Abstract

This study explores the utility of using the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction as a framework for predicting cancer patients’ intentions to seek information about their cancer from sources other than a physician, and to examine the relation between patient’s baseline intentions to seek information and their actual seeking behavior at follow-up. Within one year of their diagnosis with colon, breast, or prostate cancer, 1641 patients responded to a mailed questionnaire assessing intentions to seek cancer-related information from a source other than their doctor, as well as their attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and perceived behavioral control with respect to this behavior. In addition, the survey assessed their cancer-related information seeking. One year later, 1049 of these patients responded to a follow-up survey assessing cancer-related information seeking during the previous year. Attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and perceived behavioral control were predictive of information seeking intentions, though attitudes emerged as the primary predictor. Intentions to seek information, perceived normative pressure regarding information seeking, baseline information seeking behavior, and being diagnosed with stage 4 cancer were predictive of actual information seeking behavior at follow-up. Practical implications are discussed.

Being diagnosed with cancer catapults patients and their families into an unfamiliar landscape of medical terminology, decision-making, and lifestyle changes. As a result, cancer patients encounter a new set of informational needs. Research has shown that most cancer patients (74%–98%) want as much information as possible about their disease and its treatment (Cassileth, Zupkis, Sutton-Smith & March, 1980; Chen & Siu, 2001; James, James, Davies, Harvey, & Tweddle, 1999; Jenkins, Fallowfield, & Saul, 2001). Although doctors and other medical professionals are generally the cancer patients’ primary source of information, most patients seek out additional information about the cancer itself (e.g., etiology and course of disease, physical effects of disease, and stage of disease), rehabilitation (e.g., recovery time and nutrition during recovery), and prognosis (Finney Rutten, Arora, Bakos, Aziz & Rowland, 2005; Nair, Hickok, Roscoe, & Morrow, 2000; Talosig-Garci & Davis, 2005) from a variety of interpersonal (e.g., friends, family, and other cancer patients) and mediated sources (e.g., TV, magazines, and the Internet) (Jenkins, Fallowfield, & Saul, 2001; Finney Rutten, Arora, Bakos, Aziz & Rowland, 2005; Carlsson, 2000; Mills & Davidson, 2002; Silliman, Dukes, Sullivan & Kaplan, 1998).

Some evidence suggests that information can reduce anxiety associated with the diagnosis (e.g., Davidson, Goldenberg, Gleave & Denger, 2003; Michie, Rosebert, Heaversedge, Madden & Parbhoo, 1996) and assist in coping with the effects of the disease itself (e.g., Harrison-Woermke & Graydon, 1993; Zemore & Shepel, 1987). One study found that cancer patients who sought information via the Internet participated more actively in treatment-related decision-making, and asked more questions of their doctors during a visit (Bauerle Bass, Burt Ruzek, & Gordon, 2006). However, other studies have found that information seekers and non-seekers may differ demographically (Czaja, Manfredi & Price, 2003) as well as in terms of informational coping styles (i.e. monitoring vs. blunting) (Barnoy, Bar-Tal & Zisser, 2006), suggesting that the effects of information seeking may not be independent of one’s propensity to seek out information. Nevertheless, a randomized clinical trial examining the effects of providing (or not providing) women attending an out-patient breast clinic with information prior to their initial consultation found that members of the information-receiving treatment groups experienced less anxiety about their exam, less anxiety about what the doctor might find, and perceived their problem as less serious than did those in the no-message control group (Michie et al., 1996). Studies using more macro levels of analysis have noted that rates of breast-conserving surgery were highest in states that had informed-consent laws requiring physicians to provide patients with information about different treatments options (Farrow DC, Hunt WC, Samet, 1992; Ganz, 1992; Nattinger, Gottlieb, Veum, Yahnke & Goodwin, 1992; Fraenkel & McGraw, 2007). These studies suggest that the effects of information on cancer patients’ decision-making are not limited to those who are inclined to seek out information on their own, and that encouraging cancer patients to seek out information about their cancer may lead to more informed cancer-related decision-making.

Although, some research has identified a few demographic (Czaja et al., 2003; Mayer et al., 2007) and psychological differences (Barnoy et al., 2006) between those who tend to seek out cancer-related information and those who do not, little is known about the psychosocial factors that predict cancer patient’s intentions to seek out information related to their cancer, or about the relation between intentions to seek information and actual seeking behavior. This study uses the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (IM) (Fishbein, 2000, 2008; Fishbein & Yzer, 2003) as a theoretical model for examining predictors of cancer patient’s intentions to seek information about their cancer from sources other than their doctors at baseline, as well as their actual information seeking behavior at follow-up one year later.

The Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction

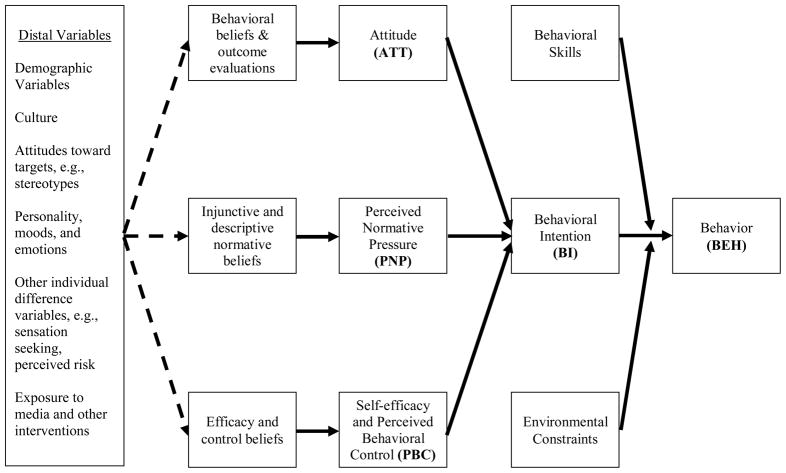

The IM is a model that specifies a set of constructs that predict behavioral performance, and is based on the health belief model (Janz & Becker, 1984; Rosenstock, 1974), the theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986), and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1988, 1991) and is illustrated in Figure 1. The IM posits that an intention to perform (or not perform) a behavior is a precondition for engaging in the behavior. Behavioral intentions (BI), in turn, are a function of attitudes (ATT) toward performing the behavior in question, perceptions of normative pressure (PNP) to engage in (or not engage in) the behavior, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) with respect to performing the behavior. More specifically, ATT toward the behavior refers to the degree to which one is in favor of or opposed to performing the behavior; is my performance of the behavior pleasant or unpleasant? Is it wise or foolish, harmful or beneficial? PNP refers to a person’s perception of the degree to which important others think he or she should or should not perform the behavior, as well as perceptions of whether or not similar or important others are themselves performing the behavior. PBC assesses a person’s belief that they do, or do not, have the ability to perform the particular behavior under a number of challenging circumstances; that performing the behavior is, or is not, under the person’s control. Also according to the IM, the influence of distal variables, such as demographic factors, cancer type, and cancer stage, on intention should be mediated through ATT, PNP, and PBC. The influence of ATT, PNP, and PBC on behavior should be mediated through BI, although in some instances PBC may have a direct influence on behavior.

Figure 1.

Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction

The Current Study

This study was designed to test some of the IMs theoretical predictions as a means for understanding the factors associated with cancer patient’s intentions to seek information and their actual information seeking behavior. Specifically, we examined three main hypotheses. First, according to the IM, behavioral intentions should be reliably predicted from the psychosocial variables ATT, PNP, and PBC. Second, the effects of demographic variables on intentions should not contribute, or contribute very little to the prediction of intentions over and above the effects of ATT, PNP, and PBC. Third, BI should have a direct and significant impact on behavior and should mediate the effects of ATT, PNP, and PBC on behavior. Tests of these relationships will provide insight into the factors that contribute to information seeking among cancer patients, and suggest strategies for modifying information seeking intentions and behavior.

Method

Patients and procedure

A list of 26,608 patients diagnosed with breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer in 2005 was obtained from the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry. This list included approximately 95% of all cancer cases that were eventually reported to the registry. After stratifying by cancer type, a sample was randomly selected of 3994 patients, of whom 2013 responded. Potential participants were contacted with a pre-notice letter explaining the purpose of the study, which included instructions for opting-out, and a brochure about the cancer registry. Three days later, surveys tailored by cancer type, along with a letter and small cash incentive were mailed to those who had not opted out. Two weeks later those who had not returned the initial survey were sent an additional letter and survey (Dillman, 2000).

In an experiment reported elsewhere (Kelly, Fraze, & Hornik, under review) 382 patients were selected to receive and filled out a shorter version of the questionnaire in which the items of interest in this study were not included. The analyses of baseline data reported here are based on responses from 1641 patients. Using response rate four from the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR, RR4) standard definitions to adjust for estimated cancer and non-cancer related deaths within Pennsylvania (AAPOR, 2006), the response rate was 60% for colorectal cancer, 68% for breast cancer, and 64% for prostate cancer participants. Baseline data were collected between September and November of 2006.

One year later, a follow-up questionnaire was sent to the 1390 respondents who received the baseline survey containing measures of the IM variables and who indicated we could contact them again. We received 1049 responses to the follow-up survey. Again, using AAPOR RR4 (AAPOR, 2006), the follow-up response rates to follow-up questionnaires were 82% for colon cancer and 83% for both breast and prostate cancer. Table 1 more fully describes the characteristics of the baseline and follow-up samples. Prior to the study survey items were pilot tested using interviews with cancer patients.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Baseline (N = 1641) n (%) or mean (sd) | Follow-up (N = 1049) n (%) or mean (sd) | Sig. Test (Attrition)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 23–103 | 24–103 | |

| Mean (sd) age at Diagnosis | 64.66 (12.36) | 64.05 (11.95) | t = 2.68, p = .007 |

| Male | 809 (49.3%) | 514 (49.0%) | χ2 (1) = 0.11, p = .746 |

| Female | 832 (50.7%) | 535 (51.0%) | |

| Cancer Type | |||

| Breast | 539 (32.8%) | 352 (33.6%) | χ2 (2) = 3.45, p = .178 |

| Colon | 587 (35.8%) | 358 (34.1%) | |

| Prostate | 515 (31.4%) | 339 (32.3%) | |

| Highest Level of Education | |||

| Less than high school | 260 (16.0%) | 136 (13.0%) | χ2 (3) = 33.82, p < .001 |

| High school or GED | 659 (40.7%) | 413 (39.4%) | |

| Some college (1–3) years | 360 (22.2%) | 244 (23.3%) | |

| College graduate | 342 (21.1%) | 254 (24.3%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1329 (81.0%) | 886 (84.5%) | χ2 (2) = 22.90, p < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 232 (14.1%) | 120 (11.4%) | |

| Other | 80 (4.9%) | 43 (4.1%) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 1108 (68.7%) | 745 (71.6%) | χ2 (2) = 11.98, p = .003 |

| Divorced or separated | 397 (24.6%) | 230 (22.1%) | |

| Never married | 108 (6.7%) | 65 (6.3%) | |

| Cancer Stage | |||

| Stage 0 | 146 (9.5%) | 88 (8.9%) | χ2 (4) = 21.34, p < .001 |

| Stage 1 | 286 (18.6%) | 193 (19.5%) | |

| Stage 2 | 621 (40.4%) | 425 (43.0%) | |

| Stage 3 | 200 (13.0%) | 130 (13.2%) | |

| Stage 4 | 284 (18.5%) | 152 (15.4%) | |

Note.

All chi-square tests compare participants who responded at follow-up to those who did not. Cancer stage was determined from clinical data available from the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry.

Measures

Baseline

The current study is based on responses to questions assessing respondent’s intentions to actively seek information related to their cancer from sources other than their doctors in the next 12 months, attitudes about seeking such information, as well as perceived norms and perceived control with respect to this behavior. We also examine past information seeking behavior.

Behavioral intentions (BI) were measured using a single item reading “How likely is that you will actively seek information about issues related to your cancer from a source other than your doctor in the next 12 months” scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale anchored by “very unlikely” and “very likely.” Attitudes toward information seeking were assessed by averaging responses to three semantic differential scales; “My actively seeking information about issues related to my cancer from a source other than my doctor in the next 12 months would be…” useless – useful; unenjoyable – enjoyable; foolish – wise. Perceived behavioral control (PBC) was measured by averaging responses to two items; “My actively seeking information about issues related to my cancer from a source other than my doctor in the next 12 months would be…” not up to me – up to me, and “If I really wanted to, I could actively seek information about issues related to my cancer from a source other than my doctor in the next 12 months” disagree – agree. Perceived normative pressure (PNP) was measured by averaging responses to two items; Most people like me (e.g. other cancer patients) actively seek information about issues related to their cancer from a source other than their doctors” and “Most people who are important to me think I should actively seek information about issues related to my cancer from a source other than my doctor in the next 12 months.” Both items were anchored by disagree agree. All semantic differential items were scored −3 to +3.

We measured past information seeking by asking respondents to indicate from which of 12 sources they had sought information about issues related to their cancer in the time since their diagnosis. The sources included interpersonal sources (e.g., doctors, family and friends, other cancer patients) and mediated sources (e.g., TV and radio, newspapers and magazines, the Internet) as well as an “other” option to capture sources not listed. Respondents were categorized as seekers if they sought from at least one source other than doctors and other medical professionals and as non-seekers if they had not sought from any source or only from a doctor or other medical professional. Details on the types of information cancer patients sought out and sources of that information are described more fully in Nagler et al (under review).

Follow-up

In order to maintain correspondence between the measures of ATT, PNP, PBC, BI, and the follow-up behavior measure participants indicated which of 12 sources they sought information from in the past 12 months. The response options and computation of seeking and non-seeking at follow-up were identical to the baseline measure.

Analyses

We used a one-sample t-test to test whether the mean level of intentions to seek information was significantly different from the scale’s midpoint. ANOVAs (with post-hoc comparisons where appropriate) were used to examine differences in mean levels of information seeking intentions by cancer type. A chi-square analysis was used to examine the proportions of intenders and non-intenders by cancer stage. We used MANOVAs to test differences between intenders and non-intenders on ATT, PNP and PBC. Linear regression was used to predict seeking intentions at baseline. Stepwise logistic regression models with forced entry were used to predict seeking behavior at follow-up.

Results

Baseline

Seeking behavior

Overall, at baseline, 80% of respondents indicated they had sought information about their cancer from at least one source other than their doctor in the time (one year or less) between their diagnosis and the completion of the survey.

Mean group differences

Across all cancers the mean for intentions to seek cancer-related information in the next 12 months was negative (M = −0.92, SD = 2.16), and significantly below the scale midpoint of zero, t(1525) = −16.63, p < .001. Mean levels of intentions differed by cancer, F(2, 1520) = 10.63, p < .001, and breast cancer patients reported stronger intentions to seek cancer-related information in the future (M = −0.56, SD = 2.19) than did those with prostate (M = −1.15, SD = 2.08) or colon (M = −1.05, SD = 2.16) cancer, ps < .001. Intentions did not differ between those with colon and prostate cancer. Analyses also indicated that although women had stronger intentions to seek information in the future (M = −0.71, SD = 2.18) than did men (M = −1.13, SD = 2.12), t(1521) = 14.31, p < .001, d = 0.19, this largely reflected the higher seeking intentions for breast cancer. Intentions did not differ between men and women with colon cancer. Intentions to seek information differed also by cancer stage, F(2, 1421) = 7.06, p = .001. Post-hoc analyses indicated that those with less advanced disease (stages 0, 1, and 2) had lower intentions to seek (M = −1.06, SD = 2.11) than did those with stage 3 (M = −0.53, SD = 2.22), F(2, 1421) = 4.88, p =.008 or stage 4 (M = −0.67, SD = 2.27), F(2, 1421) = 3.48, p =.031 disease. The difference between stage 3 and stage 4 was not significant, F(2, 1421) = 0.23, p =.794.

As Table 2 illustrates, patients who said it was likely that they would seek in the next 12 months (those who scored 1, 2, or 3 on the intention measure) held more positive attitudes toward seeking, perceived more social pressure to seek information, and expressed having more control over seeking compared to those who indicated they were not likely to seek (those who scored −3, −2, −1 or 0 on the intention measure). It should be noted that both those who indicated they were likely to seek and those who indicated they were unlikely to seek reported relatively high levels of control over information seeking.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Mean differences between Intenders and Non-Intenders

| Likely to Seek | Unlikely to Seek | t | p< | Effect Size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| ATT (α = 0.89) | 1.39 | 1.34 | −0.82 | 1.83 | 25.01 | .001 | 1.30 |

| Useful | 1.84 | 1.41 | −0.63 | 2.04 | 25.54 | .001 | 1.32 |

| Enjoyable | 0.64 | 1.68 | −1.21 | 1.71 | 17.73 | .001 | 1.09 |

| Wise | 1.58 | 1.79 | −0.53 | 2.15 | 18.21 | .001 | 1.03 |

| PNP (r = 0.53) | 0.70 | 1.79 | −1.17 | 1.70 | 18.84 | .001 | 1.08 |

| Injunctive norm | 0.38 | 2.25 | −1.60 | 1.93 | 15.74 | .001 | 0.98 |

| Descriptive norm | 1.02 | 1.83 | −0.71 | 2.03 | 15.59 | .001 | 0.87 |

| PBC (r = 0.37) | 2.02 | 1.34 | 0.82 | 2.00 | 13.39 | .001 | 0.65 |

| Up to me | 2.07 | 1.52 | 0.67 | 2.40 | 12.71 | .001 | 0.65 |

| Could seek | 2.00 | 1.63 | 0.98 | 2.27 | 9.51 | .001 | 0.48 |

Note. Positive effect sizes (Cohen’s d) indicate higher scores for intenders. Due to missing data, Ns for intenders range from 378 to 434, and ns for non-intenders range from 899 to 1092. α the measure internal consistency, r is the inter-item correlation. Both rs are significant, ps <.001.

Predicting seeking intentions

In Step 1 of the regression model intentions were predicted from IM predictors (ATT, PNP, and PBC). Background variables (i.e. demographics, cancer stage, and cancer type) were added in Step 2. Coefficients and significance tests for Step 2 of this model appear in Table 3. As Table 3 illustrates, ATT (β = .442, p < .001), PNP (β = .251, p < .001), and PBC (β = −.059, p = .024) were all significantly associated with intentions to seek information, though ATT was the factor most strongly associated with intentions. Together, ATT, PNP, and PBC accounted for 40% of the variance in intentions. Some of the background variables added in Step 2 were significantly associated with seeking intentions. Specifically, there were negative associations between seeking intentions and highest level of educational attainment (high school education β = −.088, p = .002; less than high school, β = −.066, p = .013) and age at diagnosis (β = −.110, p < .001). Having breast cancer (β = .055, p = .034) and being diagnosed with advanced stage disease (Stage 3, β = .086, p < .001; Stage 4, β = .047, p = .033) were positively associated with seeking intentions. Entering the background variables in Step 2 increased the adjusted R2 by 3%, F(3, 1251) = 226.74, p < .001. These results provide support for the hypotheses that ATT, PNP, and PBC should predict intentions and that background variables should contribute relatively little to the prediction of intentions. Models that included the interaction of cancer type and stage yielded identical results and the interaction terms were not significant.

Table 3.

Predicting Seeking Intentions at Baseline

| Model Step & Variables Entered | β | t | p≤ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| ATT | .442 | 15.94 | .001 |

| PNP | .251 | 9.86 | .001 |

| PBC | −.059 | −2.25 | .024 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Comparison: College Grad. | |||

| Some College | −.026 | −0.97 | .333 |

| High School | −.088 | −3.15 | .002 |

| Less than HS | −.066 | −2.47 | .013 |

| Comparison: Whites | |||

| Black | .038 | 1.67 | .092 |

| Other | .016 | 0.73 | .465 |

| Age | −.110 | −4.62 | .001 |

| Comparison: Married | |||

| Divorced or separated | .042 | 1.82 | .069 |

| Never married | .027 | 1.24 | .214 |

| Comparison: Colon | |||

| Breast | .055 | 2.12 | .034 |

| Prostate | .007 | 0.26 | .796 |

| Comparison: Stages 0–2 | |||

| Stage 3 | .086 | 3.76 | .001 |

| Stage 4 | .047 | 2.14 | .033 |

| Adjusted Model R2 = .43 | |||

Note. All regression coefficients are from Step 2 after controlling for demographic covariates in Step 1. Step 1 adjusted R2 = 0.40 Gender was not included as a covariate because it was collinear with cancer type. N = 1267.

Follow-up

Predicting seeking behavior

Overall, 54% sought information from at least one source other than their doctor in the previous 12 months (compared to 80% at baseline). Seventy-six percent of those who at baseline indicated they were likely to seek information reported at follow-up having sought information in the previous 12 months. However, 41% of those who said it was unlikely that they would seek information, did seek information at follow-up.

According to the IM, behavioral intentions mediate the influence of ATT, PNP, and PBC on behavior, and background variables should not contribute to the prediction of behavior over and above intentions. In step 1 of a 4-Step logistic regression model ATT, PNP, PBC was regressed on behavior. In this model ATT (OR = 1.28, p < .001) and PNP (OR = 1.19, p = .001) were predictive of behavior but PBC was not (OR = 0.98, p = .730). As seen in Table 4, when intentions were added in Step 2, it was a significant predictor of behavior (OR = 1.30, p < .001). ATT (OR = 1.11, p = .066) and PBC (OR = 1.00, p = .959) were not predictive of behavior and there was a marginally significant association between PNP and behavior (OR = 1.11, p = .053). Because past behavior is usually a strong predictor of future behavior it was added in Step 3 and was highly significant, (OR = 2.79, p < .001). Yet, intentions remained a significant predictor of behavior. Also, when past behavior was added to the model the relationship between PNP and behavior became statistically significant. Finally, when the background variables were added in Step 4 all of the patterns in Step 3 remained; PNP, intentions, and past information seeking were predictive of behavior. Having stage 4 cancer was the only background variable that was significantly associated with behavior (OR = 2.47, p < .001).

Table 4.

Regression Models Predicting Information Seeking Behavior at Follow-up

| Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p≤ | OR | 95% CI | p≤ | OR | 95% CI | p≤ |

| ATT | 1.11 | 0.99 – 1.24 | .066 | 1.10 | 0.98 – 1.23 | .101 | 1.11 | 0.99 – 1.25 | .075 |

| PNP | 1.11 | 1.00 – 1.23 | .053 | 1.12 | 1.01 – 1.24 | .040 | 1.13 | 1.01 – 1.26 | .028 |

| PBC | 1.00 | 0.91 – 1.10 | .959 | 0.99 | 0.90 – 1.09 | .845 | 0.98 | 0.88 – 1.08 | .642 |

| BI | 1.30 | 1.18 – 1.43 | .001 | 1.26 | 1.14 – 1.39 | .001 | 1.22 | 1.11 – 1.35 | .001 |

| Baseline Seeking | --- | --- | --- | 2.79 | 1.80 – 4.31 | .001 | 2.85 | 1.79 – 4.53 | .001 |

| Comparison: College Grad. | |||||||||

| Some College | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.02 | 0.64 – 1.62 | .935 |

| High School | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.94 | 0.61 – 1.43 | .761 |

| Less than HS | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.74 | 0.40 – 1.34 | .314 |

| Comparison: Whites | |||||||||

| Black | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.57 | 0.90 – 2.73 | .112 |

| Other | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.81 | 0.71 – 4.60 | .214 |

| Age | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.00 | 0.99 – 1.02 | .939 |

| Comparison: Married | |||||||||

| Divorced or separated | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.75 | 0.49 – 1.14 | .179 |

| Never married | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.56 | 0.76 – 3.21 | .224 |

| Comparison: Colon | |||||||||

| Breast | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.36 | 0.90 – 2.07 | .149 |

| Prostate | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.89 | 0.58 – 1.34 | .566 |

| Comparison: Stages 0–2 | |||||||||

| Stage 3 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.46 | 0.88 – 2.41 | .142 |

| Stage 4 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 2.47 | 1.51 – 4.03 | .001 |

| a Model Fit | χ2 (8) = 3.83, p = .872 | χ2 (8) = 5.40, p = .714 | χ2 (8) = 6.98, p = .538 | ||||||

| b Pseudo R2 | .175 | .208 | .247 | ||||||

Note:

Hosmer and Lemeshow test.

Naglekerke R2. The BI measure is continuous. N = 792

Discussion

Although numerous studies have examined the sources that cancer patients consult for information about their cancer, and the types of information they look for (e.g., Finney Rutten et al., 2003), this is the first study to examine the attitudinal, normative, and control factors that drive cancer patient’s intentions to seek information about their cancer from sources other than their doctors, as well as their actual information-seeking behavior. This study demonstrates that the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein, 2000, 2008; Fishbein & Yzer, 2003) is a useful model for understanding the psychosocial predictors of cancer patient information-seeking intentions and behavior. Specifically, patients’ intentions to seek information about their cancer from sources other than their doctor(s) were reliably associated with ATT, PNP, and PBC about information seeking. Seeking intentions were driven primarily by attitudes toward seeking and normative pressure and PBC played a relatively minor role in accounting for seeking intentions. These findings are consistent with others who have found that attitudes and normative pressure are predictive of cancer patients’ intentions to seek out psychosocial support in the form of support groups, social workers, and others (Steginga, et al., 2008).

Also noteworthy is the fact that, although their contribution to the prediction of intentions was small (together they accounted for an additional 3%), level of education, age, having breast cancer, and being diagnosed with advanced stage disease contributed significantly to the prediction of seeking intentions over and above the IM constructs. The theoretical explanation is that these background variables are proposed to influence the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs that underlie ATT, PNP, and PBC respectively, not necessarily through the direct measures of these constructs included in this study. Nevertheless, in practice it is important to realize that older individuals and those with lower levels of education are less likely, and those with breast cancer and more advanced stages of cancer are more likely to intend to seek out information from sources other than their doctors.

The majority (76%) of those who expressed intentions to seek at baseline reported having sought at follow-up. As predicted by the IM, intentions to seek predicted actual seeking and mediated the effects of ATT and PNP on behavior (there was no direct effect of PBC on behavior). Being diagnosed with stage 4 cancer was the only background variable associated with seeking behavior after accounting for the predicted effects of the IM constructs and past seeking behavior. Interestingly, there was a significant effect of PNP at baseline on follow-up behavior that was not entirely mediated by intentions. One possible explanation is that those who experienced more normative pressure to seek out information at baseline eventually complied and sought information at follow-up even though at baseline they had not initially intended to do so. The effect of PNP on behavior may also help to account for a portion of the 41% of respondents who did not express intentions to seek at baseline but reported seeking at follow-up. This finding also suggests that many cancer patients may not anticipate the advent of new health or psychosocial issues about which they might seek information, and seems to indicate that a considerable proportion of cancer-related information seeking occurs in response to unanticipated informational needs. Our results might be accounted for if patients’ attitudes towards seeking became more positive and/or they experienced substantial normative pressure to seek between baseline and follow-up.

Finally, compared to those diagnosed with less advanced disease (stages 0, 1, and 2), being diagnosed with advanced stage disease was predictive of both intentions to seek and actual seeking of cancer-related information from sources other than one’s doctor(s). Others have found that relative to medical treatment information, patients receive significantly less advice about psychosocial care and must therefore seek out that information on their own, and those who experience more cancer-related distress have stronger intentions to seek (Steginga, et al., 2008). Although our data do not speak to this directly, it is likely that compared to those diagnosed with less advanced disease, those diagnosed with more advanced disease may experience more distress and be faced more acutely with psychosocial issues about which information from sources other than their doctors may be quite useful (e.g., learning to live with cancer, and end of life issues).

Practical implications

Information seeking among cancer patients is a fairly common behavior, and previous research suggests that information seeking is associated with a number of positive outcomes (Butow, Boyer, & Tattersall, & Brown, 1999; Davidson, et al., 2003; Ganz, 1992; Michie, et al., 1996). Given that intentions to seek information were most strongly associated with attitudes toward information seeking, persuasive appeals targeting patient’s attitudes toward information seeking by highlighting the usefulness of information seeking will likely lead to changes in information seeking intentions and behavior. The finding that norms are also important predictors of information seeking intentions and given that doctors and family members are among cancer patients’ most important referents (e.g., Talosig-Garcia & Davis, 2005) it would seem that these referents can have a significant impact on the patients’ information seeking behaviors. In addition, it could be hypothesized that older individuals and those with lower levels of education are most likely to benefit from encouragement to seek out information. However, research has shown that some informational resources are of questionable quality (Chen & Siu, 2001; Hoffman-Goetz & Clarke, 2000; Silberg, Lundberg, & Musacchio, 1997). Providing patients with a circumscribed list of reliable informational resources may make the information seeking process more enjoyable and assure exposure to high-quality information. Future research could test these hypothesized causal associations by examining the effects of persuasive messages aimed at creating positive attitudes towards seeking information about cancer. More specifically, according to the Integrative Model, one strategy would be to identify the specific behavioral beliefs that distinguish those who intend to seek information from those who do not. Messages should emphasize positive beliefs about information seeking held by intenders and redress negative beliefs held by non-intenders. Also, according to the results reported here and the IM’s theoretical predictions, these messages might be most effective if delivered by an important source of social influence such as the patient’s doctor or significant other.

Limitations

We should note some specific limitations of this study. This study’s sample consisted entirely of Pennsylvania residents who may not be representative of cancer patients from other regions. Generalization of these results to other populations should be made cautiously where reason exists to believe that cancer patients in Pennsylvania differ from other populations on relevant dimensions. Also, this study relied exclusively on self-report data and no attempt was made to verify any actual information seeking. As such, rates of reported seeking behavior are subject to the problems inherent in using self-report data such as recall bias and social desirability influences. Another limitation is that the study did not measure patient’s anxiety about their cancer or their level of literacy, two factors that research suggests may be associated with cancer information seeking (Dubois & Loiselle, 2009; Kim, et al., 2003). In addition, some research suggests that there are gender differences with regard to the use of and satisfaction with cancer information (e.g., Dubois & Loiselle, 2009). Because we chose to examine patterns across three types of cancer and cancer type was confounded with gender, our findings are not informative with regard to any gender differences in cancer information seeking intentions or behavior.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Hennessy and Stacy Gray for their helpful comments on previous drafts of this manuscript. We are also grateful to the Seeking and Scanning research group at the Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication Research for developing and conducting the research analyzed here. Preparation of this manuscript was made possible by grant number 5P50CA095856-03 from the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago, IL: Dorsey; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 4. Lenexa, KS: American Associationfor Public Opinion Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barnoy S, Bar-Tal Y, Zisser B. Correspondence in informational coping styles: How important is it for cancer patients and their spouses? Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41:105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bauerle Bass S, Burt Ruzek S, Gordon TF. Relationship of the internet health information use with patient behavior and self-efficacy: Experiences of newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11:219–236. doi: 10.1080/10810730500526794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Butow PN, Boyer MJ, Tattersall MHN. Promoting patient participation in the cancer consultation: Evaluation of a prompt sheet and coaching in question asking. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;80:242–248. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M. Cancer patients seeking information from sources outside the health care system. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:453–457. doi: 10.1007/s005200000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V. Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1980;92:832–836. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-6-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Siu LL. Impact of the media and the internet on oncology: Survey of cancer patients and oncologists in Canada. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:4291–4297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja R, Manfredi C, Price J. The determinants and consequences of information seeking among cancer patients. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:529–562. doi: 10.1080/716100418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison BJ, Goldenberg L, Gleave ME, Denger LF. Provision of individualized information to men and their partners to facilitate treatment decision making in prostate cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30:107–114. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois S, Loiselle CG. Cancer informational support and health care service use among individuals newly diagnosed: a mixed methods approach. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009;15:346–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow DC, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Geographic variation in the treatment of localized breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:1097–1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel L, McGraw S. Participation in medical decision making: The patients’ perspective. Medical Decision Making. 2007;27:533–538. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07306784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2000;12:273–278. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. A Reasoned action approach to health promotion. Medical Decision Making. 2008;28:834–844. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08326092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health interventions. Communication Theory. 2003;13:164–183. [Google Scholar]

- Finney Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: A systematic review of research (1980–2003) Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;57:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA. Treatment options for breast cancer – Beyond survival. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:1147–1148. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Woermke DE, Graydon JE. Perceived informational needs of breast cancer patients receiving radiation therapy after excisional biopsy and axillary node dissection. Cancer Nursing. 1993;16:449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman-Goetz L, Clarke JN. Quality of breast cancer sites on the World Wide Web. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2000;91:281–284. doi: 10.1007/BF03404290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C, James N, Davies D, Harvey P, Tweddle S. Preferences for different sources of information about cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;37:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz N, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: Results from a large study in UK cancer centers. British Journal of Cancer. 2001;84:48–51. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BJ, Fraze TK, Hornik RC. Response rates to a mailed survey of representative cancer patients: incentive and length effects. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SP, Knight SJ, Tomori C, Colella KM, Schoor RA, Shih L, et al. Health literacy and shared decision making for prostate cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Cancer Investigation. 2001;19:684–691. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100106143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer DK, Tewrrin NC, Kreps GL, Menon U, McCance K, Parsons SK, Mooney KH. Cancer survivors information seeking behaviors: A comparison of survivors who seek and do not seek information about their cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;65:342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Rosebert C, Heaversedge J, Madden S, Parbhoo S. The effects of different kinds of information on women attending an out-patient breast clinic. Psychology Health and Medicine. 1996;1:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Mills ME, Davidson R. Cancer patients’ sources of information: Use and quality issues. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:371–378. doi: 10.1002/pon.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagler RH, Gray SW, Romantan A, Kelly BJ, DeMichele A, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Hornik RC. Early stage colorectal cancer patients less prone to seek cancer information than breast and prostate cancer patients: Results from a population-based survey. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair MG, Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR. Sources of information used by patients to learn about chemotherapy side effects. Journal of Cancer Education. 2000;15:19–22. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattinger AB, Gottlieb MS, Veum J, Yahnke D, Goodwin JS. Geographic variation in the use of breast-conserving treatment for breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:1102–1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monogrraphs. 1974;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant lector et viewor—Let the reader and viewer beware. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1244–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, Kaplan SH. Breast cancer care in older women: sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer. 1998;83:706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steginga SK, Campbell A, Ferguson M, Beeden A, Walls M, Cairns W, Dunn J. Socio-demographic, psychosocial and attitudinal predictors of help seeking after cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:997–1005. doi: 10.1002/pon.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talosig-Garcia M, Davis SW. Information-seeking behavior of minority breast cancer patients: An exploratory study. Journal of Health Communications. 2005;10:53–64. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore R, Shepel LF. Information seeking and adjustment to cancer. Psychological Reports. 1987;60:874. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1987.60.3.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]