Abstract

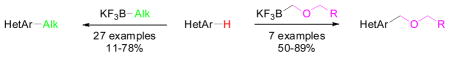

A direct alkylation of various heteroaryls using stoichiometric potassium alkyl and alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates has been developed. This method leads to the synthesis of complex substituted heterocycles, which have been obtained with yields up to 89%.

Heteroaryl moieties are important components in natural products and pharmaceutical drugs.1 In the past decade, many publications have reported C-H bond activations of heterocycles using base/copper salts with subsequent coupling to aryl halides,2 and direct C-H activation/arylation of heteroaromatics through palladium activation of aryl and heteroaryl halides has also been observed.3 Few examples of carbon-carbon bond formation involving organoboron compounds have been reported. In these contributions, C-H bond activation of heteroarenes can be performed with arylboronic acids in the presence of a catalytic amount of palladium acetate and either stoichiometric copper acetate or TEMPO.4 These transformations were postulated to proceed via organopalladium intermediates generated by transmetalation from the boronic acids.

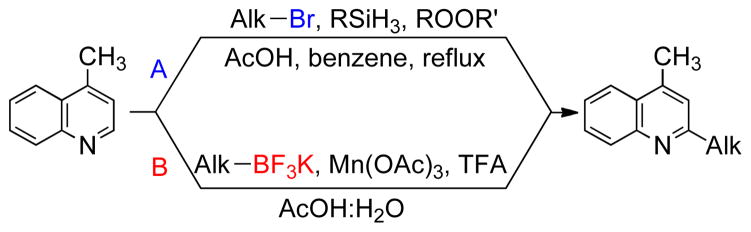

The Minisci reaction and related processes provide another useful means to alkylate or arylate various heteroarenes via C-H bond substitution5 in which radical intermediates add to activated aromatic systems (Scheme 1).6 Within this context, the reactivity of a variety of radical precursors has been studied with quinolines7 and derivatives such as lepidine,8 but the conditions often involve the use of the heteroaryl substrate as a solvent.

Scheme 1. Overview.

Route A: Minisci reaction using alkyl halides, Route B: direct alkylation with potassium alkyltrifluoroborates.

Interestingly, there is a relatively recent recognition that arylborons can serve as radical precursors in C-C bond-forming reactions via oxidative carbon-boron bond cleavage.9 Among the different metal oxidants that can be employed for this reaction, manganese acetate has proven to be efficient for the C-H arylation of olefins,10 arenes, and heteroarenes using arylboronic acids.11 However, the latter cases either used the substrate as a solvent or the reaction was performed with a 10-fold excess of the arene/heteroarene at 170 °C under microwave conditions. During the course of our investigations, Baran and coworkers reported a method for direct arylation of heterocycles using a 50% excess of arylboronic acids, employing potassium persulfate and catalytic silver nitrate as oxidants.12

Because of their lack of an empty p-orbital, potassium organotrifluoroborates are more stable toward numerous reagents than their corresponding boronic acids. This important characteristic facilitates their ease of handling, storability, and robustness under harsh reaction conditions. Over the last decade, these compounds have proven to be excellent partners in Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling and other transition metal catalyzed reactions.13 As is the case with boronic acids, there has been a recognition that the trifluoroborates can also serve as radical precursors. Indeed, Fensterbank et al. recently reported that potassium alkyltrifluoroborates serve as precursors to radicals in a variety of reactions under oxidative conditions employing copper acetate or copper chloride and TEMPO.14

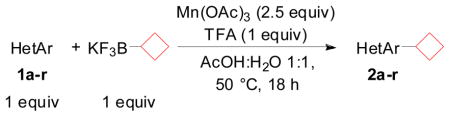

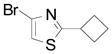

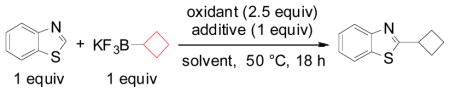

Herein, we reveal our initial investigations on the use of stoichiometric organotrifluoroborates as radical precursors in the first direct C-H alkylation of heteroaryls with potassium alkyl- and alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates. We chose to optimize this reaction by testing the direct alkylation of benzothiazole with potassium cyclobutyltrifluoroborate. First, different metal and non-metal oxidants were tried (entries 1–8). Next, different additives (entries 9–13) and various solvents (entries 14–19) were tested, and from these studies it appeared that the highest conversion was obtained with manganese(III) acetate in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid in a 1:1 mixture of acetic acid: water (entry 10).

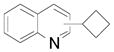

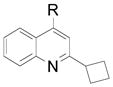

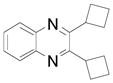

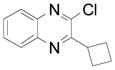

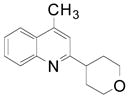

Using these conditions a variety of heteroaryl substrates have been engaged in reactions with potassium cyclobutyltrifluoroborate (Table 2). Reactions with quinoline and derivatives 1a–k afford yields up to 65% (entries 1–8).

Table 2.

Scope of Coupling with Diverse Heteroaryls

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | heteroaryl | yield (%)a | |

| 1 |  |

2aa, 2ab C2:C4 (70:30) | 44 (58) |

| 2 |  |

2b R= Me 2c R= Cl |

65 (83) 56 (81) |

| 3 |  |

2da 2db |

54% + 17% (92) |

| 4 |  |

2e R= 3-CO2Me 2f R= 4-Br 2g R= 5-Br |

59 (75) 61 (80) 64 (82) |

| 5 |  |

2h | 59 (72) |

| 6 |  |

2i | 59 (81)b |

| 7 |  |

2j | 61 (70) |

| 8 |  |

2k | 34 (77) |

| 9 |  |

2l R: H 2m R: Me |

60 (63) 60 (70) |

| 10 | 2n | 54 (76) | |

| 11 |  |

2o R= H 2p R= Br 2q R= Ph |

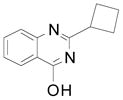

31 (93) 42 (54) 34 (66) |

| 12 |  |

2r | 11 (74) |

Heterocycle (1.0 mmol), potassium cyclobutyltrifluoroborate (1.0 mmol), Mn(OAc)3 (2.5 mmol), TFA (1.0 mmol), AcOH/H2O 1:1 (0.08 M), 50 °C, 18 h.

Isolated yields and conversions (indicated in parentheses) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude mixture.

Heterocycle (1.0 mmol), potassium cyclobutyltrifluoroborate (3.5 mmol), Mn(OAc)3 (5.0 mmol), TFA (1.0 mmol), AcOH/H2O 1:1 (0.08 M), 50 °C, 18 h.

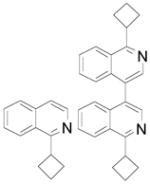

As reported in the literature,15 quinoline 1a presents two electron-deficient positions, so both regioisomers were isolated in 44% combined yield, and 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixture indicated the presence of a 70:30 ratio of 2aa/2ab. Isoquinoline 1d gives the expected heteroaryl 2d, but also the corresponding dimer.

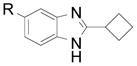

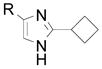

This side product is obtained by reaction between two radical intermediate species.16 Azole compounds 1l–r also gave good conversions (entries 9–12), but the yields are low because of the difficulty in separating compounds 2o–r from the corresponding starting material (entries 11–12).

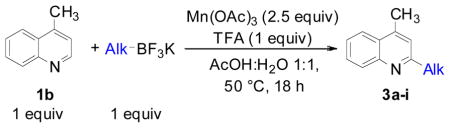

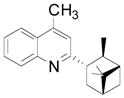

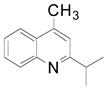

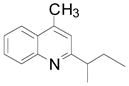

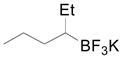

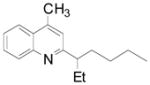

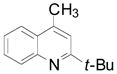

We next evaluated the reactivity of lepidine toward different primary, secondary and tertiary potassium alkyltrifluoroborates (Table 3). The alkylated heteroaryls 3a–i were obtained with yields between 25 and 78%.

Table 3.

Scope of the Alkyltrifluoroborates.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | potassium alkyl trifluoroborate | product | yield (%)a |

| 1 |

3a 3a

|

75 (83) | |

| 2 |

3b 3b

|

75 (79) | |

| 3 |

3c 3c

|

40 (57) | |

| 4 |  |

3d 3d

|

48 (52) |

| 5 |

3e 3e

|

25 (45) | |

| 6 |

3f 3f

|

69 (85) | |

| 7 |

3g 3g

|

78 (83) | |

| 8 |  |

3h 3h

|

68 (70) |

| 9 | t-Bu BF3K |

3i 3i

|

50 (58) |

Lepidine (1.0 mmol), potassium alkoxymethyltrifluoroborate (1.0 mmol), Mn(OAc)3 (2.5 mmol), TFA (1.0 mmol), AcOH/H2O 1:1 (0.08 M), 50 °C, 18 h.

Isolated yields and conversions (indicated in

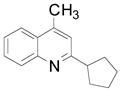

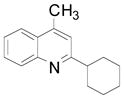

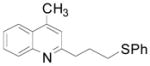

Cyclopentyl and cyclohexyl substituents were successfully added from the corresponding potassium cycloalkyltrifluoroborates with 75% yields for both (entries 1, 2), but the tetrahydropyranyl derivative gave a lower yield (entry 3). The hindered potassium isopinocampheyltrifluoroborate was also coupled to give substituted lepidine 3d with complete stereoselectivity (entry 4). The ease of alkyltrifluoroborate oxidation and the nucleophilic character of the in situ formed alkyl radicals could both provide the driving force for the reaction, as the reactivity appears to increase on going from primary to secondary and tertiary radicals.17 This could explain the low yield obtained for compound 3e. Good yields are observed for heteroaryls 3f–i, which are substituted by linear secondary and tertiary alkyls, respectively (entries 6–9).

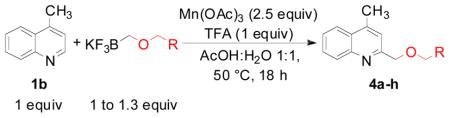

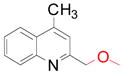

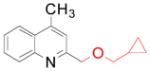

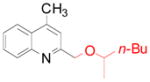

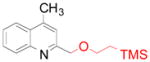

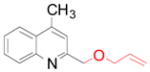

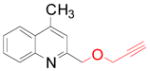

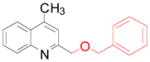

For the third part of our investigation, it was of interest to test the reactivity of various potassium alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates toward lepidine, because ethers induce a change of solubility that is important in drug administration.18 Diverse potassium alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates were sucessfully coupled to lepidine (Table 4) with yields between 58 and 89%. Some of these organoborons were made by a process that started with bromomethyltrifluoroborate and may have contained some bromide salts.19 To counter that possibility, in these cases the trifluoroborates were used in excess (entries 4, 6). The alkoxymethylation reaction is tolerant of a range of functional groups present on the boron reagent, including alkene, alkyne and benzyl groups (entries 5, 6 and 7).

Table 4.

Scope of Alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yield (%)c |

| 1 |

4a 4a

|

50 (70)a |

| 2 |

4b 4b

|

68 (72)a |

| 3 |

4c 4c

|

58 (76)a |

| 4 |

4d 4d

|

89 (100)b |

| 5 |

4e 4e

|

65 (76)a |

| 6 |

4f 4f

|

65 (74)b |

| 7 |

4g 4g

|

67 (83)a |

Lepidine (1.0 mmol), potassium alkoxymethyltrifluoroborate (1.0 mmol), Mn(OAc)3 (2.5 mmol), TFA (1.0 mmol), AcOH/H2O 1:1 (0.08 M), 50 °C, 18 h.

1.3 mmol of potassium alkoxymethyltrifluoroborate.

Isolated yields and conversions (indicated in parentheses) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude mixture.

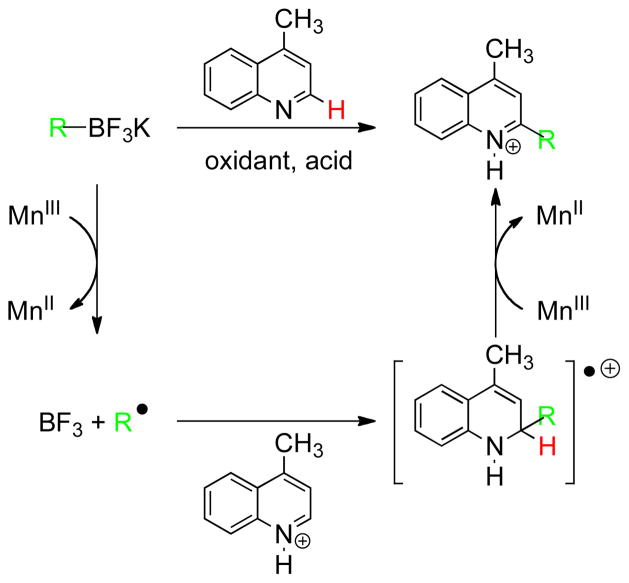

In accord with precedents established in previous studies,7b,8b,12,14 a possible mechanism can be proposed (Scheme 2). The first step involves a homolytic cleavage of the C-B bond using one equivalent of manganese(III) acetate. Subsequently, the alkyl radical adds to the protonated heteroaryl to form the corresponding radical cation intermediate, which leads to the protonated heteroaromatic after a second oxidation. Basic workup leads to the final observed product.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism with lepidine.

In summary, we have reported the first direct alkylation of various heterocyles using potassium alkyl- and alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates as nucleophilic radical precursors. Moderate to good yields are achieved, in most cases using a stoichiometric amount of both reacting partners. This method fills an important void in that Friedel-Crafts alkylations fail for nearly all heterocyclic systems, and it also represents an efficient way to decorate heteroaryl subunits with unique alkyl substituents (e.g., cyclobutyl and alkoxymethyl groups). Current research efforts seek to expand the process to other distinctive substrates and substituents.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Optimization of C-H Alkylation

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | oxidant | additive | solvent | GCMS conversion |

| 1 | Mn(OAc)3 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 71% |

| 2 | Cu(OAc)2 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 1% |

| 3 | KMnO4 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 20% |

| 4 | Ce(SO4)2 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 54% |

| 5 | K2Cr2O7 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 26% |

| 6 | Fe(SO4)2•7H2O | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 6% |

| 7 | (NH4) 2S2O7 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 12% |

| 8 | benzoquinone | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 3% |

| 9 | Mn(OAc)3 | H2SO4 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 6% |

| 10 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 78% (60%)a |

| 11 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFAb | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 71% |

| 12 | Mn(OAc)3 | KHF2 | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 71% |

| 13 | Mn(OAc)3 | - | AcOH:H2O 1:1 | 65% |

| 14 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | AcOH | 48% |

| 15 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | DMSO | 4% |

| 16 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | CH3CN | 41% |

| 17 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | MeOH | 54% |

| 18 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | ClCH2CH2Cl | 51% |

| 19 | Mn(OAc)3 | TFA | acetone | 31% |

Reaction performed at room temperature.

Reaction performed with only 0.2 equiv of trifluoroacetic acid.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frontier Scientific and Aldrich for a donation of boronic acids. Financial support has been provided by the NIH General Medical Sciences (R01 GM035249). Dr. Floriane Beaumard and Luciana Felix (University of Pennsylvania) are acknowledged for making potassium alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates and cyclobutyltrifluoroborate, respectively. Dr. Rakesh Kohli (University of Pennsylvania) is acknowledged for obtaining HRMS data.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For bioactive quinoline derivatives, see: Kolasa T, Gunn DE, Bhatia P, Woolds KW, Gane T, Stewart AO, Bouska JB, Harris RR, Hulkower KI, Malo PE, Bell RL, Carter GW, Brooks CDW. J Med Chem. 2000;43:690–705. doi: 10.1021/jm9904102.Narayanan S, Vangapandu S, Jain R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1133–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00154-8.Jain R, Vaitilingam B, Nayyar A, Palde PB. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00074-x.Payne JE, Bonnefous C, Symons KT, Nguyen PM, Sablad M, Rozenkrants N, Zhang Y, Wang L, Yazdani N, Shiau AK, Noble SA, Rix P, Rao TS, Hassig CA, Smith ND. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7739–7755. doi: 10.1021/jm100828n.For active alkylated benzimidazoles, see: Bali A, Bansal Y, Sugumaran M, Singh Saggu J, Balakumar P, Kaur G, Bansal G, Sharma A, Singh M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;15:3962–3965. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.05.054.Capkauskaite E, Baranauskiene L, Golovenko D, Manakova E, Grazulis S, Tumkevicius S, Matulis D. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:7357–7364. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.016.Kumar S, Bawa S, Gupta H. Mini-Rev in Med Chem. 2009;9:1648–1654. doi: 10.2174/138955709791012247.

- 2.(a) Do HQ, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12404–12405. doi: 10.1021/ja075802+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Do H-Q, Kashif Khan RM, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15185–15192. doi: 10.1021/ja805688p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yoshizumi T, Tsurugi H, Satoh T, Miura M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:1598–1600. [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhao D, Wang W, Lian S, Yang F, Lan J, You J. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:1337–1340. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Barbero N, SanMatin R, Dominguez E. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:841–845. doi: 10.1039/b916549e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem Rev. 2007;107:174–238. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Beck EM, Gaunt MJ. Top Curr Chem. 2009;292:85–121. doi: 10.1007/128_2009_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fall Y, Reynaud C, Doucet H, Santelli M. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:4041–4050. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Liu B, Qin X, Li K, Li X, Guo Q, Lan J, You J. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:11836–11839. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kirchberg S, Tani S, Ueda K, Yamagushi J, Studer A, Itami K. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011 doi: 10.1002/anie.201007060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Minisci F, Vismara E, Fontana F. Heterocycles. 1989;28:489–519. [Google Scholar]; (b) Harrowven DC, Sutton BJ. Prog Heterocyclic Chem. 2004;16:27–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Minisci F, Galli R, Cecere M, Malatesta V, Caronna T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968:5609–5612. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bowman WR, Storey JMD. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1803–1822. doi: 10.1039/b605183a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vaillard SE, Schulte B, Studer A. In: Modern Arylation Methods. Ackermann L, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2009. pp. 475–511. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Minisci F, Vismara E, Fontana F, Morini G, Serravalle M. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4411–4416. [Google Scholar]; (b) Minisci F, Vismara E, Fontana F. J Org Chem. 1989;54:5224–5227. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Minisci F, Giordano C, Vismara E, Levi S, Tortelli V. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:7146–7150. [Google Scholar]; (b) Minisci F, Fontana F, Pianese G, Ming Yan Y. J Org Chem. 1993;58:4207–4211. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ollivier C, Renaud P. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3415–3434. doi: 10.1021/cr010001p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Darmency V, Renaud P. Top Curr Chem. 2006;263:71–106. [Google Scholar]; (c) Vogler T, Studer A. Org Lett. 2008;10:129–131. doi: 10.1021/ol702659a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pouliot M, Renaud P, Schenk K, Studer A, Vogler T. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:6037–6040. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickschat A, Studer A. Org Lett. 2010;12:578–580. doi: 10.1021/ol101818k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Demir AS, Reis O, Emrullahoglu M. J Org Chem. 2003;68:578–580. doi: 10.1021/jo026466c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guchhait SK, Kashyap M, Saraf S. Synthesis. 2010;7:1166–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seiple IB, Su S, Rodriguez RA, Gianatassio R, Fujiwara Y, Sobel AL, Baran P. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13194–13196. doi: 10.1021/ja1066459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Stefani HA, Cella R, Vieira AS. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3623–3658. [Google Scholar]; (b) Molander GA, Ellis N. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:275–286. doi: 10.1021/ar050199q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Darses S, Genêt JP. Chem Rev. 2008;108:288–325. doi: 10.1021/cr0509758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorin G, Malloquin RM, Contie Y, Baralle A, Malacria M, Goddard JP, Fensterbank L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:8721–8723. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gebauer M, Heinisch G, Lötsch Tetrahedron. 1988;44:2449–2455. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minisci F, Galli R, Malatesta V, Caronna T. Tetrahedron. 1970;26:4083–4091.parentheses) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude mixture.

- 17.Minisci F, Mondelli R, Gardini GP, Porta O. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:2403. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Nudelman A, Elisheva G, Katz Y, Azulai R, Cohen-Ohana M, Zhuk R, Sampson SR, Langzam L, Fibach E, Prus E, Pugach V, Raphaeli A. Eur J Med Chem. 2001;36:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)01199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shirasaki Y, Miyashita H, Yamagushi M, Inoue J, Nakamura M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:4473–4484. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartz RA, Ahuja VT, Mattson RJ, Denhart DJ, Deskus JA, Vrudhula VM, Pan S, Ditta JL, Shu Y-Z, Grace JE, Lentz KA, Lelas S, Li Y-W, Molski TF, Krishnananthan S, Wong H, Qian-Cutrone J, Schartman R, Denton R, Lodge NJ, Zaczek R, Macor JE, Bronson JJ. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7653–7668. doi: 10.1021/jm900716v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raushel J, Sandrock DL, Josyula KV, Pakyz D, Molander GA. manuscript submitted. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.