Abstract

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) is a major health problem. As for most viral diseases, current antiviral treatments are based on the inhibition of viral replication once it has already started. As a consequence, they impair neither the viral cycle at its early stages nor the latent form of the virus, and thus cannot be considered as real preventive treatments. Latent HSV1 virus could be addressed by rare cutting endonucleases, such as meganucleases. With the aim of a proof of concept study, we generated several meganucleases recognizing HSV1 sequences, and assessed their antiviral activity in cultured cells. We demonstrate that expression of these proteins in African green monkey kidney fibroblast (COS-7) and BSR cells inhibits infection by HSV1, at low and moderate multiplicities of infection (MOIs), inducing a significant reduction of the viral load. Furthermore, the remaining viral genomes display a high rate of mutation (up to 16%) at the meganuclease cleavage site, consistent with a mechanism of action based on the cleavage of the viral genome. This specific mechanism of action qualifies meganucleases as an alternative class of antiviral agent, with the potential to address replicative as well as latent DNA viral forms.

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) is a major health problem with substantial impact on quality of life and disability-related costs.1 As with two other human α-herpesvirinae (namely HSV type 2 and varicella-zoster virus), HSV1 is able to become latent in neurons before inducing recurrent infections in peripheral tissues. The primary infection, asymptomatic in >90 % of cases,2 takes place in the oral mucosae, as a consequence of contact with infected particles in saliva. After replication in epithelial tissues, viruses propagate in neurons before becoming latent. Following various triggering factors, HSV1 may reactivate and thus reinvade the peripheral tissues connected to the reactivated neuron. Since the principal location of latent HSV1 is the trigeminal ganglion (TG), responsible for sensory innervation of the face, most recurrences are located in the eyes or the lips. The seroprevalence of HSV1 in the general population ranges from 24.5% to 67%, with 15 to 45% of positive subjects experiencing recurrent herpes labialis.1 The eye, and particularly the cornea, is the second most frequent location of HSV1 infection. The prevalence of herpes simplex keratitis is 149/100,000,3 with >30 new events per 100,000 inhabitants annually.4 As a consequence, HSV1 is a leading cause of blindness throughout the world. In addition, despite the use of topical or oral antiviral agents, herpes simplex keratitis remains the most frequent cause of infectious corneal opacities in the most developed areas of the world,5 accounting for about 10% of patients undergoing corneal transplantation.6 Moreover, the natural risk of HSV1 reactivation in recently grafted cornea is about 25% in the first year following surgery.7 Today, HSV1 remains a major cause of corneal graft failure, accounting for about 22% of all cases of regrafting.8

To date, commercially available anti-HSV1 agents are able to inhibit viral replication through an inhibition of the DNA-polymerase,9 meaning that any reduction in the bioavailability of the drug and/or the sensitivity of the virus may result in treatment failure. Moreover, current treatments do not reduce the load of the DNA matrix, and thus are unable to reduce the risk of further viral reactivation. Ideally, an ultimate weapon against HSV1 infection should be durably present in the cells, avoid questions of sensitivity and, if possible, reduce the load of viral genomes. Very specific endonucleases such as zinc finger nucleases10,11 or meganucleases12,13 could be used to address these goals, especially if they are delivered by a gene transfer process.

With the aim of a proof of concept study, we assessed anti-HSV1 activity in cells transfected with meganuclease-encoding plasmids. Meganucleases are endonucleases that recognize large (>12 bp) DNA sequences. In nature, they induce the spreading of mobile genetic elements by a process called homing,14 and are therefore also called homing endonucleases. Homing endonucleases have also been used to stimulate targeted recombination in immortalized mammalian cells15,16 and in various cell types and organisms (for review see ref. 13). Moreover, homing endonucleases with tailored specificities can be engineered17,18,19,20,21,22,23 and redesigned homing endonucleases targeting the human XPC and RAG1 genes have been described previously.24,25,26

In this report, we used both an I-SceI natural meganuclease and a set of redesigned meganucleases derived from I-CreI, to cleave a recombinant rHSV1 virus and/or a wild-type strain of HSV1. Our results demonstrate that HSV1-specific meganucleases can have a significant inhibitory effect on HSV1 infection at low and moderate multiplicities of infection (MOIs) (i.e., 10−3 to 1). Furthermore, this inhibition is associated with a high rate of mutation in the viral genome, at the meganuclease cleavage site, consistent with a mechanism of action based on virus clipping.

Results

Engineering of meganucleases recognizing sequences from the HSV1 virus

We have described in a series of previous reports the engineering of redesigned meganucleases targeting human genes.17,24,26,27 Briefly, we have gathered a proprietary collection (called omegabase) of >30,000 engineered endonucleases, derived mostly from the I-CreI meganuclease, and used these proteins as “building blocks” in a combinatorial process to create novel endonucleases with chosen specificities. This process, allows us to create endonucleases that cleave sequences from virtually any gene. Furthermore, although I-CreI derivatives are based on a dimeric scaffold, the engineered endonucleases can be transformed into single chain molecules, by fusing the two monomers through a peptidic linker. Single chain design can improve specificity, and enhance efficacy over a broad dose range.28 All the meganucleases used in this study are single chain versions.

In order to design meganucleases cleaving HSV1 sequences, we first identified a series of “hits” or potential targets, i.e., patchworks of sequences cleaved by proteins from Omegabase, in the HSV1 genome. Altogether, 546 such “hits” were found along the entire genomic sequence (NC_001806 from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Six of them were selected as final targets, including four in the 9 kb latency region. Functional meganucleases could be obtained for four of these six targets. These proteins, described in Table 1, are called HSV1m1, HSV1m2, HSV1m4, and HSV1m12 and the position of their target sites HSV1t1, HSV1t2, HSV1t4, and HSV1t12 is shown in Figure 1a. The HSV1m4 and HSV1m12 meganucleases recognize two distinct sequences in the ICP0 gene, which encodes a protein (infected cell protein 0) that plays a central role in viral reactivation and/or viral growth at low MOIs.9 Since this gene is duplicated, both proteins have two recognition sites in the HSV1 genome. In contrast, HSV1m1 and HSV1m2 each have a single target site, in US2, an envelope associated protein, and in UL19, a major capsid component, respectively.

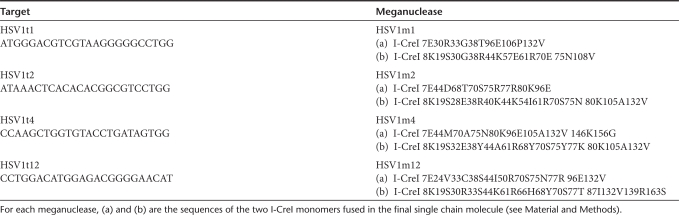

Table 1. Anti-HSV1 target sequences and meganucleases.

Figure 1.

Characterization of anti-herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) meganucleases. (a) Schematic representation of the HSV1 genome with the position of recognition sites for meganucleases HSV1m1, m2, m4, and m12 indicated. The overall structure of the HSV1 genome is shown with the unique long (UL) and unique short (US) regions, the TRL and TRS terminal repeats regions, and the IRL and IRs inverted internal repeat regions. (b and c) Cleavage activity in an extra-chromosomal functional assay in CHO-K1 cells for HSV1m1, HSV1m2, HSV1m4, and HSV1m12 compared to I-SceI and RAG1m meganucleases as positive controls. HSV1t1, HSV1t2, HSV1t4, HSV1t12, I-SceIt, and Rag1t represent cleavage activity in the absence of meganucleases. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the error bars represent standard deviation. (d) Evaluation of the toxicity of meganucleases by a cell survival assay in CHO-K1 cells. Various amounts of plasmid expressing HSV1m1, HSV1m2, HSV1m4, or HSV1m12 and a constant amount of plasmid encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) were used to cotransfect CHO-K1 cells. Cell survival is expressed as the percentage of cells expressing GFP 6 days after transfection, as described in Materials and Methods. I-SceI and RAG1m meganucleases are shown as a control for nontoxicity and I-CreI is shown as a control for toxicity.

Characterization of anti-HSV1 meganuclease activity and toxicity

The activity of the anti-HSV1 endonucleases was characterized with a previously described cell based assay,27 which directly monitors meganuclease-induced tandem repeat recombination in living cells (Figure 1b). We used as positive controls the I-SceI meganuclease, which has been used to induce highly efficient genome engineering by a large number of groups,13 and RAG1m, a previously described meganuclease shown to induce up to 6% of recombination at the RAG1 locus in cultured cells.28 HSV1m4 and HSV1m12 displayed very similar levels of activity, matching the activity of I-SceI and RAG1m, and HSV1m1 proved slightly less active (Figure 1c). However, HSV1m2 displayed a markedly different profile, with maximal activity being observed at a very low dose (0.39 ng), indicative of an extremely active protein. For comparison, the I-SceI and RAG1m proteins reached approximately the same maximal activity at a 16 times higher dose (6.25 ng) of plasmid.

Although rare cutting endonucleases are powerful tools for genome engineering, these proteins can cleave promiscuous sequences, resulting in off-site cleavage and a toxicity that can be limiting for therapeutic applications. In order to evaluate potential meganuclease toxicity, we used a previously described cell survival assay that uses green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a marker for cell viability.28,29,30 The I-SceI and RAG1m, shown to display little toxicity, if any, in a former study25,28 were used as controls as well as the wild-type I-CreI meganuclease (Figure 1d). Among the four anti-HSV1 meganucleases, HSV1m1 proved quite innocuous, with its profile mimicking the I-SceI profile. HSV1m2 behaved very similar to I-CreI, while the two other proteins displayed intermediate patterns. However, it is unclear which protein displays the best activity/toxicity ratio, as HSV1m2 is also significantly more active than I-SceI, RAG1m, and the other anti-HSV1 meganucleases (see above).

Generation of a marked recombinant HSV1 virus containing an I-SceI cleavage site

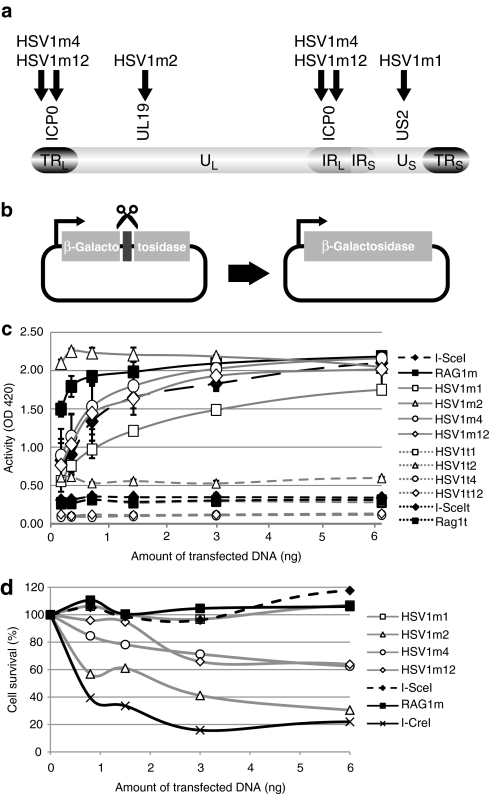

Among rare cutting endonucleases, the I-SceI meganuclease remains today the gold standard in terms of activity and specificity.13 Therefore, in order to compare the antiviral efficacy of our engineered meganucleases with this widely recognized benchmark, we built a recombinant HSV1 virus (rHSV1), containing a LacZ reporter gene with an I-SceI site between the LacZ ORF and its promoter (Figure 2a). The I-SceI cleavage site does not interfere with β-galactosidase expression. The recombinant virus was built by homologous gene targeting into the latency-associated transcript region. However, since this sequence is duplicated, two kinds of insertions can be expected (Figure 2a). Molecular combing, a powerful technique enabling the direct visualization of individual molecules, was used to determine the structure of the rHSV1. Basically, individual molecules of high molecular weight DNA are “combed” on a silanized glass coverslip, hybridized with different DNA probes31 and examined by microscopy. We applied molecular combing to uniformly stretch rHSV1 DNA extracted from viral particles and hybridized the resulting combed rHSV1 DNA with labeled adjacent and overlapping HSV1-specific DNA probes and a LacZ probe. Immunofluorescence microscopy exhibited 955 multicolor linear patterns that fulfilled the criteria for evaluation (Figure 2b). 94.6 % of these patterns (n = 903) showed two LacZ signals within the H1 and H3 regions, showing that insertions are present in both the terminal repeat region (TRL) and inverted internal repeat region (IRL) of the rHSV1 genome. In contrast, only a few signal patterns exhibited a single LacZ signal: 4.3% (n = 41) and 1.1% (n = 11) in the IRL region and the TRL region, respectively. Thus, the vast majority of recombinant HSV1 molecules in our viral preparation display two inserts.

Figure 2.

Construction and characterization of the recombinant herpes simplex virus type 1 virus (rHSV1). (a) Genomic structure of rHSV1. The overall structure of the HSV1 genome is shown with unique long (UL) and unique short (US) regions and the TRL/IRL and TRS/IR repeats. An expression cassette containing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and the LacZ coding sequence was inserted in the major latency-associated transcript (LAT) genes by homologous recombination. The I-SceI target site was cloned between the CMV promoter and the LacZ gene. (b) Schematic representation of the rHSV1-specific barcode. Alexa 594-fluorescence H1, H3, and H5 probes are indicated by the red bars, Alexa 488-fluorescence H2, H4, and H6 probes are depicted by the green bars and the LacZ probe by a blue bar. Underneath, hybridization signals that are representative of the different observed hybridization patterns are shown. IR, inverted internal repeat region; TR, terminal repeat region.

Meganucleases can prevent the infection of cultured cells by a recombinant HSV1 virus

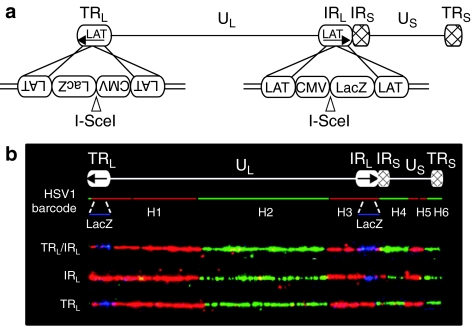

The replication competent rHSV1 virus was used to test the activity of four anti-HSV1 meganucleases in African green monkey kidney fibroblast (COS-7) cells. We first tried to identify inhibition at a low MOI, mimicking the initial steps of infection. Briefly, COS-7 cells were transfected with meganuclease-encoding plasmids at two different doses. One day later, these cells were infected at a MOI of 10−3, with the rHSV1, and viral infection was estimated 1 day postinfection using a standard β-galactosidase test. In an initial set of experiments (Figure 3a), we evaluated the effect of HSV1m1, HSV1m2, HSV1m4, HSV1m12, I-SceI, RAG1m, and HSV1m4.4, a meganuclease related to HSV1m4, but recognizing only one half of the HSV1t4 target. As expected, no infection inhibition was observed with the RAG1m and HSV1m4.4 meganucleases. In contrast, an inhibitory effect was observed with HSV1m2, HSV1m4, HSV1m12, and I-SceI. HSV1m1 had virtually no impact on infection. Western Blot performed with extracts of the transfected COS-7 cells indicates that this protein was expressed at a lower level than the three other anti-HSV1 meganucleases (Figure 3b), and thus may partially explain the lack of activity observed. The reduced levels of HSV1m1 protein may result from altered transcription, mRNA stability, mRNA translation, or protein stability due to differences in the coding sequence as has been previously shown with GFP variants.32

Figure 3.

Meganuclease-mediated inhibition of infection by recombinant herpes simplex virus type 1 virus (rHSV1). (a) COS-7 cells were transfected with various amounts (0.3 and 5 µg) of empty vector or meganuclease expressing plasmids, and infected 24 hours later with rHSV1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10−3. The level of infection was assessed 24 hours later with a β-galactosidase activity test, as described in Materials and Methods. The relative β-galactosidase activity (in %) compared to samples transfected with the empty vector is indicated. Four anti-HSV1 meganucleases were tested with several controls. HSV1m4.4 (20 kDa) is an homodimeric variant of HSV1m4. (b) Meganuclease (37 kDa) expression levels were analyzed in COS-7 cells by western blotting at 24 hours after transfection with various amounts of plasmid (0.3 and 5 µg). Antibody against β-tubulin (50 kDa) was used for the loading control. (c and d) HSV1m2, HSV1m4, and HSV1m12 meganucleases were tested at increased MOIs. A single concentration (5 µg) of meganuclease expression plasmid was introduced in COS-7 cells and infected 24 hours later with rHSV1 at a MOI of 10−3, 10−2, or 10−1. Viral load was monitored by a β-galactosidase activity test (c) and by quantitative PCR (d). Results are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation. *Statistical significance, P < 0.05.

To further characterize the antiviral potential of the HSV1m2, HSV1m4, and HSV1m12 meganucleases under more stringent conditions, cells were infected at MOIs of 10−3, 10−2, and 10−1. In order to directly evaluate the effect of the meganuclease on viral DNA production, a quantitative PCR assay (Figure 3d) was performed in addition to a β-galactosidase activity test (Figure 3c). LacZ monitoring detected a significant inhibition of viral infection with HSV1m2, HSV1m4, and HSV1m12 at a MOI of 10−3 and 10−2 (Figure 3c). However, this effect was no longer visible at a MOI of 10−1, likely due to saturating levels of LacZ activity at elevated levels of infection. In contrast, a significant reduction in viral DNA was detected for the three anti-HSV1 meganucleases by quantitative PCR in all conditions, with up to 61% of reduction of viral load at a MOI of 10−1 (Figure 3d). In addition, viral inhibition is not specific to rHSV1 as similar experiments performed with wild-type HSV1 resulted in an equivalent reduction in viral DNA as determined by quantitative PCR (data not shown).

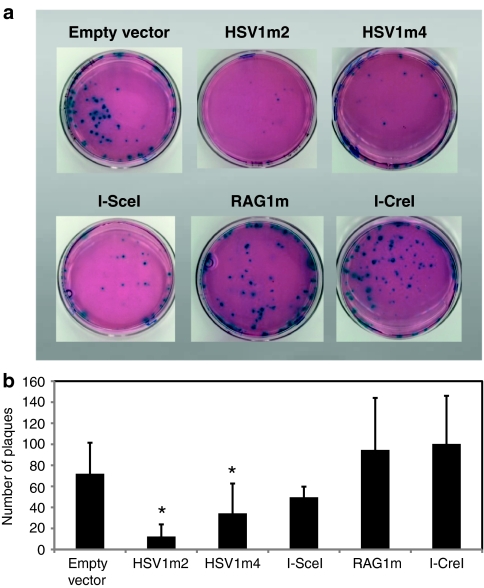

To further evaluate the ability of meganucleases to inhibit viral replication a plaque assay was performed. In this assay COS-7 cells were transfected with a control plasmid or a meganuclease-encoding plasmid, 1 day later, cells were infected with rHSV1 at a MOI of 10−3 and 2 days postinfection the number of plaques formed was determined after staining with X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β--galactopyranoside). A dramatic reduction in the formation of plaques was observed with both HSV1m2 and HSV1m4 (Figure 4a,b), indicating that both of these meganucleases are able to effectively inhibit viral replication. In contrast, no reduction in plaque formation was observed with two nonrelevant meganucleases, RAG1m, and wild-type I-CreI. These results indicate that inhibition of viral replication is specific to the anti-HSV1 meganucleases. In addition, the absence of inhibition with wild-type I-CreI, which displays a toxicity profile similar to that of HSV1m2 (Figure 1d), indicates the antiviral activity observed with the anti-HSV1 meganucleases is not due to a general toxicity effect.

Figure 4.

Prevention of recombinant herpes simplex virus type 1 virus (rHSV1) infection by HSV1m2 and HSV1m4. Cos-7 cells were transfected with 8 µg of empty vector or meganuclease expressing plasmids, and infected 24 hours later with rHSV1 at a MOI of 10−3, as described in Materials and Methods. (a) The β-galactosidase positive “blue” plaques were assessed 2 days later as described in Materials and Methods. (b) The average number of “blue” plaques detected in three independent experiments is indicated. Error bars represent standard deviation. *Statistical significance, P < 0.05.

Meganucleases prevent infection of cultured cells by a wild-type HSV1 virus

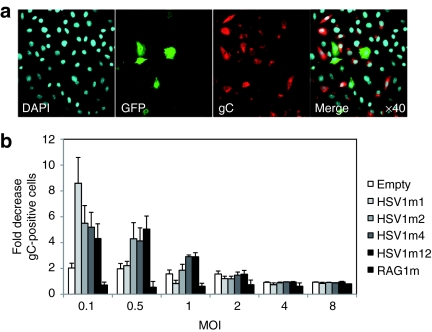

To determine if anti-HSV1 meganucleases were also active on a wild-type HSV1 virus, their antiviral activity was assessed in BSR cells with the wild-type SC16 strain of HSV1. Since the results obtained above suggested that anti-HSV1 meganucleases had a strong antiviral effect, we raised the virus dose in this experiment, using several MOIs ranging from 0.1 to 8. Briefly, BSR cells were cotransfected with GFP and meganuclease-encoding plasmids. Two days later, cells were infected at different MOIs and 8 hours postinfection the ratio of infected cells among transfected (GFP+) and nontransfected (GFP−) cells was determined (Figure 5a,b). Infected cells were identified using an antibody against the viral envelope glycoprotein C of HSV1.

Figure 5.

Meganuclease-mediated inhibition of infection by a wild-type herpes simplex virus type 1 virus (HSV1) virus in BSR and COS-7 cells. (a) BSR cells were cotransfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and meganuclease expression plasmids. Two days later, cells were infected with wtHSV1 at an MOI of 1 and 8 hours postinfection cells were fixed and analyzed by immunocytochemistry. Infected cells were detected with an antibody recognizing the gC viral glycoprotein while GFP was used to as a marker for meganuclease transfection. (b) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was used to monitor the number of GFP+ HSV1+, GFP+ HSV1−, GFP− HSV1+, and GFP− HSV1− cells. The level of infection inhibition was determined as the following ratio: (number of HSV1+ GFP− cells/number of GFP− cells)/ (number of HSV1+ GFP+ cells/number of GFP+ cells). Results are the average of six (HSV1m2 and control) or three (others) independent experiments. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

As shown in Figure 5b, a two to fourfold inhibitory effect was observed at MOIs of 0.1 and 0.5. However, this effect disappeared (compared to negative control) by a MOI of 1. The HSV1m1 meganuclease, which was found to be inefficient in a previous assay (Figure 3a), displayed a high efficacy in this assay at a MOI of 0.1. This discrepancy can be attributed to a difference in the sensitivity of the assays: indeed, the β-galactosidase assay used in Figure 3a,c seems to be less sensitive than the quantitative PCR assay (compare Figure 3c,d, at high MOIs), and the immunodetection assay (compare Figures 3c,5b at MOI = 0.1). It is unclear why, with the immunodetection assay, HSV1m1 has the highest impact at a MOI of 0.1. However, in accordance with previous results, this meganuclease appears to be less potent as its activity is no longer detected at a MOI of 0.5 (Figure 5b).

In addition, the effects observed appear to be specific to anti-HSV1 meganucleases since the introduction of an unrelated meganuclease, RAG1m, resulted in no detectable antiviral activity. One should also note that at a low MOI, a small but reproducible effect was observed even with the negative control, suggesting that transfection of a GFP plasmid might have an effect by itself, maybe by transiently disrupting cellular membrane metabolism.

Anti-HSV1 meganucleases induce high rates of mutations at their target site

The inhibition of HSV1 infection by the anti-HSV1 meganucleases is thought to be due to cleavage of viral DNA. Cleavage of an episomal sequence can result in its degradation and loss, but also in its repair by the endogenous maintenance systems of the cell. DNA double strand breaks can be repaired by homologous recombination or by nonhomologous end joining, two alternative mechanisms.33,34,35 Furthermore, there is an error prone nonhomologous end joining pathway that results mostly in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site.34,36,37,38 Thus, upon meganuclease inhibition of infection, the remaining viral genomes should display a detectable level of indels at the cleavage site.

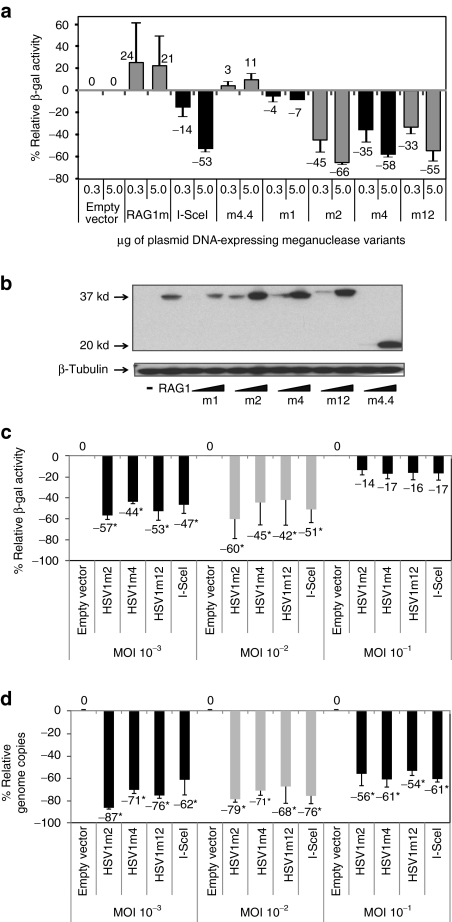

We amplified by PCR the HSV1t2 and HSV1t4 DNA regions from cells treated with the HSV1m2 and HSV1m4 meganucleases or empty vector, and used deep sequencing to characterize individual PCR products (Figure 6). In the absence of meganuclease, indels were absent or barely detectable, with no observed events for HSV1t4, and 0.05% for HSV1t2. However, mutation frequencies increased up to 2.8% in samples transfected with 5 µg of the HSV1m4 expression vector, and 16% in samples treated with 5 µg of the HSV1m2 expression vector. In both cases, deletions largely outnumbered insertions (2.5% of deletions versus 0.3% of insertions with HSV1m4, 15% of deletions and 1% of insertions with HSV1m2). As shown in Figure 6, there was also a strong bias in favor of small deletions. These results confirm that a very high rate of cleavage occurs at the meganuclease cleavage sites, and are consistent with a mechanism of inhibition based on viral DNA cleavage.

Figure 6.

Distribution and frequency of meganuclease-induced deletions and insertions (indels) in the recombinant herpes simplex virus type 1 virus (rHSV1) genome after treatment with HSV1m2 and HSV1m4. 10,356 PCR products were sequenced for HSV1t2 and, 12,228 for HSV1t4. The distribution and frequency of observed deletions or insertions is indicated. We also sequenced 23,527 PCR products for HSV1t2 and 16,961 for HSV1t4, in the absence of meganuclease treatment and found 12 events for HSV1t2 (0.05%) and, no indel for HSV1t4.

Discussion

In this report, we show that the expression of meganucleases cleaving sequences from an HSV1 virus can significantly prevent HSV1 infection in cultured cells. Three different and nonmutually exclusive mechanisms of action could explain these results. First, cleavage followed by double strand break repair by the error prone nonhomologous end joining pathway could result in mutations that would alter essential functions of the virus and prevent its efficient replication. The presence of meganuclease-induced mutations is indeed demonstrated by our results (Figure 6). As the meganuclease sites are present in coding sequences, the majority of the resulting deletions/insertions result in either frameshifts or inactivating mutations. However, it cannot be excluded that in certain cases mutations will occur that render the virus resistant to meganuclease cleavage without affecting viral fitness. Further studies examining the effect of individual mutations will be necessary to address this question. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that meganuclease-induced mutations are responsible for the largest part of infection inhibition as the I-SceI meganuclease, which is one of the most potent infection inhibitors, cleaves the LacZ reporter cassette, which is not involved in viral functions.

Second, virus cleavage could be followed by DNA degradation and clearance of the cleaved molecules. Inhibition of infection would then result from a loss of viral sequences. An unrepaired double strand break is a deadly event for a cell, for the only DNA ends that can be stably maintained in the cell, without the loss or degradation of genetic material, are the telomeres.39 Cells have evolved a series of maintenance pathways responsible for the repair of such damages.33,35 However, these repair pathways could be overwhelmed, being unable to respond to strong cleavage of the target sequence, and opening the way to the extensive resection of double strand breaks by exonucleases, as was observed for yeast chromosomes.40 The degradation or disappearance of nonreplicative episomal sequences upon cleavage by an endonuclease has been previously documented,41 and it is extremely likely that a similar effect would be observed with a latent, nonreplicative HSV1 form. Third, cleavage could interfere with viral replication, which is disconnected from the host cell's cycle. Upon infection, the viral genome adopts a circular conformation, and is replicated by a rolling circle mechanism, that is not compatible with a linearized viral form.42 Inhibition of infection would then result from a lack of amplification, or at least a decrease in the level of amplification of the viral particles initially entering the cell.

Indeed, we found that anti-HSV1 meganucleases could reduce the number of viral genome copies in infected-cells (Figure 3d) as well as block viral replication as determined by a plaque reduction assay (Figure 4a,b). Thus our findings are consistent with the inhibition of viral replication either by the linearization of replication intermediates or the direct elimination of incoming viral genomes before replication is initiated. These results illustrate a new mechanism of action, based on virus clipping, to inhibit viral infection. Recently, zinc finger nucleases, another class of very specific endonucleases, have been shown to cleave hepatitis B virus sequences present on a plasmid substrate.43 Our study expands these initial results by demonstrating the potential of meganucleases to inhibit an intact, replicating virus, and thus provide an essential proof of concept toward the use of endonucleases as antiviral agents.

In our study, efficient inhibition could be observed with MOIs ranging from 10−3 to 10−1, but not at higher doses. The first steps of viral reactivation within the TG likely involve only a very small number of neurons, as shown by experimental studies.44 However, HSV1 reactivation is a rare and self-limited event. In mice, spontaneous reactivation of the virus occurs at any given moment in about one neuron per 10 TG44 leading to an estimation of one reactivation for about 50,000 latently infected neurons. Furthermore, most of the patients with recurrent corneal herpetic disease display only dendritic epithelial keratitis,1,4 i.e., a self-limited infection of the superficial layer of the cornea, while major necrosis of the entire cornea is very rare. Taken together, these data suggest that the early steps of clinical herpetic relapse are probably the consequence of only a few infectious particles emerging from TG nerve endings into corneal tissues. As a consequence, a sentinel antiviral process localized in the corneal cells, could block the viral infection in the early stages, and thus prevent the extension of a huge and devastating productive cycle of viral replication in the ocular tissues.

However, quantitative studies in relevant animal models will be necessary to determine if the levels of inhibition obtained with anti-HSV1 meganucleases are sufficient to have a significant impact on the clinical course of infection.

One of the limits to this type of strategy is the toxicity that could result from long-term expression of the meganucleases in the target cells. Sustained expression can result in off-site cleavage potentially resulting in mutations or gross chromosomal rearrangements.45 One way to circumvent this kind of effect would be to control the expression of the meganuclease, and limit it to a critical period of time. Inducible meganucleases, resulting from fusions with the ligand binding domain of nuclear receptors have already been described46,47,48 and could be used for this purpose.

The use of an efficient delivery method is another prerequisite for the effective use of meganucleases as an antiviral agent. Vectorization of internal structures such as the TG might prove more difficult than delivery into external tissues or organs, such as lips and superficial ocular tissues. However, even in easily accessible tissues, the ability of meganucleases to be effectively used as a stand-alone treatment will need to be evaluated since current vectorisation techniques do not permit in vivo vectorisation of a large majority of cells. Alternatively, meganucleases could be combined with classic antiviral treatments to give a potentially synergistic effect that would provide more potent protection than current approaches. This strategy is particularly attractive for the prevention of recurrent infections during corneal transplantation. The introduction of meganucleases into the graft before transplantation may provide the additional protection necessary to successfully address the low amplitude of the initial reinfection steps. An ex vivo animal model is currently being established in order to test the effectiveness of these approaches to inhibit infection directly in corneal tissue.

Materials and Methods

Meganuclease engineering. The engineering methods used have been described before.17,26,27,28 To create single chain molecules, the two monomers forming the most active heterodimer were selected, we added mutations K7E, K96E and E8K, E61R to the first and second monomer respectively, and the two monomers were fused as described in Grizot et al.28

Evaluation of meganuclease activity in an extrachromosomal assay in mammalian cells. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with Polyfect transfection reagent (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France) in 96-well plates. 150 ng of target vector was cotransfected either with empty vector or with increasing quantities of a meganuclease expression plasmid (0.75 to 6.25 ng). Total amount of transfected DNA was completed to 175 ng with empty vector. Seventy-two hours after transfection, cells were treated with 150 µl of β-galactosidase lysis/revelation buffer (typically for 1l of buffer we use 100 ml of lysis buffer (10 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 0.1 % Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, protease inhibitors), 10 ml of Mg 100× buffer (100 mmol/l MgCl2, 35% β-mercaptoethanol), 110 ml ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactopyranoside 8 mg/ml and 780 ml of sodium phosphate 0.1 mol/l pH 7.5). After incubation at 37 °C, OD was measured at 420 nm. The entire process is performed on an automated Velocity11 BioCel platform (Velocity11, Menlo Park, CA).

Cell survival assay. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with various amounts of meganuclease expression vectors and a constant amount of GFP-encoding plasmid in 96-well plates using Polyfect transfection reagent (QIAGEN). GFP levels were monitored on day 1 and 6 after transfection, by flow cytometry. Cell survival is expressed as a percentage and was calculated as a ratio: meganuclease-transfected cell expressing GFP on day 6/control transfected cell expressing GFP on day 6, corrected for the transfection efficiency determined on day 1.

Construction of rHSV1 recombinant virus. The HSV1 strain (F1) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Teddington, UK). Viruses were propagated on immortalized COS-7 cells, obtained from ATCC. Recombinant virus (rHSV1) was generated in a manner similar to that previously described.49 An ~4.6 kb PstI-BamHI viral genomic fragment was cloned into pUC19. Based on HSV1 sequence from the database (GenBank NC_001806) this represents nucleotides 118869–123461 and 7502–2910 in the TRL and IRL repeats of the HSV1 genome. A cassette containing the cytomegalovirus promoter driving LacZ expression was introduced into a 19 bp SmaI/HpaI deletion. The I-SceI cleavage site (TAGGGATAACAGGGTAAT) was inserted after the cytomegalovirus promoter and before the ATG of the LacZ gene. This construct was linearized by XmnI digestion and 2 µg was cotransfected with 10 µg of HSV1 genomic DNA into COS-7 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Pontoise, France). After 3 days, infected cells were harvested, sonicated and used to infect a COS-7 monolayer. Cells were overlayed with 1% agarose medium and 3 days later, 300 µg/ml of X-gal was added to the overlay. β-galactosidase positive “blue” plaques were picked and subjected to three rounds of plaque purification.

Molecular combing, analysis of rHSV1 genome. 4 × 105 rHSV1 viral particles were embedded in 1% low melting point agarose and lysed in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate-0.5 mol/l EDTA (pH 8.0) solution at 50 °C for 30 minutes. After three washing steps in 0.5 mol/l EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer, agarose plug-embedded viral particles were digested by overnight incubation at 50 °C with 2 mg/ml Proteinase K (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) in digestion buffer (0.5 mol/l EDTA (pH 8.0)). Final DNA extraction was achieved by β-agarase I digestion (1.5 units; New Enlgand Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in 0.5 mol/l of 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (pH 5.5) at 42 °C for up to 16 hours. The DNA solution was then poured into a Teflon reservoir and combed on silanized glass cover slips as described previously.31 Probes were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (LacZ), biotin-11-dCTP (H1, H3, and H5) or Alexa488-7-OBEA-dCTP (H2, H4, and H6) by random priming with BioPrime DNA kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridization and multilayer antibodies revelation was performed as described previously.31 For data evaluation, only fluorescent in situ hybridization signal arrays composed of a continuous signal chain of Alexa 594-fluorescence for H1 and H3 and Alexa 488-fluorescence for H2 were considered.

Transfection of COS-7 cells and infection by rHSV1. COS-7 cells were seeded in six well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight at 37 °C in complete growth medium. The next day, cells were transfected with 0.3 or 5.0 µg of meganuclease expression plasmid or empty vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). In these conditions, the transfection efficiency was greater the 90% with 5.0 µg and 55% with 0.3 µg of plasmid DNA. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were infected with rHSV1 at a MOI from 10−3 to 1. Cells were harvested 24 hours after infection and β-galactosidase activity was assayed on a total of 1.0 × 103 or 2.5 × 104 rHSV1 infected-cells using a luminescent β-galactosidase assay (Beta-Glo assay, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France).

Western blot analysis. COS-7 cells were harvested 24 hours after transfection and lysed using RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA). Twenty micrograms of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated with a primary rabbit polyclonal antibody against I-CreI (1:20,000 dilution) followed by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidise (1:5,000 dilution). Specific protein bands were visualized with a chemiluminescence reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). A rabbit antibody against β-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, MA) was used for the loading control.

Quantification of viral DNA. Total DNA (COS-7 and HSV1 genomes) from transfected and infected COS-7 cells was extracted and purified using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Real-time PCR was performed using primers specific to the gB gene in the HSV1 genome (forward primer: 5′-AGAAAGCCCCCATTGGCCAGGTAGT and reverse primer: 5′-ATTCTCTTCCGACGCCATATCCACCAC) normalized to COS-7 DNA using primers specific to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (forward primer: 5′-GGCAGAACCCGGGTTTATAACTGTC and reverse primer: 5′-CCAGTCCTGGATGAGAAAGG). The PCR was carried out using SYBR Premix Ex taq (TaKaRa, Saint-Beauzire, France) and PCR amplification included initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, 60 °C for 15 seconds, and 72 °C for 30 seconds.

Plaque assay. To visualize the infection by rHSV1, transfected COS-7 cells (4 × 105) were seeded in 60-mm dishes. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were incubated with rHSV1 at a MOI of 10−3. One hour after infection, cells were washed once with medium without serum to remove input virus particles that did not enter cells, overlayed with 1% agarose growth medium and incubated at 37 °C. At 2 days postinfection, cells were overlayed with 1% agarose medium containing 0.5% of X-gal to visualize the β-galactosidase positive “blue” plaques.

Transfection of BSR cells and infection by wild-type SC16 strain of HSV1. The wild-type SC16 strain of HSV1 was propagated on BSR cells, as previously described.50 BSR cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight at 37 °C in complete growth medium. The next day, cotransfections with 1.5 µg of plasmid expressing an anti-HSV1 meganuclease and 1.5 µg of plasmid expressing GFP were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). In these conditions, the transfection efficiency was 60%. After 48 hours, cells were infected with the wild-type SC16 strain of HSV1 at a MOI varying from 0.1 to 8. Eight hours postinfection cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde at RT for 15 minutes. For analysis by microscopy, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and treated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Immunostaining was performed with (i) 1:500 dilution of rabbit antibodies against glycoprotein C (gC) of HSV1 (Clinisciences) and (ii) 1:500 dilution of phycoerythrin conjugated goat anti-rabbit IGg secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cells were analyzed either with an EPICS ELITE ESP (Beckman-Coulter, Villepinte, France) Cytometer or a Leica DMR confocal microscope with a ×40 objective. The analysis by cytometer was performed on a total of 1 × 104 cells.

PCR and sequencing analysis of rHSV1 genome. COS-7 cells were transfected with 5 µg of meganuclease expressing plasmids, and infected 24 hours later with rHSV1 at a MOI of 10−3. Twenty-four hours after infection total DNA (COS-7 and rHSV1 genomes) was recovered and analyzed using a pair of tag-forward and biotin-labeled reverse PCR primers recognizing a part of the rHSV1 genome corresponding to sequences recognized by meganucleases HSV1m2 and m4. PCR reactions were run for 30 cycles with an annealing temperature of 67 °C. Gel purified PCR products were sent to GATC Biotech (Mullhouse, France) for sequence analysis.

Statistical analysis. A Kruskall–Wallis rank test was used for the immunodetection assay. Student's t-test was used for all other analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the project ACTIVE that is supported by the Strategic Industrial Innovation program of OSEO (OSEO-ISI). S.G., S.A., D.L., I.C-S., C.J., C.D., F.C., F.P., and J.S. are full time employees of Cellectis or Cellectis Genome Surgery. C.M., S.B., and E.C. are full time employees of Genomic Vision.

REFERENCES

- Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang TJ. Epidemiology of ocular herpes simplex. Natural history in Rochester, Minn, 1950 through 1982. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1160–1165. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020226030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang TJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, Daly PJ., and, Ilstrup DM. Epidemiology of ocular herpes simplex. Incidence in Rochester, Minn, 1950 through 1982. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1155–1159. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020221029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labetoulle M, Auquier P, Conrad H, Crochard A, Daniloski M, Bouée S, et al. Incidence of herpes simplex virus keratitis in France. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group THEDS Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léger F, Vital C, Négrier ML., and, Bloch B. Histologic findings in a series of 1,540 corneal allografts. Ann Pathol. 2001;21:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomholt JA, Baggesen K., and, Ehlers N. Recurrence and rejection rates following corneal transplantation for herpes simplex keratitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995;73:29–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1995.tb00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham GC, Bijwaard K, Sheng ZM, Hidayat AA, Font RL., and, McLean IW. Primary graft failure: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2083–90;discussion 2090. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickelbein JE, Hendricks RL., and, Charukamnoetkanok P. Management of herpes simplex virus stromal keratitis: an evidence-based review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH., and, Carroll D. Gene targeting using zinc finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:967–973. doi: 10.1038/nbt1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll D. Progress and prospects: zinc-finger nucleases as gene therapy agents. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1463–1468. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galetto R, Duchateau P., and, Pâques F. Targeted approaches for gene therapy and the emergence of engineered meganucleases. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1289–1303. doi: 10.1517/14712590903213669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pâques F., and, Duchateau P. Meganucleases and DNA double-strand break induced recombination: perspectives for gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2007;7:49–66. doi: 10.2174/156652307779940216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier BS., and, Stoddard BL. Homing endonucleases: structural and functional insight into the catalysts of intron/intein mobility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3757–3774. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choulika A, Perrin A, Dujon B., and, Nicolas JF. Induction of homologous recombination in mammalian chromosomes by using the I-SceI system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1968–1973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouet P, Smih F., and, Jasin M. Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8096–8106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Grizot S, Arnould S, Duclert A, Epinat JC, Chames P, et al. A combinatorial approach to create artificial homing endonucleases cleaving chosen sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuer S, Pingoud V, Pingoud A., and, Wende W. Chimeras of the homing endonuclease PI-SceI and the homologous Candida tropicalis intein: a study to explore the possibility of exchanging DNA-binding modules to obtain highly specific endonucleases with altered specificity. Chembiochem. 2004;5:206–213. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth J, Havranek JJ, Duarte CM, Sussman D, Monnat RJ, Jr, Stoddard BL, et al. Computational redesign of endonuclease DNA binding and cleavage specificity. Nature. 2006;441:656–659. doi: 10.1038/nature04818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., and, Zhao H. A highly sensitive selection method for directed evolution of homing endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastberg JH, McConnell Smith A, Zhao L, Ashworth J, Shen BW., and, Stoddard BL. Thermodynamics of DNA target site recognition by homing endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7209–7221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LE, Morrison HA, Masri S, Brown MJ, Springstubb B, Sussman D, et al. Homing endonuclease I-CreI derivatives with novel DNA target specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4791–4800. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva GH, Belfort M, Wende W., and, Pingoud A. From monomeric to homodimeric endonucleases and back: engineering novel specificity of LAGLIDADG enzymes. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grizot S, Epinat JC, Thomas S, Duclert A, Rolland S, Pâques F, et al. Generation of redesigned homing endonucleases comprising DNA-binding domains derived from two different scaffolds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2006–2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo P, Prieto J, Muñoz IG, Alibés A, Stricher F, Serrano L, et al. Molecular basis of xeroderma pigmentosum group C DNA recognition by engineered meganucleases. Nature. 2008;456:107–111. doi: 10.1038/nature07343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnould S, Perez C, Cabaniols JP, Smith J, Gouble A, Grizot S, et al. Engineered I-CreI derivatives cleaving sequences from the human XPC gene can induce highly efficient gene correction in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnould S, Chames P, Perez C, Lacroix E, Duclert A, Epinat JC, et al. Engineering of large numbers of highly specific homing endonucleases that induce recombination on novel DNA targets. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:443–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grizot S, Smith J, Daboussi F, Prieto J, Redondo P, Merino N, et al. Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5405–5419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder ML, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Osiak A, Wright DA, Anthony RM, Eichtinger M, et al. Rapid “open-source” engineering of customized zinc-finger nucleases for highly efficient gene modification. Mol Cell. 2008;31:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett-Miller SM, Connelly JP, Maeder ML, Joung JK., and, Porteus MH. Comparison of zinc finger nucleases for use in gene targeting in mammalian cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:707–717. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalet X, Ekong R, Fougerousse F, Rousseaux S, Schurra C, Hornigold N, et al. Dynamic molecular combing: stretching the whole human genome for high-resolution studies. Science. 1997;277:1518–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti A, El Sewedy T, Nasr AF., and, Alberti S. Efficient GFP mutations profoundly affect mRNA transcription and translation rates. FEBS Lett. 2001;492:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlerode AJ., and, Scully R. Mechanisms of double-strand break repair in somatic mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2009;423:157–168. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirouilh-Barbat J, Rass E, Plo I, Bertrand P., and, Lopez BS. Defects in XRCC4 and KU80 differentially affect the joining of distal nonhomologous ends. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20902–20907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708541104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pâques F., and, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez EE, Wang J, Miller JC, Jouvenot Y, Kim KA, Liu O, et al. Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:808–816. doi: 10.1038/nbt1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon JB, Pattanayak V, Meyer CB., and, Liu DR. Directed evolution and substrate specificity profile of homing endonuclease I-SceI. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2477–2484. doi: 10.1021/ja057519l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Han M, Romanienko PJ., and, Jasin M. Homology-directed repair is a major double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5172–5177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan RJ., and, Karlseder J. Telomeres: protecting chromosomes against genome instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:171–181. doi: 10.1038/nrm2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD., and, Haber JE. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F., and, Jasin M. Ku80-deficient cells exhibit excess degradation of extrachromosomal DNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14405–14411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizman, B., and, Knipe, D.2001. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In:Knipe D, Howley P, Griffin D, et al. eds) Fields Virology, 4th edn., vol. 72. Raven Publishers: Philadelphia, pp. 2399–2459 [Google Scholar]

- Cradick TJ, Keck K, Bradshaw S, Jamieson AC., and, McCaffrey AP. Zinc-finger nucleases as a novel therapeutic strategy for targeting hepatitis B virus DNAs. Mol Ther. 2010;18:947–954. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LT, Ellison AR, Voytek CC, Yang L, Krause P., and, Margolis TP. Spontaneous molecular reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:978–983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022301899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet E, Simsek D, Tomishima M, DeKelver R, Choi VM, Gregory P, et al. Chromosomal translocations induced at specified loci in human stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10620–10625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902076106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrkamp-Richter S, Degroote F, Laffaire JB, Paul W, Perez P., and, Picard G. Characterisation of a new reporter system allowing high throughput in planta screening for recombination events before and after controlled DNA double strand break induction. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou E, Dorn JF, Sengupta K, Jasin M, Nussenzweig A, Ried T, et al. Positional stability of single double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:675–682. doi: 10.1038/ncb1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N., and, Stark JM. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann RH., and, Efstathiou S. Utilization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated regulatory region to drive stable reporter gene expression in the nervous system. J Virol. 1997;71:3197–3207. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3197-3207.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labetoulle M, Kucera P, Ugolini G, Lafay F, Frau E, Offret H, et al. Neuronal propagation of HSV1 from the oral mucosa to the eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2600–2606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]