Abstract

The molecular basis for the preferential metastases of certain cancers to bone is not well understood. In this issue of the JCI, Shiozawa et al. provide compelling evidence that prostate cancer cells preferentially home to the osteoblastic niche in the bone marrow, where they compete with normal HSCs for niche support. Because signals from the niche may regulate tumor quiescence and sensitivity to chemotherapy, these observations have important implications for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer in bone.

Bone is a common site of metastases for certain tumors, including breast cancer and prostate cancer (PCa). Approximately 70% of patients with PCa have bone metastases at the time of death (1). The molecular basis for this preferential growth in the bone marrow and the biological effects of the rich microenvironment in the bone marrow on cancer cell growth and survival are not well understood. In this issue, Shiozawa et al. provide compelling evidence that PCa cells preferentially home to the osteoblastic niche in the bone marrow, where they compete with normal HSCs for niche support (2). Because signals from the niche may regulate the quiescence and survival of PCa cells (and possibly sensitivity to chemotherapy), these observations have important implications for the treatment of metastatic bone cancer.

The bone marrow microenvironment plays a critical role in the maintenance of HSC quiescence and self-renewal. HSCs preferentially localize in the bone marrow, either to a perivascular location or near the endosteum (3, 4). Although the stem cell niche in the bone marrow is likely to be complex, with contributions from endothelial cells, advential reticular cells, nestin-positive stromal cells (5), and CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells (6, 7), current evidence suggests that osteoblast lineage cells are a key component of the endosteal niche and are required to maintain normal HSC function. Expansion of osteoblast lineage cells by genetic or pharmacologic means results in concurrent expansion of HSCs (8). Conversely, ablation of osteoblasts using a suicide gene results in a loss of HSCs (9).

CXCL12/CXCR4 axis

Although the signals generated by the stem cell niche that regulate HSCs are not fully understood, a key player is CXCL12 (also known as stromal-derived factor–1), a chemokine constitutively expressed at high levels in the bone marrow by osteoblasts, endothelial cells, and other bone marrow stromal cells. CXCL12, primarily through interaction with its major receptor, CXCR4, regulates HSC quiescence and homing to the bone marrow (10, 11). Disruption of CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling is a key step in cytokine-induced HSC mobilization from bone marrow to blood (12). The importance of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is shown by the success of the CXCR4 inhibitor plerixafor (AMD3100; Genzyme) to rapidly mobilize HSCs in humans (13). Other agents produced by stromal cells in the endosteal niche that have been implicated in the regulation of HSCs include angiopoietin-1, thrombopoietin, and mediators of Notch and Wnt signaling (14–16).

Certain tumors, including PCa cells, appear to have coopted the CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling pathway to preferentially home to the bone marrow. Whereas CXCR4 expression is low or absent in many normal tissues, it is expressed at high levels in more than 23 different cancers, including breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and PCa (17).

Importantly, inhibition of CXCR4 signaling has been shown to reduce metastatic disease of multiple tumor types in mouse xenograft models. The growth and metastasis of PCa cells injected into nude mice, for example, was inhibited by a neutralizing antibody to CXCR4 (15). Similarly, treatment of mice with small-molecule inhibitors of CXCR4 reduced the metastatic burden of transplanted breast cancer cells (18, 19).

Sharing a niche

Although tumor cells and HSCs use similar homing mechanisms, it has not been clear whether tumor cells directly occupy the HSC niche. Shiozawa et al. now provide compelling evidence that prostate tumor cells directly compete with HSCs for residence in the endosteal niche (2). Using a PCa xenograft model, they showed reduced HSC number and function in mice with micrometastases. Moreover, coinjection of PCa cells (but not control nonmetastatic transformed prostate epithelial cells) with normal murine or human HSCs decreased their engraftment in the bone marrow. Importantly, multiphoton imaging demonstrated that transplanted HSCs and PCa cells localized to the same (endosteal) region of the bone marrow. Perhaps most convincingly, they show that manipulation of the osteoblast niche affected the development of metastases: treatment with parathyroid hormone, which expands osteoblasts, increased the metastatic burden, whereas ablation of osteoblasts was associated with a reduced number of metastases.

There are several important clinical implications of these findings. First, displacement of normal HSCs from the niche by cancer cells may contribute to the peripheral cytopenias (e.g., neutropenia and anemia) that are common in patients with metastatic cancer. Second, because signals from the endosteal niche contribute to HSC quiescence and survival, it is possible that cancer cells located in the niche may acquire a more quiescent and stem-like phenotype, perhaps facilitating dormancy. Consistent with this possibility, disseminated tumor cells are commonly found in the bone marrow of men with PCa at the time of prostatectomy, and persistence of these cells after surgery is associated with an increased risk of recurrence (20). Third, the study by Shiozawa et al. predicts that agents that mobilize HSCs from the niche may also mobilize cancer cells; indeed, treatment of mice with the small-molecule CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 or G-CSF, both potent mobilizing agents for HSCs, led to egress of PCa cells from the bone marrow (2).

Evolving strategies

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this work is that it suggests potential strategies to disrupt cancer/stromal cell interactions in the bone marrow to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy (Figure 1). Although direct experimental evidence is lacking, signals from the osteoblast niche are predicted to induce cancer cell quiescence and provide survival signals, rendering cells resistant to chemotherapy. It follows that mobilization of cancer cells out of the niche using AMD3100, G-CSF, or other mobilizing agents may render the cells more sensitive to chemotherapy. In fact, there is evidence that treatment with AMD3100 sensitizes acute myeloid leukemia cells to chemotherapy (21), and phase I/II clinical trials of CXCR4 inhibitors (CTCE-9908, British Canadian BioSciences Corp.; MSX-122,Metastatix Inc.) have been initiated for patients with refractory metastatic solid tumors. Caution is advised in using CXCR4 antagonists, however, as long-term disruption of the HSC niche could have clinically relevant effects on hematopoiesis and could potentially increase metastases to other anatomic sites.

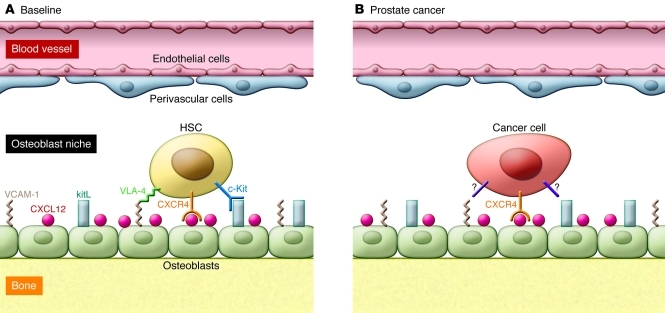

Figure 1. Tumor cells compete for the HSC niche.

(A) HSCs reside in perivascular and endosteal niches within the bone marrow. Osteoblast lineage cells produce factors, including CXCL12, VCAM-1, and c-Kit ligand (kitL; also known as stem cell factor), that retain HSCs in the marrow and help maintain their quiescence and self-renewal capacities. (B) PCa cells, by coopting the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, compete with normal HSCs for residence in the niche. Signals from the niche that promote the quiescence and self-renewal of HSCs may likewise maintain tumor cells in a more stem-like state, facilitating marrow metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy.

Several important questions are raised by this study. Experiments were performed in immunodeficient mice using a PCa cell line. Do primary PCa cells also engraft the osteoblast niche in human bone marrow? Do other cancers with a predilection for metastases to bone also home to the osteoblast niche? Finally, studies are needed to better characterize the biological effects of the osteoblast niche on the survival, quiescence, and sensitivity to chemotherapy of cancer cells. Ultimately, identification of the niche signals that regulate cancer cell phenotype may provide targeted strategies to render metastatic bone cancers more susceptible to chemotherapy.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1253–1255. doi:10.1172/JCI57229.

See the related article beginning on page 1298.

References

- 1.Roodman GD. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. . N Engl J Med. 2004;350(16):1655–1664. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiozawa Y, et al. Human prostate cancer metastases target the hematopoietic stem cell niche to establish footholds in mouse bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1298–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI43414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121(7):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, Coverdale JA. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood. 2001;97(8):2293–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.8.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendez-Ferrer S, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466(7308):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25(6):977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omatsu Y, et al. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33(3):387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visnjic D, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Katavic V, Lorenzo J, Aguila HL. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. 2004;103(9):3258–3264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cashman J, Clark-Lewis I, Eaves A, Eaves C. Stromal-derived factor 1 inhibits the cycling of very primitive human hematopoietic cells in vitro and in NOD/SCID mice. Blood. 2002;99(3):792–799. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.3.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peled A, et al. Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science. 1999;283(5403):845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christopher MJ, Liu F, Hilton MJ, Long F, Link DC. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009;114(7):1331–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liles WC, et al. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102(8):2728–2730. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai F, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshihara H, et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(6):685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan AW, et al. Integration of Notch and Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(3):314–322. doi: 10.1038/ni1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balkwill F. The significance of cancer cell expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Z, et al. Inhibition of breast cancer metastasis by selective synthetic polypeptide against CXCR4. Cancer Res. 2004;64(12):4302–4308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang EH, et al. A CXCR4 antagonist CTCE-9908 inhibits primary tumor growth and metastasis of breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2009;155(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan TM, et al. Disseminated tumor cells in prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy and without evidence of disease predicts biochemical recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(2):677–683. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nervi B, et al. Chemosensitization of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) following mobilization by the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100. Blood. 2009;113(24):6206–6214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]