Abstract

Human embryonic stem cells differentiated under mesoderm-inducing conditions have important therapeutic properties in sepsis-induced lung injury in mice. Single cell suspensions obtained from day 7 human embryoid bodies (d7EBs) injected i.v. 1 hour after cecal ligation and puncture significantly reduced lung inflammation and edema as well as production of tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ in lungs compared with controls, whereas interleukin-10 production remained elevated. d7EB cell transplantation also reduced mortality to 50% from 90% in the control group. The protection was ascribed to d7EB cell interaction with lung resident CD11b+ cells, and was correlated with the ability of d7EB cells to reduce it also reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines by CD11+ cells, and to endothelial NO synthase–derived NO by d7EB cells, leading to inhibition of inducible macrophage-type NO synthase activation in CD11b+ cells. The protective progenitor cells were positive for the endothelial and hematopoietic lineage marker angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). Only the ACE+ fraction modulated the proinflammatory profile of CD11b+ cells and reduced mortality in septic mice. In contrast to the nonprotective ACE-cell fraction, the ACE+ cell fraction also produced NO. These findings suggest that an ACE+ subset of human embryonic stem cell–derived progenitor cells has a highly specialized anti-inflammatory function that ameliorates sepsis-induced lung inflammation and reduces mortality.

Lung inflammatory injury from septic shock is the leading cause of death in patients in the intensive care unit,1 with mortality remaining at ∼40%.2 The disease is characterized by progressive respiratory failure with bilateral alveolar infiltrates and lung edema.3 Transplantation of adult bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells, endothelial progenitor cells, and bone marrow–derived progenitor cells has been studied in models of sepsis4–11; however, the results have varied, and specific cell populations responsible for the protection have not been characterized. Although in some cases transplanted cells differentiated into specialized parenchymal cells,7,10 the lung repair observed may also be secondary to immunomodulatory effects of the transplanted cells.4,6,8

Previous studies have not addressed the effects of a well-defined progenitor population derived from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in resolution of sepsis-induced lung injury. Because ESCs are pluripotent, it was surmised that specific progenitors derived from ESCs could effectively mitigate sepsis-induced lung inflammation and injury. Using blast progenitor cells from human ESCs (hESCs) cultured in conditions favoring development of mesoderm,12 the present study addressed the role of a purified population of progenitor cells in the lung response to polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). It was observed that transplantation of hESC-derived progenitor cells after induction of sepsis reduced lung inflammation and edema formation, and it also reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) without affecting production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)–10. Recipient mice also demonstrated marked reduction in mortality. Dampening of lung inflammation was the result of progenitor cells enriched with the endothelial and hematopoietic progenitor cell marker angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and was largely ascribed to the interaction of these cells with CD11b+ cells in lungs. This interaction in turn mediated reduction in production of proinflammatory cytokines and high-output NO production by CD11b+ cells.

Materials and Methods

Differentiation of hESCs into Embryoid Bodies

hESCs (H1, XY, WiCell, and National Institutes of Health–approved WA01) were maintained on mitomycin-blocked mouse embryonic fibroblast feeders in hESC growth medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and Ham nutrient mixture F-12) supplemented with 15% knockout serum replacement enriched with 4 ng/ml of human basic fibroblast growth factor-2, 1× nonessential amino acid, 1× glutamax-I, and 1× β-mercaptoethanol (all from Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Half of the medium was changed every 48 hours until the colonies were close to confluence. For differentiation induction, 2 to 2.5 × 106 hESCs were resuspended in 3 ml of stem cell medium (HEScGro; Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) supplemented with 50 ng/ml of vascular endothelial growth factor and 50 ng/ml of bone morphogenetic protein-4, plated in one well of a six-well plate (Ultra-Low; Corning Inc., Corning, NY), and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 hours, 40 ng/ml of stem cell factor, 40 ng/ml of thrombopoietin, and 40 ng/ml of Fms-related tyrosine kinase-3 (Flt3) ligand (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) were added to the cultures, followed by 25 ng/ml each of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-6, and IL-3, and 3 U/ml of human erythropoietin at day 3½ of differentiation culture.

Differentiation of hESCs into Endothelial and Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells

d7EB cells were fractionated using fluorescein-activated cell sorting (FACS) for ACE and kinase insert domain receptor (KDR) expression. The isolated fractions were subcultured on fibronectin-coated plates in the presence of endothelial cell basal medium and 20 ng/ml of stem cell factor, 20 ng/ml of thrombopoietin, 20 ng/ml of Fms-related tyrosine kinase-3 ligand, 25 ng/ml each of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-6, and IL-3, and 1 U/ml of human erythropoietin.

Mouse Sepsis Model

Studies were performed using 6- to 8-week-old male CD1 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), which were housed in pathogen-free conditions at the University of Illinois animal care facility. Experimental sepsis was induced via CLP performed as previously described.13 In brief, after proper sterilization, the cecum was exposed via a midline abdominal incision and ligated at 75% of the distance between the distant cecal pole and the base of the cecum, followed by a 21-gauge needle puncture in a mesenteric toward antimesenteric direction. Wound closure was achieved using separate sutures (6-0 nylon) to the abdominal musculature and the skin. Immediately after the procedure, 500 μL of warmed normal saline solution was administered subcutaneously. For survival studies, the mice were monitored every 6 hours for 24 hours, and thereafter every 12 hours for 5 days. All cell injections were administered 1 hour after CLP via i.v. administration through the facial vein. Studies were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines, and approval was obtained from the institutional review board.

Induction of Immunosuppression

In some xenotransplantation studies, cyclosporine A (CsA) was administered as an oral solution diluted with corn oil at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. The CsA was administered p.o. via gavage at a dose of 75 mg/kg/d, beginning 1 day before CLP and continuing for another 24 hours after the procedure.14 Pilot experiments demonstrated efficiency of this dosage in inhibiting production of IL-2 and IFN-γ by T cells isolated from mouse spleens.

Lung Tissue Myeloperoxidase Content

Lung tissue neutrophil (polymorphonuclear leukocyte) uptake was assessed via determination of myeloperoxidase activity. Lungs were dried and homogenized in 1.0 ml of PBS (50 mmol/L, pH 6.0) with 5% hexadecyl-trimethylammonium bromide and 5 mmol/L of EDTA. Homogenates were sonicated, centrifuged at 4 × 104 g for 20 minutes and were frozen and thawed twice, followed by homogenization and centrifugation. The supernatant was mixed 1:30 (v/v) with assay buffer (0.2 mg/ml of o-dianisidine hydrochloride and 0.0005% H2O2), and absorbance change was measured at 460 nm for 3 minutes. Myeloperoxidase activity based on dry lung weight was calculated as the change in absorbance over time.15

Lung Vascular Permeability Measurement

Lung capillary filtration coefficient was measured to quantify lung vascular permeability, as described previously.16 Venous outflow pressure was elevated using a computer-controlled two-way electronic pinch valve (P/N 98301-22; Cole-Parmer Instrument Co., Vernon Hills, IL) that channeled venous fluid into silicon tubing (1/16-inch i.d.). The weight change resulting from the venous pressure increase of 6 cm of water was recorded for 5 minutes. The weight recording has two exponential components that reflect the rapid expansion of vascular volume and the slower phase of transvascular fluid filtration. The amount of fluid filtered in 5 minutes was determined via logarithmic extrapolation of the slower component to time 0. The lung capillary filtration coefficient, a measure of lung vascular liquid permeability, was computed as milliliters per minute per centimeter of water per gram dry weight by normalizing the estimate of filtered fluid by time, venous pressure change, and lung dry weight.

Isolation and Depletion of Lung CD11b+ Cells

At 6 and 12 hours after CLP, lungs were removed from euthanized mice, minced into small pieces, and incubated in RPMI-1640 medium with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% glutamine for 30 minutes at 37°C and at 5% CO2 in the presence of 1 mg/ml of collagenase type 1 and 50 U/ml of deoxyribonuclease I. After incubation, cells were filtered through a 70-mm cell strainer and washed with RPMI medium. The cells were incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with CD11b magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotek, Inc., Auburn, CA) and subsequently applied to MS columns (Miltenyi Biotek, Inc.) for their positive selection. Negatively selected cells were also collected.

For CD11b+ depletion studies, 24 hours before experimental procedures, mice were injected i.v. with gadolinium chloride, 10 μg/g body weight; anti–Gr-1, 50 μg per mouse; and anti–NK1.1, 50 μg per mouse. Depletion of CD11b+ cells was verified using flow cytometry.

Histologic Analysis and Immunohistochemistry

Mouse lungs were inflated with 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples were cut into 5-μm sections, mounted on slides (Starfrost Plus; Maenzel Glaeser, Braunschweig, Germany), and hydrated using an alcohol gradient. Slides were rinsed in distilled water, followed by antigen unmasking using a 10× concentrated retrieval solution (antigen decloaker solution; Biocare Medical Inc., Concord, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and rinsed in PBS for 5 minutes. For detection of human laminin A1, tissue sections were blocked with H2O2 blocking reagent for 10 minutes at room temperature. Slides were treated with a protein-blocking solution for 10 minutes at room temperature, rinsed, and incubated with human anti-laminin monoclonal antibody (L8271, clone LAM 89; Sigma Aldrich Corp., St Louis, MO) at a titer of 1:1000 for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (EnVision FLEX+ autostainer kit; Daco A/S, Glostrup, Denmark). Slides were rinsed and treated using the mouse-on-mouse polymer kit (MM510; Biocare Medical Inc.) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Laminin staining was detected using a betazoid diaminobenzidine kit (Biocare Medical Inc.). Human tonsil tissue stained with anti-laminin monoclonal antibody was used as positive control, and the same tissue stained only with the secondary anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase served as the negative control.

Immunocytochemistry

d7EB cells were fractionated using FACS according to their cell surface expression of ACE and KDR and were subcultured on 35-mm fibronectin-coated dishes on top of No. 1.5 coverslips (0.16−0.19 mm). After 2 weeks, the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with paraformaldehyde 4% in PBS for 30 minutes, washed with 100 mmol/L of glycine in PBS, and incubated for 1 hour with blocking buffer containing 2% to 5% normal donkey serum, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% Triton X-100. Subsequently, they were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with primary antibodies against human vascular endothelial cadherin, von Willebrand factor, and CD43 at 1:200 dilution in 2% normal donkey serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% Triton-X in PBS. Control cells were incubated with goat IgG, rabbit IgG, and mouse IgG1, respectively, under the same conditions. After washing with PBS and repeat blocking for 1 hour, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies Alexa 488 anti-goat IgG, Alexa 568 anti-rabbit IgG, or Alexa 568 anti-mouse IgG1 at 1:700 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature.

Labeling for Stem Cell Tracking

Single cell suspensions were created from d7EB cells via brief trypsinization. The cells were then fluorescently labeled via incubation with 10 μmol/L of carboxy-fluorescein diacetate (Green Tracker, C2925; Invitrogen Corp.) in serum-free medium for 30 minutes at 37°C. Labeling was confirmed at fluorescence microscopy, and cells were kept on ice until use. Carboxy-fluorescein diacetate–labeled green fluorescent cells, 5 × 105, were injected i.v. through the facial vein. For cell tracking studies, mice were sacrificed at 6, 18, and 24 hours after injection, and 5-μm snap-frozen lung sections were cut. Tissues were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole) and examined for native green fluorescence at confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope; Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Sections were graded using a semiquantitative scale established by counting the number of fluorescent cells per 100 nuclei per power field examined at 40× magnification (0 = no florescence, 1 = ≤1 fluorescent cell, 2 = 1 to 5 fluorescent cells, 3 = >5 fluorescent cells). Ten power fields per slide were examined by two independent reviewers blinded to the animal group.

Lung Edema Determination

Extravascular lung water content was measured via determination of lung wet- to dry-weight ratios in which intravascular lung water was corrected using a hemoglobin assay of lung homogenates and peripheral blood.4

Flow Cytometry

The following antibodies were used for flow cytometry studies and FACS: mouse anti-CD11b Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated (clone M1/70; isotype, rat IgG2b-488); mouse anti-F4/80 (clone 6F12; isotype, rat IgG2a); mouse anti-NK1.1 PE-conjugated (clone PK136; isotype, mouse IgG2a-PE); mouse anti-Gr1 PE-conjugated (clone RB6-8C5; isotype, mouse IgG2a-PE); rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG 1.2; isotype, rat IgG1); rat anti-mouse IL-10 (clone JES5-16E3; isotype, rat IgG2b); biotin mouse anti-human TLR4 (clone HTA 125; isotype, mouse IgG2a-biotin); and biotin anti-Annexin V (all from BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); mouse anti-KDR PE-conjugated (isotype, mouse IgG1-PE) and mouse anti-ACE fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated (isotype, goat IgG–fluorescein isothiocyanate) (both from R&D Systems, Inc.); rat anti-mouse TNF-α (clone MP6-XT22; isotype, rat IgG1; Invitrogen Corp.); rabbit polyclonal anti-NOS2, (clone N-20; isotype, goat IgG; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); and NO-Cu-Fl, final concentration 10 μmol/L (Intracellular Nitric Oxide Sensor Kit, catalog No. 96–0293; Strem Chemicals, Inc., Newburyport, MA). For intracellular staining, mouse lung cells were first fixed via incubation using 100 μL of fixation buffer (eBioscience, Inc., San Diego, CA) for 20 minutes at room temperature, and washed twice with 1 ml of permeabilization buffer (eBioscience, Inc.). Consequently, 1 to 5 μg/106 cells of antibodies against TNF-α, IL-10, IFN-γ, or inducible NO synthase (iNOS) were then added in 100-μL volume of permeabilization buffer, and cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. After an additional washing with 1 ml of permeabilization buffer, the cells were stained with secondary anti-rat–fluorescein isothiocyanate or anti-rabbit–PE (iNOS) conjugated antibody for 20 minutes at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in flow cytometry buffer and analyzed immediately. Intracellular NO staining with fluorescent-bound copper was performed per the manufacturer's instructions and in accordance with published protocols.17,18 Surface and intracellular marker expression were analyzed using software (LSR and CellQuest Pro; Becton Dickinson & Co., San Jose, CA).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were performed on supernatants of lung homogenates and cell culture supernatants using kits for mouse-specific TNF-α (Mouse TNF-α/TNFSF1A Quantikine ELISA Kit, MTA00); IFN-γ (Mouse IFN-γ Quantikine ELISA Kit, MIF00); and IL-10 (Mouse IL-10 Quantikine ELISA Kit, M1000) (all from R&D Systems, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Co-culture Experiments

Single-cell suspensions of mouse lung CD11b+ and CD11b− cells were prepared and plated in 24-well plates at a concentration of 106 cells in 1 ml of complete RPMI-1640 for 1 hour. The supernatants were removed, and 2 × 105 d7EB cells in fresh medium were added either directly with the mouse cells or on the insert membrane of the Transwell system (HTS Transwell 0.4-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane; Corning, Inc.). As a control, CD11b+ cells were plated without d7EB cells. The co-cultured cells were or were not stimulated with 1 μg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 6 hours. At the end of the stimulation period, the supernatants were collected, and mouse-specific ELISAs (R&D Systems, Inc.) were performed on samples to detect the released mouse TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10. This protocol was repeated for the experiments with ACE and KDR sorted d7EB cells.

Assay for NO and NO-Derived Products

Concentrations of NO and nitrite were determined using an NO analyzer (NOATM280; Sievers Instruments, Inc., Boulder, CO). NO concentrations were determined via analysis of nitrite accumulation in the culture supernatants of co-cultured d7EB cells and CD11b+ cells or CD11b+ cells alone. Media aliquots were collected at the indicated times, and were injected directly into the analyzing cell containing the reducing solution (saturated sodium iodide in 50% acetic acid). The analysis was conducted at room temperature. Authentic NaNO2 solutions of known concentrations were used as standards. For determination of NO production from human d7EB cells, cultures were washed twice with fresh serum-free media. Medium containing 1 μg/ml of LPS was replenished, and cells were undisturbed for the duration of the experiment. Media samples were collected at selected times, and NO production was assessed as nitrite accumulated in the media.

NO Donor Experiments

Single-cell suspensions of CD11b+ cells were prepared from septic mice as described above. The cells were plated in 24-well plates at a concentration of 106 cells in 1 ml of complete RPMI-1640 medium for 1 hour. The supernatants were removed, and fresh medium was added in the presence or absence of LPS, 100 ng/ml, plus a series of concentrations of the NO donor diethylenetriamine (DETA) NONOate for 12 hours. The range of concentrations was chosen to mimic approximately the amount of NO produced by d7EB cells as determined by direct measurements as described above. At the end of the experiment, supernatant free of cells was collected for cytokine measurements via ELISA.

Generation of Conditioned Medium

Human d7EB cells were plated in 24-well plates at concentration of 2 × 106 cells in 1 ml of growth medium. Cells were cultured overnight in the presence or absence of LPS, 1 μg/ml. The supernatant was collected, spun down for 10 minutes at 500g to remove possible cell contamination, and injected i.v. into septic mice 1 hour after CLP at a volume of 200 μL per mouse.

Western Blot Analysis

CD11b+ cells were either co-cultured with d7EB cells as described above, exposed to DETA NO, or cultured alone. After stimulation with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for 12 hours, the cells were lifted by gentle scraping. Human cells, which do not express CD11b, were removed via positive selection using CD11b magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotek, Inc.). Live CD11b+ cells were lysed in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail, 60 μL/10 ml PBS (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were collected, and the protein concentration of each sample was measured using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). For each sample, 50 μg of protein was loaded onto lanes of NuPAGE 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen Corp.). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore Corp.). After incubation in blocking solution (5% dry milk in Tris-buffered saline solution with Tween 20) at room temperature for 1 hour, membranes were immunoblotted (24 hours at 4°C) with anti-iNOS rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab3523) and anti-eNOS mouse monoclonal antibody (ab76199) (both from Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), followed by secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit or mouse (1:1000). Peroxidase labeling was detected using the ECL Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Tumorigenesis Assay

Five NOD/SCID mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 106 d7EB cells in the dorsal region, and the animals were observed for 6 months for development of teratomas. At the end of the observation period, the injection areas were dissected and stained with H&E. No evidence of teratomas was observed in any of the animals.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed and figures generated using commercially available software (Prism version 4.03; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Quantitative data are given as mean (SEM). Comparison between transplant and control groups was made using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Survival between intervention and control groups was compared using the log-rank test.

Results

d7EB Cell Transplantation Prevents Sepsis-Induced Lung Inflammatory Injury and Reduces Mortality in Mice

First, the effects of d7EB cells on sepsis-induced lung inflammatory injury and death induced via CLP were determined. Because the studies involved transplantation of human progenitor cells in mice, the question of xenotransplantation was considered. In mice treated with CsA, transplantation of human d7EB cells (500,000 cells in 200 μL of PBS) reduced mortality after lethal CLP, from 10% in control mice receiving mitomycin-blocked mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to approximately 40% in the transplant group (Figure 1A). Although the CsA-immunosuppressed septic model proved useful in establishing a therapeutic role for human cells, there remained the important bias of pharmacologic immunosuppression in the sepsis model. Based on findings that ESCs and adult bone marrow stromal cells19–22 might not be strongly immunogenic because they generally lack major histocompatibility complex class II antigens,23 the effectiveness of these cells in immunocompetent septic mice without the complicating effects of previous immunosuppression was evaluated. Human d7EB cells in these mice were as protective against CLP-induced death as demonstrated in CsA-treated mice; that is, survival improved from less than 10% at 48 hours after CLP in control mice to 50% in the transplant group (Figure 1B). Also investigated were alterations in lung vascular permeability and edema formation at 24 hours after CLP. d7EB cell transplantation significantly reduced neutrophilic lung inflammation and lung edema and prevented lung endothelial barrier dysfunction in treated mice compared with the control group (Figure 2, A–D). The improvement in lung injury and survival was associated with decreased production of TNF-α and IFN-γ in septic lungs, whereas there was no change in IL-10 production (Figure 2E). Despite the absence of immunosuppression, d7EB cells were not immediately rejected, and their presence in recipient mouse lungs was verified up to 24 hours after cell transplantation. Increased numbers of cells were observed in the recipient lungs at 1 and 3 hours after transplantation, as demonstrated by human-specific laminin staining (Figure 3A). The number of cells in the lungs gradually decreased, but cells were still detectable during the first 24 hours (Figure 3B); however, no cells were visible at 48 hours after administration (data not shown). To determine whether the protection induced by d7EB cells could be ascribed to secreted factors, cultured d7EB cells were stimulated overnight with LPS, 1 μg/ml, or medium alone. Addition of LPS-conditioned medium obtained from d7EB cells did not alter mortality in mice that underwent CLP compared with controls injected with nonconditioned medium or PBS (Figure 3C), indicating that d7EB cells were essential for protection.

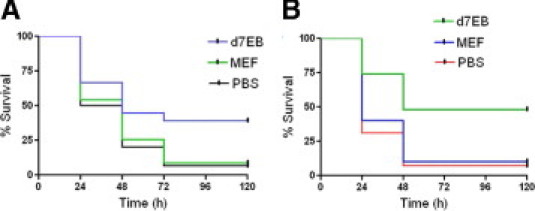

Figure 1.

Transplantation of d7EB human progenitor cells improves sepsis-induced mortality. A: Transplantation of CsA-immunosuppressed mice with human d7EB cells (500,000 cells in 200 μL of PBS) 1 hour after abdominal sepsis induced by CLP significantly improved survival from 10% in the MEF-transplanted control group to 40%. N = 30 in each group; P < 0.0001, log-rank test. B: d7EB cell transplantation in immunologically intact mice significantly improved survival after CLP. d7EB and MEF control cells (500,000 in 200 μL of PBS) were injected i.v. 1 hour after CLP. At the end of 120 hours of observation, survival in the control group receiving MEF was 10% versus 50% in the d7EB cell recipient group. N = 30 in each group. P < 0.0001, log-rank test.

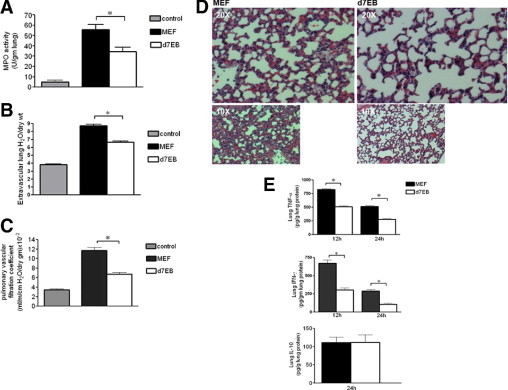

Figure 2.

Transplantation of d7EB human progenitor cells improves sepsis- induced lung inflammatory injury. A: Transplantation of d7EB cells reduced lung neutrophil sequestration, as measured using lung tissue myeloperoxidase activity, 24 hours after CLP. Controls were nonseptic mice. N = 15 in each group. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM. B: Transplantation of d7EB cells reduced lung edema formation induced by CLP. Cells (500,000 in 200 μL of PBS) were injected 1 hour after CLP. Extravascular lung water content was measured 24 hours after CLP for determination of lung wet- to dry-weight ratios. Controls are nonseptic mice. N = 15 in each group. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM. C: Transplantation of d7EB cells dampened the increase in pulmonary vascular permeability, as measured using pulmonary capillary filtration coefficient (Kf,c), 24 hours after CLP. Controls were nonseptic mice. N = 5 in each group. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM. D: Transplantation of d7EB cells improved lung architecture after CLP. Representative images of H&E-stained lung sections were obtained 24 hours after CLP. Magnification ×20, ×10. E: Reduced lung TNF-α and IFN-γ production after d7EB cell transplantation. TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 were measured in whole-lung tissue at the indicated times after induction of CLP. Transplantation of d7EB cells significantly reduced TNF-α and IFN-γ production but did not change IL-10 production. N = 10 in each group. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM.

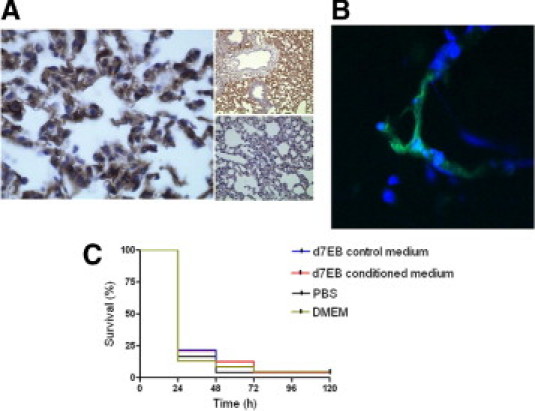

Figure 3.

Presence of d7EB cells in the lungs is required for their protective effect. A: Detection of human d7EB cells in mouse lungs. Tissue samples were prepared from lungs of septic mice removed 3 hours after i.v. transplantation of human cells. Left panel, Lungs were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, and were stained with human anti-laminin A1 monoclonal antibody. Magnification ×20. Upper small panel, Lung injected with d7EB cells; magnification ×10. Lower small panel, Lung injected with MEF; magnification ×10. Images are representative of at least 3 experiments. B: D7EB cells tagged with green fluorescent cell tracker were injected i.v. 1 hour after lethal CLP, and lungs were removed 18 hours later. Tissues were snap-frozen, cut into 5-μm sections, and examined for native fluorescence at confocal microscopy. Nuclei have been counterstained with DAPI. Magnification ×40. Image is representative of at least 3 experiments. C: d7EB-conditioned medium has no effect on sepsis-induced mortality. In contrast to d7EB transplanted cells, conditioned medium from d7EB cells injected 1 hour after CLP did not prevent death. In this experiment, 2.5 × 106 d7EB cells in 1 ml of medium were stimulated or not stimulated in vitro with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for 12 hours. The supernatant was collected, centrifuged to remove any cells, and injected i.v. in mice 1 hour after CLP at a volume of 200 μL per mouse. The two control groups received an equal volume of either DMEM/F-12 growth medium not exposed to d7EB cells or sterile PBS. N = 25 in each group.

Interaction of d7EB Cells and CD11b+ Cells Mediates Lung Protection

Because the primary source of TNF-α and IFN-γ in inflamed lungs is CD11b+ cells, that is, resident macrophages, blood monocytes, granulocytes, and natural killer cells,24 the possibility that d7EB cell interaction with host CD11b+ cells might induce an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile was investigated. CD11b+ cells were isolated from lungs of septic mice treated with either d7EB cells or MEFs. These cells were then stimulated with LPS in culture in the presence of the intracellular protein transport inhibitor Golgi stop. Cytokine staining showed that lung CD11b+ mouse cells obtained after d7EB cell transplantation produced significantly less TNF-α and IFN-γ (Figure 4A) compared with lung CD11b+ cells from mice receiving control MEF. These responses were not observed in CD11b− cells (Figure 4A).

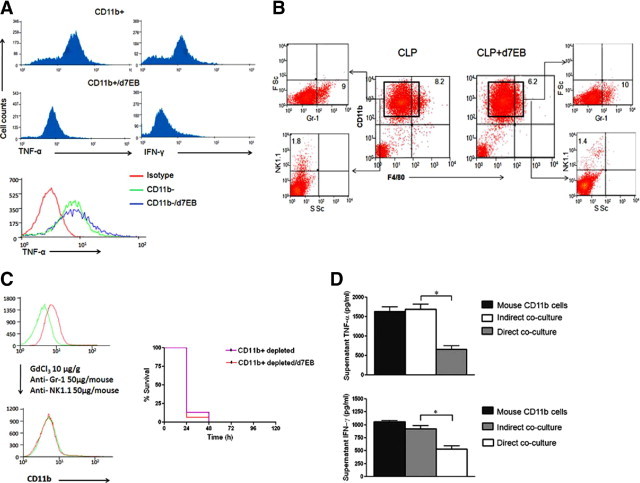

Figure 4.

Transplantation of d7EB progenitor cells favorably alters cytokine production profile of CD11b+ cells in lungs. A: Reduced production of TNF-α and IFN-γ by CD11b+ cells obtained from lungs of mice that received d7EB cells. Lung CD11b+ cells were isolated 12 hours after CLP from mice transplanted with and without d7EB cells (see Materials and Methods). The cells were then treated in vitro with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for 4 hours in the presence of Golgi stop and stained for TNF-α and IFN-γ. Intracellular TNF-α and IFN-γ levels decreased in CD11b+ cells exposed in vivo to human d7EB cells. The effect was specific to CD11b+ cells and was not observed in CD11b− cells. B: d7EB cells did not alter CD11b+ subpopulations in septic lungs. CD11b+ cells were isolated from the lungs of septic mice via magnetic beads. Cell surface expression of monocyte (F4/80), polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Gr-1), and natural killer cell (NK1.1) markers was examined using flow cytometry. No significant differences were noted between mice that received d7EB cells versus those who received MEF. Results are representative of 3 experiments. FSc, forward scatter; SSc, side scatter. Numbers indicate percentages. C: d7EB cells lose their protective effect against CLP-induced death in the absence of CD11b+ cells. CD11b+ cells were depleted using gadolinium chloride, anti-Gr1, and anti-NK1.1 antibodies administered i.v. 24 hours before CLP induction. CD11b-depleted hosts succumbed quickly to sepsis without improvement after d7EB cell transplantation. N = 15 in each group. D: Co-culture of d7EB cells with CD11b+ lung cells reduces production of inflammatory cytokines. Lung CD11b+ cells from septic mice were co-cultured with d7EB cells (ratio, 5:1) either directly or separated by a 0.4-μm pore size Transwell filter. Non–co-cultured CD11b+ mouse cells from septic mice were used as controls. The cells were stimulated with LPS, 1 mg/ml, for 6 hours, and supernatant was collected for cytokine measurement using an ELISA specific for mouse cytokines. Directly co-cultured cells demonstrated a decrease in TNF-α and IFN-γ production, whereas production of these cytokines was not significantly different from that in controls when the cells were separated using Transwell filters. N = 3 experiments. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM.

Whether d7EB transplantation alone influenced the CD11b+ cells by affecting the composition of the CD11b+ cell population isolated from lungs of septic mice undergoing d7EB transplantation was addressed. No significant difference was observed in the number of monocytes (F4/80-positive), polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Gr-1–positive), and natural killer cells (NK1.1-positive) in the CD11b+ populations of the d7EB recipient and control lungs (Figure 4B).

To examine whether cell-cell interaction mediated the lung protection induced by d7EB cell transplantation, studies were performed in mice depleted of macrophage and monocyte populations using GdCl3 in combination with anti-Gr1 and anti-NK1.1 antibodies injected i.v. 24 hours before CLP challenge. Mortality was higher in these mice after CLP, which could not be prevented by d7EB cell transplantation (Figure 4C). Thus, d7EB cell interaction with macrophage or monocytic cells is important in the mechanism of protection.

To address whether direct interaction of mouse CD11b+ cells with d7EB cells was required for the shift to anti-inflammatory lung cytokine profile observed in mice in the cell transplantation group, lung CD11b+ cells were isolated from septic mice 12 hours after CLP and co-cultured with d7EB cells either directly or indirectly via separation using a 0.4-μL Transwell microporous filter. Both direct and indirect co-cultures were stimulated with LPS for 6 hours, and the supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α and IFN-γ production using a mouse-specific ELISA. Only direct co-culture reduced TNF-α and IFN-γ production by the CD11b+ cells (Figure 4D).

Interaction of d7EB Cells with Septic Lung CD11b+ Cells Reduces NO Production

The observation that direct interaction of d7EB and CD11b+ cells was required for the anti-inflammatory phenotype of CD11b+ cells led to consideration of the involvement of NO, an important inflammatory mediator of sepsis,25 in the response. A time course study of NO production in cultured d7EBs over 6 hours demonstrated that d7EB cells constitutively produced NO and that they also strongly expressed eNOS (Figure 5, A and B).

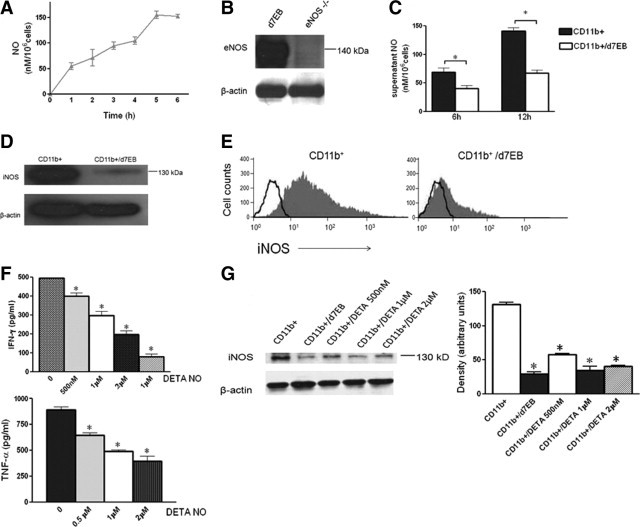

Figure 5.

Interaction of d7EB progenitor cells with CD11b+ cells decreases iNOS-derived NO production by CD11b+ cells. A: NO production by d7EB cells. d7EB cells (1 × 106) in 1 ml of medium were placed per well of a 12-well plate and stimulated or not with LPS, 1 μg/ml. NO was measured (see Methods) in the collected supernatant at the indicated times. Results are representative of 3 similar experiments. Error bars represent SEM. B: d7EB cells express eNOS. Western blot for eNOS protein in cell lysates from human d7EB cells. The specificity of the depicted band is compared with lysates from eNOS knockout mouse splenocytes. Blot is representative of 3 separate experiments. C: NO was measured (see Methods) in supernatants of directly co-cultured human d7EB and mouse CD11b+ cells (ratio, 1:5) isolated from septic mice. The co-cultured cells were stimulated with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for either 6 or 12 hours. At both times, NO production was significantly lower in the co-cultured wells compared with CD11b+ cells alone. N = 3 for each experiment. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM. D: Decreased iNOS expression in CD11b+ cells co-cultured with human d7EB cells. After 12 hours of co-culture, CD11b+ cells were selected using CD11b magnetic beads, and lysed. Western blot for iNOS protein was performed. Blot is representative of 3 separate experiments. E: Decreased intracellular iNOS expression in CD11b+ cells isolated from lungs of mice transplanted or not with d7EB cells 12 hours after CLP. CD11b+ cells were selected using magnetic beads, and permeabilized for intracellular staining for iNOS. Plot representative of 3 separate experiments. Open lines represent isotype-matched control. F: Exposure of CD11b+ cells to NO alters subsequent inflammatory profile. CD11b+ cells isolated from septic mice were stimulated with LPS, 1 mg/ml, and the indicated amounts of the NO donor diethylenetriamine NONOate (DETA NO) for 12 hours. Supernatants were collected, and TNF-α and IFN-γ concentrations were measured using an ELISA. N = 3 for each experiment. *P < 0.05 for each DETA NO concentration compared with 0; error bars represent SEM. G: Western blot for iNOS from lysates of CD11b+ cells stimulated with LPS, 1 mg/ml, and the indicated amounts of NO donor diethylenetriamine NONOate (DETA NO) for 12 hours. Density measurements of three western blots are quantified in the bar graph. *P < 0.05 for each condition compared with CD11b+ cells cultured without NO donor or d7EB cells; error bars represent SEM.

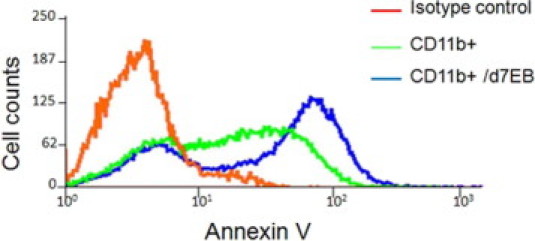

Evidence suggests that NO supplementation in the form of NO donors exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in animal models of endotoxemia through inhibition of nuclear factor κB activation and iNOS expression, and decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines.26,27 Therefore, whether the NO-producing d7EB cells exerted a similar anti-inflammatory effect on CD11b+ cells was determined. d7EBs were co-cultured with CD11b+ cells, and nitrite concentration was measured in the supernatant after LPS stimulation. Supernatant NO concentrations at 6 and 12 hours after LPS stimulation of co-cultured d7EB and CD11b+ cells were significantly lower than the supernatant NO concentration from CD11b+ cells alone (Figure 5C). This effect could not be attributed to increased apoptosis because apoptosis was not significantly different in the co-cultured CD11b+ cells compared with the CD11b+ cells cultured alone (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajpamjpathol.org). Analysis of iNOS expression in co-cultured CD11b+ cells showed decreased protein expression in LPS-stimulated CD11b+ cells interacting with d7EB cells (Figure 5D). This finding was supported by measurement of iNOS expression in CD11b+ cells isolated from the lungs of septic mice 12 hours after CLP, where decreased expression of the enzyme was again observed (Figure 5E). To further test the hypothesis that NO production by d7EB cells contributes to the anti-inflammatory phenotype of the mouse CD11b+ cells, an NO donor (DETA NONOate) was added directly to LPS-stimulated CD11b+ cells, this time without d7EB cells, at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2 μmol/L, and cytokine concentrations in the supernatant were measured. Reduction in TNF-α and IFN-γ production by the LPS-stimulated CD11b+ cells was observed (Figure 5F). In addition, iNOS expression in these cells after stimulation with LPS was reduced to levels comparable to those observed after co-stimulation with human d7EB cells (Figure 5G).

ACE Expression Defines the d7EB Cell Population Responsible for Dampening CD11b+ Cell Activation

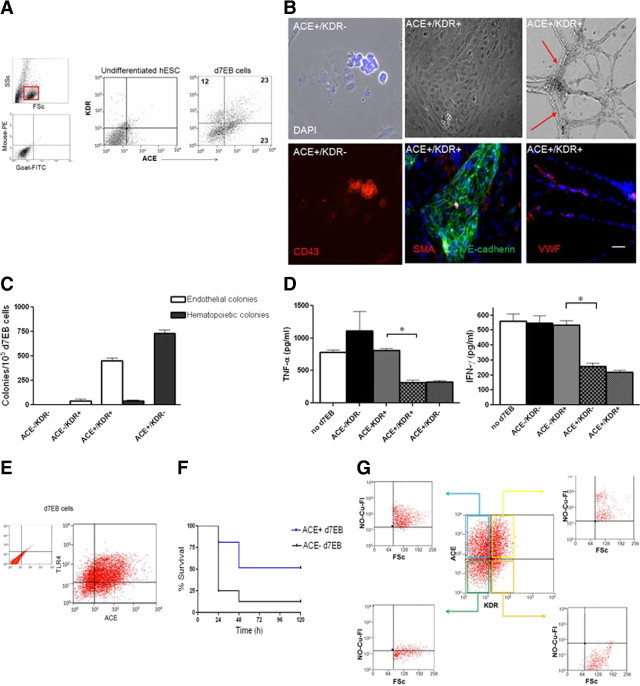

ACE and KDR expression in d7EB cells was monitored because these markers are associated with differentiation of hematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells.12,28 Neither ACE nor KDR were expressed in undifferentiated stem cells; however, increased cell surface expression of these markers was observed after onset of mesodermal differentiation, starting at day 3 and reaching maximum at day 7 to 8 when 23% of d7EB cells were ACE+KDR+ and 23% were ACE+KDR− (Figure 6A). To determine whether these two markers identified distinct lineages of mesodermally differentiated cells, FACS-fractionated d7EB cells were subcultured based on their expression of either ACE or KDR. After 4 days in subculture, ACE+KDR+ cells gave rise to endothelial cell colonies with a characteristic architecture and positive staining for VE-cadherin and von Willebrand factor. When these cells were cultured in a two-dimensional Matrigel system (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), they gave rise to lumen-containing tubes. The ACE+KDR− cells gave rise to colonies of hematopoietic precursors that stained positive for hematopoietic markers such as CD43 (Figure 6B). The endothelial and hematopoietic colony-forming capacity of the FACS-sorted cells was quantified by counting the number and types of colonies formed per 10,000 ACE+/KDR+, ACE+/KDR−, ACE−/KDR−, and ACE−/KDR+ cells. Endothelial colonies were formed almost exclusively by the ACE+/KDR+ fraction, with a small contribution from the ACE−/KDR+ cells, whereas the ACE+/KDR− fraction showed great efficiency in production of hematopoietic colonies (Figure 6C). To determine the importance of ACE and KDR markers in the observed protective phenotype against sepsis, fractionated d7EB cells were co-cultured according to their expression of ACE and KDR with the CD11b+ cells from septic mice as described above. The co-cultured cell fractions were stimulated in vitro with LPS for 12 hours, and mouse TNF-α and IFN-γ production was monitored. Both the ACE+/KDR− fraction and the ACE+/KDR+ fraction significantly reduced TNF-α and IFN-γ production (Figure 6D), indicating the critical role of the progenitor cells expressing only ACE in reducing TNF-α and IFN-γ production by CD11b+ cells. In addition, a strong cell surface co-expression of ACE and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) was observed in d7EB cells, suggesting an association between ACE expression and the capability to respond to LPS (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Cell surface marker ACE defines the subpopulation of protective d7EB progenitor cells responsible for the anti-inflammatory effect. A: FACS analysis of d7EB cells for the cell surface markers ACE and KDR identified the following cell populations: ACE+/KDR+ (23% of total) and ACE+/KDR− (23%). These cells were subsequently characterized and used for transplantation. Numbers indicate percentages. Undifferentiated human ES cells did not express either ACE or KDR. Upper small panel, gate used for cell analysis is depicted in red inset. Lower small panel, Isotype controls for ACE and KDR antibodies. B: ACE+/KDR− cell fraction gave rise to hematopoietic and endothelial colonies. Upper panels from left to right, Characteristic architecture of hematopoietic colony arising from ACE+/KDR− cells; characteristic architecture of endothelial colony arising from ACE+/KDR+ cells; ACE+/KDR+ cells are capable of forming lumen-containing tubes in 2-dimensional Matrigel. Lower panels from left to right, Hematopoietic colony staining positive for CD43; endothelial colony staining positive for VE-cadherin; endothelial colony staining positive for von Willebrand factor. Arrows indicate lumen. Scale bar = 150 mm. C: Quantification of colony efficiency of human d7EB cells. d7EB cells were fractionated as described, based on ACE and KDR expression, and subcultured. The number of endothelial and hematopoietic colonies with the previously shown architecture and phenotype was quantified. The ACE+/KDR+ fraction gave rise to 450 ± 50 endothelial colonies per 105 d7EB cells and 40 ± 10 hematopoietic colonies, whereas the ACE+/KDR− fraction gave rise exclusively to 730 ± 60.8 hematopoietic colonies. Error bars represent SEM. D: ACE+ and ACE+/KDR+ cells decreased TNF-α and IFN-γ production by mouse CD11b+ cells. d7EB cells were fractionated by FACS according to their expression of ACE and KDR, and placed in direct co-cultures with mouse CD11b+ cells (ratio, 1:5). The co-cultured cells were stimulated with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for 12 hours, and culture supernatants were collected for cytokine measurement using an ELISA. N = 3 for each experiment. *P < 0.05; error bars represent SEM. E: ACE is co-expressed withTLR4 in d7EB cells. Cell surface co-expression of ACE withTLR4 was determined via FACS using human-specific anti-TLR4 antibody. Fifty percent of ACE+ cells co-expressed TLR4. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times. F: ACE+ d7EB fraction significantly improved survival after CLP. ACE+ cells were injected i.v. (300,000 cells in 200 μL of PBS) 1 hour after CLP. At the end of 120 hours of observation, survival in the control group receiving an equal number of ACE− d7EB cells was 10% versus 50% in the ACE+ d7EB recipient group. N = 20 in each group. P < 0.0001 using a log-rank test. G: Only ACE+ cells produce NO. d7EB cells were stimulated in vitro with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for 1 hour, and subsequently stained for ACE and /KDR and intracellular NO. Of the four ACE- and KDR-based fractions of d7EB cells, only the ACE+/KDR+ and the ACE+/KDR− fractions produced NO, with more than 90% of the total cells in each fraction being positive, whereas no ACE− fractions exhibited any significant NO production. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times. FSc. forward scatter.

To further validate these observations, the ACE+ cells were fractionated and used for survival studies comparing them with the ACE− fraction. Only ACE+ d7EB cells reproduced the protective effect of the mixed d7EB population in survival against sepsis, whereas ACE− cells were not protective (Figure 6F). To examine whether the reduced production of cytokines was associated with differential NO production by the ACE+ progenitor cells, flow cytometry was used to determine co-expression of ACE and KDR with NO production. NO was produced only by the ACE-expressing cells, both ACE+/KDR+ and ACE+/KDR−, whereas ACE− cells did not produce NO (Figure 6G).

Discussion

hESCs, derived from the inner cell mass of the pre-implantation blastocyst, are defined by their ability to self-renew and to differentiate into all types of mature cells.29,30 Although these cells and their derivatives in different stages of differentiation have been used for cell therapy applications in animal models of cardiovascular disease,31–33 peripheral vascular disease,12,34 and central nervous system disorders,21,22,35,36 their potential in preventing sepsis-induced lung inflammatory injury characteristic of adult respiratory distress syndrome has not been addressed. The present study demonstrates for the first time the role of a population of progenitor cells derived from hESCs in preventing lung inflammatory injury induced by sepsis and improving survival in mice. The results show that the protection is the result of the subset of cells that are ACE+ to respond to LPS by producing eNOS-derived NO. These cells functioned by moderating the pro-inflammatory cytokine production of the host immune CD11b+ cells and reducing the high output of iNOS-derived NO cells and thereby mitigating lung inflammatory injury.

The protective effects of hESC-derived progenitor cells were associated with decreased production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ and maintenance of the production of the major anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. It was demonstrated that protection by hESC-derived progenitor cells was the result of the interaction of these cells with resident lung CD11b+ cells. Direct interaction of hESC-derived progenitor cells with CD11b+ cells was required to create the anti-inflammatory environment in lungs because neither injection of septic mice with d7EB-conditioned medium nor indirect co-cultures reproduced the salutary changes in the cytokine profile.

Because of the need for cell-cell interaction, the possibility was considered that paracrine factors with sufficient diffusing capacity and instability in solution such as NO37 might be involved. d7EB progenitor cells constitutively produced eNOS-derived NO in amounts comparable to those of immune cells, and strongly expressed eNOS. Co-culturing CD11b+ cells with d7EB cells significantly reduced NO production in the culture supernatant after stimulation with LPS. This reduction in NO production was coupled with inhibition of iNOS expression in the co-cultured CD11b+ cells and in CD11b+ cells isolated from lungs of septic mice that received transplanted d7EB cells.

eNOS-derived NO is beneficial in maintaining vascular endothelial integrity,38 and eNOS-derived NO production suppresses nuclear factor κB activity, decreases the transcription of iNOS and intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and prevents lung injury and death due to endotoxin.39 Thus, NO produced by d7EB cells may protect against iNOS activation and resultant high NO production, which has known deleterious effects on the host.40 To test this hypothesis, CD11b+ cells were exposed to an NO donor at a concentration range that induces NO release equivalent to the amount of NO produced by d7EB cells. This experiment reproduced the decreased generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduced the iNOS expression observed in the CD11b+ cells co-cultured with human d7EB cells. Thus, the results suggest a critical role of eNOS-derived NO by d7EB cells in down-regulating iNOS activation in CD11b+ cells and, thereby, dampening the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

These studies provide a mechanistic basis by which d7EB cells prevent sepsis-induced lung inflammatory injury. hESC-derived d7EB cells responsible for the protective phenotype were identified and found to be enriched in two cell surface markers, ACE and KDR. It was also demonstrated that the population consisting of ACE+KDR+ and ACE+KDR− progenitor cells gave rise in culture to endothelial and hematopoietic colonies, respectively. In addition, the ACE-expressing cells expressed TLR4, the receptor sensing LPS, and produced NO. In contrast, ACE− cells did not exhibit these characteristics. The functional importance of these observations was reinforced by the ability of ACE+ fractions of d7EB cells to modulate the inflammatory cytokine production profile of CD11b+ host cells through direct cell-cell interaction. ACE is constitutively expressed on the surface of endothelial and hematopoietic precursors,41,42 and ACE has been identified as a marker of hematopoietic stem cells present at all stages in the ontogeny of the human hematopoietic system43 and as a novel marker of hemangioblasts differentiating from hESCs.28 Evidence also points to an important role of ACE in sepsis. ACE knockout mice exhibited improved lung injury scores after acid aspiration, endotoxin challenge, and peritoneal sepsis.44 Cohort studies in humans have shown a correlation between ACE polymorphisms and susceptibility to and death from adult respiratory distress syndrome,45 and decreased plasma concentrations of ACE have been observed in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome and sepsis.46 A close homologue of ACE, ACE 2, has been identified as a key factor in protection from adult respiratory distress syndrome, and it also functions as a critical in vivo receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome.47,48

A limitation of the present study is that the immunologic properties of human progenitor cells were studied in a xenograft model, introducing biases related to cross-species barriers. However, there is no reason to believe that species incompatibility affects the validity of the proposed mechanism, which involves interaction with host CD11b+ cells and modulation of NO production. Human cells were not acutely eliminated by the immune-competent mice because cells were detected in lungs for 24 hours after injection. These data are in accord with observations in syngeneic mouse mesenchymal stem cells6 and may be related to the immunosuppressive nature of the human cells.49 It is likely, however, that some degree of immunosuppression will be required for longer term xenotransplantation studies.50

Although, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to describe the function of mesodermally differentiated hESCs in a model of lethal sepsis and lung injury, other studies have used bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in similar models.4,6–11 These studies demonstrated an anti-inflammatory benefit of these cells but showed variable effects on the production of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines. In a polymicrobial sepsis model, the beneficial effect of bone marrow stem cells was attributed to stem cell–induced production of IL-10 by host macrophages,6 sphingosine-1-phosphate production by stem cells,11 and homing of stem cells to lungs through integrin expression.7,11 hESC-derived progenitor cells represent a much earlier developmental stage than bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, and they have demonstrated ability to differentiate into niche-specific mature cells, a characteristic that distinguishes them from adult mesenchymal stromal cells. Although the importance of the interaction of hESC-derived cells with host CD11b+ cells and the association of ACE expression with the protective phenotype were observed, factors such as homing to a niche and the engraftment potential of hESC-derived cells that may also be important in the observed protection cannot be ruled out. Findings of the present study demonstrate that d7EB cells, a population of hESC-derived progenitor cells, constitute a novel immunomodulatory cell population with therapeutic potential in sepsis that may have clinical application in cell-based therapy.

Footnotes

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.09.041.

Supplementary Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Apoptosis of LPS-stimulated CD11b+ cells is not significantly affected by human d7EB cells. CD11b+ cells were directly co-cultured with human d7EB cells at a ratio of 5:1 and stimulated with LPS, 1 μg/ml, for 12 hours. Controls were CD11b+ cells not co-cultured with d7EB cells but stimulated with LPS at the same dosage. Annexin V expression was measured using flow cytometry gated in CD11b+ cells. Image is representative of 3 experiments.

References

- 1.Ware L.B., Matthay M.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zambon M., Vincent J.L. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest. 2008;133:1120–1127. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard G.R., Artigas A., Brigham K.L., Carlet J., Falke A., Hudson L., Lamy M., LeGall J.R., Morris A., Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;49:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta N., Su X., Popov B., Lee J.W., Serikov V., Matthay M.A. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179:1855–1863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mei S.H.J., McCarter S.D., Deng Y., Parker C.H., Liles W.C., Stewart D.J. Preven tion of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemeth K., Leelahavanichkul A., Yuen P.S.T., Mayer B., Parmelee A., Doi K., Robey P.G., Leelahavanichkul K., Koller B.H., Brown J.M., Hu X., Jelinek I., Star R.A., Mezey E. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E2–dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wary K.K., Vogel S.M., Garrean S., Zhao Y.D., Malik A.B. Requirement of a4b1 and a5b1 integrin expression in bone-marrow–derived progenitor cells in preventing endotoxin-induced lung vascular injury and edema in mice. Stem Cells. 2009;27:3112–3120. doi: 10.1002/stem.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J., Woods C.R., Mora A.L., Joodi R., Brigham K.L., Iyer S., Rojas M. Prevention of endotoxin-induced systemic response by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:131–141. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00431.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J., Qu J., Cao L., Sai Y., Chen C., He L., Yu L. Mesenchymal stem cell–based angiopoietin-1 gene therapy for acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Pathol. 2008;214:472–481. doi: 10.1002/path.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada M., Kubo H., Kobayashi S., Ishizawa K., Numasaki M., Ueda S., Suzuki T., Sasaki H. Bone marrow–derived progenitor cells are important for lung repair after lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 2004;172:1266–1272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y.D., Ohkawara H., Rehman J., Wary K.K., Vogel S.M., Minshall R.D., Zhao Y.Y., Malik A.B. Bone marrow progenitor cells induce endothelial adherens junction integrity by sphingosine-1-phosphate–mediated Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:696–704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu S.J., Feng Q., Caballero S., Chen Y., Moore M.A.S., Grant M.B., Lanza R. Generation of functional hemangioblasts from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4:501–509. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batiuk T.D., Urmson J., Vincent D., Yatscoff R.W., Halloran P. Quantitating immunosuppression: estimating the 50% inhibitory concentration for in vivo cyclosporine in mice. Transplantation. 1996;6:1618–1624. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199606150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rittirsch D., Huber-Lang M.S., Flierl M.A., Ward P.A. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protocols. 2009;4:31–36. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao X.P., Standiford T.J., Rahman A., Newstead M., Holland S.M., Dinauer M.C., Liu Q.H., Malik A.B. Role of NADPH oxidase in the mechanism of lung neutrophil sequestration and microvessel injury induced by gram-negative sepsis: studies in p47phox−/− and gp91phox−/− mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:3974–3982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orrington-Myers J., Gao X., Kouklis P., Broman M., Rahman A., Vogel S.M., Malik A.B. Regulation of lung neutrophil recruitment by VE-cadherin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L764–L771. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00502.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim M.H., Xu D., Lippard S.J. Visualization of nitric oxide in living cells by a copper-based fluorescent probe. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:375–380. doi: 10.1038/nchembio794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim M.H. Preparation of a copper-based fluorescent probe for nitric oxide and its use in mammalian cultured cells. Nat Protocols. 2007;2:408–415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min J.Y., Yang Y., Converso K.L., Liu L., Huang Q., Morgan J.P., Xiao Y.F. Transplantation of embryonic stem cells improves cardiac function in postinfarcted rats. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:288–296. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2002.92.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito T., Kuang J.Q., Bittira B., Al-Khaldi A., Chiu R.C. Xenotransplant cardiac chimera: immune tolerance of adult stem cells. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D.Y., Park S.H., Lee S.U., Choi D.H., Park H.W., Paek S.H., Shin H.Y., Kim E.Y., Park S.P., Lim J.H. Effect of human embryonic stem cell–derived neuronal precursor cell transplantation into the cerebral infarct model of rat with exercise. Neurosci Res. 2007;58:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song J., Lee S.T., Kang W., Park J.E., Chu K., Lee S.E., Hwang T., Chung H., Kim M. Human embryonic stem cell–derived neural precursor transplants attenuate apomorphine-induced rotational behavior in rats with unilateral quinolinic acid lesions. Neurosci Lett. 2007;423:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fändrich F., Lin X., Chai G.X., Schulze M., Ganten D., Bader M., Holle J., Huang D.S., Parwaresch R., Zavazava N., Binas B. Preimplantation-stage stem cells induce long-term allogeneic graft acceptance without supplementary host conditioning. Nat Med. 2002;8:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benimetskaya L., Loike J.D., Khaled Z., Loike G., Silverstein S.C., Cao L., el Khoury J., Cai T.Q., Stein C.A. Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) is an oligodeoxynucleo tide-binding protein. Nat Med. 1997;3:414–420. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connelly L., Jacobs A.T., Palacios-Callender M., Moncada S., Hobbs A.J. Macrophage endothelial nitric oxide synthase autoregulates cellular activation and pro-inflammatory protein expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26480–26487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anuar F., Whiteman M., Siau J.L., Kwong S.E., Bhatia M., Moore P.K. Nitric oxide releasing flurbiprofen reduces formation of proinflammatory hydrogen sulfide in lipopolysaccharide-treated rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:966–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall M., Keeble J., Moore P.K. Effect of a nitric oxide releasing derivative of paracetamol in a rat model of endotoxaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:516–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zambidis E.T., Park T.S., Yu W., Tam A., Levine M., Yuan X., Pryzhkova M., Peault B. Expression of ACE (CD143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2008;112:3601–3614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reubinoff B.E., Pera M.F., Fong C.Y., Trounson A., Bongso A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:399–404. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson J.A., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Shapiro S.S., Waknitz M.A., Swiergiel J.J., Marshall V.S., Jones J.M. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kofidis T., Lebl D.R., Swijnenburg R.J., Greeve J.M., Klima U., Gold J., Xu C., Robbins R.C. Allopurinol/uricase and ibuprofen enhance engraftment of cardiomyocyte-enriched human embryonic stem cells and improve cardiac function following myocardial injury. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laflamme M.A., Chen K.Y., Naumoval A.V., Muskheli V., Fugate J.A., Dupras S.K., Reinecke H., Xu C., Hassanipour M., Police S., O'Sullivan C., Collins L., Chen Y., Minami E., Gill E.A., Ueno S., Yuan C., Gold C., Gold J., Murry C.E. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L., Soonpaa M.H., Adler E.D., Roepke T.K., Kattman S.J., Kennedy M., Henckaert E., Bonham K., Abbott G.W., Linden M., Field L.J., Keller G.M. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR1 embryonic-stem-cell–derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho S.W., Moon S.H., Lee S.H., Kang S.W., Kim J., Lim J.M., Kim H.S., Kim B.S., Chung H.M. Improvement of postnatal neovascularization by human embryonic stem cell–derived endothelial-like cell transplantation in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Circulation. 2007;116:2409–2419. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.687038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Hur T., Idelson M., Khaner H., Pera M., Reinhartz E., Itzik A., Reubinoff B.E. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell–derived neural progenitors improves behavioral deficit in parkinsonian rats. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1246–1255. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonntag K.C., Pruszak J., Yoshizaki T., van Arensbergen J., Sanchez-Pernaute R., Isacson O. Enhanced yield of neuroepithelial precursors and midbrain-like dopaminergic neurons from human embryonic stem cells using the bone morphogenic protein antagonist noggin. Stem Cells. 2007;25:411–418. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moncada S., Higgs A. The l-arginine–nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Predescu D., Predescu S., Shimizu J., Miyawaki-Shimizu K., Malik A.B. Constitutive eNOS-derived nitric oxide is a determinant of endothelial junctional integrity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L371–L381. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00175.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrean S., Gao X.P., Brovkovych V., Shimizu J., Zhao Y.Y., Vogel S.M., Malik A.B. Caveolin-1 regulates NF-kappaB activation and lung inflammatory response to sepsis induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2006;177:4853–4860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skidgel R.A., Gao X.P., Brovkovych V., Rahman A., Jho D., Predescu S., Standiford T.J., Malik A.B. Nitric oxide stimulates macrophage inflamma tory protein-2 expression in sepsis. J Immunol. 2002;169:2093–2101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corvol P., Williams T.A., Soubrier F. Peptidyl dipeptidase A: angiotensin converting enzyme. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:283–305. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costerousse O., Allegrini J., Lopez M., Alhenc-Gelas F. Angiotensin I–converting enzyme in human circulating mononuclear cells: genetic polymorphism of expression in T-lymphocytes. Biochem J. 1993;290:33–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2900033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jokubaitis V.J., Sinka L., Driessen R., Whitty G., Haylock D.N., Bertoncello I., Smith I., Peault B., Tavian M., Simmons P.J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) marks hematopoietic stem cells in human embryonic, fetal, and adult hematopoietic tissues. Blood. 2008;111:4055–4063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imai Y., Kuba K., Rao S., Huan Y., Guo F., Guan B., Yang P., Sarao R., Wada T., Leong-Poi H., Crackower M.A., Fukamizu A., Hui C.C., Hein L., Uhlig S., Slutsky A.S., Jiang C., Penninger J.M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall R.P., Webb S., Bellingan G.J., Montgomery H.E., Chaudhari B., McAnulty R.J., Humphries S.E., Hill M.R., Laurent G.J. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is associated with susceptibility and outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:646–650. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suffredini A.E., Chanock S.J. Genetic variation and the assessent of risk in septic patients. Intens Care Med. 2006;32:1679–1680. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imai Y., Kuba K., Penninger J.M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2006–2012. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W., Bao L., Zhang B., Liu G., Wang Z., Chappell M., Liu Y., Zheng D., Leibbrandt A., Wada T., Slutsky A.S., Liu D., Qin C., Jiang C., Penninger J.M. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grinnemo K.H., Sylven C., Hovatta O., Dellgren G., Corbascio M. Immunogenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;331:67–78. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swijnenburg R.J., Schrepfer S., Govaert J.A., Cao F., Ransohoff K., Sheikh A.Y., Haddad M., Connolly A.J., Davis M.M., Robbins R.C., Wu J.C. Immunosuppressive therapy mitigates immunological rejection of human embryonic stem cell xenografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12991–12996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]