Abstract

AIM: To demonstrate the value of Diosmin (flavonidic fraction) in the management of post-haemorhoidectomic symptoms.

METHODS: Eighty-six consecutive patients with grades III and IV acute mixed hemorrhoids admitted to the Anorectal Surgical Department of First Affiliated Hospital, Xinjiang Medical University from April 2009 to April 2010, were enrolled in this study. An observer-blinded, randomized trial was conducted to compare post-haemorhoidectomic symptoms with use of Diosmin flavonidic fraction vs placebo. Eighty-six patients were randomly allocated to receive Diosmin flavonidic fraction 500 mg for 1 wk (n = 43) or placebo (n = 43). The Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy was performed by a standardized diathermy excision method. Pain, bleeding, heaviness, pruritus, wound edema and mucosal discharge were observed after surgery. The postoperative symptoms and hospitalization time were recorded.

RESULTS: The mean age of the Diosmin group and controls was 53.2 and 51.3 years, respectively. In Diosmin group, haemorrhoid piles were of the third degree in 33 patients and the fourth degree in 10; and in the control group, 29 were of the third degree and 14 were of the fourth degree. There was no statistically significance in age, gender distribution, degree and number of excised haemorrhoid piles, and the mean duration of haemorrhoidal disease between the two groups. There was a statistically significant improvement in pain, heaviness, bleeding, pruritus from baseline to the 8th week after operation (P < 0.05). Patients taking Diosmin had a shorter hospitalization stay after surgery (P < 0.05). There was also a significant improvement on the proctoscopic appearance (P < 0.001). However, there was no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of wound mucosal discharge. Two patients experienced minor bleeding at the 8th week in Diosmin group, and underwent surgery.

CONCLUSION: Diosmin is effective in alleviating postoperational symptoms of haemorrhoids. Therefore, it should be considered for the initial treatment after haemorrhoid surgery. However, further prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm the findings of this study.

Keywords: Flavonidic fraction, Postoperative complication, Haemorrhoids

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhoid is one of the most common anorectal disorders. Although haemorrhoidectomy is considered as a minor inpatient procedure, it is usually associated with significant postoperative complications, including pain, bleeding, heaviness, pruritus, mucosal discharge and anal stenosis, resulting in a protracted period of recovery. The Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy is the most widely practiced surgical approach for the management of hemorrhoids and is considered the “gold standard”. Hemorrhoids are divided into 4 stages depending on symptoms and degree of prolapse. The 3rd and 4th stages are indicated for Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy. Hemorrhoidectomy is usually associated with considerable pain, bleeding, and mucosal discharge after operation[1], which seem to be multifactorial, such as individual tolerance, mode of anesthesia, postoperative analgesics, and surgical technique[2].

Pain is a major postoperative complication after haemorhoidectomy. Although Longo’s procedure (the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids, PPH) has been widely used in recent years, it can also be confronted with the postoperative management dilemma after the procedure. A Meta-analysis comparing the PPH procedures and open haemorrhoidectomy did not show any significant differences in terms of post-operative pain. Although the postoperative bleeding and blood loss were significantly lower in the PPH group, there was no statistical difference in the aspect of other complications such as pain, pruritus, and mucosal discharge. In identifying approaches to reduce the symptoms after haemorrhoidectomy, published studies have mainly focused on the choice of surgical technique or the prevention of secondary infection in the wound[3-8]. The superiority of stapled haemorrhoidectomy in terms of less post-operative pain and quicker recovery was confirmed by a more recent systematic review of 25 randomized trials that compared stapled haemorrhoidectomy and conventional haemorrhoidectomy[9]. However, the control of hemorrhoid symptoms is not striking. Both open and closed haemorrhoidectomy have been evaluated in terms of postoperative pain. Two predominant factors responsible for post-operative pain include discomfort from the surgical wound in the sensitive anoderm as well as perianal skin and edema from tissue inflammation around the wound[10]. Alleviation of pain from the surgical incision should be achieved by minimizing tissue dissection and using different electrosurgical devices, such as diathermy, Harmonic scalpel®, and ligature™, which diminishes thermal injury to the subjacent tissues[11]. For reduction of pain from the open wound of haemorrhoidectomy, various kinds of medication, including metronidazole, glyceryl trinitrate (0.2%), steroids, local anesthetics (bupivacaine), anti-inflammatory drugs, hemorrhoid creams, are being used with variable outcome[11-13]. These studies indicated some limitations with these medications such as short duration of action and occurrence of serious side effects.

Postoperative bleeding is another important complication in haemorroids due to its frequency, which varies between 0.6% and 10%[14,15]. Post-haemorrhoidectomic bleeding is commonly associated with the passage of a hard stool. Sometimes bleeding may be alarming, because it may cause anemia very rapidly in patients. The causes of post-operative bleeding are not easily explained: in some cases it should be attributed to falling off of a scar due to electrocoagulation, whereas in other cases it is due to the lack of a thrombus, its expulsion or its dissolution, concomitant with the falling or reabsorption of the transfixed stitch.

Diosmin, flavonidic fraction, which is derived from some plants or the flavonoid Hesperidin, is promoted as a high-quality active ingredient in vein improvement supplements. Diosmin reduces inflammation and increases vein tonicity, two important factors that contribute to hemorrhoids. Researches indicate that Diosmin also appears to significantly shorten the duration of haemorrhoid bleeding as well as reduce the postoperative pain[16]. A 2000 Italian study of 66 haemorrhoid patients reported that Diosmin decreased pain by 79% and bleeding by 67% during the first week of treatment, followed by an astonishing 98% and 86% reduction in these symptoms by the second week[17]. After haemorrhoid surgery, flavonoids were found to relieve pain, bleeding and other symptoms more rapidly than standard antibiotic/anti-inflammatory treatment alone, with especially significant symptom relief during the first 3 d after surgery[18].

This study was designed to evaluate the influence of Diosmin on reducing postoperative pain, bleeding, heaviness, pruritus, and mucosal discharge after the Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy in a randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

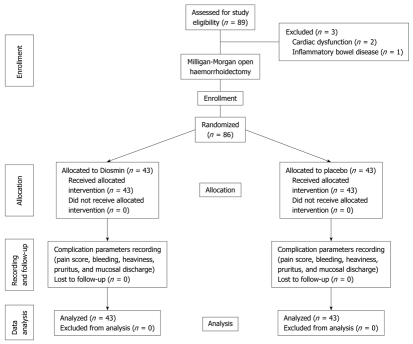

Protocol synopsis for this trial and supporting CONSORT checklist were used as supporting information (Figure 1). Diosmin clinical trial was a phase II randomized, prospective, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of Diosmin trial.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Patients aged 12-75 years with an indication for haemorrhoidectomy were eligible for the study, provided that they met the following inclusion criteria: symptomatic and prolapsing hemorrhoids Grade III or IV and informed consent. Patients complicated with fistula or anal fissure, inflammatory bowel disease, dermatitis, proctitis, pregnancy or severe cardiovascular state or pulmonary complication were excluded from the study.

Patients

The study was conducted using a computer-randomized design. A total of 86 consecutive patients with the grades III and IV acute mixed hemorrhoids admitted to Anorectal Surgical Department of First Affiliated Hospital, Xinjiang Medical University from April 2009 to April 2010, were enrolled in this study. Demographic data (age and gender), disease grades, preoperative constipation status, mean duration of disease, operating time and number of resected piles were recorded for each patient. There were no statistical differences between the two groups in these aspects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data in Diosmin and control groups

| Diosmin group1 (n = 43) | Control group2 (n = 43) | P value | |

| Mean age( yr) | 53.2 (11.2) | 51.3 (10.4) | 0.6332 |

| Male/female ratio | 26/17 | 24/19 | 0.6620 |

| No. of resected hemorrhoids | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0.1522 |

| Grades III/IV hemorrhoids | 33/10 | 29/14 | 0.9247 |

| Mean duration of hemorrhoidal disease (mo) | 21.6 (12.6) | 22.8 (14.5) | 0.6821 |

| Operating time (min) | 15.8 (1.9) | 16.9 (1.5) | 0.1295 |

| No. of constipation | 28 | 26 | 0.8235 |

Patients treated with Diosmin;

Patients treated with placebo drug.

Medical and research ethics

The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki[19], the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for Trials on Pharmaceutical Products[20]. The study protocol was approved by China governmental law and local regulations of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. This study was also conducted according to a protocol approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients or their relatives before the trial. The whole study consisted of two periods of observation (4 wk for each period). The last visit should be terminated in 90 d after operation.

Formal written informed consent was obtained from each patient after the preliminary assessment of patient’s detailed history of the disease and general and systemic examination. The patients were subjected to a few baseline investigations (haemoglobin, bleeding time, clotting time, urine complete examination). They were randomly subjected to Diosmin or placebo depending on their choice, after discussing the advantages and disadvantages of both drugs with them. The study was “blind” and the observers evaluating the complication symptom parameters were unaware of the individual treatment schedules. Blinding and coding of the drugs were done by an independent monitor who was not an investigator after repacking the look-alike capsules by a pharmaceutical company in Xinjiang. The codes were broken only after completion of the study.

Surgery

Two fixed anorectal surgeons performed all the procedures with the patient in the supine lithotomy position or jackknife position. All patients underwent proctoscopy in order to exclude other diseases in the rectum before surgery. The operations were carried out under spinal anesthesia with 15 mL bupivacaine with 1:200 000 adrenalines. Further 5 mL of the same solution was used to dissect the haemorrhoidal nodules from the internal sphincter. Except 3 patients, who had a considerable rectal mucosal prolapse and were treated with stapled haemorrhoidopexy, all the patients underwent the standard Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy.

We removed the haemorrhoidal nodule using an upside-down V-shaped incision on the anal dermis, without widening the surgical wound while approaching the sphincters. This was done in order to maintain ample mucous membrane bridges. Possible secondary nodules were removed through submucosa. Ligature of the vascular pedicle was performed clear of the internal sphincter. The extent of surgical incision was tailored according to the number of haemorrhoidal complexes. Hemorrhoids were excised to the anorectal junction or dentate line. The intervening skin and anoderm bridges were preserved adequately. Coagulation with electrotome on the anal sphincters was avoided for all patients. The edges of the residual surgical wound have to be as sharp as possible. No packs were left in the anus postoperatively. After operation, patients in both groups were prescribed fiber supplements and naproxen sodium 550 mg tablets or intramuscular pethidine (1 mg/kg body weight) as required. All patients were also advised to gently shower their perianal wounds with lukewarm water twice daily, and after bowel movements. The data concerning the complications were compared between the two groups of patients. No antibiotic prophylaxis or any kind of analgesics has ever been administered.

Randomization

Computer-based sequential method was used for the randomization at the completion of surgery into one of the two groups. This computer generated random codes used for envelopes containing the information “Diosmin” or “Placebo”. These envelopes were prepared by a statistician who was not involved the patient’s treatment or other work specific to the study. The computer randomization was completed in the Medical Statistical Center of Xinjiang Medical University.

Diosmin treatment

All patients were routinely discharged on the first postoperative day unless otherwise clinically indicated. Eighty-six patients each were either given Diosmin 500 mg or received placebo medication according to the computer-randomized result. Diosmin 500 mg was given at a dose of 3 tablets twice daily, after meals, for 3 d followed by 2 tablets twice daily from day 4 to day 7. Each complication symptom was recorded at hours 6 and 12 and on days 1, 2, 7 and 14 after operation. On the 7th day, the symptoms and any relief were recorded and the dose was further reduced to one tablet twice daily for the next 15 d. Consequent follow-ups were made on days 15, 30 and 90.

Assessment of postoperative symptoms

The Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy was performed by a standardized diathermy excision method. Diosmin was started on the 6th day after surgery. A standardized questionnaire was completed which included postoperative information about pain, bleeding, heaviness, pruritus, wound edema and mucosal discharge. The evolution of these symptoms during the postoperative period was assessed by means of patient’s self-questionnaires. Two predominant observatory parameters were postoperative pain and bleeding. Pain was assessed using verbal response and visual analog scale at hours 6 and 12 and on days 1, 2, 7 and 14, respectively after operation. The verbal response scales had four options: no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain. The visual analogue scale consisted of a 10-cm line with the words “no pain” on the left hand side and “worst pain imaginable” on the right. Two types of pain were assessed, pain on defecation and pain during the preceding 24 h. The scales for pain on defecation were completed immediately after defecation and the scales for 24 h pain completed each evening. In order that pain could be assessed for seven postoperative days, patients were asked to complete the forms at hospital. Patients were discharged from hospital at the discretion of their consultants.

The use of narcotic drugs, antibiotics and laxatives, complication symptoms and hospital stay in all the patients were recorded after surgery. At the conclusion of the study, the codes were broken and the results were analyzed. The visual analogue scores were measured in cm, and the score for each 24 h was a single value. The score for pain on defecation was the mean value of scores during that day.

Statistical analysis

Before initiating the trial, sample size was calculated using SPSS software 15.0 version. A power calculation estimated that 40 patients would be needed in each group to demonstrate a reduction of 20% pain with a power of 80% and at a 5% significance level. Discrete variables were analyzed using χ2 test with Yates correction when appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed tests for pared observations. Pain scores at each time interval were compared between groups with Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test (nonparametric analysis of ranked data). A two-tailed Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated where indicated. Statistical significance was assumed when P < 0.05. Statistical evaluation was done as intend-to-treat analysis. When not otherwise specified, data were presented as median and range.

RESULTS

After standard hemorrhoid surgery, 86 patients were allocated to receive Diosmin (experimental group, n = 43) and placebo capsules (control group, n = 43). None of the patients in either study group complained of any severe symptoms during the 90-d follow-up after treatment. The two groups were well matched for age, sex, disease grades, and number of piles. There were no statistical differences between the two groups in these aspects (Table 1).

The Diosmin group defecated earlier (P = 0.00), had more frequent bowel actions in the first postoperative week (P = 0.00), and had a shorter hospital stay (P = 0.03) compared with the placebo group (Table 2). No patient withdrew from the study because of any complaints. Significantly more placebo patients were troubled by minor rectal bleeding at 2 wk, although these rates were similar at 8 wk. The follow-up after 8 wk found that two patients experienced minor bleeding in Diosmin group, and therefore, underwent surgery. There was a statistically significant (P < 0.05) improvement in pruritus and heaviness at both 2 and 8 wk (Table 3). In addition, there was no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of wound mucosal discharge.

Table 2.

Postoperative course of Diosmin and control groups

| Diosmin group1 (n = 43) | Control group2 (n = 43) | P value | |

| Median hospital stay (d) | 6.1 ( 1.3) | 7.3 (3.4) | 0.0306 |

| Median time to first bowel action (h) | 48 (4.2) | 56 (4.6) | 0 |

| Median No. of bowel actions in the first week | 9 (2.3) | 14 (3.1) | 0 |

Patients treated with Diosmin;

Patients treated with placebo drug.

Table 3.

Postoperative symptoms of Diosmin and control groups n (%)

| Diosmin group1(n = 43) | Control group2(n = 43) | P value | |

| Minor bleeding | |||

| At 2 wk | 3 (6.97) | 11 (25.58) | 0.0409 |

| At 8 wk | 2 (4.65) | 3 (4.64) | 0.6449 |

| Heaviness | |||

| At 2 wk | 4 (9.30) | 14 (32.56) | 0.0171 |

| At 8 wk | 2 (4.65) | 8 (18.60) | 0.0436 |

| Pruritus | |||

| At 2 wk | 9 (20.93) | 18 (41.86) | 0.0365 |

| At 8 wk | 3 (6.97) | 10 (23.25) | 0.0351 |

| Mucosal discharge | |||

| At 2 wk | 7 (16.28) | 11 (25.58) | 0.2890 |

| At 8 wk | 2 (4.64) | 4 (9.30) | 0.3972 |

Patients treated with Diosmin;

Patients treated with placebo drug.

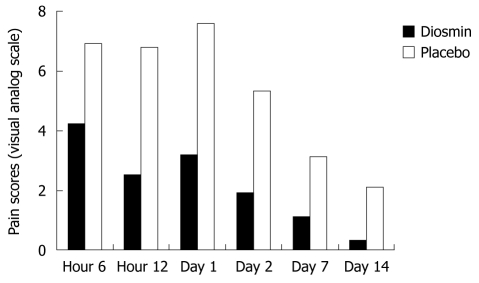

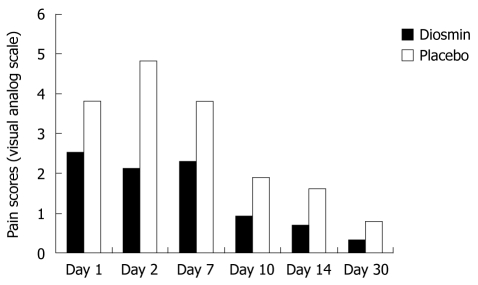

Patients in Diosmin group experienced significantly less pain at 6 and 12 h after surgery (P = 0.03, P < 0.01), and on days 1, 2, 7, 10, and 14 (P = 0.02, P < 0.01, P = 0.02, P = 0.03, P < 0.01) (Figure 2). There was also significant (P < 0.001) improvement on the proctoscopic appearance. Patients in the experimental group had significantly less defecation pain compared with the placebo group on days 1, 2, 7, 10, 14, and 30 (P = 0.03, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P = 0.02, P = 0.04, P = 0.04) (Figure 3). No significant Diosmin-related complications or allergic reactions were reported by any patient. A similar number of patients reported burning with both treatments at the 2nd week after surgery (3 in Diosmin and 2 in placebo).

Figure 2.

Postoperative pain scores in Diosmin and placebo groups. Pain scores ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (very severe pain).

Figure 3.

Pain on defecation in Diosmin and placebo groups. Pain scores ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (very severe pain).

DISCUSSION

Haemorrhoid is a common disease affecting people of all ages and both sexes. It is estimated that 50% of the people older than 50 years have hemorrhoid symptoms at least for a period of time. The causes of haemorrhoidal disease are multiple, but most are attributable to difficult passage of stool or constipation. Over the last few years, there has been increasing attention on surgical procedures to treat haemorrhoids. Several comparative studies have been performed to evaluate the available procedures to treat grades II, III, and IV hemorrhoids, and new surgical techniques, such as haemorrhoidectomy with Harmonic scalpel®[21-23] and Ligasure™[24], Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal plexus ligation[25,26] and the stapled haemorrhoidopexy[27-31]. The most recent medium- and long-term studies on ample case series provide data on the efficacy, the results and complications of these techniques[24-31]. None of them proved to reduce complications such as pain and bleeding[21]. The ideal method should combine the high safety and efficacy of the treatment, yielding low postoperative pain and bringing comfort to the patients. Such considerations are related to the severity of the disease and can be addressed by evidence-based medicine by randomized, controlled trial. According to a recent meta-analysis of the Cochrane library[32,33], conventional haemorrhoidectomy as first described by Milligan and Morgan, is still the most widely used, effective, and definite surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic grades III and IV haemorrhoids. However, it is associated with significant postoperative complications such as pain, bleeding and mucous discharge. Although there is a consensus on the treatment of grades III and IV haemorrhoids, there is still confusion regarding the ideal treatment for these complications after surgery.

In 1971, Daflon, consisting of 90% Diosmin and 10% Hesperidin (Daflon 500; Serdia Pharmaceuticals, India and Vinosmin; Elder Pharmaceuticals, India), was firstly introduced in France by Bensaude et al[34] for the treatment of haemorrhoids and other capillovenous diseases. Diosmin mainly works on the inflammatory pathology of haemorrhoids by increasing the contraction of veins and local lymphatic drainage and decreasing the synthesis of prostaglandins such as PGE2 and thromboxane B2[35-37]. The anti-inflammatory effects of Diosmin are reflected in the reduction of capillary hyperpermeability and fragility in controlled clinical studies. Damom et al[38] found the same effects of Diosmin in increasing the duration of vascular contraction and prostaglandin components which are responsible for the inflammatory process. Diosmin also increases the local lymphatic drainage. Side-effects of the drugs are limited according to Meyer[39] who was first used Diosmin to treat hemorrhoid symptoms. He reported mild gastrointestinal and autonomic disturbances in 10% cases. A fixed micronized combination of the citrus bioflavonoids Diosmin (90%) and hesperidin (10%) has been widely used in Europe to treat diseases of the blood vessels and lymphatic system since 2000. The combination also appears to be beneficial for chronic venous insufficiency and venous stasis ulcers. Extensive safety evaluations have found that Diosmin/hesperidin was free from toxicological risk. From 2005, Diosmin was used to treat vascular diseases[40-45]. The obtained evidence strongly supports its use in haemorrhoids in recent years although only several randomized controlled trials were available.

In this randomized trial, we concluded that Diosmin leads to the rapid cessation of haemorrhoidal bleeding, alleviation of the associated symptoms and gives objective relief from complications of post-haemorrhoidectomy. This result is similar to Mlakar’s study[46]. In their study, Flavonoids was found very effective in the first 30 d of treatment and led to the rapid relief of various associated symptoms of haemorrhoid surgery. Because, up to now, there have only a few randomized controlled studies to investigate the effectiveness and safety of Diosmin to treat symptoms after haemorrhoidectomy in the world, we could not perform meta-analysis for these studies. In our study, Diosmin was more effective to control postoperative pain than placebo capsules during the early phase of the surgery. This is a highlight in our study. The Diosmin group defecated earlier (P < 0.05), had more frequent bowel actions in the first postoperative week (P < 0.05), and had a shorter hospital stay (P < 0.05) compared with the placebo group. This is and a striking result compared with Mlakar’s study[46]. In spite of some minor bleeding, no patient withdrew from the study because of any kind of adverse events. This may be associated with proper drug usage after surgery, especially in the early phases. Significantly more placebo patients were troubled by minor rectal bleeding at 2 wk, although these rates were similar at 8 wk. However, during the follow-up after 8 wk, we found that two patients had minor bleeding in experimental group, therefore, they underwent surgery. Postoperative bleeding is a particularly important complication in hemorrhoids treatment due to its frequency varying between 0.6% and 10%[15,47]. Sometimes bleeding may be alarming, because it may cause anemia very rapidly in the patients. Several randomized controlled studies evaluated the use of oral micronized, purified flavonoid fraction in the treatment of haemorrhoidal bleeding. In these studies, bleeding was relieved rapidly, and no complication was reported. This is somewhat conflict with our bleeding cases. However, we used 500 mg Diosmin capsules compared with 450 mg micronized purified flavonoid fraction in Yo YH’s study[16]. The most important reason of our poor result related with bleeding is that we included grades III and IV piles, but Yo YH’s study included only grades I, II, and III piles. A similar study of 100 patients reported that acute bleeding had subsided by the third day of treatment in 80% of patients receiving micronized flavonoids, 2 d sooner than in patients receiving a placebo. But, the different points compared with our trial, which were also disadvantages of their studies, were associated with the difference of their study designs. They compared micronized flavonoids medication with hemorrhoid surgery itself. Although we think Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy is the most widely practiced “gold standard” surgical approach and the stages III and IV are the clear indication for this procedure, it is not necessary to alter the indication for hemorrhoid surgery to medication. Another point is the cost of medication. A limitation of the drug is the lack of patient compliance due to the long duration of treatment and the high cost of the drug. The safety of the drug has already been proved but more studies need to be done to see if the total dose of Diosmin can be increased so as to increase the response rate and decrease the duration of postoperative treatment. A decrease in the cost of the drug should also be considered.

Purified flavonoid fraction is a botanical extract from citrus. It exerts its effects on both diseased and intact vasculature, increasing vascular tone, lymphatic drainage, and capillary resistance; it is also assumed to have anti-inflammatory effects and promote wound healing. In another recent randomized controlled trial, postoperative use of micronized, purified flavonoid fraction, in combination with short-term routine antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy, reduced both the duration and extent of postoperative symptoms and wound bleeding after haemorrhoidectomy, compared with antibiotic and anti-inflammatory treatment alone[18].

Postoperative pain is the most important uncomfortableness which was also our predominant observatory parameter. Post haemorrhoid pain is difficult to assess, though verbal response scales and visual analogue scales are recognized methods. Maxwell concluded that the t test is “very robust” when comparing differences between visual analogue scale scores[48], and we therefore used this method of analysis. On two occasions, the verbal response scale in pain was a day less than the visual analogue scale. This may be because the discrete verbal response scale is less sensitive than the continuous visual analogue scale. Another highlight in our study was that patients in Diosmin group experienced significantly less pain at hours 6 and 12 (P < 0.05), and on days 1, 2, 7, 10, and 14 after surgery (P < 0.05). At the same time, patients in the experimental group had significantly less defecation pain compared with placebo groups on days 1, 2, 7, 10, 14 and 30 after surgery (P < 0.05). The exact cause of pain after haemorrhoidectomy has not yet to be defined. Various factors believed to be responsible for the pain including incarceration of smooth muscle fibers and mucosa in the transfixed vascular pedicle, epithelial denudation of the anal canal, and spasm of the internal sphincter[3]. Another reason for pain could be the development of linear wounds extending up to the anorectal ring, which appear similar to those of a chronic anal fissure[18]. Postoperative pain was also associated with bacterial fibrinolysis and defecation stress[49]. In our study, postoperative pain in the placebo group can be explained by the traction of the nonsensitive sliding haemorrhoidal tissue at the highly sensitive anal skin. The diminished postoperative pain in the Diosmin group might be related to its capillary resistance and diminished tissue edema and anti-inflammatory process. There was significant difference in different postsurgical days and weeks. Based on these results, we suggested that Diosmon has a clear action against anorectic postoperative pain. Therefore, it should be considered initially for patients presenting with haemorrhoidal symptoms after surgery. In addition, there was also a significant improvement on the proctoscopic appearance (P < 0.001).

Although there was a statistically significant improvement in heaviness and pruritus from baseline to the 8th week postoperatively, however, there were no statistical differences between the two groups in terms of wound mucosal discharge (P < 0.05). Our hypothesis was that our nonabsorbable suture used for internal mucosa ligation is responsible for this poor result.

In a 12-wk study of 50 pregnant women suffering from acute hemorrhoids, micronized Diosmin/hesperidin therapy was reported to be a “safe, acceptable and effective” treatment, and 66% obtained relief from symptoms within 4 d[50]. However, we suggest not using Diosmin for pregnant women, considering Diosmin is a new alternative for hemorrhoids.

This study has shown that Diosmin can reduce the complications from haemorrhoidectomy, especially in the early phase. We therefore suggest that this regimen should be a part of the routine postoperative management of patients for haemorrhoidectomy.

In conclusion, Diosmin (flavonidic fraction) has shown to be effective in alleviating symptoms after haemorrhoidal surgery and improving the proctoscopic appearance. Therefore, it should be considered initially for patients presenting with haemorrhoidal symptoms after surgery. However, further prospective randomized trials and longer follow-up are needed to confirm the findings of this study and observe the side effects of this drug.

COMMENTS

Background

Over the past few years, there has been increasing attention on surgical procedures to treat haemorrhoids. The Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy is still a major surgical approach for haemorrhoids. This study was designed to evaluate the influence of Diosmin on reducing postoperative pain, bleeding, heaviness, pruritus, and mucosal discharge after the Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy in a randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Research frontiers

Phlebotropic activity, protective effect on the capillaries and the anti-inflammatory effect of Diosmin have been reported in several studies in recent years. More recent clinical studies showed that flavonoid fraction such as Dalfon (phlebotropic agent) can reduce postoperative pain, bleeding and heaviness after haemorrhoidectomy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This clinical trial has confirmed that Diosmin (flavonoid fraction) can reduce postoperative pain, bleeding and heaviness after Milligan-Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy.

Applications

Diosmin (flavonidic fraction) has shown to be effective in alleviating symptoms after haemorrhoidal surgery and improving the proctoscopic appearance. Therefore, it should be considered initially for patients presenting with haemorrhoidal symptoms after surgery. However, further prospective randomized trials and longer follow-up are needed to confirm the findings of this study and observe the side effects of this drug.

Terminology

Diosmin is derived from some plants or used as a high-quality active ingredient in vein improvement supplements. Diosmin reduces inflammation and increases duration of vascular contraction that contributes to hemorrhoids.

Peer review

The authors engagingly described a pathomechanism of anal pain after haemorrhoidectomy and Diosmin’s action. The article is worth publishing.

Footnotes

Supported by The Biological Medical Engineering Foundation of First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University

Peer reviewers: Giuseppe Brisinda, MD, Catholic Medical School, University Hospital “Agostino Gemelli”, Largo Agostino Gemelli 8, Rome 00168, Italy; Mariusz Madalinski, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, IpswichHospital, Heath Road, IpswichIP4 5DP, United Kingdom

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Davies J, Duffy D, Boyt N, Aghahoseini A, Alexander D, Leveson S. Botulinum toxin (botox) reduces pain after hemorrhoidectomy: results of a double-blind, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1097–1102. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimitroulopoulos D, Tsamakidis K, Xinopoulos D, Karaitianos I, Fotopoulou A, Paraskevas E. Prospective, randomized, controlled, observer-blinded trial of combined infrared photocoagulation and micronized purified flavonoid fraction versus each alone for the treatment of hemorrhoidal disease. Clin Ther. 2005;27:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson TJ, Armstrong D. Topical metronidazole (10 percent) decreases posthemorrhoidectomy pain and improves healing. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:711–716. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0129-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abo-hashem AA, Sarhan A, Aly AM. Harmonic Scalpel compared with bipolar electro-cautery hemorrhoidectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2010;8:243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozer MT, Yigit T, Uzar AI, Mentes O, Harlak A, Kilic S, Cosar A, Arslan I, Tufan T. A comparison of different hemorrhoidectomy procedures. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:1264–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohn VY, Martin MJ, Mullenix PS, Cuadrado DG, Place RJ, Steele SR. A comparison of open versus closed techniques using the Harmonic Scalpel in outpatient hemorrhoid surgery. Mil Med. 2008;173:689–692. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.7.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok SY, Chung CC, Tsui KK, Li MK. A double-blind, randomized trial comparing Ligasure and Harmonic Scalpel hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:344–348. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0845-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batori M, Straniero A, Pipino R, Chatelou E, Sportelli G. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy in the treatment of hemorrhoid disease. Our eight-year experience. Minerva Chir. 2010;65:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Systematic review on the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (stapled hemorrhoidopexy) Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:878–892. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pattana-Arun J, Sooriprasoet N, Sahakijrungruang C, Tantiphlachiva K, Rojanasakul A. Closed vs ligasure hemorrhoidectomy: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung CC, Cheung HY, Chan ES, Kwok SY, Li MK. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs. Harmonic Scalpel hemorrhoidectomy: a randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1213–1219. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0918-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheetham MJ, Phillips RK. Evidence-based practice in haemorrhoidectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:126–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carapeti EA, Kamm MA, McDonald PJ, Chadwick SJ, Phillips RK. Randomized trial of open versus closed day-case haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:612–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chik B, Law WL, Choi HK. Urinary retention after haemorrhoidectomy: Impact of stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:233–237. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pescatori M. Closed vs. open hemorrhoidectomy: associated sphincterotomy and postoperative bleeding. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1174–1175. doi: 10.1007/BF02236571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho YH, Foo CL, Seow-Choen F, Goh HS. Prospective randomized controlled trial of a micronized flavonidic fraction to reduce bleeding after haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1034–1035. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diana G, Catanzaro M, Ferrara A, Ferrari P. [Activity of purified diosmin in the treatment of hemorrhoids] Clin Ter. 2000;151:341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Torre F, Nicolai AP. Clinical use of micronized purified flavonoid fraction for treatment of symptoms after hemorrhoidectomy: results of a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:704–710. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Idänpään-Heikkilä JE. WHO guidelines for good clinical practice (GCP) for trials on pharmaceutical products: responsibilities of the investigator. Ann Med. 1994;26:89–94. doi: 10.3109/07853899409147334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan S, Pawlak SE, Eggenberger JC, Lee CS, Szilagy EJ, Wu JS, Margolin M D DA. Surgical treatment of hemorrhoids: prospective, randomized trial comparing closed excisional hemorrhoidectomy and the Harmonic Scalpel technique of excisional hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:845–849. doi: 10.1007/BF02234706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramadan E, Vishne T, Dreznik Z. Harmonic scalpel hemorrhoidectomy: preliminary results of a new alternative method. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s101510200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan JJ, Seow-Choen F. Prospective, randomized trial comparing diathermy and Harmonic Scalpel hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:677–679. doi: 10.1007/BF02234565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palazzo FF, Francis DL, Clifton MA. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus open haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:154–157. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkerson PM, Strbac M, Reece-Smith H, Middleton SB. Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation: long-term outcome and patient satisfaction. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:394–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wałega P, Scheyer M, Kenig J, Herman RM, Arnold S, Nowak M, Cegielny T. Two-center experience in the treatment of hemorrhoidal disease using Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation: functional results after 1-year follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2379–2383. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burger JW, Eddes EH, Gerhards MF, Doornebosch PG, de Graaf EJ. [Two new treatments for haemorrhoids. Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation and stapled anopexy] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganio E, Altomare DF, Milito G, Gabrielli F, Canuti S. Long-term outcome of a multicentre randomized clinical trial of stapled haemorrhoidopexy versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1033–1037. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho YH, Seow-Choen F, Tsang C, Eu KW. Randomized trial assessing anal sphincter injuries after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1449–1455. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bove A, Bongarzoni G, Palone G, Chiarini S, Calisesi EM, Corbellini L. Effective treatment of haemorrhoids: early complication and late results after 150 consecutive stapled haemorrhoidectomies. Ann Ital Chir. 2009;80:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laughlan K, Jayne DG, Jackson D, Rupprecht F, Ribaric G. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy compared to Milligan-Morgan and Ferguson haemorrhoidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayaraman S, Colquhoun PH, Malthaner RA. Stapled versus conventional surgery for hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD005393. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005393.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan EK, Cornish J, Darzi AW, Papagrigoriadis S, Tekkis PP. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes of randomized controlled trials of LigaSure vs conventional hemorrhoidectomy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1209–1218; discussion 1218. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bensaude A, Vigule R, Naouri J. The Medical Treatment of Acute Haemorrhoidal Premenstrual episodes and haemorrhoidal congestion. La Vie Medicate 1971- 1972;52:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manthey JA. Biological properties of flavonoids pertaining to inflammation. Microcirculation. 2000;7:S29–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korthuis RJ, Gute DC. Adhesion molecule expression in postischemic microvascular dysfunction: activity of a micronized purified flavonoid fraction. J Vasc Res. 1999;36 Suppl 1:15–23. doi: 10.1159/000054070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kavutcu M, Melzig MF. In vitro effects of selected flavonoids on the 5'-nucleotidase activity. Pharmazie. 1999;54:457–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Damom M, Flandre O, Michel F, Perdix L, Labrid C, Crastes de. Paulet. Effect of chronic treatment with a flavanoid fraction on inflammatory granuloma. Drug Res. 1987;37:1149–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer OC. Safety and security of Daflon 500 mg in venous insufficiency and in hemorrhoidal disease. Angiology. 1994;45:579–584. doi: 10.1177/000331979404500614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benavente-García O, Castillo J. Update on uses and properties of citrus flavonoids: new findings in anticancer, cardiovascular, and anti-inflammatory activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:6185–6205. doi: 10.1021/jf8006568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inan A, Sen M, Koca C, Akpinar A, Dener C. The effect of purified micronized flavonoid fraction on the healing of anastomoses in the colon in rats. Surg Today. 2006;36:818–822. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernández SP, Wasowski C, Loscalzo LM, Granger RE, Johnston GA, Paladini AC, Marder M. Central nervous system depressant action of flavonoid glycosides. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;539:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lahouel M, Boulkour S, Segueni N, Fillastre JP. [The flavonoids effect against vinblastine, cyclophosphamide and paracetamol toxicity by inhibition of lipid-peroxydation and increasing liver glutathione concentration] Pathol Biol (Paris) 2004;52:314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanaze FI, Gabrieli C, Kokkalou E, Georgarakis M, Niopas I. Simultaneous reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of diosmin, hesperidin and naringin in different citrus fruit juices and pharmaceutical formulations. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2003;33:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(03)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Korthui RJ, Gute DC. Anti-inflammatory actions of a micronized, purified flavonoid fraction in ischemia/reperfusion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;505:181–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mlakar B, Kosorok P. Flavonoids to reduce bleeding and pain after stapled hemorrhoidopexy: a randomized controlled trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:558–560. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chik B, Law WL, Choi HK. Urinary retention after haemorrhoidectomy: Impact of stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:233–237. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maxwell C. Sensitivity and accuracy of the visual analogue scale: a psycho-physical classroom experiment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;6:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb01676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balfour L, Stojkovic SG, Botterill ID, Burke DA, Finan PJ, Sagar PM. A randomized, double-blind trial of the effect of metronidazole on pain after closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1186–1190; discussion 1190-1191. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buckshee K, Takkar D, Aggarwal N. Micronized flavonoid therapy in internal hemorrhoids of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;57:145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(97)02889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]