Abstract

Tenascin C (TNC) is an extracellular matrix glycoprotein up-regulated in solid tumors. Higher TNC expression is shown in invading fronts of breast cancer, which correlates with poorer patient outcome. We examined whether TNC induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer. Immunohistochemical analysis of invasive ductal carcinomas showed that TNC deposition was frequent in stroma with scattered cancer cells in peripheral margins of tumors. The addition of TNC to the medium of the MCF-7 breast cancer cells caused EMT-like change and delocalization of E-cadherin and β-catenin from cell-cell contact. Although amounts of E-cadherin and β-catenin were not changed after EMT in total lysates, they were increased in the Triton X-100-soluble fractions, indicating movement from the membrane into the cytosol. In wound healing assay, cells were scattered from wound edges and showed faster migration after TNC treatment. The EMT phenotype was correlated with SRC activation through phosphorylation at Y418 and phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) at Y861 and Y925 of SRC substrate sites. These phosphorylated proteins colocalized with αv integrin-positive adhesion plaques. A neutralizing antibody against αv or a SRC kinase inhibitor blocked EMT. TNC could induce EMT-like change showing loss of intercellular adhesion and enhanced migration in breast cancer cells, associated with FAK phosphorylation by SRC; this may be responsible for the observed promotion of TNC in breast cancer invasion.

Epithelial cells are polarized and tightly interconnected by cellular junctions, whereas mesenchymal cells never form stable intercellular contacts in adult tissues. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a process whereby polarized epithelial cells are converted into mesenchymal cells during embryogenesis and in diseased tissues.1–4 EMT events also take place during tumor progression in association with invasion and metastasis, when carcinoma cells stably or transiently lose their epithelial polarity and intercellular connections, allowing them to escape the surrounding epithelium and acquire higher locomotive behavior like mesenchymal cells.2,5–8 Many recent studies have demonstrated that EMT is controlled by complex signaling pathways initiated from tyrosine-receptor kinases, transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) receptors, Wnt pathways, Notch pathways, and integrins, which are triggered by various extracellular signals.2,4,9 The activated pathways, including RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphoinositol 3 kinase, SRC, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK), also induce cytoskeletal reorganization, causing dissociation of E-cadherin from the membrane, loss of epithelial morphology, and increased cell motility.2,4,9,10 Expression of transcriptional regulators such as SNAI1/2 and TWIST, followed by transcriptional switching from epithelial markers to mesenchymal ones, also has been reported.2,11,12

Tenascin C (TNC) is a large hexameric extracellular matrix glycoprotein that exhibits de-adhesive effects on cell-matrix interaction, enhancing cell proliferation and motility in most cell types.13 TNC is highly expressed in remodeling tissues during embryonic development and under pathological conditions in adults. In development, its expression is known to be associated with classic EMT events including gastrulation14 and formation of the neural crest,15 endocardial cushion,16,17 and secondary palate.18 In normal mammary gland, TNC expression is limited, but elevation occurs in breast cancer tissues with production by both tumor and stromal cells.19,20 Immunohistochemical studies of invasive ductal carcinoma cases have demonstrated that expression is indicative of a poorer patient outcome.21 It has been reported that TNC promotes proliferation and migratory activity of cancer cells22–25 and up-regulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases by breast cancer cells.24,26 Furthermore, it is important to note that TNC expression is frequently observed in invasion borders of cancer tissues and in microinvasive foci around intraductal carcinomas, where cells may undergo EMT.23,27–29 TNC immunostaining in invasive fronts is correlated with higher risk of distant metastasis and local recurrence.27,28 In mammary epithelial cell differentiation, TNC expression is inversely correlated with the polarized epithelial phenotype and the addition of TNC disturbs dome formation in vitro, indicating TNC interference with induction and maintenance of cytodifferentiation.30 These observations support the hypothesis that TNC is an extracellular trigger of EMT in breast cancer progression, although there is still no direct evidence to confirm this.

Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the expression of TNC in different morphological types of breast cancer, solid and scattered, by immunohistochemistry. In in vitro studies using MCF-7 cells—a breast cancer cell line that shows a typical epithelial character with tight intercellular contacts and does not produce TNC under typical culture conditions24,31—we examined the effects of exogenous TNC on morphology and internalization of E-cadherin/β-catenin. The molecular mechanisms that underlie EMT induced by TNC were explored also.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 35 cases of invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast using archival samples that had been fixed in formalin and routinely processed for embedding in paraffin. Use of the samples was approved by written informed consent from the patients under a protocol authorized by the ethical committee of Mie University School of Medicine. All sections were cut at a thickness of 4 μm, placed on silane-coated glass slides, and incubated in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 15 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigen retrieval was performed using an autoclave (121°C for 1 minute). Sections were then treated with Super Block solution (Scytek Laboratories, Logan, UT) before incubation with anti-TNC antibody (4F10TT,23 1 μg/ml; IBL Japan, Takasaki, Japan) overnight at 4°C. After being washed, they were treated with a commercially available LSAB kit (Scytek), followed by color development with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine 4HCl (DAB)/H2O2 solution. Light counterstaining with hematoxylin was performed to aid orientation.

The invasive patterns of ductal carcinomas at the peripheral margins of the tumors were classified into two groups: solid and scattered. A maximum of three representative areas of each type were selected in each breast cancer specimen, and TNC immunoreactivity was assessed in 63 solid- and 84 scattered-type areas. TNC labeling around or between cancer nests in the peripheral margins was defined as positive.

Cell Culture and EMT Induction

MCF-7 cells were obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank of the Japan Health Sciences Foundation (Tokyo, Japan) and routinely cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% nonessential amino acid solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were trypsinized, collected by brief centrifugation, and resuspended in DMEM with 5% FBS. They were seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well (1 ml) in 12-well plates (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ), then 10 μg/ml TNC was added. The TNC had been purified from conditioned medium of human glioma cell line U251MG as previously described.22 After 16 hours of incubation, 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was added and the cells were cultured for another 48 hours. Neutralizing antibodies for the αv integrin subunit (AV1, 1:40; Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) or β1 (P4C10, 5 μg/ml; Millipore) and the SRC kinase inhibitor (pp2, 10 μmol/L, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) were added to the medium when the cells were plated. A neutralizing antibody for TGF-β (50 μg/ml, 1D11; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used also. As a negative control, TNC solution (10 μg) was reacted with 13 μg of rabbit polyclonal affinity-purified TNC antibody23 for 6 hours, followed by precipitation with protein A beads (10 μL) for 16 hours, and the supernatant was added to the medium.

Another breast cancer cell line, T-47D, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and grown in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS and 0.2 U/ml bovine insulin. This cell line also shows an epithelial phenotype and does not synthesize TNC.24,31 To examine EMT change, the bottom surfaces of the wells were incubated with 80 μL of 250 μg/ml TNC solution for 1 hour, then the cell suspension in DMEM/5% FBS medium was poured into the wells. TGF-β1 was added after 16 hours of incubation.

Immunofluorescence

MCF-7 or T-47D cells were grown on circular cover glasses (18-mm diameter) in 12-well plates, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 minutes and then permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). After treatment with 10% normal goat serum, they were exposed to primary antibodies (200-fold diluted) specific for E-cadherin (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), β-catenin (BD Bioscience), phosphorylated sites of FAK [pY397 (Biosource, Camarillo, CA), pY861 (Biosource), pY925 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA)], and a phosphorylated form of SRC at Y418 (Y416 for chicken; Cell Signaling Technology). Subsequently, the cells were treated with appropriate secondary antibodies, fluorescein-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (200-fold diluted; MBL, Nagoya, Japan). For double immunofluorescence, rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (200-fold diluted; Tago, Burlingame, CA) was used instead of the fluorescein-labeled antibody. Observation was performed under an epifluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets and a 40× or 60× objective lens (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and photographs were taken using a cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Immunoblot Analysis

To examine expression levels of cell adhesion molecules, FAK, and SRC, cells cultured on 6-well plates (1.4 × 105 cells/well) underwent lysis under denaturing conditions using a warmed buffer [1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer, pH 6.8, with 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate]. The amount of protein in each extract was evaluated using the BCA (bicinchoninic acid) assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of total protein were mixed with Laemmli's sample buffer and underwent electrophoresis on 5% to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gels. The proteins were electrically transferred to PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes, and immunoblotting was performed with antibodies specific for E-cadherin, β-catenin, and α-tubulin (Cederlane, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) as an intrinsic control, followed by peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG (3000–5000×; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) or anti-rabbit IgG (3000×; Sigma-Aldrich) and ECL or ECL Plus detection (GE Healthcare). First antibodies were usually used at 2000- to 3000-fold dilution. Intensities of the bands were quantified using Image J software and the values were normalized to intensities of α-tubulin bands. Total FAK and phosphorylated FAK were detected using antibodies against FAK (Cell Signaling Technology) and the phosphorylated sites, Y397 (Cell Signaling Technology), Y861 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and Y925. Total SRC (Cell Signaling Technology) and the phosphorylation at Y418 also were examined. The values were normalized to intensities of total FAK or SRC bands. Antibodies against N-cadherin (3B9; Zymed Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA), vimentin (Vim 13.2; Sigma-Aldrich), and TNC (0.1 μg/ml) also were used.

Triton X-100 fractionation was further conducted to examine intracellular localization of E-cadherin and β-catenin. The cells were extracted at 37°C with 200 μL of 0.5% Triton X-100, 2.5 mmol/L EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid), 5 mmol/L MgCl2 (magnesium chloride), and 50 mmol/L PIPES (1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid), pH 6.2, for 2 minutes.32,33 The Triton X-100-soluble fraction was collected and the plates were washed twice with the same buffer. The insoluble fraction was extracted with 200 μL of the buffer with 1% SDS.

All quantitative experiments were performed at least in triplicate.

Wound Healing Assay

Migration activity was determined using wound healing assay.22 The wells of 12-well plates were incubated with 20 μg of TNC per well for 1 hour. The suspension of MCF-7 cells (1 × 106 cells/well) was poured into a well and grown until subconfluence and further incubated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 hours. The confluent cell layer was scratched with a pipette chip, followed by medium change. Photographs (4 fields/well) were taken and TNC and/or TGF-β1 were added at the same concentration. After 24 hours, cells were fixed and stained with 0.1% crystal violet/20% ethanol/1% formaldehyde. The fields previously recorded were photographed, and the areas newly covered by the migrating cells were measured using Image J software. Ten wells per condition were examined.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in TNC staining with reference to histological patterns were assessed by Fisher's exact test. With quantitative data, group means were compared using one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni means comparison test. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

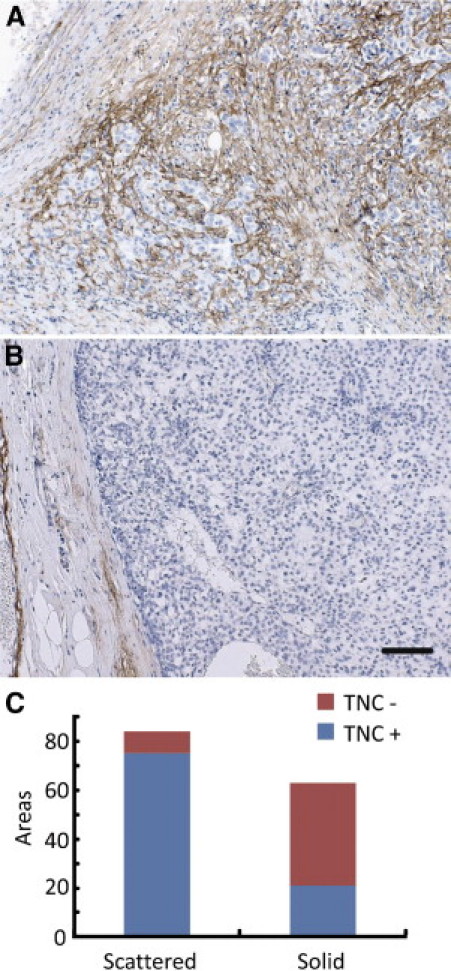

TNC-Positive Stroma Is Frequently Observed in Areas Showing Scattered Type of Invasion in Human Breast Cancer

First, we investigated the expression of TNC in 35 cases of invasive ductal carcinomas. Dense TNC deposition was observed often in areas showing the scattered pattern (ie, the invading or EMT phenotype) of human breast cancer cells (Figure 1A), whereas solid-type large nests were negative for TNC (Figure 1B). TNC staining was dominantly positive in the stroma around and between the small cancer nests. The difference in positivity of TNC staining between solid and scattered types was highly significant (P < 0.0001; Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Dense TNC deposition is associated with an invading phenotype of human breast cancer cells. A: Invading cancer cells form small clusters scattered in TNC-positive cancer stroma. B: With large clusters showing smooth peripheral margins, TNC is not deposited in the stroma. Scale bar = 50 μm. C: TNC staining was frequently positive in the stroma with scattered cancer cells. The difference in positivity of TNC staining between solid and scattered types was significant (P < 0.0001).

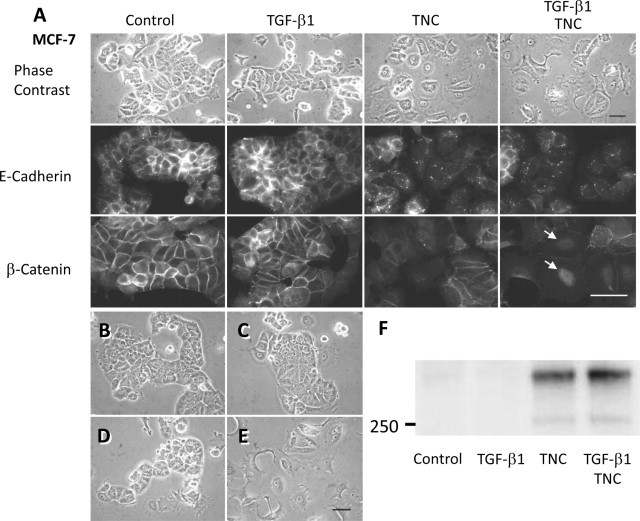

TNC Induces EMT-Like Change in MCF-7 Cells

It has been reported that TGF-β1 induces EMT change in some breast cancer cell lines.34 Here we investigated whether extrinsic addition of TNC and TGF-β1 to culture medium affects MCF-7 morphology (Figure 2A, top). MCF-7 cells normally showed tightly packed clusters, characteristic of epithelial cells. Although TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) treatment did not affect the morphology, the cells treated with TNC (10 μg/ml) for 64 hours appeared to be flattened and actively spreading, and they tended to lose their cell contacts. On costimulation with TNC and TGF-β1, most cells showed apparent loss of cell-cell adhesion and a migratory phenotype with production of lamellipodia and filopodia. This phenotypic change of MCF-7 cells was reversible because the morphology was restored to the epithelial phenotype within 3 days of replacement of the normal medium (Figure 2B). As a negative control, adding a supernatant of TNC solution after immunoprecipitation by TNC antibody and protein A beads did not cause the phenotypic change either without (Figure 2C) or with (Figure 2D) TGF-β1. Because we considered the possibility that intrinsic TGF-β produced by the cells may regulate EMT change induced by TNC alone, adding a neutralizing antibody to TGF-β (1D11, 50 μg/ml) was examined, but this did not impede the EMT change (Figure 2E). These results indicate a direct effect of TNC on EMT.

Figure 2.

TNC induces EMT-like change and E-cadherin/β-catenin translocation in MCF-7 cells. A: In the control and TGF-β1 treatment cases, MCF-7 cells form large clusters with tight intercellular connections. TNC was added to the medium when the cells were plated. Treatment for 64 hours induced cell-cell dissociation, and combined treatment with TGF-β1 and TNC resulted in stronger morphological change (top). On immunofluorescence of control cells, E-cadherin (middle) and β-catenin (bottom) are localized at plasma membranes of cell-cell junctions. TGF-β1 treatment did not affect localization, but TNC treatment reduced the membranous localization and the combined treatment–induced β-catenin translocation into nuclei (arrows). Scale bars = 50 μm. B: EMT change is reversible because the morphology was restored to the normal epithelial phenotype within 3 days after replacement of the normal medium. C–D: As a negative control, addition of a supernatant of TNC solution after immunoprecipitation by TNC antibody without TGF-β1 (C) or with TGF-β1 (D) did not cause phenotypic change. E: Addition of a neutralizing antibody to TGF-β (1D11, 50 μg/ml) into the medium containing TNC alone was examined, but this did not impede the EMT, indicating a direct effect of TNC on EMT. Scale bar = 50 μm. F: Immunoblot analysis of the lysate showed TNC deposition on cell surfaces and substrata in TNC- and TGF-β1/TNC-treated groups, although TNC was barely detectable in control and TGF-β1 alone groups.

Immunofluorescence of E-cadherin and β-catenin (Figure 2A, middle and bottom, respectively) demonstrated membrane staining at cell contacts in control cells and TGF-β1–treated cells. After treatment with TNC or both TGF-β1 and TNC, the membranous staining was diminished, whereas cytoplasmic staining was increased and nuclear staining of β-catenin was observed.

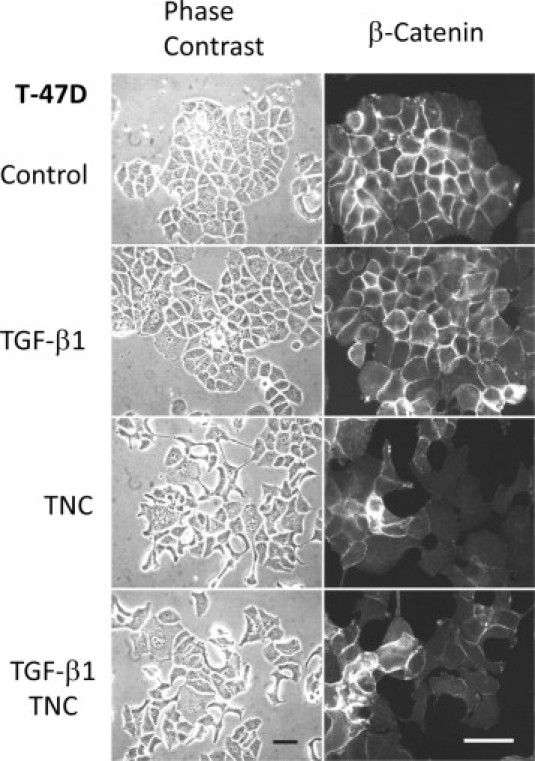

TNC deposition on the cell surfaces and substrata was detected in TNC-treated groups by immunoblot analysis, although MCF-7 cells did not synthesize TNC even after treatment by TGF-β1 alone (Figure 2F). Breast cancer cell line T-47D also showed EMT-like change by TNC treatment of 5 to 6 days. The EMT was exhibited at the margins of cell clusters, to a lesser extent than that for MCF-7 cells (Figure 3, left). Immunofluorescence demonstrated diminished β-catenin staining of intercellular contacts in the cells migrating outside the clusters (Figure 3, right).

Figure 3.

TNC also induces EMT-like change in T-47D cells. Breast cancer cell line T-47D showed EMT-like change by TNC and TGF-β1/TNC treatments for 5 to 6 days. The EMT was exhibited at the margin of cell cluster, to a lesser extent than for MCF-7 cells (left). Immunofluorescence exhibited reduced β-catenin staining of intercellular contacts in the cells moving outside the cluster (right). Scale bars = 50 μm.

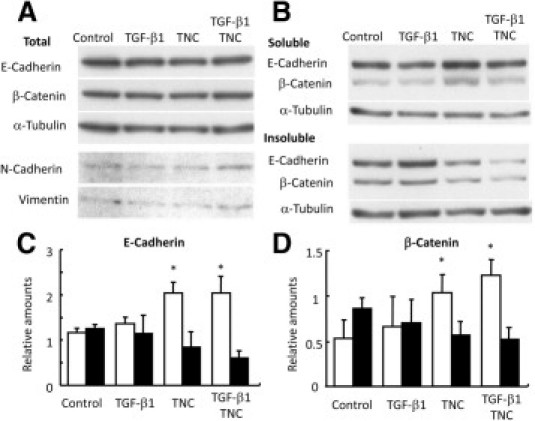

E-Cadherin and β-Catenin Are Translocated from the Membrane to the Cytoplasmic Fraction during EMT-Like Change

Immunoblot analysis of SDS lysates from MCF-7 cells demonstrated total amounts of E-cadherin and β-catenin proteins to be similar among the samples with or without treatments (Figure 4A). On Triton X-100 fractionation, E-cadherin and β-catenin amounts in the soluble fraction (cytoplasm/cytosol) were significantly increased in TNC- and TGF-β1/TNC-treated cells, whereas those in the insoluble fraction (cytoskeleton/membrane) were decreased (Figure 4B–D). These findings confirmed translocation from the membranous structures to the cytoplasm, as shown by immunofluorescence. We also performed immunoblot analysis of N-cadherin and vimentin as mesenchymal markers, but expression could barely be detected and there was little difference among the samples (Figure 4A). The phenotypic change without increased expression of mesenchymal markers was considered to be EMT-like change or incomplete EMT as previously proposed,6 rather than complete EMT.

Figure 4.

Immunoblot results showing translocation of E-cadherin and β-catenin to cytoplasm in MCF-7 cells after TNC treatment. A: Total amounts of E-cadherin and β-catenin extracted with SDS buffer do not differ among the samples. Expression of mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin is not up-regulated. B–D: On Triton X-100 fractionation [0.5% Triton X-100, 2.5 mmol/L EGTA, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, and 50 mmol/L PIPES (pH 6.2) at 37°C], the soluble fractions (open columns) show cytoplasmic/cytosolic localization, whereas the insoluble fractions (filled columns) demonstrate binding to the adherens junctions held by preserved cytoskeleton. TNC and TGF-β1/TNC treatments increased cytoplasmic/cytosolic fractions of E-cadherin (C) and β-catenin (D), indicating dissociation from the cytoskeleton/membrane. *P < 0.05.

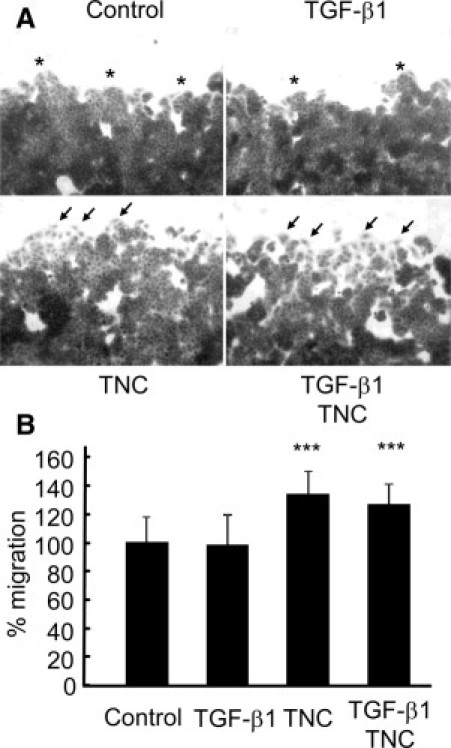

TNC Increases Migratory Activity in Wound Healing Assay

The cells were allowed to migrate for 24 hours after scratching the cell layer. The addition of TNC increased the number of migrating cells scattered from the wound edges (Figure 5A, arrows), possibly undergoing EMT. In contrast, cells in control and TGF-β1 treatment groups collectively migrated while remaining tightly bound to each other (Figure 5A, asterisks). The areas covered by the migrating cells in TNC and TGF-β1/TNC treatment groups were significantly more extensive than those in the control and TGF-β1 treatment groups, indicating enhanced cell migration by TNC (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

TNC induces scattered migration of MCF-7 cells from the edges and promotes migration in wound healing assay. A: TNC and TGF-β1/TNC treatments showed an increase in the number of scattered migrating cells (arrows) from the wound edges, whereas cells in the control and after TGF-β1 treatment groups exhibited tight clustering (asterisks). Scale bar = 50 μm. B: Migration of cells with TNC and TGF-β1/TNC treatments was significantly faster than that in the control or TGF-β1 treatment groups. Area newly covered by the migrating cells after wounding in the control group is denoted as 100%. Thirty-six fields per condition were examined. ***P < 0.001.

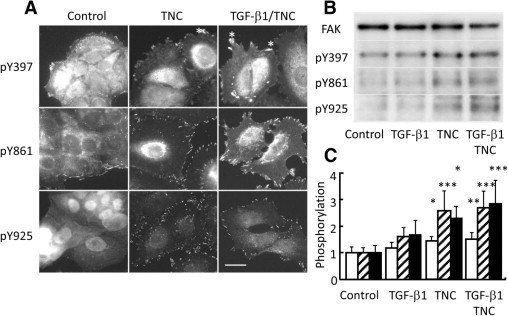

EMT Is Associated with Phosphorylation of FAK and SRC

We examined FAK phosphorylation at the sites Y397, Y861, and Y925 by immunofluorescence (Figure 6A) and immunoblot analysis (Figure 6B). TNC alone and the combined treatment with TGF-β1 caused an increase in the number of adhesion plaques positive for phosphorylated Y (pY) 397, Y861, and Y925. Immunostaining for pY397 was also observed in membrane ruffles (asterisks), which were more frequent in TNC-treated cells. Immunoblot analyses demonstrated that phosphorylation of FAK at Y397, Y861, and Y925 was increased significantly after treatment (Figure 6, B and C).

Figure 6.

TNC induces FAK phosphorylation. A: Immunofluorescent staining of MCF-7 cells with antibodies against phosphorylated FAK demonstrates an increase in the number of adhesion plaques positive for pY397, pY861, and pY925 with TNC and combined TGF-β1/TNC treatments. Bright fluorescence for FAK pY397 was visible in ruffled membranes and observed more frequently in the TNC- and TGF-β1/TNC-treated cells (asterisks). Scale bar = 20 μm. B: Immunoblot analyses of MCF-7 lysates using antibodies against FAK and the phosphorylated sites also show enhanced phosphorylation of FAK pY397, pY861, and pY925 after TNC and the combined treatments. C: Quantified data also showed that phosphorylation of FAK Y397 (open column), Y861 (striped columns), and Y925 (filled columns) in TNC-treated groups is significantly increased. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

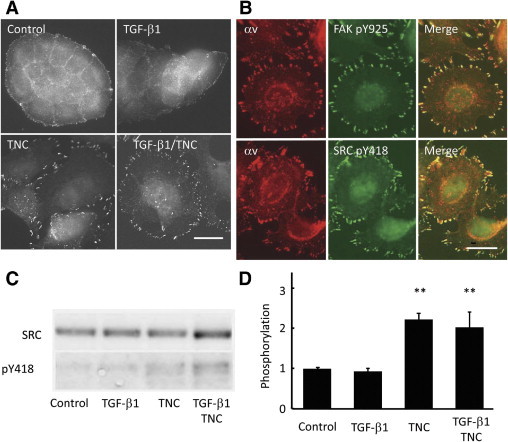

FAK Y397 phosphorylated by FAK itself is a binding site for SRC, and FAK Y861 and Y925 are substrate sites for SRC kinase.35 Because SRC is fully activated by phosphorylation of Y418,36 we examined localization of the phosphorylated SRC. Although detected only in small areas of peripheral margins of cell clusters in control and TGF-β1 alone cases, bright fluorescence was observed in adhesion plaques of TNC- and TGF-β1/TNC–treated cells (Figure 7A). The positivity was colocalized with αv-positive plaques (Figure 7B, bottom). FAK pY925 also was associated with αv fluorescence (Figure 7B, top). On immunoblot analyses, phosphorylation of SRC at Y418 was significantly increased after treatments of TNC alone and TGF-β1 and TNC together (Figure 7, C and D).

Figure 7.

TNC induces SRC activation accompanied by phosphorylation at Y418. A: Immunofluorescent staining of MCF-7 cells with antibodies against SRC pY418 demonstrates an increase in the number of adhesion plaques positive for pY418 with TNC and combined TGF-β1/TNC treatments. Scale bar = 20 μm. B: Immunofluorescent staining of FAK pY925 or SRC pY418 colocalizes with αv-positive adhesion plaques. Scale bar = 20 μm. C and D: Immunoblot analyses using antibodies against phosphorylated SRC show enhanced phosphorylation of Y418 after TNC and the combined treatments. **P < 0.01.

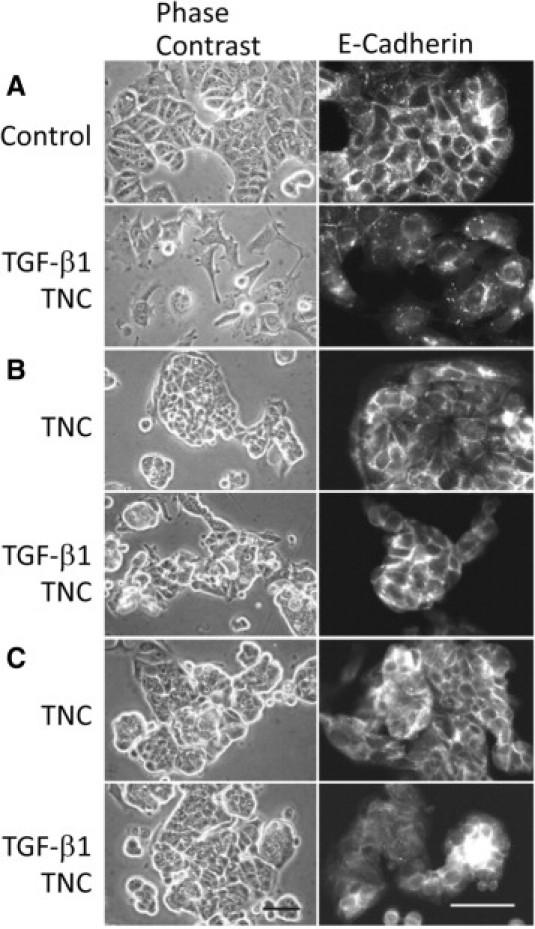

Anti–αv Antibody and a SRC Kinase Inhibitor Inhibit EMT-Like Change

We investigated whether signaling mediated by integrins and SRC activation regulates EMT. EMT induced by activated SRC with Y527F mutation is reported to require integrin signaling and to be blocked by neutralizing antibody against αv or β1 subunit.37 Adding a neutralizing antibody against the αv integrin subunit, AV1, blocked both morphological changes and E-cadherin translocation in TNC- and TGF-β1/TNC–treated cells (Figure 8B). After treatment with AV1, the attached cells on the substratum were reduced in number and tended to form smaller and rounded clusters. Neutralization of β1 integrin with P4C10 antibody, in contrast, did not block EMT after treatment with TGF-β1/TNC (data not shown). A SRC kinase inhibitor, pp2, also inhibited the EMT (Figure 8C). This treatment was also associated with a tendency to form rounded clusters.

Figure 8.

A neutralizing antibody against αv integrin and an SRC kinase inhibitor inhibit EMT change after the TNC alone and TGF-β1/TNC treatments. A: Phase contrast microscopy (left) and E-cadherin immunofluorescence (right) of MCF-7 cells without any treatment and after TGF-β1/TNC treatment are exhibited as controls. B: A neutralizing antibody against αv integrin (AV1) blocks EMT change after TNC and TGF-β1/TNC treatments. The attached cells on the substratum are reduced in number by AV1 treatment. Immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin was preserved in cell-cell contacts. C: The SRC kinase inhibitor (pp2) also inhibits the phenotypic change, with a tendency to form rounded clusters. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Discussion

EMT is believed to be a key mechanism in cancer progression whereby cancer cells acquire more aggressive behavior. Many studies on various cancer tissues have demonstrated dislocation and down-regulation of epithelial markers including E-cadherin, plakoglobin, and cytokeratin, as well as up-regulation of mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin and vimentin and expression of EMT transcriptional drivers, SNAI1/2 and TWIST1.2,11,12 These changes to mesenchymal phenotype may be correlated with invasiveness, metastatic potential, and poor outcome. Observations using breast cancer cell lines have shown that invasiveness in vitro and metastatic potential in vivo are associated with the expression of mesenchymal markers.38 However, whether classic EMT, including an ordered series of transcriptional events and a switch in cell fate observed in embryogenesis, occurs during tumor invasion and metastasis is still controversial.39,40In ductal carcinomas of the breast, immunohistochemical studies have not demonstrated any apparent correlation of E-cadherin expression with the scattered morphology, tumor type, nodal status, disease recurrence, distant metastases, or other prognostic factors.41–44 These observations suggest that a complete transition to a mesenchymal phenotype associated with transcriptional switching is not required for increased malignancy. Most advanced carcinomas may display some mesenchymal features but still retain well-differentiated epithelial cell characteristics. As an alternative, “incomplete EMT” with partial transition to the mesenchymal phenotype has been proposed.6 In cancer research, the term EMT has been more inclusively referred to as a change of cytological phenotype characterized as loss of cell junction and gain of migratory behaviors.40,45 In the present study, we demonstrated that deposition of TNC is frequently observed in invasion fronts of cancer cells with a scattered morphology, and that TNC induces EMT-like morphological change of MCF-7 cells, featuring loss of intercellular connections and an increasingly locomotive phenotype. The similar morphological change of MCF-7 cells on TNC substratum previously has been reported, but it was not mentioned as EMT.46 T-47D cells also showed EMT change by TNC treatment, although it required the longer treatment and occurred to a lesser extent than in MCF-7 cells. In addition, E-cadherin and β-catenin were found to be translocated from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm in immunofluorescence. Combined treatment with TNC and TGF-β1 caused more pronounced EMT-like change with β-catenin movement into nuclei. Immunoblot analyses of MCF-7 cells confirmed dissociation from membranes, but total amounts did not change. Mesenchymal markers, N-cadherin and vimentin, were not up-regulated. This EMT-like change induced by TNC treatment is compatible with incomplete EMT of cancer cells.6 Similarly, NMuMG (normal murine mammary gland) cells also transform to spindle cell morphology showing delocalization of E-cadherin without down-regulation by TGF-β treatment.47

Previous studies have shown that TGF-β treatment triggers EMT (or EMT-like change) in various cancer cells, including breast epithelial cells.1,34 In this study, however, TGF-β1 treatment alone did not induce morphological change in MCF-7 or T-47D cells, keeping our results in line with a previous report.34 Cancer cell lines often produce and secrete TNC, but both MCF-7 and T-47D do not.24,31 In EMT-induced cells treated with TGF-β alone, sufficient amounts of TNC may be produced by the cells themselves to evoke EMT. Transformed mouse mammary epithelial cells that undergo TGF-β-induced EMT show enhanced TNC production and matrix deposition.48 In this study, TNC deposition on cell surfaces and substrata of MCF-7 cells was observed in TNC-treated groups, whereas the deposition was hardly detected after treatment of TFG-β1 alone. A neutralizing antibody of TGF-βs could not inhibit EMT by TNC treatment. These findings suggest that TNC directly induces EMT and that TNC and TGF-β are collaboratively responsible for EMT-like events in breast cancer cells. In situ hybridization studies have demonstrated that not only cancer cells but also stromal cells synthesize TNC and TGF-β in the cancer tissues.18,49 In a recent study, co-culture of MCF-7 cells with fibroblasts isolated from breast cancer tissues or interface zone adjacent to the cancer tissues for 1 week has demonstrated an induction of EMT-like state characterized by E-cadherin down-regulation and up-regulation of N-cadherin and vimentin in cancer cells and promotion of the cancer cell migration. So although we also tried TNC treatment of MCF-7 cells for up to 12 days, vimentin filament formation in the cells was not observed (data not shown). TNC and TGF-β produced by the fibroblasts may be partially responsible for the EMT process of the co-culture, whereas the transcriptional alteration is caused by other substances.50 An interaction of cancer and stromal cells in the invading border may provide a microenvironment that induces the EMT.

Our immunofluorescence and immunoblot results demonstrated that TNC and TNC/TGF-β treatments cause increased phosphorylation of FAK at Y397, Y861, and Y925 in cells undergoing EMT. Whereas Y397 is autophosphorylated, Y861 and Y925 are the substrate sites for activated SRC.34 SRC can bind to FAK pY397, and this is activated by disruption of intramolecular interactions within SRC.51 The full activation requires intermolecular autophosphorylation of Y418 within the catalytic domain.36 Elevated phosphorylation of Y418 in TGF-β/TNC–treated cells can lead to SRC activation, followed by increased phosphorylation of FAK at Y861 and Y925. It has been demonstrated that phosphorylation of FAK Y925 is a major event associated with E-cadherin deregulation in EMT of KM12C colon cancer cells transfected with active SRC gene with Y527F mutation.37,52 SRC/FAK signaling is considered to be a mediator of cross-talk between cadherin- and integrin-mediated adhesion.10 E-Cadherin delocalization induced by SRC activation requires integrin signaling from αv or β1 subunits.37 The TNC-induced EMT in our study could be abolished by treatment with an SRC inhibitor or a neutralizing antibody for the αv subunit, indicating involvement of a regulatory mechanism similar to SRC-induced EMT. Although integrins α2/7/8/9β1 bind to TNC13 and may mediate the signaling, integrin β1 antibody did not block EMT-like change by TGF-β/TNC treatment. Focal adhesions containing αv subunits colocalize with activated SRC and FAK, as shown in this study, and may form essential signaling domains for EMT. Whereas integrins αvβ1/3/6 are known to be TNC receptors,13 up-regulation of β6 integrin subunit following TGF-β treatment induces EMT change in colon cancer cell line.53 In our preliminary study, integrin β6 subunit was also up-regulated by TGF-β in MCF-7 cells, whereas either neutralization of αvβ6 integrin by an antibody clone 10D5 or β6 knockdown using siRNA did not impede the EMT-like change after TGF-β/TNC treatment (data not shown). Further investigations on the relationship of the integrins to signaling events during EMT change appear warranted. In contrast, cell detachment from substratum is reported to evoke SRC activation with phosphorylation of Y418 in anoikis-resistant lung tumor cells.54 Counteradhesive properties of TNC might yield SRC activation by modulation of integrin signaling in cancer cells.

In addition, epidermal growth factor receptors also bind to epidermal growth factor–like repeats of TNC with low affinity. The binding yields autophosphorylation and increased activity of the receptor tyrosine kinase, followed by activation of related signal pathways.55 TNC also promotes clustering of epidermal growth factor receptors to focal adhesions, which is associated with signaling cross-talk between the receptors and integrins.56 This could also up-regulate kinase activity of SRC.51 In T98G glioma cells on TNC-containing substratum, activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase and Wnt pathways has been observed.57 RhoA activation is suppressed in fibroblasts on TNC matrix.58 These alterations of signaling pathways are considered to be generally responsible for EMT and to be promoted by activated SRC.9,59 Activation of SRC and FAK is closely related to enhanced cytoskeletal reorganization that facilitates cell migration as well as EMT change.10,35,36 MCF-7 cells under the TNC condition showed faster migration in wound closure as previously reported using other cell lines.22,25

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that TNC is preferentially deposited in the stroma with scattered and small cancer nests in vivo and induces EMT-like change showing loss of cell-cell junctions and gain of migratory behaviors in breast cancer cells in vitro. The cancer cell phenotype could be dynamically converted by spatiotemporal expression of TNC. TNC expression in invasion border is reported to be a predictor of distant metastasis and local recurrence in breast cancer.27,28 The environment of TNC-rich extracellular matrix in the cancer tissues could evoke reduced cell contacts, forming scattered and smaller cancer nests, and promote cell motility at invading fronts, accounting for the correlation of TNC positivity with poorer outcome of patients with breast cancers. TNC may, thus, be a key molecule responsible for malignant behavior of breast cancers, providing a target for future therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgment

We thank Ms. Miyuki Namikata for her technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (21590368).

K.N. and X.Z. contributed equally to this work.

T.Y. receives royalties from Immuno-Biologican Lab-Japan.

Current address of Y.K.: Department of Pathology, Kawasaki Medical School Hospital, Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan.

References

- 1.Savagner P. Leaving the neighborhood: molecular mechanisms involved during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Bioessays. 2001;23:912–923. doi: 10.1002/bies.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiery J.P., Acloque H., Huang R.Y., Nieto M.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum B., Settleman J., Quinlan M.P. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states in development and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J., Weinberg R.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson E.W., Newgreen D.F., Tarin D. Carcinoma invasion and metastasis: a role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition? Cancer Res. 2005;65:5991–5995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen J.J., Rajasekaran A.K. Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8319–8326. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse J.C., Kalluri R. Mechanisms of metastasis: epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and contribution of tumor microenvironment. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:816–829. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Wever O., Pauwels P., De Craene B., Sabbah M., Emami S., Redeuilh G., Gespach C., Bracke M., Berx G. Molecular and pathological signatures of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions at the cancer invasion front. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:481–494. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber M.A., Kraut N., Beug H. Molecular requirements for epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avizienyte E., Frame M.C. Src and FAK signalling controls adhesion fate and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peinado H., Olmeda D., Cano A. Snail: Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeisberg M., Neilson E.G. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orend G., Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Tenascin-C induced signaling in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;244:143–163. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crossin K.L., Hoffman S., Grumet M., Thiery J.P., Edelman G.M. Site-restricted expression of cytotactin during development of the chicken embryo. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1917–1930. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker R.P., McKay S.E. The expression of tenascin by neural crest cells and glia. Development. 1991;112:1031–1039. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.4.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugi Y., Markwald R.R. Formation and early morphogenesis of endocardial endothelial precursor cells and the role of endoderm. Dev Biol. 1996;175:66–83. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyer A.S., Erickson C.P., Runyan R.B. Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in the embryonic heart is mediated through distinct pertussis toxin-sensitive and TGFbeta signal transduction mechanisms. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:81–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199901)214:1<81::AID-DVDY8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson M.W. Palate development. Development. 1988;103(Suppl):41–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalembey I., Yoshida T., Iriyama K., Sakakura T. Analysis of tenascin mRNA expression in the murine mammary gland from embryogenesis to carcinogenesis: an in situ hybridization study. Int J Dev Biol. 1997;41:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida T., Matsumoto E., Hanamura N., Kalembeyi I., Katsuta K., Ishihara A., Sakakura T. Co-expression of tenascin and fibronectin in epithelial and stromal cells of benign lesions and ductal carcinomas in the human breast. J Pathol. 1997;182:421–428. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199708)182:4<421::AID-PATH886>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishihara A., Yoshida T., Tamaki H., Sakakura T. Tenascin expression in cancer cells and stroma of human breast cancer and its prognostic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1035–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida T., Yoshimura E., Numata H., Sakakura Y., Sakakura T. Involvement of tenascin-C in proliferation and migration of laryngeal carcinoma cells. Virchows Arch. 1999;435:496–500. doi: 10.1007/s004280050433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsunoda T., Inada H., Kalembeyi I., Imanaka-Yoshida K., Sakakibara M., Okada R., Katsuta K., Sakakura T., Majima Y., Yoshida T. Involvement of large tenascin-C splice variants in breast cancer progression. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1857–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64320-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancox R.A., Allen M.D., Holliday D.L., Edwards D.R., Pennington C.J., Guttery D.S., Shaw J.A., Walker R.A., Pringle J.H., Jones J.L. Tumour-associated tenascin-C isoforms promote breast cancer cell invasion and growth by matrix metalloproteinase-dependent and independent mechanisms. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvo A., Catena R., Noble M.S., Carbott D., Gil-Bazo I., Gonzalez-Moreno O., Huh J.I., Sharp R., Qiu T.H., Anver M.R., Merlino G., Dickson R.B., Johnson M.D., Green J.E. Identification of VEGF-regulated genes associated with increased lung metastatic potential: functional involvement of tenascin-C in tumor growth and lung metastasis. Oncogene. 2008;27:5373–5384. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalembeyi I., Inada H., Nishiura R., Imanaka-Yoshida K., Sakakura T., Yoshida T. Tenascin-C upregulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 in breast cancer cells: direct and synergistic effects with transforming growth factor beta1. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:53–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahkola T., Toivonen T., von Smitten K., Blomqvist C., Virtanen I. Expression of tenascin in invasion border of early breast cancer correlates with higher risk of distant metastasis. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:445–447. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961220)69:6<445::AID-IJC4>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahkola T., Toivonen T., Virtanen I., von Smitten K., Nordling S., von Boguslawski K., Haglund C., Nevanlinna H., Blomqvist C. Tenascin-C expression in invasion border of early breast cancer: a predictor of local and distant recurrence. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1507–1513. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jahkola T., Toivonen T., Nordling S., von Smitten K., Virtanen I. Expression of tenascin-C in intraductal carcinoma of human breast: relationship to invasion. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirl G., Hermann M., Ekblom P., Fässler R. Mammary epithelial cell differentiation in vitro is regulated by an interplay of EGF action and tenascin-C downregulation. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2445–2456. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawakatsu H., Shiurba R., Obara M., Hiraiwa H., Kusakabe M., Sakakura T. Human carcinoma cells synthesize and secrete tenascin in vitro. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83:1073–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb02724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadot E., Simcha I., Shtutman M., Ben-Ze'ev A., Geiger B. Inhibition of beta-catenin-mediated transactivation by cadherin derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15339–15344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shtutman M., Levina E., Ohouo P., Baig M., Roninson I.B. Cell adhesion molecule L1 disrupts E-cadherin-containing adherens junctions and increases scattering and motility of MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11370–11380. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown K.A., Aakre M.E., Gorska A.E., Price J.O., Eltom S.E., Pietenpol J.A., Moses H.L. Induction by transforming growth factor-beta1 of epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a rare event in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R215–R231. doi: 10.1186/bcr778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLean G.W., Carragher N.O., Avizienyte E., Evans J., Brunton V.G., Frame M.C. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer—a new therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:505–515. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roskoski R., Jr Src kinase regulation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avizienyte E., Wyke A.W., Jones R.J., McLean G.W., Westhoff M.A., Brunton V.G., Frame M.C. Src-induced de-regulation of E-cadherin in colon cancer cells requires integrin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:632–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blick T., Widodo E., Hugo H., Waltham M., Lenburg M.E., Neve R.M., Thompson E.W. Epithelial mesenchymal transition traits in human breast cancer cell lines. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:629–642. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarin D., Thompson E.W., Newgreen D.F. The fallacy of epithelial mesenchymal transition in neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5996–6000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowin P., Welch D.R. Breast cancer progression: controversies and consensus in the molecular mechanisms of metastasis and EMT. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:99–102. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashizume R., Koizumi H., Ihara A., Ohta T., Uchikoshi T. Expression of β-catenin in normal breast tissue and breast carcinoma: a comparative study with epithelial cadherin and α-catenin. Histopathology. 1996;29:139–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker C., Rampaul R.S., Pinder S.E., Bell J.A., Wencyk P.M., Blamey R.W., Nicholson R.I., Robertson J.F. E-cadherin as a prognostic indicator in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1958–1963. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovacs A., Dhillon J., Walker R.A. Expression of P-cadherin, but not E-cadherin or N-cadherin, relates to pathological and functional differentiation of breast carcinomas. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:318–322. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.6.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez M.A., Pinder S.E., Wencyk P.M., Bell J.A., Elston C.W., Nicholson R.I., Robertson J.F., Blamey R.W., Ellis I.O. An immunohistochemical examination of the expression of E-cadherin, α- and β/γ-catenins, and α2-and β1-integrins in invasive breast cancer. J Pathol. 1999;187:523–529. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199904)187:5<523::AID-PATH296>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuji T., Ibaragi S., Hu G.F. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell cooperativity in metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7135–7139. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin D., Brown-Luedi M., Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Tenascin-C signaling through induction of 14-3-3 tau. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:171–175. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bakin A.V., Tomlinson A.K., Bhowmick N.A., Moses H.L., Arteaga C.L. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36803–36810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maschler S., Grunert S., Danielopol A., Beug H., Wirl G. Enhanced tenascin-C expression and matrix deposition during Ras/TGF-beta-induced progression of mammary tumor cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:3622–3633. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nerlich A.G., Wiest I., Wagner E., Sauer U., Schleicher E.D. Gene expression and protein deposition of major basement membrane components and TGF-beta 1 in human breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:4443–4449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao M.Q., Kim B.G., Kang S., Choi Y.P., Park H., Kang K.S., Cho N.H. Stromal fibroblasts from the interface zone of human breast carcinomas induce an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like state in breast cancer cells in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3507–3514. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas S.M., Brugge J.S. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunton V.G., Avizienyte E., Fincham V.J., Serrels B., Metcalf C.A., 3rd, Sawyer T.K., Frame M.C. Identification of Src-specific phosphorylation site on focal adhesion kinase: dissection of the role of Src SH2 and catalytic functions and their consequences for tumor cell behavior. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1335–1342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bates R.C., Bellovin D.I., Brown C., Maynard E., Wu B., Kawakatsu H., Sheppard D., Oettgen P., Mercurio A.M. Transcriptional activation of integrin beta6 during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition defines a novel prognostic indicator of aggressive colon carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:339–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI23183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei L., Yang Y., Zhang X., Yu Q. Altered regulation of Src upon cell detachment protects human lung adenocarcinoma cells from anoikis. Oncogene. 2004;23:9052–9061. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swindle C.S., Tran K.T., Johnson T.D., Banerjee P., Mayes A.M., Griffith L., Wells A. Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats of human tenascin-C as ligands for EGF receptor. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:459–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones P.L., Crack J., Rabinovitch M. Regulation of tenascin-C, a vascular smooth muscle cell survival factor that interacts with the alpha v beta 3 integrin to promote epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation and growth. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:279–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruiz C., Huang W., Hegi M.E., Lange K., Hamou M.F., Fluri E., Oakeley E.J., Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Orend G. Growth promoting signaling by tenascin-C. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7377–7385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wenk M.B., Midwood K.S., Schwarzbauer J.E. Tenascin-C suppresses Rho activation. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:913–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finn R.S. Targeting Src in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1379–1386. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]