Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic obliteration with Histoacryl® for treatment of gastric variceal bleeding and prophylaxis.

METHODS: Between January 1994 and March 2010 at SoonChunHyang University Hospital, a total of 127 patients with gastric varices received Histoacryl® injections endoscopically. One hundred patients underwent endoscopic Histoacryl® injections because of variceal bleeding, the other 27 patients received such injections as a prophylactic procedure.

RESULTS: According to Sarin classification, 56 patients were GOV1, 61 patients were GOV2 and 10 patients were IGV. Most of the varices were large (F2 or F3, 111 patients). The average volume of Histoacryl® per each session was 1.7 ± 1.3 cc and mean number of sessions was 1.3 ± 0.6. (1 session-98 patients, 2 sessions-25 patients, ≥ 3 sessions-4 patients). Twenty-seven patients with high risk of bleeding (large or fundal or RCS+ or Child C) received Histoacryl® injection as a primary prophylactic procedure. In these patients, hepatitis B virus was the major etiology of cirrhosis, 25 patients showed GOV1 or 2 (92.6%) and F2 or F3 accounted for 88.9% (n = 24). The rate of initial hemostasis was 98.4% and recurrent bleeding within one year occurred in 18.1% of patients. Successful hemostasis during episodes of rebleeding was achieved in 73.9% of cases. Median survival was 50 mo (95% CI 30.5-69.5). Major complications occurred in 4 patients (3.1%). The rebleeding rate in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or GOV2 was higher than in those with other conditions. None of the 27 subjects who were treated prophylactically experienced treatment-related complications. Cumulative survival rates of the 127 patients at 6 mo, 1, 3, and 5 years were 92.1%, 84.2%, 64.2%, and 45.3%, respectively. The 6 mo cumulative survival rate of the 27 patients treated prophylactically was 75%.

CONCLUSION: Histoacryl® injection therapy is an effective treatment for gastric varices and also an effective prophylactic treatment of gastric varices which carry high risk of bleeding.

Keywords: Gastric varix, Prophylaxis, Histoacryl® (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate), Histoacryl® injection, Treatment of gastric varix

INTRODUCTION

Gastric varices occur in 18%-70% of patients with portal hypertension[1,2] and are classified as gastro-esophageal varices (GOV) 1 (esophageal varix extending down to the cardia or lesser curve) or GOV2 (esophageal and fundal varices). Isolated gastric varices (IGV) may be located either in the fundus (IGV1) or elsewhere in the stomach (IGV2)[1]. Although the incidence of bleeding from gastric varices is relatively low (10%-36%), when it occurs it tends to be more severe, to require more transfusion, and to have a higher mortality rate than esophageal variceal bleeding[1,3-5] while acute bleeding is controlled. Gastric varices have a high rate of rebleeding (38%-89%)[6-8]. Precisely what triggers a bleed from a gastric varix is not known. However a number of risk factors for gastric variceal bleeding have been identified: location in the fundus, advanced Child’s stage, presence of red spots, and increasing size of the varices are the important factors in determining the risk of a first bleed from gastric varices[9,10].

A number of treatment modalities for acute gastric variceal bleeding and prevention of bleeding are available. These include endoscopic treatment (sclerotherapy, band ligation, etc), TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt), and B-RTO (balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration). Of these, the first-line treatment for gastric variceal bleeding is endoscopic obliteration with Histoacryl® (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate)[11,12].

Though it has been used worldwide for the treatment for gastric varices, data regarding the long-term efficacy and safety of this procedure are still lacking. Indeed, although rare, fatal complications do occur[13,14].

We evaluated the long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic obliteration with Histoacryl® for treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in terms of the prevalence of complications, ability to predict rebleeding and survival rates. Furthermore, the efficacy, prevalence of complications and survival rates of prophylactic endoscopic injection sclerotherapy with Histoacryl for high risk gastric varices found incidentally also assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was a retrospective analysis of patients with cirrhosis who underwent endoscopic Histoacryl® injection. From January 1994 to March 2010, patients (127) who presented to our hospital with acute gastric varices as evidenced by hematemesis or melena, or who had gastric varices without bleeding evidence, were considered for enrollment. This included 100 patients with active gastric variceal bleeding and 27 with high-risk varices (large, located in the fundus, red color sign (RCS), Child C)[10] who underwent primary prophylaxis.

Of the 127 patients, 97 (76.4%) were male and 30 (23.6%) female, and the mean age was 55.69 years. The most common etiology of gastric varices was hepatitis B-related cirrhosis in 50 patients (39.3%), followed by alcoholic liver cirrhosis in 48 (37.8%), unknown in 19 (15%) and hepatitis C virus in 10 (7.9%). Twenty-one patients (16.5%) had been diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. The lesions of 42 patients (33.1%) were classified as Child-Pugh class A, 59 (46.4%) as Child-Pugh B, and 26 (20.5%) as Child-Pugh C. Endoscopic Histoacryl® injection was conducted within 24 h of gastric variceal bleeding in 48 patients (37.8%). Of the 127 patients, GOV1 was present in 56 (44.1%), GOV2 in 61 (48%), IGV1 in 8 (6.3%), and IGV2 in 2 (1.6%). Most varices (n = 111) were large (F2 or F3) (Table 1)[9].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics-127 patients treated with Histoacryl® -injection therapy

| Clinical characteristics of patients | Number | % |

| No. of patients (male/female) | 127(97/30) | 76.4/23.6 |

| Mean age (yr) | 55.69 | |

| Etiology of gastric varices | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 127 | 100 |

| Hepatitis B | 50 | 39.3 |

| Hepatitis C | 10 | 7.9 |

| Alcoholic | 48 | 37.8 |

| Unknown | 19 | 15 |

| Association of hepatocellular carcinoma | 21 | 16.5 |

| Child-pugh classification (A/B/C) | 42/59/26 | 33.1/46.4/20.5 |

| Bleeding status | ||

| < 24 h | 48 | 37.8 |

| > 24 h | 52 | 41 |

| Prevention | 27 | 21.2 |

| Sarin classification of gastro-esophageal varices | ||

| GOV1 | 56 | 44.1 |

| GOV2 | 61 | 48 |

| IGV1 | 8 | 6.3 |

| IGV2 | 2 | 1.6 |

| Form of gastric varices | ||

| F1 | 15 | 12 |

| F2 | 56 | 44.4 |

| F3 | 55 | 43.6 |

GOV: Gastro-esophageal varices; IGV: Isolated gastric varices.

Twenty-seven patients with high risk gastric varices underwent endoscopic Histoacryl® injection as a primary prophylaxis. Of these, 21 (71.4%) were male and six (28.6%) female, and the mean age was 55.29 years. The most common etiology of gastric varices was hepatitis B-related cirrhosis (14 patients, 51.9%), followed by alcoholic liver cirrhosis in 6 (22.2%). Five of the 27 (18.5%) patients were diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. Twelve (44.4%) were classified as Child-Pugh A and 11 (40.7%) as Child-Pugh B to Child-Pugh C. Of the 27, GOV1 was seen in 15 patients (55.6%) and GOV2 in 10 (37%). Most varices (n = 24) were categorized as size F2 or F3 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics-27 patients who underwent primary prophylaxis

| Clinical characteristics | Number | % |

| No. of patients (male/female) | 27(21/6) | 71.4/28.6 |

| Mean age (yr) | 55.29 | |

| Etiology of gastric varices | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 27 | 100 |

| Hepatitis B | 14 | 51.9 |

| Hepatitis C | 3 | 11.1 |

| Alcoholic | 6 | 22.2 |

| Unknown | 4 | 14.8 |

| Association of hepatocellular carcinoma | 5 | 18.5 |

| Child-Pugh classification (A/B/C) | 12/11/4 | 44.4/40.7/14.9 |

| Sarin classification of gastro-esophageal varices | ||

| GOV1 | 15 | 55.6 |

| GOV2 | 10 | 37 |

| IGV1 | 2 | 7.4 |

| IGV2 | 0 | 0 |

| Form of gastric varices | ||

| F1 | 3 | 11.1 |

| F2 | 9 | 33.3 |

| F3 | 15 | 55.6 |

GOV: Gastro-esophageal varices; IGV: Isolated gastric varices.

Treatment methods

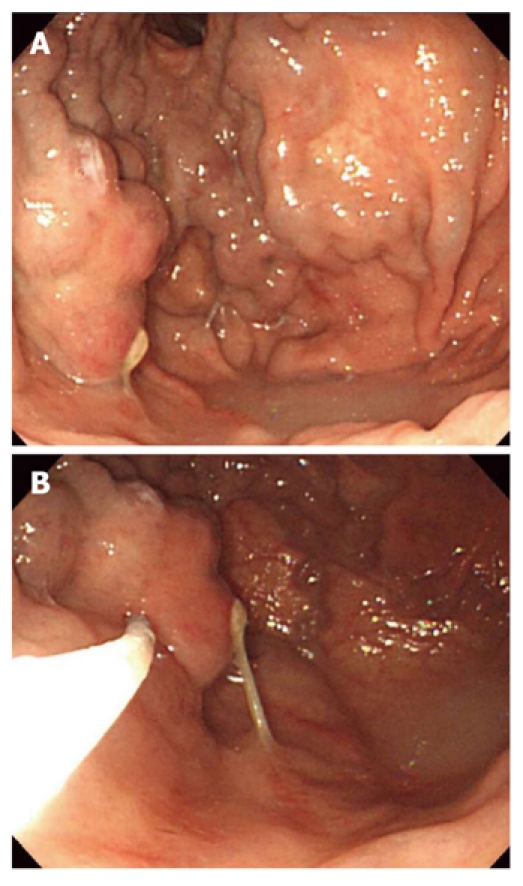

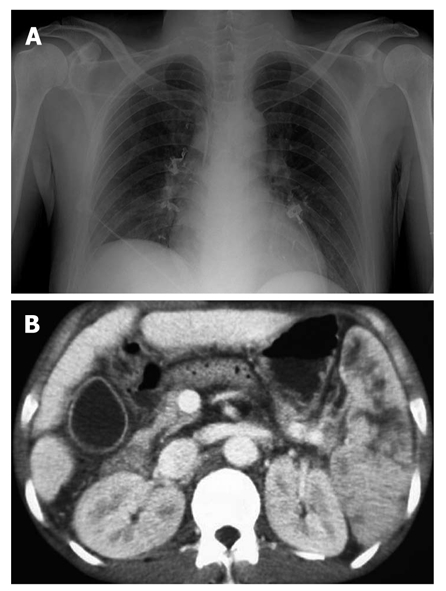

Histoacryl® injection was performed using a GIFQ 230 or GIFQ 240 endoscope (Olympus C, Tokyo, Japan) and 23-gauge disposable injection needle catheter (1650 mm in length). Each shot contained 1.0-2.0 cc Histoacryl® and an equal volume of Lipiodol (Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France). The endoscopic suction channel was flushed with lubricant (olive oil) before insertion of the catheter. The preload sclerotherapy catheter was advanced through the endoscope into the stomach, and the needle was inserted directly in the gastric varix (Figure 1A and B). Immediately following injection of cyanoacrylate mixture into the gastric varix, the location of lipiodol in the gastric varix was assessed using fluoroscopic visualization (Figure 2). Lipiodol was given through the catheter to deliver the glue mixture into the varix, and the needle was then withdrawn while glue was still flowing to decrease the risk of needle embedment. The catheter was then flushed with sterile water. Typically 2 cc of a 1:1 mixture of lipiodol and Histoacryl® was administered per injection. Injections were repeated until gastric varices appeared to occlude, as judged by probing with a blunt probe.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic Histoacryl® injection for treatment of gastric varices. A: Endoscopic image showing a large gastric varix; B: Injection of Histoacryl® into the gastric varix using the catheter.

Figure 2.

X-ray showing lipiodol in the gastric varix during the procedure.

Outcome measures

Successful hemostasis was defined as vital sign stability, no drop in hemoglobin and no rebleeding within 24 h of after sclerotherapy. Rebleeding was defined as hematemesis and/or melena, hypotension (a drop in systolic blood pressure of > 20 mm Hg from baseline), 2 mg/dL fall in hemoglobin and/or transfusion requirement of ≥ 2 units of packed red blood cells after 24 h.

Statistical analysis

Statistical interpretation of data was performed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14. Results were expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as numbers (percentage) for categorical data. Analysis was performed using the independent t-test, χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier method and then log rank test were used to examine predictive factors of rebleeding rate within 1 year and survival rates.

RESULTS

Hemostatic outcomes

A total of 162 endoscopies were performed and the mean number of sessions was 1.3 ± 0.6. Obliteration of gastric varices was achieved with one session in 98 patients and two sessions in 25. Four patients required three or more sessions. The mean volume of Histoacryl® administered was 1.7 ± 1.3 cc. Initial hemostasis was achieved in 125 patients (98.4%). Total number of rebleeding episodes in 127 patients was 29 (22.8%). The mean follow-up period of rebleeding was 322.71 ± 551.14 d. Episodes of rebleeding from 1 d to 1 year post-therapy occurred in 23 (18.1%) subjects with recurrent bleeding. One patient of these was considered to have treatment failure, whereas the others (22, 73.9%) experienced successful hemostasis after rebleeding (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of 127 Histoacryl®-injection patients

| Result of Histoacryl® injection | Number | % |

| No. of sessions | ||

| 1 | 98 | 77.1 |

| 2 | 25 | 19.7 |

| 3-5 (3/5) | 4 (3/1) | 3.2 |

| Mean number of sessions | 1.3 ± 0.6 | |

| Mean injection volume (cc) | 1.7 ± 1.3 | |

| Initial hemostasis | 125 | 98.4 |

| Number of rebleeding | 29 | 22.8 |

| Duration of rebleeding | ||

| < 5 d | 4 | 3.1 |

| < 6 wk | 10 | 7.9 |

| < 1 yr | 9 | 7.1 |

| Successful hemostasis of rebleeding | 22 | 73.9 |

Only one Histoacryl® treatment was needed in 21 of 27 subjects (77.8%) who underwent primary prophylaxis. The other 6 patients received several sessions of Histoacryl® injection therapy because of incomplete obliteration of varices. The mean volume of Histoacryl® administered to these individuals was 2.1 cc. Three patients died due to hepatic failure and one due to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). No prophylactic treatment-related complications were noted (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of 27 patients with primary prophylaxis

| Result of Histoacryl® injection | Number | % |

| No. of sessions | ||

| 1 | 21 | 77.8 |

| 2 | 4 | 14.8 |

| 3-5 (3/5) | 2 (1/1) | 3.7/3.7 |

| Mean number of sessions | 1.37 | |

| Mean injection volume (cc) | 2.1 | |

| Number of patients | 27 | |

| Death | 4 | 14.8 |

| Hepatic failure | 3 | 11.1 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 | 3.7 |

| Prophylactic treatment- related complication | 0 | 0 |

Complications

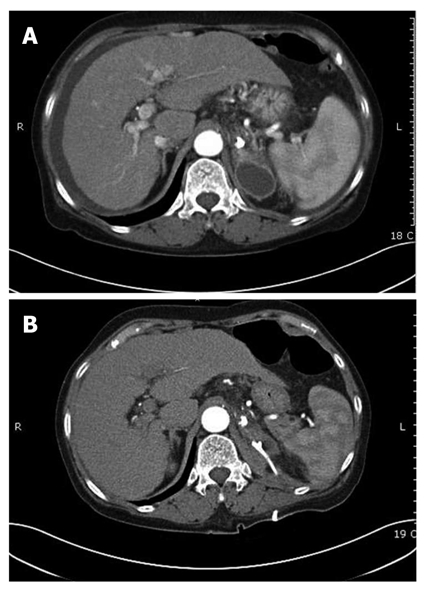

Complications were observed in 73/127 patients. The most common was fever (n = 44), followed by mild abdominal pain (n = 22) which subsided within 24 h. Two patients developed post-treatment infections; Klebsiella pneumonia and Escherichia coli were indentified through blood cultures. One developed pulmonary embolism (Figure 3A) and one patient suffered splenic infarction (Figure 3B); two patients developed adrenal abscesses (Figure 4A). Adrenal abscesses were drained through the catheter percutaneously, and both individuals recovered fully (Figure 4B). A conservative treatment strategy for both pulmonary embolism and splenic infarction was conducted (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Embolic complications of Histoacryl® injection. A: Chest radiography showing pulmonary embolism after Histoacryl® injection; B: Computed tomography showing the presence of lipiodol in the splenic vein after Histoacryl® injection.

Figure 4.

Adrenal abscess after Histoacryl® injection. A: Computed tomography scan showing adrenal abscess after Histoacryl® injection; B: Adrenal abscess was resolved after PCD insertion.

Table 5.

Complications of Histoacryl® injection

| Complications | Number |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 |

| Adrenal abscess | 2 |

| Splenic infarction | 1 |

| Bacteremia | 2 |

| Fever | 44 |

| Abdominal pain | 22 |

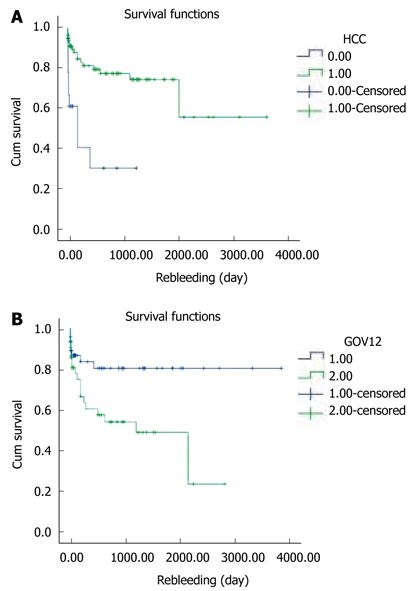

Predictive factors of rebleeding

Rebleeding occurred in 9 of 21 patients with HCC (P = 0.000). Also it occurred in 15 patients with GOV2 and 8 patients with GOV 1 (P = 0.009). The presence of HCC or GOV2 by Sarin classification was significantly associated with rebleeding within 1 year of the initial Histoacryl® injection (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5.

The 1-year rebleeding rate using the Kaplan-Meier method and then log rank test. A: Comparing the groups with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or without HCC; B: Comparing GOV1 and GOV2. GOV: Gastro-esophageal varices.

One year rebleeding rates were not associated with sex (P = 0.597), the cause of cirrhosis (P = 0.707), forms of varices (P = 0.269), time from bleeding to hemostasis (P = 0.815) or CTP grade (P = 0.230) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Predictive factors of rebleeding within 1 year

| Clinical characteristics | Rebleeding | Non rebleeding | P |

| Sex | 0.597 | ||

| Male | 17 | 80 | |

| Female | 6 | 24 | |

| Etiology | 0.707 | ||

| Hepatitis B | 11 | 39 | |

| Hepatitis C | 2 | 8 | |

| Alcoholic | 6 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 4 | |

| Association of hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.000 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 12 | |

| No | 14 | 92 | |

| Sarin classification of gastro-esophageal varices | 0.009 | ||

| GOV1 | 8 | 48 | |

| GOV2 | 15 | 46 | |

| Form of gastric varices | 0.269 | ||

| F1 | 1 | 14 | |

| F2 | 11 | 45 | |

| F3 | 11 | 44 | |

| Duration | 0.815 | ||

| < 24 h | 17 | 80 | |

| > 24 h | 6 | 24 | |

| CTP grade | 0.230 | ||

| A | 6 | 36 | |

| B | 9 | 52 | |

| C | 8 | 16 |

GOV: Gastro-esophageal varices.

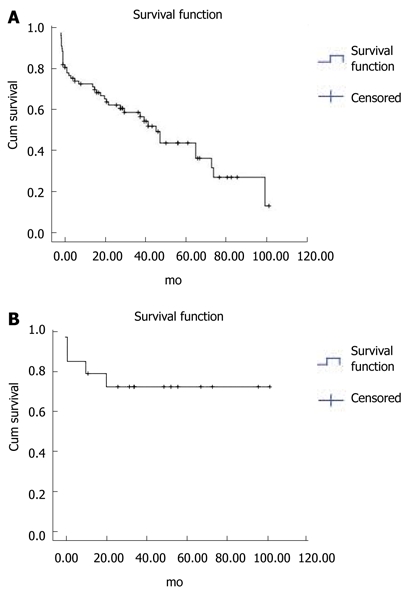

Survival

The median survival duration was 50 mo (95% CI 30.5-69.5). The cumulative survival rates of the 127 patients at 6 mo and at 1, 3, and 5 years were 92.1%, 84.2%, 64.2%, and 45.3%, respectively (Figure 6A). Four of the 27 patients who underwent primary prophylaxis died of hepatic failure or HCC (Table 4). The 6-mo cumulative survival rate of these patients was 75% (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Survival of Histoacryl® injected patients. A: Survival of 127 Histoacryl®-injected patients using the Kaplan-Meier method. The cumulative survival rates of the 127 patients at 6 mo, and 1, 3 and 5 years were 92.1%, 84.2%, 64.2%, and 45.3%, respectively; B: Survival of the 27 patients who underwent primary prophylaxis, using the Kaplan-Meier method. The 6 mo cumulative survival rate of these patients was 75%.

DISCUSSION

Gastric varices and their association with portal hypertension were first described in 1931[15]. The overall incidence of gastric varices in patients with portal hypertension is 18%-70%[1,2]. The incidence of bleeding from gastric varices is relatively lower, ranging from 10%-36%, compared with bleeding from esophageal varices[1]. Mortality associated with a first variceal bleed appears to have improved in recent years but remains as high as 20% within 6 wk of the index bleed[3,4].

Endoscopic injection of Histoacryl® is the currently recommended in recent consensus and guidelines as the initial treatment for acute gastric variceal bleeding[11,12]. Endoscopic injection of tissue glue for gastric variceal bleeding was first reported in 1986 by Soehendra et al[16]. However, the rebleeding rate remains high, at 22%-34% and episodic complications such as systemic embolism have been the main issues[13]. Cerebral stroke, portal vein embolization, splenic infarction, coronary embolism, and nonfatal pulmonary emboli in 4.6% of cases were reported as complications of tissue adhesive use[14,17-19]. But the complication rate was relatively low and most of the complications were not severe. The common adverse effects of Histoacryl® injection therapy include fever and abdominal discomfort. In this study, unusual adverse effects, such as pulmonary embolism, splenic infarction, and adrenal abscess were noted. We already reported two cases of adrenal abscess after NBC injection (Gut and Liver, article in press). The routes for gastric variceal drainage are gastro-renal shunt or gastro-caval shunt. In our cases, the adrenal abscesses developed 4-6 mo after the Histoacryl® injection. The reason why adrenal abscesses after Histoacryl® injection were so delayed is that insufficient drainage and stasis of adrenal vein blood by the Histoacryl® material made a significant contribution to abscess formation. In theory, using undiluted Histoacryl® may prevent distal embolization because the polymer solidifies rapidly upon contact with blood[20]. D’Imperio et al[21]studied undiluted Histoacryl® in 80 patients with bleeding gastric, esophageal, and duodenal varices. Distal embolization to distant abdominal sites occurred in two patients. Therefore, using undiluted Histoacryl® does not preclude the risk of embolisation. In our cases, all subjects recovered fully; no symptoms such as cough and chest pain caused by migration of Histoacryl® from the variceal location to the pulmonary vein were noted. PCD was inserted into the adrenal abscess and follow-up CT indicated completed resolution.

Accurate classification of gastric varices is essential in determining optimal management. The most widely used classification is that proposed originally by Sarin et al[1]. Unlike esophageal varices, a high porto-systemic pressure (> 12 mmHg) does not cause gastric variceal bleeding, likely due to the high frequency of spontaneous gastro-renal shunts[22]. In one study, fundal varices had a significantly higher bleeding incidence (78% and 55% for IGV1 and GOV2, respectively) than either GOV1 or IGV2 (10%)[23]. In the present study, of 127 patients, GOV1 was seen in 56 (44.1%), GOV2 in 61 (48%), IGV1 in 8 (6.3%), and IGV2 in 2 (1.6%). No significant difference in 1-year rebleeding rate rates between GOV 1 and GOV2 were detected (P = 0.173).

Billi et al[24] conducted a 24 mo follow-up of 50 patients who underwent Histoacryl® injections for gastric varices and reported that acute hemostasis was achieved in 92% of patients. Also Fuster et al[25] reported good results from Histoacryl® use in pediatric patients. In this study, the success rate of acute hemostasis was 98.4%, comparable to or better than that reported elsewhere[26,27].

The reported rebleeding rate after Histoacryl® injection for acute gastric variceal bleeding ranged from 22%-59%[26,28]. This was reduced by improvement of treatment technique, use of prophylactic antibiotics and effective vasoactive agents, and so on. Also the higher the MELD score was the more rebleeding occurred[29]. In our study the rebleeding rate was 22.8% (n = 29). This is consistent with other reports[26,28]. Episodes of rebleeding from 1 d to 1 year occurred in 23 patients (18.1%). Twenty-two patients experienced successful hemostasis after rebleeding (73.9%).

In our study, rebleeding within 1 year was associated with the presence of HCC (P = 0.000) and Sarin classification (GOV2) (P = 0.009). However, no statistically significant difference in rebleeding rates among Child-Pugh scores A, B, and C (P = 0.230) or form of gastric varices (P = 0.269), sex (P = 0.597) and etiology (P = 0.707) was found. We assume that complete obliteration in GOV2 is not easy because GOV2 is wider than GOV1, and that was the reason for more frequent rebleeding in GOV2 than GOV1.

Use of β-blockers for the primary prevention of gastric variceal bleeding is not supported by significant data[5]. Because the mortality rate of gastric variceal bleeding is high, it has been suggested that patients at high risk for bleeding should undergo primary prophylaxis of the gastric varix[10,30]. Hashizume et al[9] reported a number of risk factors for gastric variceal bleeding: red colored spots, larger nodular varix, and location in the fundus. According to Kim et al[10] advanced Child-Pugh class, varices > 5 mm in size, and the presence of a red spot were associated with an increased risk for a first bleed. On the basis of these facts, 27 patients with high-risk gastric varices (large, fundus, RCS, Child C) underwent primary prophylaxis with endoscopic Histoacryl® injection. Four of these patients died of hepatic failure or HCC. The others had survived to the time of writing this report. Thus the 6 mo cumulative survival rate of these patients was 75%. No treatment-related complications were noted.

In conclusion, Histoacryl® injection therapy is effective for the treatment of gastric varices with high initial hemostasis and rare complications. On the basis of our analysis, rebleeding rates were linked to the presence of HCC or GOV2. Furthermore, Histoacryl® injection therapy is effective for prophylaxis of gastric varices which carry high risk of bleeding.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric variceal bleeding tends to be more severe than esophageal variceal bleeding. Furthermore, acute bleeding was controlled, gastric varices have a high rate of rebleeding. Precisely what triggers a bleed from a gastric varix is not known. Also the effect of primary prophylaxis of gastric varices is not studied well.

Research frontiers

In this study, the authors demonstrate the long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic obliteration with Histoacryl® for treatment of gastric variceal bleeding and prophylaxis.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The rate of initial hemostasis was 98.4% and recurrent bleeding within one year occurred in 18.1% of patients. The rebleeding rate in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or GOV2 was higher than in those with other conditions. Median survival was 50 months (95% CI 30.5–69.5). Cumulative survival rates of the 127 patients at 6 months, 1, 3, and 5 years were 92.1%, 84.2%, 64.2%, and 45.3%, respectively. The 6-month cumulative survival rate of the 27 patients treated prophylactically was 75%.

Applications

Histoacryl® injection therapy is effective for the treatment of gastric varices with high initial hemostasis and rare complications. On the basis of our analysis, rebleeding rates were linked to the presence of HCC or GOV2. Furthermore, Histoacryl® injection therapy is effective for prophylaxis of gastric varices which carry high risk of bleeding.

Terminology

Histoacryl® (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) is a watery solution, which polymerizes and hardens within 20 seconds in a physiological milieu and instantaneously upon contact with blood. This makes it ideal for obliterating vessels and controlling bleeding. It is necessary to dilute it with the oily contrast agent Lipiodol® is not only compatible with the tissue glue for dilution but also allows fluoroscopic monitoring of delivery of the substance.

Peer review

The authors reported their results of a retrospective study on patients who underwent endoscopic NBC injection for gastric varices. Important data including the success rate of initial haemostasis, rebleeding rate, long-term complications and prognostic predictors were reported. Though being limited by the retrospective nature of the study, the strength of the study was the relatively large number of patients with active bleeding.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Yuk Him Tam, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1244–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe K, Kimura K, Matsutani S, Ohto M, Okuda K. Portal hemodynamics in patients with gastric varices. A study in 230 patients with esophageal and/or gastric varices using portal vein catheterization. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:434–440. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JL, Graham DY. Variceal hemorrhage: a critical evaluation of survival analysis. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:968–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amico G, de Franchis R. End-of the-century reappraisal of the 6-week outcome of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis. A prospective study (abstr) Gastroenterology. 1999;117:A1199. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. A pathophysiologic, gastroenterologic, and radiologic approach to the management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1175–1189. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trudeau W, Prindiville T. Endoscopic injection sclerosis in bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:264–268. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(86)71843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bretagne JF, Dudicourt JC, Morisot D, Thevenet F, Raoul JL, Gastard J. Is endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy effective for the treatment of gastric varices (abstr) Dig DIs Sci. 1986;31:A505S. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarin SK. Long-term follow-up of gastric variceal sclerotherapy: an eleven-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashizume M, Kitano S, Yamaga H, Koyanagi N, Sugimachi K. Endoscopic classification of gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:276–280. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim T, Shijo H, Kokawa H, Tokumitsu H, Kubara K, Ota K, Akiyoshi N, Iida T, Yokoyama M, Okumura M. Risk factors for hemorrhage from gastric fundal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:307–312. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v25.pm0009021939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laine L, Planas R, Nevens F, Banares R, Patch D, Bosch J. Treatment of the acute bleeding episode. In: Franchis R, editor. Consensus Workshop on Definitions, Methodology and Therapeutic Strategies. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2006. pp. 217–242. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naga M, Foda A. An unusual complication of histoacryl injection. Endoscopy. 1997;29:140. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu LK, Hsu CW, Tseng JH, Liu NJ, Sheen IS. Splenic infarction complicated by splenic artery occlusion after N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection for gastric varices: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:343–345. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02583-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soehendra N, Grimm H, Nam VC, Berger B. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a supplement to endoscopic sclerotherapy. Endoscopy. 1987;19:221–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soehendra N, Nam VC, Grimm H, Kempeneers I. Endoscopic obliteration of large esophagogastric varices with bucrylate. Endoscopy. 1986;18:25–26. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roesch W, Rexroth G. Pulmonary, cerebral and coronary emboli during bucrylate injection of bleeding fundic varices. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S89–S90. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang SS, Kim HH, Park SH, Kim SE, Jung JI, Ahn BY, Kim SH, Chung SK, Park YH, Choi KH. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate pulmonary embolism after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for gastric variceal bleeding. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:16–22. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palejwala AA, Smart HL, Hughes M. Multiple pulmonary glue emboli following gastric variceal obliteration. Endoscopy. 2000;32:S1–S2. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdullah A, Sachithanandan S, Tan OK, Chan YM, Khoo D, Mohamed Zawawi F, Omar H, Tan SS, Oemar H. Cerebral embolism following N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection for esophageal postbanding ulcer bleed: a case report. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:504–508. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Imperio N, Piemontese A, Baroncini D, Billi P, Borioni D, Dal Monte PP, Borrello P. Evaluation of undiluted N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in the endoscopic treatment of upper gastrointestinal tract varices. Endoscopy. 1996;28:239–243. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanley AJ, Jalan R, Ireland HM, Redhead DN, Bouchier IA, Hayes PC. A comparison between gastric and oesophageal variceal haemorrhage treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:171–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.106277000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343–1349. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billi P, Milandri GL, Borioni D, Fabbri C, Baroncini D, Cennamo V, Piemontese A, D’Imperio N. Endoscopic treatment of gastric varices with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a long term follow up. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:AB26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuster S, Costaguta A, Tabacco O, Sclerotherapy of bleeding gastric varices with cyanoacrylate in children (abstr) Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A1244. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan PC, Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology. 2006;43:690–697. doi: 10.1002/hep.21145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paik CN, Kim SW, Lee IS, Park JM, Cho YK, Choi MG, Chung IS. The therapeutic effect of cyanoacrylate on gastric variceal bleeding and factors related to clinical outcomes. J Clin Gastroeneterol. 2008;42:916–922. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31811edcd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo GH, Liang HL, Chen WC, Chen MH, Lai KH, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Chan HH, Pan HB. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy. 2007;39:679–685. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bambha K, Kim WR, Pedersen R, Bida JP, Kremers WK, Kamath PS. Predictors of early re-bleeding and mortality after acute variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2008;57:814–820. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto A, Matsumoto H, Hamamoto N, Kayazawa M. Management of gastric fundal varices associated with a gastrorenal shunt. Gut. 2001;48:440–441. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.440a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]