Abstract

Although school-based programming is an important element of the effort to curb tobacco use among young people, a comprehensive tailored curriculum has not been available for deaf and hard of hearing youth. The authors describe the drafting of such a program by expert educators, and findings from a test of the curriculum using a quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group design involving four schools for the deaf in three states. Two schools received the curriculum and two served as non-curriculum controls. Survey data were collected from students in grades 7–12 at baseline and at the start and end of three school years, from 511 to 616 students at each time point, to assess tobacco use, exposure to tobacco education, and tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes and practices. Changes within each school were assessed as the difference between the baseline survey and the average of the last four follow-up surveys. Current (past month) smoking declined significantly at one intervention school (22.7% baseline to 7.9% follow-up, p=.007) and current smokeless tobacco use at the other (7.5% baseline to 2.5% follow-up, p=.03). Exposure to tobacco prevention education, and anti-tobacco attitudes and knowledge each increased significantly at one or both schools. One control school experienced a significant decline in tobacco education exposure (p<.001) and an increase in anti-tobacco attitudes (p=.01). Despite limitations, this study supports that a tailored tobacco prevention curriculum can increase perceived exposure to anti-tobacco education and have a significant impact on tobacco-related practices, attitudes and knowledge among deaf and hard of hearing youth.

Keywords: Tobacco prevention deaf youth, Tobacco education deaf youth, Tobacco use among deaf and hard of hearing youth

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use, the single most preventable cause of death in the nation, most frequently begins during childhood and adolescence, and progresses to regular long-term smoking because of rapid addiction (US. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 1994. Although rates of cigarette smoking are declining, there is evidence of considerable smoking among young people, and smoking prevention remains a critically important public health concern (Nelson, Mowery, Asman, Pederson, O’Malley, Malarcher, Mailbach, & Pechacek, 2008; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2000).

School-based anti-tobacco education is an important element in the overall effort to curb tobacco use among young people (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007). However, appropriately tailored programming has not been available for all youth, including the over half million deaf and hard of hearing students receiving special education services in the United States (Mitchell, 2004; U.S. Department of Education, 2002; Zehler, Fleischman, Hopstock, Pendzick, & Stephenson, 2003). This is a concern in that evidence suggests that there is awareness of tobacco products and considerable tobacco use in this population, but that access to incidental anti-tobacco messages in clinical and other settings is limited (Berman, Streja, Bernaards, Eckhardt, Kleiger, Maucere, Wong, Barkin, & Bastani, 2007; Berman, Bernaards, Eckhardt, Kleiger, Maucere, Streja, Wong, Barkin, & Bastani, 2006; Tamaskar, Malia, Stern, Gorenflo, Meador, & Zazove; 2000). This culturally and linguistically distinct population uses American Sign Language (ASL), a language which is visual/spatial/gestural with its own grammar, morphology, and syntax, other signed languages, and other modes of communication including signed or spoken English. For many deaf persons, English is a second language, and, on average, high school graduates read English on a fourth grade reading level (Gallaudet Research Institute, 1996; Holt, Traxler, & Allen, 1997). Deaf and hard of hearing children and teenagers frequently face issues relating to delayed social development, social acceptance and stigmatization, self-esteem, communication problems, and difficulties when it comes to school performance (Padden & Humphries 1988; 2005; Lane, Hoffmeister, & Bahan, 1996; Titus, Schiller, & Guthmann, 2008; Guthmann & Graham, 2004; Kluwin, Stinson, & Colarossi, 2002), predictors of youthful tobacco use in the general population (Nelson et al., 2008; Baker, Brandon & Chassin, 2004; Flay, 1993; Conrad, Flay, & Hill, 1992; Chassin, Presson, & Sherman, 2005.

This paper describes research conducted to develop and test a tailored tobacco prevention curriculum for deaf and hard of hearing children and adolescents. A quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group design that included four schools for the deaf in three states was utilized. Two schools received the curriculum (intervention condition) and two schools served as non-curriculum controls. We report student outcomes in terms of exposure to tobacco prevention education, rates of tobacco use, tobacco-related attitudes and tobacco-related knowledge.

METHODS

Program Development

A collaboration was established between educators at the California School for the Deaf Fremont (CSDF), one of California’s two schools for the deaf, and researchers at the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Research, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Public Health and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. Educators from the Marie H. Katzenbach School for the Deaf (Trenton, NJ) joined the CSDF/UCLA group to craft the program. To identify appropriate program and survey content, and study procedures, the research team: reviewed tobacco education materials available for hearing youth and curriculum for deaf youth in other subject areas; drew on findings from surveys conducted among 467 deaf high school and college students, and in-depth signed interviews with a subset of these young people (Berman et al., 2006; Berman et al., 2007; Berman, Eckhardt, Kleiger, Wong, Lipton, Bastani, & Barkin, 2000); conducted semi-structured interviews with educators in California, an open-ended survey among volunteer faculty at CSDF, and a survey of 166 faculty at the four schools for the deaf participating in this study to identify programming requirements; obtained recommendations from focus groups conducted among parents, faculty, and junior and senior high students at a program for deaf and hard of hearing youth not included in the main study; and received critical feedback of curriculum drafts from a national panel of expert educators.

Curriculum

Utilizing these steps, the research team developed “Hands Off Tobacco! An Anti-Tobacco Program for Deaf Youth,” a school-based curriculum for grades 7–12 (extended to grades 5 and 6 following the study, at faculty request)(Sternfeld, Barnabei, Kriger, Guthmann, Lester, Berman, Maxwell, & Wong, 2004). The curriculum includes seven lessons at each grade level focusing (appropriately for age and grade) on: the health effects of tobacco use (and second hand smoke exposure); addiction; industry marketing and youth manipulation; anti-tobacco efforts and social action to change smoking norms and patterns; self-esteem and self-concept; the influence of friends and peers; and decision making. The curriculum features: an evidence-based life-skills approach (Botvin, 2000; Botvin & Griffin, 2007); emphasis on visual elements, graphic design, and hands-on activities; use of images of deaf and hard of hearing youth and examples from the lives of deaf and hard of hearing students; appropriate pacing of material, repetition of basic concepts, and simple language usage; use of interactive teaching strategies including role-play, art and art therapy techniques; emphasis on communication between school, family and (where appropriate) the school-based living unit; and recommendations for home, school-wide and community activities. Homework and classroom worksheets are provided. The content is appropriate for implementation in a range of classroom settings (e.g., health, social studies, science, etc.); can be used to illustrate concepts in a range of subject areas (e.g., math, history); and delivery of each lesson can be used in one or more classroom sessions as necessary.

Program Implementation

Four schools for the deaf in three states were recruited to participate in the quasi-experimental study evaluating the curriculum. Two schools received the curriculum and two schools served as non-curriculum controls. At all schools faculty were advised of the research and a program coordinator was appointed to facilitate data collection. At the intervention schools the coordinator provided support and guidance in all aspects of curriculum implementation and in-service educational sessions were conducted to familiarize faculty with the materials.

Data Collection

Using Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved information sheets and consent procedures, students in grades 7–12 at all schools were invited to participate in the study, which involved completion of student surveys at the start and end of three school years. Informed consent was obtained from students and parents or guardians. The survey time points were baseline (Fall 2004), prior to program implementation, and five follow-up time points (Spring and Fall 2005, Spring and Fall 2006, and Spring 2007). Initially, the plan was to administer the survey in school or grade-level assemblies using written questionnaires and answer sheets, with translation of each item into ASL. However, despite focus group testing in two schools for the deaf not participating in the main study, completing the survey proved difficult for many students, and small group administration allowing for one-on-one faculty assistance was implemented. A deaf, trained research team member, fluent in ASL, conducted the surveys at each school, assisted by faculty members. A $5.00 gift, determined by the school administration, was given to participating students at each time point.

Instruments

The California Student Tobacco Survey (WestEd), which evaluates the state of California tobacco education program, was used, with permission, as the basis for the 90-item student survey (McCarthy, Dietsch, Hanson, Zheng, & Aboelata, 2004). Modifications were made in the instrument to include items relating to deafness, increase clarity and ease of translation into ASL, and to eliminate items that focus group participants considered confusing or complex for deaf or hard of hearing students. The survey included items on demographic and deafness characteristics, exposure to tobacco prevention education, tobacco- related knowledge, attitudes and practices, exposure to tobacco industry marketing, and exposure to anti-tobacco messages.

Measures

All variables used in the analyses, including tobacco knowledge, attitudes and practices, exposure to tobacco prevention and control programming, demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), grade and deafness characteristics, were measured using student responses to survey items and are thus based on self-report. The outcome variables were tobacco education exposure score, anti-tobacco attitude score, tobacco-related knowledge score, current and ever cigarette smoking, and current and ever smokeless tobacco use.

Tobacco education exposure score

We measured exposure to tobacco prevention and control programming using a composite score based on responses to five survey items: (1) “In the past year did you practice ways to say NO to tobacco in any of your classes?” (Yes = +1, No = −1, Not sure = 0); (2) “In the past year, which of the following did you have at school? Circle all the apply: (a) “School lessons about tobacco use; (b) A hearing guest speaker talk about tobacco use; (c) A deaf/hard of hearing guest speaker talk about tobacco use; (d) A school assembly or event about tobacco use; (e) A DARE program that talked about cigarettes.” (+1 point for each); (3) “In the past year, did any of your teachers or counselors talk about any of the following? Circle all that apply (a) The reasons why people your age smoke; (b) How many people your age smoke; (c) The effects of cigarette smoking on your body; (d) The effects of secondhand smoke; (e) How to feel good about yourself; (f) How to make good decisions about behaviors such as smoking.” (+1 point for each); (4) “Has what you learned in school in the past year helped you feel it is okay to say ‘NO’ to friends who offer you cigarettes?” (Yes = +1, No = −1, Not sure = 0, Did not learn anything in school about smoking = −1); (5) “Was the information you received in school in the past year helpful to you in making decisions about tobacco use?” (Yes = +1, No = −1, Not sure = 0, Did not learn anything in school about smoking = −1). Raw scores, which ranged from −3 to 14, were converted to a scale of 0–100 using the transformation 100×(raw score − lower bound)/range. Higher scores indicate greater perceived exposure to tobacco prevention and control programming.

Anti-tobacco attitude score

We constructed an anti-tobacco attitude score using responses to five survey items: (1) “Young people who smoke cigarettes have more friends”; (2) “Smoking cigarettes makes young people look cool or fit in;” (3) “It is safe to smoke for only a year or two, as long as you quit after that;” (4) “Young people risk hurting their health if they smoke from 1 to 5 cigarettes per day;” (5) “I will lose non-smoking friends if I smoke cigarettes.” Items 1–3 were scored as Yes = −1, No = 1, and Not sure = 0; items 4–5 were scored as Yes = 1, No = −1, and Not sure = 0. Raw scores were converted to a scale of 0–100 using the transformation described above. Higher scores indicate a more negative attitude towards tobacco use.

Tobacco-related knowledge score

We constructed a tobacco-related knowledge score using responses to twelve survey items: (1) “Smoking cigarettes makes teeth yellow;” (2) “Smoking cigarettes makes people smell bad;” (3) “Smokers live shorter lives than non-smokers;” (4) “Smoking cigarettes can make asthma worse;” (5) “The smoke from other people’s cigarettes is harmful to you;” (6) “People can get addicted to using tobacco just like they can get addicted to using other drugs such as cocaine or heroin;” (7) “A pregnant woman can harm her unborn baby if she smokes cigarettes;” (8) “Breathing smoke from someone else’s cigarettes – secondhand smoke – can cause lung cancer;” (9) “Smoking cigarettes can hurt your health even if you do not inhale;” (10) “Teenagers are too young to get addicted to cigarettes;” (11) “Nicotine is the only harmful substance in tobacco;” and (12) “Young people can keep from getting addicted to cigarettes by not inhaling when they smoke.” Items 1–9 were scored as Yes = +1, No = −1, and Not sure = 0; items 10–12 were scored as Yes = −1, No = 1, and Not sure=0. Raw scores were converted to a scale of 0–100 using the transformation described above. Higher scores indicate higher knowledge.

Current cigarette smoking was assessed as any cigarette smoking in the past month. Current smokeless tobacco use was similarly assessed as any smokeless tobacco use in the past month. Ever tried cigarette smoking and ever tried smokeless tobacco were also assessed as binary measures.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted SAS Version 9.1 for Windows (Copyright (c) 2002–2003 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

We compared baseline demographic and deafness characteristics across schools using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

Because of the quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group design, for outcome analyses, we conducted comparisons across time within school rather than comparisons between schools. We did not consider across-school statistical analyses to be appropriate because of the extent to which the student bodies at the participating schools varied in demographic and deafness characteristics. Initially the plan was to track students’ survey responses on an individual basis across time points and conduct longitudinal analyses modeling change in the responses of individual students over time. Tracking codes involving parents’ first and last initials and student birthdates were used to maintain anonymity, required because of the inclusion of items regarding practices that are illegal and/or against school rules. Although successfully implemented in focus groups, during the actual study students did not successfully replicate tracking information provided at baseline at later time points. Thus the responses of individual students could not be linked across time points in the analyses. This necessitated analyzing the data as cross-sectional. Hence we compared baseline to each follow-up time point within each school using two-sample t-tests for continuous outcomes (tobacco education exposure score, anti-tobacco attitude score, tobacco-related knowledge score) and chi-square tests for binary outcomes (current and ever cigarette smoking). In addition, in order to obtain a single estimate of change over time within each school for each outcome, we computed mean change as the difference between the baseline mean and the average of the responses at the last four time points. Since there were approximately four times as many follow-up responses as baseline responses, we gave each follow-up observation a weight of ¼ in these analyses to make the effective samples sizes for computing the baseline mean and four time point follow-up mean approximately equal. This strategy avoided underestimating the standard error for the follow-up mean and thus overstating the statistical significance of the difference. These analyses omitted the second time point as transitional. For continuous outcomes, analyses of mean change were conducted using weighted analyses in the SAS MEANS procedure. For binary outcomes, analyses of change were conducted using Fisher exact tests (current and ever smokeless tobacco use) or chi-square tests (current and ever cigarette smoking) with weights in the SAS FREQ procedure. All P values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 provides the number of students participating in the study as a proportion of enrollment. New enrollees and graduation changed the subject pool through time. Some students were excluded by the school administration from participation because of cognitive impairment. School absence, field trips and other events also resulted in some students not taking part at some time points.

Table 1.

Enrollment and percentage of students grades 7–12 participating by school and survey time point

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2004 | Fall 2005 | Spring 2006 | Fall 2006 | Spring 2007 | ||||||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| Intervention School 1 | 103/124 | 83 | 79/123 | 64 | 71/123 | 58 | 93/131 | 71 | 100/131 | 76 |

| Intervention School 2 | 220/270 | 82 | 162/272 | 60 | 218/272 | 80 | 212/264 | 80 | 221/264 | 84 |

| Control School 1* | 212/259 | 82 | 201/252 | 80 | 192/280 | 69 | 167/210 | 80 | 153/232 | 66 |

| Control School 2† | 83/113 | 74 | 69/90 | 77 | 68/90 | 76 | 86/107 | 80 | 53/107 | 50 |

n = number of surveys received, N= enrollment provided by school

Separate enrollment numbers provided for fall and spring of each year. All other schools provided annual enrollment.

Enrollment provided by school includes grade 6 students, who were not eligible to participate in the survey. The actual percentages of students participating is therefore higher than the percentages reported here.

Table 2 provides demographic and deafness characteristics of the student participants at baseline. There were no significant differences among the four schools with regard to gender distribution, proportion of students in middle and high school grades, or age of becoming deaf or hard of hearing. There were significant differences in age, with Intervention School 1 having older students. Intervention School 1 also had the highest proportion of students who identified themselves as the only deaf person in their family (73%, 75/103). The racial/ethnic distribution of students differed among the schools, with Control School 2 having predominantly white students (83%, 69/83) while the other schools were more ethnically diverse. Control School 2 also had the highest proportion of students whose friends were all or almost all deaf (70%, 58/83).

Table 2.

Demographic and deafness characteristics of student participants at baseline

| Intervention School 1 | Intervention School 2 | Control School 1 | Control School 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students completing survey | N = 103 | N = 220 | N = 212 | N = 83 | |

| Age (mean ± std) | 16.0 ± 2.2 | 15.1 ± 2.0 | 15.5 ± 1.9 | 15.6 ± 1.8 | .002 |

| Age categories | .03 | ||||

| 11–13 y | 14 (13%) | 44 (21%) | 34 (16%) | 13 (16%) | |

| 14–17 y | 62 (60%) | 143 (68%) | 147 (70%) | 56 (67%) | |

| 18–21 y | 27 (26%) | 24 (11%) | 30 (14%) | 14 (17%) | |

| Gender (% Male) | 53 (51%) | 113 (53%) | 103 (49%) | 39 (47%) | .78 |

| Grade level | .84 | ||||

| Middle school (grades 7–8) | 21 (20%) | 45 (21%) | 51 (24%) | 19 (23%) | |

| High school (grades 9–12) | 82 (80%) | 169 (79%) | 160 (76%) | 64 (77%) | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||

| Asian | 7 (7%) | 12 (5%) | 11 (5%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Black/African | 37 (36%) | 37 (17%) | 15 (7%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 (14%) | 51 (23%) | 93 (44%) | 3 (4%) | |

| White | 32 (31%) | 80 (36%) | 55 (26%) | 69 (83%) | |

| Other/Mixed | 13 (13%) | 40 (18%) | 38 (18%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Age of D/HH | .37 | ||||

| Born | 55 (53%) | 118 (54%) | 116 (55%) | 46 (55%) | |

| < 2 | 12 (12%) | 21 (10%) | 29 (14%) | 16 (19%) | |

| 2–5 | 15 (15%) | 25 (11%) | 32 (15%) | 8 (10%) | |

| ≥ 6 | 4 (4%) | 8 (4%) | 5 (2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (17%) | 48 (22%) | 30 (14%) | 12 (14%) | |

| Friends deaf | .04 | ||||

| All/almost all | 55 (53%) | 118 (54%) | 101 (48%) | 58 (70%) | |

| About half | 33 (32%) | 60 (27%) | 72 (34%) | 18 (22%) | |

| Not a lot/None | 15 (15%) | 42 (19%) | 39 (18%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Only deaf person in family | .02 | ||||

| (% Yes) | 75 (73%) | 123 (56%) | 125 (59%) | 55 (66%) |

Statistical tests for differences among the four schools were conducted using analysis of variance for continuous variables (age) and chi-square tests for categorical variables (all other variables). All P values are two-sided.

Exposure to anti-tobacco education

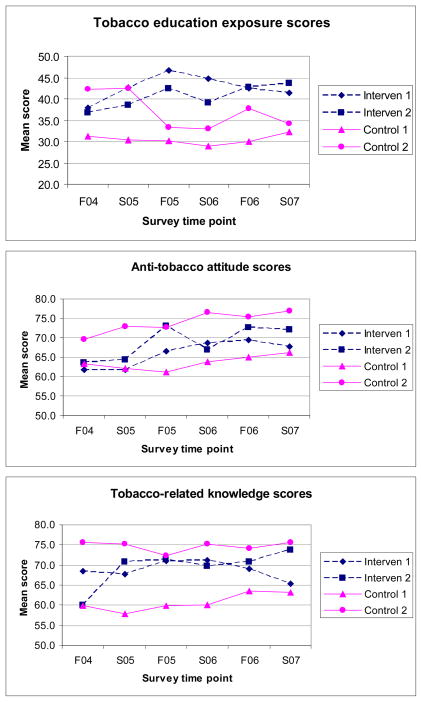

Trends in student self-report of exposure to tobacco education are shown in Figure 1, with results of statistical analyses provided in Table 3. At baseline, students at each of the two intervention schools had mean tobacco education exposure scores of about 37 points; the mean for Control School 1 was about 6 points lower, while the mean for Control School 2 was about 6 points higher. Students at both intervention schools had significant increases in tobacco education exposure scores from baseline to follow-up, with mean increases of over 5 points. Students at Control School 2 had a significant decrease in mean tobacco education exposure score of 7.7 points. Students at Control School 1 had no change.

Figure 1.

Time trends in tobacco education exposure, anti-tobacco attitude and tobacco-related knowledge scores*

*F04, S05, F05, S06, F06, S07: Fall 2004, Spring 2005, Fall 2005, Spring 2006, Fall 2006, Spring 2007

Table 3.

Tobacco education exposure, anti-tobacco attitude, and tobacco-related knowledge scores*

| A. Baseline mean (95% CI) | B. Follow-up mean (last four time points) (95% CI) | C. Mean change (95% CI) | D. P value, A vs. B | E. Follow-up time points different from baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco education exposure scores | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 37.9 (33.4, 42.4) | 43.6 (41.2, 46.1) | +5.7 (1.4, 10.1) | .01 | F05, S06 |

| Intervention School 2 | 36.8 (33.6, 40.0) | 41.9 (40.4, 43.4) | +5.1 (2.3, 7.9) | <.001 | F05, F06, S07 |

| Control School 1 | 31.2 (28.6, 33.9) | 30.2 (28.8, 31.7) | −1.0 (−3.5, 1.5) | .44 | |

| Control School 2 | 42.3 (37.8, 46.8) | 34.6 (31.9, 37.2) | −7.7 (−12.3, −3.2) | <.001 | F05, S06, S07 |

| Anti-tobacco attitude scores | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 61.7 (57.1, 66.4) | 68.0 (65.7, 70.4) | +6.3 (2.0, 10.6) | .004 | S06, F06 |

| Intervention School 2 | 63.7 (61.3, 66.2) | 71.0 (69.6, 72.5) | +7.3 (4.9, 9.7) | <.001 | F05, S06, F06 |

| Control School 1 | 63.3 (60.4, 66.1) | 63.8 (62.3, 65.3) | +0.6 (−2.1, 3.3) | .68 | |

| Control School 2 | 69.6 (65.0, 74.3) | 75.3 (72.9, 77.7) | +5.6 (1.2, 10.0) | .01 | S06, S07 |

| Tobacco-related knowledge scores | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 68.4 (65.2, 71.5) | 68.9 (67.0, 70.8) | +0.5 (−2.6, 3.7) | .74 | |

| Intervention School 2 | 60.1 (57.7, 62.4) | 71.5 (70.4, 72.6) | +11.4 (9.3, 13.5) | <.001 | F05, S06, F06, S07 |

| Control School 1 | 59.8 (57.3, 62.3) | 61.5 (60.1, 62.9) | +1.7 (−0.7, 4.1) | .17 | |

| Control School 2 | 75.7 (72.4, 79.0) | 74.2 (72.4, 75.9) | −1.5 (−4.7, 1.6) | .35 | |

Baseline mean (Column A) is the average of responses in Fall 2004, prior to the intervention. Follow-up mean (Column B) is the average of responses in Fall 2005, Spring 2006, Fall 2006 and Spring 2007. All computations involving follow-up time points (Columns B, C and D) used weighted means and variances, in which responses at baseline were given a weight of 1 and responses at each of the last four follow-up time points were given a weight of ¼, thus making the effective sample sizes for the baseline-follow-up comparison approximately equal. Column E identifies follow-up time points that were significantly different from baseline at P<.05 by two-sample t-tests (unweighted). All P values are two-sided. For all scores, the range of possible values is 0–100.

Attitudes

Mean anti-tobacco attitude scores were similar among the four schools at baseline, ranging from 62–70 points. The intervention schools experienced significant improvement in attitude scores from baseline to follow-up of 6.3 and 7.3 points. Control School 1 had no change and Control School 2 also had a significant increase, of 5.6 points.

Knowledge

Mean tobacco-related knowledge scores at baseline ranged from about 60 points at Intervention School 2 and Control School 1 to 76 points at Control School 2. Intervention School 2 has a significant increase of 11.4 points. No significant change was detected at the other schools.

Tobacco use

Trends in student self-reported tobacco use are presented in Figure 2, with results of statistical analyses presented in Table 4. At baseline, Intervention School 1 had the highest levels of current cigarette smoking among its students, with 22.7% reporting smoking within the past month. This school had a dramatic decline of 14.8%, with a 7.9% rate of current smoking at follow-up. Current smoking at baseline was lowest at Intervention School 2, with 9.6% of student respondents reporting smoking in the past month. This school had a non-significant drop of 2.1% at follow-up. At baseline, Control Schools 1 and 2 reported intermediate rates of current smoking of 11.1% and 14.6%, respectively. These schools had small decreases in current smoking rates that were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Time trends in current and ever smoking and smokeless tobacco use*

*F04, S05, F05, S06, F06, S07: Fall 2004, Spring 2005, Fall 2005, Spring 2006, Fall 2006, Spring 2007

Table 4.

Self-reported tobacco use practices*

| A. Baseline percent (95% CI) n/N | B. Follow-up percent (last four time points) (95% CI) n/N | C. Change in percent (95% CI) | D. P value, A vs. B | E. Follow-up time points different from baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any cigarette smoking in past month | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 22.7 (14.4, 31.0) 22/97 | 7.9 (2.1, 13.8) 26/328 | −14.8 (−24.9, −4.6) | .007 | S06, F06, S07 |

| Intervention School 2 | 9.6 (5.6, 13.6) 20/209 | 7.4 (3.8, 11.1) 59/793 | −2.1 (−7.5, 3.3) | .44 | |

| Control School 1 | 11.1 (6.8, 15.6) 22/197 | 9.3 (4.9, 13.7) 63/678 | −1.9 (−8.1, 4.3) | .56 | |

| Control School 2 | 14.6 (7.0, 22.3) 12/82 | 13.3 (5.0, 21.7) 34/255 | −1.3 (−12.6, 10.0) | .82 | |

| Ever tried cigarette smoking | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 37.9 (28.5, 47.2) 39/103 | 18.5 (10.3, 26.8) 63/340 | −19.3 (−31.8, −6.9) | .004 | F05, F06, S07 |

| Intervention School 2 | 24.7 (18.9, 30.4) 53/215 | 24.3 (18.4, 30.2) 196/808 | −0.4 (−8.7, 7.9) | .93 | |

| Control School 1 | 26.2 (20.2, 32.1) 55/210 | 19.7 (13.8, 25.5) 140/711 | −6.5 (−14.8, 1.8) | .13 | S06 |

| Control School 2 | 41.0 (30.4, 51.3) 34/83 | 34.4 (22.7, 46.0) 88/256 | −6.6 (−22.3, 9.1) | .41 | |

| Any smokeless tobacco use in past month | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 3.2 (0.1, 9.1) 3/93 | 1.9 (1.4, 7.9) 6/316 | −1.3 (−6.0, 3.4) | .59 | |

| Intervention School 2 | 7.5 (4.0, 12.4) 13/174 | 2.5 (0.8, 6.1) 18/712 | −4.9 (−9.5, −0.4) | .03 | F05, S06, F06, S07 |

| Control School 1 | 3.9 (1.6, 7.9) 7/178 | 4.3 (1.7, 8.9) 27/621 | −0.4 (−3.9, 4.7) | .85 | |

| Control School 2 | 6.2 (2.0, 13.8) 5/81 | 4.7 (0.9, 13.6) 11/236 | −1.5 (−9.0, 6.0) | .70 | |

| Ever tried smokeless tobacco | |||||

| Intervention School 1 | 6.9 (2.8, 13.6) 7/105 | 5.3 (1.6, 12.5) 18/337 | −1.5 (−8.4, 5.3) | .67 | |

| Intervention School 2 | 7.5 (4.3, 12.1) 15/199 | 5.3 (2.6, 9.4) 42/796 | −2.3 (−7.1, 2.6) | .36 | S07 |

| Control School 1 | 6.3 (3.4, 10.6) 13/205 | 7.3 (3.9, 12.2) 51/701 | 0.9 (−4.2, 6.0) | .72 | |

| Control School 2 | 19.3 (11.4, 29.4) 16/83 | 13.0 (5.9, 23.8) 33/254 | −6.3 (−18.1, 5.6) | .31 | S07 |

Baseline percent is the percent of affirmative responses in Fall 2004, prior to the intervention. Follow-up percent is the weighted average of the percent of affirmative responses in Fall 2005, Spring 2006, Fall 2006 and Spring 2007. All computations involving follow-up time points (Columns B, C and D) used weights, in which responses at baseline were given a weight of 1 and responses at each of the last four follow-up time points were given a weight of ¼, thus making the effective sample sizes for the baseline-follow-up comparison approximately equal. Comparison of baseline to follow-up was conducted using chi-square tests (any cigarette smoking past month, ever tried cigarette smoking) and Fisher exact tests (any smokeless tobacco use in past month, ever tried smokeless tobacco). Column E identifies follow-up time points that were significantly different from baseline at P<.05 by chi-square tests (unweighted). All P values are two-sided.

Rates of ever trying cigarette smoking showed a similar pattern. Intervention School 1 had the highest rates at baseline (37.9%), and experienced a drop of 19.3% to 18.5% at follow-up. Intervention School 2 has the lowest rates of ever smoked at baseline, and showed no change at follow-up. Control School 1 had a decrease of 6.5% that was marginally significant, and Control School 2 had a non-significant decrease of 6.6%..

Current use of smokeless tobacco at baseline was relatively high at Intervention School 2 and Control School 2 and relatively low at Intervention School 1 and Control School 1 at baseline. Intervention School 2, which had the highest rate at baseline (7.5%), had a significant drop of 4.9%. The other three schools had smaller declines that were not statistically significant. Rates of ever trying smokeless tobacco did not change significantly from baseline to follow-up at any of the schools.

DISCUSSION

School-based tobacco education is well accepted as an important tobacco use prevention strategy, and deaf youth describe schools as the best place in which to reach this population with tobacco prevention messages (Berman et al., 2006; Berman et al, 2007). Nevertheless, research points to the absence of adequate programming for this population, and that schools for the deaf lag behind in provision of anti-tobacco educational programs. This is of concern in that there is considerable self-reported ever-smoking in this population, albeit less than reported for hearing youth (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman & Schulenberg, 2008), and transition out of the protective deaf school educational setting may result in increased risk-taking behavior, including tobacco use, among deaf young adults (Berman et al., 2006; Berman et al., 2007; Schildroth, Rawlings, & Allen, 1991). Nearly 40% of respondents at the start of the study reported living with a smoker, and nearly a third reported pressure to smoke, predictive of smoking uptake and shift to regular tobacco use among adolescents (Baker, Brandon, & Chassin, 2004; Hoffman, Sussman, Unger, & Valente, 2006).

In light of the importance of tobacco use as a health problem, use of tobacco products among deaf youth, and the lack of tailored tobacco education programming available for deaf youth, findings from our first-ever test of a deaf-friendly educational tobacco prevention program for deaf and hard of hearing youth are encouraging. We obtained positive results with respect to tobacco education exposure, and student attitudes, knowledge and tobacco use. Student reports of exposure to anti-tobacco programming at control schools declined or did not change during the study years, while students at both intervention schools reported a significant increase in exposure. Anti-tobacco attitudes increased significantly at both intervention sites and one control school, with greater change occurring at the schools where students received the educational program. Knowledge regarding the health and other consequences of tobacco use increased at one intervention school but neither control school. At the intervention school where current smoking at baseline was greatest among the four participating schools, a significant decline in tobacco use occurred.

Limitations of the Study

This study attempted to address the tobacco use of deaf and hard of hearing youth by developing and testing a deaf-friendly school based tobacco prevention curriculum. In doing so, the study has a number of limitations. First, including only schools for the deaf in our study facilitated implementation of the program and data collection, and allowed us to consider the program’s impact on a fairly large number of deaf and hard of hearing youth. However, limiting our study to these settings leaves unanswered the question of how we could implement our program in the diverse mainstream environments where an increasing proportion of deaf and hard of hearing youth receive their education (Holden-Pitt, & Diaz, 1998; American Annals of the Deaf, 2007). Second, even among schools for the deaf there are considerable variations in the size and composition of the student body with implications for the ways in which our program could be tested. Each state in the United States has at most one or two schools for the deaf and it was not possible to exactly match participating schools on the basis of student demographic and other characteristics. Of particular note, the four schools in our study had different distributions of race/ethnicity among the students, which is important considering that Latino and White adolescents are known to have higher rates of cigarette smoking than African-American or Asian teenagers youth (Johnston et al, 2008). Third, although participation rates were high, the shifting student population resulting from new enrollments, graduation and changes in participation at various follow up time points, and the unexpected failure in tracking responses for individual students, limited the ability to evaluate progression of individual perceptions, practices and knowledge across time. Fourth, although student privacy was maintained in data collection, the need to shift to smaller groups and greater involvement by faculty than initially intended when administering the surveys, and the tight-knit community of students and teachers in deaf school settings, does raise some concern about the possible unwillingness of students to candidly report tobacco and other substance use.

Finally, intervention school administrators were unwilling to require that faculty implement the curriculum; teachers did so as they saw fit. At Intervention School 2, school administration required that, in the first year, the program be delivered as an after-school voluntary activity as part of the school’s life skills program; in the second and third year it was included as part of regular health and physical education classroom activities. At Intervention School 1, the program was implemented as part of the health curriculum during all three years. Differences in declines in current and ever smoking between the two intervention schools may relate to this difference in implementation. It may also reflect that fewer teachers were involved in the program at School 2 than School 1, or that there was greater opportunity for a decline in smoking at School 1 because of higher raters of reported smoking at baseline.

Teachers were asked, but not required, to report how many and which program elements were implemented, and to complete a brief assessment of each lesson utilized. Faculty comments regarding the curriculum were extremely favorable. Anecdotal evidence, lesson assessments that were completed, and end-of-study group debrief of participating teachers suggested that selected lessons and curriculum elements were implemented successfully. However, there was no evidence of “incidental” use of the program to illustrate points in the context of math, history or other subject areas. A more detailed accounting of program implementation would improve the understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the program, patterns of uptake, and how the program should be modified to increase its utility.

Despite these challenges and shortcomings, evidence from this first-ever program of research regarding tobacco education in deaf schools is promising. Compared to baseline, at one or both schools where the curriculum was available, students reported increased exposure to tobacco prevention education, increased tobacco-related knowledge, improved attitudes, and reduced current smoking and smokeless tobacco use. These changes were not observed at the control schools. We consider these results to be particularly impressive because the program was not uniformly or even extensively adopted and integrated into the overall curriculum of the participating intervention schools. Likely, the impact could have been even greater if this integration had taken place.

Next steps

Following completion of the study, we provided the curriculum to the control sites and made this program available, at no cost, to any educator serving this population. The curriculum was publicized through articles targeting educators of deaf and hard of hearing youth, by word-of-mouth, made available through a center where educators seek out classroom materials, and described at meetings of educators and public health professionals (e.g., Berman & Guthmann, 2006–2007; Berman, Guthmann, & Streja, 2006; Guthmann & Berman, 2007; Guthmann & Berman, 2006). About two dozen copies of the program materials have been requested and distributed.

A substantial body of research has been conducted to identify elements of effective tobacco prevention programming for hearing youth (USDHHS, 1994; USDHHS, 2000; Skara & Sussman, 2003). The absence of appropriate, tailored materials for deaf youth may, in part, result from the fact that this population has not often been included in such research, a reflection of the significant barriers to data collection in this population (Barnett & Franks, 1999; Lipton, Goldstein, Fahnbulleh, & Gertz, 1996; Olson, 1999; Hendershot, 1999; Jones, Mallinson, Phillips, & Kang, 2006). Research is now needed to find out, first, what impact the anti-tobacco program would have on students’ exposure, knowledge, attitudes and practices if the program modules were fully and completed implemented in the educational programming of schools for the deaf. Second, we need to learn what impact the program would have among deaf and hard of hearing youth who receive their education in mainstream settings alongside hearing peers. Finally, increasing attention is being paid to conducting research into how health and other educational programs, once crafted and found to have an impact on health-related outcomes through intervention studies, can be widely and successfully disseminated. With respect to our work, research is needed to find out how to best disseminate tobacco prevention education curricula to teachers of deaf and hard of hearing youth and their students, and how to fine-tune such programs to encourage their uptake, implementation and maintenance once they are in the hand of these educators. This research is needed not only with respect to reaching children and adolescents in deaf residential and day school programs, but to reach students in mainstream settings where a great many of the nation’s deaf and hard of hearing youth receive their education, as well.

Information regarding the curriculum is available on the Minnesota Chemical Dependency Program for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Individuals website (http://mncddeaf.org/pages/materials.htm). If you are interested in obtaining a copy of the curriculum please contact Dr. Debra S. Guthmann, Director of Pupil Services, California School for the Deaf, Fremont at dguthmann@csdf-cde.ca.gov, or by phone at (510) 794-3684. Copies of the curriculum are free except for the cost of shipping.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Tobacco Related Diseases Research Program (TRDRP), University of California [10GT-3101, 12HT-3201 to B.A.B and D.S.G] and the National Institutes of Health [CA0106042 to C.M.C]. We wish to express our appreciation to the faculty, staff, students and their parents at the California School for the Deaf, Fremont (Fremont, California), the Marie H. Katzenbach School for the Deaf (Trenton, New Jersey), The California School for the Deaf, Riverside (Riverside, California), the Minnesota State Academy for the Deaf (Fairbault, Minnesota); and the Orange County Department of Education Regional Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Program, University High School, Irvine, California for their participation in this study. We also wish to thank: Cynthia B. Sternfeld, Ed.S., LPC, Susan M. Barnabei, B.S., Karen Krieger, B.S., Frank Lester, M.S.W., Annette E. Maxwell, Dr.P.H., Glenn C. Wong, M.P.H, Linda Oberg, M.S., M.A.; Sook Hee Choi, M.A., Chriz Dally, MA, Janet Dickinson, Ph.D., Thomas Holcomb, Ph.D., Nancy Moser, LCSE, Katherine A. Sandberg, B.S., CCDCR, and Jon Levy, for their participation in the development and testing of the curriculum.

The research was conducted with full approval by the UCLA Office for Protection of Human Subjects, Institutional Review Board (UCLA OPRS IRB) #G03-07-033-13.

Contributor Information

Barbara A. Berman, Email: bberman@ucla.edu, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Research, School of Public Health and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Los Angeles, Room A2-125 CHS, 650 Charles Young Drive South, Box 956900, Los Angeles, California 90095-6900, USA, Phone: (310) 794-9283, FAX: (310)206-3566.

Debra S. Guthmann, Email: dguthmann@csdf-cde.ca.gov, California School for the Deaf, Fremont, 39350 Gallaudet Drive, Fremont, California 94538, USA, Phone: (510) 794-9283, FAX: (510) 794-3653.

Catherine M. Crespi, Email: ccrespi@ucla.edu, Department of Biostatistics, UCLA School of Public Health, Box 951772, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772, USA, Ph: 310-206-9364, FAX: 310-206-3566.

Weiqing Liu, Email: weiqing@ucla.edu, Department of Biomathematics, University of California, Los Angeles, AV-118 CHS, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA, (310) 794-7322, FAX: (310) 267-2611.

References

- American Annals of the Deaf. Eductional programs for deaf students. Schools and programs in the United States. American Annals of the Deaf. 2007;152(2):105–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Brandon TH, Chassin L. Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S, Franks P. Telephone ownership and deaf people: implications for telephone surveys. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1754–1756. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman BA, Bernaards C, Eckhardt EA, Kleiger HB, Maucere L, Streja L, Wong G, Barkin S, Bastani R. Is tobacco use a problem among deaf college students? American Annals of the Deaf. 2006;151(4):441–451. doi: 10.1353/aad.2006.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman BA, Eckhardt EA, Kleiger HB, Wong GC, Lipton DS, Bastani R, Barkin S. Developing a tobacco survey for deaf youth. American Annals of the Deaf. 2000;145:245–255. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman BA, Guthmann DS. Anti-tobacco school-based programming for deaf youth. Odyssey. Gallaudet University Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center. 2006–2007;8(1):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Berman BA, Guthmann DS, Streja L. School-based tobacco control programming for deaf and hard-of-hearing youth. Paper presented at: American Public Health Association; Boston. 2006. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Berman BA, Streja L, Bernaards CA, Eckhardt EA, Kleiger HB, Maucere L, Wong G, Barkin S, Bastani R. Do deaf and hard of hearing youth need anti-tobacco education? American Annals of the Deaf. 2007;152(3):344–355. doi: 10.1353/aad.2007.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Preventing drug abuse in schools: social and competence enhancement approaches targeting individual-level etiologic factors. Review. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(6):887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW. School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and Other drug use. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19(6):607–615. doi: 10.1080/09540260701797753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs – 2007. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2007. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ. Adolescent cigarette smoking: a commentary and issues for pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30(4):299–303. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KM, Flay BR, Hill D. Why children start smoking cigarettes: predictors of onset. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87(12):1711–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR. Youth tobacco use: risks, patterns, and control. In: Orleans CT, Slade J, editors. Nicotine addiction: Principles and management. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaudet Research Institute. Form S, Norms Booklet for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students (Including Conversions of Raw Score to Scaled Score & Grade Equivalent and Age-based Percentile Ranks for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students) 9. Gallaudet University; Washington, DC: 1996. Stanford Achievement Test. [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann D, Graham V. Substance abuse: a hidden problem within the D/deaf and hard of hearing communities. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2004;3(1):49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann D, Berman BA. School-based tobacco control programming for deaf and hard of hearing youth. Paper presented at: ADARA (American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association) National Biennial Conference, Coming Full Circle: Deaf Service Past, Present and Future; 1966–2007; Saint Louis. 2007. May, [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann D, Berman BA. School-based tobacco control programming for deaf or hard of hearing youth. Paper presented at: Gallaudet University Regional Centers Conference: Deaf and Hard of Hearing Adolescents: Leaving No One Behind; Memphis. 2006. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot GE. Session on deaf respondents in health interview surveys. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association; Chicago. 1999. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BR, Sussman S, Unger JB, Valente TW. Peer influences on adolescent cigarette smoking: a theoretical review of the literature. Subsance Use and Misuse. 2006;41:103–155. doi: 10.1080/10826080500368892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden-Pitt L, Diaz AJ. Thirty years of the Annual Survey of Deaf and Hard-of –Hearing Children and Youth: a glance over the decades. American Annals of the Deaf. 1998;143(2):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JA, Traxler CB, Allen TE. Interpreting the Scores: A User’s Guide to the 9th Edition Stanford Achievement Test for Educators of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students, Gallaudet Research Institute Technical Report 97-1. Gallaudet University; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Various stimulant drugs show continuing gradual declines among teens in 2008, most illicit drugs hold steady. University of Michigan News Service; Ann Arbor, MI: Dec 11, 2008. Retrieved 04/20/2009 from http:www.monitoringthefuture.org. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Mallinson RK, Philips L, Kang Y. Challenges in language, culture, and modality: translating English measures into Americn Sign Language. Nursing Research. 2006;55(2):75–81. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluwin T, Stinson M, Colarossi G. Social processes and outcomes of in-school contact between deaf and hearing peers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2002;7(3):200–213. doi: 10.1093/deafed/7.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane H, Hoffmeister R, Bahan B. A journey into the Deaf world. San Diego, CA: Dawn Sign Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton DS, Goldstein MF, Fahnbulleh FW, Gertz EN. The Interactive Video-Questionnaire: A new technology for interviewing deaf persons. American Annals of the Deaf. 1996;141(5):370–378. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy WJ, Dietsch B, Hanson TL, Zheng CH, Aboelata M. Evaluation of the In-School Tobacco Use Prevention Education Program 2001–2002. Sacramento, California: Tobacco Control Section, California Department of Health Services; p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE. National profile of deaf and hard of hearing students in special education from weighted survey results. American Annals of the Deaf. 2004;149:336–349. doi: 10.1353/aad.2005.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Mowery P, Asman K, Pederson LL, O’Malley PM, Malarcher A, Mailbach EW, Pechacek TF. Long-term trends in adolescent and young adult smoking in the United States: metapatterns and implications. American Journal of Public Health. 98:905–915. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L. The National Immunization Survey: Development of strategies to include Deaf respondents in an RDD telephone survey. Paper presented at: American Public Health Association; Chicago. 1999. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Padden CA, Humphries TL. Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Padden CA, Humphries TL. Inside Deaf Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schildroth A, Rawlings B, Allen T. Deaf students in transition: education and employment issues for Deaf adolescents. Volta Review. 1991;93(5):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Skara S, Sussman S. A review of 25 long-term adolescent tobacco and other drug use prevention program evaluations. Review. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(5):451–474. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld CB, Barnabei SM, Kriger K, Guthmann DS, Lester F, Berman BA, Maxwell AE, Wong GC. Hands off Tobacco! An Anti-Tobacco Program for Deaf Youth. 2004. A curriculum developed through funding from TRDRP, the Tobacco Related Diseases Research Program, University of California (Grants #10GT-3101, 12HT-3201, Barbara A. Berman, Ph.D., Principal Investigator, UCLA; Debra S. Guthmann, Ed.D., Principal Investigator, California School for the Deaf, Fremont) [Google Scholar]

- Tamaskar P, Malia T, Stern C, Gorenflo D, Meador H, Zazove P. Preventive attitudes and beliefs of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9(6):518–525. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.6.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus J, Schiller JA, Guthmann D. Characteristics of youths with hearing loss admitted to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2008;13(3):336–350. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enm068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Twenty-fourth annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, D.C: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zehler AM, Fleischman HL, Hopstock PJ, Pendzick ML, Stephenson TG. Descriptive study of services to LEP students and LEP students with disabilities (Special topic report #4: Findings on special education LEP students) Arlington, VA: Development Associates, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]