Abstract

Dunn, J. F., N. Khan, H. G. Hou, J. Merlis, M. A. Abajian, E. Demidenko, O.Y. Grinberg, and H. M. Swartz. Cerebral oxygenation in awake rats during acclimation and deacclimation to hypoxia: an in vivo EPR study. High Alt. Med. Biol. 12:71–77, 2011.— Exposure to high altitude or hypobaric hypoxia results in a series of metabolic, physiologic, and genetic changes that serve to acclimate the brain to hypoxia. Tissue Po2 (Pto2) is a sensitive index of the balance between oxygen delivery and utilization and can be considered to represent the summation of such factors as cerebral blood flow, capillary density, hematocrit, arterial Po2, and metabolic rate. As such, it can be used as a marker of the extent of acclimation. We developed a method using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) to measure Pto2 in unanesthetized subjects with a chronically implanted sensor. EPR was used to measure rat cortical tissue Pto2 in awake rats during acute hypoxia and over a time course of acclimation and deacclimation to hypobaric hypoxia. This was done to simulate the effects on brain Pto2 of traveling to altitude for a limited period. Acute reduction of inspired O2 to 10% caused a decline from 26.7 ± 2.2 to 13.0 ± 1.5 mmHg (mean ± SD). Addition of 10% CO2 to animals breathing 10% O2 returned Pto2 to values measured while breathing 21% O2, indicating that hypercapnia can reverse the effects of acute hypoxia. Pto2 in animals acclimated to 10% O2 was similar to that measured preacclimation when breathing 21% O2. Using a novel, individualized statistical model, it was shown that the T1/2 of the Pto2 response during exposure to chronic hypoxia was approximately 2 days. This indicates a capacity for rapid adaptation to hypoxia. When subjects were returned to normoxia, there was a transient hyperoxygenation, followed by a return to lower values with a T1/2 of deacclimation of 1.5 to 3 days. These data indicate that exposure to hypoxia results in significant improvements in steady-state oxygenation for a given inspired O2 and that both acclimation and deacclimation can occur within days.

Key Words: hypoxia, brain, Pto2, oxygenation, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)

Introduction

Oxygen is a key limiting metabolite at altitude. As such, it is important to understand the mechanisms that regulate oxygen delivery and establish oxygen levels in the brain. Under acute conditions, it is known that oxygen content is not held constant, because acute reduction in the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (Pao2) or cerebral blood flow (CBF) will cause a reduction in Pto2 (Leniger-Follert et al., 1975; Hoffman et al., 1996; Nwaigwe et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2009). Increased energy demand in the brain also results in increases in Pto2 (Leniger-Follert et al., 1975), probably owing to a disproportionate increase in flow relative to metabolic rate (Kim et al., 1999).

The study investigates the response of brain Pto2 to acute and chronic hypoxia and shows changes over the time course of acclimation and deacclimation. A unique feature of this study is that brain Pto2 is monitored over time in awake animals. This was not possible in the earlier work on brain Pto2 using invasive methods, such as oxygen electrodes or fiber-optic systems (Leniger-Follert et al., 1976; Nwaigwe et al., 2000).

This study utilizes electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR, also sometimes termed electron spin resonance and abbreviated as ESR) and a chronically implanted EPR-sensitive material to measure brain Pto2 over time in the same subjects. Anesthesia can induce major changes in Pto2 (Lei et al., 2001), and its effects on Pto2 are difficult to control. EPR oximetry has the advantage of allowing for measurement of Pto2 in awake animals (Liu et al., 1993; Dunn et al., 2000; Rolett et al., 2000). The EPR line width of a crystal of lithium phthalocyanine (LiPc) is proportional to the Po2 around the crystal. This technique allows us to repeatedly measure Pto2 in the same region of brain (around an implanted crystal) over weeks.

Although acute exposure to hypoxia causes a decline in Pto2, we show that hypercapnia, through an increase in cerebral blood flow, can still serve to normalize the Pto2. We compare the effects of acute hypoxia on the pre- and postacclimated animals and utilize an individualized statistical model to analyze the time course for acclimation and deacclimation.

Material and Methods

Precalibrated lithium phthalocyanine (LiPc) crystals, possessing an EPR line width in gauss [LW(G)] that is linearly proportional to Po2, were used as the oxygen-sensitive material (Dunn et al., 2000; Rolett et al., 2000). Except for one Sprague–Dawley rat, the subjects were 150- to 200-g Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). An LiPc crystal of approximately 50 × 500 μm was implanted into the frontal cortex (2 mm posterior and 3 mm lateral to the bregma) using a 25G needle under ketamine–xylazine anesthesia (100 mg/10 mg/kg) 4 to 6 days before the first measurement of Pto2.

Intracortical LiPc placement was verified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on a 7T Magnex magnet (Oxford, England) and a Varian console (Palo Alto CA, USA). A birdcage radio frequency (RF) coil was used with a T2w spin-echo sequence. Animals were anesthetized for MRI with 1.1% isoflurane.

EPR oximetry was obtained using a low-frequency (1.18 GHz, L-band) spectrometer, using previously described methods (Nilges et al., 1990; Dunn et al., 2000). The Pto2 of each animal was calculated from the line widths of 3 to 4 EPR spectra (each consisting of four to five 7-sec scans). The method was similar to that previously reported (Dunn et al., 2000).

Awake animals were restrained in a conical plastic bag (DecapiCone, Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA, USA), and inspired gas (premixed from Airgas, Murrysville, PA, USA, at ±1% of the component gas) was delivered at 2 L/min through Tygon (St. Gobain, Paris, France) tubing. To take advantage of the full potential of EPR as a relatively noninvasive method, we minimized interventions by not collecting physiological data such as blood pressure or blood samples. Animals were acclimatized for handling and restraint by being handled and placed in restrainers for each of 2 to 3 days before the study.

Study 1

Preacclimation oximetry was conducted three times over 3 days before hypobaric hypoxia acclimation while the animals breathed 21% followed by 10% O2. After changing gases, cerebral Pot2 took 5 to 7 min to reach a steady state. Rats were acclimated to 1/2 atm (370 mmHg) of hypobaric hypoxia, which is equivalent to approximately 6000 m (West, 1999), in 40- gallon drums (Dunn et al., 2000) for 36 days. The chambers were returned to normobaric pressures daily for approximately 1 h for cage cleaning. EPR oximetry was conducted over days 27 to 36 of acclimation. After removal from the chambers, animals were maintained at 10% O2 to simulate inspired oxygen, which was similar to that of their acclimation condition. During EPR oximetry, these animals were first exposed to 10% O2 followed by 21% O2. The deacclimation study was done for 148 days posthypoxia.

Study 2

Study 2 was similar to study 1, but 7 time points were spaced over the acclimation period to examine the time course of acclimation. The Pto2 was measured only while breathing 10% O2 to eliminate the possibility that regular increases to ambient O2 would alter the time course of acclimation. Study 2 also had a shorter deacclimation period of 14 days.

Study 3

A study of acute response to hypoxia was undertaken on 4 unacclimated rats. Pto2 was measured while breathing 21% O2, followed by 10% O2, followed by 10% O2 with 10% CO2 (all balance N2).

Individual animals had a range of preacclimation values for Pto2. To assess the time course of response, a novel statistical model taking into account the paired nature of the data was used. It was assumed that the Pto2 in each rat changed according to the exponential model

|

where a3 is positive. When a2 is >0, this model describes the decrease, and when a2 is <0, this model describes the increase of Pto2 with time. In both cases, parameter a1 estimates the asymptote, and a3 estimates the rate at which Pto2 approaches its asymptote. To characterize the rate at which Pto2 approaches the asymptote, we compute the time (days) needed to reduce Pto2 by half and the time to reduce Pto2 by 9/10 of its original value at time 0, that is, a1 + a2. Solving simple equations, we obtain the formulas T(1/2) = ln(2)/a3 and T(9/10) = ln(9/10)/a3. The lower and upper bounds for a 95% confidence interval for T(1/2) are computed as ln(2)/(a3 + 1.96*se3) and ln(2)/(a3 - 1.96*se3), respectively, where se3 is the standard error of the rate parameter. The CI for T(9/10) is computed in a similar way. The exponential function is estimated using a nonlinear mixed-effect model assuming that a1 and a2 are rat specific (two random effects) (Vonesh and Chinchilli 1997; Demidenko 2004). All calculations are made using function ‘nlme’ in S-Plus 8 (Insigtful Inc., Seattle, WA, USA).

All experimental procedures were approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

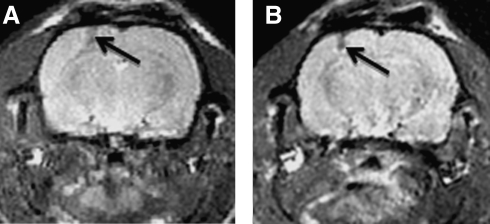

The LiPc implant site was clearly observed on MRI (Fig. 1). The tracks were elongated, so the Pto2 measured is an average in a track that extends more than 1 mm across the cortex. Animals that had implant material in the white matter were eliminated from the study because white matter Pto2 may be very different from that in the cortex.

FIG. 1.

MRI of brain with LiPc implant. MRIs were done at 7T with a spin echo sequence (TR/TE = 1000/30 s), multislice, FOV = 3 m, matrix 256 × 256. These are example MRIs from two different animals. The arrows show the needle tracks.The MRIs were used prestudy to confirm that the implant is in the cortical gray matter. MRIs were obtained between 7 and 10 days postimplant.

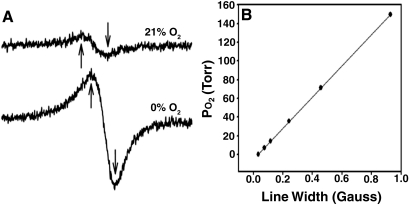

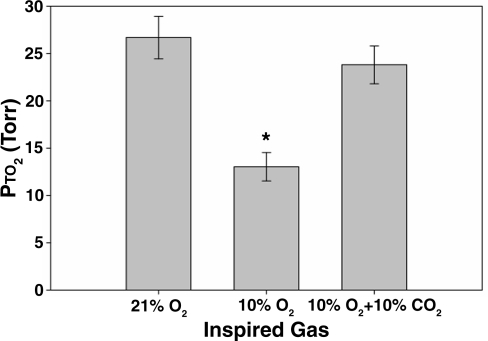

An example calibration curve of the LiPc shows the linearity of the curve (Fig. 2). In vivo brain Pto2 measurements in the cortex of the rat were 17.9 ± 3.3 mmHg, 13.9 ± 2.3 mmHg, and 26.7 ± 2.2 mmHg (mean ± SD), respectively, in studies 1 and 2 and when assessing the acute response to CO2 (Figs. 3 through 6). When the inspired gas was reduced from 21% to 10% (by 52%), the Pto2 declined by 54%, 49%, and 51% in the three studies, respectively (Figs. 3 and 6). The addition of 10% CO2 to the hypoxic breathing gas resulted in the Pto2 returning to a value not significantly different from that measured when breathing 21% O2 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

EPR calibration. (A) Example EPR line shapes measured while gases of the indicated O2% were presented to the LiPc crystal. The line width of the EPR spectrum becomes narrower as the oxygen levels decrease. Arrows indicate the points used to calculate line width with a curve-fitting program. The scale of the lower curve (0% O2) has been multiplied ×25 for better visualization. (B) Example calibration curve of a crystal of LiPc. Each point is the measured line width obtained in the presence of a different O2 concentration. The Po2 is shown on the y- axis so that, in the resulting calibration equation, the Po2 can be obtained from a measured line width during the study without transforming the linear equation.

FIG. 3.

Brain Pto2 during acute exposure to hypoxia and hypoxia + hypercapnia in awake restrained animals (mean ± SD, n = 4). * Pto2 declined significantly while breathing 10% O2. There was no significant difference between the Pto2 measured while breathing 21% O2 and that measured while breathing 10% O2 with 10% CO2 (ANOVA, with a Tukey-B post hoc test, p < 0.05).

FIG. 6.

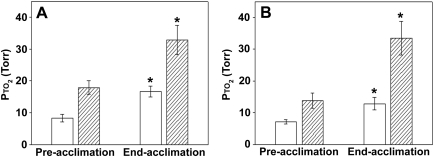

Average brain Pto2 values during inhalation of 21% and 10% O2 before and after acclimation to 11/2 atm in study 1 (A) and study 2 (B). Open bars, 10%; hatched bars, 21%. (A) Data are combined from measurements on three separate dates before acclimation to obtain preacclimation values and three dates ranging over 27 to 36 days of acclimation to obtain end-acclimation values (mean ± SD, n = 6). (B) Data are combined from measurements on two dates before acclimation. Data from the last day of acclimation are used for the end acclimation. *Denotes significant difference from respective preacclimation values. There is no significant difference between the Pto2 measured while breathing 21% before acclimation and that measured while breathing 10% after acclimation in either study 1 or study 2 (ANOVA, with a Tukey B post hoc test, p < 0.05).

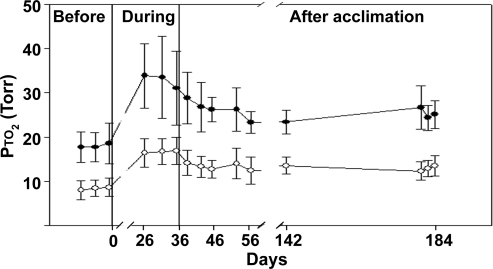

The Pto2 increased significantly during acclimation for a given inspired O2 (Figs. 5 and 6). Figure 4 shows study 1 in which Pto2 was measured before acclimation, at the end of acclimation, and then during a long time course of recovery. At the end of acclimation, animals had a Pto2 of 32.8 ± 8.0 mmHg and Pto2 of 16.7 ± 2.9 mmHg while breathing 21% O2 and 10% O2, respectively. The average decline in Pto2 for a 50% reduction in inspired O2 was 49% at the end of acclimation.

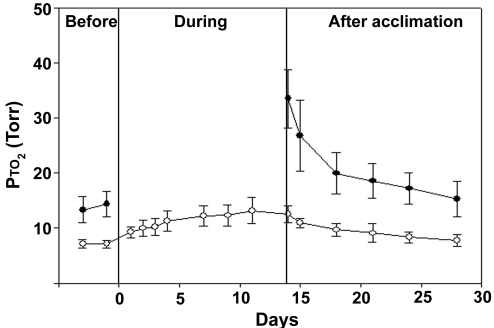

FIG. 5.

Time course of brain Pto2 values during inhalation of 21% and 10% O2 before, during, and after acclimation to 1/2 atm barometric pressure (study 2). All measurements were obtained under normobaric conditions while breathing either 21% O2 (closed circles) or 10% O2 (open circles). The pressure in the chamber was ambient during the before and after time points. The chamber was depressurized to approximately 1/2 atm (see Methods) during acclimation. This study (vs. Fig. 4) quantified the changes while breathing 10% O2 during the time course of acclimation and over a shorter recovery period (mean ± SD, n = 7).

FIG. 4.

Time course of brain Pto2 values during inhalation of 21% and 10% O2 before, during, and after acclimation to 1/2 atm barometric pressure (study 1). All measurements were obtained under normobaric conditions while breathing either 21% O2 (closed circles) or 10% O2 (open circles). The pressure in the chamber was ambient during the before and after time points. Data obtained during acclimation were in an acute normobaric condition. The animals were living in a chamber depressurized to approximately 1/2 atm and were acutely depressurized and maintained at either 21% or 10% O2 (see Methods). Note that the x-axis is nonlinear, with the acclimation data being collected at days 27, 32, and 36 of acclimation (mean ± SD, n = 6; ANOVA, with a Tukey-B post hoc test, p < 0.05).

Study 2 (Fig. 5) provided additional information about the time course of changes in Pto2 during acclimation. Here, animals were studied while breathing 10% O2 during a time course through the acclimation period, and a shorter recovery period was examined. Measurements were not done at 21% during acclimation to eliminate any possible confounding effect of repeated exposure to high O2.

The average change in Pto2 with acclimation is shown in Fig. 6, which gives the Pto2 values before and at the end of acclimation. Both studies gave similar results in that the Pto2 while breathing 10% O2 was not significantly different after acclimation from that measured while breathing 21% O2 before acclimation. Neither the pre- nor the end acclimation Pto2 values are significantly different between studies 1 and 2.

In study 1, the calculated T1/2 for recovery of Pto2 during deacclimation (while breathing 21% O2) was 3 days. The 90% recovery was achieved between 5 and 9 days in both studies although, if the 95% confidence interval is added, the lower range is 3.4 to 9 days and the upper limit is 9 to 14 days (Table 1). The Pto2 at the end of the recovery period (148 days) remained statistically higher than that measured before acclimation.

Table 1.

Response Times of Changes in Pto2 Observed for the Population during Acclimation and Recovery from Exposure to Chronic Hypoxia in Study 1 and Study 2

| |

Gas breathed during measurements |

|

|---|---|---|

| |

21% O2 |

10% O2 |

| Study 1 (n = 6) | Days | Days |

| T1/2 deacclimation | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| T1/2 95% confidence interval | 1.0–4.6 | 0.03–2.8 |

| T90% deacclimation | 9.1 | 4.8 |

| T90% 95% confidence interval | 3.4–14.8 | 0.1–9.5 |

| Study 2 (n = 7) | ||

|---|---|---|

| T1/2 acclimation | Not done | 2.1 |

| T1/2 95% confidence interval | 1.5–3.5 | |

| T90% acclimation | Not done | 7.0 |

| T90% 95% confidence interval | 5.0–11.7 | |

| T1/2 deacclimation | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| T1/2 95% confidence interval | 1.4–2.8 | 1.8–5.4 |

| T90% deacclimation | 6.1 | 8.9 |

| T90% 95 confidence interval | 4.5–9.4 | 5.9–18.0 |

In study 1, the hypoxia acclimation period was 38 days and in study 2 it was 14 days. The model uses an exponential fit to individual responses (see Methods), and the data show the response times in days for data obtained with each of the two breathing gases. High oxygen was not used during study 2 to eliminate the chance that repeated exposure to high O2 would alter the time course for acclimation.

In study 2, time-course data were also obtained during acclimation. The T1/2 for acclimation was 2 days with 90% of the change measured while breathing 10% Fio2 occurring by 7 days. The 95% confidence intervals for 90% acclimation to hypoxia were 5 to 12 days. A consistent trend was that the T1/2 for either acclimation or deacclimation was on the order of 2 to 3 days.

Discussion

Pto2 measurements

EPR oximetry can be used to provide repeated noninvasive measurements at the site of an EPR Po2 “reporter,” in this case LiPc, after the tissue has healed. Histological examination shows no inflammation after 3 to 7 days and indicates that the implant is in good contact with the surrounding tissue (Dunn et al., 2000; Rolett et al., 2000).

The absolute value of Pto2 in brain varies considerably, both spatially and temporally (Lübbers 1969; Kozniewska et al., 1987; Nwaigwe et al., 2000). Work with very fine microelectrodes indicated that Pto2 can change by tens of mmHg over micrometer distances (Lübbers, 1969). When working with large sensors, which span many capillary units, it is possible that this microheterogeneity is effectively averaged, providing a more reproducible value for Pto2 (Swartz et al., 1996). The size of the LiPc crystals in this study, up to 500 μm on one axis, would be expected to result in such averaging.

Pto2 in brain during normoxia and acute hypoxia

The three studies resulted in three values for normoxic cortex ranging from 14 to 27 mmHg. Although interventions such as hypoxia and anesthesia cocktails can predictably reduce Pto2 in brain (Lei et al., 2001), the absolute value of Pto2 varied among the studies in this paper, even though the studies were done under similar conditions. The range was similar to that previously reported (Leniger-Follert et al., 1976; Dunn et al., 2000), but it indicates that there are additional variables to be controlled. One variable will be the depth of measurement in the cortex. The capillary density, which has an effect on Pto2, varies by as much as 50% between layers II and VI in the cortex (Boero et al., 1999). It is unlikely that the chronically implanted sensors were consistent to less than 200 μm in depth. Another variable might be stress. Although these studies did reduce the effect of anesthesia, the animals were still handled during the measurements, and brain activation will increase Pto2 (Leniger-Follert and Lübbers, 1976).

This study confirms, in unanesthetized animals, the observation that Pto2 will drop significantly with an acute decline in inspired Po2 (Dunn et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2009). In mammals, a decline in Fio2 of 50% would be similar in the reduction of oxygen delivery to that which occurs with ascent to approximately 1/2 atm pressure at an elevation of approximately 6000 m, depending on latitude.

The average Pto2 in the brain of unanesthetized rats while breathing 10% O2 was measured in three studies, and the mean values ranged from 7 to 13 mmHg. This is in the range of the value of 9 mmHg noted as being a critical level for maintenance of intracellular pH during acute hypoxia (Rolett et al., 2000), a critical value of 8.5 mmHg related to 50% jugular bulb saturation (Kiening et al., 1996), and a value of <10 mmHg, which results in a poor neurological outcome (Dings et al., 1998). Adaptation is rapid, and the Po2 measured while breathing 10% O2 increases within a few days to a value that can be tolerated over the long term.

Although we did not measure CBF, we were able to indirectly determine that there was additional capacity to increase CBF and thereby improve Pto2. An increase in the concentration of CO2 increases CBF (Bereczki et al., 1993). The change in flow is likely to relate to the change in perivascular pH (Kontos et al., 1977; Apkon and Boron 1995). Perivascular acidosis will cause an increase in CBF. An increase in the inspired CO2 to 10% resulted in a significant increase in Pto2 to that approximating the “normoxic” range (Fig. 3). During normoxia, breathing 5% CO2 can result in a 13% to 47% increase in CBF (Kim et al., 1999; Ainslie et al., 2005). Breathing 10% CO2 can stimulate CBF by 81% to 240% (Dutka et al., 2002). This stimulation is very strong. Although the mechanism of CBF regulation in hypoxia differs from that during hypercapnia, it is clear that there remains a flow capacity that is untapped at this level of acute hypoxia. This is evidence that hypoxia-induced low levels of Pto2 can be improved with acute hypercapnia.

The effect of CO2 on CBF will change over time with hypoxia exposure. Immediately upon hypoxia exposure, there is a hypoxia-driven increase in CBF, while the associated hyperventilation causes a decline in Paco2, which may limit the magnitude of the increased CBF. If hyperventilation persists, then, although Paco2 remains low, there is a shift in the cerebrospinal fluid pH (and probably perivascular pH) toward normal (Severinghaus et al., 1966), which increases the sensitivity of CBF to CO2.

Changes in Pto2 with acclimation

Acute reduction of inspired O2 from 21% to 10% before acclimation resulted in an approximately 50% reduction of Pto2. This shows that this proportionality remains constant before, during, and after acclimation. Also, these studies show that at any given level of inspired gas, brain Pto2 is higher after acclimation to hypoxia, which is consistent with a previous study measuring brain Pto2 while breathing only 21% O2 (Dunn et al., 2000). In both acclimation studies, the data obtained during acclimation have a component of an acute normobaric study in that the animals were returned to normobaric pressures before measurements. Any potential stress associated with this process is not thought to have a significant influence on Pto2; a previous study in which the Pto2 was measured 24 h after removal from the chamber reported a similar increase (Dunn et al., 2000).

The specific physiological factors that result in the maintenance of Pto2 are complex. Chronic hypoxia increases the p50 of hemoglobin in humans, which results in an increase in Pto2 (Curtis et al., 1997), but this is unlikely to occur in rats (Baumann et al., 1971; Turek et al., 1972; Monge and Leon-Velarde, 1991; LaManna et al., 1992). Vascular density and hematocrit do increase with chronic hypoxia (Opitz 1951; Miller et al., 1970; LaManna et al., 1992; Harik et al., 1995; Harik et al., 1996; Boero et al., 1999). Modeling studies indicate that changes in arterial Po2, capillarity, and hematocrit are not enough to account for the measured change in Pto2 (Grinberg et al., 2005), indicating that more information is needed to understand this regulation.

A key observation is the fact that the Pto2 in brain is identical when data are compared between the preacclimation group breathing 21% O2 and the end of acclimation group breathing 10% O2. This important evidence of the regulation of Pto2 is consistent with the existence of a set point around which brain Pto2 is regulated. Such a set point will be determined by an oxygen sensor such as HIF-1α (Jiang et al., 1996; Chavez et al., 2000).

Study 2 had a design in which animals were not exposed to 21% O2 during the time course of acclimation to eliminate repeated exposure to high oxygen as a variable during acclimation. The lack of repeated exposure appeared to have little effect compared with study 1. The Pto2 values obtained while breathing 21% and 10% O2 were not significantly different between the study groups either before or after acclimation.

Time course of acclimation and deacclimation

In a previous time-course study of hypoxia acclimation, it was shown that the maximal change in Pto2 was achieved after 7 days, but the study only had measurements at 3 and 7 days and did not use a paired analysis (Dunn et al., 2000). In the current study, significant changes occurred by 2 days. This rapid adaptation has implications for planning sojourns to altitude.

This study shows that, over days after returning to normoxia, the Pto2 values in the brain, for a given Fio2, declined to values that were similar to those measured before acclimation. In study 1, although the values approached those at preacclimation, they remained significantly elevated. With this study design, we cannot rule out the possibility that there is a drift up in Pto2 around the crystal caused by some factor other than hypoxia; but in support of this being a real change, we have previously measured a control unacclimated group for 28 days without detecting such a change (Dunn et al., 2000).

This deacclimation is likely to reflect, in part, angioregression. It is known that increased oxygen after hypoxia-induced angiogenesis will result in apoptosis in endothelial cells. This process involves Ang-2, COX-2, and the TNF-like weak inducer of hypoxia, or TWEAK (Dore-Duffy and LaManna, 2007). This group estimated that such angioregression would take 1 to 2 weeks. Since the 95% confidence intervals bracket this range, these numbers could be consistent. However, if Pto2 does reflect vessel density, then it is likely that angioregession takes place in approximately 1 week, given that the mean times for 90% recovery are 2 to 9 days. These data indicate that chronic treatment with hyperoxygenation may reduce the brain's intrinsic capacity to deliver oxygen under normoxic conditions.

Conclusions

This article is unique in that the responses of brain Pto2 to acute hypoxia are measured during a time course of acclimation and deacclimation in awake animals for which anesthesia is not a confounding factor. The brain does not maintain Pto2 in the face of acute hypoxia (10% O2), even though there may be a sufficient reserve of CBF to restore Pto2 to normal. Adaptive mechanisms initiated by hypoxia can be sufficient to cause normalization of Pto2 to prehypoxia levels. Major changes during acclimation and deacclimation occur within 2 days. Deacclimation upon return to normoxia results in reduction of Pto2, for a given Fio2, which may relate to angioregression. These data indicate that the brain is capable of rapid acclimation and deacclimantion, which has implications for traveling to altitude, for treatment of hypoxic conditions, and for understanding regulation of brain oxygenation during long-term exposure to hypoxia or hyperoxia.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by an NIH RO1 to author Dunn (EB002085), by the National EPR center (RR11602), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FIN 79260).

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests or financial ties to disclose.

References

- Ainslie P.N. Ashmead J.C. Ide K. Morgan B.J. Poulin M.J. Differential responses to CO2 and sympathetic stimulation in the cerebral and femoral circulations in humans. J. Physiol. 2005;566:613–624. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkon M. Boron W.F. (1995). Extracellular and intracellular alkalinization and the constriction of rat cerebral arterioles.[erratum appears in J. Physiol. (Lond) 1995 Aug 1; 486(Pt 3):795] J. Physiol. 484:743–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann R. Bauer C. Bartels H. Influence of chronic and acute hypoxia on oxygen affinity and red cell 2,3 diphosphoglycerate of rats and guinea pigs. Resp. Physiol. 1971;11:135–144. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(71)90018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereczki D. Wei L. Otsuka T. Hans F.J. Acuff V. Patlak C. Fenstermacher J. Hypercapnia slightly raises blood volume and sizably elevates flow velocity in brain microvessels. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:H1360–H1369. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.5.H1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boero J.A. Ascher J. Arregui A. Rovainen C. Woolsey T.A. Increased brain capillaries in chronic hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;86:1211–1219. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez J.C. Agani F. Pichiule P. LaManna J.C. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in the brain of rats during chronic hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;89:1937–1942. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis S.E. Walker T.A. Bradley W.E. Cain S.M. Raising P50 increases tissue PO2 in canine skeletal muscle but does not affect critical O2 extraction ratio. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997;83:1681–1689. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko E. Wiley; New York: 2004. Mixed Models: Theory and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Dings J. Jager A. Meixensberger J. Roosen K. Brain tissue pO2 and outcome after severe head injury. Neurolog. Res. 1998;20:S71–S75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P. LaManna J.C. Physiologic angiodynamics in the brain. Antiox Redox Signal. 2007;9:1363–1371. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J.F. Grinberg O. Roche M. Nwaigwe C.I. Hou H.G. Swartz H.M. Non-invasive assessment of cerebral oxygenation during acclimation to hypobaric hypoxia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1632–1635. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutka M.V. Scanley B.E. Does M.D. Gore J.C. Changes in CBF–BOLD coupling detected by MRI during and after repeated transient hypercapnia in rat. Magn. Reson. Med. 2002;48:262–270. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg O.Y. Hou H. Roche M.A. Merlis J. Grinberg S.A. Khan N. Swartz H.M. Dunn J.F. Modeling of the response of PtO2 in rat brain to changes in physiological parameters. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2005;566:111–118. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26206-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harik N. Harik S.I. Kuo N.T. Sakai K. Przybylski R.J. LaManna J.C. Time-course and reversibility of the hypoxia-induced alterations in cerebral vascularity and cerebral capillary glucose transporter density. Brain Res. 1996;737:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00965-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harik S.I. Hritz M.A. LaManna J.C. Hypoxia-induced brain angiogenesis in the adult rat. J. Physiol. 1995;485:525–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman W.E. Charbel F.T. Edelman G. Hannigan K. Ausman J.I. Brain tissue oxygen pressure, carbon dioxide pressure and pH during ischemia. Neurol. Res. 1996;18:54–56. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1996.11740378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B.H. Semenza G.L. Bauer C. Marti H.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 levels vary exponentially over a physiologically relevant range of O2 tension. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C1172–C1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiening K.L. Unterberg A.W. Bardt T.F. Schneider G.H. Lanksch W.R. Monitoring of cerebral oxygenation in patients with severe head injuries: brain tissue PO2 versus jugular vein oxygen saturation. J. Neurosurg. 1996;85:751–757. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.5.0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.G. Rostrup E. Larsson H.B. Ogawa S. Paulson O.B. Determination of relative CMRO2 from CBF and BOLD changes: significant increase of oxygen consumption rate during visual stimulation. Magn. Reson. Med. 1999;41:1152–1161. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199906)41:6<1152::aid-mrm11>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos H.A. Raper A.J. Patterson J.L. Analysis of vasoactivity of local pH, PCO2 and bicarbonate on pial vessels. Stroke. 1977;8:358–360. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozniewska E. Weller L. Hoper J. Harrison D.K. Kessler M. Cerebrocortical microcirculation in different stages of hypoxic hypoxia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1987;7:464–470. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1987.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaManna J.C. Vendel L.M. Farrell R.M. Brain adaptation to chronic hypobaric hypoxia in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;72:2238–2243. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.6.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H. Grinberg O. Nwaigwe C.I. Hou H.G. Williams H. Swartz H.M. Dunn J.F. The effects of ketamine–xylazine anesthesia on cerebral blood flow and oxygenation observed using nuclear magnetic resonance perfusion imaging and electron paramagnetic resonance oximetry. Brain Res. 2001;913:174–179. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02786-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leniger-Follert E. Lübbers D.W. Behavior of microflow and local PO2 of the brain cortex during and after direct electrical stimulation: a contribution to the problem of metabolic regulation of microcirculation in the brain. Pflugers Arch. 1976;366:39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02486558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leniger-Follert E. Lübbers D.W. Wrabetz W. Regulation of local tissue pO2 of the brain cortex at different arterial O2 pressures. Pflugers Arch. 1975;359:81–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00581279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leniger-Follert E. Wrabetz W. Lübbers D.W. Local tissue PO2 and microflow of the brain cortex under varying arterial oxygen pressure. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1976;75:361–367. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3273-2_42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.J. Gast P. Moussavi M. Norby S.W. Vahidi N. Walczak T. Wu M. Swartz H.M. Lithium phthalocyanine: a probe for electron paramagnetic resonance oximetry in viable biological systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5438–5442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübbers D.W. The meaning of the tissue oxygen distribution curve and its measurement by means of Pt electrodes. Prog. Resp. Res. 1969;3:112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. Wu S. Rasley B. Duffy L. Adaptive response of brain tissue oxygenation to environmental hypoxia in non-sedated, non-anesthetized arctic ground squirrels. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2009;154:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.T., Jr. Curtin K.E. Shen A.L. Suiter C.K. Brain oxygenation in the rat during hyperventilation with air and with low O2 mixtures. Am. J. Physiol. 1970;219:798–801. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.3.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge C. Leon-Velarde F. Physiological adaptation to high altitude: oxygen transport in mammals and birds. Physiol. Rev. 1991;71:1135–1172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.4.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges M. Walczak T. Swartz H. 1 GHz in vivo ESR spectrometer operating with a surface probe. Physica Medica. 1990;5:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Nwaigwe C.I. Roche M.A. Grinberg O. Dunn J.F. Effect of hyperventilation on brain tissue oxygenation and cerebrovenous PO2 in rats. Brain Res. 2000;868:150–156. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz E. Increased vascularization of the tissue due to acclimation to high altitude and its significance for the oxygen transport. Exp. Med. Surg. 1951;9:389–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolett E.L. Azzawi A. Liu K.J. Yongbi M.N. Swartz H.M. Dunn J.F. Critical oxygen tension in rat brain: a combined (31)P-NMR and EPR oximetry study. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;279:R9–R16. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinghaus J.W. Chiodi H. Eger E.I.D. Brandstater B. Hornbein T.F. Cerebral blood flow in man at high altitude: role of cerebrospinal fluid pH in normalization of flow in chronic hypocapnia. Circ. Res. 1966;19:274–282. doi: 10.1161/01.res.19.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz H.M. Dunn J.F. Grinberg O.Y. O'Hara J.A. Walczak T. What does EPR oximetry with solid particles measure–and how does this relate to other measures of pO2? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1996;428:663–670. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5399-1_93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek Z. Ringnalda B.E. Hoofd L.J. Frans A. Kreuzer F. Cardiac output, arterial and mixed-venous O2 saturation, and blood O2 dissociation curve in growing rats adapted to a simulated altitude of 3500 m. Pflugers Archiv. Eur. J. Physiol. 1972;335:10–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00586931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonesh E.F. Chinchilli V.M. Linear and Non-linear Models for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- West J.B. Barometric pressures on Mt. Everest: new data and physiological significance. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;86:1062–1066. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]