be isolated from cells of all three strains when overexpressing hKDEL-GFP (Figure 3). This is in keeping with the presence of also IbpA/ B in these cells (Figure 2B). The aggregates in BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) made up around 0.8%, 0.6% and 0.15% of the total cellular protein, respectively. It is tempting to speculate that mistargeted hKDEL-GFP and/ or degradation products thereof titrate chaperones thereby reducing their availability. This will cause misfolding/ aggregation of chaperone substrates in the cytoplasm. Compared to previous observations, where overexpression of prokaryotic membrane protein-GFP fusions led to aggregation of 0.8 – 1.6 % of the total protein5, the values for hKDEL-GFP overexpression are only slightly lower.

Figure 3. Overexpression of hKDEL-GFP leads to the formation of aggregates.

Protein aggregates were isolated from BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP for 4 hours and control cells as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. The aggregates were analysed by SDS-PAGE in a 8–16% gradient gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250.

Poolman and co-workers have shown that when the levels of a membrane protein GFP fusion in the cytoplasm are sufficiently high a double band appears in immuno-blotting experiments with an antibody against GFP; with the non-fluorescent species running higher in the gel than the membrane integrated fluorescent species25. However, immuno-blotting using an antibody against GFP did not reveal any evidence for the presence of non-membrane integrated species and/ or degradation products of the fusion protein (Supplementary figure 4).

Taken together, the consequences of the overexpression of hKDEL in the E. coli strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) are similar to those of the overexpression of prokaryotic membrane proteins in these strains.

Oligomeric state of the overexpressed hKDEL-GFP

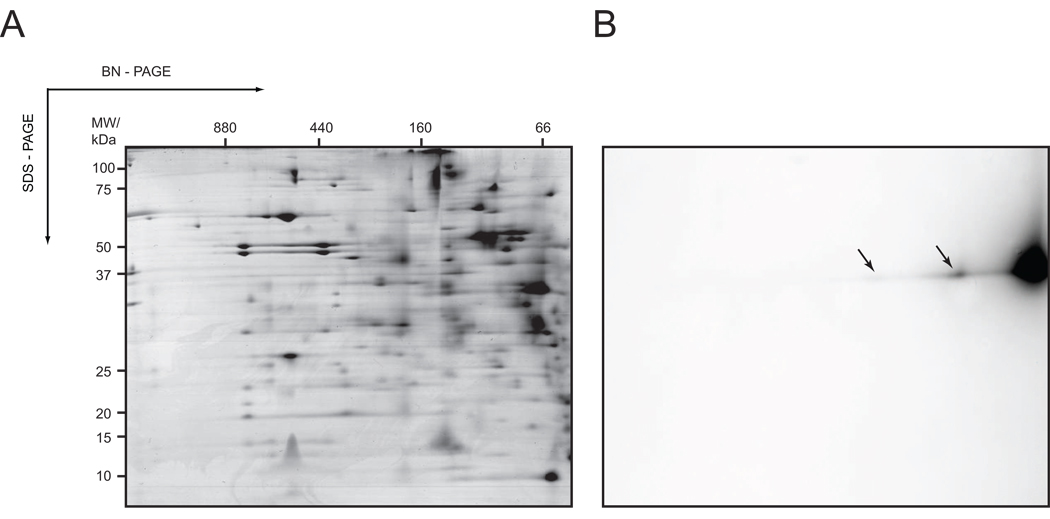

In colloidal Coomassie stained 2D BN/ SDS gels with cytoplasmic membranes from cells overexpressing prokaryotic membrane proteins these proteins could easily be detected5,6. However, hKDEL-GFP could not be visualised by colloidal Coomassie staining (Figure 4A, Supplementary table 1). Therefore, to detect hKDEL-GFP in 2D BN/ SDS gels we used in-gel fluorescence, which is many times more sensitive (Figure 4B)13,26. Indeed, in the second dimension SDS gel at the expected molecular weight of 37 kDa three fluorescent spots of different intensities appeared (Figure 4B). In the 1st dimension BN gel most of the overexpressed hKDEL-GFP runs as a complex with a mass of 66 kDa. This complex most likely represents a monomer binding Coomassie dye and/ or detergent (Figure 4B). Two additional sub-complexes, one with a native mass of 100 kDa and the other with a native mass of 160 kDa, contained the fusion protein. These complexes may very well represent either hKDEL-GFP dimers/ multimers or a complex of hKDEL-GFP with proteins involved in its biogenesis/ degradation.

Figure 4. Detection of hKDEL-GFP in 2D BN/ SDS gels by in-gel fluorescence.

Cytoplasmic membrane fractions of cells expressing hKDEL-GFP were isolated and analysed using 2D BN/ SDS-PAGE combined with Coomassie staining and in-gel fluorescence as described in “Material and Methods” A. 2D BN/ SDS gel with the membrane fraction of C41(DE3), which showed the highest yield for hKDEL-GFP overexpression and is also representative for the membrane fractions of BL21(DE3)pLysS and C43(DE3) cells expressing hKDEL-GFP, stained with colloidal Coomassie. B. Prior to Coomassie staining hKDEL-GFP was detected in the 2D BN/ SDS gel using in-gel fluorescence. hKDEL-GFP in the 100 and 160 kDa complexes is marked with arrows.

Discussion

We have studied the consequences of the overexpression of a human membrane protein, hKDEL, C-terminally fused to GFP in the widely used E. coli protein production strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3). In all three strains the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP led to -i- a heat shock response and accumulation of cytoplasmic aggregates, -ii- decreased oxygen consumption rates due to a reduction in respiratory capacity, and -iii- the activation of the Arc response, which induces the acetate-phosphotransacetylase pathway for ATP production and down-regulates components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Thus, the consequences of the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP are very similar to the consequences of the overexpression of a prokaryotic membrane protein5,6. In spite of much lower yields as compared to the ones of the prokaryotic targets used in aforementioned studies also the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP leads to the saturation of the Sec-translocon. How can these seemingly contradictory observations be explained?

Recently, it was suggested that in spite of the homology between Sec-translocons of different origins there may be subtle but critical differences between them27. For instance, residues that are critical for the functioning of the yeast Sec-translocon are not conserved in all bacterial Sec-translocons, including the one from E. coli. It has been speculated that such differences could affect the efficient recognition and processing of a heterologous membrane protein by a Sec-translocon, thereby hampering its expression27. In this respect it should be mentioned that for some polytopic membrane proteins it has been shown that upon release of their transmembrane segments from the protein conducting channel of the Sec-translocon they - for at least some time - remain intimately and specifically associated with components of the Sec-translocon and in E. coli also with the auxiliary Sec-translocon component YidC28,29,30. It has been suggested that this sequential triage is required for the proper folding of a polytopic membrane protein as a whole. Thus, although the Sec-translocon and YidC in E. coli may be able to assist the biogenesis of a heterologous membrane protein, they may not optimally be suited for it. As a consequence, hKDEL-GFP may interact longer than a native membrane protein with them, thereby saturating their capacity. This would explain why in spite of much lower yields, the overexpression of hKDEL-GFP leads to the same consequences as the overexpression of a prokaryotic membrane protein. Interestingly, the analysis of 2D BN/ SDS gels of cytoplasmic membranes of cells overexpressing hKDEL-GFP using in-gel fluorescence indicated that hKDEL-GFP also occurs in complexes. It is tempting to speculate that these represent complexes of the Sec-translocon and/ or YidC that are kept occupied by hKDEL-GFP. Also other components involved in the biogenesis of membrane proteins in E. coli may be less compatible with heterologous membrane proteins than with native membrane proteins. hKDEL-GFP expression levels in C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) are higher than in BL21(DE3)pLysS. Also this observation is in support of a Sec-translocon capacity problem. Upon induction with IPTG, T7 RNA polymerase levels in cells of these strains are considerably lower than in BL21(DE3)pLysS cells6. This will result in lower expression of hKDEL-GFP and consequently in less pressure on the Sec-translocon in C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) compared to BL21(DE3)pLysS. As a result, less mistargeted hKDEL-GFP proteins and degradation products thereof will accumulate in the cytoplasm. Indeed, in C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) less aggregate formation in the cytoplasm occurs upon hKDEL-GFP overexpression compared to BL21(DE3)pLysS. However, based on an SDS-PAGE/ immuno-blotting based GFP folding assay we could only detect membrane-integrated hKDEL-GFP25. This result indicates that levels of the fusion protein in the cytoplasm must be very low, but still high enough to induce some aggregate formation. Alternatively, the aggregate formation could also be caused by degradation products of hKDEL-GFP in the cytoplasm that cannot be identified with an antibody against GFP. If this would be the case, their levels are also low. Although we cannot exclude that hKDEL-GFP is degraded in the membrane, all our data indicate that this is not a major issue.

Taken together, all our data indicate that in E. coli the saturation of the Sec-translocon is the main bottleneck that hampers the overexpression of both pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins. Interestingly, a recent study on the physiological responses to the overexpression of the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in L. lactis showed that CFTR expression leads to a variety of different stresses but not to saturation of the Sec-translocon31. However, as suggested by the authors, CFTR itself may be toxic to L. lactis thereby preventing that expression levels can be reached that lead to the saturation of the Sec-translocon.

Codon usage/ gene design does not seem to be a bottleneck for the overexpression of hKDEL in E. coli. However, it is possible that the currently used algorithms for optimising genes for expression in E. coli, which have been developed for soluble proteins, are not well suited for designing genes for the optimal expression of membrane proteins in this bacterium.

It has been shown that E. coli strains can be isolated/ engineered that allow increased membrane protein production yields11,32,33,6,34. Only for some of these strains there is a clear explanation why they have improved membrane protein overexpression characteristics. Notably, upon membrane protein overexpression they all are somehow able to prevent to at least some extent saturation of their Sec-translocon capacity. The effects of the reversion of the promoter governing the expression of the T7 RNA polymerase in the C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) strains on their Sec-translocon capacity upon membrane protein overexpression are prime examples of this (see above). Furthermore, a derivative strain of E. coli BL21(DE3), termed Lemo21(DE3), was engineered in which the activity of the T7 RNA polymerase can be precisely controlled by its natural inhibitor T7 lysozyme6. In Lemo21(DE3) the gene encoding the T7 lysozyme is on a plasmid under control of a rhamnose promoter, which is extremely well titratable and covers a broad range of expression intensities35. In this way the amount of membrane protein produced can be easily harmonized with the Sec-translocon capacity of the cell. Finally, it has been shown that in one of the strains with improved membrane protein overexpression characteristics that was isolated by Massey-Gendel and colleagues, EXP-Rv1337-4, the copy number of the overexpression vectors used was negatively affected34. This will result in slower transcription/ translation rates thereby lowering the pressure on the Sec-translocon upon membrane protein overexpresssion34

For a number of pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins it has been shown that variants can be screened for that are more amenable to overexpression in E. coli and/ or more stable upon extraction from the cytoplasmic membrane while remaining fully functional36,37,38,39,40. It is tempting to speculate that some of these membrane protein variants are more compatible with the Sec-translocon of E. coli thereby preventing saturation of its capacity upon their overexpression.

In conclusion, all our data indicate that in E. coli the saturation of the Sec-translocon is the major bottleneck that hampers the overexpression of both pro- and eukaryotic membrane proteins. Strain engineering and likely also protein engineering can be used to remedy this bottleneck.

Material and Methods

Strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

The human KDEL receptor (hKDEL) was overexpressed as a GFP fusion in E. coli strains BL21(DE3)pLysS, C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) from a pET28a+-derived vector13. In this vector the gene encoding the to be overexpressed protein is fused through a short flexible linker (GSAGSAAGSGEF) to the genetic information encoding a GFP variant that was selected to fold well in E. coli and has the red-shifted mutation S65T and the folding mutation F64L41. The cDNA of the ERD 2.1 gene was used to construct the hKDEL-GFP overexpression vector. The for E. coli codon optimised hKDEL gene was designed and synthesised by Geneart (for sequence see supplementary figure 1). Cells were grown aerobically in Lysogeny Broth supplemented with kanamycin (50 µg/ ml) and in case of BL21(DE3)pLysS also with chloramphenicol (30 µg/ ml). Culturing conditions used were as described previously5,6. In short, cells were cultured at 30°C, protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM IPTG (final concentration) at an OD600 of 0.4 – 0.5 and cells were harvested 4 h after induction and used for further analysis. Cells with an empty expression vector were used as a control.

Monitoring hKDEL-GFP expression using whole cell and in-gel fluorescence measurements, and flow cytometry

Whole cell and in-gel fluorescence measurements were carried out as described previously13. Flow cytometry experiments were carried out essentially as described previously6. In short, cultures were diluted in ice-cold PBS to a final concentration of 106 cells/ ml. The cellular accumulation levels of GFP fusion proteins were measured by GFP fluorescence intensity. Flow cytometry was done using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) instrument. Data acquisition was performed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences), and data were analysed with FloJo software (Tree Star).

2D gel electrophoresis

2D gel electrophoresis of whole cell lysates was performed as described previously42. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250.

Isolation of cytoplasmic membranes

Cell fractionation was carried out essentially as described before using two subsequent sets of sucrose density gradients43. The protein concentration of the final membrane fraction was determined using the BCA assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce). With buffer L (50 mm TEA, 250 mm sucrose, 1 mm DTT, pH 7.5) the membrane samples were adjusted to a concentration of 2.5 mg/ ml. Aliquots were stored at −80 °C.

Analysis of cytoplasmic membrane fractions by 2D BN/ SDS-PAGE

2D BN/ SDS-PAGE was performed essentially as described previously14. Prior to Coomassie staining, hKDEL-GFP was detected using in-gel fluorescence (see above).

2D gel image analysis and statistics

For comparative standard 2D gel analysis samples were run in quadruplets, and for comparative 2D BN/ SDS-PAGE analysis in triplicate. All gels in a set represented independent samples (i.e., samples from different bacterial colonies and cultures). Gels were scanned using a GS-800 densitometer from Bio-Rad and analysed using the PDQuest software (Bio-Rad). Spot quantities were normalised using the “total density in gel image” method to compensate for non-expression related variations in spot quantities between gels, essentially as described previously6. For each spot a two-way ANOVA was performed on log transformed data with treatment (± hKDEL-GFP overexpression) and strain as factors, including interaction. The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled at 5 % and the rejection threshold (0.023) was calculated from the model p-values (H0:no factor effect) by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure44.

Protein identification by mass spectrometry

Protein spots were identified either by peptide mass finger print or by comparison to reference maps5,14. Isolation, trypsin digest and mass spectrometry were performed as described previously5. In supplementary table 2, it is indicated which reference maps were used.

Immuno-blotting

The expression levels of DnaK, GroEL, IbpA/ B, PspA, DegP and Skp in whole cell lysates were monitored by immuno-blotting analysis. Whole cells (0.05 OD600 units) were solubilised in Laemmli solubilization buffer and separated by standard SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred from the polyacrylamide gel to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). Subsequently, membranes were blocked and decorated with antisera to the components listed above as described before5,6. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Bio-Rad) were used for visualization with the ECL system (according to the instructions of the manufacturer, GE Healthcare) and a Fuji LAS 1000-Plus charge-coupled device camera.

Oxygen consumption measurements

Oxygen consumption rates in whole cells were determined as described previously5.

Isolation of protein aggregates

Protein aggregates were isolated as described previously5. 50 ml of culture were used for an aggregate isolation and analysed by SDS-PAGE in a 8–16 % gradient gel. Per lane five OD600 units were loaded.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Joen Luirink, David Vikström, Susan Schlegel and Anna Hjelm for critically reading the manuscript. This research was supported by NIH grant 5R01GM081827-03.

Abbreviations

- hKDEL

human KDEL receptor

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- SRP

signal recognition particle

- Q-pool

quinol/ quinone pool

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- TEA

triethanolamine

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- FDR

false discovery rate

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- ECL

enhanced luminol based chemiluminescence

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vinothkumar KR, Henderson R. Structures of membrane proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 2010;43:65–158. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlegel S, Klepsch M, Gialama D, Wickström D, Slotboom DJ, de Gier JW. Revolutionizing membrane protein overexpression in bacteria. Microbial Biotechnology. 2010;3:403–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grisshammer R. Understanding recombinant expression of membrane proteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner S, Bader ML, Drew D, de Gier JW. Rationalizing membrane protein overexpression. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner S, Baars L, Ytterberg AJ, Klussmeier A, Wagner CS, Nord O, Nygren PA, van Wijk KJ, de Gier JW. Consequences of membrane protein overexpression in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1527–1550. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600431-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner S, Klepsch MM, Schlegel S, Appel A, Draheim R, Tarry M, Hogbom M, van Wijk KJ, Slotboom DJ, Persson JO, de Gier JW. Tuning Escherichia coli for membrane protein overexpression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14371–14376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804090105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Studier FW, Moffatt BA. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Studier FW. Use of bacteriophage T7 lysozyme to improve an inducible T7 expression system. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90855-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.du Plessis DJ, Nouwen N, Driessen AJ. The Sec translocase. Biochim Biophys Acta. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.08.016. Article in Press. Epub 2010/08/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgellis D, Kwon O, Lin EC. Quinones as the redox signal for the arc two-component system of bacteria. Science. 2001;292:2314–2316. doi: 10.1126/science.1059361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: Mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raine A, Ullers R, Pavlov M, Luirink J, Wikberg JE, Ehrenberg M. Targeting and insertion of heterologous membrane proteins in E. coli. Biochimie. 2003;85:659–668. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(03)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drew D, Lerch M, Kunji E, Slotboom DJ, de Gier JW. Optimization of membrane protein overexpression and purification using GFP fusions. Nat Methods. 2006;3:303–313. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0406-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klepsch M, Schlegel S, Wickstrom D, Friso G, van Wijk KJ, Persson JO, de Gier JW, Wagner S. Immobilization of the first dimension in 2D blue native/SDS-PAGE allows the relative quantification of membrane proteomes. Methods. 2008;46:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelham HRB. The Retention Signal for Soluble Proteins of the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:483–486. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90303-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drew D, Slotboom DJ, Friso G, Reda T, Genevaux P, Rapp M, Meindl-Beinker NM, Lambert W, Lerch M, Daley DO, Van Wijk KJ, Hirst J, Kunji E, De Gier JW. A scalable, GFP-based pipeline for membrane protein overexpression screening and purification. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2011–2017. doi: 10.1110/ps.051466205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drew DE, von Heijne G, Nordlund P, de Gier JWL. Green fluorescent protein as an indicator to monitor membrane protein overexpression in Escherichia coli. FEBS Letters. 2001;507:220–224. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowhan W, Bogdanov M. Lipid-dependent membrane protein topogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:515–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.060806.091251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirai A, Matsuyama A, Yashiroda Y, Hashimoto A, Kawamura Y, Arai R, Komatsu Y, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Global analysis of gel mobility of proteins and its use in target identification. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10745–10752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rath A, Nadeau VG, Poulsen BE, Ng DP, Deber CM. Novel Hydrophobic Standards for Membrane Protein Molecular Weight Determinations via Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis. Biochemistry. 2011;49:10589–10591. doi: 10.1021/bi101840j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunji ER, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. Lactococcus lactis as host for overproduction of functional membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu LY, Link AJ. Stress responses to heterologous membrane protein expression in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 2009;31:1775–1782. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-0075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arsene F, Tomoyasu T, Bukau B. The heat shock response of Escherichia coli. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;55:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunsalus RP, Park SJ. Aerobic-anaerobic gene regulation in Escherichia coli: control by the ArcAB and Fnr regulons. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:437–450. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geertsma ER, Groeneveld M, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. Quality control of overexpressed membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5722–5727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802190105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.jNeuhoff V, Arold N, Taube D, Ehrhardt W. Improved staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels including isoelectric focusing gels with clear background at nanogram sensitivity using Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and R-250. Electrophoresis. 1988;9:255–262. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowie JU. Solving the membrane protein folding problem. Nature. 2005;438:581–589. doi: 10.1038/nature04395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck K, Eisner G, Trescher D, Dalbey RE, Brunner J, Muller M. YidC, an assembly site for polytopic Escherichia coli membrane proteins located in immediate proximity to the SecYE translocon and lipids. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:709–714. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner S, Pop OI, Haan GJ, Baars L, Koningstein G, Klepsch MM, Genevaux P, Luirink J, de Gier JW. Biogenesis of MalF and the MalFGK(2) maltose transport complex in Escherichia coli requires YidC. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17881–17890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadlish H, Pitonzo D, Johnson AE, Skach WR. Sequential triage of transmembrane segments by Sec61alpha during biogenesis of a native multispanning membrane protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:870–878. doi: 10.1038/nsmb994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steen A, Wiederhold E, Gandhi T, Breitling R, Slotboom DJ. Physiological adaptation of the bacterium Lactococcus lactis in response to the production of human CFTR. Mol Cell Proteomics. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000052-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skretas G, Georgiou G. Simple genetic selection protocol for isolation of overexpressed genes that enhance accumulation of membrane-integrated human G protein-coupled receptors in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 76:5852–5859. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00963-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Link AJ, Skretas G, Strauch EM, Chari NS, Georgiou G. Efficient production of membrane-integrated and detergent-soluble G protein-coupled receptors in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1857–1863. doi: 10.1110/ps.035980.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massey-Gendel E, Zhao A, Boulting G, Kim HY, Balamotis MA, Seligman LM, Nakamoto RK, Bowie JU. Genetic selection system for improving recombinant membrane protein expression in E. coli. Protein Sci. 2009;18:372–383. doi: 10.1002/pro.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giacalone MJ, Gentile AM, Lovitt BT, Berkley NL, Gunderson CW, Surber MW. Toxic protein expression in Escherichia coli using a rhamnose-based tightly regulated and tunable promoter system. Biotechniques. 2006;40:355–364. doi: 10.2144/000112112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y, Bowie JU. Building a thermostable membrane protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6975–6979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez Molina D, Cornvik T, Eshaghi S, Haeggstrom JZ, Nordlund P, Sabet MI. Engineering membrane protein overproduction in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2008;17:673–680. doi: 10.1110/ps.073242508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serrano-Vega MJ, Magnani F, Shibata Y, Tate CG. Conformational thermostabilization of the beta1-adrenergic receptor in a detergent-resistant form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:877–882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711253105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarkar CA, Dodevski I, Kenig M, Dudli S, Mohr A, Hermans E, Pluckthun A. Directed evolution of a G protein-coupled receptor for expression, stability, and binding selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14808–14813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803103105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnani F, Shibata Y, Serrano-Vega MJ, Tate CG. Coevolving stability and conformational homogeneity of the human adenosine A2a receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10744–10749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804396105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldo GS, Standish BM, Berendzen J, Terwilliger TC. Rapid protein-folding assay using green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:691–695. doi: 10.1038/10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baars L, Ytterberg AJ, Drew D, Wagner S, Thilo C, van Wijk KJ, de Gier JW. Defining the role of the Escherichia coli chaperone SecB using comparative proteomics. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10024–10034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marani P, Wagner S, Baars L, Genevaux P, de Gier JW, Nilsson I, Casadio R, von Heijne G. New Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins identified through prediction and experimental verification. Protein Sci. 2006;15:884–889. doi: 10.1110/ps.051889506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.