Abstract

In the past decade, lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) has emerged as a significant component of cell death signaling. The mechanisms by which lysosomal stability is regulated are not yet fully understood, but changes in the lysosomal membrane lipid composition have been suggested to be involved. Our aim was to investigate the importance of cholesterol in the regulation of lysosomal membrane permeability and its potential impact on apoptosis. Treatment of normal human fibroblasts with U18666A, an amphiphilic drug that inhibits cholesterol transport and causes accumulation of cholesterol in lysosomes, rescued cells from lysosome-dependent cell death induced by the lysosomotropic detergent O-methyl-serine dodecylamide hydrochloride (MSDH), staurosporine (STS), or cisplatin. LMP was decreased by pretreating cells with U18666A, and there was a linear relationship between the cholesterol content of lysosomes and their resistance to permeabilization induced by MSDH. U18666A did not induce changes in expression or localization of 70-kDa heat shock proteins (Hsp70) or antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins known to protect the lysosomal membrane. Induction of autophagy also was excluded as a contributor to the protective mechanism. By using Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with lysosomal cholesterol overload due to a mutation in the cholesterol transporting protein Niemann-Pick type C1 (NPC1), the relationship between lysosomal cholesterol accumulation and protection from lysosome-dependent cell death was confirmed. Cholesterol accumulation in lysosomes attenuates apoptosis by increasing lysosomal membrane stability.

Lysosomes are organelles involved in macromolecule turnover and, consequently, contain numerous hydrolytic enzymes, including the cathepsin family of proteases. Cathepsins are synthesized as inactive proenzymes, which are transported to the lysosomes and converted to active proteases inside these organelles. In addition to their involvement in protein degradation, cathepsins also have several other functions, including promotion of apoptotic cell death.1 Release from the lysosomes into the cytosol is critical for participation of cathepsins in apoptosis. Lysosomotropic detergents, which selectively target the lysosomal membrane, are compounds that remain predominantly unprotonated and inert in the cytosol, but they become protonated, accumulate, and acquire detergent properties in the acidic interior of lysosomes.2 Low concentrations of lysosomotropic detergents cause a limited translocation of lysosomal contents leading to apoptosis, whereas higher concentrations result in massive lysosomal release and subsequent necrotic cell death.3 Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) and subsequent release of cathepsins is an early event during apoptosis induced by a number of stimuli, such as oxidative stress, death receptor ligation, and DNA-damaging drugs.1 Because the presence of cathepsins in the cytosol is sufficient to trigger apoptosis,4 the permeability of the lysosomal membrane is tightly regulated to prevent accidental cell death. Increasing evidence suggests that several proteins, including antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins and heat shock proteins (Hsps), act as safeguards of lysosomal membrane integrity.5

As an essential component of cellular membranes, cholesterol is critical for many cellular functions, including signal transduction and membrane trafficking. The majority of cellular cholesterol normally resides in the plasma membrane.6 However, cells from patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) are notable exceptions, in that a large amount of cholesterol is found in lysosomes.7 NPC is an inherited lysosomal storage disorder that is characterized by a failure in cholesterol trafficking that leads to accumulation of unesterified cholesterol and sphingolipids in the endo-lysosomal system.8 This disease is caused by mutations in the genes coding for the proteins NPC1 and NPC2, which are crucial for transport of cholesterol from the lysosomal compartment to the endoplasmic reticulum for esterification and redistribution to other cellular compartments.6 U18666A [3-β-(2-[diethylamino]ethoxy)-androst-5-en-17-one, monohydrochloride] is an amphiphilic drug known to inhibit cholesterol transport8 and, therefore, commonly used to mimic NPC defects in cell culture models. U18666A treatment results in lysosomal cholesterol accumulation,8 which is associated with induction of apoptosis in the primary cortical neurons of mice.9 Cholesterol reinforces lysosomal membrane stability in cell-free experiments. Addition of cholesterol to isolated lysosomes reduces permeability,10 whereas a reduced lysosomal membrane cholesterol level is associated with increased permeability to protons and potassium ions that, in turn, causes an osmotic imbalance and destabilization of the lysosomal membrane.11 The aim of this study was to investigate whether lysosomal accumulation of cholesterol alters lysosomal membrane permeability and cellular sensitivity to induction of apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-cathepsin D (01-12-030104; Athens Research and Technology, Athens, GA); mouse anti-LBPA (anti–lysobisphosphatidic acid; Z-SLBPA; Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT); mouse anti-LAMP-2 (anti–lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2; 9840-01; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL); rabbit anti-LC3B (NB600-1384; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO); goat anti-LDH (anti–polyclonal lactate dehydrogenase; 20-LG22; Fitzgerald Industries International, Concord, MA); mouse anti-GAPDH (anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GTX78213, GeneTex, Irvine, CA); and rabbit anti–Mcl-1(sc-958), rabbit anti–Bcl-XL (sc-7195), mouse anti–Bcl-2 (sc-509), and mouse anti-Hsp70 (sc-24), all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cells and Culture Conditions

Human foreskin fibroblasts (AG01518; passages 12–24; Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Camden, NJ) were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium supplemented with 2 mmol/L glutamine, 50 IU/ml penicillin-G, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (all from GIBCO, Paisley, UK). Cells were incubated in humidified air with 5% CO2 at 37°C and were subcultured once a week. Before experiments, cells were trypsinized and seeded to reach 80% confluence at apoptosis induction. Cells were pretreated with 0.5 μg/ml U18666A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in complete cell culture medium for the indicated durations. For selected experiments, 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC; 1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) was added simultaneously with U18666A. At the times indicated, cells were pretreated with 3-methyladenine (3-MA; 5 mmol/L, 1 hour; Sigma-Aldrich). Apoptosis was induced by exposing cells to the lysosomotropic detergent O-methyl-serine dodecylamide hydrochloride [MSDH; 15 μmol/L; kindly provided by Gene M. Dubowchik (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, CT)], the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (STS; 0.1 μmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich), or the anticancer drug cisplatin (40 μg/ml; Meda, Solna, Sweden). Apoptosis-inducing agents were added in serum-free medium and, for pretreated cultures, in the presence of U18666A.

Chinese hamster ovary 2-2 (CHO 2-2) cells are mutated from CHO-K112 and represent a classic NPC phenotype.13 The Npc1 gene of the CHO 2-2 cells contains an insertion resulting in a frame shift and early termination of NPC1 translation, creating a nonfunctional protein.14 CHO cells were cultured in 1:1 Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture supplemented with 2 mmol/L glutamine, 50 IU/ml penicillin-G, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (all from GIBCO). Cells were incubated in humidified air with 5% CO2 at 37°C and were subcultured twice a week. Before experiments, CHO-K1 and CHO 2-2 were trypsinized and seeded 1 day before experiments to reach 80% confluence at the time of exposure to STS (0.5 μmol/L) or MSDH (50 μmol/L).

Measurement of Viability and Apoptosis

Viability of cell cultures was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Cells were incubated with 0.25 mg/ml MTT for 2 hours at 37°C. The MTT solution was then removed and the formazan product dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm. Caspase-3–like activity was analyzed using the substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence was correlated to protein content.

Cholesterol Measurement

Cholesterol content of fibroblasts was measured in cell lysates using the Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), as described by the manufacturer. Cholesterol content in CHO cells was determined by reversed-phase, high-performance liquid chromatography using an established method.15 Cells were lysed in 0.2 mol/L NaOH and then mixed with methanol. Hexane was added, and the samples were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 minutes (4°C). The hexane phase was collected and dried down in a SpeedVac centrifuge (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA) and the lipids resuspended in 100 μl of isopropanol. Cholesterol content was expressed relative to cellular protein content.

Immunocytochemistry

For staining of mitochondria, cells were incubated with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (200 nmol/L, 30 minutes, 37°C; Invitrogen). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 20 minutes at 4°C. For visualization of cathepsin D, this was followed by methanol fixation (20 minutes, −20°C). After incubation in 0.1% saponin and 5% fetal bovine serum (20 minutes, room temperature), cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Cells were rinsed then incubated (1 hour, room temperature) with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to AlexaFluor 488 or AlexaFluor 594 (Invitrogen). To visualize unesterified cholesterol, cells were stained with filipin (125 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at room temperature. Coverslips were washed and mounted using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were examined using a Nikon Eclipse E600 laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) together with the EZC1 3.7 software (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) or a Nikon Eclipse TE2000U microscope (Nikon) with Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 MP confocal system (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software 1.42q (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). For each treatment, 10 images (5 each from two separate experiments) were analyzed. The lysosomal area was selected (from images capturing LAMP-2–stained lysosomes), and the filipin intensity within these areas was analyzed. The mean fluorescence value from each image was recorded, and the overall mean was calculated (n = 10). The intracellular bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMP) fluorescence was analyzed similarly.

Flow Cytometric Determination of LysoTracker Fluorescence

Cells were stained with 50 nmol/L LysoTracker Green DND-26 (Invitrogen) for 5 minutes at 37°C and detached by trypsinization. LysoTracker Green was excited using a 488-nm argon laser, and the resulting fluorescence was detected in the FL1 channel using a 530 ± 28 nm filter. We collected 10,000 cells, and data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton, Dickinson and Company).

Extraction of Cytosol

Cytosol was extracted using the cholesterol-solubilizing agent digitonin (Sigma-Aldrich). When used at low concentrations, digitonin permeabilizes the plasma membrane, which has high cholesterol content, but leaves intracellular membranes with lower cholesterol content intact. Cell culture dishes were incubated for 12 minutes, rocking on ice, in extraction buffer [250 mmol/L sucrose, 20 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 10 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 1 mmol/L ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)] containing the indicated concentrations of digitonin before the extraction buffer was withdrawn. The release of cytosolic content was measured as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity. LDH catalyzes the conversion of NADH to NAD+ and can be monitored as decreased absorbance of NADH. Samples were added to 1 ml of 0.1 mol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 90 μmol/L NADH, and 790 μmol/L pyruvate at 37°C, and the reaction was followed for 150 seconds in a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 340 nm. Disruption of the lysosomal membrane was analyzed by measuring the activity of the lysosomal enzyme N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG) in the isolated fraction. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 40 minutes in 125 μl of 0.2 mol/L citrate buffer containing 0.8 mmol/L 4-methylumbelliferyl-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranoside (NAG substrate; Sigma-Aldrich). The amount of the fluorescent product was determined at λex 356 nm and λem 444 nm. Proteins in the cytosolic fraction were precipitated by addition of trichloroacetic acid (final concentration 5%). After a 10-minute incubation on ice, proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 20800 × g for 15 minutes. The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (see below) containing 6 mol/L urea to dissolve the precipitated proteins and neutralized by the addition of 3 μl 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide. The isolated fraction was analyzed by immunoblot technique.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cell pellets were lysed in 63 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 10% glycerol, and 2% SDS, and protein determination was performed. Bromophenol blue (0.05%) and dithiothreitol (50 mmol/L) were added before the samples were heated to 95°C. Proteins were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (200 V, 60 mA/gel) and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (100 V, 250 mA, 1 hour). The membrane was blocked in 5% dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with polysorbate 20 (Tween 20) and probed with a primary antibody (diluted in 0.1% dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with polysorbate 20) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed and probed with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies, goat anti-mouse antibodies (P0448, P0447; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), or bovine anti-goat antibodies (sc-2350; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, immunodetection of the bound antibodies was performed using Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Equal protein loading was verified by analyzing the expression of GAPDH (for whole cell extract) and LDH (cytosolic extract). Reprobing of membranes was performed after stripping in 1% Tween, 0.1% SDS, and 0.2 mol/L glycine, pH 2.2 (55°C, 1 hour) or blocking in the presence of 1% sodium azide.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean and standard deviations. Data were statistically evaluated using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple comparisons. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman test. P values ≤0.05 are considered to be significant and marked with an asterisk in figures. Experiments were routinely performed at least three times.

Results

U18666A Treatment Results in Cholesterol Accumulation and Lysosomal Alterations but Does Not Affect Cell Viability

Treatment of human fibroblasts with 0.5 μg/ml U18666A induced a time-dependent increase in total cholesterol content that was significant after 24 hours and increased further after 48 hours of treatment (Figure 1A). Unesterified cholesterol can be specifically labeled using the antibiotic filipin.16 In untreated cells, we observed pale and diffuse filipin staining, whereas cells treated with U18666A revealed a punctate, perinuclear filipin staining pattern (Figure 1B) that colocalized with the lysosomal marker LAMP-2. No colocalization of filipin staining and mitochondria was detected (results not shown). U18666A treatment alone did not influence the viability of human fibroblasts as assessed by MTT assay and caspase-3 activity measurements (Figure 1, C and D). U18666A treatment caused an approximately 12-fold elevation of LysoTracker Green fluorescence as analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 1, E and F). This increase of the lysosomal compartment was associated with a time-dependent increase in the expression of the lysosomal protein LAMP-2 and the proforms of cathepsin D (Figure 1G). By immunostaining and quantification of fluorescence, U18666A-treated cells were shown to have increased levels of the phospholipid BMP, also known as lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA), which is found exclusively in the endo-lysosomal system (Figure 1H). Together, these results show that U18666A induces an up-regulation of the lysosomal system.

Figure 1.

U18666A treatment results in cholesterol accumulation and lysosomal alterations but does not affect cell viability. Human fibroblasts were treated with 0.5 μg/ml U18666A for the indicated times. A: Intracellular cholesterol content of cells exposed to U18666A (n = 3). B: Staining of unesterified cholesterol with filipin (red) and LAMP-2 (green) in untreated cells and cells pretreated with U18666A (48 hours). The blue emission of filipin has been changed to red to better visualize the colocalization. Scale bar = 5 μm. C: Viability of cells assessed by the MTT assay (n = 4). D: Caspase-3–like activity determined using the fluorescent substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC and correlated to total protein content (n = 4). E: Flow cytometry analysis of LysoTracker Green fluorescence staining in control (green silhouette) and U18666A-treated cells (48 hours; red contour). M1 gate denotes the highly fluorescent population. F: Quantification of cells with high LysoTracker Green fluorescence (M1 gate in E) (n = 4). G: Western blot analysis of the protein expression of cathepsin D (Cat D) and LAMP-2. GAPDH was used to verify equal protein loading. One representative blot out of three is shown. H: Immunostaining (left) and quantification of BMP fluorescence (right) in fibroblasts pretreated with U18666A (48 hours) or not. Scale bar = 20 μm. Results are presented as mean values with error bars representing SD (n = 10 images). Significant difference at *P ≤ 0.05.

Fibroblasts with High Cholesterol Content Are Protected from Apoptosis Induced by MSDH

To investigate whether lysosomal cholesterol overload could alter the cellular sensitivity to apoptosis, fibroblasts were pretreated with U18666A before exposure to the lysosomotropic detergent MSDH. Microscopic examination and viability analysis revealed that U18666A-treated cells were less susceptible to cell death induced by MSDH (Figure 2, A and B). Accordingly, U18666A prevented MSDH-induced caspase-3 activation (Figure 2C). When cells were exposed to MSDH for 24 hours and then transferred to standard culture conditions, there was 100% survival of U18666A-pretreated cells compared with 17% in non-pretreated cells, indicating that cell death signaling is not only delayed but prevented. No apoptosis protection was noted when cholesterol accumulation was omitted and U18666A only was added at the time of MSDH-exposure (results not shown), excluding a direct effect of U18666A on the apoptotic response.

Figure 2.

Fibroblasts with high cholesterol content are protected from apoptosis induced by MSDH. Human fibroblasts were pretreated with U18666A (0.5 μg/ml, 48 hours) to induce lysosomal cholesterol accumulation before exposure to the lysosomotropic detergent MSDH (15 μmol/L). A: Phase contrast images of cells exposed to MSDH for 24 hours. Scale bar = 20 μm. B: Viability of cell cultures after MSDH exposure as assessed by the MTT assay (n = 4). Viability is expressed as percentage of untreated cultures. C: Caspase-3–like activity after MSDH treatment determined using the fluorescent substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC and correlated to total protein content (n = 4). Asterisks represent statistically higher caspase-3–like activity in non-pretreated cells compared with U18666A-pretreated cells. D: Filipin staining of unesterified cholesterol in untreated cells, cells pretreated with U18666A, and cells pretreated with U18666A plus 25-HC (1 μg/ml, 48 hours). Scale bar = 20 μm. E: Viability of cultures pretreated with U18666A with or without 25-HC for 48 hours then exposed to MSDH (24 hours). Results are presented as mean values with error bars representing SD. Significant difference at *P ≤ 0.05.

To verify the importance of cholesterol for the cytoprotective effect, U18666A-induced cholesterol accumulation was reverted by exogenously supplied 25-HC (Figure 2D). Simultaneous treatment of cells with U18666A and 25-HC totally abolished the protective effect of U18666A on MSDH-induced apoptosis (Figure 2E).

Fibroblasts with High Cholesterol Content Are Less Sensitive to Apoptosis Induced by Staurosporine and Cisplatin

To investigate if the protective effect of U18666A was specific for apoptosis induced by a lysosomotropic agent or a more general phenomenon, cells were exposed to the protein kinase inhibitor STS and cisplatin, two established apoptosis inducers. Earlier we reported that exposure of human fibroblasts to STS results in an early release of cathepsins from lysosomes with subsequent activation of the mitochondrial pathway to apoptosis.17 Cisplatin, clinically used to treat various types of cancer, has been shown to induce apoptosis associated with LMP when added to cell cultures.18 The results show that pretreatment with U18666A protected cells from both STS-induced apoptosis and cisplatin-induced cell death (Figure 3, A–C), indicating that the protective effect of cholesterol accumulation is not limited to insults caused by lysosomotropic detergents directly targeting the lysosomal membrane.

Figure 3.

Fibroblasts with high cholesterol content are less sensitive to apoptosis induced by STS and cisplatin. Human fibroblasts were pretreated with U18666A (0.5 μg/ml, 48 hours) to induce lysosomal cholesterol accumulation before exposure to STS (0.1 μmol/L, 24 hours) or cisplatin (40 μg/ml; 48 hours). A: Phase contrast images of cells exposed to STS and cisplatin. Scale bar = 20 μm. Viability and caspase-3–like activity of cell cultures after STS (B) or cisplatin (C) exposure (n = 4–8). Viability was assessed by the MTT assay and is expressed as percentage of untreated cultures. Caspase-3–like activity was determined using the fluorescent substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC and correlated to total protein content (n = 4). Results are presented as mean values with error bars representing SD. Significant difference at *P ≤ 0.05.

Augmented Lysosomal Cholesterol Content Results in Increased Lysosomal Stability

Next, we investigated the effect of cholesterol accumulation on lysosomal stability. Double staining of cathepsin D and the lysosomal marker LAMP-2 showed a punctate lysosomal pattern in control cells (Figure 4A). After MSDH exposure, cathepsin D was partly found in the cytosol of non-pretreated cells, but it was still found colocalized with LAMP-2 in cells pretreated with U18666A. Due to difficulties in quantifying cathepsin D translocation using this method, lysosomal release was also estimated by extraction of the cytosolic fraction using digitonin, a detergent that selectively extracts cholesterol. Because the plasma membrane contains more cholesterol than membranes of intracellular organelles, an optimal concentration of digitonin solubilizes the plasma membrane but leaves organelles intact.19 As presented in Figure 4B, release of cytosolic content, assessed by measuring the activity of the cytosolic enzyme LDH, was similar in control and U18666A-pretreated cells. The release of lysosomal constituents, as determined by measurement of NAG activity, was affected by U18666A (Figure 4B). U18666A-treated cells had increased digitonin sensitivity, consistent with cholesterol accumulation in the lysosomal membrane. By using 20 μg/ml digitonin, the plasma membrane was permeabilized, but the lysosomal membrane was intact both in control and U18666A-treated cells. Thus, this concentration of digitonin was used to study the release of lysosomal content. By immunoblotting of extracted cytosol, we demonstrated that the MSDH-induced release of cathepsin D was reduced in U18666A-pretreated cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Augmented lysosomal cholesterol content results in increased lysosomal stability. Normal human fibroblasts were pretreated with U18666A (0.5 μg/ml, 48 hours) before exposure to MSDH (15 μmol/L). A: Immunocytochemical staining of cathepsin D and LAMP-2 after 2 hours of MSDH exposure. Scale bar = 10 μm. B: Evaluation of plasma membrane sensitivity (measured as LDH activity; n = 3) and lysosomal membrane sensitivity (measured as NAG activity; n = 3) to permeabilization with digitonin (0–200 μg/ml) in untreated (control) and U18666A-pretreated cells. Asterisk represents significantly higher NAG release in U18666A-treated cells compared with control cells. The release obtained using 200 μg/ml digitonin was regarded as maximum release (100%). C: Immunoblotting of cathepsin D (Cat D) in cytosolic fractions extracted using 20 μg/ml digitonin. LDH was used to verify equal cytosol loading. One representative blot of three is shown. D: Quantification of filipin colocalizing with LAMP-2 in human fibroblasts treated with U18666A for the indicated times (n = 10 images; each image showed at least 5 cells). Cholesterol and LAMP-2 colocalization is measured as the mean filipin fluorescence in LAMP-2–positive areas. E: Cells were pretreated with U18666A for 8, 24, and 48 hours then exposed to MSDH (1 hour). The cytosolic fraction was extracted using digitonin (20 μg/ml), and lysosomal release was measured as NAG activity. Extraction using 200 μg/ml digitonin is regarded as maximum lysosomal release. F: Correlation of lysosomal cholesterol content (as presented in D) and lysosomal stability (measured as the MSDH concentration required to result in 50% release of NAG in E). Results are presented as mean values with error bars representing SD. Significant difference at *P ≤ 0.05.

Next, we studied the relationship between lysosomal membrane stability and cholesterol content. Lysosomal cholesterol content was estimated by quantifying the amount of filipin fluorescence that colocalized with LAMP-2. In cells pretreated with U18666A, lysosomal accumulation of cholesterol was apparent after 8 hours of U18666A treatment and increased further until 48 hours (Figure 4D). Cells pretreated with U18666A for 8, 24, and 48 hours were then exposed to MSDH (0–50 μmol/L). Cytosolic fractions were isolated by digitonin extraction, and the release of lysosomal contents was measured using NAG activity as a marker. As presented in Figure 4E, approximately 25 μmol/L MSDH was required to release half of the lysosomal content (NAG) in control cells compared with 50 μmol/L in cell cultures that were allowed to accumulate cholesterol by U18666A treatment for 48 hours. The lysosomal cholesterol content was plotted against the MSDH concentration estimated to be required for release of 50% of the lysosomal content, and, as seen in Figure 4F, there was a linear relationship between lysosomal cholesterol content and lysosomal stability.

U18666A Treatment Is Not Associated with Altered Expression or Localization of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1, or Hsp70

Our results indicate that the protective effect of U18666A on apoptotic signaling is active at the level of LMP. To explore mechanisms other than increased lysosomal cholesterol content that may promote lysosomal stability by U18666A treatment, we investigated antiapoptotic proteins known to stabilize the lysosomal membrane. The antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Mcl-1 were investigated, but no alteration of expression (Figure 5A) or translocation to lysosomes (results not shown) could be detected in U18666A-treated cells. Similarly, no up-regulation of Hsp70 was observed (Figure 5A), and the staining pattern remained cytosolic after U18666A exposure (results not shown).

Figure 5.

U18666A treatment is not associated with altered expression or localization of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1, or Hsp70 but increased LC3-II levels. Fibroblasts were pretreated with 0.5 μg/ml U18666A for the indicated times. A: Expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and Hsp70 in fibroblasts with or without U18666A treatment. GAPDH was used to verify equal protein loading. One representative blot of two is shown. B: Expression of LC3 in human fibroblasts with or without U18666A treatment. GAPDH was used to verify equal protein loading. One representative blot of three is shown. C: Immunoblotting of LC3 in human fibroblasts pretreated with 3-MA (5 mmol/L, 1 hour) followed by U18666A treatment (48 hours).

Protective Effects of U18666A Are Not Due to Induction of Autophagy

Autophagy is a process by which damaged organelles, membranes, and proteins are removed and degraded within lysosomes; therefore, it is considered to be an important cellular protection mechanism. Autophagy can be monitored via the expression of LC3, which during autophagy is converted from the cytosolic form of LC3-I into LC3-II and incorporated in the autophagic membrane. As seen in Figure 5B, U18666A treatment was associated with an increased level of LC3-II. However, accumulation of LC3-II does not always result from an induction of autophagy. It can also reflect a failure of autophagosomal degradation. Pretreatment with 3-MA, an inhibitor of autophagy, did not prevent the accumulation of LC3-II seen on U18666A treatment (Figure 5C). These results indicate that the increased LC3-II expression is a result of decreased autophagosome degradation rather than increased formation; thus, autophagy induction is unlikely to be part of the U18666A-associated protective mechanism.

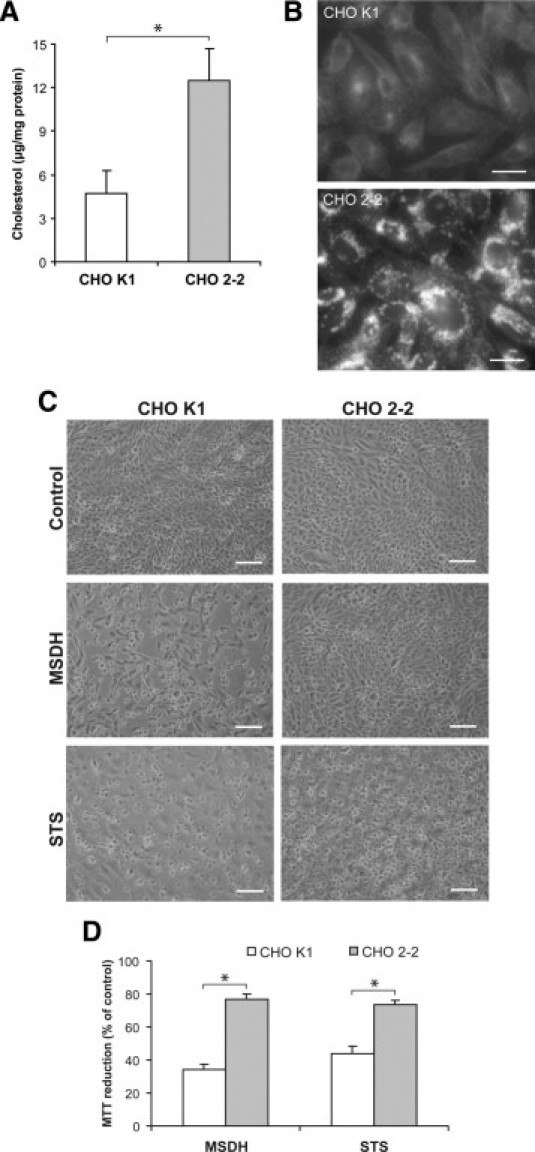

NPC-Deficient CHO Cells Are Less Sensitive to MSDH- and STS-Induced Apoptosis Than Wild-Type Cells

To verify our results that cholesterol accumulation, and not other U18666A-dependent mechanisms, protects cells from lysosome-dependent cell death signaling, we used the NPC1-deficient CHO 2-2 cell line along with wild-type CHO K1 cells. We established that CHO 2-2 cells had increased cholesterol content compared with the CHO K1 cells (Figure 6A) and that cholesterol was found in a punctate staining pattern indicating accumulation in the endo-lysosomal system (Figure 6B). In line with the results in the fibroblast model, CHO 2-2 cells showed higher resistance to apoptosis induced by MSDH and STS (Figure 6, C and D) compared with the CHO K1 cells.

Figure 6.

NPC-deficient CHO cells are less sensitive to MSDH- and STS-induced apoptosis than wild-type cells. A: Analysis of unesterified cholesterol content (n = 3). B: The cellular cholesterol localization using filipin in K1 (wild-type) and 2-2 (NPC-deficient) CHO cells. Scale bars = 20 μm. C: Phase-contrast images of CHO cells exposed to MSDH or STS. Scale bar = 100 μm. D: Viability of CHO cells exposed to MSDH (50 μmol/L, 24 hours) or STS (0.1 μmol/L, 24 hours). Viability is expressed as percentage of untreated cultures (n = 4). Results are presented as mean values with error bars representing SD. Significant difference at *P ≤ 0.05, as determined by nonparametric statistical testing.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate for the first time that accumulation of cholesterol in lysosomes attenuates release of proapoptotic cathepsins from lysosomes and thereby rescues cells from lysosome-dependent cell death. Human fibroblasts accumulated cholesterol and acquired an NPC-like phenotype in response to U18666A treatment. Cultures treated with U18666A showed increased expression of LAMP-2 and the proforms of cathepsin D, which concurs with recent studies showing that NPC1−/− mice have higher levels of cathepsins B and D compared with their wild-type littermates20 and that murine neurons exposed to U18666A express higher levels of cathepsin B and LAMP-2 mRNA.21 We also detected a higher intensity of LysoTracker fluorescence, indicating an up-regulation of the volume of the lysosomal system in response to U18666A exposure, which agrees with an earlier report.22 The phospholipid BMP, which is restricted to the internal membranes of late endosomes and lysosomes, has been studied during cholesterol accumulation, but the data have been inconclusive.23–25 Our data show that BMP is increased during U18666A treatment. Because BMP controls the cholesterol storage capacity of endosomes23 and has an important role in cholesterol transport,25 an increase in cellular levels of BMP may be a compensatory mechanism to cope with the cholesterol overload.

Lysosomotropic detergents specifically destabilize lysosomal membranes2 and cause the release of lysosomal content to the cytosol. This release precedes the mitochondrial alterations and morphological signs of apoptosis.3 We demonstrated that lysosomal cholesterol accumulation attenuated lysosomal leakage and thereby prevented cell death. U18666A treatment increased cholesterol levels in lysosomes and decreased the sensitivity toward MSDH-induced LMP, even though total cellular cholesterol level was unchanged. We also demonstrated a linear correlation between lysosomal cholesterol content and lysosomal stability. Although cholesterol is thought to accumulate mainly inside lysosomes,26 our observation that the lysosomal membranes of U18666A-treated cells have higher sensitivity to digitonin extraction compared with non-treated cells (Figure 4B) indicates a higher cholesterol content also of the limiting lysosomal membrane. These experiments also indicate that the cholesterol content of the plasma membrane is similar in control and U18666A-treated cells. This has been suggested in a previous study,27 but another study demonstrates plasma membrane cholesterol levels to be reduced in cells treated with U18666A.28

Impaired lipid transport is associated with deficient oxysterol production,29 which might be a part of the defect in sterol homeostasis in cells with the NPC phenotype. The oxysterol 25-HC is known to revert cholesterol accumulation induced by NPC1 mutations or U18666A exposure.29,30 This action of oxysterols is believed to be due to their activity as potent suppressors of sterol synthesis and acting as ligands for liver X receptors, which regulate cholesterol balance by activating genes that promote metabolism and elimination of excess cholesterol.31 To rule out a cholesterol-independent effect of U18666A, cells were cotreated with U18666A and 25-HC to prevent lysosomal cholesterol accumulation, and the protective effect of U18666A was abolished. Furthermore, our result demonstrates that cholesterol accumulation due to NPC1 deficiency also protects cells from apoptosis induced by MSDH or STS, excluding a nonspecific effect of U18666A. Together, these results indicate that cholesterol has an important role in maintaining the integrity of lysosomes during apoptosis.

Although the NPC disease is generally regarded to be a result of cholesterol efflux, the disease-associated trafficking defects also result in accumulation of other lipids, including sphingomyelin, glycosphingolipids, and sphingosine.32 In addition to increasing the cholesterol content of lysosomes, U18666A treatment is associated with accumulation of sphingosine.33 Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the results partly are due to the enrichment of lipids other than cholesterol or a general perturbation of the lipid balance within the lysosomal membrane. It should, however, be noted that sphingosine was demonstrated to induce LMP,34 arguing against a protective role of sphingosine accumulation in lysosomes.

Increased apoptosis frequency has been demonstrated in liver cells of NPC1−/− mice35 and in brains from NPC patients and NPC1−/− mice.36 Although NPC pathology is associated with cholesterol accumulation in basically every organ, neuronal death is what proves to be fatal in this disease. Lesions occur throughout the central nervous system, but certain cell populations, such as the Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum, are, for unknown reasons, more vulnerable.37 Apart from cholesterol accumulation, several factors have been described to contribute to neuronal death in NPC pathology, including increased oxidative stress, ER stress, deregulation of autophagy, inflammation, and energy deprivation.38,39 It is possible that factors not related to cholesterol accumulation have a pronounced role in sensitizing Purkinje neurons to apoptotic cell death, and this is an area that requires more detailed investigation. Although cholesterol accumulation may be unable to prevent Purkinje neuron apoptosis in the later stages of NPC disease, it is clear that most neurons survive for long periods of time with substantial amounts of cholesterol (and glycosphingolipid) storage and that prevention of LMP may play a role during the earlier stages of NPC disease. Consistent with this idea, cholesterol accumulation is evident in Purkinje cells from NPC1−/− mice at early time points when no signs of neuronal apoptosis or morphological alterations are present.40 Hypomyelination and axonal injury also could increase neuronal susceptibility,37 because neurons cultured from NPC1−/− mice exhibit altered cholesterol distribution with cholesterol accumulating in cell bodies, whereas distal axons had reduced cholesterol.41 Because axons perform crucial functions in neurons, such as signaling and synaptic transmission, a reduced cholesterol content of axons is likely to have severe consequences.

U18666A treatment and cholesterol accumulation per se did not affect cell viability in the cell system used in this report. Previously, it has been reported that U18666A induces apoptosis in lens epithelial cells, melanoma cells, and cultured murine neurons.42 However, no cytotoxic effects of U18666A (3 μg/ml for 72 hours) were observed in primary rat cortical neurons (H. Appelqvist, K. Björnström Carlsson, K. Öllinger, K. Kågedal, unpublished observations). Despite the massive lipid storage and extensive neuronal death in NPC1-deficient brains, survival of isolated NPC1−/− mouse neurons is not compromised under normal culture conditions,39 and only subtle differences in function have been observed in NPC1−/− neurons. Our discovery that cells with lysosomal accumulation of cholesterol are rescued from lysosome-dependent cell death demonstrates that increased cholesterol in lysosomes protects cells from acute toxic insults. However, for organs heavily loaded with lysosomal cholesterol, this may not be beneficial in the long run. Depending on the extent of lysosomal lipid loading, the benefits we have discovered regarding the capacity for cholesterol to prevent LMP may, in fact, be lost.

U18666A is an amphiphilic amine that has the ability to interact with and inhibit a diverse array of proteins, including proteins involved in sterol synthesis. However, the most likely effect is a general perturbation of membrane order.42 Our findings indicate that the protective effect of U18666A pretreatment is mainly a result of increased cholesterol content in the endo-lysosomal system. Accordingly, the NPC1-deficient CHO 2-2 cells were less sensitive to cell death induced by both STS and MSDH. It has been reported previously that U18666A treatment protects HeLa cells from apoptosis induced by actinomycin D and STS.43 In contrast, U18666A failed to protect macrophages from apoptosis induced by STS,44 suggesting a cell type–specific effect of U18666A.

Because the mere presence of cathepsins in the cytosol is sufficient to trigger apoptosis,4 the release of lysosomal constituents is well regulated. LAMP-2 expression has been shown to correlate with lysosomal stability,45 and in U18666A-treated cells, there was an increased expression of LAMP-2. The increased expression of LAMP-2 might be due to a universal enlargement of the lysosomal system. Recently, Schneede et al46 showed that LAMP-1/-2 double knockout fibroblasts accumulated cholesterol in the lysosomal system, which suggested a role for LAMP proteins in facilitating cholesterol efflux. Therefore, our finding of increased LAMP-2 expression might be interpreted as a feedback mechanism to increase the cholesterol efflux from lysosomes. Previous reports have demonstrated that Bcl-2 proteins, in addition to regulating the release of apoptogenic factors from mitochondria, modulate lysosomal permeability.5 No alterations in expression or translocation of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, or Mcl-1 to lysosomes could, however, be detected in U18666A-treated cells. Although Hsp70 is found at the lysosomal membrane in several cell systems and prevents LMP, we could not detect any alterations in expression or localization of Hsp70 after U18666A treatment.

The role of autophagy during cell death and neurodegeneration is complex because the autophagic process enables recycling of limiting and damaged cell constituents to promote cell survival but may result in death if overactivated. Areas subjected to neurodegeneration display evidence of autophagosome accumulation,20 and in agreement with our results, several reports have shown that U18666A treatment or NPC deficiency is associated with accumulation of LC3-II.47–49 Such accumulation might indicate an increase in autophagy but could also be a result of defective clearance of autophagosomes,50 and both explanations have been suggested to cause LC3-II accumulation during cholesterol overload. In our model, inhibition of autophagy using 3-MA did not prevent the U18666A-induced accumulation of LC3-II, indicating that LC3-II accumulation is a result of decreased autophagosome clearance. We speculate that cholesterol accumulation might disturb lysosomal function, including degradation of autophagosomes, and the increased expression of lysosomal proteins observed might indicate enhanced synthesis of lysosomes as a stress response to cope with the increased lysosomal load.

In conclusion, altered lysosomal function is implicated in a variety of pathological conditions including neurodegenerative disorders, inherited lysosomal storage disorders, and cancer.51,52 Our data show for the first time that cholesterol accumulation in lysosomes attenuates apoptosis by reducing lysosomal cathepsin D release. Increased knowledge of lysosomal function and the factors that regulate LMP has the potential to offer new therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kajsa Holmgren Peterson for skillful assistance with confocal microscopy and Stefan Lundqvist who, by his interest in Niemann-Pick diseases, prompted us to initiate this project.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the foundation of Olle Engkvist Byggmästare, the foundation of the family of Carl and Albert Molin in Motala minne, the Sven and Dagmar Salén foundation, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, and the Swedish Research Council.

References

- 1.Boya P., Kroemer G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:6434–6451. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Firestone R.A., Pisano J.M., Bonney R.J. Lysosomotropic agents. 1. Synthesis and cytotoxic action of lysosomotropic detergents. J Med Chem. 1979;22:1130–1133. doi: 10.1021/jm00195a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li W., Yuan X., Nordgren G., Dalen H., Dubowchik G.M., Firestone R.A., Brunk U.T. Induction of cell death by the lysosomotropic detergent MSDH. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberg K., Kågedal K., Öllinger K. Microinjection of cathepsin D induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson A.C., Appelqvist H., Nilsson C., Kågedal K., Roberg K., Öllinger K. Regulation of apoptosis-associated lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Apoptosis. 2010;15:527–540. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesmin B., Maxfield F.R. Intracellular sterol dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokol J., Blanchette-Mackie J., Kruth H.S., Dwyer N.K., Amende L.M., Butler J.D., Robinson E., Patel S., Brady R.O., Comly M.E. Type C Niemann-Pick disease: Lysosomal accumulation and defective intracellular mobilization of low density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3411–3417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liscum L., Faust J.R. The intracellular transport of low density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol is inhibited in Chinese hamster ovary cells cultured with 3-beta-[2-(diethylamino)ethoxy]androst-5-en-17-one. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11796–11806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung N.S., Koh C.H., Bay B.H., Qi R.Z., Choy M.S., Li Q.T., Wong K.P., Whiteman M. Chronic exposure to U18666A induces apoptosis in cultured murine cortical neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouchier F., Mego J.L., Dang J., Simon C. Thyroid lysosomes: the stability of the lysosomal membrane. Eur J Cell Biol. 1983;30:272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadot M., Andrianaivo F., Dubois F., Wattiaux R. Effects of methylcyclodextrin on lysosomes. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1392–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl N.K., Reed K.L., Daunais M.A., Faust J.R., Liscum L. Isolation and characterization of Chinese hamster ovary cells defective in the intracellular metabolism of low density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4889–4896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahl N.K., Daunais M.A., Liscum L. A second complementation class of cholesterol transport mutants with a variant Niemann-Pick type C phenotype. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:1839–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojtanik K.M., Liscum L. The transport of low density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol to the plasma membrane is defective in NPC1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14850–14856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedorow H., Pickford R., Hook J.M., Double K.L., Halliday G.M., Gerlach M., Riederer P., Garner B. Dolichol is the major lipid component of human substantia nigra neuromelanin. J Neurochem. 2005;92:990–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gimpl G., Gehrig-Burger K. Cholesterol reporter molecules. Biosci Rep. 2007;27:335–358. doi: 10.1007/s10540-007-9060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson A.C., Steen H., Öllinger K., Roberg K. Cathepsin D mediates cytochrome c release and caspase activation in human fibroblast apoptosis induced by staurosporine. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1253–1259. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson C., Roberg K., Grafstrom R.C., Ollinger K. Intrinsic differences in cisplatin sensitivity of head and neck cancer cell lines: correlation to lysosomal pH. Head Neck. 2010;32:1185–1194. doi: 10.1002/hed.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuurendonk P.F., Tager J.M. Rapid separation of particulate components and soluble cytoplasm of isolated rat-liver cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;333:393–399. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(74)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao G., Yao Y., Liu J., Yu Z., Cheung S., Xie A., Liang X., Bi X. Cholesterol accumulation is associated with lysosomal dysfunction and autophagic stress in NPC1−/− mouse brain. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:962–975. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh C.H., Qi R.Z., Qu D., Melendez A., Manikandan J., Bay B.H., Duan W., Cheung N.S. U18666A-mediated apoptosis in cultured murine cortical neurons: role of caspases, calpains and kinases. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1572–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobo K., Le Blanc I., Luyet P.P., Fivaz M., Ferguson C., Parton R.G., Gruenberg J., van der Goot F.G. Late endosomal cholesterol accumulation leads to impaired intra-endosomal trafficking. PLoS One. 2007;2:e851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chevallier J., Chamoun Z., Jiang G., Prestwich G., Sakai N., Matile S., Parton R.G., Gruenberg J. Lysobisphosphatidic acid controls endosomal cholesterol levels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27871–27880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanier M.T., Millat G. Niemann-Pick disease type C. Clin Genet. 2003;64:269–281. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi T., Beuchat M.H., Lindsay M., Frias S., Palmiter R.D., Sakuraba H., Parton R.G., Gruenberg J. Late endosomal membranes rich in lysobisphosphatidic acid regulate cholesterol transport. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramanian K., Balch W.E. NPC1/NPC2 function as a tag team duo to mobilize cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15223–15224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808256105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange Y., Ye J., Rigney M., Steck T. Cholesterol movement in Niemann-Pick type C cells and in cells treated with amphiphiles. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17468–17475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Underwood K.W., Jacobs N.L., Howley A., Liscum L. Evidence for a cholesterol transport pathway from lysosomes to endoplasmic reticulum that is independent of the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4266–4274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frolov A., Zielinski S.E., Crowley J.R., Dudley-Rucker N., Schaffer J.E., Ory D.S. NPC1 and NPC2 regulate cellular cholesterol homeostasis through generation of low density lipoprotein cholesterol-derived oxysterols. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25517–25525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange Y., Ye J., Steck T.L. Circulation of cholesterol between lysosomes and the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18915–18922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill S., Chow R., Brown A.J. Sterol regulators of cholesterol homeostasis and beyond: the oxysterol hypothesis revisited and revised. Prog Lipid Res. 2008;47:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lloyd-Evans E., Platt F.M. Lipids on trial: the search for the offending metabolite in Niemann-Pick type C disease. Traffic. 2010;11:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lloyd-Evans E., Morgan A.J., He X., Smith D.A., Elliot-Smith E., Sillence D.J., Churchill G.C., Schuchman E.H., Galione A., Platt F.M. Niemann-Pick disease type C1 is a sphingosine storage disease that causes deregulation of lysosomal calcium. Nat Med. 2008;14:1247–1255. doi: 10.1038/nm.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kågedal K., Zhao M., Svensson I., Brunk U.T. Sphingosine-induced apoptosis is dependent on lysosomal proteases. Biochem J. 2001;359:335–343. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beltroy E.P., Richardson J.A., Horton J.D., Turley S.D., Dietschy J.M. Cholesterol accumulation and liver cell death in mice with Niemann-Pick type C disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:886–893. doi: 10.1002/hep.20868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y.P., Mizukami H., Matsuda J., Saito Y., Proia R.L., Suzuki K. Apoptosis accompanied by up-regulation of TNF-alpha death pathway genes in the brain of Niemann-Pick type C disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;84:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka J., Nakamura H., Miyawaki S. Cerebellar involvement in murine sphingomyelinosis: a new model of Niemann-Pick disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1988;47:291–300. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198805000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bi X., Liao G. Cholesterol in Niemann-Pick Type C disease. Subcell Biochem. 2010;51:319–335. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-8622-8_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karten B., Peake K.B., Vance J.E. Mechanisms and consequences of impaired lipid trafficking in Niemann-Pick type C1-deficient mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid P.C., Sakashita N., Sugii S., Ohno-Iwashita Y., Shimada Y., Hickey W.F., Chang T.Y. A novel cholesterol stain reveals early neuronal cholesterol accumulation in the Niemann-Pick type C1 mouse brain. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:582–591. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D300032-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karten B., Vance D.E., Campenot R.B., Vance J.E. Cholesterol accumulates in cell bodies, but is decreased in distal axons, of Niemann-Pick C1-deficient neurons. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1154–1163. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cenedella R.J. Cholesterol synthesis inhibitor U18666A and the role of sterol metabolism and trafficking in numerous pathophysiological processes. Lipids. 2009;44:477–487. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucken-Ardjomande S., Montessuit S., Martinou J.C. Bax activation and stress-induced apoptosis delayed by the accumulation of cholesterol in mitochondrial membranes. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:484–493. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng B., Yao P.M., Li Y., Devlin C.M., Zhang D., Harding H.P., Sweeney M., Rong J.X., Kuriakose G., Fisher E.A., Marks A.R., Ron D., Tabas I. The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:781–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fehrenbacher N., Bastholm L., Kirkegaard-Sorensen T., Rafn B., Bottzauw T., Nielsen C., Weber E., Shirasawa S., Kallunki T., Jäättelä M. Sensitization to the lysosomal cell death pathway by oncogene-induced down-regulation of lysosome-associated membrane proteins 1 and 2. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6623–6633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneede A., Schmidt C.K., Hölttå-Vuori M., Heeren J., Willenborg M., Blanz J., Domanskyy M., Breiden B., Brodesser S., Landgrebe J., Sandhoff K., Ikonen E., Saftig P., Eskelinen E.L. Role for LAMP-2 in endosomal cholesterol transport. J Cell Mol Med. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bi X., Liao G. Autophagic-lysosomal dysfunction and neurodegeneration in Niemann-Pick Type C mice: lipid starvation or indigestion? Autophagy. 2007;3:646–648. doi: 10.4161/auto.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng J., Ohsaki Y., Tauchi-Sato K., Fujita A., Fujimoto T. Cholesterol depletion induces autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pacheco C.D., Kunkel R., Lieberman A.P. Autophagy in Niemann-Pick C disease is dependent upon Beclin-1 and responsive to lipid trafficking defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1495–1503. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mizushima N., Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nixon R.A., Yang D.S., Lee J.H. Neurodegenerative lysosomal disorders: a continuum from development to late age. Autophagy. 2008;4:590–599. doi: 10.4161/auto.6259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirkegaard T., Jäättelä M. Lysosomal involvement in cell death and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]