Abstract

Pancreatic acinar cells are classical exocrine gland cells. The apical regions of clusters of coupled acinar cells collectively form a lumen which constitutes the blind end of a tube created by ductal cells-a structure reminiscent of a “bunch of grapes”. When activated by neural or hormonal secretagogues, pancreatic acinar cells are stimulated to secrete a variety of proteins. These proteins are predominately inactive digestive enzyme precursors called “zymogens”. Acinar cell secretion is absolutely dependent on secretagogue-induced increases in intracellular free Ca2+. The increase in [Ca2+]i has precise temporal and spatial characteristics as a result of the exquisite regulation of the proteins responsible for Ca2+ release, Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ clearance in the acinar cell. This brief review discusses recent studies in which transgenic animal models have been utilized to define in molecular detail the components of the Ca2+ signaling machinery which contribute to these characteristics.

Keywords: pancreatic acinar cell; Ca2+ Signaling; exocytosis; Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

1. Introduction

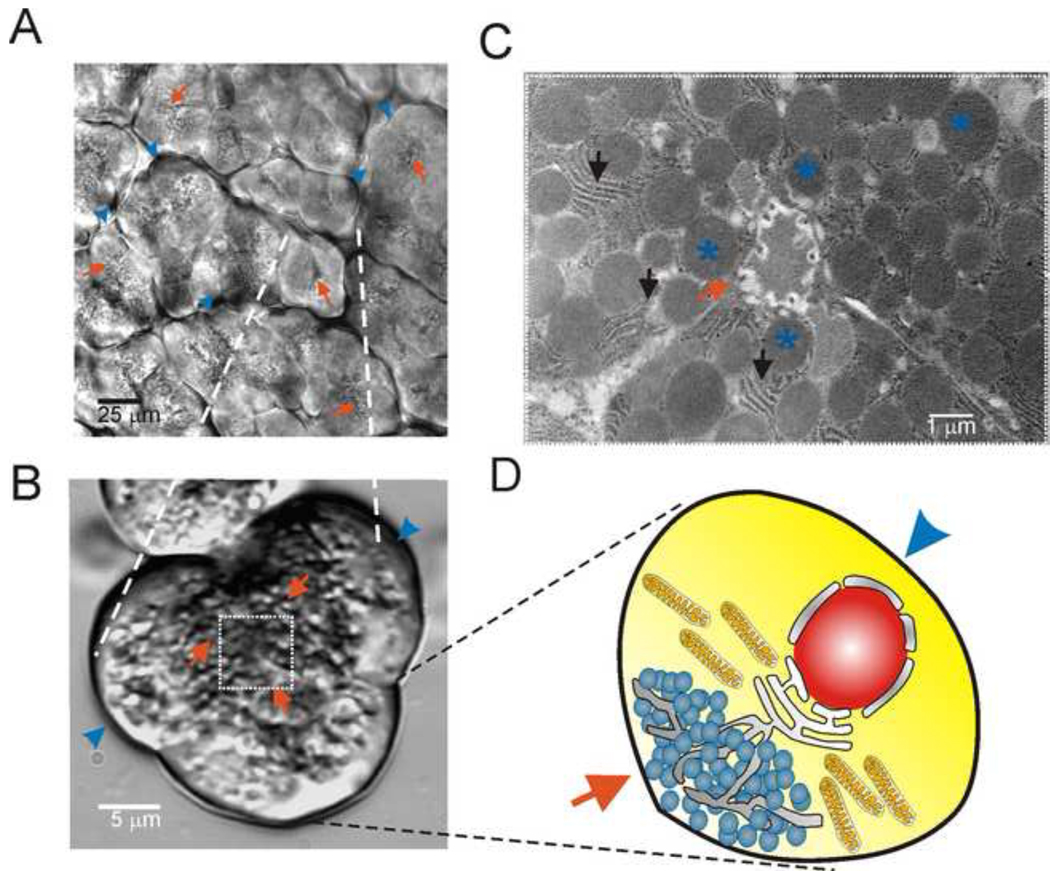

The pancreas is a mixed exocrine and endocrine tissue, physically situated as an accessory organ connected to the gut tube at the level of the duodenum. The exocrine pancreas primarily consists of two major cell types; acinar and ductal cells. Together these cells are responsible for the production of a HCO− rich solution containing a plethora of proteins which are responsible for the efficient assimilation of nutrients. While the ductal cells account for the production of the vast majority of alkaline fluid, pancreatic acinar cells are classical polarized epithelial cells and are morphologically and functionally specialized for the exocrine secretion of protein containing vesicles across the apical membrane (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pancreatic acinar cell morphology.

In A, a low magnification transmitted laser light image obtained using multi-photon microscopy of an isolated mouse pancreatic lobule. Red arrows indicate the apical, zymogen granule region and blue arrow heads highlight the basal aspects of the acinar cells in all images. In B, a DIC image of a small clump of mouse acinar cells isolated by enzyme digestion. In C, a transmitted electron microscopy image of the extreme apical aspects of an acinus is shown. The blue asterisks indicate zymogen granules and the black arrows point to ER strands. In D, a cartoon depicting a single polarized acinar cell. The nucleus is located towards the basal pole while ER strands extend into the zymogen granule region. Mitochondria are present surrounding the granular region.

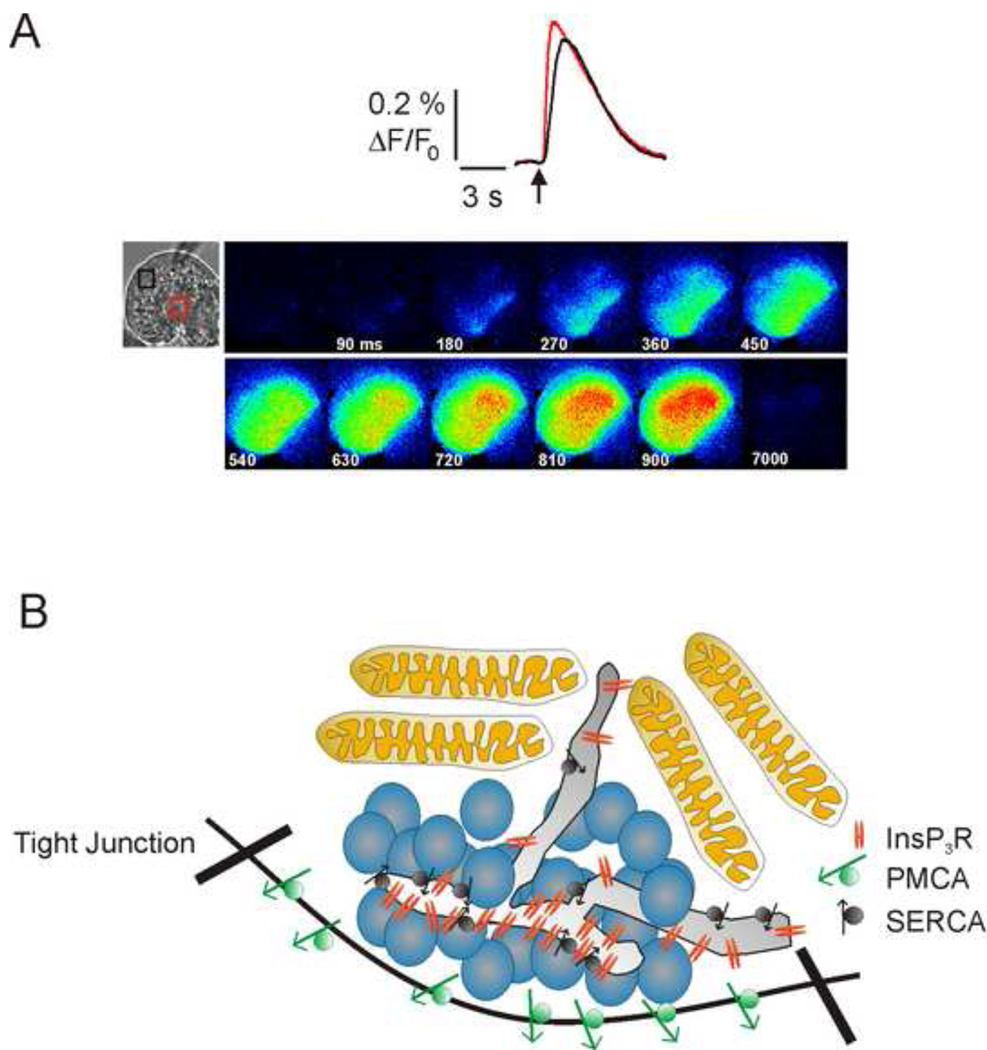

The exocytosis of secretory granules is absolutely dependent on secretagogue induced elevations in cytosolic free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) (Futatsugi et al., 2005). The important event leading to the increase in [Ca2+]i following binding of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine or gastrointestinal hormone cholecystokinin on the basolateral aspects of the acini (Figure 1) is the Gαq-stimulated increase in activity of phospholipase C, leading to the generation of the second-messenger inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate (InsP3) (Williams & Yule, 2006). Binding of InsP3 to its receptors (InsP3R), which are calcium permeable channels localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) results in Ca2+ release into the cytoplasm (Streb et al., 1983). Secretagogue stimulation also triggers Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space across the plasma membrane (PM). Contributions from both Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx are necessary for continued, sustained exocytosis of granules (Tsunoda et al., 1990). Activation of this machinery results in intracellular calcium signals with complex spatial and temporal characteristics. For example, although production of InsP3 occurs predominately at the lateral and basal membranes, Ca2+ release invariable is initiated in the extreme apical pole of the acinus where the vast majority of InsP3R are located (Figure 2) (Kasai & Augustine, 1990; Thorn et al., 1993; Nathanson et al., 1994; Yule et al., 1997). At threshold levels of stimulus, Ca2+ signals can be confined to this domain, allowing standing gradients of [Ca2+]i to be established (Kasai et al., 1993; Thorn et al., 1993). It is thought that Ca2+ uptake by a peri-granular belt of mitochondria function as a “fire-wall” to confine signals to the apical domain (Tinel et al., 1999; Straub et al., 2000). Physiological levels of agonist result in the propagation of a Ca2+ wave traveling from the initiation sites in the so called apical “trigger zone” towards the basal region of the cell (Kasai et al., 1993; Thorn et al., 1993) (Figure 2A). The Ca2+ wave relies on Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release via InsP3R and ryanodine receptors distributed on ER throughout the cytoplasm (Straub et al., 2000). In the continued presence of secretagogue, extrusion of Ca2+ across the PM and sequestration into mitochondria and the ER serves to reduce [Ca2+]i prior to the initiation of a further apical to basal Ca2+ wave (Figure 2B) (Lee et al., 1997a; Tinel et al., 1999; Straub et al., 2000). These spatial characteristics result temporally in the generation of Ca2+ spikes or oscillations (Yule & Gallacher, 1988; Yule et al., 1991). Together these stereotyped features of the Ca2+ signals are thought to be fundamentally important in the appropriate activation of effectors necessary for secretion (Maruyama et al., 1993).

Figure 2. Spatial characteristics of Ca2+ release in pancreatic acinar cells.

In A, the Ca2+ signal evoked following global flash photolysis (activation) of chemical-caged (inert) InsP3 is shown. The image series demonstrates that despite the uniform production of InsP3 following the flash that the Ca2+ signal is initiated in the extreme apical region of the cell-mimicking precisely the spatial dynamics of secretagogue stimulation. The change in [Ca2+]i measured in an apical region (red trace and box) and basal region (black trace and box) is shown in the top panel, illustrating the delay as the wave proceeds across the cell (Adapted from (Straub et al., 2000) with permission. In B, a cartoon illustrates the Ca2+ signaling machinery localized to the extreme apical pole. All InsP3R family members are localized immediately below the apical PM and at much higher density that elsewhere in the cell and are responsible for initiating the Ca2+ signal (Yule et al., 1997). SERCA and PMCA Ca2+ pumps are expressed in this region on apical ER and PM respectively (Lee et al., 1997a). Mitochondria surround the apical granule containing region and are responsible for limiting the spread of Ca2+ waves (Tinel et al., 1999; Straub et al., 2000).

These remarkable spatial and temporal characteristics are attributed to the dynamic interplay between the proteins responsible for Ca2+ release, influx and clearance from the cytoplasm (Figure 2B). While the general class, or in some cases, the gene family of the proteins responsible has been indicated, it is common that multiple individual members of gene families are expressed. With little discriminating conventional pharmacology available, the particular proteins which are responsible for a specific attribute of the Ca2+ signal has been difficult to establish. Additionally, whether expression of multiple protein family members represents redundancy or a means of permitting subtype specific regulation is not clearly established. Recently, studies utilizing transgenic gene targeting of particular signaling proteins have begun to address these gaps in our knowledge. In this review, selected studies will be highlighted which have provided insight into the particular proteins contributing to Ca2+ homeostasis in pancreatic acinar cells in both physiological and pathological conditions.

2. Cellular Origins

In mice at embryonic day 9.5, the pancreas begins to develop from buds that form as the endodermal gut tube envaginates into the overlying mesenchyme (Gittes, 2009). The bud elongates and undergoes extensive branching morphogenesis in response to complex signals to the epithelial cells from the surrounding mesenchyme and matrix. At around E14 cellular differentiation and lineage selection is initiated. A major amplification in the numbers of both endocrine cells expressing insulin and concurrent activation of acinar cell specific gene programs occurs. The latter event results in cells with substantial rough endoplasmic reticulum and zymogen granules. An increase in the zymogen content and the size of the granules in the acinar cells occurs until birth.

3. Functional significance of the expression of multiple InsP3R family members in acinar cells

All three members of the InsP3R gene family are expressed in acinar cells with largely the same sub-cellular distribution, albeit with differing relative abundances (Wojcikiewicz, 1995; Lee et al., 1997b; Yule et al., 1997). The majority, ~90% of the InsP3R complement comprises roughly equal numbers of InsP3R-2 and InsP3R-3 with the remainder InsP3R-1 (Wojcikiewicz, 1995). This raises the question as to whether this is reflective of redundancy or do particular sub-types make specific contribution to the signals? Transgenic knock-out of individual or a combination of InsP3R genes has provided significant insight into these issues. Futatsugi and colleagues (Futatsugi et al., 2005) reported that targeted ablation of either the type-2 or type-3 InsP3R individually, had no significant effects on muscarinic- receptor stimulated digestive enzyme secretion and these animals had no overt phenotype. Consistent with these observations, the peak secretatagogue-stimulated increases in [Ca2+]i were not altered (Futatsugi et al., 2005) by the removal of InsP3R-3 and only modestly impacted by the loss of the InsP3R-2 (Futatsugi et al., 2005; Park et al., 2008) In InsP3R-2 null acini, marked changes were only seen at low secretagogue or InsP3 concentrations (Park et al., 2008). In both cases the spatial aspects of the signals were largely unaffected. Taken together these data indicate that the complement of InsP3R-2 or InsP3R-3 in isolation, or perhaps in combination with InsP3R-1, is sufficient to maintain signaling and preservation of stimulated exocytosis.

Analysis of the compound InsP3R-2/InsP3R-3 null animal revealed a much more striking phenotype resulting from the widespread general disruption of exocrine function (Futatsugi et al., 2005). Although animals were born normally, they failed to survive past weaning, largely due to a failure to ingest and subsequently assimilate food. Even when fed wet mash food to overcome the salivary deficit, the animals failed to thrive as a result of diminished pancreatic secretory function. The immediate cause being, somewhat surprisingly, the complete absence of any measurable secretagogue-induced Ca2+ signal-even at supramaximal concentrations of agonist (Futatsugi et al., 2005). The conclusion from these data is that while the residual expression of InsP3R-1 is not sufficient to mount a Ca2+ signal, either the InsP3R-2 or InsP3R-3 in isolation will suffice.

InsP3R are subject to diverse regulatory input which is thought to markedly influence the properties of the Ca2+ signal (Patel et al., 1999). As a result of considerable diversity in the primary sequence of the family members, modulation often occurs in a subtype specific manner. Given the previous data, the important modes of regulation of Ca2+ release in acinar cells would be predicted to occur predominately through either modulation of InsP3R-2 and InsP3R-3. It is however difficult to predict if one particular receptor’s properties would dominate over the other. Ca2+ release via InsP3R is markedly influenced by the levels of cellular ATP, potentially linking the extent of Ca2+ release to the metabolic status of the cell. In acini, ATP (~Kd 40 µM) markedly enhances Ca2+ release at low levels of stimulation but appears not to influence release at high InsP3 levels (Park et al., 2008). In contrast in InsP3R-2 knock out animals, presumably dominated by InsP3R-3, ATP was shown to modulate release at all InsP3 levels, however the Kd for this effect was 10 fold higher (~450 µM). Interestingly, the properties of the wild–type animal are essentially identical to those shown for the InsP3R-2 in isolation, while the InsP3R-2 KO mirror those of the InsP3R-3 (Betzenhauser et al., 2008). These data indicate that while for Ca2+ release per se, InsP3R-2 and InsP3R-3 are interchangeable, in terms of the fine regulation of Ca2+ release, the individual InsP3R are not redundant. Further, when expressed together the properties of InsP3R-2 dominate over InsP3R-3. Moreover, the high ATP sensitivity of InsP3R-2 would be consistent with acinar cells being relatively resistant to the deleterious effects of ATP depletion.

4. The molecular basis of Ca2+ influx in pancreatic acinar cells

Secretagogue stimulated Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space is absolutely required for sustained exocytosis (Tsunoda et al., 1990). In acinar cells, like other exocrine cells, voltage-operated Ca2+ channels, common to nerves and muscles, are not expressed. Instead, following the InsP3-mediated depletion of Ca2+ pools, so called “store-operated channels” (SOCs) are activated (Kim et al., 2009). In addition, at lower concentrations of secretagogues, a pathway dependent on the arachidonic- acid activation of a Ca2+ selective channel is engaged (Mignen et al., 2005). In other cells, recent studies have indicated that the channels constituting the depletion-operated pathway are from either the Orai or TRPC family (Feske et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007). In both cases, an additional protein, STIM-1, functions as the luminal ER Ca2+ sensor responsible for relaying the state of store depletion to the actual channel protein (Roos et al., 2005). Pancreatic acinar cells express TRPC1, 3 and 6. Using a TRPC3 null animal, Kim and colleagues demonstrated that the magnitude of Ca2+ influx initiated by high-concentrations of agonist was significantly reduced. In addition, the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations stimulated by physiological concentrations of secretagogues was also markedly reduced. These data suggest that TRPC3 is a constituent of the native SOC in pancreatic acinar cells (Kim et al., 2009). Pancreas also express Orai 1 (Gwack et al., 2007) and this is consistent with the presence of an additional SOC, Calcium-Release Activated Current (ICRAC) and the Arachidonate-Activated Current (IARC) both of which have Orai-1 as a component of their native channel (Feske et al., 2006; Mignen et al., 2008).

5. Dysregulated Ca2+ signaling is associated with pancreatitis

To safeguard the organ from auto-digestion, digestive enzymes are largely secreted as inactive precursors termed zymogens and under physiological conditions only become activated when they reach the duodenum. The inappropriate activation of zymogens occurs as an early event in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis- a serious and often life threatening malady which can result in a wide-spread immune response and severe necrosis of the pancreas (Pandol et al., 2007). Disruption of physiological Ca2+ signaling and premature, intracellular activation of proteases has been strongly implicated in the etiology of acute experimental pancreatitis in animal models (Petersen & Sutton, 2006). Aberrant Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx have both been reported to contribute to this phenomenon. For example, exposure of isolated acini to pancreatic toxins such as bile acids or ethanol metabolites results in Ca2+ release from InsP3-sensitive stores (Gerasimenko et al., 2009). In turn, this results in intracellular trypsin activation and the cellular hallmarks of pancreatitis. It has been reported that this occurs at least in part through activation of InsP3R directly. Consistent with the dominant expression of InsP3R-2 and InsP3R-3, toxin-induced Ca2+ release and trypsin activation are markedly attenuated in either the InsP3R-2 or InsP3R-3 null animal, unaffected in the InsP3R-1 animal, and absent in the compound double knock-out (Gerasimenko et al., 2009). A question arises as to why Ca2+ release via InsP3R stimulated by toxins is detrimental to the acinar cell, while physiologically InsP3-induced release is essential for normal exocytosis? The answer may be related to the identity of the store as both bile acids and ethanol metabolites appear to activate insP3R in a compartment defined as an “acidic store” distinct from the ER (Gerasimenko et al., 2009). Prolonged Ca2+ entry through SOCs has also been demonstrated to contribute to experimental pancreatitis. Consistent with the role of TRPC-3 as a component of native SOC, the severity of experimental pancreatitis is markedly reduced in TRPC-3 null animals (Kim et al., 2009).

6. Concluding Remarks

Analysis of Ca2+ signaling in transgenic animal models has provided a wealth of information regarding stimulus-secretion coupling in pancreatic acini in both physiological and pathological situations. The availability of additional animal models, particularly pancreas-specific knock-downs of other signaling proteins will similarly be insightful in the future. Obvious potential targets for investigation include other Ca2+ release channels such as ryanodine receptors and Two-Pore Channels (TPC); Ca2+ influx channels including the Orai channels and clearance proteins such as Ca2+ ATPases and mitochondrial Ca2+ transport proteins.

Acknowledgements

The Author is supported by grants RO1-DK05458 and R01-DE014756 from the National Institutes of Health. The Author would like to thank Jill Thompson for thorough proof reading of the manuscript and Dr. Guy Groblewski and Diana Thomas for providing the electron micrograph in figure 1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Betzenhauser MJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Iwai M, Michikawa T, Mikoshiba K, Yule DI. ATP modulation of Ca2+ release by type-2 and type-3 inositol (1, 4, 5)-triphosphate receptors. Differing ATP sensitivities and molecular determinants of action. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21579–21587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801680200. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futatsugi A, Nakamura T, Yamada MK, Ebisui E, Nakamura K, Uchida K, Kitaguchi T, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Aruga J, Mikoshiba K. IP3 receptor types 2 and 3 mediate exocrine secretion underlying energy metabolism. Science. 2005;309:2232–2234. doi: 10.1126/science.1114110. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko JV, Lur G, Sherwood MW, Ebisui E, Tepikin AV, Mikoshiba K, Gerasimenko OV, Petersen OH. Pancreatic protease activation by alcohol metabolite depends on Ca2+ release via acid store IP3 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10758–10763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904818106. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes GK. Developmental biology of the pancreas: a comprehensive review. Developmental biology. 2009;326:4–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.024. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Feske S, Cruz-Guilloty F, Oh-hora M, Neems DS, Hogan PG, Rao A. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16232–16243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609630200. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H, Augustine GJ. Cytosolic Ca2+ gradients triggering unidirectional fluid secretion from exocrine pancreas. Nature. 1990;348:735–738. doi: 10.1038/348735a0. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H, Li YX, Miyashita Y. Subcellular distribution of Ca2+ release channels underlying Ca2+ waves and oscillations in exocrine pancreas. Cell. 1993;74:669–677. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90514-q. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Hong JH, Li Q, Shin DM, Abramowitz J, Birnbaumer L, Muallem S. Deletion of TRPC3 in mice reduces store-operated Ca2+ influx and the severity of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1509–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.042. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Xu X, Zeng W, Diaz J, Kuo TH, Wuytack F, Racymaekers L, Muallem S. Polarized expression of Ca2+ pumps in pancreatic and salivary gland cells. Role in initiation and propagation of [Ca2+]i waves. J Biol Chem. 1997a;272:15771–15776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15771. 1997a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Xu X, Zeng W, Diaz J, Wojcikiewicz RJ, Kuo TH, Wuytack F, Racymaekers L, Muallem S. Polarized expression of Ca2+ channels in pancreatic and salivary gland cells. Correlation with initiation and propagation of [Ca2+]i waves. J Biol Chem. 1997b;272:15765–15770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15765. 1997b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Cheng KT, Bandyopadhyay BC, Pani B, Dietrich A, Paria BC, Swaim WD, Beech D, Yildrim E, Singh BB, Birnbaumer L, Ambudkar IS. Attenuation of store-operated Ca2+ current impairs salivary gland fluid secretion in TRPC1(−/−) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17542–17547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701254104. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama Y, Inooka G, Li YX, Miyashita Y, Kasai H. Agonist-induced localized Ca2+ spikes directly triggering exocytotic secretion in exocrine pancreas. Embo J. 1993;12:3017–3022. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05970.x. 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Both Orai1 and Orai3 are essential components of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels. J Physiol. 2008;586:185–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146258. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O, Thompson JL, Yule DI, Shuttleworth TJ. Agonist activation of arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels in murine parotid and pancreatic acinar cells. J Physiol. 2005;564:791–801. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085704. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson MH, Fallon MB, Padfield PJ, Maranto AR. Localization of the type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in the Ca2+ wave trigger zone of pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4693–4696. 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandol SJ, Saluja AK, Imrie CW, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis: bench to the bedside. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1056 e1051–1056 e1025. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.055. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Betzenhauser MJ, Won JH, Chen J, Yule DI. The type 2 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor determines the sensitivity of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release to ATP in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26081–26088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804184200. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Joseph SK, Thomas AP. Molecular properties of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:247–264. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0021. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OH, Sutton R. Ca2+ signalling and pancreatitis: effects of alcohol, bile and coffee. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2006;27:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.12.006. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub SV, Giovannucci DR, Yule DI. Calcium wave propagation in pancreatic acinar cells: functional interaction of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors, ryanodine receptors, and mitochondria. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:547–560. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.4.547. 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streb H, Irvine RF, Berridge MJ, Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306:67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn P, Lawrie AM, Smith PM, Gallacher DV, Petersen OH. Local and global cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in exocrine cells evoked by agonists and inositol trisphosphate. Cell. 1993;74:661–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90513-p. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinel H, Cancela JM, Mogami H, Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH. Active mitochondria surrounding the pancreatic acinar granule region prevent spreading of inositol trisphosphate-evoked local cytosolic Ca(2+) signals. Embo J. 1999;18:4999–5008. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4999. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda Y, Stuenkel EL, Williams JA. Characterization of sustained [Ca2+]i increase in pancreatic acinar cells and its relation to amylase secretion. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G792–G801. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.5.G792. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Yule DI. Stimulus-secretion coupling in pancreatic acinar cells. In: Johnson ELR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1337–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikiewicz RJ. Type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11678–11683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11678. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule DI, Ernst SA, Ohnishi H, Wojcikiewicz RJ. Evidence that zymogen granules are not a physiologically relevant calcium pool. Defining the distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9093–9098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9093. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule DI, Gallacher DV. Oscillations of cytosolic calcium in single pancreatic acinar cells stimulated by acetylcholine. FEBS Lett. 1988;239:358–362. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80951-7. 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule DI, Lawrie AM, Gallacher DV. Acetylcholine and cholecystokinin induce different patterns of oscillating calcium signals in pancreatic acinar cells. Cell Calcium. 1991;12:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(91)90016-8. 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]