Abstract

Trichloroethylene is an organic solvent used as an industrial degreasing agent. Due to its widespread use and volatile nature, TCE is a common environmental contaminant. Trichloroethylene exposure has been implicated in the etiology of heart defects in human populations and animal models. Recent data suggest misregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in H9c2 cardiomyocyte cell line after TCE exposure. We hypothesized that misregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis alters myocyte function and leads to changes in embryonic blood flow. In turn, changes in cardiac flow are known to cause cardiac malformations. To investigate this hypothesis, we dosed developing chick embryos in ovo with environmentally relevant doses of TCE (8 ppb and 800 ppb). RNA was isolated from control and treated embryos at specific times in development for real-time PCR analysis of blood flow markers. Effects were observed on Endothelin-1 (ET-1), Nitric Oxide Synthase-3 (NOS-3) and Krüppel-Like Factor 2 (KLF2) expression relative to TCE exposure and consistent with reduced flow. Further, we measured function in the developing heart after TCE exposure by isolating cardiomyocytes and measuring half-width of contraction and sarcomere lengths. These functional data showed a significant increase in half-width of contraction after TCE exposure. These data suggest that perturbation of cardiac function contributes to the etiology of congenital heart defects in TCE-exposed embryos.

Introduction

Trichloroethylene (TCE; TRI; C2HCl3) is an organic solvent used as an industrial degreasing agent that can be found in many consumer products (Page et al. 2001). Due to its widespread use and volatile nature, TCE is a common environmental contaminant. TCE was first linked to altered heart development in an epidemiological study that found an odds ratio of 3 for congenital heart disease in children living in an area of the Tucson Valley with TCE groundwater contamination in the range of 100–270 ppb. The types of defects found included defects expected from both myocardial and valvular etiologies. A subsequent epidemiological study found a correlation between the proximity of maternal residence to TCE emitting sites and increased heart defects in children (Yauck et al. 2004).

A connection between congenital heart disease and TCE has been a controversial issue for many years (see Boyer et al. 2000; Dugard, 2000). A recent review by Hardin et al. (2005) challenged the idea that TCE is a teratogen based largely upon inconsistencies in dose response data to various exposure protocols. At higher doses, differences in exposure method (maternal exposure via gavage in an oil carrier or dissolved in drinking water) produced different outcomes (normal vs. teratogenic, respectively) in rat embryos (Fisher et al. 2001; Johnson et al. 2003). Previously, we showed that gene expression of a number of molecules, including Serca2, was altered by 100 ppm TCE exposure in maternal drinking water of Sprague-Dawley rats (Collier et al. 2003). A subsequent study using the rat H9c2 cardiomyocyte cell line found altered expression of Serca2 and other calcium homeostatic genes with concomitant changes in a calcium flux stimulated by vasopressin (Caldwell et al. 2008). More profound changes were seen at 10 ppb than at 1ppm in this cell line. Drake et al. (2006) found that low levels (8 ppb) of TCE exposure in chick embryos produced changes in aortic flow that were greater than observed at higher levels (800 ppb). An evaluation by the National Research Council concluded that a connection between TCE and heart defects was plausible but need more study on low dose effects and mode of action (Research Council (U.S.) 2006).

Due to calcium’s importance in muscle contraction, the consequences of TCE exposure on the functional and morphological formation of the myocardium may be relevant to understanding TCE mediated cardio-teratogenicity. Drake et al. (2006) suggested that the reduced aortic flow was most likely due to obstruction caused by hypertrophy of the valve-forming cardiac cushions. We speculate that a reduction in calcium homeostasis in myocytes would impair myocyte function and have direct morphogenetic consequences. Hogers el al. (1997) showed that reduced cardiac blood flow, alone, lead to morphological heart defects. Accordingly, we exposed developing chick embryos to low level TCE during a critical stage in cardiac development. We show here, by both molecular markers of cardiac blood flow and measurement of contraction in TCE-exposed primary cardiomyocytes, that low level TCE exposure perturbs cardiac function in the living embryo. These data argue that one mechanism of TCE-mediated cardiac teratology is by a reduction of cardiac function during development.

Material and Methods

Trichloroethylene ACS reagent, ≥ 99.5% (TCE) was ordered from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO) Catalog #251402.

Dosing

TCE was dosed at 8 ppb (60 nM) and 800 ppb (6000 nM) through injection into stage Hamburger Hamilton (HH)13 eggs as reported by Drake et al. (2006). Injections were performed using Hamilton Co. (Reno, NV) 800 Series Syringes (Part #7646-01) paired with custom needles (Part #7806-02: RN NDL 6/PK (22s/1”/4)L).

Quantitative real-time PCR

After dosing, embryos were allowed to develop for 24hrs or 48hrs until reaching stages HH17 and HH24, respectively for analysis. Pooled samples of 18–21 Hamburger Hamilton (HH) 17 whole hearts were then homogenized in Trizol (# 15596-018, Invitrogen) and processed for RNA isolation using PureLink™ Micro-to-Midi™ Total RNA Purification System (# 12183-018, Invitrogen). This protocol was then repeated for pooled samples of stage (HH) 24 whole hearts. Data shown is a representation of three experimental replicates representing a total of 60 whole hearts per treatment for each exposure period (24hrs and 48hrs). cDNA was then transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). cDNA concentration was measured using fluorometry (Turner Biosystems) after staining with Quant-iT™ OliGreen® ssDNA Assay Kit (# O11492, Molecular Probes) and equal aliquots of control and experimental cDNA samples were added to triplicate reaction mixtures. Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using primers in Table 1, FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche) and the Rotor Gene 3000 System from Corbett Research. Analysis of the data was carried out using the Rotor Gene 6 software. All real-time PCR results were then normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. GAPDH expression was essentially unaltered in TCE-treated and control samples after normalizing total cDNA in each tube, showing that GAPDH expression is unaltered by TCE exposure.

Table 1.

Real-Time PCR Primers

| Primers | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelin-1 | 5’-TGTTCCCTATGGTCTTGGAGGC-3’ | 5’-AGGTTTTCTCTGCTGTGGACTGAG-3’ |

| Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 | 5’-ATGTCCTCCCCCTACACCAAC-3’ | 5’-TGCCTCCTCTTCCTCTTCCAG-3’ |

| Krüppel Like Factor 2 | 5’-CCCACGCAAAGAGGATGAAGAC-3’ | 5’-GCTTGATGCTGTCCACGAACTG-3’ |

| GAPDH | 5’-GTGTGCCAACCCCCAATGTCT-3’ | 5’-CCCATCAGCAGCCTTCA-3’ |

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

Embryos were collected in Tyrode’s solution and the thorax region dissected from the embryo. Thoraxes were fixed in a solution of 20°C 80% methanol/20% DMSO and cryosubstituted in 100% ethanol at 20°C for one week. The tissues were then embedded in paraffin and sectioned. After deparaffinization, the sections were rinsed in 1XPBS for 10 min, blocked for 1 hr at room temperature with a blocking solution containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. Sections containing the heart were processed using indirect immunofluorescence. Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibody (rabbit anti-LKLF H-60, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-28675) at 4°C in a moist chamber. After several rinses in 1XPBS, Alexa fluor 488 or 546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary anti-body (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; A-11008, A-11010) were incubated for 1 hr at room temperature in a moist chamber. After rinsing in PBS, the nuclei were stained with TOPO3 (Molecular Probes) and the sections mounted using Prolong Gold mounting media (Molecular Probes). Sections were analyzed using a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope or with a Deltavision deconvolution microscope.

Cardiomyocyte Isolation

Cells were isolated as described previously (Li et al. 1997; O'Connell et al. 2007) but as the protocol required larger hearts, embryos were incubated to day E18 after a one time yolk injection at stage 13 (E2). Briefly, following cervical dislocation of E18 chick embryos, hearts were dissected and cannulated via the aorta. Isolated hearts were perfused for four minutes at 41°C and pH 7.4 with perfusion buffer (113 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 12 NaHCO3, 10 KHCO3, 10 HEPES, and 30 Taurine, all in mM). Heart perfusion was switched to digestion buffer (perfusion buffer plus 0.148 mg/ml liberase blendzyme 2 (or 2 mg/ml Collagenase II from Worthington Biochemical and no trypsin), 0.13 mg/ml of trypsin, 12.5 µM CaCl2) for 1.5–3 min. When the heart was flaccid, digestion was halted and the heart placed in myocyte stopping buffer 1 (perfusion buffer plus 0.04 ml Bovine Calf Serum (BCS)/ml buffer and 5 µM CaCl2). The heart was cut into small pieces. Small pieces of left ventricle were then triturated several times with a transfer pipet and then filtered through a 300 µm nylon mesh filter. Following this, the cells were gravity pelleted and the supernatant was discarded. Finally, Ca2+ was reintroduced stepwise to a final concentration of 1.0 mM.

Cardiomyocyte Contractility

An inverted Olympus IX-70 microscope was used with a modified chamber to mount the mechanical interrogation apparatus. The chamber has platinum electrodes to electrically stimulate cells and a perfusion line with heater control (Cell μControls HPRE-2) and suction out to maintain a flow rate of ~1 ml/min. Sarcomere length (SL) was measured with an Ion Optix MyocamS (250 Hz sampling frequency) attached to a computer. Data was collected through an Ion Optix FSI A/D board and IonWizard software with SarcLen and SoftEdge modules to determine SL. Individual cardiomyocytes were measured at a stimulus frequency of 0.5 Hz for a minimum of five minutes. ~30 seconds of individual contractions were averaged from each cell after five minutes in the chamber to obtasin and average contraction. Diastolic SL, systolic SL, peak change SL, half-height half-width (time greater than 50% of diastolic SL) and shortening and relengthening velocity were measured for each cell. The contactility measurements were obtained from two independent replicates and a total of 18–20 TCE exposed or control cells.

Results

Altered Gene Expression after TCE Exposure

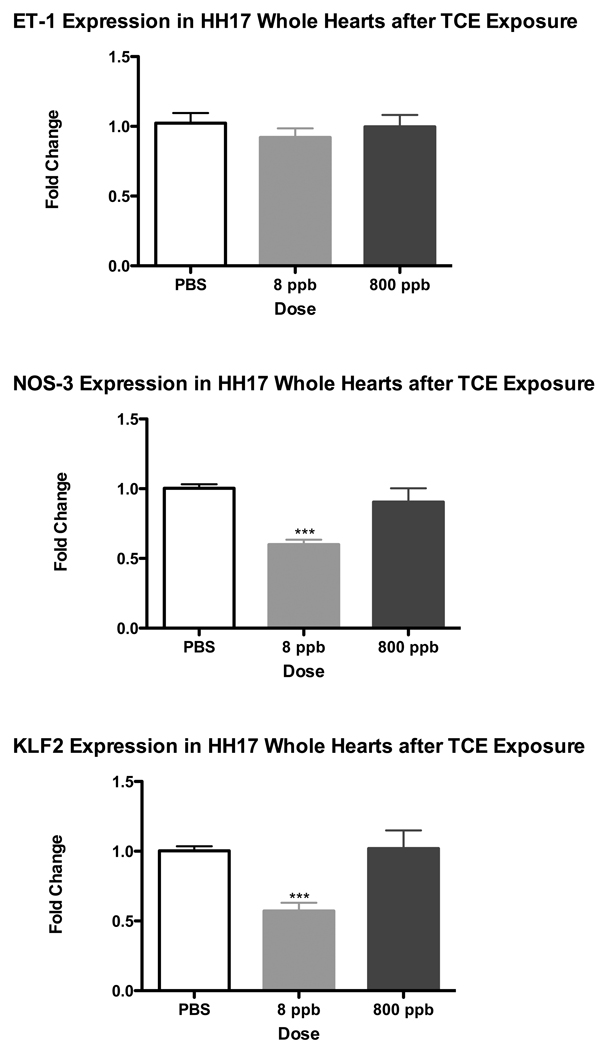

Shear stress markers, specifically Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 (NOS-3) and Krüppel Like Factor 2 (KLF2) provide a characteristic reduction in expression where blood flow is reduced in the embryo while Endothelin-1(ET-1) is a more variable marker (Groenendijk et al. 2004). Reduction in aortic blood flow was seen by Drake et al. (2006), after TCE exposure but attributed to obstructed flow from the heart by outflow cushion hypertrophy. As calcium homeostasis is perturbed by TCE in cardiomyocytes, we explored whether changes in shear stress markers in the heart might reflect a reduction of cardiac function. ET-1, NOS-3 and KLF2 were examined by real-time PCR to determine changes in transcript expression after TCE exposure. Incubated avian embryos were exposed to TCE by injection into the yolk at 48 hrs of development (HH Stage 13), these embryos were allowed to develop for another 24 hrs (to reach HH 17) at which time whole heart tissue was extracted for RNA isolation. Real time PCR was performed on the isolated RNA and normalized to GAPDH expression. We verified that GAPDH expression was not sensitive to TCE exposure by evaluating GAPDH levels in total cDNA from treated and untreated samples. Results in Figure 1 illustrate that NOS-3 and KLF2 display a significant decrease in expression after 8 ppb TCE exposure. In contrast, ET-1, KLF2 and NOS-3 remain largely unchanged after 800 ppb TCE exposure for 24 hrs relative to PBS. The data demonstrate that the 8 ppb levels of exposure to TCE perturb marker expression to a greater extent than 800 ppb exposure.

Figure 1.

A pooled sample of 20 Whole Hearts were collected after 24hr exposure of TCE at 8 ppb and 800 ppb. Real-time PCR results for Endothelin-1 (ET-1), Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 (NOS3) and Krüppel Like Factor 2 (KLF2). ET-1 was unchanged while both NOS3 and KFL2 where significantly reduced at 8 ppb TCE exposure but not at 800 ppb (*** = p-value < 0.001).

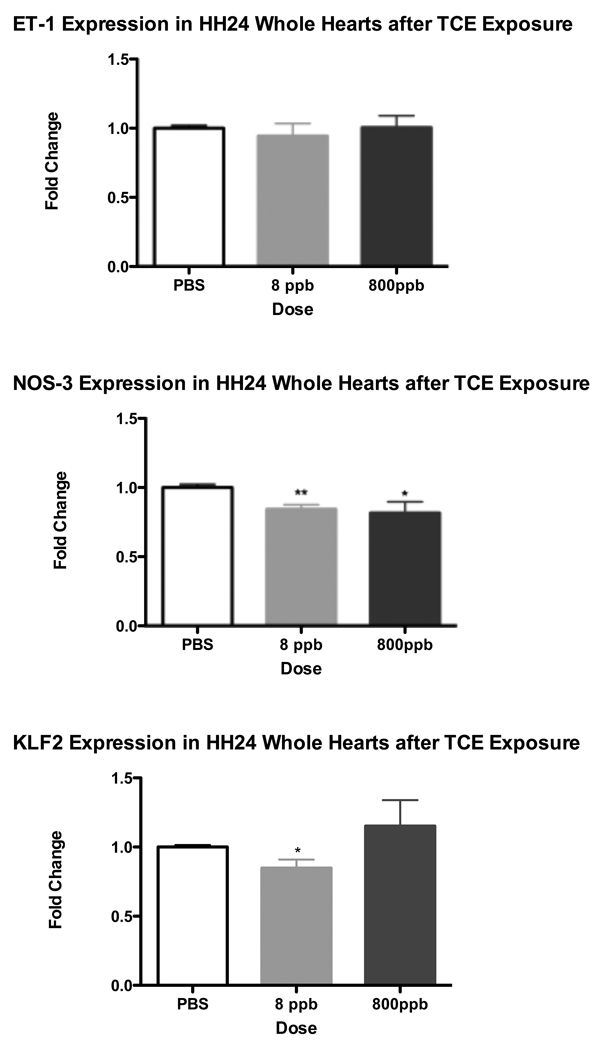

To determine whether the shear stress marker genes demonstrate sustained transcriptional regulation by TCE, additional avian embryos were dosed at HH13, and allowed to develop for a further 48 hrs, at which time, whole heart tissue was extracted and processed for RNA isolation. Both NOS-3 and KLF2 had modest but significant decreases in expression with the longer exposure at both exposure levels. There was a lesser but still significant decrease in NOS-3 after 800 ppb TCE exposure (Fig 2). As with the shorter exposure, ET-1 expression does not significantly change after 8 ppb or 800 ppb TCE exposure when compared to the PBS Control. Since both NOS-3 and KLF2 appeared to be the most responsive at the 8 ppb TCE dose, all subsequent experiments were done using 8 ppb TCE dosage.

Figure 2.

HH24 Whole Hearts were collected after 48hr exposure of TCE at 8 ppb and 800 ppb. Real-time PCR results for Endothelin-1 (ET-1), Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 (NOS3) and Krüppel Like Factor 2 (KLF2). ET-1 was unchanged while NOS3 was significantly reduced at both 8 ppb and 800 ppb TCE exposure. Additionally KLF2 was significantly reduced only after 8 ppb TCE exposure (** = p-value < 0.01; * = p-value < 0.05).

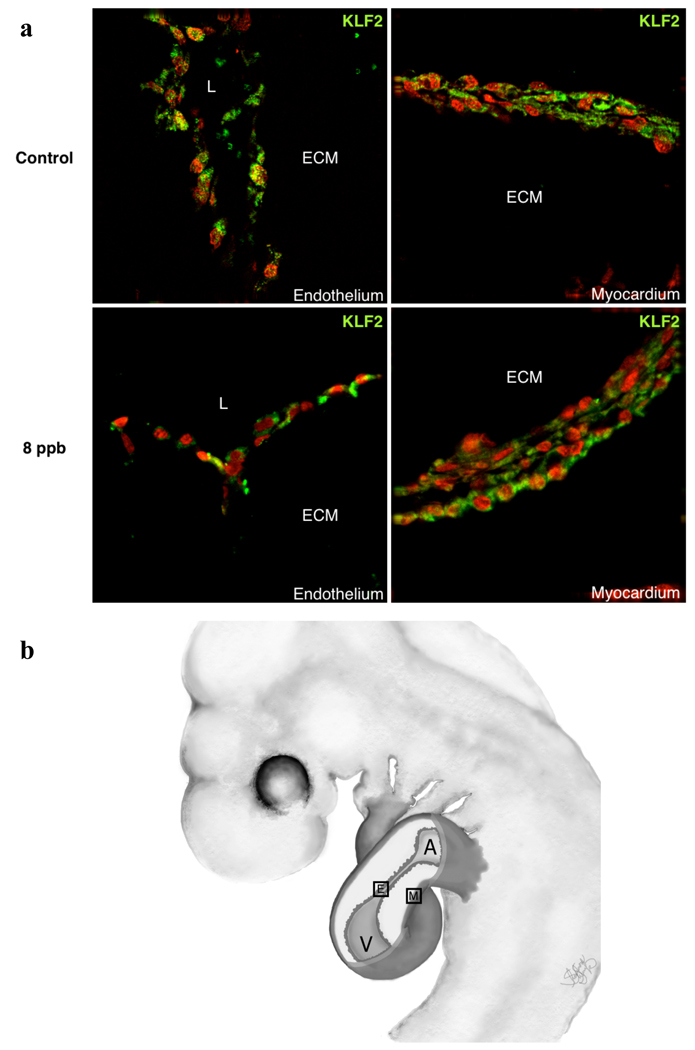

KLF2 Transcription factor protein expression

While KLF2 expression is widely recognized in endothelial cells as a marker of shear stress, it has been reported in cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts and stem cells (Groenendijk et al. 2007; Cullingford et al. 2008). Relatively little is known of its localization in the developing embryo. Work by Groenendijk et al., (2004) showed, by radioactive in situ hybridization, localization of transcripts to the endothelial cells of the AV canal and outflow tract where flow in the heart is most constricted. There was an indeterminate amount of label over the myocardium due to the noise inherent in the radioactive protocol. To verify the expected distribution in the heart, we stained sections of treated and control hearts with an antibody against KLF2. This antibody was verified in a western blot as recognizing a single molecule of the expected size in embryonic heart cell lysates (data not shown). As shown in Figure 3, KLF2 protein is found in endothelial cells of the AV canal as well as mesenchyme and myocardial cells. Though protein expression was not strongly reduced in TCE-treated samples, there appeared to be a more specific diminution in the endothelia.

Figure 3.

KLF2 Antibody Expression in HH17 Whole Hearts collected after approximately 24hr exposure of 8 ppb TCE. KFL2 Antibody expression can be observed in both the endothelium and myocardium of the developing chick heart in both the control and 8 ppb TCE treated samples. Staining in TCE-treated endothelia appears to show an increase in extra-nyclear distribution of the protein.

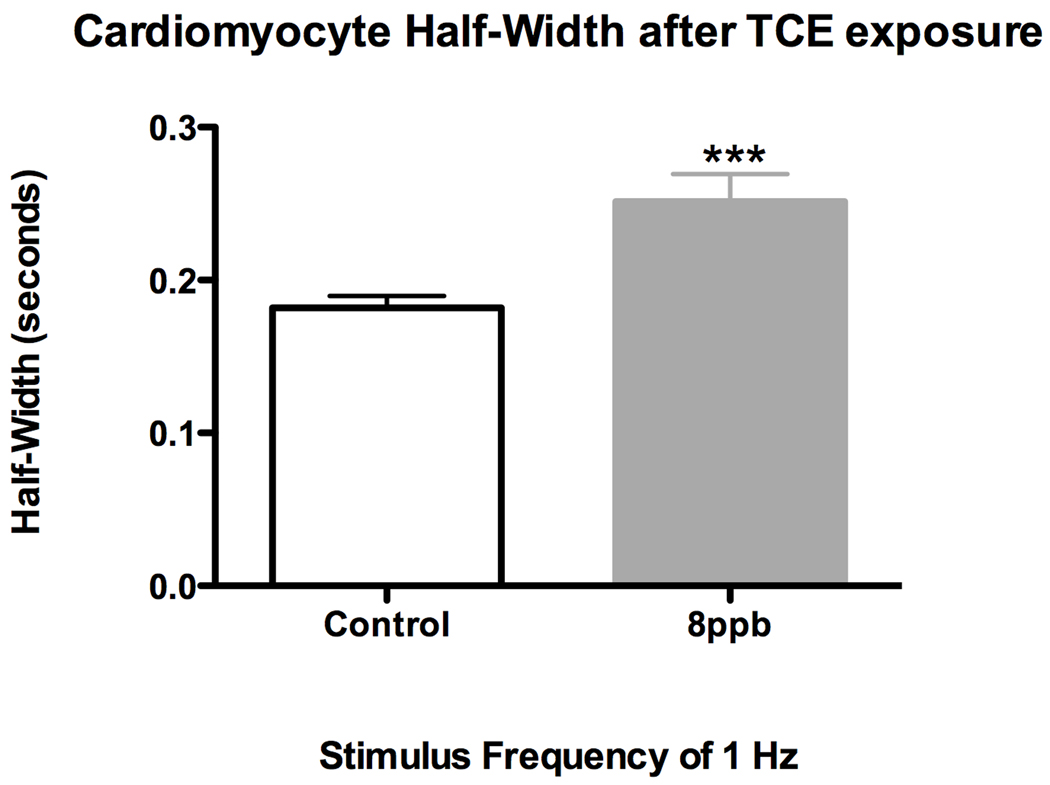

Altered Half-Width after TCE Exposure

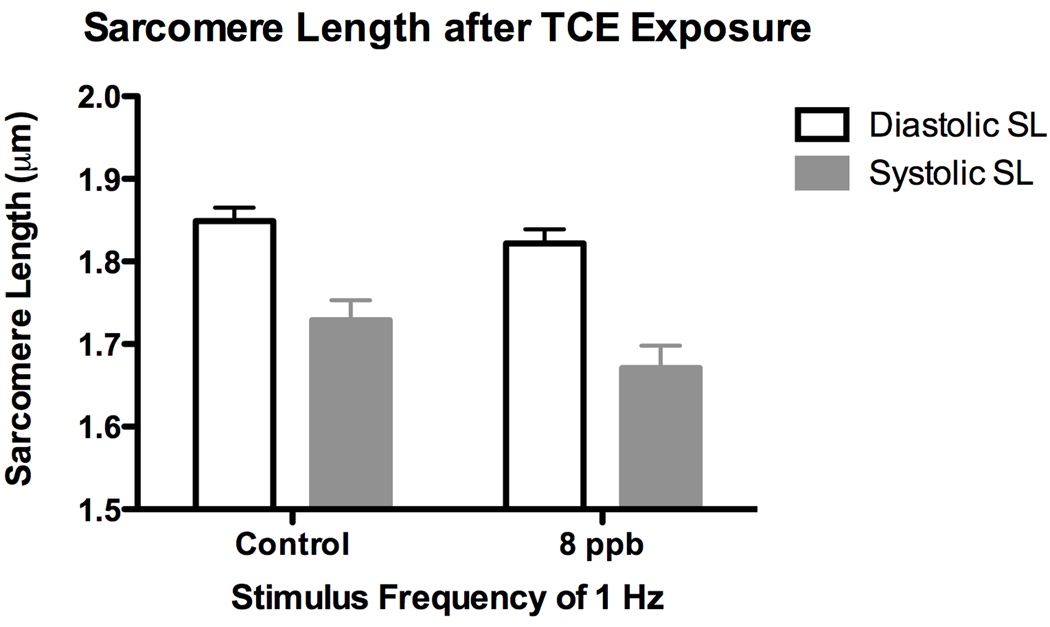

We previously showed (Caldwell et al. 2008), using H2c9 rat cardiomyocyte cells, a reduced flux of calcium after vasopressin stimulation in TCE-treated cells. Experiments showing reduced levels of shear stress markers are consistent with a reduction in cardiac function but do not show it directly. To investigate changes in myocyte contraction directly, we dosed developing embryos at stage 13 with TCE and incubated them until embryonic day 18. Cardiomyocytes were then isolated from the hearts of these embryos by a published protocol (Li et al. 1997; O'Connell et al. 2007) and then directly measured during contraction in vitro. Cells from exposed and control embryos were paced at 60 hz and imaged to measure sacromere parameters during contraction. Cells from embryos exposed to 8 ppb TCE demonstrated a significant increase in the half-width of the rate of contraction when compared to control embryos (Fig 4). This increase in half-width reflects a reduced rate of contraction and is characteristic of reduced cytosolic calcium (Ren et al. 2007). It was observed that the relaxed sarcomere length was unchanged, providing support for the idea that the functional effects resulting from TCE exposure are most likely a result of altered Ca2+ regulation rather than a morphological change to sarcomere structure (Fig 5).

Figure 4.

Half Width of isolated E18 cardiomyocytes exposed to 8 ppb TCE relative to contol cardiomyocytes. Half-width of TCE exposed cardiomyoctes is significantly increased when compared to control cardiomyoctes (*** = p-value < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Sarcomere Length of isolated E18 cardiomyocytes exposed to 8 ppb TCE relative to control cardiomyocytes. Sarcomere length is unchanged by TCE exposure.

Discussion

The prevalence of TCE as a common soil and water contaminant requires a better understanding of the consequences of environmental exposure. While TCE has been implicated in other health effects, the most significant developmental problem appears to be a relationship to congenital heart defects. For reasons that have not been entirely clear, TCE is remarkably cardiac-specific as a teratogen (Goldberg et al. 1990; Yauck et al. 2004; Research Council (U.S.) 2006). The heart is unique in the developing embryo in that it’s function is required even as it is still undergoing morphogenesis. The mechanism explored here, that perturbation of calcium homeostasis in developing myocytes alters contraction and produces morphological consequences provides an explanation for this specificity.

While there are other potential mechanisms for TCE-mediated teratology, the chain of logic suggesting an perturbation of function extends from the initial observation that Serca2 expression was significantly reduced in rat embryo hearts after in utero exposure to TCE (Collier, Selmin et al. 2003). Subsequent studies using an in vitro culture model of mouse embryonal carcinoma P19 cells, showed that low level exposure to TCE perturbed expression of additional calcium homeostatic molecules (Selmin et al. 2008). The embryonic heart requires the regulated release and uptake of intracellular calcium for both function and growth. We reasoned that a perturbation of calcium handling and storage would compromise the ability of the heart to contract normally. Groenendijk et al. (2005), using a venous clip model, showed that reduced blood flow in the heart produced cardiac defects. Thus, the apparent heart-specific teratogenic effects of TCE might be due to a compromise in cardiac function as a critical stage of heart development. Though previous studies explored TCE-mediated teratology in the chick (Loeber and Runyan 1990), the studies of Drake and colleagues established that low-dose TCE could be introduced into the chick embryo by injection into the yolk and calculated exposures that could be related to environmental exposure (Drake et al. 2006; Drake et al. 2006a). Importantly, for the mechanistic hypothesis, Drake and colleagues observed a reduction in aortic blood flow in embryos exposed to low-dose 8 ppb TCE (Drake et al. 2006).

The first test of this hypothesis was an in vitro exposure of a rat cardiomyocyte cell line to low levels of TCE (Caldwell et al. 2008). Though these cells are not spontaneously contractile in culture, they demonstrate a calcium flux when exposed to vasopression. A relatively brief exposure to low levels of TCE produced an approximately 40% reduction in peak calcium as well as reduced release and uptake of calcium as measured by Fura2 fluorescence. The data was consistent with the loss of Serca2a and Ryr2 expression observed with these cells.

To explore changes in cardiac contraction in the intact embryo we turned to molecular markers of function. Groenendijk et al. (2005) showed that expression of shear stress markers in the heart provided a useful measure of changes in cardiac blood flow. We examined the expression of these same shear stress markers ET-1, NOS-3 and KLF2 in heart RNA extracts after injection of TCE in ovo. TCE exposure resulted in the significant decrease of KLF2 and NOS-3 mRNA expression in both the HH17 and HH24 whole heart. As the reduced expression of these markers in the heart was previously seen with venous ligation, the data are consistent with the idea that flow is reduced in the heart as well as in the dorsal aorta. Reduced cardiac function is consistent with this observation.

We show in this paper that the KLF2 marker is expressed in both the endothelium and the myocardium of the developing heart. Although, not quantitative, the images shown in Fig. 3, suggest that KLF2 expression is both reduced in level and extra-nuclear in TCE-exposed endothelium compared to controls. There may also be a reduction in expression in the myocardium, but the pattern suggests that KLF2 expression is retained in the most epicardial layer of the myocardium. It seems likely that the PCR measurement of KLF-2 reflects changes in both cell types found in the early heart. A potential consequence of the reduction of the transcription factor KLF2 is that this transcription factor is developmentally relevant in modulating vascular development through binding to an ETS family protein member ERG to activate Flk1 expression during vascular development (Meadows et al. 2009). Thus, a decrease in KLF2 expression by TCE may function to alter endothelial development.

Of the three potential endothelial markers, we observed no significant changes in ET-1. Groenendijk et al. (2005) identified ET-1 as modestly elevated by a reduction in flow but we found no such effect. Discussions with the laboratory that made this observation suggest that ET-1 is somewhat variable and is not as useful as a marker of flow (Robert Poelman, personal communication).

While the expression of flow markers is altered by TCE exposure, it is only an indirect measure of the hypothesized mechanism. These studies were extended to look at the effect of TCE on myocyte function. Myocytes were isolated from TCE-exposed and control embryos on day E18 and the response to a stimulated contraction was measured. Using the sarcomere half-width of contraction rate as a measure of Ca2+ handling, we observed that 8 ppb TCE is sufficient to significantly increase cardiomyocyte half-width relative to control (Fig. 4). We did not observe a change in sarcomere length indicating that the half-width response observed was not a consequence of a TCE induced sarcomere damage but most likely a result of a TCE induced alteration of Ca2+ handling. The cells were collected at E18, 16 days after in ovo injection and although effects on markers showed some recovery at stage 24 relative to stage 17, the data clearly show that the loss of cardiac function persists in the embryo through the majority of the developmental period.

One issue highlighted by these studies is the dose-response effect. One of the major criticisms of human and animal data has been the apparent inconsistency in dose response (Dugard 2000; Fisher et al. 2001; Hardin et al. 2005). The data reported here show substantially greater perturbation of molecular markers at 8 ppb than at 800 ppb. This is consistent with a number of previous studies. Molecular measures described here are consistent with the functional observations of Caldwell et al. (2008) and Drake et al. (2006; 2006a). Recent studies of gene expression in a H9c2 cells found a biphasic response with maximum effects between 10–100 ppb and again at 10–100 ppm when they measured changes in calcium homeostasis (Caldwell et al. 2008). We previously observed that 50–250 ppm TCE inhibited mesenchymal cell formation in vitro while Drake et al. observed that 8ppb exposure induced proliferation of these cells in ovo (Boyer et al. 2000; Drake et al. 2006). Differences between loss of cushion tissue mesenchyme at higher doses and a proliferation of cushion mesenchyme suggests an ability to perturb differing developmental pathways at different doses. TCE is a volatile compound that rapidly partitions into headspace above tissue culture media or the plastic of culture dishes and it has been difficult to work with low doses. In the studies of Mishima and colleagues (2006) they found a loss of 2/3 of the originally dosed TCE after only 1 hour in doses ranging from 25–250 ppm. Mishima et al. reported that TCE was reduced to undetectable levels after 24 hours (2006). While the kinetics of loss in the egg are unknown, the deficits produced during in ovo exposure argue both for the toxicity of TCE at specific stages and that it is retained long enough to have an effect. Clearly, we observe significant effects in this animal model near the MCL for exposure while the effects of TCE on markers of function are less severe at higher doses. The dose response parameters of TCE remain to be explained and are an important component in evaluating the public health consequences of TCE exposure. We speculate that an aspect of detoxification or compartmentalization of TCE in cells or tissues is involved, but further work needs to be done to resolve the issue.

Together, the data presented here are consistent with previous data suggesting that cardiac development is sensitive to low dose TCE exposure. Calcium channel genes were seen to be down-regulated by TCE and this produced an alteration in calcium homeostasis in cultured myocytes. Markers of shear stress were shown to reflect changes in cardiac blood flow (Groenendijk et al. 2005). In this study we found these same markers to demonstrate reduced flow in the TCE-treated heart and that TCE produces a change in the rate of contraction. Ongoing studies will evaluate whether the metabolism of TCE is responsible for the unusual dose sensitivity seen in these and previous studies.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the American Heart Association (AHA #0810020Z) and NIH ES006694. We would like to thank Dr. Robert E. Poelmann for the real-time PCR primer sequences used in this publication. We would also like to thank Shannon Shoemaker for drawing Fig. 3b. In addition, we would like to thank Dr. Paul Krieg and Matthew Salanga for the KLF2 antibody used in this publication. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. André L. Tavares and Carlos M. Moran for their guidance and support.

Bibliography

- Boyer AS, Finch WT, et al. Trichloroethylene inhibits development of embryonic heart valve precursors in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2000;53(1):109–117. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/53.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell PT, Thorne PA, et al. Trichloroethylene disrupts cardiac gene expression and calcium homeostasis in rat myocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2008;104(1):135–143. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JM, Selmin O, et al. Trichloroethylene effects on gene expression during cardiac development. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67(7):488–495. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullingford TE, Butler MJ, et al. Differential regulation of Krüppel-like factor family transcription factor expression in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes: effects of endothelin-1, oxidative stress and cytokines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(6):1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake VJ, Koprowski SL, et al. Cardiogenic effects of trichloroethylene and trichloroacetic acid following exposure during heart specification of avian development. Toxicol Sci. 2006;94(1):153–162. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake VJ, Koprowski SL, et al. Trichloroethylene exposure during cardiac valvuloseptal morphogenesis alters cushion formation and cardiac hemodynamics in the avian embryo. Environ Health Perspect. 2006a;114(6):842–847. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugard PH. Effects of trichloroethylene (TCE) on an in vitro chick atrioventricular canal culture. Toxicol Sci. 2000;56(2):437–438. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.2.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JW, Channel SR, et al. Trichloroethylene, trichloroacetic acid, and dichloroacetic acid: do they affect fetal rat heart development? Int J Toxicol. 2001;20(5):257–267. doi: 10.1080/109158101753252992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SJ, Lebowitz MD, et al. An association of human congenital cardiac malformations and drinking water contaminants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16(1):155–164. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BC, Hierck BP, et al. Development-related changes in the expression of shear stress responsive genes KLF-2, ET-1, and NOS-3 in the developing cardiovascular system of chicken embryos. Dev Dyn. 2004;230(1):57–68. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BC, Hierck BP, et al. Changes in shear stress-related gene expression after experimentally altered venous return in the chicken embryo. Circ Res. 2005;96(12):1291–1298. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171901.40952.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BC, Van der Heiden K, et al. The Role of Shear Stress on ET-1, KLF2, and NOS-3 Expression in the Developing Cardiovascular System of Chicken Embryos in a Venous Ligation Model. Physiology (Bethesda, Md) 2007;22:380–389. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00023.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin BD, Kelman BJ, et al. Trichloroethylene and dichloroethylene: a critical review of teratogenicity. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73(12):931–955. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogers B, DeRuiter MC, et al. Unilateral vitelline vein ligation alters intracardiac blood flow patterns and morphogenesis in the chick embryo. Circ Res. 1997;80(4):473–481. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PD, Goldberg SJ, et al. Threshold of trichloroethylene contamination in maternal drinking waters affecting fetal heart development in the rat. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(3):289–292. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, McNelis MR, et al. Hyperplasia and hypertrophy of chicken cardiac myocytes during posthatching development. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(2 Pt 2):R518–R526. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.2.R518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber CP, Runyan RB. A comparison of fibronectin, laminin, and galactosyltransferase adhesion mechanisms during embryonic cardiac mesenchymal cell migration in vitro. Dev Biol. 1990;140(2):401–412. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SM, Salanga MC, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 cooperates with the ETS family protein ERG to activate Flk1 expression during vascular development. Development. 2009;136(7):1115–1125. doi: 10.1242/dev.029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima N, Hoffman S, et al. Chick embryos exposed to trichloroethylene in an ex ovo culture model show selective defects in early endocardial cushion tissue formation. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76(7):517–527. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell TD, Rodrigo MC, et al. Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;357:271–296. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-214-9:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page C, Check I, et al. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Case Studies in Environmental Medicine (CSEM) Trichloroethylene Toxicity. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Li Q, et al. Cardiac overexpression of antioxidant catalase attenuates aging-induced cardiomyocyte relaxation dysfunction. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128(3):276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Council (U.S.) N. Assessing the Human Health Risks of Trichloroethylene: Key Scientific Issues. The National Academies Press. 2006:425. [Google Scholar]

- Selmin O, Thorne PA, et al. Trichloroethylene and trichloroacetic acid regulate calcium signaling pathways in murine embryonal carcinoma cells p19. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2008;8(2):47–56. doi: 10.1007/s12012-008-9014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yauck JS, Malloy ME, et al. Proximity of residence to trichloroethylene-emitting sites and increased risk of offspring congenital heart defects among older women. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70(10):808–814. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]