Abstract

Background

The course of depression from pregnancy to 1 year post partum and risk factors among mothers and fathers are not known.

Aims

(1) To report the longitudinal patterns of depression from the third trimester of pregnancy to 1 year after childbirth; (2) to determine the gender differences between women and their partners in the effect of psychosocial and personal factors on postpartum depression.

Methods

A longitudinal cohort study was carried out over a consecutive sample of 769 women in their third trimester of pregnancy and their partners attending the prenatal programme in the Valencian Community (Spain) and follow-up at 3 and 12 months post partum. The outcome variable was the presence of depression at 3 or 12 months post partum measured by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Predictor variables were: psychosocial (marital dissatisfaction, confidant and affective social support) and personal (history of depression, partner's depression and negative life events, depression during the third trimester of pregnancy) variables. Logistic regression models were fitted via generalised estimating equations.

Results

At 3 and 12 months post partum, 9.3% and 4.4% of mothers and 3.4% and 4.0% of fathers, respectively, were newly diagnosed as having depression. Low marital satisfaction, partner's depression and depression during pregnancy increased the probability of depression during the first 12 months after birth in mothers and fathers. Negative life events increased the risk of depression only among mothers.

Conclusions

Psychosocial and personal factors were strong predictors of depression during the first 12 months post partum for both mothers and fathers.

Keywords: Depressive disorder, pregnancy, gender, mothers, fathers, risk factors, depression, gender inequalities

Introduction

Women, especially women of child-bearing age, are at high risk of depression. Evidence suggests that postpartum depression can be part of a continuum, with onset of illness during pregnancy.1 However, the course of depression during the first year post partum and the risk factors are not known, mainly because most research has only assessed depression on a single occasion, only taking into account a follow-up period covering the first few months post partum.2 Moreover, most attention has been paid to the problem of postpartum depression among women, and paternal postpartum depression is a relatively unrecognised phenomenon.3

Recent studies on symptoms of women's depression across the transition from pregnancy to the postpartum period show considerable stability in the incidence of depression, despite a decrease in symptoms from pregnancy to post partum.4 5 However, these rates vary across studies depending on factors such as time of assessment, definition of depression, instrument used to measure depression, and the cultural characteristics of the population studied.6 7

The scientific literature has highlighted the influence of personal and psychosocial risk factors (history of depression, stressful life events, low social support, marital problems) during pregnancy on postpartum depression.3 8–14 However, most studies have used a cross-sectional design. In addition, only a limited number of studies have looked at the risk factors for fathers' depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period, but a meta-analysis has shown that maternal depression is a strong predictor of postpartum depression among fathers.3

Despite the existence of several studies that have assessed the evolution of depression among mothers along the first year of life of their last born child and the risk factors, few studies have included large samples of mothers and fathers with the aim of identifying gender differences, if any, in the pattern of depression and risk factors during the first year after childbirth. Therefore this study has two aims: (a) to report the longitudinal patterns of depression incidence from the third trimester of pregnancy to 1 year after childbirth; (b) to determine gender differences between women and their partners in the effect of psychosocial (marital dissatisfaction, social support) and personal (history of depression, negative life events, pregnancy depression and partner's depression) factors on depression during the first year post partum.

Methods

Study design and setting

A longitudinal cohort study was carried out on a sample of women selected by consecutive sampling from January to December 2005. A total of 769 women in their third trimester of pregnancy (phase I), between 28 and 31 weeks of pregnancy, and their partners attending the prenatal programme in 10 primary care centres of the Valencian Community (Spain) were recruited into the study. In the Valencian community, almost 80% of pregnant women are assisted by primary healthcare midwives, within the prenatal programme (only pregnancies at high obstetric risk are lost, as these cases are under a hospital follow-up protocol), since the Spanish Health System is universal and free. The socio-demographic profile of our sample is similar to the general population of women of the same reproductive age, the only difference being 2% more of foreign women. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant, who had received a letter explaining the purposes of the study. Response rates were 89.3% for women and 87.0% for men, providing a sample of 687 and 669 subjects, respectively. After initial participation at phase I, a postal questionnaire was sent at 3 months post partum (phase II) and another one at 12 months post partum (phase III). The participation rate at these two phases was 74.9% and 75.9% (phase II) and 69.7% and 70.6% (phase III) for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Outcome variable

Depression at phase I, II and III was assessed with the validated Spanish version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), using a threshold score of 12/13.15 This validation has not determined the cut-off score for fathers, so, as Matthey et al16 suggested, a two-point-lower cut-off score (≥11) was used. The outcome variable was the presence of depression at either phase II or III.

Predictor variables

Psychosocial variables

Two variables were analysed (marital satisfaction and social support). They were measured at phase I and II. Marital satisfaction was measured with the ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale (10 items)17 adapted to a Spanish cultural context (translation and back-translation). Each item was rated on a four-point scale. The internal consistency of this scale was 0.93. The total score was categorised into high (>24 for women, >25 for men) and low (≤24 for women, ≤25 for men) from the values obtained in a k-means clustering technique, using squared Euclidean distance.

The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (11 items) validated for Spain18 19 was used to measure functional elements of social support. This 11-item questionnaire has two subscales: (a) affective social support (four items) to measure positive affective expressions; (b) confidant social support (seven items), including social functions such as a confidant relationship. Each item was rated on a five-category Likert format. The internal consistency of these two subscales was 0.79 and 0.88, respectively. Both subscales were dichotomised into high and low, taking the 15th centile as the cut-off point.

Personal variables

A history of depression (measured at phase I), partner's depression (measured at phase I and II) and negative life events (measured at phase I and II) were included. History of depression was measured with a question about the presence of depression during the 12 months before pregnancy. The indicator presence or absence of unfavourable life events was elaborated using five questions (serious illness or death of a close family member, serious illness or death of a close friend, separation or divorce, partner's loss of job, and serious economical problems); it was considered that a subject had experienced unfavourable life events if at least one of the above events was present. Depression during the third trimester of pregnancy (28–31 weeks of pregnancy) was also included.

Time of data collection

We introduced time of data collection (3 and 12 months post partum) as a potential predictor variable.

Adjusting variables

Some previous studies have shown a relationship between postpartum depression and several personal, socioprofessional factors (age, employment during pregnancy, couple's occupational social class, parity, native country, weekly hours devoted to domestic chores).9 11 20–25 Therefore we included these variables as adjusting factors. Weekly hours devoted to domestic chores were measured at phase I and II. Couples' occupational social class was assigned according to the occupation of the woman or the couple (whichever was higher) and was coded with a widely used Spanish adaptation of the British classification.26 Robertson et al,9 in a systematic evidence-based literature review of risk factors of postpartum depression, showed that obstetric factors, including pregnancy-related complications such as pre-eclampsia, hyperemesis and premature labour, as well as delivery-related complications, such as caesarean section and instrumental delivery, have a small effect on the development of postpartum depression. In our study, we did not adjust these variables because they did not have any significant association with the outcome variable.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the longitudinal relation between psychosocial and personal factors and subsequent postpartum depression. Specifically, we used the generalised estimating equation (GEE) approach for analysing correlated data. In addition, GEE accommodates both time-dependent (marital satisfaction, affective and confidant social support, partner's depression, negative life events and weekly hours devoted to domestic chores) and time-independent (history of depression, employment during pregnancy, couple's occupational social class, parity, native country) covariates. Mothers and fathers who were depressed at the third trimester of pregnancy may have reported psychosocial factors in a negative way. Therefore two models were fitted excluding and including depression during the third trimester of pregnancy as an explanatory variable. Subjects who participated at either phase II or III were included in the analyses. Analyses were conducted using Stata software.

Results

Description of the sample

The distribution of depression during the third trimester of pregnancy and the psychosocial and personal characteristics of the sample are shown in table 1. The prevalence of depression during pregnancy was higher among women (10.3%) than men (6.5%). Among men whose partners were experiencing pregnancy depression, the prevalence of pregnancy depression was 14.5%, and conversely 23.3% of mothers experienced depression during pregnancy when their partners did. The percentage of couples where at least one of the partners experienced depression during pregnancy was 15.1%. The prevalence of psychosocial factors was similar for both sexes. The prevalence of history of depression was lower among men (9.8% vs 21.4%). Concerning socioprofessional factors, percentages were also similar except for age, employment status and domestic chores. Fathers were older and spent less time doing housework.

Table 1.

Depression and psychosocial characteristics measured at the third trimester of pregnancy and personal characteristics of the sample

| Mothers | Fathers | p Value | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Depression during pregnancy* | |||||

| No | 615 | 89.7 | 621 | 93.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 71 | 10.3 | 43 | 6.5 | |

| Psycosocial factors | |||||

| Marital satisfaction | |||||

| High | 407 | 59.7 | 372 | 57.8 | 0.479 |

| Low | 275 | 40.3 | 272 | 42.2 | |

| Affective social support | |||||

| High | 541 | 79.0 | 523 | 79.2 | 0.905 |

| Low | 144 | 21.0 | 137 | 20.8 | |

| Confidant social support | |||||

| High | 568 | 83.2 | 550 | 83.6 | 0.835 |

| Low | 115 | 16.8 | 108 | 16.4 | |

| Personal factors | |||||

| History of depression | |||||

| No | 540 | 78.6 | 598 | 90.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 147 | 21.4 | 65 | 9.8 | |

| Negative life events | |||||

| No | 480 | 69.9 | 401 | 60.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 207 | 30.1 | 262 | 39.5 | |

| Socioprofessional factors | |||||

| Age | |||||

| <30 years | 286 | 41.6 | 154 | 23.0 | <0.001 |

| 30–34 years | 300 | 43.7 | 314 | 46.9 | |

| >34 years | 101 | 14.7 | 201 | 30.0 | |

| Parity | |||||

| Primiparae | 496 | 72.2 | 477 | 71.4 | 0.714 |

| Multiparae | 191 | 27.8 | 192 | 28.7 | |

| Couple's occupational social class | |||||

| Manual workers | 306 | 44.6 | 296 | 44.3 | 0.906 |

| Non-manual workers | 380 | 55.4 | 372 | 55.7 | |

| Employment† | |||||

| No | 143 | 52.0 | 26 | 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 544 | 48.0 | 643 | 96.1 | |

| Native country | |||||

| Not Spain | 74 | 10.8 | 74 | 11.1 | 0.797 |

| Spain | 613 | 89.2 | 595 | 88.9 | |

| Domestic chores (weekly hours) | |||||

| Up to 30 h | 524 | 76.3 | 632 | 96.3 | <0.001 |

| >30 h | 163 | 23.7 | 24 | 3.7 | |

Cut-off value was ≥ 13 for mothers and ≥11 for fathers.

To have paid work during pregnancy in mothers and in fathers at the time of data collection.

Longitudinal patterns of depression from 28 and 31 weeks of pregnancy to 12 months post partum

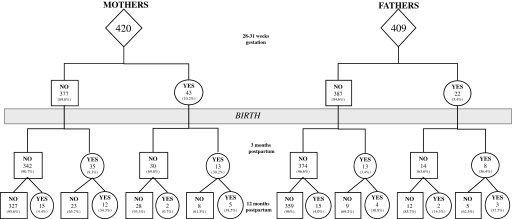

To show these longitudinal patterns, subjects who participated at all of three phases were included, 420 (61.13%) women and 409 (61.14%) men. Figure 1 shows several notable features of depression from 28 and 31 weeks of pregnancy to 12 months post partum. Firstly, most mothers and fathers (77.9% and 87.8%, respectively) reported no increase in depression during this period. Secondly, the layout of the figure also makes possible a calculation of the percentage of women who were newly diagnosed as having depression in the postnatal period. Numbers in circles below the birth line indicate postnatal depression. At 3 months post partum, 9.3% of mothers and 3.4% of fathers were new cases of depression. The corresponding values at 12 months post partum were 4.4% for mothers and 4.0% for fathers. A decrease in the incidence of depression during the 12 months post partum was found among mothers (9.3% vs 4.4%), but the association is at the limit of statistical significance (p=0.074, table 2). However, the incidence of depression remained constant for fathers (3.4% vs 4.0%, p=0.369, table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale) across the three times of measurement. At each row (ie, time of measurement), the sample was divided between those who scored above the cut-off for depression (circle) and those who did not score above the cut-off for depression (square). Values are the number of mothers/fathers in each cell with the percentage with respect to the row above in parentheses.

Table 2.

Association between postpartum depression and psychosocial and personal factors among mothers and fathers

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||||||||||||

| % | p Value | Model 1 | Model 2 | % | p Value | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |||||

| Marital satisfaction | ||||||||||||||||

| High | 6.0 | 1 | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Low | 14.7 | <0.001 | 1.91 | (1.07 to 3.41) | 0.030 | 1.81 | (1.00 to 3.27) | 0.050 | 8.8 | <0.001 | 2.45 | (1.15 to 5.19) | 0.020 | 2.23 | (1.05 to 4.75) | 0.037 |

| Affective social support | ||||||||||||||||

| High | 7.8 | 1 | 1 | 4.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Low | 17.8 | <0.001 | 0.92 | (0.46 to 1.86) | 0.816 | 0.90 | (0.44 to 1.85) | 0.781 | 10.3 | <0.001 | 1.64 | (0.74 to 3.63) | 0.224 | 1.23 | (0.53 to 2.83) | 0.631 |

| Confidant social support | ||||||||||||||||

| High | 7.4 | 1 | 1 | 4.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Low | 22.5 | <0.001 | 1.81 | (0.87 to 3.74) | 0.111 | 1.68 | (0.80 to 3.53) | 0.173 | 10.9 | <0.001 | 1.11 | (0.49 to 2.56) | 0.798 | 1.04 | (0.43 to 2.52) | 0.931 |

| Partner's depression | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 8.4 | 1 | 1 | 4.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 27.8 | <0.001 | 4.18 | (1.95 to 8.96) | <0.001 | 3.40 | (1.78 to 8.53) | <0.001 | 16.3 | <0.001 | 3.09 | (1.43 to 6.66) | 0.004 | 3.61 | (1.57 to 8.26) | 0.002 |

| History of depression | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 7.5 | 1 | 1 | 5.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 18.5 | <0.001 | 1.87 | (1.02 to 3.42) | 0.040 | 1.72 | (0.94 to 3.14) | 0.079 | 8.2 | 0.320 | 1.56 | (0.59 to 4.06) | 0.364 | 1.09 | (0.39 to 3.61) | 0.875 |

| Negative life events | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 7.4 | 1 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 18.3 | <0.001 | 2.10 | (1.20 to 3.68) | 0.009 | 2.12 | (1.20 to 3.74) | 0.009 | 6.8 | 0.203 | 1.09 | (0.56 to 2.10) | 0.804 | 0.86 | (0.43 to 1.73) | 0.671 |

| Time of data collection | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 months post partum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 12 months post partum | 0.65 | (0.39 to 1.08) | 0.096 | 0.61 | (0.36 to 1.05) | 0.074 | 1.08 | (0.60 to 1.94) | 0.793 | 1.36 | (0.69 to 2.76) | 0.369 | ||||

| Baseline depression | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 7.0 | 1 | 3.9 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 32.7 | <0.001 | 2.05 | (1.06 to 3.96) | 0.032 | 33.3 | <0.001 | 21.14 | (9.90 to 45.16) | <0.001 | ||||||

Multivariate results

A total of 503 women and 478 men were included in the multivariate analysis. These samples contributed to 805 and 848 observations in women and men, respectively. The mean number (interquartile range (IQR)) of follow-up observations was 1.6 (IQR 1–2) among women and 1.8 (IQR 1–2) among men. Table 2 shows the incidence of depression at 3 or 12 months post partum according to psychosocial and personal factors and multivariate results. The incidence of depression during 12 months post partum was higher among mothers and fathers with low marital satisfaction (14.7% and 8.8%, respectively), low affective social support (17.8% and 10.3%, respectively), low confidant social support (22.5% and 10.9%, respectively), and with pregnancy depression (32.7% and 33.3%, respectively). Also, this incidence was higher when the partner of either sex was depressed (27.8% in mothers and 16.3% in fathers). The incidence of depression during the first 12 months post partum was higher among mothers with a history of depression and negative life events, whereas these associations were not statistically significant for fathers.

Results obtained with the two models fitted were very similar for mothers and fathers. Low marital satisfaction, partner's depression and depression during pregnancy increased the probability of depression during 12 months post partum in either sex. A history of depression was not associated with depression during 12 months post partum among mothers and fathers. Negative life events increased the risk of depression during 12 months post partum only among mothers. Lack of affective and confidant social support did not increase the risk of depression during 12 months post partum for both mothers and fathers. However, if our results were statistically significant, gender-based differences would be taken into account when determining the impact of social support on depression. If that were the case, low affective social support would be a risk factor of depression during 12 months post partum for men, whereas, for women, low confidant support would be a risk factor. The probability of postpartum depression was lower at 12 months post partum than at 3 months in mothers, although the association was at the limit of statistical significance (p=0.074). However, there was no evidence of an association between time of data collection and postpartum depression in fathers (p=0.369).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest longitudinal cohort studies of depression from the third trimester of pregnancy to 1 year after childbirth; it included both mothers and fathers attending the prenatal programme in primary care centres of the Valencian Community (Spain). This paper reports the longitudinal patterns of depression from the third trimester of pregnancy to 1 year after childbirth among mothers and fathers and presents both similarities and differences in the effect of psychosocial (marital satisfaction, social support) and personal (partner's depression, history of depression, negative life events and depression during the third trimester of pregnancy) factors on depression during the first year after childbirth, measured by the EPDS. This study has produced three main findings: (1) the incidence of depression was higher among mothers than fathers at 3 months post partum, but was similar among mothers and fathers at 12 months post partum; (2) the incidence of depression decreased during the first postpartum year for mothers, but the association is at the limit of statistical significance; (3) although most psychosocial and personal factors associated with depression 1 year after childbirth were similar for both sexes (marital satisfaction, partner's depression, pregnancy depression), negative life events were only related to women's depression. Lack of affective and confidant social support did not increase the risk of depression in either men or women.

The incidence of depression at 3 and 12 months post partum for mothers was similar to that reported by other authors who used the same cut-off score and scale of measurement.4 5 Also the incidence of fathers' depression during the first postpartum year was similar to that in the literature. Rates of depression in community-based samples of fathers during the first year after childbirth range from low (1.2%) to high (25.5%).3 Consistent with the literature,4 5 most women reported no increase in depression (78%) during the first year after childbirth. As other authors have stated, the incidence of depression at 3 months post partum was higher among mothers than fathers,6 12 27–30 but, surprisingly, the incidence was similar for mothers and fathers 1 year after childbirth. As in other recent follow-up studies, in our study there was a small decrease in the incidence of depression from 3 months to 1 year after childbirth among women,4 5 13 but the association is at the limit of statistical significance. Goodman3 pointed out that, unlike for mothers, for whom the onset of postpartum depression is usually in the early postpartum period, there is some evidence that depression among men begins later, often following the onset of depression in women, with the rate among fathers increasing over the first year. In this study, there is no evidence of a significant increase in depression 1 year after childbirth among men, which may be due to the small number of cases detected at the time of measurement (13 and 15 cases at 3 and 12 months post partum, respectively).

Similarly to other studies, a strong association was identified between poor marital relationship and depression during the first postpartum year in both sexes, and the magnitude of the OR was similar.9 10 13 14 27 31 Childbirth usually implies an additional burden of work for mothers and fathers, and consequently the relationship between partners often suffers, and it reduces leisure time as well.

In contrast with other studies,9–12 32 in this study, a lack of affective and confidant social support did not increase the risk of depression during the first 12 months post partum for either mothers or fathers. However, if our results were statistically significant, gender-based differences would be taken into account when determining the impact of social support on depression; in that case, among men low affective social support would be a risk factor for postpartum depression, and among women it would be low confidant support. With a larger sample, statistically significant differences could probably be found. Research on gender differences in styles of interpersonal relationship suggests that men are more dependent on their spouses for emotional support than on other network members. In contrast, women are more likely to seek out friends in order to share feelings and problems (confidant social support), whereas male friendships focus more on shared activities or ‘distractions’.33

It has been reported that maternal postpartum depression is a strong predictor of postpartum depression for men.3 27 30 31 34 Moreover, we have found the same association for mothers, and the magnitude of the effect was similar for both mothers and fathers.

Several studies suggest that a psychopathological history9 11 13 14 may be an important determinant of depression in women after childbirth. In this study, we used two indicators to evaluate psychopathology history (depression during pregnancy and a history of depression 12 months before pregnancy). One of these indicators (depression during pregnancy) is a strong predictor of postpartum depression among mothers and fathers.2 3 6 9 10 35 36 However, there was no evidence of association between history of depression 12 months before pregnancy and postpartum depression for either mothers or fathers. This may be explained by the fact that, when two variables are introduced to measure the same concept, the variable that plays a more important role as a predictor of depression after childbirth is the one that refers to the more recent period of exposure (depression during pregnancy).

Our results are consistent with other studies in that women who suffer negative life events9 10 13 37 were at greater risk of developing depression during the year after childbirth.

Limitations of the study

The longitudinal nature of the analysis and the adjustment for baseline depression to adjust the effect of mood on reporting psychosocial factors reduces the limitations of these data.

There were some small statistical differences in socioprofessional characteristics (age, native country, employment status, education) between respondents and non-respondents. However, mothers and fathers who did not respond for phase II and III did not have higher scores in the prevalence of depression during the third trimester of pregnancy. The prevalence of maternal depression during the third trimester of pregnancy was 9.1% versus 10.8% among respondents and non-respondents at phase II. These percentages were 9.6% and 10.7% at phase III. Among fathers these percentages were 7.0% for respondents and 5.1% for non-respondents at phase II and 7.3% and 4.8%, respectively at phase III. Therefore our results cannot be biased by selective non-response.

Implications for practice and research

Depression during pregnancy and post partum is a serious mental health problem for both mothers and fathers, and its consequences have serious implications for the welfare of the family and the psychological development of the child.10 When one parent is depressed, the child's environment is compromised, and the child is at risk of adverse outcomes (eg, behavioural problems, poor cognitive development). Moreover, risk of depression among parents increases with one partner's depression, and, when both parents are depressed, the risk for the child increases. Also, health professionals should be aware of potentially vulnerable groups (couples with marital dissatisfaction or women with negative life events) so that they can provide effective interventions (eg, intensive professionally based postpartum support, telephone peer (mother-to-mother) support).38 39

Conclusion

These findings suggest that, among longitudinal data, using time vary measures with longitudinal data, psychosocial (marital satisfaction) and personal (partner's depression, depression during the third trimester of pregnancy) factors were strong predictors of depression 1 year after childbirth for both mothers and fathers. A possible gender-specific effect of affective and confidant social support on depression 1 year after childbirth was observed. Therefore longitudinal research in an unselected population is needed to explain these possible gender differences.

What is already know on this subject.

Several studies that have assessed the evolution of the incidence of depression among mothers along the first year of life of their last born child and their risk factors.

Few researchers have included large samples of mothers and fathers with the aim of identifying gender differences in the pattern of depression during the first year after childbirth and their risk factors.

What this study adds.

With respect to longitudinal patterns of depression from the third trimester of pregnancy to 1 year after childbirth among mothers and fathers, two main findings were obtained: (1) the incidence of depression was higher among mothers than fathers at 3 months post partum, but similar at 12 months post partum among mothers and fathers; (2) the incidence of depression decreased during the first postpartum year only in mothers, but the association is at the limit of statistical significance.

A strong predictor of postnatal depression for both mothers and fathers is depression during pregnancy.

Most psychosocial and personal factors associated with depression 1 year after childbirth were similar for both sexes (marital satisfaction, partner's depression, pregnancy depression).

Footnotes

Funding: The study was partially financed by three research grants from ‘Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias’ (Ministry of Health; PI050443), Gender and Health Network (G03/42) and CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP) and two from ‘Conselleria de Sanitat. Generalitat Valenciana’ (PI-031/2004 and PI-59/2005).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Contributors: V-EA designed the study, oversaw its execution, analysed the resulting data, and wrote the article. LA assisted in interpreting findings and contributed to the analysis plan and editing of the article.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ryan D, Milis L, Misri N. Depression during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician 2005;51:1087–93 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verker GJ, Pop VJ, Van Son MJ, et al. Prediction of depression in the postpartum period: a longitudinal follow-up study in high-risk and low-risk women. J Affect Disord 2003;77:159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs 2004;45:26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heron J, O'Connor TG, Evans J, et al. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord 2004;80:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, et al. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001;323:257–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthey S, Barnett B, Ungerer J, et al. Paternal and maternal depressed mood during the transition to parenthood. J Affect Disord 2000;60:75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halbreich U, Karkum S. Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 2006;91:97–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubertsson C, Waldenström U, Wickberg B, et al. Depressive mood in early pregnancy and postpartum: prevalence and women at risk in a national Swedish sample. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2005;23:155–66 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:289–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:37–54 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen FD, Videbech P, Hedegaard M, et al. Postpartum depression: identification of women at risk. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;107:1210–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Areias M, Kumar RC, Barros H, et al. Correlates of postnatal depression in mothers and fathers. Br J Psychiatry 1996;169:36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eberhard-Grand M, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, et al. Depression during pregnancy and after delivery: a repeated measurement study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2004;25:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyce PM, Hickey AR. Psychosocial risk factors to major depression after childbirth. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:605–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia Esteve L, Ascaso Terrén C, Ojuel J, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. J Affect Disord 2003;75:71–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthey S, Barnett B, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for men, and comparison of item endorsement with their partners. J Affect Disord 2001;64:175–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowers BJ, Olson DH. ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale: a brief and clinical tool. J Fam Psychol 1993;7:176–185 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellón Saameño J, Delgado Sánchez A, de Dios Luna del Castillo J, et al. Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo social funcional Duke-UNC-11. [Validity and fiability the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire]. Aten Primaria 1996;18:153–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broadhead W, Gehlbach SH, De Gruy F, et al. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care 1988;26:709–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:221–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tammentie T, Tarkka MT, Astedt-Kurki P, et al. Sociodemographic factors of families related to postnatal depressive symptoms of mothers. Int J Nurs Pract 2002;8:240–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas JS, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, et al. Changes in the health status of women during and after pregnancy. J Gen Intern Med 2004;20:45–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolton H, Hughes P, Turton P, et al. Incidence and demographic correlates of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in an inner London population. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 1998;19:202–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escribà-Agüir V, Más Pons R, Romito P, et al. Psychological distress of new Spanish mothers. Eur J Public Health 1999;9:294–9 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Artazcoz L, Borell C, Benach J. Gender inequalities in health among workers: the relation with family demands. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:639–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domingo-Salvany A, Regidor E, Alonso J, et al. Grupo de Trabajo de la sociedad Española de Epidemiología, Grupo de Trabajo Sociedad Española de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria. Una propuesta de medida de la clase social. [Proposal for a social class measure: Working Group of the Spanish Society Epidemiology and the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine]. Aten Primaria 2000;25:350–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escribà-Agüir V, Gonzalez-Galarzo M, Barona-Vilar C, et al. Factors related to depression during pregnancy: are there gender differences? J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramchandani P, Stein A, Jonathan E, et al. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective population study. Lancet 2005;365:2201–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perren S, von Wyl A, Bürgin D, et al. Depressive symptoms and psychosocial stress across the transition to parenthood: associations with parental psychopathology and child difficulty. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2005;26:173–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballard C, Davis R, Cullen P, et al. Prevalence of postnatal psychiatric morbidity in mothers and fathers. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:782–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deater-Deckard K, Pickering K, Dunn J, et al. Family structure and depressive symptoms in men predicting and following the birth of a child. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:818–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seguin L, Potvin L, St-Denis M, et al. Depressive symptoms in the late postpartum among low socioeconomic status women. Birth 1999;26:157–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman JA, Raskin VD, Gaines C. Gender roles, social support, and postpartum depressive symptomatology. The benefits of caring. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991;179:139–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bielawska-Batorowicz E, Kassakowska-Petrycka K. Depressive mood in men after the birth of their offspring in relation to a partner's depression, social support, father's personality and prenatal expectations. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2006;24:21–9 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brockington I. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Lancet 2004;363:303–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck CT. A meta-analysis of predictors of postpartum depression. Nurse Res 1996;45:297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eberhard-Grand M, Eskild A, Tambs K, et al. Depression in postpartum and non-postpartum women: prevalence and risk factors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;106:426–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dennis CL. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal depression: systematic review. BMJ 2005;331:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dennis CL, Kenton L, Weston J, et al. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:a3064 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]