Abstract

Although lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide, the precise molecular mechanisms that give rise to lung cancer are incompletely understood. Here, we demonstrate that HMGA1 is an important oncogene that drives transformation in undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma. First, we show that the HMGA1 gene is overexpressed in lung cancer cell lines and primary human lung tumors. Forced overexpression of HMGA1 induces a transformed phenotype with anchorage-independent cell growth in cultured lung cells derived from normal tissue. Conversely, inhibiting HMGA1 expression blocks anchorage-independent cell growth in the H1299 metastatic, undifferentiated, large cell human lung carcinoma cells. We also demonstrate that the matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) gene is a downstream target up-regulated by HMGA1 in large cell carcinoma cells. In chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments, HMGA1 binds directly to the MMP-2 promoter in vivo in large cell lung cancer cells, but not in squamous cell carcinoma cells. In large cell carcinoma cell lines, there is a significant, positive correlation between HMGA1 and MMP-2 mRNA. Moreover, interfering with MMP-2 expression blocks anchorage-independent cell growth in H1299 large cell carcinoma cells, indicating that the HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway is required for this transformation phenotype in these cells. Blocking MMP-2 expression also inhibits migration and invasion in the H1299 large cell carcinoma cells. Our findings suggest an important role for MMP-2 in transformation mediated by HMGA1 in large cell, undifferentiated lung carcinoma and support the development of strategies to target this pathway in selected tumors.

Keywords: MMP-2, HMGA1, lung cancer, oncogene

Introduction

Lung cancer is a leading cause of cancer death worldwide and the incidence is rising, particularly in developing nations where smoking rate is increasing (1). Therapy is highly toxic and largely ineffective, leading to an overall 5-year survival of only 15% for all types of lung cancer (1). Based on histopathologic findings, lung cancer is classified as small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer. Small cell lung cancer constitutes 10-15% of all lung cancer and typically occurs in the setting of cigarette smoke exposure (1). Non-small cell lung cancer makes up the remaining 85-90% of lung cancers, and is further subdivided into: 1. squamous cell carcinoma (∼20-30% of all lung cancer cases), 2. adenocarcinoma (∼40% of all cases), and, 3. large cell, undifferentiated carcinoma (∼10-15% of all cases) (1). The molecular mechanisms that lead to small cell and non-small cell lung cancer have not been clearly elucidated.

To better understand how lung cancer develops, we are studying molecular pathways involved in transformation. Our focus is the HMGA1 gene, which encodes the HMGA1a and HMGA1b chromatin binding proteins. These protein isoforms result from alternatively spliced mRNA and differ by 11 internal amino acids present only in HMGA1a (2-8). The low-molecular weight (high mobility group) proteins contain AT hook DNA binding domains that enable HMGA1 proteins to bind to AT-rich regions of DNA (reviewed in ref. 6). Because they function in regulating gene expression and alter chromatin structure, HMGA1 proteins have been described as architectural transcription factors. HMGA1 expression is up-regulated in diverse human cancers (reviewed in ref. 7-8) and high levels of expression portend a poor prognosis in some tumors. More recent studies also demonstrate that HMGA1 has oncogenic properties in cultured cells (9-12) and transgenic mice (13-15). How this gene leads to neoplastic transformation is only beginning to be elucidated (8).

Matrix metalloproteinases are a family of over 20 extracellular, zinc-dependent proteolytic enzymes capable of degrading multiple components of the extracellular matrix (16-19). These enzymes play important roles in normal physiological conditions such as matrix homeostasis, but also in pathological processes including tumor progression where their expression is associated with invasive and metastatic behavior (16-19). A recent study also identified a matrix metalloproteinase with tumor suppressor function (20). Here, we show that HMGA1 activates MMP-2 expression in undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells. Moreover, the HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway is required for anchorage-independent cell growth, cellular invasion, and migration in metastatic, undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells. Taken together, these results support a critical role for MMP-2 in malignant transformation by HMGA1 and implicate this pathway as a rational therapeutic target in selected lung cancer patients with large cell carcinomas.

Results

HMGA1a is Overexpressed in Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines and Primary Lung Tumors

To determine if HMGA1 is overexpressed in human lung cancer, we initially surveyed human lung cancer cells lines for HMGA1 protein by Western analysis compared to cultured cells from normal lung tissue (Fig. 1A). We found that HMGA1 protein is increased in 5/5 lung cancer cell lines, including H1299 metastatic, large cell (undifferentiated), lung carcinoma cells (21), SK-MES-1 metastatic, squamous cell carcinoma cells (22), H358 nonmetastatic, bronchioalveolar carcinoma cells (23-24), H125 metastatic adenosquamous carcinoma cell line (22), and H82 metastatic small cell lung cancer cell line (25). These lung cancer cells were compared to the control BEAS-2B cells (26), which are cultured, immortalized cells isolated from normal human lung bronchial epithelium. We also assessed HMGA1a mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR compared to normal lung tissue RNA (Clontech) from pooled, control individuals (Fig. 1 B). We included three metastatic, undifferentiated, large-cell carcinoma cell lines (H1299, H460, H661, ref. 21, 27-28), two metastatic squamous cell carcinoma cell line (SK-MES, U-1752; ref 22, 29), one metastatic adenosquamous carcinoma cell line (H125; ref. 22), and one metastatic, small cell carcinoma cell line (H82; ref. 25). Notably, HMGA1a mRNA was also increased in all the lung cancer cells tested compared to the controls (Fig. 1A). To determine if gene amplification could account for the HMGA1 overexpression, we performed Southern analysis in the H1299, H460, and H661 large cell carcinoma cells compared to DNA from normal human lymphocytes. There was no evidence for amplification (Supplementary Fig 1). In addition, sequence analysis of the HMGA1a and HMGA1b coding regions in the large cell carcinoma cell lines showed no mutations (not shown).

FIGURE 1.

HMGA1 is overexpressed in cultured human lung cancer cells and primary lung tumors.

A. HMGA1 protein is increased in the cultured human lung cancer cell lines: H1299, SK-MES-1, H358, H125, and H82 compared to the control BEAS-2B cells derived from normal human bronchial lung.

B. HMGA1a mRNA is increased in the cultured human human lung cancer cell lines: H1299, H460, H661, H125, U1752, SK-MES-1, and H82 compared to RNA from pooled, normal lung tissue from normal individuals.

C. HMGA1a mRNA is increased in 71% of primary lung cancer tumors by qRT-PCR. C, Control RNA from normal lung derived from 3 normal individuals who died from causes other than lung cancer. Samples 1-15 are from primary lung tumors diagnosed histopathologically as adenocarcinoma and samples 16-24 are from primary lung tumors diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. The bottom panel shows tumor grade, stage, and lymph node metastases (+) if present. Additional clinical data is available in Supplementary Table S1.

D. HMGA1 mRNA is elevated in this case of adenocarcinoma by in situ hybridization.

To determine if HMGA1a expression is also increased in primary human lung tumors, we assessed HMGA1a mRNA levels by quantitative, reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). Pooled RNA from normal lungs was included as the control. We found that HMGA1a was overexpressed by ≥ 1.5-fold in 17/24 or 71% of all tumor samples compared to the normal lung tissue (Fig. 1C). There was HMGA1a overexpression in 11/15 (73.4%) of adenocarcinoma cases and 8/9 (88.9%) of squamous cell carcinoma cases. There was a history of exposure to cigarette smoke in 15/24 (63%) of these patients and it is possible that the smoke carcinogens induced aberrant gene expression in the lung tissue that preceded the development of the tumors. To further assess HMGA1 expression in human lung cancer, we performed in situ hybridization on a section from an adenocarcinoma with an antisense HMGA1 probe and observed significant HMGA1a mRNA staining in the malignant tumor, but not the adjacent, normal tissue (Fig. 1D). The control sense probe showed no staining (not shown). In four primary lung tumors with overexpression of HMGA1, there was sufficient sample for Western analysis, and HMGA1 protein was also elevated in these cases compared to normal lung tissue (not shown.)

Inhibiting HMGA1 Expression Blocks Transformation in Large Cell Lung Carcinoma Cells

To determine if HMGA1 is required for transformation in the human lung cancer cells, HMGA1 gene expression was inhibited in the H1299 metastatic, undifferentiated, large cell lung carcinoma cell line using an RNA interference approach (9, 11). We constructed an HMGA1 ribozyme antisense vector with antisense sequence directed at the amino-terminus (HMGA1-AS-1) (9) and the carboxyl-terminus (HMGA1-AS-2) (11). The H1299 lung cancer cells were transfected with each construct in separate transfection experiments and polyclonal cell lines were isolated. Both antisense cell lines had significantly decreased HMGA1 protein compared to the control cell line transfected with the vector alone (Fig. 2A). The loading control protein, β-actin, was unaffected by the antisense construct. In the antisense and control cell lines, the related protein, HMGA2, was also unaffected (Fig. 2A), indicating that the antisense vectors cause a specific, significant decrease in HMGA1 proteins.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibiting HMGA1 expression blocks transformation in cultured human lung cancer cells derived from metastatic disease.

A. Western analysis shows decreased HMGA1 protein in the antisense cell lines. The lane marked HMGA1-AS-1 represents H1299 polyclonal cells transfected with the amino-terminal antisense HMGA1 construct, the lane marked HMGA1-AS-2 represents H1299 polyclonal cells transfected with the carboxyl-terminal antisense construct, and the lane marked vector control represents H1299 polyclonal cells transfected with control vector alone. The blot was probed with the HMGA1 antibody as well as an antibody to β-actin to control for protein loading. Western analysis of HMGA2 protein in the control and antisense cell lines shows no decrease in HMGA2 protein. This blot was also probed with a β-actin antibody as a loading control.

B. Decreased anchorage-independent cell growth or foci formation in cells with decreased HMGA1 proteins (bar, 100 μm).

C. Graphical representation of decreased foci formation in the cells with decreased HMGA1 proteins. (p = 0.0000995 for HMGA1-AS-1 and p = 0.0000531 for HMGA1-AS-2; student's t-test). This experiment was performed 3 times in duplicate and results are expressed as the average (bar) +/- the standard deviation.

D. Cell growth rates in control cells and cells with decreased HMGA1 proteins were similar. This experiment was repeated 2 times and results are expressed as the average (bar) +/- the standard deviation.

The antisense cell lines with decreased HMGA1 proteins were subsequently analyzed in the soft agar assay to determine if transformation was inhibited in these cells. We observed that transformation was significantly blocked in both antisense cell lines by about 65-75% (p = 0.0000995 for HMGA1-AS-1; p = 0.0000531 for HMGA1-AS-2; student's t-test) compared to the polyclonal cell line transfected with control ribozyme vector (Fig. 2B-C). These results suggest that HMGA1 is critical for anchorage-independent cell growth in these cells. Cellular growth rates in the antisense and control cell lines were similar (Fig. 2D), indicating that transformation was blocked through a transformation-specific mechanism independent of decreased growth rate.

HMGA1a Induces a Transformed Phenotype with Anchorage-Independent Cell Growth in Lung Cells Derived from Normal Tissue

Because HMGA1a is overexpressed in lung cancer cell lines and inhibiting HMGA1a expression blocks transformation in H1299 large cell lung carcinoma cells, we hypothesized that HMGA1a induces neoplastic transformation in lung cells. To explore this hypothesis, we constructed a polyclonal cell line overexpressing HMGA1a in BEAS-2B (25) immortalized, normal lung bronchial epithelial cells. Western analysis of the lung cells transfected with the HMGA1a plasmid express high levels of the HMGA1a protein compared to the control cells transfected with pSG5 control vector alone (Fig. 3A). We observed that BEAS-2B cells overexpressing HMGA1a formed transformed colonies capable of anchorage-independent growth (or foci formation) in soft agar in a manner similar to H1299 large cell lung carcinoma cells (Fig. 3B). To determine if the transfected lung cell lines grow similarly in tissue culture, we performed growth curves for all stable cell lines. All cell lines grew at a similar rate, indicating that the transformed phenotype was not a result of an increased growth rate (Fig. 3C). Thus, our results show that HMGA1a has similar transforming activity in the cultured lung cells derived from normal lung tissue, indicating that it is oncogenic in these cells. Moreover, the knock-down experiments in H1299 large cell carcinoma cells indicate that HMGA1 is required for the transformed phenotype observed in these lung cancer cells.

FIGURE 3.

HMGA1a induces a transformed phenotype with anchorage-independent cell growth in cultured cells derived from normal, human lung tissue.

A. BEAS2-B cells transfected with the HMGA1a vector overexpress the HMGA1a protein compared to cells transfected with control, empty vector by Western analysis. Membranes were blotted with the HMGA1 antibody as well as a β-actin antibody to control for sample loading.

B. Lung cells overexpressing HMGA1 exhibit anchorage-independent cell growth (foci formation) in soft agar. Results are expressed as the average (bar) +/- the standard deviations from 2 different experiments performed in duplicate. A representative plate from each condition is shown.

C. Cell growth rates of the transfected BEAS-2B cell lines. This experiment was performed with duplicate plates and repeated twice. The error bars depict the standard deviations from a representative experiment.

HMGA1 Binds Directly to the MMP-2 Promoter in Undifferentiated, Large Cell Carcinoma Lung Cancer Cells in vivo

Because HMGA1 functions in regulating gene expression, it has been postulated that it induces neoplastic transformation by altering expression of critical target genes involved in cell growth and transformation (7-8). The gene targets that mediate transformation by HMGA1, however, are only beginning to be elucidated (8). We previously identified the gene encoding matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2, matrix metalloproteinase-2, or gelatinase A) as a candidate HMGA1a target gene up-regulated in prostate cancer cells (30). Because MMP-2 has also been implicated in both tumor invasiveness and neoplastic disease of the lung (16-19), we investigated its potential role in lung cancers overexpressing HMGA1. To determine if HMGA1 could bind directly to the MMP-2 promoter, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments in the H1299 metastatic, undifferentiated large cell lung carcinoma cells. We found that HMGA1 binds to the MMP-2 promoter in a highly conserved region near the transcription start sites (Fig. 4A; ref. 31). This region includes two conserved, predicted HMGA1 consensus DNA binding sites within 200 nucleotides upstream of the two transcription start sites (31). In primary human BJ fibroblasts transduced to overexpress HMGA1a, we also found that MMP-2 expression is significantly increased (p = 0.00001; not shown). These findings suggest that HMGA1 binds to the MMP-2 promoter to up-regulate its expression.

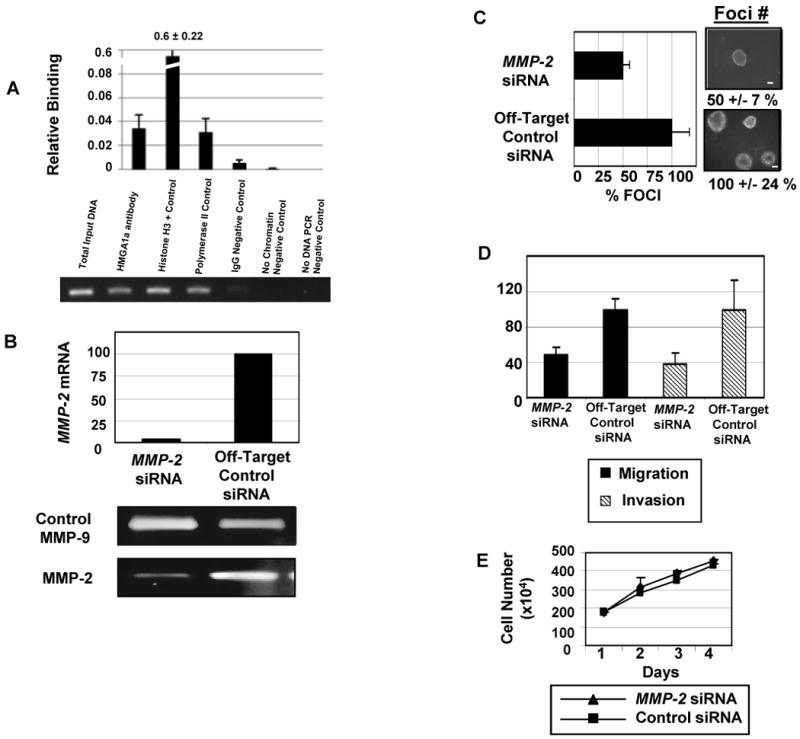

FIGURE 4.

The HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway contributes to anchorage-independent cell growth, migration, and invasion in metastatic lung cancer cells.

A. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with sheared chromatin from H1299 cells after cross-linking proteins bound to DNA with formaldehyde (15). The graph shows the quantity of immunoprecipitated DNA (bars) +/- the standard deviations with the following antibodies (all from Upstate, except for the HMGA1 antibody): HMGA1 (35), Polymerase II (Pol II or histone H3, both as positive controls), or rabbit IgG (as a negative control). Additional negative controls included no chromatin and no DNA. The HPRT promoter sequence was also used as a negative control because there are no HMGA1 DNA-binding sites in the region amplified and previous chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments showed no binding by HMGA1 to the amplified region (15, 35). The gel shows total input DNA compared with the DNA immunoprecipitated with the same antibodies.

B. MMP-2 mRNA and protein are decreased in the H1299 cells transfected with siRNA to MMP-2 (20 nmol/L; Dharmacon) compared with cells transfected with the off-target control siRNA (siCONTROL nontargeting siRNA pool at 20 nmol/L; Dharmacon). The mRNA levels for MMP-2 and control β-actin (β-actin primer/probe set; Applied Biosystems) were assessed at 24 h, 48 h, 8 days, and 10 days after adding the siRNA. MMP-2 mRNA was normalized to β-actin as the loading control. MMP-2 mRNA was decreased at all time points; only the day 8 time point is shown here. (See Supplementary Figure 1 for the remaining time points.) All standard deviations were less than 5%. Protein was assessed for secreted MMP-2 by zymography at the same time points as the mRNA. The MMP-9 protein was also measured as a loading control. The zymogram shows decreased MMP-2 protein at 8 days; see Supplemental Figure 1 for the remaining time points.

C. Anchorage-independent cell growth or foci formation are decreased in the H1299 cells with knock-down in MMP-2 expression. The bar graph shows the decreased number of foci in the cells incubated with siRNA to MMP-2 compared with the control siRNA. The bars represent the mean +/- the standard deviations from three experiments done in triplicate (100% +/- 41 % versus 49 % +/- 19 %; p =0.0019; student's t-test). The photograph shows actual foci from the experiment (bar, 100 μm).

D. Migration and invasion were also assessed in the H1299 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells with and without MMP-2 knock-down. Twenty-four hours after transfection with the siRNA, 3 × 104 cells/well were seeded onto the wells for migration/invasion insert. After 48 h, inserts were stained and counted for cells that migrated or invaded. There was a significant decrease in migration (p < 0.0001; student's t-test) and invasion (p = 0.0006; student's t-test). All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least once.

E. Growth curves showed that cells incubated with siRNA to MMP-2 or control siRNA proliferate at similar rates.

To determine if HMGA1 occupies the MMP-2 promoter in other large cell carcinoma cells, we investigated two additional cell lines: H661 and H460 (Supplementary Fig. 2). As with the H1299 cells, we found significant HMGA1 binding to the MMP-2 promoter in vivo in these undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells. In contrast, we did not observe HMGA1 binding to the MMP-2 promoter in neither U-1752 nor SK-MES squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings suggest that the HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway is up-regulated in the undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells.

MMP-2 is Necessary for Anchorage-Independent Cell Growth, Cellular Migration, and Invasion in H1299 Large Cell Carcinoma Lung Cancer Cells

To determine if MMP-2 is necessary for transformation in large cell carcinoma cells overexpressing HMGA1, we performed RNA interference experiments to knock-down expression of MMP-2 in H1299 lung cancer cells. Using siRNA (Dharmacon), we generated H1299 cells with effective knock-down of MMP-2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 4B-C, Supplementary Fig. 3). The cells with decreased MMP-2 expression had decreased foci formation by 50% (p = 0.019; student's t-test; Fig. 4D). Because MMP-2 is involved in degrading the extracellular matrix and thought to contribute to metastatic potential in some tumors, we also assessed migration and invasion in the H1299 lung cancer cells with and without MMP-2 knock-down. We found that migration was decreased by 51% (p = 0.001; student's t-test; Fig. 4E) and invasion was decreased by 63% (p = 0.0001; student's t-test; Fig. 4E). The cellular proliferation was similar for lung cancer cells treated with the MMP-2 or control siRNA (Fig. 4F). Taken together, our studies indicate that MMP-2 is a critical HMGA1 downstream target required for multiple transformation phenotypes, including anchorage-independent cell growth, migration, and invasion in H1299 human lung cancer cells.

HMGA1 and MMP-2 mRNA is Positively Correlated in Cultured, Large Cell Carcinoma Cells

Because we found that HMGA1 binds to the MMP-2 promoter in the undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells, we sought to determine if HMGA1a and MMP-2 expression correlate in this subset of lung cancer cells. To this end, we assessed the expression of HMGA1a and MMP-2 mRNA in the large cell carcinoma cell lines (H1299, H460, H661) by quantitative RT-PCR. Using Pearson's correlation, we found a highly significant positive correlation between HMGA1a and MMP-2 mRNA in these undifferentiated lung carcinoma cells (r = 0.96, p < 0.00001; Supplementary Fig. 4). In the contrast, there was only a weak correlation between HMGA1a and MMP-2 expression in the squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (U-1752, SK-MES; r = 0.59, p = 0.045; not shown). To assess HMGA1a and MMP-2 expression in primary tumors, we used data from the GSE2109 public microarray database, which included only 5 cases of primary large cell carcinomas. This was the largest number of large cell carcinoma primary tumors available from a published microarray study, which reflects the relatively low frequency of this tumor type. Using the Affymetrix probes directed at the 3′ UTR (206074_s_at for HMGA1, and 201069_at for MMP-2), there was no significant correlation between HMGA1a and MMP-2 expression by Pearson's correlation using the bootstrap method (32) in this very small sample size.

Although larger studies are needed to determine if the HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway is up-regulated in primary large cell lung tumors, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that HMGA1 drives tumorigenesis in large cell lung carcinoma, at least in part, by up-regulating MMP-2. We found a significant, positive correlation between HMGA1a and MMP-2 expression in undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells. In addition, HMGA1 occupies the MMP-2 promoter in vivo in these cells. Moreover, our functional studies demonstrate that HMGA1 and MMP-2 are required for anchorage-independent cell growth in large cell carcinoma cells. Taken together, these studies also suggest that the HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway could be targeted in “personalized therapy” for selected patients with large cell lung cancers characterized by dysregulation of this pathway.

Discussion

Lung cancer is a leading cause of death that continues to elude successful treatment in most patients. Each year, almost 200,000 new cases of lung cancer are diagnosed and over 150,000 people will die from this disease in the United States alone (1). Thus, research is urgently needed to discover molecular targets that could be exploited in therapy (1). Although progress has been made in understanding some of the molecular aberrations that lead to lung cancer, this has not translated into better therapy or improved survival (33-34).

Because the HMGA1 gene is up-regulated in malignant transformation (7-8), we investigated its role in lung cancer. Here, we show that HMGA1a is overexpressed in all metastatic human lung cancer cell lines and most primary tumors. Another recent study showed high levels of HMGA1 expression in human lung cancer primarily by immunohistochemical analysis, including moderate to strong staining for HMGA1 in 8/9 large cell carcinomas (35). Further, they found a correlation between HMGA1 staining and poor survival, although they did not determine if there was a relationship between HMGA1 staining and differentiation status or tumor grade in this study. Here, we demonstrate a functional role for HMGA1 in lung carcinogenesis. Specifically, we found that HMGA1a induces a transformed phenotype in lung cells derived from normal lung tissue and inhibiting its expression blocks anchorage-independent cell growth in metastatic, large cell carcinoma lung cancer cells. Although additional studies with animal models are warranted, these results suggest that blocking HMGA1 function could have therapeutic implications for lung cancer. Of note, another group used an HMGA1 antisense approach in other cancer cell lines and observed both apoptosis and decreased proliferation (36). We did not observe a significant decrease in growth rates in the H1299 cells with knock-down of HMGA1, suggesting that inhibition of transformation was independent of proliferation or apoptosis. Regardless of the mechanisms involved, decreasing HMGA1 proteins interferes with transformation in several malignant cell lines, suggesting that it could serve as a therapeutic target.

HMGA1 is widely overexpressed in aggressive human cancers, which underscores the importance of elucidating the molecular mechanisms that drive HMGA1a-mediated tumorigenesis (7-8). Because HMGA1 functions in transcriptional regulation, it has been postulated that it induces transformation by dysregulating specific gene targets (7-8, 12, 15, 30, 37). The repertoire of target genes regulated by HMGA1, however, is only beginning to emerge and is likely to depend upon the cellular milieu. We previously showed that HMGA1a up-regulates MMP-2 in prostate cancer cells (30), although the role of MMP-2 in transformation mediated by HMGA1 was not explored. A previous study demonstrated that MMP-2 protein expression predicts an unfavorable outcome with decreased survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (38). In addition, MMP-2 has been implicated in tumor invasiveness in lung cancer (16-17). Thus, we investigated the functional significance of the HMGA1-MMP-2 pathway in lung cancer. Interestingly, we found a highly significant, positive correlation between HMGA1a and MMP-2 mRNA in the undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells. Moreover, our chromatin-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate that HMGA1 binds directly to the MMP-2 promoter in all three undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cell lines studied. In addition, inhibiting MMP-2 expression blocks anchorage-independent cell growth, migration, and invasion in undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma cells. We recently reported a similar correlation between HMGA1 protein levels and poor differentiation status in pancreatic cancer (39). Another group also identified HMGA1 as a key transcription factor in embryonic stem cells and undifferentiated or high-grade breast, bladder, and brain cancer, further implicating HMGA1 in driving tumor progression and a primitive, undifferentiated state in normal stem cells and cancer (40).

The MMPs family of zinc-dependent proteinases was originally characterized based on these proteinases ability to degrade extracellular matrix and basement membrane proteins (16-19). By degrading the basement membrane, MMPs are thought to enhance cell mobility in a stationary tumor cell and promote metastases. In fact, MMP activity correlates with cellular invasiveness and metastatic potential in some solid tumors (16-19). More recently, MMPs were shown to exert other important biologic effects relevant to cancer by cleaving critical proteins involved in angiogenesis, apoptosis, chemotaxis, cell migration, and cell proliferation (16). Thus, it has become clear that MMPs not only function in cancer progression and metastasis, but may also contribute to steps of cancer development (16-19). These diverse activities may account for the role of MMP-2 in mediating anchorage-independent cell growth, migration, and invasion observed in our studies. Another group recently showed that HMGA1 may modulate MMP-9 activity in pancreatic cancer (41) and putative HMGA1 DNA binding sites are present in the promoter regions of several MMP family members (Resar, unpublished data). This suggests that HMGA1 could promote metastatic progression by orchestrating the activity of varied MMP genes, depending upon the cellular context. Along these lines, a recent study also found that MMP-2 immunostaining is a more sensitive predictor than MMP-9 in lung cancer progression, metastasis, and survival (42).

In conclusion, we discovered that HMGA1 is an important oncogene that appears to drive transformation in human lung cancer. Moreover, we show that MMP-2 is a critical downstream target activated by HMGA1 in undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma lung cancers. Our findings identify a molecular mechanism for increased MMP-2 expression and implicate this pathway as a rational therapeutic target in selected cases of lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transfection

BEAS-2B (26), H1299 (21), SK-MES-1 (22), H358 (23-24), H125 (22), H82 (25), H460 (27), and H661 (28) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown according to ATCC guidelines. U-1752 (29) were grown as previously described (48). Cells were transfected using Lipofectin as described by the manufacturer (GIBCO/BRL). Polyclonal, pooled, resistant cell lines overexpressing HMGA1a or control vector were selected in media containing puromycin (0.75 ug/ml). H1299 cells transfected with the HMGA1 (HMG-I) ribozyme antisense (9, 11) and control constructs were selected in media containing Zeocin (75 ug/ml). Polyclonal, pooled, resistant cell lines with decreased HMGA1 proteins by Western analysis were used for soft agar analysis. H1299 cells were transfected with siRNA (Dharmacon) according to manufacturer's instructions as we previously described (12, 15).

Plasmids

The HMGA1 antisense constructs were previously described (9, 11). Briefly, both vectors were made using the vector pU1/RIBOZYME, which incorporates an autocatalytic hammerhead ribozyme structure within the complementary sequence. The NT-antisense-HMGA1 vector included antisense sequence directed at the amino-terminus (AS-1) and the CT-antisense-HMGA1 vector (AS-2) included antisense sequence directed at the carboxyl-terminus (11). The parent vector pU1/RIBOZYME was used as a control vector for both antisense vectors.

The plasmids pSG5-HMGA1a and pSG5-HMGA1b have been previously described (9-10).

Western Analysis

For Western blot analysis of HMGA1, total cell lysates collected from growing cells were boiled in 2× Laemmli buffer and analyzed by SDS/4-20% gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and subjected to Western analysis using a chicken polyclonal antibody raised against the amino-terminus of HMGA1 diluted 1:500 as described previously (9-10). For analysis of HMGA2, a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the amino-terminus of HMGA2 was diluted 1:500 (9-10). The actin monoclonal antibody AC15 (Sigma Immunochemicals) was diluted 1:5,000 and used to control for sample loading. Reactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham).

In situ Hybridization

To assess HMGA1 gene expression in lung cancer specimens, in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (43).

Riboprobe Preparation for Nonradioactive in situ Hybridization

PCR was used to generate 400-500-bp sized DNA templates for antisense or sense riboprobes by incorporating the T7 promoter into the 5′ end of the antisense or sense primer as described (43). The primers for HMGA1 were: Forward-5′ GAA GGG AAG ATG AGT GAG TCG AGC TCG 3′, and, Reverse-5′ GGT AAA TCT GCT CCT CAC TCA GCC C 3′. The primers incorporating T7 for HMGA1 were: Forward-5′ CTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG AAG CGA AGA TGA C 3′, and Reverse-5′ CTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG GGT AAA TCT GCT C 3′.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Experiments

Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as we previously described (15) using H1299 cells. Proteins cross-linked to chromatin were immunoprecipitated with the following antibodies: HMGA1 (12, 15, 44), Pol II or histone H3 (as positive controls), or IgG (as a negative control). The MMP-2 promoter region with the consensus HMGA1 DNA-binding site was amplified from the immunoprecipitated protein-DNA complexes using the forward and reverse primers 5′-GGG GAA AAG AGG TGG AGA AA-3′ and 5′-CGC CTG AGG AAG TCT GGA T-3′, respectively. The HPRT1 promoter was amplified as a negative control promoter with no HMGA1 binding sites as described (12, 15, 44).

MMP-2 Knock-Down Experiments

Small interfering RNA was used to knock down expression of MMP-2 according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Specifically, the H1299 cells were incubated with siRNA to MMP-2 (20 μmol/L; Dharmacon) compared with the control siRNA (20 μmol/L; siCONTROL non targeting siRNA pool which contains four negative control siRNAs without matches to human, mouse, or rat gene also by Dharmacon). After 18 to 20 h of incubation, cells were washed and placed in soft agar or maintained in culture dishes to harvest for protein or mRNA at the indicated time points. Protein levels for MMP-2 were assessed by gelatin zymography with conditioned media at 24 h, 48 h, 8 d, and 10 d after transfection with each siRNA. MMP-2 and control β-actin mRNA levels were assessed at the same time points.

Gelatin Zymography of Conditioned Media

Media was collected and subjected to gelatin zymography as previously described (45-46). Further identification of the matrix metalloproteinases was performed using low molecular weight protease inhibitors added to the Triton X-100 buffer during the 2 days of incubation required for protease activation as previously described (45-46).

Soft Agar Assay

Soft agar assays were performed as previously described (9-10), but with the following exceptions. For the BEAS-2B cells, 2×105 cells were seeded in 8 ml of top agarose comprised of 1.2 ml of 2% agarose and 6.8 ml of BEGM medium and layered on top of 10 ml of bottom agarose comprised of 2.5 ml of 2% agarose and 7.5 ml of BEGM medium (Clonetics CC-3170). For the H1299 experiments, 2× RPMI containing 5%FBS was used instead of 2× DMEM. To determine the effects of MMP-2 knock-down, H1299 cells were transfected with siRNA to MMP-2 or control siRNA and 5,000 cells/ml in suspension were mixed with 0.4 % agarose-RPMI supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum. Cells were then seeded on a 0.8 % agarose base. Colony growth was assayed two weeks later by counting colonies under the microscope. Experiments were done in triplicate and repeated at least once.

Cellular Growth Rate Determinations

The growth rates of the BEAS-2B and H1299 lung cells were determined as previously described (9-10). Cells were seeded at 2×105 into 6 separate 10 cm tissue culture dishes. Duplicate dishes were harvested every 24 h for 3 days and the cells were counted. For the MMP-2 knock-down experiments, cell proliferation was evaluated at 24 h intervals by measuring the mitochondrial-dependent conversion of the tetrazolium salt, MTS, to a colored formazan product using a CellTiter 96 AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well and grown for one week. A volume of 20μl of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent was pipeted directly into each well of the 96-well assay plate containing cells in 100μl of culture medium and cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. Optical density was read at 490nm using a 96-well microplate reader (Mode 680, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Migration and Invasion Assays

Migration and invasion assays were performed in 24-well plates containing 0.8 um pores cell culture inserts with polyethylene terephthalate membranes according to manufacturer's instructions (BioCoat Cell Culture Inserts, BD Biosciences) as previously described (47). Briefly, for invasion, filters were coated with 100 μl growth factor-reduced Matrigel at 0.5 to 0.8 mg/ml protein on ice. For migration, the experiment was identical except that the filters were not coated with Matrigel. The cells were seeded in 500 μl of 10 % FBS-RPMI at 30,000 cells per well into the upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled with 750 μl of the same medium. After 48 h, migration or invasion was assessed by counting cells on the underside after fixation with 70% ethanol and staining with hematoxylin as described (47).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR Analysis

Cells were stored in RLT buffer (Qiagen) and tissues were stored in TRIzol at -80° C, and total RNA was subsequently extracted from cell lines and tumors as we described (13, 15). RNA (10 ng) and HMGA1 primers used for PCR were previously described (13, 15). For MMP-2, commercially available primers and probe set were used (Applied Biosystems). For control RNA from normal lung, we used commercially available RNA (Clontech) harvested from lung tissue from three normal individuals (ages 19-50 years) who died with no history of lung disease or lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Southern Blot analysis was performed with ECL detection using a commercial kit (Amersham ECL Direct Nucleic Acid Labeling and Detection System) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was incubated at 37°C overnight with the restriction enzyme, EcoRI (New England Biolabs; 2 units/μg of DNA/10μl reaction volume), as we previously described13. PCR was used to generate a 312 base pair HMGA1a DNA probe using pET7C as template49. The primers were: forward-5′ CTC GAA GTC CAG CCA GCC CTT 3′, and, reverse-5′ GGT CAC TGC TCC TCC TCC GA 3′. The expected bands (arrows) show similar intensity in all 3 large cell carcinoma cell lines (H1299, H460, H661) compared to the control BEAS-2B cells and normal human DNA from lymphocytes, indicating no HMGA1 gene amplification in these cells.

Sequence analysis for HMGA1a mutations. To determine if the HMGA1 coding region was mutated in the large cell lung carcinoma cells, PCR was used to generate 171 and 208 base pair overlapping HMGA1a fragments from cDNA prepared as previously described15. The 171 base pair fragment extends from nucleotide 290 to 460 (based on reference sequence NM_145899.2) and was generated using the following primers: forward-5 ′TCA CTC TTC CAC CTG CTC CT 3′ and reverse-5 ′CTT CTG ACT CCC TAC CAG CG 3′. The 208 base pair fragment extends from nucleotide 448 to 648 and was generated using the following primers: forward-5′ CGC TGG TAG GGA GTC AGA AG 3′ and reverse-5′ GGT CAC TGC TCC TCC TCC GA 3′. Nucleotide sequencing of the PCR fragments was performed by the Johns Hopkins University Core DNA Analysis Facility by one-capillary cycle sequencing using the Applied Biosystems 3730×l DNA Analyzer (Sanger-based). There were no mutations detected in the HMGA1a coding regions in the large cell carcinoma cell lines (H1299, H460, H661).

Supplementary Fig. 2. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with sheared chromatin from different lung cancer cells after cross-linking proteins bound to DNA with formaldehyde (15). As shown in Fig. 4, the graphs indicate the relative quantity of immunoprecipitated DNA (bars) +/- the standard deviations with the following antibodies (all from Upstate, except for the HMGA1 antibody): HMGA1 (15), Polymerase II (Pol II) or histone H3, (both as positive controls), and rabbit IgG (as a negative control). Additional negative controls included no chromatin and no DNA. There is significant in vivo binding of HMGA1 to the MMP-2 promoter in the metastatic, large cell lung carcinoma cells (H661 and H460), but no significant binding in the metastatic, squamous cell carcinoma cells (U-1752 and SK-MES).

Supplementary Fig. 3. MMP-2 protein and mRNA are decreased in the H1299 cells transfected with siRNA to MMP-2 (20 nmol/L; Dharmacon) compared with cells transfected with the off-target control siRNA (siCONTROL nontargeting siRNA pool at 20 nmol/L; Dharmacon). Secreted MMP-2 and control MMP-9 protein activity were assayed by zymography at 24 h, 48 h, 8 days, and 10 days after adding the siRNA. The mRNA levels for MMP-2 and control β-actin (β-actin primer/probe set; Applied Biosystems) were assessed at the same time points. MMP-2 mRNA was normalized to β-actin as the loading control. Standard deviations for qRT-PCR were all less than 5%.

Supplementary Fig. 4. HMGA1 and MMP-2 mRNA are highly correlated in the undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma lung cancer cell lines; r = 0.96, p < 0.00001 by Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Table S1. Histologic Type and Clinical Characteristics

Table 1. HMGA2 expression by Histologic Type and Clinical Characteristics in tissue microarray.

| Histologic Type* | Age, years (mean +/- SD) |

Gender M/F |

Smoking Historyˆ | Stage | Death before 5 years | HMGA2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | <3 | 3 to 6 | >6 | |||||

| AC (n = 29) | 66.3 +/-11.4 | 9/20 | 22/25 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 24 | 4 | 1 |

| SCC (n = 30) | 68.1 +/- 8.0 | 25/5 | 25/27 | 18 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 12 | 10 | 8 |

| BAL (n = 8) | 66.4 +/- 9.7 | 2/6 | 5/6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| CA, NOS (n = 8) | 66.3 +/- 8.4 | 4/4 | 7/7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Carcinoid (n = 3) | 61.3 +/-17.1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| LCLC (n = 2) | 76.5 +/- 5.0 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| AGC (n = 1) | 68 | 1/0 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PSC (n = 1) | 63 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SCLC (n = 3) | 64 +/- 3.0 | 2/1 | 3/3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Undiff (n = 3) | 60 +/- 13.1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

AC – adenocarcinoma; SCC – squamous cell carcinoma; BAL – bronchoalveolar carcinoma; CA, NOS – Carcinoma, not otherwise specified; LCLC – large cell lung cancer, AGC – anaplastic giant cell carcinoma; PSC – pleomorphic sarcomatoid carcinoma; SCLC – small cell lung carcinoma; Undiff – undifferentiated carcinoma

Smoking history where available

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Edward Gabrielson and the Johns Hopkins Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Lung Cancer (NIH P50 CA058184) for providing the primary lung tumor specimens. We also apologize to the many authors whose important work could not be cited here due to space limitations.

Grant Support: NIH RO1, The American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Scholar Award 1694-06 (L.M. S. Resar), Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation Award (L.M. S. Resar and J. Hillion) the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (L. M. S. Resar, J. Hillion, B. Joseph, and A. Belton), The Gynecologic Cancer Foundation, Prevent Cancer Foundation (J. Hillion), the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institution (F. Di Cello and R. Bhattacharya), and NIH T32 (L. Wood. M. Mukherjee, R. Bhattacharya, and A. Belton).

Abbreviations

- HMGA1a

high mobility group A1 gene

- RT-PCR

real time polymerase chain reaction

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase-2

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. 2007 www.cancer.org.

- 2.Lund T, Holtlund J, Fredriksen M, Laland SG. On the presence of two new high mobility group-like proteins in HeLa S3 cells. FEBS Lett. 1983;152:163–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustin M, Lehn DA, Landsman D. Structural features of the HMG chromosomal proteins and their genes. Biochemica ET Biophysica Acta. 1990;1049:231–43. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90092-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson KR, Cook SA, Davisson MT. Chromosomal localization of the murine gene and 2 related sequences encoding high-mobility group I and Y proteins. Genomics. 1992;12:503–9. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90441-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedmann M, Holth LT, Zoghbi HY, Reeves R. Organization, inducible expression and chromosomal localization of the human HMG-I (Y) nonhistone protein gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4259–67. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.18.4259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustin M. Regulation of DNA-dependent activities by the functional motifs of the high-mobility-group chromosomal proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5237–46. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves R. Molecular biology of HMGA proteins: Molecular biology of HMGA proteins: hubs of nuclear function. Gene. 2002;277:63–81. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fusco A, Fedele M. Roles of HMGA proteins in cancer. Nature reviews. 2007 Dec;7(12):899–910. doi: 10.1038/nrc2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood LJ, Mukherjee M, Dolde CE, et al. HMG-I/Y: A new c-Myc target gene and potential oncogene. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5409–502. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5490-5502.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood LJ, Maher JF, Bunton TE, Resar LMS. The oncogenic properties of the HMG-I gene family. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4256–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolde C, Mukherjee M, Cho C, Resar LMS. HMG-I/Y in human breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;71:181–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1014444114804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillion J, Dhara S, Sumter TF, et al. The HMGA1a-STAT3 axis: an “Achilles heel” for hematopoietic malignancies? Cancer Res. 2008;68:10121–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Sumter Felder T, Bhattacharya R, et al. The HMG-I oncogene causes highly penetrant, metastatic lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice and is overexpressed in human lymphoid malignancy. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3371–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedele M, Pentimalli F, Baldassarre G, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing the wild-type form of the HMGA1 gene develop mixed growth hormone/prolactin cell pituitary adenomas and natural killer cell lymphomas. Cancer Res. 2005;24:3427–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tesfaye A, Di Cello F, Hillion J, et al. HMGA1a Up-regulates Cox-2 in uterine tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3998–4004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker S, Cao J, Chen WT. Critical appraisal of the use of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer treatments. Oncogene. 2000;19:6642–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-cancer targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:227–38. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy MJ, McGowan PM, Gallagher WM. Cancer invasion and metastasis: changing views. J Pathol. 2008;214:283–93. doi: 10.1002/path.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palavalli LH, Prickett TD, Wunderlich JR, et al. Analysis of the matrix metalloproteinase family reveals that MMP8 is often mutated in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:518–20. doi: 10.1038/ng.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogh J, Fogh JM, Orfeo T. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;59:221–26. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibi K, Liu Q, Beaudry GA, Madden SL, et al. Serial analysis of gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5690–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brower M, Carney DN, Oie HK, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Growth of cell lines and clinical specimens of human non-small cell lung cancer in a serum-free defined medium. Cancer Res. 1986;46:798–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gazdar AF, Linnoila RI, Kurita Y, et al. Peripheral airway cell differentiation in human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5481–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carney DN, Gazdar AF, Bepler G, et al. Establishment and identification of small cell lung cancer cell lines having classic and variant features. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2913–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Didier ES, Rogers LB, Orenstein JM, et al. Characterization of Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis isolates cultured from nasal mucosa and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from two AIDS patients. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banks-Schlegel SP, Gadzar AF, Harris CC. Intermediate filament and cross-linked envelope expression in human lung tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1187–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carney DN, Gazdar AF, Bepler G, et al. Establishment and identification of small cell lung cancer cell lines having classic and variant features. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2913–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergh J, Nilsson K, Zech L, Giovanella B. Establishment and characterization of a continuous lung squamous cell carcinoma cell line (U-1752) Anticancer Res. 1981;1:317–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaha N, Resar LMS, Vindivich D, Coffey D. High mobility protein HMGI (Y) enhances tumor cell growth, invasion, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in prostate cancer cells. The Prostate. 2004;60:160–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huhtala P, Chow LT, Tryggvason K. Structure of the Human Type IV Collagenase Gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11077–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paz-Priel I, Cai DH, Wang D, et al. CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein alpha (C/EBPalpha) and C/EBPalpha myeloid oncoproteins induce Bcl-2 via interaction of their basic regions with nuclear factor-KappaB p50. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:585–96. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minna JD, Roth JA, Gazdar AF. Focus on lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gazdar AF. The molecular and cellular basis of human lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:261–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarhadi VK, Wikman H, Salmenkivi K, et al. Increased expression of high mobility group A proteins in lung cancer. J Pathol. 2006;209:206–12. doi: 10.1002/path.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scala S, Portella G, Fedele M, Chiappetta G, Fusco A. Adenovirus-mediated suppression of HMGI (Y) protein synthesis as potential therapy of human malignant neoplasias. Proc Natl Aca, Sci USA. 2000;97:4256–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070029997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeves R, Edberg DD, Ying L. Architectural transcription factor HMGI (Y) promotes tumor progression and mesenchymal transition of human epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:575–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.575-594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passlick B, Sienel W, Seen-Hibler R, Wockel W, et al. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 predicts unfavorable outcome in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3944–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hristov AC, Cope L, Di Cell F, et al. HMGA1 correlates with advanced tumor grade and decreased survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Modern Pathology. 2009 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.139. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, et al. An embryonic stem cell-like signature in poorly differentiated aggressive tumors. Nat Genetics. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liau SS, Jazag A, Whang EE. HMGA1a is a determinant of cellular invasiveness and in vitro metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11613–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo CB, Wang S, Deng C, Zhang DL, Wang FL, Jin XQ. Relationship between matrix metalloproteinase 2 and lung cancer progression. Mol Diagn Ther. 2007;11:183–92. doi: 10.1007/BF03256240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fikret S, Qiu W, Wilentz RE, Iacbuzio-Donahue CA, Grosmark A, Su GH. RPL38, FOSL1, and UPP1 are predominantly expressed in the pancreatic ductal epithelium. Pancreas. 2005;30:158–67. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000151581.45156.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treff NR, Dement GA, Adair JE, et al. Human KIT ligand promoter is positively regulated by HMGA1 in breast and ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:8557–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zucker S, Drews M, Conner C, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) binds to the catalytic domain of the surface receptor, membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MT1-MMP) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1216–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurewitz AN, Zucker S, Mancuso P, et al. Human pleural effusions are rich in metalloproteinases. Chest. 1992;102:1808–14. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.6.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, et al. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–12. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu GS, El-Diery WS. Apoptotic death of tumor cells correlates with chemosensitivity, independent of p53 or Bcl-2. Clinical Cancer Res. 1996;2:623–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nissen MS, Langan TA, Reeves R. Phosphorylation by cdc2 kinase modulated DNA binding of high mobility group 1 nonhistone chromatin protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19945–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Southern Blot analysis was performed with ECL detection using a commercial kit (Amersham ECL Direct Nucleic Acid Labeling and Detection System) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was incubated at 37°C overnight with the restriction enzyme, EcoRI (New England Biolabs; 2 units/μg of DNA/10μl reaction volume), as we previously described13. PCR was used to generate a 312 base pair HMGA1a DNA probe using pET7C as template49. The primers were: forward-5′ CTC GAA GTC CAG CCA GCC CTT 3′, and, reverse-5′ GGT CAC TGC TCC TCC TCC GA 3′. The expected bands (arrows) show similar intensity in all 3 large cell carcinoma cell lines (H1299, H460, H661) compared to the control BEAS-2B cells and normal human DNA from lymphocytes, indicating no HMGA1 gene amplification in these cells.

Sequence analysis for HMGA1a mutations. To determine if the HMGA1 coding region was mutated in the large cell lung carcinoma cells, PCR was used to generate 171 and 208 base pair overlapping HMGA1a fragments from cDNA prepared as previously described15. The 171 base pair fragment extends from nucleotide 290 to 460 (based on reference sequence NM_145899.2) and was generated using the following primers: forward-5 ′TCA CTC TTC CAC CTG CTC CT 3′ and reverse-5 ′CTT CTG ACT CCC TAC CAG CG 3′. The 208 base pair fragment extends from nucleotide 448 to 648 and was generated using the following primers: forward-5′ CGC TGG TAG GGA GTC AGA AG 3′ and reverse-5′ GGT CAC TGC TCC TCC TCC GA 3′. Nucleotide sequencing of the PCR fragments was performed by the Johns Hopkins University Core DNA Analysis Facility by one-capillary cycle sequencing using the Applied Biosystems 3730×l DNA Analyzer (Sanger-based). There were no mutations detected in the HMGA1a coding regions in the large cell carcinoma cell lines (H1299, H460, H661).

Supplementary Fig. 2. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with sheared chromatin from different lung cancer cells after cross-linking proteins bound to DNA with formaldehyde (15). As shown in Fig. 4, the graphs indicate the relative quantity of immunoprecipitated DNA (bars) +/- the standard deviations with the following antibodies (all from Upstate, except for the HMGA1 antibody): HMGA1 (15), Polymerase II (Pol II) or histone H3, (both as positive controls), and rabbit IgG (as a negative control). Additional negative controls included no chromatin and no DNA. There is significant in vivo binding of HMGA1 to the MMP-2 promoter in the metastatic, large cell lung carcinoma cells (H661 and H460), but no significant binding in the metastatic, squamous cell carcinoma cells (U-1752 and SK-MES).

Supplementary Fig. 3. MMP-2 protein and mRNA are decreased in the H1299 cells transfected with siRNA to MMP-2 (20 nmol/L; Dharmacon) compared with cells transfected with the off-target control siRNA (siCONTROL nontargeting siRNA pool at 20 nmol/L; Dharmacon). Secreted MMP-2 and control MMP-9 protein activity were assayed by zymography at 24 h, 48 h, 8 days, and 10 days after adding the siRNA. The mRNA levels for MMP-2 and control β-actin (β-actin primer/probe set; Applied Biosystems) were assessed at the same time points. MMP-2 mRNA was normalized to β-actin as the loading control. Standard deviations for qRT-PCR were all less than 5%.

Supplementary Fig. 4. HMGA1 and MMP-2 mRNA are highly correlated in the undifferentiated, large cell carcinoma lung cancer cell lines; r = 0.96, p < 0.00001 by Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Table S1. Histologic Type and Clinical Characteristics