See related article on page 828

As long ago as 1887, Podwyssozki1 noted that extensive cellular regeneration could take place in the renal tubules after injury. In honor of the Kantian thought, he termed this phenomenon regeneration per intussusceptionem, suggesting that regenerating cells were “growing from within”1 and that novel tubular cells could be derived from cells that survived. However, the most interesting and detailed description of tubular regeneration was published in 1928 by Hunter,2 who reported that after injury, in adult human kidneys “the tubules are almost completely relined by a new and atypical cell differing very markedly from the original epithelium in size, shape and staining qualities ... The regenerated cells have the staining reaction of embryonic epithelium.”p 465–466

The origin of these “atypical cells” in regenerating tubular epithelium was largely debated throughout the past century. In recent years, several studies have suggested that after injury, differentiated tubular cells proliferate and migrate to replace the neighboring dead cells.3 However, to explain the substantially modified phenotype shown by the regenerating tubular epithelium, these studies hypothesized that tubular cells underwent a process of “dedifferentiation.”3 Indeed, in healthy adult human kidneys, renal tubular epithelial cells are columnar and cuboidal and express cytokeratin and adherens junctions that contribute to apical-basal polarity.3 After injury, regenerating tubular cells lose apical-basal polarity, show flattened and elongated morphologic features, and express the intermediate filament vimentin, thus acquiring a phenotype that is similar to those of the metanephric mesenchyme-derived renal embryonic progenitors.3,4 This indicates that the regenerative process is associated with a reversal to a less differentiated phenotype, followed by redifferentiation, when the mesenchymal markers are lost, epithelial markers return, and physiologic function is restored.3,4

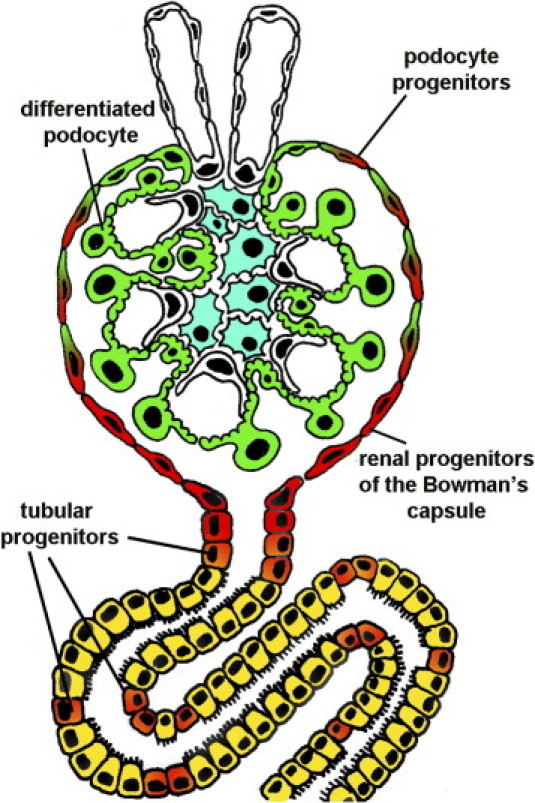

In the current issue of The American Journal of Pathology, Lindgren et al5 propose an alternative hypothesis to explain the origin of atypical cells in regenerating tubular epithelium. Indeed, almost a century after Hunter's observations, these authors suggest the existence in adult human kidneys of rare embryonic-like tubular progenitors scattered among the more differentiated proximal tubular cells. Lindgren et al5 isolated from healthy adult human renal tissue a cell population displaying high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, which is considered as a shared property of stem/progenitor cells in multiorgan systems.6 By gene expression profiling of the aldehyde dehydrogenase high and low cell fractions isolated and by subsequent immunohistochemical interrogation of renal cortical tissues, they delineated a rare cell population distributed in the epithelial layer of the proximal tubules in healthy adult human kidneys defined by coexpression of CD133 and CD24, two markers that selectively characterize the recently identified population of renal progenitors in Bowman's capsule (Figure 1).7–10 In adult human kidney, CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule exhibit self-renewal potential, and they consist of a hierarchical population of progenitors that are arranged in a precise sequence in Bowman's capsule and exhibit heterogeneous potential for differentiation and regeneration.11 Cells localized to the urinary pole that express CD133 and CD24 but not podocalyxin (PDX) or other podocyte markers (CD133+CD24+PDX− cells) could regenerate tubular cells and podocytes. In contrast, cells localized between the urinary pole and the vascular pole that expressed both progenitor and podocyte markers (CD133+CD24+PDX+) could regenerate only podocytes.11 Finally, cells localized to the vascular pole did not exhibit progenitor markers but displayed phenotypic features of fully differentiated podocytes (CD133−CD24−PDX+ cells) (Figure 1).11 More recently, genetic tagging provided the proof of concept that the renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule represent a hierarchical population of stem/progenitor cells also in rodents and that they can proliferate and progressively differentiate into podocytes from the urinary pole to the vascular pole.12 However, evidence that CD133+CD24+ progenitors of Bowman's capsule can also regenerate tubular cells has currently been provided only in humans.7–11 Indeed, CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors purified by adult human kidneys regenerated tubular structures in different portions of the nephron and reduced the morphologic and functional kidney damage in SCID mice affected by acute tubular necrosis, suggesting that these cells can participate in tubular regeneration in adult human kidneys.7–9 In addition, several previous studies have demonstrated that the proximal tubule arises at a variety of angles from Bowman's capsule and that at least one part of the tubuloglomerular junction has an area of intermediate appearance, with prominent microvilli on parietal cells in humans, mammals, and fish.10,13 These findings further confirm that renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule can, indeed, change into not only podocytes but also tubular epithelial cells, and it has been previously suggested that this might particularly occur as the kidney grows, during severe renal disorders,13 and during aging.13 The existence of a bipotent progenitor at the urinary pole of Bowman's capsule (Figure 1) is also in agreement with observations performed in adult exocrine glands, where adult stem cell compartments containing bipotent progenitors are usually localized at the point of connection between the lobule, which produces the secretion, and the duct, which modifies the secretion and collects it in the external of the gland.14 However, the duct of the exocrine gland is usually short, whereas the tubular part of the nephron is very long, which suggests that the stem cell compartment localized at the beginning of the tubular structure probably does not represent the unique source of regeneration of the tubular part of the nephron. The results of the study by Lindgren et al5 provide an intriguing novel hypothesis that rare CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors may localize in the tubule and proliferate and differentiate after tubular injury (Figure 1). Accordingly, tubular epithelium regenerating on acute tubular necrosis displayed long stretches of CD133+CD24+ cells, further substantiating that the atypical cells that are repairing tubular epithelium may simply represent the result of proliferation and differentiation of CD133+CD24+ tubular progenitors.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms of tubular regeneration. CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors (red) are localized at the urinary pole and are in close contiguity with tubular renal cells (yellow) at the tubuloglomerular junction and with podocytes (green) at the vascular stalk. CD133+CD24+ tubular progenitors (orange) displaying mixed features of renal progenitors (red) and proximal tubular cells (yellow) localize at the tubuloglomerular junction and are scattered among more differentiated tubular cells. These tubular progenitors may proliferate and differentiate after tubular injury to replace dead cells. In contrast, CD133+CD24+ podocyte progenitors (red/green) display features of either renal progenitors (red) or podocytes (green) and localize between the urinary pole and the vascular stalk.

The strength of this hypothesis is further supported by the long list of markers that are uniquely shared by the scattered CD133+CD24+ tubular progenitors and their counterparts of Bowman's capsule but not by all the other epithelial cells of the nephron.5 Indeed, functional and bioinformatics analyses allowed a detailed characterization of the transcriptome of these cells, which indicated that they are endowed with a robust phenotype allowing increased resistance to acute tubular injury.5 More important, the renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule and their tubular counterparts are characterized also by expression of cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 19, the antiapoptotic gene BCL2, the regeneration-promoting molecule MYOF, and vimentin, suggesting a unique phenotype5 characterized by coexpression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers, which has previously been reported for the renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule.6 Coexpression of cytokeratin and vimentin, and of the renal progenitor's markers CD133 and CD24, is also a distinctive feature of the renal embryonic progenitor.13,15 Indeed, CD133+CD24+ cells also represent common progenitors of tubular cells and podocytes during kidney development,13,15 as shown by the observation that CD133 and CD24 coexpression identifies a subset of cells in the primordial nephron that display self-renewal and multidifferentiation potential.13,15 CD133+CD24+ progenitors are located in condensed mesenchyme-derived primordial structures, primary vesicles, comma-shaped bodies, and S-shaped bodies.13,15 However, when the primordial nephron elongates and a primitive vascular tuft becomes evident in the cup-shaped glomerular precursor region, a cluster of CD133+CD24+ progenitors can be localized only at the urinary pole of Bowman's capsule.13,15 It is, however, possible that during the elongation process, which requires CD133+CD24+ proliferation and differentiation, some of the CD133+CD24+ cells that constitute the S-shaped body remain included as rare single cells in the maturing nephron and constitute the scattered CD133+CD24+ tubular progenitors.

The results of the study by Lindgren et al5 are also in agreement with those of lineage tracing experiments performed by Humphreys et al16 using transgenic mice to mark cells derived from the renal embryonic progenitors in adult kidneys. In this model, a fusion protein leads to constitutive and heritable expression of a marker gene such that all metanephric mesenchyme–derived renal epithelial cells, from Bowman's capsule to the junction of the connecting segment and the collecting duct, are heritably labeled.16 In contrast, the entire interstitial compartment and the collecting ducts remain unlabeled.16 After the induction of acute kidney injury, the repair of injured nephrons was accomplished by intrinsic cells localized in the cortical nephron, suggesting that repair of injured tubules is accomplished only by resident renal epithelial cells that represent the direct progeny of the renal embryonic progenitor.16 These results also demonstrated that the contribution of any stem/progenitor cell localized outside the cortical nephron for repopulation of the tubular epithelium is irrelevant. This is noteworthy because previous studies have suggested that progenitor cells with regenerating potential for renal epithelium could be located in the renal interstitium or among cells of the collecting ducts.8–10,17 The absence of label dilution after injury and repair also definitively demonstrates that bone marrow–derived cells do not directly contribute to renal repair.8–10,17

Finally, the study by Lindgren et al5 provides another provocative observation, which is demonstration of the close relationship between the transcriptome of these tubular progenitors and the one derived by papillary renal cell carcinomas. This is further confirmed by the observation that the combination of cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 19, and vimentin, which is a unique feature of CD133+CD24+ renal progenitor in the adult human kidney, is used by pathologists to discriminate papillary renal cell carcinomas from all other renal cell carcinoma subtypes.18 Papillary renal cell carcinomas are derived from cells of the proximal convoluted tubule similar to clear renal cell carcinomas, but they show a distinct immunostaining phenotype.18 Thus, these observations raise the provocative hypothesis that papillary renal cell carcinomas may directly derive from CD133+CD24+ renal tubular progenitors, whereas clear renal cell carcinomas may derive from other more differentiated proximal tubular cells. Accordingly, Lindgren et al5 provided evidence of strong CD133 expression by the papillary renal cell carcinomas analyzed. These results are also in agreement with the concept that altered growth and/or differentiation of CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors may also be responsible for the generation of disorders.10,19 This concept is widely accepted in several stem cell systems, and it has recently been reported for the CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule and for the CD133+CD24+ podocyte–committed progenitors, which can generate hyperplastic glomerular lesions of different types of podocytopathies and in crescentic glomerulonephritis and eventually lead to glomerulosclerosis.10,19

Although the study by Lindgren et al5 provides convincing answers to many of the questions we had about tubular regeneration and opens a novel interesting hypothesis for the pathogenesis of some subtypes of renal cell carcinomas, there are several questions that still need to be answered. Direct proof of the regenerative capacity of these CD133+CD24+ tubular progenitors has to be provided using in vivo models of acute tubular injury. This will require the identification of novel markers that may allow distinction between the CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule and those scattered in the tubular portion of the nephron and a direct study of the two populations, as has been performed for CD133+CD24+ podocyte–committed progenitors using the podocyte marker PDX.11 This may allow us to also define the tubular lineage of the stem cell compartment of the kidney and to understand how it is generated and regulated. In addition, genetic tagging experiments are required to provide the proof of concept that this population participates in tubular regeneration after acute and/or chronic tubular injury. However, using transgenic mouse lines that express LacZ or Cre-recombinase under the control of an NFATc1 autoregulatory enhancer, a previous study already suggested the putative existence of a scattered progenitor cell population that proliferates to repopulate the proximal tubule after injury with HgCl2.20 This putative progenitor population is acutely resistant to apoptosis and subsequently participates in regeneration of the damaged proximal tubule in rodents.20 Finally, further studies are necessary to evaluate the possibility that different subtypes of renal cell carcinomas may be generated by cancer stem cells that are directly derived from distinct stages of renal stem cell differentiation toward the tubular lineage.

The existence of a stem cell compartment and of putative tubular progenitors does not exclude the existence of further regenerative strategies to repair injured tubular cells in adult mammalian kidneys. Indeed, we have learned from planarians, fish, and amphibians, which exhibit high regenerative potential, that different strategies exist to regenerate injured organs and tissues. For example, working organ cells that normally do not divide can multiply and grow to replenish lost tissue, as occurs in injured salamander hearts.21 In addition, specialized cells can undo their training and assume a more pliable form that can replicate and later respecialize to reconstruct a missing part. Salamanders and newts take this approach to heal and rebuild a severed limb, as do zebra fish to mend clipped fins.21 Finally, pools of stem cells can step in to perform required renovations. Planaria tap into this resource when reconstructing themselves.21 Although it is not yet clear how regenerative strategies that are observed during the early phases of evolution are applied in higher vertebrates, animals exploit different strategies for regeneration. Converging data suggest that usually more than one mechanism is involved in regeneration of a tissue10,13 because this confers an advantage during evolution. Further studies are needed to understand whether different mechanisms of regeneration contribute to tubular repair during acute and/or chronic renal disorders. However, the existence of a stem cell compartment suggests that novel treatments aimed at promoting the regenerative capacities of the kidney could conceivably be possible. Before that can happen, we will have to understand the signals that control the growth and differentiation of CD133+CD24+ renal progenitors.

Footnotes

Supported by the European Research Council starting grant under the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), European Research Council grants 205027 and 223007, and the Tuscany Ministry of Health (P.R.).

References

- 1.Podwyssozki W Jr: Ueber die Regeneration der Epithelien der Leber, der Niere, der Speichel- und Meibom'schen Drfisen unter pathologisehen Bedingungen, Fortschr. d. Med., 1885, iii, 630; Die Gesetze der Regeneration der Drfisen Epithelien unter physiologischen und pathologischen Bedingungen, ibid., 1887, v, 433

- 2.Hunter W.C. Regeneration of tubular epithelium in the human kidney following injury by mercuric chloride. Ann Intern Med. 1928;1:463–469. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonventre J.V. Dedifferentiation and proliferation of surviving epithelial cells in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;1(Suppl):S55–S61. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000067652.51441.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gröne H.J., Weber K., Gröne E., Helmchen U., Osborn M. Coexpression of keratin and vimentin in damaged and regenerating tubular epithelia of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 1987;129:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindgren D., Boström A.K., Nilsson K., Hansson J., Sjölund J., Möller C., Jirström K., Nilsson E., Landberg G., Axelson H., Johansson M.E. Isolation and characterization of progenitor-like cells from human renal proximal tubules. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:828–837. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreb J.S. Aldehyde dehydrogenase as a marker for stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2008;3:237–246. doi: 10.2174/157488808786734006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagrinati C., Netti G.S., Mazzinghi B., Lazzeri E., Liotta F., Frosali F., Ronconi E., Meini C., Gacci M., Squecco R., Carini M., Gesualdo L., Francini F., Maggi E., Annunziato F., Lasagni L., Serio M., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman's capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzinghi B., Ronconi E., Lazzeri E., Sagrinati C., Ballerini L., Angelotti M.L., Parente E., Mancina R., Netti G.S., Becherucci F., Gacci M., Carini M., Gesualdo L., Rotondi M., Maggi E., Lasagni L., Serio M., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Essential but differential role for CXCR4 and CXCR7 in the therapeutic homing of human renal progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:479–490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagrinati C., Ronconi E., Lazzeri E., Lasagni L., Romagnani P. Stem-cell approaches for kidney repair: choosing the right cells. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasagni L., Romagnani P. Glomerular epithelial stem cells: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1612–1619. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronconi E., Sagrinati C., Angelotti M.L., Lazzeri E., Mazzinghi B., Ballerini L., Parente E., Becherucci F., Gacci M., Carini M., Maggi E., Serio M., Vannelli G.B., Lasagni L., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appel D., Kershaw D., Smeets B., Yuan G., Fuss A., Frye B., Elger M., Kriz W., Floege J., Moeller M.J. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romagnani P. Toward the identification of a “renopoietic system”? Stem Cells. 2009;27:2247–2253. doi: 10.1002/stem.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanpain C., Horsley V., Fuchs E. Epithelial stem cells: turning over new leaves. Cell. 2007;128:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazzeri E., Crescioli C., Ronconi E., Mazzinghi B., Sagrinati C., Netti G.S., Angelotti M.L., Parente E., Ballerini L., Cosmi L., Maggi L., Gesualdo L., Rotondi M., Annunziato F., Maggi E., Lasagni L., Serio M., Romagnani S., Vannelli G.B., Romagnani P. Regenerative potential of embryonic renal multipotent progenitors in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3128–3138. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphreys B.D., Valerius M.T., Kobayashi A., Mugford J.W., Soeung S., Duffield J.S., McMahon A.P., Bonventre J.V. Intrinsic epithelial cells repair the kidney after injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little M.H. Tracing the life of the kidney tubule: re-establishing dogma and redirecting the options. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:191–192. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skinnider B.F., Folpe A.L., Hennigar R.A., Lim S.D., Cohen C., Tamboli P., Young A., de Peralta-Venturina M., Amin M.B. Distribution of cytokeratins and vimentin in adult renal neoplasms and normal renal tissue: potential utility of a cytokeratin antibody panel in the differential diagnosis of renal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:747–754. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000163362.78475.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smeets B., Angelotti M.L., Rizzo P., Dijkman H., Lazzeri E., Mooren F., Ballerini L., Parente E., Sagrinati C., Mazzinghi B., Ronconi E., Becherucci F., Benigni A., Steenbergen E., Lasagni L., Remuzzi G., Wetzels J., Romagnani P. Renal progenitor cells contribute to hyperplastic glomerular lesions of different types of podocytopathies and in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2593–2603. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langworthy M., Zhou B., de Caestecker M., Moeckel G., Baldwin H.S. NFATc1 identifies a population of proximal tubule cell progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:311–321. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davenport R.J. What controls organ regeneration? Science. 2005;309:84. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5731.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]