Abstract

Purpose: To analyze and evaluate the necessity and use of dynamic gating techniques for compensation of baseline shift during respiratory-gated radiation therapy of lung tumors.

Methods: Motion tracking data from 30 lung tumors over 592 treatment fractions were analyzed for baseline shift. The finite state model (FSM) was used to identify the end-of-exhale (EOE) breathing phase throughout each treatment fraction. Using duty cycle as an evaluation metric, several methods of end-of-exhale dynamic gating were compared: An a posteriori ideal gating window, a predictive trend-line-based gating window, and a predictive weighted point-based gating window. These methods were evaluated for each of several gating window types: Superior∕inferior (SI) gating, anterior∕posterior beam, lateral beam, and 3D gating.

Results: In the absence of dynamic gating techniques, SI gating gave a 39.6% duty cycle. The ideal SI gating window yielded a 41.5% duty cycle. The weight-based method of dynamic SI gating yielded a duty cycle of 36.2%. The trend-line-based method yielded a duty cycle of 34.0%.

Conclusions: Dynamic gating was not broadly beneficial due to a breakdown of the FSM’s ability to identify the EOE phase. When the EOE phase was well defined, dynamic gating showed an improvement over static-window gating.

Keywords: lung cancer, respiratory motion, respiratory gating, baseline shift

INTRODUCTION

It has been well documented that respiratory motion creates an uncertainty in the targeting of radiotherapy for lung tumors1 and that this motion can be greater than 1–5 cm,2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 though smaller in medial and apical tumors.8 This uncertainty brings about a need for larger treatment margins in conventional radiation therapy,6 usually 1–2 cm (Refs. 9, 10) and as high has 3.1 cm.11 Respiratory gating is an advanced image guided radiation treatment approach to compensate tumor motion induced by patient respiration. The beam is on only when the tumor is in a certain predefined region, i.e., the gating window. Gating has been in use since the late 1980s.12, 13 Its primary application is for lung cancer, but applications have included liver7 and breast cancer.14 Previous studies have shown that respiratory gating can reduce treatment margin up to 36% in the superior∕inferior (SI) direction, giving margins as small as 3 mm.4, 11, 15, 16, 17 However, respiratory gating increases the total treatment time of a patient.18

Based on gating window determination, there are two common gating approaches: Phase-based gating and amplitude gating. In phase-based gating, the gating window is set to be some percent of the breathing cycle, effectively fixing the duty cycle.19 In amplitude-based gating, the window is a fixed width about some window center corresponding to tumor motion in the SI, lateral (LAT), and∕or anterior∕posterior (AP) directions.18, 19, 20, 21 Studies have been done with gating windows ranging from 2.5 to 12.5 mm wide18 and by defining the window based on displacement percentiles.21 One study showed little difference between phase-based and amplitude-based gating.19 Gating windows are often defined about the most extreme positions in the breathing cycle:9 The end-of-exhalation (EOE) and the end-of-inhalation (EOI). EOE is chosen more often7, 10, 15, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24 and is more effective4 because EOE has longer duration and slower tumor motion.8, 9, 16, 25 In addition, the position of the EOE window is more reproducible.3, 19, 20, 25, 26 EOI gating is often used with a breath-hold technique (deep-inspiration breath-hold) to increase reproducibility and stability.5, 26, 27 EOI gating has the advantage of lower lung toxicity to surrounding normal tissue than EOE gating;2, 8, 9, 19, 25, 26 however, EOI gating has more residual motion than EOE gating.19

One metric for evaluating respiratory gating is the duty cycle, which is the fraction of total treatment time during which radiation is being delivered. In fixed-duty cycle experiments, the efficacy of duty cycles ranging from 20% to 50% have been studied.1, 9, 11, 15, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28 In experiments with fixed gating windows, duty cycles ranging from 12.2% to 69% have been seen.4, 7, 8, 17, 20 Various studies have sought to improve the performance of respiratory gating by providing audio or visual coaching to patients so as to increase the reproducibility and stability of their breathing patterns, especially while the tumor is in the gating window.3, 7, 9 It has been found that EOI gating with audio coaching is equivalent to EOE gating when both techniques have a fixed 30% duty cycle.19

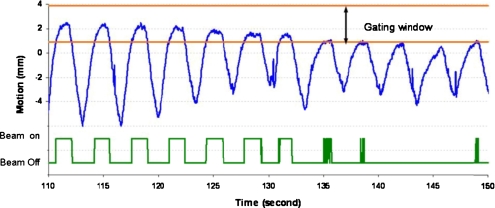

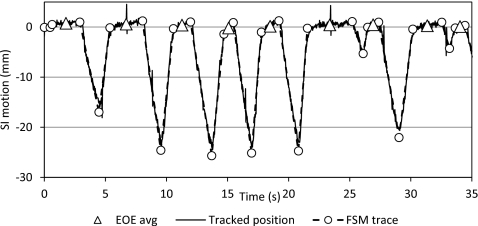

Respiratory motion is patient-specific and there are changes over time in motion amplitude, respiratory period, and baseline location from one breathing cycle to another. In addition, there is noise signal, including random spike noise generated from the tracking system and noise from cardiac motion.29 Figure 1 illustrates the superior-inferior motion trace of a lung tumor tracked based on an internal implanted fiducial marker. Phase-based gating is vulnerable to duty cycle fluctuations and amplitude variation, which will decrease the effectiveness of the treatment and potentially increase false beam on time, such as during 135–150 s in Fig. 1. In a phase-based gating scenario, the beam will be on even though the tumor is not in the gating window. The amplitude-based gating can detect the motion changes; however, the gating duty cycle will be low and will result in much longer treatment time, especially with baseline shift, as demonstrated in Fig. 1. In addition, noise in the motion signal can cause frequent beam toggling, especially if the gating window is not appropriately set, as shown in the latter portion of Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Fixed amplitude-based gating window for tumor motion with baseline shift and the corresponding beam on/off signal over time.

It has been recommended to account for baseline shift when respiratory gating, i.e., a dynamic window center.14 However, only limited work has been done to improve duty cycles by adjusting the gating window.20 In this work, we present several methods of dynamic gating for real-time baseline shift compensation and an analysis of their efficacy.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Materials

This study used the 3D motion of implanted gold fiducials in 30 lung tumors during 592 radiotherapy fractions tracked using real-time fluoroscopy at a rate of 30 Hz by Hokkaido University.30 Tumor fiducials were tracked with four orthogonal fluoroscopes during individual treatment fractions, generating tuples of the form (t,x,y,z), where x is LAT position, y is SI position, and z is AP position. The average amplitude of tumor motion for each treatment fraction in three dimensions was 13.9 mm (σ=8.2) and the average baseline drift was 6.6 mm (σ=9.2) in the LAT direction, 9.6 mm (σ=10.3) in the SI direction, and 9.1 mm (σ=11.8) in the AP direction. The tumors are considered as solid and nondeformable tumors. If only translational motion is considered, the motion trajectory represents the motion of each voxel in the tumor and the GTV motion.

Methods

Motion data preprocessing

The motion data were classified using the finite state model (FSM) developed by Wu.31 The FSM is a real-time algorithm for classifying the breathing state of a motion data point from a moving lung tumor. In the FSM, a data point is classified in one of four breathing states: Exhale, EOE, inhale, and irregular.

Gating window definition

The size of the gating window can be determined in different ways. A smaller gating window will reduce radiation dose to surrounding healthy tissue and critical structures, yet result in lower gating duty cycle, longer treatment duration, and more beam on∕off changes. A larger gating window would result in higher duty cycle, yet increased treatment margins. In practice, the gating window size is decided based on the patient-specific respiratory motion patterns and depends on motion stabilities, amplitude, tumor volume, and other information. For this study, gating window sizes of 3 and 5 mm are simulated and compared. A fixed gating window was defined as a 3 or 5 mm spatial window centered on the average tumor position during one or more complete EOE phases, as the EOE state has relative small motion. Four different gating windows were investigated.

Gating window based on SI position: The gating window was a 1.5 or 2.5 mm expansion for the 3 or 5 mm gating window, respectively, in each of the superior∕inferior directions about the average position of the tumor in the EOE phase.

Gating window based on AP beam: The gating window was a 1.5 or 2.5 mm expansion in each direction perpendicular to an AP beam, i.e., superior, inferior, right, and left.

Gating window based on LAT beam: The gating window was a 1.5 or 2.5 mm expansion in each direction perpendicular to a LAT beam, i.e., superior, inferior, anterior, and posterior.

Gating window based on 3D position: The gating window was a 1.5 or 2.5 mm expansion in each anatomic direction, i.e., superior, inferior, right, left, anterior, and posterior.

Gating window position determination

Three different methods were used to determine how to center the gating window.

The static gating window center was the average tumor position during the first three EOE phases of the treatment fraction.

The ideal gating window had gating windows determined a posteriori for each EOE phase and placed on the center of each EOE phase.

Several types of dynamic gating windows had the center of the window changed upon leaving each EOE phase.

Dynamic gating algorithms

Two methods of changing the gating window center were evaluated.

- In the weighted-center method, the average tumor position for each of the previous three EOE phases was considered as the vector triples (x1,y1,z1), (x2,y2,z2), and (x3,y3,z3). The window center was calculated as a weighted average of the vector triples

where 0≤wi≤1, w1+w2+w3=1, and w1=n⋅0.05,n∊Z20.

All combinations of w1, w2, and w3 were considered and the duty cycle for each combination was calculated for each treatment fraction. For each fraction, the weighting combinations giving the ten largest duty cycles were recorded. Three-dimensional histograms were made showing the number of times each weighting combination was considered favorable using scatter3 in MATLAB (MATLAB® The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

• In the trend-line method, the gating window center was calculated using the slope of a linear regression line fit to the average tumor position of each of several previous EOE phases. This method was evaluated considering the previous two, three, four, and five EOE phases. The window center was calculated by extending the trend-line from its calculated path. N.B.: The trend-line method for three previous EOE phases is a special case of the weighted-center method in which w1=w2=w3.

For each gating window method, the duty cycle was calculated as the fraction of total tracking time that the tumor was located within the gating window.

RESULTS

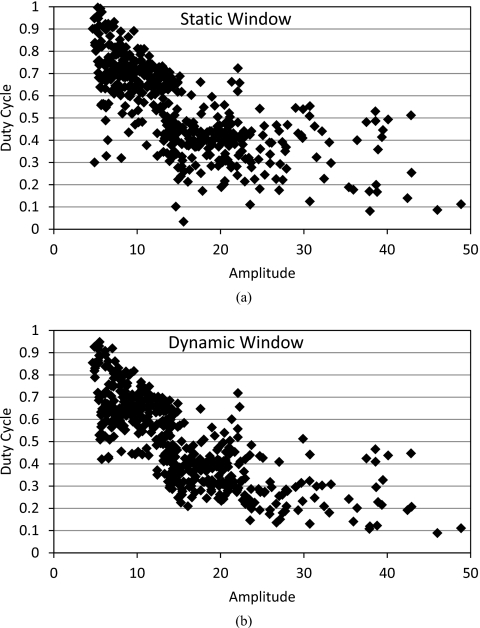

For a 3 mm gating window size, the static-window gating method gave an average duty cycle of 39.6% (σ=17.6%) for a SI gate. The ideal-window gating method gave a significantly larger average duty cycle of 41.5% (σ=16.0%) for a SI gate (p<0.001). For the 3D window, the average duty cycle improvement was 4.3% when comparing the ideal window to the static window. Similarly, this improvement was 2.6% for the AP beam and 4.0% for the LAT beam. The analysis was repeated with a 5 mm gating window, the comparative results were unchanged, with duty cycles being increased 12%–14% in all cases. The relationships between the duty cycle and the amplitude (averaged over a treatment fraction) are compared and illustrated in Fig. 2. The scattered plots showed that for fractions with small amplitude and∕or low duty cycle, there is more increase of duty cycle from static gating to dynamic gating. This effect was more pronounced with the 5 mm gating window.

Figure 2.

The relationships of duty cycle and amplitude for each fraction of (a) static gating and (b) dynamic gating, where the gating window size is 5 mm

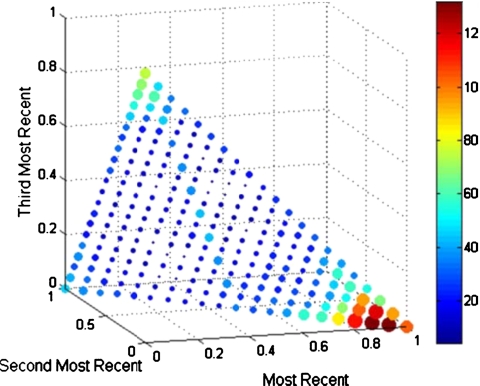

The remaining results are presented based on the 3 mm gating window. The weight-based method of dynamic gating performed best when the most recent EOE phase was given a weighting of at least 0.85 (see Fig. 3). Each fraction was evaluated for all weighting combinations in which w1 was at least 0.85. The average duty cycle for all fractions shows little variability over the set of weighting combinations for a SI window (36.0%, σ=0.3%). It was also determined how many fractions, at each weighting combination, had duty cycles greater than the static-window case. For a SI gating window, these combinations produced a higher duty cycle in 25%–28% of fractions, with the most benefit occurring with the weighting combination ⟨0.9,0.05,0.05⟩: 29%–33% of fractions saw benefits for an AP gating window, with the most benefit from ⟨0.95,0.05,0⟩; 34%–39% of fractions saw benefits for a LAT gating window, with the most benefit from ⟨0.95,0.05,0⟩; and 35%–40% of fractions saw benefits for a 3D gating window, with the most benefit from ⟨0.95,0.05,0⟩.

Figure 3.

Histogram showing favorability of weighting combinations for a gating window determined only by considering SI position. The size/color of each marker indicates the favorability of that combination. The histograms for AP, LAT, and 3D beams were similar.

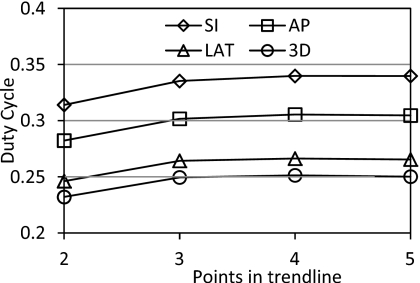

The trend-line method of dynamic gating showed increasing duty cycle with more EOE phase averages considered in the trend-line from two to four (see Fig. 4). This increase was significant when comparing four EOE phase averages in the trend-line compared to only two for all gating window types (p<0.03). Including five EOE phases gave slightly lower duty cycles when compared to four EOE phases; however, this decline was not significant (p>0.9).

Figure 4.

Average duty cycle for trend-line-based dynamic gating for each window type and number of points in the trend-line.

The results for all methods and window types are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of duty cycles for each type of gating window and method of gating. The duty cycles given for the weighted window are those for the highest performing weighting combination for each window type.

| Method | SI DC (%) | AP DC (%) | LAT DC (%) | 3D DC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static window | 39.6 | 36.0 | 31.0 | 29.3 |

| Ideal window | 41.5 | 38.6 | 35.0 | 33.6 |

| Weighted window | 36.2 | 33.3 | 29.4 | 28.1 |

| Trend-line window (n=4) | 34.0 | 30.1 | 26.6 | 25.1 |

DISCUSSION

It was somewhat unexpected that the overall performance over the 30 patients of the real-time dynamic gating methods did not outperform a static window. This led to an investigation of individual tumors and whether a particular gating method consistently produced an increase in the duty cycle during the treatment of particular tumors. The investigation found that tumor motion behavior and motion patterns have great influence on the gating duty cycle. Not all 30 tumors exhibited a significant baseline shift over time and as such, the advantage of dynamic gating did not show. In practice, it may be beneficial to consider the amplitude of tumor motion when fixing the width of the gating window.

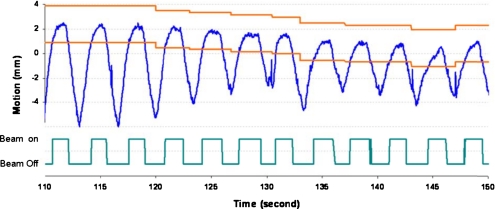

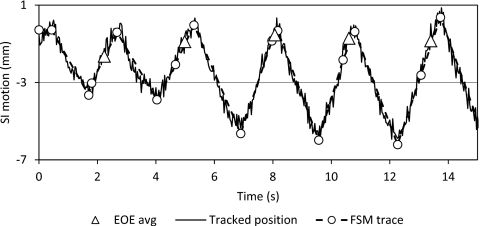

For some tumors’ motion traces, there are distinctive changes in behavior between the IN, EX, and EOE states. The FSM can easily identify the unambiguous EOE phases as they are distinct from the other breathing phases (Fig. 5). Baseline shift in these motion patterns will benefit more from dynamic gating, as shown in Fig. 6. However, for some tumors, their motion trajectories do not have a prominent EOE stage, resulting in a motion trace that consists of IN and EX states, as shown in Fig. 7. Tumors with this type of motion are not suitable for gated treatment in the first place as it will lead to low duty cycle. In addition, the EOE state of the FSM model is highly variable. The gating window position of the dynamic gating approach is inconsistent for this type motion and the duty cycle is greatly affected.

Figure 5.

Example of breathing pattern with well differentiated FSM transitions.

Figure 6.

This figure shows an amplitude-based ideal dynamic gating window being adjusted over the course of treatment.

Figure 7.

Example of breathing pattern with poorly differentiated FSM transitions.

Other than the duty cycle, several qualitative benefits were observed in the use of dynamic gating. In many of the fractions for which no duty cycle improvement was obtained, the EOE peak exited the static gating window, whereas with a dynamic window, the EOE peak was contained in the window. Two issues are masked by this apparent improvement in duty cycle. First, with the EOE peak exiting the gating window, a treatment interruption would be called for. However, this would likely be less than 2 s in duration, which is not achievable on most treatment machines. For the patient shown in Fig. 7, the instances of beam toggling are doubled for a fixed static window compared to the ideal dynamic window.

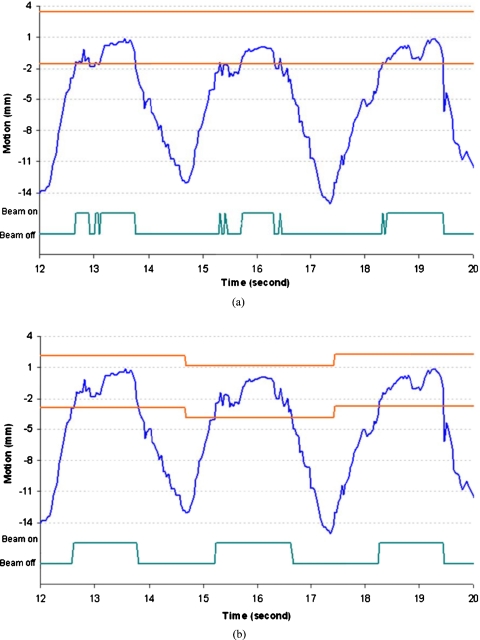

Another advantage of dynamic gating is shown in Fig. 8. The fixed gating window will require beam toggling nine times within three breathing cycles. Some of the beam toggles occur within 100 ms. The corresponding ideal dynamic window will only require three instances of beam toggling. For these three breathing cycles, the gating duty cycle changes from 34.4% to 47.7%.

Figure 8.

Comparison of static and dynamic window showing scenario in which (a) static gating window requires additional rapid beam toggling and (b) the dynamic gating window perform better with less beam toggling and increased duty cycle. The gating window size is 5 mm in these two figures.

Due to the noise in the motion signal and irregular breathing patterns, even with the ideal dynamic gating window, the amount of beam toggling is still substantial. A smoothing algorithm can be applied to avoid beam toggling caused by the noise signal. However, the beam toggling caused by irregular breathing patterns will not be solved by any smoothing algorithm. Additionally, it may be efficacious to recognize the location of the current EOE phase as it begins, rather than attempt to predict it a priori. The online FSM is able to do this with very short latency and modification of the online FSM for dynamic gating is another research direction for the presented work. At present, this is not feasible due to FSM and mechanical system latencies, meaning that by the time the EOE phase is recognized and adjustments are made, it may already be over. A compromise could be informing the predicted location with a temporally closer phase, such as the immediately prior inhalation or exhalation phase.

Moreover, an interruption of the gating signal in the EOE phase is opposite the goals of EOE-based gating. The stability of the EOE phase is the reason for choosing it as the gating window and while a larger gating window that includes parts of the inhalation and exhalation phases might give a higher duty cycle, as sometimes occurs in the case of Fig. 7, the tumor would be in continuous motion while occupying that gating window. This trade-off of increased duty cycle for an unstable target would be clinically unacceptable. This suggests that further research is needed in placing the gating window in relation to the EOE phase and breathing phase transition points in order to minimize tumor motion within the gating window.

An additional factor that must be considered with the implementation of real-time treatment adjustments is how to redirect the radiation beam. In order to change the location of the gating window, either the patient must be moved through a treatment couch adjustment, or the radiation beam must be adjusted, possibly using a dynamic multileaf collimator. A side effect of such adjustments could be that while dose to the tumor is maintained, an increase in dose to surrounding normal tissue is introduced. Patient-specific limitations and boundaries would need to be determined a priori to ensure that the dose to critical structures is acceptable and quantifiable. Potential dose to normal tissue could possibly be quantified by overlaying the treatment plan on 4DCT images showing an anticipated adjusted anatomical state, i.e., temporally near the intended treatment phase. Such research and development is beyond the scope of this article, which will be investigated more in our ongoing research.

CONCLUSION

This paper proposed a dynamic gating approach to address the baseline shift problem caused by patient respiratory motion. Two methods of determining a dynamic gating window positions have been presented and analyzed. While dynamic gating did not guarantee an increased duty cycle for every patient, certain tumor locations and breathing motion patterns can see an increased duty cycle when dynamic gating is used. With duty cycle being just one factor in evaluating the efficacy of gated treatment, future research into the dosimetric implications of dynamic gating help determine if it is an attractive option for increasing the efficiency of respiratory-gated radiation therapy. Other qualitative considerations such as decreased beam toggling and increase tumor positional stability enhance the attractiveness of dynamic gating methods and require more research to quantify.

References

- Li R., Lewis J. H., Cerviño L., and Jiang S. B., “A feasibility study of markerless fluoroscopic gating for lung cancer radiotherapy using 4DCT templates,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54, N489–N500 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/20/N03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler L. E. et al. , “Dosimetric benefits of respiratory gating: A preliminary study,” J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 5, 16–24 (2004). 10.1120/jacmp.26.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denissova S. I., Yewondwossen M. H., Andrew J. W., Hale M. E., Murphy C. H., and Purcell S. R., “A gated deep inspiration breath-hold radiation therapy technique using a linear position transducer,” J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 6, 61–70 (2005). 10.1120/jacmp.2023.25322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guckenberger M. et al. , “Potential of image-guidance, gating and real-time tracking to improve accuracy in pulmonary stereotactive body radiotherapy,” Radiother. Oncol. 91, 288–295 (2009). 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korreman S. S., Juhler-Nøttrup T., and Boyer A., “Respiratory gated-beam delivery cannot facilitate margin reduction, unless combined with respiratory correlated image guidance,” Radiother. Oncol. 86, 61–68 (2008). 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linthout N. et al. , “Treatment delivery of time optimization of respiratory gated radiation therapy by application of audio-visual feedback,” Radiother. Oncol. 91, 330–335 (2009). 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorke E., Rosenzweig K. E., Wagman R., and Mageras G. S., “Interfractional anatomic variation in patients treated with respiration-gates radiotherapy,” J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 6, 19–32 (2005). 10.1120/jacmp.2024.25334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford E. C., Mageras G. S., Yorke E., Rosenzweig K. E., Wagman R., and Ling C. C., “Evaluation of respiratory movement during gated radiotherapy using film and electronic portal imaging,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 52, 522–531 (2002). 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)02681-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead R., Featherstone C., Diffton A., Moore K., and McNee S., “The potential clinical benefit of respiratory gated radiotherapy (RGRT) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),” Radiother. Oncol. 95, 172–177 (2010). 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai A., Christensen J. D., Gore E., Khamene A., Boettiger T., and Li X. A., “Gated treatment delivery verification with on-line megavoltage fluoroscopy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 76, 1592–1598 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. et al. , “Evaluation of tumor position and PTV margins using image guidance and respiratory gating,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 76, 1578–1585 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara K. et al. , “Irradiation synchronized with respiration gate,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 17, 853–857 (1989). 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90078-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett C. G. et al. , “The effect of the respiratory cycle on mediastinal and lung dimensions in Hodgkin’s disease,” Cancer 60, 1232–1237 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korreman S. S., Pedersen A. N., Nøttrup T. J., Specht L., and Nyström H., “Breathing adapted radiotherapy for breast cancer: Comparison of free breathing gating with the breath-hold technique,” Radiother. Oncol. 76, 311–318 (2005). 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. H. et al. , “Evaluation of internal lung motion for respiratory-gated radiotherapy using MRI: Part II—Margin reduction of internal target volume,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 60, 1473–1483 (2004). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minohara S., Kanai T., Endo M., Noda K., and Kanazawa M., “Respiratory gated irradiation system for heavy-ion radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 47, 1097–103 (2000). 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00524-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underberg R. W. M., can Sörnsen de Koste J. R., Lagerwaard F. J., Vincent A., Slotman B. J., and Senan S., “A dosimetric analysis of respiration-gated radiotherapy in patients with stage III lung cancer,” Radiat. Oncol. 1, 8–8 (2006). 10.1186/1748-717X-1-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich L., Tücking T., Nill S., and Oelfke U., “Compensation for respiratory motion by gated radiotherapy: An experimental study,” Phys. Med. Biol. 50, 2405–2414 (2005). 10.1088/0031-9155/50/10/015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbeco R. I., Nishioka S., Shirato H., and Jiang S. B., “Residual motion of lung tumors in end-of-exhale respiratory gated radiotherapy based on external surrogates,” Med. Phys. 33, 4149–4156 (2006). 10.1118/1.2358197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Dy J. G., Alexander B., and Jiang S., “Fluoroscopic gating without implanted fiducial markers for lung cancer radiotherapy based on support vector machines,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, N315–N327 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/16/N01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korreman S. S. et al. , “The role of image guidance in respiratory gated radiotherapy,” Acta Oncol. 47, 1390–1396 (2008). 10.1080/02841860802282786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. et al. , “Effects of breathing variation on gating window internal target volume respiratory gated radiation therapy,” Med. Phys. 37, 3927–3934 (2010). 10.1118/1.3457329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm R. E. et al. , “Image guided respiratory gated hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (H-SBRT) for liver tumors: Initial experience,” Acta Oncol. 45, 881–889 (2006). 10.1080/02841860600919233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch N. et al. , “Evaluation of internal lung motion for respiratory-gated radiotherapy using MRI: Part I—Correlating internal lung motion with skin fiducial motion,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 60, 1459–1472 (2004). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink N. M., Chao M., Anthony J., and Xing L., “Individualized gating windows based on four-dimensional CT information for respiration-gated radiotherapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 165–175 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/1/011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. C., Chan C. L., Wong Y. W., and Cuijpers J. P., “A study on the influence of breathing phases in intensity-modulated radiotherapy of lung tumours using four-dimensional CT,” Br. J. Radiol. 83, 252–256 (2010). 10.1259/bjr/33094251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga K., Kawakami Y., Zaki M., Yamashita T., Shumizu K., and Matsunga N., “Clinical utility of co-registered respiratory-gated 99mTc-Technegas/MAA SPECT_CT images in the assessment of regional lung functional impairment in patients with lung cancer,” Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 31, 1280–90 (2004). 10.1007/s00259-004-1558-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M., Staruch R., Gladwish A., Craig J., Chen J., and Wong E., “Monte Carlo dose calculation of segmental IMRT delivery to a moving phantom using dynamic MLC and gating log files,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, N187–N196 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/10/N03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Sharp G. C., Zhao Q., Shirato H., and Jiang S. B., “Statistical analysis and correlation discovery of tumor respiratory motion,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 4761–4774 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/16/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato H., Shimizu S., Kitamura K., Nishioka T., Kagei K., Hashimoto S., Aoyama H., Kunieda T., Shinohara N., Dosaka-Akita H., and Miyasaka K., “Four-dimensional treatment planning and fluoroscopic real-time tumour tracking radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 48, 1187–1195 (2000). 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00748-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Sharp G. C., Salzberg B., Kaeli D., Shirato H., and Jiang S. B., “A finite state model for respiratory motion analysis in image guided radiation therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 5357–5372 (2004). 10.1088/0031-9155/49/23/012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]