Abstract

Cytoglobin (Cygb) is a novel member of the vertebrate globin superfamily. Although it is expressed in splanchnic fibroblasts of various organs, details of its function remain unknown. In the present study, kidney ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) increased the number of Cygb-positive cells per area and up-regulated Cygb mRNA and protein expression in kidney cortex tissues. Similarly, hypoxia up-regulated Cygb expression in cultured rat kidney fibroblasts. The biological function of Cygb in vivo was evaluated in Cygb-overexpressing transgenic rats. Renal dysfunction and histologic damage after renal I/R were ameliorated (mean [SE] serum urea nitrogen concentration after I/R injury, 260.6 [44.9] mg/dL in wild-type rats versus 101.0 [36.0] mg/dL in transgenic rats; P < 0.05) in association with improvement of oxidative stress. Primary cultured fibroblasts from Cygb transgenic rat kidney were resistant to exogenous oxidant stimuli, and treatment of immortalized kidney fibroblasts with Cygb–small interfering RNA (siRNA) enhanced cellular oxidant stress and subsequently decreased cell viability (cell count ratio after exposure to hydrogen peroxide, 35.9% [1.6%] in control-siRNA-treated cells versus 25.5% [2.0%] in Cygb-siRNA-treated cells; P < 0.05). Further, chemical or mutant disruption of heme in Cygb impaired its antioxidant properties, which suggests that the heme of Cygb per se possesses a radical scavenging function. These findings show for the first time, to our knowledge, that Cygb serves as a defensive mechanism against oxidative stress both in vitro and in vivo.

Globin proteins have a markedly advanced ability to handle oxygen molecules in accordance with surrounding biochemical conditions, and thereby sustain the aerobic metabolism of the respiratory chain. For example, hemoglobin facilitates the transport of oxygen in erythrocytes of the circulatory system,1 and myoglobin facilitates oxygen transport from erythrocytes to mitochondria in cardiac and striated myocytes, thereby maintaining cellular respiration during periods of high physiologic demand.2

Recently, two novel vertebrate globins were discovered, neuroglobin and cytoglobin (Cygb). Kawada et al3 originally characterized Cygb as a 21-kDa heme protein that shows enhanced expression in stellate cells in fibrotic liver as “stellate cell activation-associated protein.” This protein was subsequently identified in the expressed sequence tag databases from zebrafish, mouse, and human, and was renamed Cygb.4,5 Serial studies clarified that Cygb was localized in splanchnic fibroblasts of various organs.3,6 In the normal rat, findings at immunohistochemical analysis suggested that Cygb-positive cells are positive for HSP47, a collagen-specific molecular chaperone of the kidney and intestine, and also for CD73, a marker of renal cortical fibroblast-like cells, in the normal rat kidney interstitium.7

Whereas hemoglobin and myoglobin share the penta-coordinated heme, Cygb and neuroglobin are endowed with hexa-coordinated heme–iron atoms in their ferrous and ferric forms.8 The importance of the biological role of Cygb is emphasized by the high degree of sequence conservation among vertebrate globins, with mouse and human Cygb differing in only 4.7% of amino acids.5 Although various functions have been proposed, including oxygen storage,8 radical scavenging,9–11 collagen synthesis,7,12 tumor suppression,13 and cell respiration,14 these were derived from in vitro studies, and no Cygb gene–manipulated animal experiments have been reported. Therefore, the biological role of Cygb in vivo remains elusive. In addition, the molecular domains and signaling pathways involved with the functions proposed to date remain to be identified.

The kidney is markedly sensitive to changes in oxygen delivery. Although blood flow to the kidney is high, accounting for 20% of cardiac output, the presence of oxygen shunt diffusion between arteries and veins that run in close parallel contact keeps renal tissue oxygen tensions comparatively low. While this sensitivity is useful in facilitating modulation of erythropoietin production in response to changes in oxygen supply, it also renders the kidneys prone to hypoxic injury and subsequent oxidative stress. Inasmuch as globins are essential proteins with the ability to bind oxygen or oxidized compounds such as nitric oxide or carbonic oxide, we hypothesized that Cygb might regulate oxygen or oxidized molecules.

Data from the present study demonstrate the plausibility of this working hypothesis. To determine the functional role of Cygb in the kidney, polyclonal antibodies were raised against synthetic peptides of Cygb. It was then demonstrated that Cygb expression was up-regulated after renal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. Cygb-overexpressing transgenic rats were resistant to I/R injury of the kidney. Although analyses using primary cultured and immortalized kidney fibroblasts supported this biological advantage of Cygb against oxidative stress, these antioxidant effects were not observed when heme function in Cygb was chemically or genetically disrupted.

Materials and Methods

Animal Experiments

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for Animal Experimentation, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Japan. Six-week-old male Wistar rats (Nippon Bio-Supp. Center, Tokyo, Japan) weighing 160 to 200 g were housed. I/R injury to the kidney was induced as previously described,15 and blood was sampled at indicated time points after clamp release. The animals were euthanized, and the kidneys were removed for analysis (n = 6 rats at each time point). Serum creatinine and urea concentrations were determined using the Jaffe reaction (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan), and colorimetrically using the urease-indophenol method (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd). For histologic analysis, tissues were fixed in methyl Carnoy solution, and paraffin-embedded for PAS staining. Semiquantitative analysis of tubulointerstitial injury was performed as previously described.15

Polyclonal Antibody against Rat Cygb

After rabbits were immunized with synthetic rat Cygb peptides conjugated with thyroglobulin, IgG from immune serum was purified. The synthetic polypeptides targeted the amino acid position 66–80, MEDPLEMERSPQLRK-Cys (P1), and polyclonal antibody against synthetic NH2-terminal polypeptides, MEKVPGDMEIERRERNEE-Cys (P2), was produced and affinity-purified as previously described.3 Polystyrene 96-well enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plates (MaxiSorp; Nunc AS, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with the immunogenic polypeptides, and rabbit anti-Cygb IgG was put into each well at various concentrations, followed by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Medical Biological Laboratories Co, Ltd, Nagoya, Japan). Development was performed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Immunoblotting Studies

Kidney cortex was homogenized in sucrose buffer at pH 7.4, followed by centrifugation. Cultured fibroblasts were pelleted, washed in PBS, suspended in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton-X, 10% glycerol, 20 μmol/L HEPES, and 100 mmol/L sodium chloride, and the pellets were cleared by centrifugation. These protein samples were separated using electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, followed by electrotransfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking, the membrane was incubated with the anti-Cygb antibody. Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a loading control. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antibody. Immunoreactive protein was visualized using the chemiluminescence protocol.16

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Three-micrometer sections were stained using the indirect immunoperoxidase method. The first antibody used was affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit anti-Cygb antibody (anti-P1; 1:400). To confirm the findings, rabbit anti-P2 antibody (1:400) was used.3 When indicated, antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides in citrate buffer at pH 6.0 in an autoclave. The number of Cygb-positive cells was counted at ×200 magnification in a blinded manner in 10 tubulointerstitial areas per section randomly selected from each kidney sample.

Double immunostaining of Cygb using antibodies to JG12 (Bender MedSystems, San Bruno, CA) and ED1 (Chemicon International Inc, Temecula, CA) was performed. Alexa546 anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR) and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG (DAKO Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) were used as secondary antibodies. Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA) was also used for nuclear stain to identify macrophages.

4-Hydroxyl-2-nonenal and nitrotyrosine were stained with a corresponding mouse monoclonal antibody (Japan Institute for the Control of Aging, Shizuoka, Japan) and rabbit polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described.17 Quantitative morphometric analysis was performed using commercially available software (Image for Windows; Scion Corp, Frederick, MD). Cells stained with ED1 or proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were counted in 10 randomly selected cortical fields (×200) as previously described.18 All quantifications were performed in a blinded manner.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

After total RNA was isolated with Isogen (Nippon Gene Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), cDNA was synthesized with random primer using a reverse transcription system (ImProm-II; Promega Corp, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One microliter of cDNA was added to SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and subjected to PCR amplification using the iCycler system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, Hercules, CA). Primer sequences were as follows: rat Cygb, 5′-GGTGGAACCTATGTACTTTA-3′, 5′-GGAAGTCATTGGCAAACT-3′; rat p22phox, 5′-GCCATTGCCAGTGTGATCTA-3′, 5′-AATGGGAGTCCACTGCTCAC-3′; rat NOX1, 5′-GGCATCCCTTTACTCTGACCT-3′, 5′-TGCTGCTCGAATATGAATGG-3′19; rat periostin, 5′-TGGTAGCCCAGTTAGGGTTG-3′, 5′-CTGGGGTCAGGTGGTAAAGA-3′20; rat FSP1, 5′-AGGACAGACGAAGCTGCATT-3′, 5′-CTCACAGCCAACATGGAAGA-3′; and rat β-actin as an internal control, 5′-CTTTCTACAATGAGCTGCGTG-3′, 5′-TCATGAGGTAGTCTGTCAGG-3′. PCR was conducted in triplicate for each sample.

Establishment of Cygb-Overexpressing Transgenic Rat

A full-length cDNA fragment of rat Cygb was subcloned into the EcoRI restriction sites of the pCAGGS plasmid.21 After verified by sequencing, plasmids were digested, purified, and microinjected into fertilized eggs of Crlj:Wistar rat, as previously described.22 Three lines of Cygb-overexpressing transgenic rats were engineered, and two were selected. Genomic Southern blot was performed as described elsewhere.23 In brief, 15 μg of genomic DNA obtained from rat tail was digested with EcoRI, underwent electrophoresis on an agarose gel, and transferred onto a nylon membrane for probe hybridization. Hybridization probes were purified and labeled with digoxigenin via amplification of pCAGGS rat Cygb plasmid DNA as template using specific primers: CMV-F1, 5′-GTCGACATTGATTATTGACTAG-3′, and CMV-R1, 5′-CCATAAGGTCATGTACTG-3′. For genotyping, genome DNA was extracted from rat tails using a REDExtract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and subsequently screened using PCR with both primers (Figure 1A): CMV-F1 and CMV-R1 with an amplified 334-bp fragment (30 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds). Primers for the 5′ junction between the vector and inserted Cygb gene were β-gl-3, 5′-CTTCTGGCGTGTGACCGGCG-3′, and rC-1, 5′-CGGTCACATGGCTGTAGATG-3′, with an amplified 622-bp fragment (30 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds). The Cygb-transgenic rats used in this study were offspring of intersibling matings over at least three generations. Heterozygous Cygb-transgenic rats were compared with wild-type littermates.

Figure 1.

Generation and characterization of rabbit polyclonal antibodies against rat Cygb polypeptides. A: Rat Cygb consists of 190 amino acids with a molecular weight of 21,496. Two different antibodies to the corresponding amino acid sequences (full line, P1; dashed line, P2) were used. B: Titration of the polyclonal antibody P1. ELISA of the polyclonal antibody revealed an increase in light absorbance in a dose-dependent manner (full line, closed circle). Isotype IgG control (dashed line, open circle). C: Immunoblot analysis of rat kidney cortex using the antibodies specifically identified Cygb protein.

Isolation of Leukocyte from Rat Peripheral Blood

Peripheral leukocytes were purified as described elsewhere, with modification.24 In brief, blood sampled from the retro-orbital plexus of rats was collected in EDTA-containing tubes, followed by centrifugation and red blood cell lysis with Tris-buffered ammonium chloride to obtain peripheral blood leukocytes.

Cell Culture

Primary cultures of rat kidney fibroblasts were isolated as described elsewhere,25 and maintained in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Nissui Seiyaku Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) and F-12 medium buffered with 25 mmol/L of HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 7.4, supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (SAFH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS), 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 0.01 mmol/L of nonessential amino acids. Immunocytochemistry was performed as previously described.26 In brief, cells were seeded on four-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek; Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY), and fixed with iced acetone-methanol (1:1), followed by indirect immunoperoxidase methods using anti-P1 and antivimentin antibody as primary antibodies. In RT-PCR, primary cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells27 and primary cultured rat mesangial cells28 served as controls. Rat kidney fibroblast cell line NRK49F was obtained from RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan) and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium buffered with 25 mmol/L of HEPES at pH 7.4, supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 0.01 mmol/L of nonessential amino acids. Cells were cultured in humidified 95% air with 5% carbon dioxide at 37°C. Hypoxic conditions were instituted using an Anaerocult A Mini system (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). NRK49F were subjected to hypoxia in a 24-well plate for 20 hours. HEK293T was cultured as previously described.29

siRNA Transfection

NRK49F cells were transfected with control or Cygb-specific siRNA. The rat Cygb siRNA duplex targeted nucleotides 522 to 543 of the Cygb mRNA sequence (NM_130744) and comprised sense (5′-GGUGGAACCUAUGUACUUUAA-3′) and antisense (5′-AAAGUACAUAGGUUCCACCUU-3′). A nontargeting RNA duplex siRNA containing 21 nucleotides was used as control. Cells were passed into 6-well plates and grown to 30% to 50% confluence before transfection. A total of 15 μL of lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen Corp) and 250 pmol of siRNA duplexes were added in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen Corp). At 6 hours after transfection, culture media were replaced with serum-containing media, and cells were subjected to oxidative stress.

Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species and Viability Assay

Fibroblasts were treated with CM-H2DCFDA to detect cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) after transient exposure to hydrogen peroxide using flow cytometric analysis, as previously described.28 The results were consistent with use of hydrogen peroxide at 100 and 1000 μmol/L. For cell viability assay, while cells were incubated in serum-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with hydrogen peroxide at the indicated concentration, cell injury was assessed using the lactic dehydrogenase assay (Kainos Laboratories Inc, Tokyo, Japan), as previously described.30 In addition, cell quantity was estimated using the MTS assay using CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution reagent (Promega Corp, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viability was also quantified using the standard trypan blue exclusion test, with a final dye concentration of 0.4%.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Substitution of histidine for His81 of the rat Cygb protein with a tyrosine residue was conducted using site-directed mutagenesis using a PCR method (30 cycles of PCR consisting of incubation for 10 seconds at 98°C, 5 seconds at 55°C, and 6 minutes at 72°C) with a high-fidelity Taq polymerase (PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase; Takara Bio Inc, Tokyo, Japan) with the rat Cygb gene carried in the pCAGGS plasmid as template. The primers used were sense (5′-GCGGAAATATGCCTGCCGGGTCATGG-3′) and antisense (5′-CAGGCATATTTCCGCAGCTGAGGACT-3′).

Statistical Analysis

All data are given as mean (SE). Statistical analyses were performed using the t test. Nonparametric data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test when appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Expression of Cygb in Kidney Interstitial Fibroblasts

To investigate the expression of Cygb in the kidney, polyclonal antibodies were raised against the middle region of Cygb, MEDPLEMERSPQLRK (P1, Figure 1A). Titration of antibody against P1 at enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay showed a dose-dependent increase in light absorbance (Figure 1B), and immunoblot studies of the kidney cortex with the anti-P1 antibody demonstrated specificity (Figure 1C). Another antibody against synthetic N-terminal polypeptides, MEKVPGDMEIERRERNEE (P2, Figure 1A), also specifically identified rat Cygb protein on immunoblot analysis (Figure 1C).

Immunohistochemical staining with anti-P1 antibody revealed expression of Cygb in the interstitial cells of normal kidney (Figure 2A). High-power magnification views showed both nuclear and cytosolic distribution of Cygb. Although anti-P2 antibody showed essentially the same staining pattern, this antibody stained not only interstitial cells of normal kidney but also glomerular mesangial cells (Figure 2B). Although staining with anti-P1 antibody using the standard technique was negative in glomeruli, antigen retrieval resulted in positive staining in the mesangial area (Figure 2C). An antibody absorption test was performed using anti-P1 antibody preincubated with P1, and confirmed the specificity of the staining (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Immunostaining analysis of Cygb in the normal rat kidney. A: Immunostaining of Cygb with anti-P1 antibody was observed in interstitial fibroblasts of normal rat kidney. Scale bar = 50 μm. Inset, High-power magnification showed diffuse distribution of Cygb in the cell body. Double scale bar = 10 μm. B: Immunostaining of Cygb with anti-P2 antibody was also observed in interstitial fibroblasts and in the mesangial area of normal rat kidney. C: Staining with anti-P1 antibody after antigen retrieval resulted in positive staining in the mesangial area of normal rat kidney. D: Staining for anti-P1 antibody preabsorbed by P1 was negative, confirming its specificity. Scale bar = 50 μm. Images of double immunofluorescence staining with Cygb and cell-specific markers are presented. E: JG12 (vascular endothelial cell) in red and Cygb in green are shown in normal kidney. F: ED1 (macrophage or monocyte) in red, Hoechst in blue, and Cygb in green are shown in the kidney at 48 hours after I/R injury. Arrowheads, macrophages and monocytes. Original magnification of E and F ×200.

To identify interstitial cells expressing Cygb in this model, double staining was performed with cell-specific markers of rat kidney cells. Neither signals of JG12, a marker of rat vascular endothelial cell, nor ED-1, a marker of macrophages and monocytes, co-localized with Cygb (Figure 2, E and F), which suggested that Cygb was expressed by interstitial fibroblasts.

Increase in Cygb-Positive Interstitial Cell Number by I/R Injury

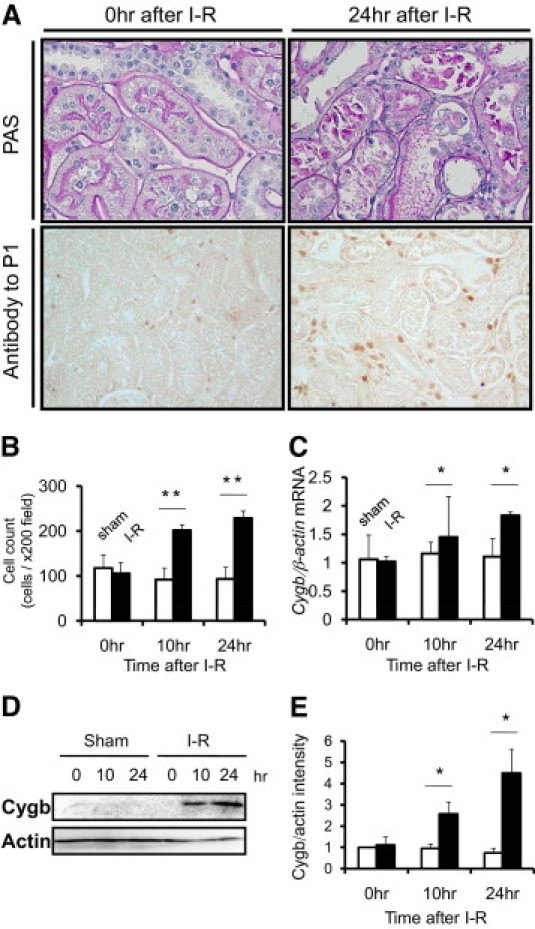

I/R injury of the kidney induced severe tubular damage characterized by tubular dilation, tubular epithelial injury, debris accumulation, and cast formation (Figure 3A). Given the crucial role of oxidative stress in I/R injury, it was speculated that Cygb, as a member of the globin superfamily, may serve a biological role in regulation of oxidized molecules in this model. Immunohistochemical studies using anti-P1 antibody demonstrated that I/R injury of the kidney was associated with up-regulation of Cygb expression in the interstitium. Morphometric analysis demonstrated that the number of Cygb-positive cells was increased at 10 and 24 hours after I/R (Figure 3B). Immunohistochemical studies using anti-P2 antibody also demonstrated up-regulation of Cygb by I/R injury in the interstitium, and quantitative studies with this antibody produced essentially the same result (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Cygb expression in rat kidney cortex after I/R injury. A: PAS staining demonstrated that I/R injury induced severe tubular dilation, tubular epithelial injury, debris accumulation, and cast formation at 24 hours after injury (original magnification ×400). Immunohistochemical analysis using anti-P1 showed up-regulation of Cygb expression in the interstitium at the time-point. (original magnification ×200). B: Quantification of Cygb-positive cells in rat kidney tissue showed temporal increases in Cygb staining after I/R (closed column) in comparison with that after sham operation (open column). C: Cygb mRNA expression level was increased at 10 and 24 hours after I/R injury in a time-dependent manner (closed column), whereas no significant change was observed in sham-operated rats (open column). D: Representative immunoblot of Cygb in kidney cortex tissue after I/R. E: Densitometric analysis of immunoblot demonstrated time-dependent up-regulation of Cygb after I/R injury (closed column) but not after sham operation (open column). *P < 0.05/ **P < 0.01.

To evaluate the temporal profile of Cygb expression in the kidney due to I/R at the mRNA level, real-time quantitative PCR analysis was performed (Figure 3C). At 10 and 24 hours after I/R, Cygb mRNA expression was significantly increased (n = 6). Furthermore, immunoblotting with both anti-P1 and anti-P2 antibody demonstrated that, compared with the sham-operation control, protein expression of Cygb in the cortex was up-regulated at 10 and 24 hours after I/R in a time-dependent manner (Figure 3, D and E).

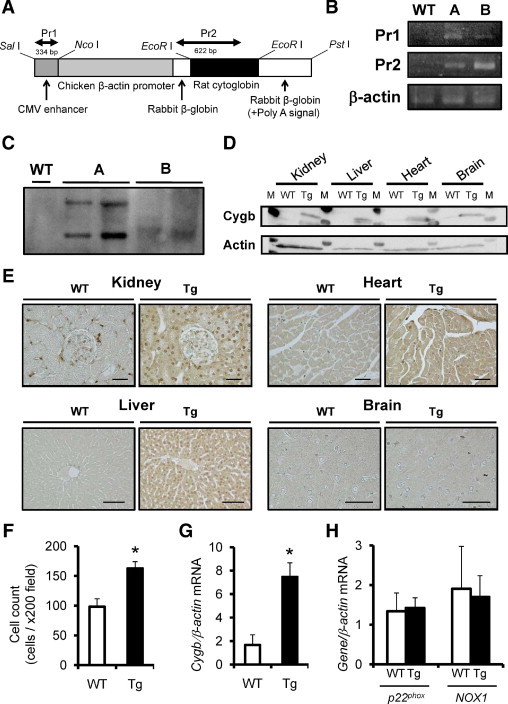

Resistance of Cygb-Transgenic Rats to Kidney I/R Injury

To evaluate the antioxidant function of rat Cygb in vivo, Cygb-overexpressing transgenic rats were established using a construct expressing the rat Cygb gene (Figure 4A). Integration of Cygb was confirmed by genome DNA PCR using two different primers (Figure 4B) and genomic Southern blotting (Figure 4C). The results of the following studies were obtained using line A, but were confirmed in line B, an independent transgenic line. The enhanced expression of Cygb protein in various organs and tissues was confirmed at both immunoblot (Figure 4D) and immunohistochemical (Figure 4E) analysis. In transgenic rat kidney, the number of Cygb-positive interstitial cells was increased (Figure 4F), although it was mildly expressed also in tubular epithelial cells. Transgenic overexpression of Cygb was confirmed in peripheral blood leukocytes (Figure 4G). In addition, whether the transgenic overexpression affected baseline levels of pro-oxidant enzyme expression was examined. However, quantitative PCR found no significant up-regulation or down-regulation in NADPH oxidase components such as NOX1 or p22phox mRNA in the kidney tissue of Cygb-transgenic rats compared with wild-type rats (Figure 4H). Transgenic rat offspring were obtained in an expected mendelian ratio. Baseline phenotypes including growth and external appearance, blood pressure, blood or urine laboratory data, and pathologic analysis of various organs of the transgenic rats did not differ significantly from those of wild-type littermates at age 6 weeks (n = 6, Table 1). The transgenic rats did not develop any pathologic phenotypes at age 6 months (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Establishment and characterization of Cygb-transgenic rats (Tg). A: Cygb transgene construct. Full-length rat Cygb cDNA was subcloned in a vector controlled by the rabbit β-globin gene, including a part of the second intron, the third exon, and the 3′ untranslated region. The positions of primers for PCR analysis are indicated above the construct. B: Identification of rat Cygb transgene by PCR of genomic DNA (line A or B) using primers 1 and 2 (Pr1 and Pr2). C: Southern blot analysis after EcoRI digestion of genomic DNA using probe against transgene sequence. Random integration is demonstrated as distinct position of the bands noted only in mutant lines. D: Overexpression of rat Cygb protein in multiple organs including the kidney, liver, heart, and brain was confirmed using immunoblot analysis. M, molecular weight marker. E: Immunohistochemical analysis also showed enhancement of Cygb protein distribution in these organs of transgenic rats. Scale bar = 50 μm. F: The number of Cygb-positive interstitial cells in the kidney was increased in Cygb-transgenic rats (closed column) compared with wild-type littermates (WT) (open column). G: Overexpression of Cygb mRNA was confirmed in peripheral blood leukocytes of Cygb-transgenic rats (closed column) compared with wild-type littermates (open column). H: Expression of p22phox and NOX1, principal NADPH oxidase components, was examined in the kidney of wild-type rats (open column) and Cygb-transgenic rats (closed column). Transgenic overexpression of Cygb did not affect expression of these enzyme mRNAs. *P < 0.01.

Table 1.

Baseline Phenotype in Cygb-Overexpressing Transgenic Rats⁎

| Variable | Wild-type rats (n = 6) | Transgenic rats (n = 6) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Systolic | 114 (9) | 118 (10) | 0.50 |

| Diastolic | 76 (11) | 76 (9) | 0.95 |

| Serum urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 19.7 (3.4) | 22.7 (3.7) | 0.11 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.47 (0.17) | 0.46 (0.18) | 0.90 |

| Total protein, g/dL | 6.5 (0.2) | 6.6 (0.3) | 0.43 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.2) | 0.40 |

| Urine protein, mg/day | 13 (6) | 13 (5) | 0.84 |

Data are given as mean (SD).

Transgenic overexpression of Cygb in these rats, compared with their wild-type littermates, significantly prevented increase in serum urea nitrogen concentration induced by I/R (n = 6; Figure 5A). Similarly, elevation of serum creatinine levels also differed at 48 hours after I/R injury (Figure 5B), although the difference at 24 hours did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.08). At histopathologic analysis to determine the effects of Cygb overexpression on tubulointerstitial injury in vivo, control animals exhibited severe tubular damage 48 hours after the ischemic insult, characterized by tubular dilation, tubular epithelial injury, debris accumulation, and cast formation. Transgenic overexpression of Cygb improved the tubulointerstitial damage induced by I/R (Figure 5C). These protective effects of Cygb overexpression were confirmed using semiquantitative scoring analysis (Figure 5D). A positive correlation was observed between histologic damage and physiologic parameters in individual rats (serum urea nitrogen, Figure 6E; serum creatinine; Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Attenuation of kidney I/R injury by transgenic overexpression of Cygb in rats. Evaluation of physiologic parameters, serum urea nitrogen (A) and serum creatinine concentration (B), demonstrated that renal dysfunction was milder in Cygb-transgenic rats (Tg) (closed column) at 48 hours after kidney I/R injury compared with that in wild-type rats (WT) (open column). C: Histologic analyses of PAS staining also showed improvement in tissue injury at 48 hours after I/R in Cygb-transgenic rats, including improvements in tubular dilation, epithelial detachment, cast formation, and interstitial cell infiltration. D: Inhibition of histologic damage 48 hours after I/R in transgenic rats (closed column) compared with wild-type littermates (open column) was confirmed using a tubulointerstitial injury scoring system. Confirming validity, tubulointerstitial injury scores showed a significant positive correlation with serum urea nitrogen (E) and serum creatinine (F) concentrations in these rats. Scattergram shows results for transgenic (closed circles) and wild-type (open circles) rats. Original magnification ×400. *P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Oxidative stress and attenuation of kidney I/R injury by transgenic overexpression of Cygb in rats. A: Suppressed deposition of oxidative stress markers 4-HNE in kidney tubulointerstitial area was also observed in Cygb-transgenic rats (Tg). Original magnification ×400. Amelioration of deposition of 4-HNE (B) and nitrotyrosine (C) in transgenic rats (closed column) compared with wild-type rats (WT) (open column) was confirmed at morphometric analysis. D: There were only a few ED1-positive cells before I/R injury in both wild-type and transgenic rats. Although I/R injury increased infiltrating cells, the number of ED1-positive cells was fewer in the Cygb-transgenic rats. Original magnification ×200. E: Quantitative analysis showed the reduced number of ED1-positive cell counts in the Cygb-transgenic rats (closed column) compared with wild-type rats (open column). F: PCNA-positive cell counts were evaluated. At baseline, there were few PCNA-positive cells in wild-type (open column) and Cygb-transgenic (closed column) rat kidney. I/R injury induced proliferation of kidney cells, and the number of PCNA-positive cells was less in Cygb-transgenic rats compared with wild-type rats. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

This improvement in tubulointerstitial injury in Cygb transgenic rats was associated with amelioration of oxidative stress in the kidney. Immunohistologic analysis demonstrated that I/R injury enhanced accumulation of oxidative stress markers such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (Figure 6A) and nitrotyrosine, and quantitative morphometric analysis demonstrated that this increase in staining for these markers was significantly ameliorated by transgenic overexpression of Cygb (Figure 6, B and C). These findings suggested that Cygb, which is up-regulated in the hypoxic kidney, protects against ischemic and oxidative stress in the kidney.

Kidney I/R injury is associated with infiltration of cells such as macrophages and neutrophils. Immunohistochemical analysis with ED1-antibody demonstrated that transgenic overexpression of Cygb did not increase the number of residential macrophages before I/R injury (Figure 6D). It was observed that I/R injury elevated the number of ED1-postive cells in both wild-type and Cygb-transgenic rats. However, quantitative analysis demonstrated fewer ED1-positive cells in the kidney of transgenic rats compared with wild-type rats (Figure 6E).

Repair process after acute ischemic kidney injury requires proliferation of tubular cells; thus, whether Cygb overexpression accelerated tubular cell proliferation was tested. The number of PCNA-positive tubular cells was counted in both Cygb-transgenic and wild-type rats before and after I/R injury. Cygb overexpression did not accelerate tubular cell proliferation under basal conditions. The number of PCNA-positive cells was smaller in transgenic rats than in wild-type rats after I/R injury (Figure 6F).

Resistance of Primary Cultures of Cygb-Transgenic Rat Kidney Fibroblast to Oxidative Stress

To investigate whether interstitial fibroblasts have a protective role against oxidative stress associated with renal I/R injury, primary cultures of rat kidney fibroblasts were isolated, and the number of surviving cells following exposure to hydrogen peroxide was evaluated. When grown in thin mass cultures, these cells are stellate or spindle or angular shaped, mostly with processes. Immunocytochemical analysis demonstrated expression of not alpha smooth muscle actin but vimentin in these primary cultured cells, indicating the fibroblast phenotype (Figure 7A). Periostin, another fibroblast marker, mRNA is also expressed in these cells, but not in primary cultures of rat vascular smooth muscle cells or rat mesangial cells (data not shown). In cultured cells from transgenic rats, immunostaining of Cygb was strongly positive compared with those from wild-type rats (Figure 7B). Immunoblot analysis also demonstrated enhanced expression of Cygb in transgenic rat cells (Figure 7C). A decrease in oxygen tension led to up-regulation of Cygb mRNA in cultured fibroblasts of wild-type rats compared with cells under normoxic culture conditions (mean [SD], 27.4 [10.5]-fold versus 1.00 [0.50]-fold; P < 0.05), demonstrating oxygen-dependent regulation of Cygb expression. Furthermore, lactodehydrogenase release assay of Cygb-transgenic and wild-type kidney fibroblasts exposed to hydrogen peroxide (n = 6) revealed that fibroblasts from Cygb-transgenic rats exhibited less damage than cells from wild-type littermates (Figure 7D). MTS assay (n = 8) also revealed that the number of living fibroblasts from Cygb-transgenic rats was larger after addition of hydrogen peroxide (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

Oxidative stress and overexpression or knockdown of Cygb expression in rat kidney fibroblasts. A: Immunocytochemical analysis showed vimentin expression in primary cultured fibroblasts from rat kidney. Original magnification ×1000. Expression of Cygb was higher in primary cultures of kidney fibroblasts from Cygb-transgenic rats than from wild-type rats, as estimated by immunocytochemical (B) and immunoblot (C) analyses. D: Cell damage under 24-hour exposure with 100 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide as oxidant stress inducer was evaluated using the lactic dehydrogenase assay. The enzyme release ratio was suppressed in Cygb-transgenic rat kidney fibroblasts (closed column) compared with wild-type fibroblasts (open column). E: During the time course, Cygb-transgenic rat kidney fibroblasts (full line) showed better survival than did wild-type fibroblasts (dashed line) under exposure of 50 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide, as demonstrated using the MTS assay. F: Cygb-siRNA decreased Cygb protein expression at 24 hours after transfection in NRK49F cells. G: Flow cytometric analysis to detect radical fluorescence in rat kidney fibroblasts treated with hydrogen peroxide showed that hydrogen peroxide increased cellular ROS production in Cygb-siRNA-treated fibroblasts. The ROS-positive cell number in the Cygb-siRNA-treated fibroblasts (closed column) was larger than that in the control-siRNA-treated fibroblasts (open column). H: Viability of cultured fibroblasts treated with Cygb-siRNA when exposed to 300 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide for 24 hours as evaluated. NRK49F cells treated with Cygb-siRNA (closed column) were more susceptible to extracellular oxidative stimuli than those treated with control siRNA (open column). NS, no significant difference. *P < 0.05.

Vulnerability to Oxidative Stress by Cygb-Knockdown in Kidney Fibroblasts

To clarify the functional role of Cygb in kidney fibroblasts, the rat kidney fibroblast cell line NRK49F was studied. A cell line was used rather than primary cultured cells because of the greater difficulty of introducing transgenes or siRNA into the primary cultured cells. Similar to the results of primary cultured cell studies, hypoxia induced up-regulation of Cygb mRNA expression compared with normoxic culture conditions in this cell line (2.32 [0.39]-fold versus 1.00 [0.21]-fold; P < 0.05). Next, NRK49F cells were treated with siRNA specific to rat Cygb, and siRNA significantly (P < 0.05) reduced mRNA levels of Cygb at 24 hours after transfection, with a suppression rate of approximately 50%. Knockdown of Cygb by siRNA transfection in the fibroblasts was also confirmed at immunoblot analysis (Figure 7F). Measurement of intracellular ROS using a fluorescence probe revealed that Cygb-knockdown fibroblasts held a greater amount of ROS when exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the number of ROS-positive cells was significantly larger when treated with siRNA against Cygb (n = 6; Figure 7G). Insofar as the biological consequences of increased oxidative stress due to suppression of Cygb, cultured fibroblasts treated with siRNA against Cygb demonstrated less viability against extracellular oxidant insult with hydrogen peroxide, as measured using the MTS assay (n = 8), whereas treatment with Cygb-siRNA per se did not alter cell viability in cells without oxidative stress (Figure 7H). Aggravation of cellular damage via knockdown of Cygb was confirmed using other assays under the same conditions, namely, the lactic dehydrogenase assay (control-siRNA cells, 65.3% [2.3%] vs Cygb-siRNA-treated cells, 71.1% [1.5%]; P < 0.05; n = 6), and the trypan blue exclusion test (6.2% [0.9%] versus 8.9% [0.7%]; P < 0.05; n = 6) revealed that cells treated with Cygb-siRNA were more vulnerable to oxidative stress.

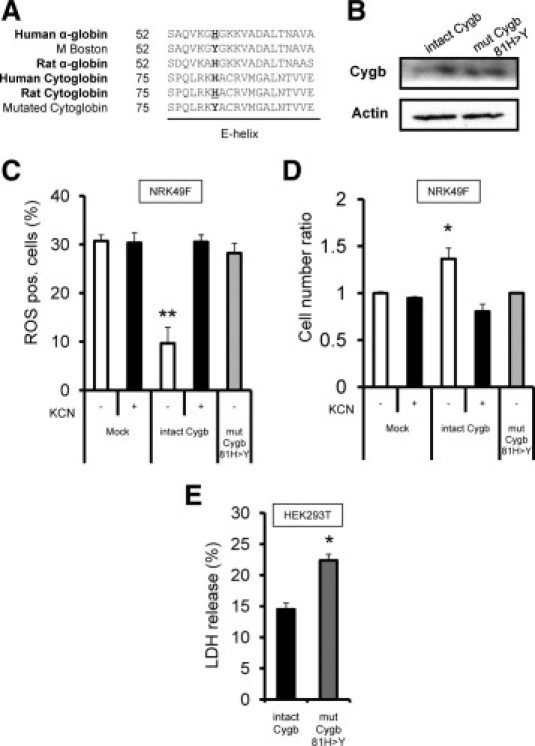

Effect of Disruption of Heme in Cygb on Antioxidant Properties

To investigate what mediates the self-protective role of Cygb against oxidative stress, expression levels of principal antioxidant enzymes were evaluated. However, no difference was observed in mRNA expression levels of heme oxygenase-1, catalase, and superoxide dismutase types 1 and 2 between kidney cortex samples from Cygb-transgenic rats and wild-type littermates. Also observed was a lack of effect of Cygb-gene silencing on expression of these antioxidant enzymes in cultured fibroblasts. It was, therefore, unlikely that the antioxidative effect of Cygb was secondary to the regulation of expression of other antioxidant enzymes, leading to speculation that Cygb per se possesses a radical scavenging function.

It was hypothesized that the heme component of Cygb is the main contributor to radical scavenging. To support this hypothesis, it was examined whether the disturbance of heme function might lead to down-regulation of the antioxidant properties of Cygb. Whereas cultured fibroblast NRK49F transfected with a plasmid vector expressing rat Cygb demonstrated a decrease in intracellular ROS under oxidative stress, the addition of heme poison potassium cyanide at 1 mmol/L blunted this important self-protective property (n = 6; Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Decrease in protective properties of Cygb chemical or genetic disruption of heme protein in Cygb. A: For mutagenesis of rat Cygb molecule unable to bind ligands, gene mutation of the hemoglobin α-subunit responsible for human methemoglobinemia was used. A common mutated designation, also called M Boston, naturally occurs as 58His>Tyr in the E helix of human α-globin protein, which corresponds to 81His>Tyr in rat Cygb. B: Plasmid vector expressing intact form of Cygb protein or 58His>Tyr mutated Cygb protein was transfected into NRK49F cells. Immunoblotting analysis with anti-P1 antibody showed equal levels of expression of intact and mutant forms of Cygb for reasonable comparison in transient transfection studies. C: While fibroblasts expressing an intact form of rat Cygb demonstrated lower levels of intracellular ROS under exposure to hydrogen peroxide in comparison with fibroblasts transfected with control vectors (open column), fibroblasts expressing mutated rat Cygb failed to reduce intracellular ROS levels (shaded column). Potassium cyanide added as heme poison to the culture media inhibited ROS reduction in cells expressing intact Cygb but did not affect ROS levels in control cells (closed column). D: The MTS cell counting method demonstrated that the cell viability of intact Cygb-transfected fibroblasts after 6-hour exposure to 1 mmol/L of hydrogen peroxide (open column) was greater than that of mutated Cygb-transfected fibroblasts (shaded column) or of fibroblasts cultured with potassium cyanide (closed column). E: Antioxidant property of Cygb was confirmed in HEK293T cells. The lactic dehydrogenase release assays demonstrated that HEK293T cells expressing intact Cygb protein (closed column) were resistant to 24-hour exposure to 50 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide compared with cells expressing mutated Cygb (shaded column). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

Further, mutant cells were engineered with impaired ability to bind ligands at the heme of Cygb. Design of these mutants was assisted by reference to the pathogenesis of human methemoglobinemia, in which the genetic mutation of hemoglobin results in inability to bind oxygen molecules and severe systemic cyanosis. The distal histidine is a classic mutation in hereditary methemoglobinemia, and based on a shared structural homology between hemoglobin and Cygb (Figure 8A), the distal histidine (His81 in the rat Cygb protein) was substituted with a tyrosine residue. Immunoblotting analysis confirmed equal levels of expression of intact and mutant forms of Cygb for reasonable comparison in the transient transfection studies of NRK49F fibroblasts (Figure 8B). Kidney fibroblasts expressing mutated Cygb demonstrated decreased ROS scavenging activity compared with cells expressing wild-type Cygb. In addition, cultured fibroblasts expressing mutated Cygb exhibited less viability to extracellular oxidant insult by exposure to hydrogen peroxide, as measured using the MTS assay (n = 8; Figure 8D).

Whether Cygb-overexpression had an antioxidant role in the kidney cells with epithelioid nature as well as in interstitial cells was tested. The lactic dehydrogenase release assays demonstrated that HEK293T cells that overexpressed intact Cygb protein were damaged less than cells that overexpressed mutated Cygb protein when treated with hydrogen peroxide (n = 6; Figure 8E).

Discussion

Cygb is a recently discovered intracellular globin that exists in multiple organs in mammals. In the present study, immunostaining was performed to demonstrate that this protein is expressed in interstitial cells of rat kidney, with two different antibodies against independent peptide sequences exhibiting essentially the same staining pattern in the interstitium. The localization of Cygb was consistent with previous reports that identified Cygb in splanchnic fibroblasts of various organs.6,7 Given the status of fibroblasts as one of the most important and episodically active cell types in the kidney, providing delicate collagenous matrices and remodeling of the interstitium, this localization may suggest a crucial role for Cygb in the pathogenesis of kidney injury.31,32

An antibody-dependent difference was observed in the Cygb staining pattern in the glomeruli; whereas one antibody demonstrated positive staining in the mesangial area, a second antibody demonstrated positive staining only after antigen retrieval in the mesangial area. Whether this mesangial area staining was due to changes in the antigenicity of Cygb in a specific cell type or to cross-reactivity with unknown molecules remains to be elucidated. The present study focused on Cygb expression in the interstitium on the basis that ischemic injury of the kidney affects primarily the tubulointerstitial region.

A substantial increase was demonstrated in the number of Cygb-positive cells in the tubulointerstitial compartment after I/R, which suggested that Cygb may be induced against acute hypoxic damage. A decrease in oxygen tension was a stimulus to increase Cygb expression in cultured kidney fibroblasts. Cygb can be up-regulated in other tissues and cells under hypoxic conditions.6,33,34 Induction of Cygb via ischemia might be explained by a hypoxia-inducible factor–dependent mechanism. The promoter region of Cygb contains multiple conserved hypoxia-response elements.35 Further, up-regulation of Cygb by hypoxia was affected in hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (+/−) knockout mice.33 Strong induction of Cygb protein at 24 hours after the kidney ischemic injury was demonstrated, compared with relatively mild up-regulation of Cygb mRNA. Except for transcriptional regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor,35 there is little knowledge about the synthesis or degeneration processes of Cygb protein, and some inhibitory mechanism in degeneration of this protein might be involved in induction of Cygb protein in vivo.

The biological role of Cygb has been the subject of intense study. Cygb shows the same order of oxygen affinity as does myoglobin, which suggests that it may facilitate oxygen diffusion into the mitochondrial respiratory chain.4 On this basis, up-regulation of Cygb in the hypoxic kidney may be an adaptive response to increase the efficiency of mitochondrial respiration under oxygen deprivation states. In addition, oxidative stress likely mediates many of the deleterious effects of I/R injury,36,37 with the tubulointerstitium as the main target.38,39 Recent studies suggest that Cygb may sense oxygen concentration and act as a regulatory protein that protects cells from ROS.9 Therefore, it was hypothesized that up-regulation of Cygb protein may have a protective role against oxidative stress in the hypoxic kidney.

To test this hypothesis, novel transgenic rats overexpressing Cygb constitutively were established. When I/R injury of the kidney was induced in experimental rats, overexpression of Cygb was protective. This protective role was confirmed in two independent transgenic rat lines. These genetically engineered animals enabled us to identify for the first time a biological function of Cygb in vivo, that is, antioxidative stress.

Because a ubiquitous promoter was used to establish the transgenic animals, overexpression of Cygb was observed in tubules in addition to fibroblasts. The tubulointerstitial compartment is the major target of I/R injury in the kidney, and it is likely that Cygb in tubular epithelial cells40 and circulating leukocytes such as macrophages and neutrophils41 had a protective role in the transgenic animals. Overexpression of Cygb was confirmed also in peripheral leukocytes isolated from Cygb-transgenic rats, and HEK293T cells overexpressing Cygb demonstrated an antioxidant effect. In contrast, Cygb did not promote cell proliferation, although tubular proliferation is thought essential for kidney repair. It is likely that the fewer numbers of infiltrating macrophages and monocytes, and proliferating tubular cells in Cygb-transgenic rats reflect amelioration of I/R injury via Cygb overexpression.

A biological role of interstitial fibroblasts in this acute model remains to be defined. In the early days after unilateral renal I/R injury, nevertheless, active cell proliferation is observed in the interstitial area and the tubular compartment.42 In addition, there is evidence that post-ischemic interstitial cells are regulated independently by mediators such as growth factors.43 Interstitial fibroblasts respond shortly to acute ischemic insult, and could contribute to interstitial pathology during an acute phase.

To investigate the antioxidative stress function of Cygb at the cellular level, primary culture of rat kidney fibroblast isolated from Cygb-transgenic and wild-type rats and immortalized rat kidney fibroblast cell lines transfected with Cygb-siRNA was used, followed by estimation of the viability of cultured fibroblasts exposed to hydrogen peroxide as a source of oxidative stress. In addition to vimentin and periostin,20 expression of FSP1 was observed in the primary cultures. However, also detected was expression of FSP1 in rat cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Thus, specificity of FSP1 expression in rats may not be so high as it is in mice, which is consistent with a previous report.44 Concentrations of hydrogen peroxide were determined depending on cell type and time course of the studies. Three different assays showed that knockdown of Cygb in immortalized kidney fibroblasts decreased cell viability on exposure to hydrogen peroxide. The protective role of Cygb against oxidative stress was confirmed in studies using primary cultured kidney fibroblasts that overexpressed Cygb. It is likely that the enhanced vulnerability by Cygb knockdown was due to increased intracellular ROS, as demonstrated by analysis using CM-H2DCFDA fluorescence. Recent studies of neuronal cancer cells support the finding of the antioxidative stress effects of Cygb.10,11 In addition to Cygb, recent studies reported that hemoglobin28 and myoglobin45 also scavenge radicals, which emphasizes a role for globin proteins as antioxidants. Collectively, these in vitro studies suggest a novel antioxidative role for globins in addition to their known conventional facilitation of oxygen transport, and support the finding that Cygb serves as a defensive mechanism against oxidative stress.

Heme is a porphyrin molecule with diverse biological functions including transportation of diatomic gases, chemical catalysis, and electron transfer. It is shared by all members of the globin superfamily of proteins. In the present study, chemical poisoning and His81 mutant-oriented disruption of heme attenuated the radical scavenging properties of Cygb, indicating that heme is responsible for the cytoprotective role of Cygb. Because Cygb and neuroglobin are the first examples of hexa-coordinated globins in which the His residue at the sixth position of the heme iron is an endogenous ligand in both the ferric and ferrous forms, clarification of their biological activity will require different approaches to those used for penta-coordinated globins such as hemoglobin and myoglobin. In neuroglobin, mutation of His to Leu in the E helix increases the ligand-binding constants, indicating that the endogenous ligand can be replaced by external ligands such as oxygen and carbonic monoxide.46 Based on their spectroscopic analysis, Sawai et al47 also suggested that His residue is responsible for the globin conformer structure and heme-ligand binding. These findings support experiments demonstrating that the heme domain is an important contributor to radical scavenging. This effect may be confirmed in vivo by inducing kidney I/R in rats overexpressing mutant Cygb.

In conclusion, Cygb, a newly identified member of the globin family, is expressed in the interstitial fibroblasts of the kidney and is up-regulated by I/R injury. Using both transgenic rats and cultured kidney fibroblasts, it was demonstrated for the first time that Cygb expression confers cellular protection via an antioxidant mechanism and that heme in Cygb is crucial because of its antioxidative ability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ryuichi Nishinakamura (Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan) for valuable advice and technical support.

Footnotes

Supported by Research Fellowships for Young Scientists 09J07041 (H.N.), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 19390228 and 2139036 (M.N.) and 19590939 (R.I.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Ninth Japanese Society for Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Research in Renal Failure (H.N.), and an Ishidsu Shun Memorial Scholarship (I.M.).

Current address of K.Y., PhoenixBio Co., Ltd., Hiroshima, Japan.

References

- 1.Hardison R.C. A brief history of hemoglobins: plant, animal, protist, and bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittenberg B.A., Wittenberg J.B. Transport of oxygen in muscle. Annu Rev Physiol. 1989;51:857–878. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.004233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawada N., Kristensen D.B., Asahina K., Nakatani K., Minamiyama Y., Seki S., Yoshizato K. Characterization of a stellate cell activation-associated protein (STAP) with peroxidase activity found in rat hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25318–25323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trent J.T., III, Hargrove M.S. A ubiquitously expressed human hexacoordinate hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19538–19545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burmester T., Ebner B., Weich B., Hankeln T. Cytoglobin: a novel globin type ubiquitously expressed in vertebrate tissues. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:416–421. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt M., Gerlach F., Avivi A., Laufs T., Wystub S., Simpson J.C., Nevo E., Saaler-Reinhardt S., Reuss S., Hankeln T., Burmester T. Cytoglobin is a respiratory protein in connective tissue and neurons, which is up-regulated by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8063–8069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakatani K., Okuyama H., Shimahara Y., Saeki S., Kim D.H., Nakajima Y., Seki S., Kawada N., Yoshizato K. Cytoglobin/STAP, its unique localization in splanchnic fibroblast-like cells and function in organ fibrogenesis. Lab Invest. 2004;84:91–101. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pesce A., Bolognesi M., Bocedi A., Ascenzi P., Dewilde S., Moens L., Hankeln T., Burmester T. Neuroglobin and cytoglobin: fresh blood for the vertebrate globin family. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1146–1151. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mammen P.P., Shelton J.M., Ye Q., Kanatous S.B., McGrath A.J., Richardson J.A., Garry D.J. Cytoglobin is a stress-responsive hemoprotein expressed in the developing and adult brain. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1349–1361. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7008.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fordel E., Thijs L., Martinet W., Lenjou M., Laufs T., Van Bockstaele D., Moens L., Dewilde S. Neuroglobin and cytoglobin overexpression protects human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells against oxidative stress–induced cell death. Neurosci Lett. 2006;410:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D., Chen X.Q., Li W.J., Yang Y.H., Wang J.Z., Yu A.C. Cytoglobin up-regulated by hydrogen peroxide plays a protective role in oxidative stress. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1375–1380. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tateaki Y., Ogawa T., Kawada N., Kohashi T., Arihiro K., Tateno C., Obara M., Yoshizato K. Typing of hepatic nonparenchymal cells using fibulin-2 and cytoglobin/STAP as liver fibrogenesis-related markers. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0666-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shivapurkar N., Stastny V., Okumura N., Girard L., Xie Y., Prinsen C., Thunnissen F.B., Wistuba I.I., Czerniak B., Frenkel E., Roth J.A., Liloglou T., Xinarianos G., Field J.K., Minna J.D., Gazdar A.F. Cytoglobin, the newest member of the globin family, functions as a tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7448–7456. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halligan K.E., Jourd'heuil F.L., Jourd'heuil D. Cytoglobin is expressed in the vasculature and regulates cell respiration and proliferation via nitric oxide dioxygenation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8539–8547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808231200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto M., Makino Y., Tanaka T., Tanaka H., Ishizaka N., Noiri E., Fujita T., Nangaku M. Induction of renoprotective gene expression by cobalt ameliorates ischemic injury of the kidney in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1825–1832. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000074239.22357.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami T., Inagi R., Wada T., Tanaka T., Fujita T., Nangaku M. Indoxyl sulfate inhibits proliferation of human proximal tubular cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F568-–F576. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00659.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Son D., Kojima I., Inagi R., Matsumoto M., Fujita T., Nangaku M. Chronic hypoxia aggravates renal injury via suppression of Cu/Zn-SOD: a proteomic analysis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F62-–F72. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00113.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumagai T., Nangaku M., Kojima I., Nagai R., Ingelfinger J.R., Miyata T., Fujita T., Inagi R. Glyoxalase I overexpression ameliorates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F912-–F921. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90575.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanna A.K., Pieper G.M. NADPH oxidase subunits (NOX-1, p22phox. Rac-1) and tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity in a rat renal transplant model. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:376–385. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda N., Manabe I., Uchino Y., Eguchi K., Matsumoto S., Nishimura S., Shindo T., Sano M., Otsu K., Snider P., Conway S., Nagai R. Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:254–265. doi: 10.1172/JCI40295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyata T., Inagi R., Nangaku M., Imasawa T., Sato M., Izuhara Y., Suzuki D., Yoshino A., Onogi H., Kimura M., Sugiyama S., Kurokawa K. Overexpression of the serpin megsin induces progressive mesangial cell proliferation and expansion. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:585–593. doi: 10.1172/JCI14336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue S., Inoue M., Fujimura S., Nishinakamura R. A mouse line expressing Sall1-driven inducible Cre recombinase in the kidney mesenchyme. Genesis. 2010;48:207–212. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullere X., Lauterbach M., Tsuboi N., Mayadas T.N. Neutrophil-selective CD18 silencing using RNA interference in vivo. Blood. 2008;111:3591–3598. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommer M., Schaller R., Funfstuck R., Bohle A., Bohmer F.D., Muller G.A., Stein G. Abnormal growth and clonal proliferation of fibroblasts in an animal model of unilateral ureteral obstruction. Nephron. 1999;82:39–50. doi: 10.1159/000045366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mimura I., Nangaku M., Nishi H., Inagi R., Tanaka T., Fujita T. Cytoglobin, a novel globin, plays an anti-fibrotic role in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F1120–F1133. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joki N., Kaname S., Hirakata M., Hori Y., Yamaguchi T., Fujita T., Katoh T., Kurokawa K. Tyrosine-kinase dependent TGF-beta and extracellular matrix expression by mechanical stretch in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertens Res. 2000;23:91–99. doi: 10.1291/hypres.23.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishi H., Inagi R., Kato H., Tanemoto M., Kojima I., Son D., Fujita T., Nangaku M. Hemoglobin is expressed by mesangial cells and reduces oxidant stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1500–1508. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kojima I., Tanaka T., Inagi R., Nishi H., Aburatani H., Kato H., Miyata T., Fujita T., Nangaku M. Metallothionein is upregulated by hypoxia and stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2009;75:268–277. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nangaku M., Quigg R.J., Shankland S.J., Okada N., Johnson R.J., Couser W.G. Overexpression of Crry protects mesangial cells from complement-mediated injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:223–233. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V82223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris R.C., Neilson E.G. Toward a unified theory of renal progression. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:365–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neilson E.G. Mechanisms of disease: fibroblasts; a new look at an old problem. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fordel E., Geuens E., Dewilde S., Rottiers P., Carmeliet P., Grooten J., Moens L. Cytoglobin expression is upregulated in all tissues upon hypoxia: an in vitro and in vivo study by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fordel E., Thijs L., Moens L., Dewilde S. Neuroglobin and cytoglobin expression in mice: evidence for a correlation with reactive oxygen species scavenging. Febs J. 2007;274:1312–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wystub S., Ebner B., Fuchs C., Weich B., Burmester T., Hankeln T. Interspecies comparison of neuroglobin, cytoglobin and myoglobin: sequence evolution and candidate regulatory elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;105:65–78. doi: 10.1159/000078011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C., Jackson R.M. Reactive species mechanisms of cellular hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C227–C241. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00112.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kojima I., Tanaka T., Inagi R., Kato H., Yamashita T., Sakiyama A., Ohneda O., Takeda N., Sata M., Miyata T., Fujita T., Nangaku M. Protective role of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha against ischemic damage and oxidative stress in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1218–1226. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brezis M., Rosen S. Hypoxia of the renal medulla: its implications for disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:647–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nangaku M. Chronic hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:17–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ichimura T., Asseldonk E.J., Humphreys B.D., Gunaratnam L., Duffield J.S., Bonventre J.V. Kidney injury molecule-1 is a phosphatidylserine receptor that confers a phagocytic phenotype on epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1657–1668. doi: 10.1172/JCI34487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayadas T.N., Rosetti F., Ernandez T., Sethi S. Neutrophils: game changers in glomerulonephritis. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forbes J.M., Hewitson T.D., Becker G.J., Jones C.L. Ischemic acute renal failure: long-term histology of cell and matrix changes in the rat. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2375–2385. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spurgeon K.R., Donohoe D.L., Basile D.P. Transforming growth factor-beta in acute renal failure: receptor expression, effects on proliferation, cellularity, and vascularization after recovery from injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F568–F577. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00330.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies M., Harris S., Rudland P., Barraclough R. Expression of the rat: S-100-related, calcium-binding protein gene, p9Ka, in transgenic mice demonstrates different patterns of expression between these two species. DNA Cell Biol. 1995;14:825–832. doi: 10.1089/dna.1995.14.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flogel U., Godecke A., Klotz L.O., Schrader J. Role of myoglobin in the antioxidant defense of the heart. FASEB J. 2004;18:1156–1158. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1382fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dewilde S., Kiger L., Burmester T., Hankeln T., Baudin-Creuza V., Aerts T., Marden M.C., Caubergs R., Moens L. Biochemical characterization and ligand binding properties of neuroglobin, a novel member of the globin family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38949–38955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawai H., Makino M., Mizutani Y., Ohta T., Sugimoto H., Uno T., Kawada N., Yoshizato K., Kitagawa T., Shiro Y. Structural characterization of the proximal and distal histidine environment of cytoglobin and neuroglobin. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13257–13265. doi: 10.1021/bi050997o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]