Abstract

Scaphoid fractures are among the most common hand fractures in adults. The geometry of the scaphoid as it relates to its retrograde blood supply renders it particularly prone to avascular necrosis and other fracture complications. Though there has been long-standing debate over the optimal method of diagnosing scaphoid fractures, the best and most cost-effective methods combine clinical exam with other imaging modalities such as navicular view plain films, CT, and MRI for particularly questionable presentations. Once a scaphoid fracture is diagnosed, it should be followed by an orthopaedic surgeon and treated with cast immobilization or operative management in the case of displaced fractures. Fractures should be followed to monitor healing progress in order to ensure the eventual development of bridging bone across the fracture line, usually best appreciated on CT. Proper treatment of scaphoid fractures and assessment of fracture healing can minimize the occurrence of non-unions and associated arthritic changes.

Keywords: Scaphoid fracture, Healing, Imaging, Non-union

Introduction

Scaphoid fractures are among the most common traumatic injuries to the upper extremity and altogether account for 50–80% of carpal injuries [1]. They are most prevalent among active young adults, who fall on an outstretched hand with the wrist forced into extension (dorsiflexion) [2]. Prompt diagnosis and timely treatment decreases the occurrence of non-union of these fractures. Nevertheless, the difficulty in diagnosing such fractures using radiographic studies or clinical exam alone can sometimes allow subtle scaphoid fractures to go undiagnosed. A failure to diagnose these fractures can lead to inadequate healing, avascular necrosis, and ultimately the development of osteoarthritis and limited range of wrist motion. When accurately recognized, hand surgeons will commonly recommend minimally invasive surgery to internally stabilize this troublesome bone. Headless screw fixation can greatly reduce the frequency of non-unions and the potential for scaphoid fracture complications.

Anatomy

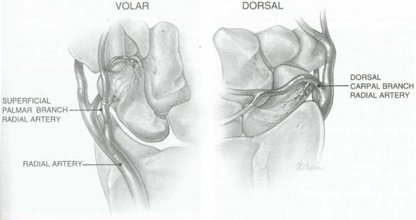

Named after the Greek word for “boat,” skaphos, the scaphoid has a unique and slightly irregular, twisted and tubular shape compared to that of other carpal bones; this has important implications for the nature of scaphoid fractures and their potential for healing. For one, the surface of the scaphoid is mostly articular and has few potential sites for vascular supply [3]. The main blood supply to the scaphoid enters through the non-articular dorsal ridge at the waist of the bone and the volar tubercle at the distal aspect of the bone (Fig. 1). A dorsal branch of the radial artery accounts for 80% of the blood supply of the scaphoid. A separate volar arterial branch to the scaphoid enters the tubercle and accounts for 20–30% of the scaphoid’s blood supply, mainly to the distal portion. The proximal pole of the scaphoid relies entirely on intramedullary blood flow. The unusual retrograde nature of the scaphoid’s blood supply renders it especially prone to non-union and proximal pole avascular necrosis [1].

Fig. 1.

Blood supply of the scaphoid. With permission from [27].

Clinical signs

Clinical examination of the wrist has traditionally been quite useful in raising suspicion or awareness to the potential for a scaphoid fracture. The main examination technique involves palpation of the anatomic snuffbox (Fig. 2a) as well as volar palpation of the distal tuberosity (Fig. 2b) [3]. Any tenderness in this region compared to the other wrist would suggest the potential for a scaphoid fracture. Snuffbox pain that can be elicited with pronation followed by gentle ulnar deviation of the wrist can also suggest a potential fracture [2].

Fig. 2.

a The snuffbox of the wrist is examined for tenderness by deeply palpating the proximal pole of the scaphoid between the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons radially and the extensor pollicis longus tendon ulnarly, just distal to the radial styloid. b The distal tubercle of the scaphoid is the volar and distal most aspect of this carpal bone and can be palpated at the radial aspect of the distal volar wrist crease at the base of the thumb

One study by Waizenegger et al. set out to elucidate whether any of the most commonly-used clinical features of scaphoid fractures could be used to include or exclude a scaphoid fracture diagnosis. The features examined in this study included a mechanism of injury involving impact against the palmar aspect of an extended hand, swelling or discoloration of the snuffbox, a positive “clamp” sign (indicated by the patient forming a clamp with the thumb and index finger of the opposite hand to hold both sides of the scaphoid area as a method of localizing the pain), and pain in the snuffbox region on palpation. Various maneuvers were also examined as clinical predictors of scaphoid fractures and included the presence of pain on ulnar or radial deviation of the wrist during forearm pronation, or a positive scaphoid shift test (in which a painful displacement is felt when forceful pressure is placed on the distal pole of the scaphoid, i.e. when moving the wrist passively from ulnar to radial deviation). This study showed that none of the clinical signs in injured wrists could serve as a reliable means of identifying a scaphoid fracture in the absence of information provided by diagnostic imaging [4]. Another study that investigated the use of clinical signs (tenderness in the anatomic snuffbox, tenderness over the scaphoid tubercle, pain on longitudinal compression of the thumb, and range of thumb movement) to evaluate a suspected scaphoid fracture found a 100% sensitivity and 74% specificity—as well as a 58% positive predictive value and 100% negative predictive value—when all four signs were used in combination within the first 24 h following injury. When used individually, range of thumb movement as a clinical indicator had only 66% sensitivity and specificity. Anatomic snuffbox tenderness, scaphoid tubercle tenderness, and pain with longitudinal compression of the thumb each had 100% sensitivity when used individually, but were much less specific with values of 19%, 30%, and 48%, respectively [5]. Thus, while no single clinical factor can be useful for diagnostic purposes, a combination of clinical signs and symptoms can certainly be of value in raising suspicion and awareness of a scaphoid fracture.

Diagnostic imaging

The three-dimensional shape of the scaphoid hinders the evaluation of fracture location and degree of fragment displacement [3]. As a result, a wide variety of imaging techniques have been used as a means to achieve maximum diagnostic value in visualizing a suspected fracture of the scaphoid.

Plain radiographs continue to be the initial imaging study of choice for suspected scaphoid fractures. However, the postero-anterior views that are typically used, even when taken with the wrist in ulnar deviation, result in an image that is distorted by the flexion and normal curvature of the scaphoid. The waist or middle third of the scaphoid is best visualized on a semi-pronated oblique view (or 45 degree posterior-anterior pronated view) as well as on lateral views [3]. Despite the widespread use of plain films to diagnose suspected scaphoid fractures, one recent study using MRI as a gold standard indicated that plain radiographs had poor sensitivity (9–49%), negative predictive value (30–40%), and reliability of follow-up when used to investigate suspected occult scaphoid fractures. That study showed follow-up radiographs taken after a normal initial radiograph to be considered an inaccurate imaging study for the diagnosis of a scaphoid fracture [6]. A separate study evaluating the use of standardized radiographs in conjunction with clinical findings demonstrated reliability in diagnosing occult fractures of the carpus and wrist, especially when these methods were performed by experienced observers. This study showed the ability of clinical and radiographic (plain film) observation to reveal occult scaphoid fractures within 38 days with high accuracy, though the failure of these methods to detect soft tissue injuries associated with the traumatic insult was a significant shortcoming [7].

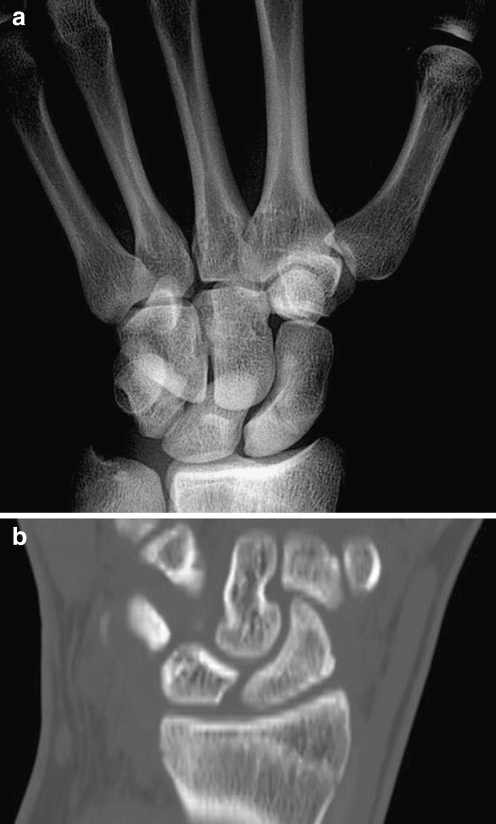

Helical CT is a technique in which x-rays are projected through the wrist while the x-ray source rotates around the patient; tomographic images are then generated from this computerized data. It is perhaps more desirable for the purpose of scaphoid fracture diagnosis in the sense that it is faster and allows for multi-planar reconstructions of the original data while also obviating the need for precise patient positioning [8]. These techniques have proven utility in ruling out scaphoid fracture displacement compared to x-rays; however CT scans have not been shown to be perfectly reliable in providing an ultimate scaphoid fracture diagnosis, with an average sensitivity of 72%, specificity of 80%, and positive predictive value of 13% [9]. Nonetheless, CT scans in the sagittal plane in conjunction with plain films (Fig. 3), can accurately detect scaphoid fractures with a high interobserver and intraobserver reliability [10].

Fig. 3.

a Plain posteroanterior radiograph with the wrist in ulnar deviation to bring the scaphoid into a profile of extension barely demonstrates a fracture line. b CT scan image of the same patient reformatted along the axis of the scaphoid more clearly reveals the fracture line

MRI is a favorable means of diagnosis primarily because it can obtain images in any plane, is sensitive to edematous changes (Fig. 4), and is free of streak artifacts than can obscure some CT examinations [8]. One study conducted by Imaeda et al. showed the potential for MRI studies to diagnose scaphoid fracture lines as early as 2 days after an injury; additionally, these lines remained visible for several months longer than the lines seen on plain films [11]. Because of cost concerns and the potential for MRI to produce false positives, current MRI use should be reserved for excluding the presence of a fracture in the setting of normal plain radiographs, normal CT scan, and positive clinical exam findings [12].

Fig. 4.

a X-ray of the wrist is completely normal on navicular view. b MRI of the same patient shows increased inflammation and edema at the scaphoid waist, indicative of a fracture

Radionuclide bone scintigraphy is another method that has been used in the evaluation of suspected scaphoid fractures. Unlike the aforementioned techniques this particular imaging study can be used to evaluate osteoblastic activity and inflammation as a means of diagnosing a scaphoid fracture [8]. Bone scans have nevertheless become less practical and are infrequently used as a form of imaging for acute fractures due to their inability to show specific fracture anatomy and location (which would necessitate further imaging, such as a CT or MRI, to localize the fracture).

Treatment

Because of the anatomic subtleties that can render the blood supply to the scaphoid rather tenuous especially following a traumatic insult, all scaphoid fractures have a risk of nonunion and should be primarily treated and followed by an orthopaedic surgeon or a hand surgeon. Scaphoid fractures can be classified into three distinct types—displaced, non-displaced, and proximal pole fractures—that vary based on severity and treatment modality. The initial emergency room management of suspected scaphoid fractures with positive or negative initial radiographs should involve immobilization in a short-arm thumb spica splint and arranged follow-up with an orthopaedic or a hand surgeon within 7–10 days, during which reexamination and repeat radiographs, as well as additional imaging such as CT or MRI, can be performed as needed. For significantly displaced fractures, an urgent consultation with an orthopaedic or a hand surgeon should be obtained [13].

Scaphoid fractures that are believed to be non-displaced first require radiographic follow-up to confirm that the fracture truly is non-displaced. If the fracture displaces, surgery is indicated to reduce the fracture and provide internal stabilization. If it remains non-displaced, cast immobilization is an accepted method of treatment, but it is falling out of favor due to the frequent need for prolonged casting. Our treatment recommendations for cast treatment (if chosen by the patient) of a nondisplaced scaphoid waist fracture consists of 4 weeks in a long arm (above elbow) thumb spica cast, followed by 6–8 weeks in a short arm (below elbow) thumb spica cast (Fig. 5a). A study comparing short and long thumb spica casts for non-displaced fractures showed a small difference favoring the above-elbow cast in order to prevent non-union of non-displaced fractures [14]. Most patients with confirmed non-displaced fractures are immobilized for 10–12 weeks; this period can be extended if union is uncertain [3]. Additional immobilization time may allow for bone consolidation which can take as long as 12–16 weeks [1].

Fig. 5.

a Short arm thumb spica cast extends from the proximal forearm to the thumb, immobilizing the wrist and the thumb ray (which extends off the distal pole of the scaphoid) to provide external stabilization of the scaphoid. b Thumb spica brace

Despite the traditional use of conservative treatment for non-displaced scaphoid fractures, recent data suggests that minimally invasive techniques using percutaneous screw fixation can lead to faster time to union than cast immobilization alone (9.2 weeks versus 13.9 weeks) [15]. Additionally, operative methods can lead to a decreased rate of non-union [15]. Two weeks after minimally invasive scaphoid fracture fixation patients are typically transitioned to a removable brace (Fig. 5b), allowing for a quicker rehabilitation and return to function compared to casting. A number of recent studies have confirmed the benefits of open reduction and internal fixation or percutaneous fixation as opposed to cast immobilization for non-displaced scaphoid fractures, especially focusing on lower nonunion rates and shorter times to return to work or sports when compared to more conservative treatment options [15–17].

Displaced fractures are treated more aggressively due to a higher rate of delayed union or non-union compared to that of non-displaced fractures. Non-operative management with cast treatment is generally not recommended. Operative reduction can be achieved with an open approach or with percutaneous techniques to preserve adjacent soft tissue structures [1]. For example, a minimally-invasive dorsal approach that leaves the dorsal ridge blood supply intact can typically be used to achieve reduction and to place a headless compression screw for rigid internal fixation. If an open reduction and structural bone grafting is indicated, a volar approach is also commonly used.

Proximal pole scaphoid fractures rarely unite with cast immobilization alone. Surgical treatment is indicated for this challenging type of scaphoid fracture, as proximal pole fractures are not only prone to nonunion, but also avascular necrosis. The use of a headless compression screw can minimize rotation and micromotion of these unstable fractures. Post-operative immobilization in a cast or brace is frequently recommended to immobilize the wrist after fixation [1].

Healing

An important component of any scaphoid fracture assessment is the determination of proper healing. The potential healing mechanisms are identical to those of fractures in general and can involve either primary or secondary healing, depending on the degree of displacement. Primary healing occurs when fracture surfaces are rigidly held in contact, allowing fracture healing to progress without the formation of a grossly visible callus [1]. In the absence of a rigid fixation at the fracture site (as can occur in displaced scaphoid fractures or fractures that are inadequately treated), secondary bone healing involving callus formation takes place. This type of healing is a continuous process involving multiple stages and can take up to a year to reach completion [18]. Though any treatment that promotes scaphoid fracture healing can be considered successful, one that promotes primary healing is clearly favorable as scaphoid fractures do not make callus and are unable to heal by secondary bone healing.

Imaging to monitor the progress of scaphoid healing is often necessary to prevent or promptly treat developing complications. Serial radiographs have typically been used to demonstrate adequate healing of scaphoid fractures but these are not without pitfalls—studies have shown poor inter-observer agreement in assessing scaphoid fracture union 12 weeks post-injury [19]. Nevertheless, radiographs remain the modality of choice to assess union, defined as “the restoration of bony architecture across the fracture site” [20]. In this respect radiographs are most commonly used to identify trabeculae crossing the fracture line or sclerosis at the fracture line.

MRIs have also proven useful in the assessment of scaphoid fracture healing. Typically the appearance of healing on MRI is seen as a “double line” representing the fracture line coupled with the revascularization front. A failure of this front to proceed is almost always associated with eventual non-union [21]. MRI is also useful in that it can confirm bony union in a high percentage of patients deemed to be clinically non-united. MRIs, unlike other imaging studies, will continue to show an abnormal signal around a stable fracture even as healing progresses to union; the only definitive sign of union is the return of normal marrow continuity across the fracture line [22]. As a result, the MRI scan is a more clinically appropriate study to identify the presence of a scaphoid fracture, rather than to determine its healing.

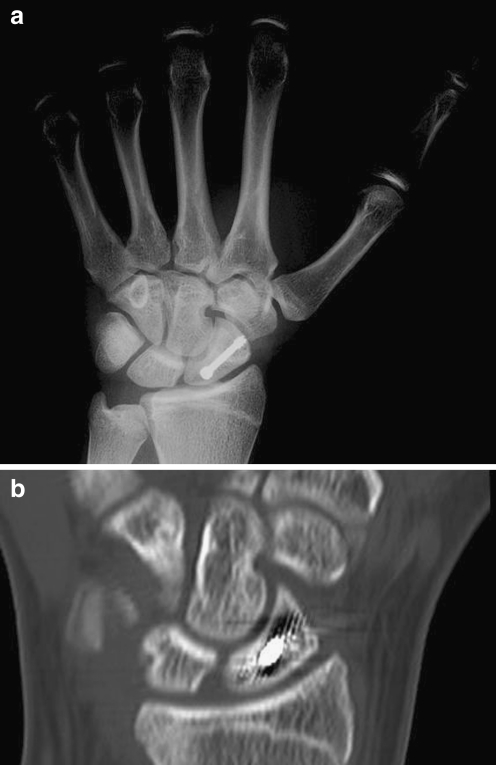

CT scans, on the other hand, can be used for the determination of scaphoid fracture healing. CT scans with reformatting in multiple planes allow for a three dimensional assessment of the trabecular architecture of the scaphoid. If there is evidence of bridging bone across the fracture site on a CT scan, then there is documented evidence of radiographic healing (Fig. 6). Most surgeons prefer to see at least 50% bridging bone prior to releasing patients to full activities. Even with radiographic healing present, it is critical that the clinical exam supports the assessment of a healed bone: the fracture site itself has become nontender and typical function has returned to the extremity.

Fig. 6.

a Plain film of a patient status post surgical treatment with scaphoid screw. b CT of same patient showing confirmed healing

Complications

The rate of scaphoid fracture complications can be quite high, especially in the wake of inadequate initial management. Delayed diagnosis and immobilization has been associated with rates of non-union up to 88% [23]. The development of scaphoid fracture non-union has significant clinical consequences; one study investigating the natural history of scaphoid non-unions showed that the vast majority resulted in degenerative changes including sclerosis or resorptive changes, radioscaphoid arthritis, or generalized arthritis of the wrist [24].

The mechanism and pathology surrounding scaphoid nonunion formation is unique to the anatomy of the scaphoid. The ability of the intercarpal and radiocarpal ligaments to stabilize the intercalated proximal carpal row is dependent on the integrity of the scaphoid. An unstable fracture of the scaphoid can in many cases allow the proximal pole of the scaphoid to rotate with the lunate. The distal pole in this situation would remain flexed (i.e. attached to the trapezium and trapezoid) resulting in an angulation through the fracture of the scaphoid that is known as a humpback deformity [3].

Aside from arthritic changes associated with scaphoid non-unions, care must be taken when treating scaphoid fractures to prevent the development of avascular necrosis of the scaphoid. This is especially seen in proximal pole fractures of the scaphoid. Avascular necrosis typically results in increasing pain and decreased range of motion of the wrist. Vascularized bone grafts are indicated to achieve maximal union rates (88%, compared to 47% union for non-vascularized structural bone grafts) [25].

The progression of a scaphoid fracture to non-union, regardless of cause, is not in itself an ultimate diagnosis of wrist collapse and arthritis; various operative techniques have been used to address this challenging orthopaedic problem. Adequate perfusion of the distal scaphoid and rigid fixation of the proximal pole can allow non-union repair and healing to proceed. These can be achieved operatively using minimally invasive or open techniques involving wrist arthroscopy, percutaneous non-union debridement, bone grafting, and internal fixation. Minimally invasive methods in the treatment of scaphoid fractures and nonunions have been shown to reduce post-operative stiffness and ultimately improve functional outcome [26].

Summary

Scaphoid fractures are a particularly challenging wrist injury, as they often manifest the identical presentation as a wrist sprain. An understanding of the relevant anatomy, clinical presentation, and radiographic findings associated with these fractures can lead to a timely diagnosis and appropriate initial treatment. Prompt management of scaphoid fractures with cast immobilization or operative reduction and internal fixation can prevent the development of devastating complications and result in an excellent functional outcome.

References

- 1.Gaebler C, McQueen MM. Carpus fractures and dislocations. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown CM, Tornetta P, editors. Fractures in adults. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 782–828. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton N. Twenty questions about scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:289–310. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90118-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ring D, Jupiter J, Herndon J. Acute fractures of the scaphoid. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:225–231. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waizenegger M, Barton N, Davis T, Wastie M. Clinical signs in scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:743–747. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parvizi J, Wayman J, Kelly P, Moran C. Combining the clinical signs improves diagnosis of scaphoid fractures. A prospective study with follow-up. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:324–327. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(98)80050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low G, Raby N. Can follow-up radiography for acute scaphoid fracture still be considered a valid investigation? Clin Radiol. 2005;60:1106–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gäbler C, Kukla C, Breitenseher M, Trattnig S, Vécsei V. Diagnosis of occult scaphoid fractures and other wrist injuries. Are repeated clinical examinations and plain radiographs still state of the art? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386:150–154. doi: 10.1007/s004230000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson D, Brandser E, Steyers C. Imaging scaphoid fractures and nonunions: familiar methods and newer trends. Iowa Orthop J. 1996;16:97–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lozano-Calderón S, Blazar P, Zurakowski D, Lee S, Ring D. Diagnosis of scaphoid fracture displacement with radiography and computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2695–2703. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temple C, Ross D, Bennett J, Garvin G, King G, Faber K. Comparison of sagittal computed tomography and plain film radiography in a scaphoid fracture model. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imaeda T, Nakamura R, Miura T, Makino N. Magnetic resonance imaging in scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:20–27. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90007-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ring D, Lozano-Calderón S. Imaging for suspected scaphoid fracture. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:954–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perron A, Brady W, Keats T, Hersh R. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: scaphoid fracture. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:310–316. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.24449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gellman H, Caputo R, Carter V, Aboulafia A, McKay M. Comparison of short and long thumb-spica casts for non-displaced fractures of the carpal scaphoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:354–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQueen M, Gelbke M, Wakefield A, Will E, Gaebler C. Percutaneous screw fixation versus conservative treatment for fractures of the waist of the scaphoid: a prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:66–71. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.9002.ebo3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papaloizos MY, Fusetti C, Christen T, et al. Minimally invasive fixation versus conservative treatment of undisplaced scaphoid fractures: a cost-effectiveness study. J Hand Surg. 2004;29B(2):116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip HSF, Wu WC, Chang RYP, et al. Percutaneous cannulated screw fixation of acute scaphoid wrist fracture. J Hand Surg. 2002;27B(1):42–46. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2001.0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sfeir C, Ho L, Doll BA, Azari K, Hollinger JO. Fracture repair. In: Lieberman JR, Friedlaender GE, editors. Bone regeneration and repair: biology and clinical applications. Totowa: Humana; 2005. pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dias J, Taylor M, Thompson J, Brenkel I, Gregg P. Radiographic signs of union of scaphoid fractures. An analysis of inter-observer agreement and reproducibility. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:299–301. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B2.3346310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dias J. Definition of union after acute fracture and surgery for fracture nonunion of the scaphoid. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:321–325. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2001.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulkarni R, Wollstein R, Tayar R, Citron N. Patterns of healing of scaphoid fractures. The importance of vascularity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:85–90. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B1.9028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNally E, Goodman R, Burge P. The role of MRI in the assessment of scaphoid fracture healing: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1926–1928. doi: 10.1007/s003300000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langhoff O, Andersen J. Consequences of late immobilization of scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13:77–79. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(88)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mack G, Bosse M, Gelberman R, Yu E. The natural history of scaphoid non-union. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merrell G, Wolfe S, Slade JF. Treatment of scaphoid nonunions: quantitative meta-analysis of the literature. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:685–691. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.34372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slade JF, Dodds S. Minimally invasive management of scaphoid nonunions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;445:108–119. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000205886.66081.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amadio PC, Moran SL. Fractures of carpal bones. In: Green DP, Pederson WC, Hotchkiss RN, Wolfe SW, editors. Green’s operative hand surgery. 5. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 711–768. [Google Scholar]