ABSTRACT

Background:

Therapy with drug-eluting microspheres was recently introduced with an aim to decrease the high postoperative morbidity associated with chemoembolization with lipiodol. The purpose of our study was to assess the safety and efficacy of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting microspheres (DEB-TACE) for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Material and Methods:

In this IRB-approved retrospective study, 54 patients (44 men; median age, 61 years) with inoperable HCC were treated with DEB-TACE. HCC was diagnosed by biopsy in 43 and with a combination of α-fetoprotein (AFP) and imaging in 11. Patients with Child-Pugh A, B, C cirrhosis were 27, 25, 2, respectively. Twenty-one patients had received local therapies prior to DEB-TACE. Tumor was multifocal in 30. Eight patients had branch portal vein thrombosis. DEB-TACE was performed using 300-500μ LC Beads™ mixed with 100 mg of doxorubicin. Twenty-two patients had one DEB-TACE procedure, 23 patients had 2, 8 patients had 3, and 1 had four procedures. Response rate (RR) was assessed using AFP, RECIST, and EASL criteria on CT/MRI at 1 and 3 months. Overall median survival and survival rates at 6, 12, and 24 months were calculated.

Results:

DEB-TACE was technically successful in all. Mean hospital stay after the procedure was 1.59 days. Thirty-day mortality was 0%. RR based on AFP was 26%. At 1 and 3 months, CR + PR were 14.8% and 35%, SD 74.1% and 50%, and PD 11.1% and 15%. Overall median survival was 445 days (95% CI 312–590). The survival rates at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were 77%, 59%, and 32% respectively.

Conclusions:

Chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting microspheres is safe and well tolerated in patients with inoperable HCC. Its efficacy is comparable to the historical controls. However, further prospective studies are required to confirm its efficacy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of cancer-related death.1 It is more common in Asia and Africa, but its incidence in the United States has nearly doubled in the past decade, largely due to underlying hepatitis C (HCV) infection.2 Treatment options for HCC are broadly categorized into surgical—consisting of resection and transplantation—and nonsurgical—consisting of systemic chemotherapy and regional therapies such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and microwave ablation. Surgical resection and liver transplantation are curative;3,4 however, the majority of patients are not eligible for surgical treatment, either because of the advanced stage of the tumor, liver dysfunction, or lack of donors.5

HCC is resistant to chemotherapy.6,7 Consequently, regional therapies play a significant role in the management of patients who otherwise cannot undergo surgical resection or transplantation. TACE has been the mainstay of treatment for patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) intermediate-stage disease.8,9 Conventional method of delivering TACE involves the use of lipiodol, chemotherapy drugs (such as doxorubicin, mitomycin, cisplatin) and embolization of the parent vessel with gel-foam or particles.10

TACE results in high intratumoral concentration of chemotherapy drugs and ischemic injury of tumor cells due to the fact that the chemotherapy agents are delivered directly into the hepatic artery and the arterial flow is temporarily decreased through embolization of the parent vessel.11,12 Lipiodol helps to block the portal venous outflow by blocking the portal vein branches, thus increasing the contact time between chemotherapy drugs and tumor cells.13 However, recent data suggest that the systemic release of chemotherapy agents following conventional TACE is high,14,15 and many patients suffer from systemic side effects.16 Lipiodol infusion interferes with interpretation of subsequent computed tomography (CT) imaging for detection of tumor recurrence.

These factors led to further research for developing a different method of local drug delivery while still keeping the advantages of traditional TACE. One of these methods is the use of drug-eluting microspheres for TACE (henceforth referred to as “DEB-TACE” in this article). The current generations of drug-eluting microspheres are loaded with doxorubicin.17 The loading and eluting kinetics of doxorubicin-eluting microspheres are well described in the literature.15 DEB-TACE ensures slow and sustained release of the drug locally in addition to causing ischemic injury to the tumor.16

It is expected that DEB-TACE decreases the systemic toxicity traditionally associated with conventional TACE, and the procedure might be better tolerated. In vitro data confirmed the slow sustained release of the drug.15 However, few clinical studies have assessed the clinical safety and efficacy of this procedure for treatment of inoperable HCC. The purpose of our study is to evaluate the clinical safety and efficacy of DEB-TACE for the treatment of inoperable HCC.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Our institution's Human Research Committee approved this study and the requirement to obtain informed consent for this retrospective study was waived. The study was HIPAA compliant.

Patients

Included in this analysis are data from 54 consecutive patients who were treated with DEB-TACE at our institution from November 2005 to June 2009. Inclusion criteria were presence of inoperable HCC and absence of main portal vein thrombosis. Exclusion criteria were poor functional status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group[ECOG] score >2), presence of moderate ascites, bilirubin >2mg/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) >2, serum creatinine >2mg/dL and presence of extensive extrahepatic disease. HCC was diagnosed histologically (43/54, 79.6%) or by means of a combination of imaging characteristics and elevated serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) (11/54, 20.4%).18 Forty patients (74%) had cirrhosis. The etiology of cirrhosis was viral infection with hepatitis C (HCV) or B (HBV) in 30 patients (HCV in 22, HBV in 4, a combination of HBV and HCV in 4), cryptogenic in 3, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in 1. Eighteen of 30 patients with viral cirrhosis also had a history of alcohol abuse.

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics and laboratory data at the time of DEB-TACE procedure are listed in Table 1. Median age of the patients at first TACE was 62 years (range, 43–81 years). In 22 patients (40.7%), the tumor measured greater than 5 cm in its largest dimension on cross-sectional imaging CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In the remaining 32 patients (59.4%), the tumor measured 5 cm or less. The tumor was confined to the right lobe in 23 patients (42.6%) and to the left lobe in 5 (9.3%). Bilobar tumor was present in 26 (48.1%). Multifocal disease was seen in 31 patients (57.4 %). At presentation, 12 patients (22.2%) had pulmonary metastases. Eight (14.8%) had branch portal vein thrombosis. Abnormal liver function tests were seen as elevated total bilirubin in 32 patients (59.3 %), AST in 45 (83.3 %), ALT in 30 (55.5 %), low albumin in 17 patients (31.5%) and alkaline phosphatase in 39 (72.3%) (Table 1). AFP was elevated in all patients.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| N (%) | ||

| Patient demographics | ||

| Age (years) | ≤65 | 20 (37.0) |

| >65 | 34 (63.0) | |

| Median | 57 | |

| Gender | Female | 44 (81.5) |

| Male | 10 (18.5) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 38 (70.4) |

| Asian | 9 (16.7) | |

| Black | 5 (9.2) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (3.7) | |

| Child-Pugh grade | A | 27 (50.) |

| B | 25 (46.3) | |

| C | 2 (3.7) | |

| Previous treatment | Yes | 21 (38.9) |

| No | 33 (61.1) | |

| Tumor characteristics | ||

| Mean tumor size | ≤5cm | 22 (40.7) |

| >5cm | 32 (59.3) | |

| Tumor distribution | Multifocal | 31 (57.4) |

| Unifocal | 23 (42.6) | |

| Hepatic lobe | Right | 23 (42.6) |

| Left | 5 (9.3) | |

| Both | 26 (48.1) | |

| Branch portal vein thrombosis | Yes | 8 (14.8) |

| No | 46 (85.2) | |

| Extra hepatic (pulm) metastases | Yes | 8 (14.8) |

| No | 46 (85.2) | |

| Lab data | ||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | ≤1.0 | 32 (59.3) |

| >1.0 | 22 (40.7) | |

| AST (IU/L) | ≤40 | 9 (16.7) |

| >40 | 45 (83.3) | |

| ALT (IU/L) | ≤55 | 24 (44.5) |

| >55 | 30 (55.5) | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | ≤115 | 15 (27.7) |

| >115 | 39 (72.3) | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | >3.2 | 37 (68.5) |

| ≤3.2 | 17 (31.5) | |

| INR | ≤1.5 | 52 (96.3) |

| >1.5 | 2 (3.7) | |

| AFP (IU) | <100 | 29 (53.7) |

| 100–1000 | 10 (18.5) | |

| >1000 | 15 (27.8) | |

Patients were referred to DEB-TACE procedure after a median period of 164 days (mean, 282 days; range, 22 to 1985 days) from the time of HCC diagnosis. Twenty-one patients (38.9%) had received various forms of therapy prior to DEB-TACE. These included RFA in 10 patients, surgical resection in 4, surgical resection and RFA in 1, surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy in 1, conventional TACE in 2, conventional TACE and RFA in 1, and conventional TACE and systemic chemotherapy in 2.

Preprocedure evaluation included review of medical history, physical examination, and laboratory studies for hematologic, hepatic, and renal functions along with serum AFP. The imaging workup consisted of a baseline contrast-material enhanced CT or MRI within 1 month preceding the DEB-TACE procedure. Following the procedure, patients were followed at 4–8 weeks interval through clinical, laboratory, and imaging evaluation.

DEB-TACE Procedure

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. All procedures were performed according to a standard protocol. Patients were kept nil per oral (NPO) status for at least 8 hours prior to the procedure. All patients were premedicated with antibiotics (cefazolin) and antacids (ranitidine). Drug-eluting microspheres were prepared using 300μ–500μ LC Beads™ (AngioDynamics, Queensbury, NY). A total of 4 mL of microspheres were mixed with 100 mg of doxorubicin according the manufacturer's guidelines.

Fifty three patients received conscious sedation during the procedure using fentanyl and midazolam. Blood pressure, oxygen saturation, electrocardiographic parameters, and heart rate were monitored during the entire procedure. One patient received general anesthesia. Right femoral arterial access was used in all patients. Celiac and/or superior mesenteric arteriography was performed to assess the arterial anatomy, vascular supply to the tumor, and patency of the portal vein. The lobar/segmental hepatic artery supplying the tumor was selectively cannulated with a microcatheter and embolized with drug-eluting microspheres, which were mixed with nonionic iodinated contrast material in a ratio of 1:1.

The end point for embolization was stasis of blood flow in the arterial feeders to the tumor. A search with additional angiography was made for detection of extrahepatic arterial supply to the tumor. If the extrahepatic artery was suitable for embolization, the artery was selectively cannulated and embolized with drug-eluting microspheres. Patients were admitted for observation for 24 hours following the procedure. Prophylactic medications against nausea (ondansetron IV), pain (hydromorphone PCA) and infection (ciprofloxacin and metronidazole) along with intravascular hydration were administered during hospitalization.

Data Analysis

All patients were followed at 4–8 week intervals up to July 2009 or until their death or liver transplantation. Primary outcome was survival; secondary outcomes were complications, length of hospital stay, readmission rates, posttreatment change in AFP value, biochemical changes, and objective tumor response on imaging using RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) and EASL (European Association for the Study of the Liver) criteria.19,20

Kaplan-Meier graphs were obtained for survival proportions for all patients, patients in Child-Pugh A group, and patients in Child-Pugh B group. From these graphs, overall median survival and survival rates at 6, 12, and 24 months were estimated for all patients and for patients in Child-Pugh A and B groups. Median survival was also calculated based on baseline serum bilirubin, albumin, and INR data by grouping all patients into two categories (Table 2). Response to therapy was assessed on imaging at 1, 3, and 6 months using RECIST criteria19 and modified EASL criteria.20 Response based on decrease in serum AFP of 50% or more from baseline was also calculated.21

Table 2.

Post DEB-TACE survival rates at 6-, 12-, and 24-month time points with respect to Child-Pugh score and laboratory values*

| Measure | Level | Survival rates |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 24 months | ||

| Child-Pugh score | A | 21/23 (91.3%) | 10/23 (43.4%) | 4/23 (17.4%) |

| B | 15/19 (78.9%) | 6/19 (31.6%) | 3/19 (15.8%) | |

| C | 0/2 (0%) | |||

| Bilirubin level | ≤1.0 | 22/27 (81.5%) | 9/27 (33.3%) | 4/27 (14.8%) |

| ≥1.0 | 14/17 (82.4%) | 7/17 (41.2%) | 3/17 (17.6%) | |

| Albumin | ≥3.2 | 24/29 (82.7%) | 10/29 (34.5%) | 4/29 (13.8%) |

| <3.2 | 12/15 (80%) | 6/15 (40%) | 3/15 (20%) | |

| INR | ≤1.6 | 35/42 (83.3%) | 15/42 (35.7%) | 6/42 (14.3%) |

| ≥1.6 | 1/2 (50%) | 1/2 (50%) | 1/2 (50%) | |

Data for 44 patients only. Ten patients had been excluded from this chart as they had DEB-TACE procedure within recent 6 months.

Safety of DEB-TACE was assessed by calculating incidence of postprocedure complications according to Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) guidelines. The incidence of post-procedure liver failure, renal failure or death within 30 days of the procedure was also calculated. Biochemical toxicity was assessed using National Cancer Institute – Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 3.0.22

RESULTS

Procedure and Complications

DEB-TACE was technically successful in all patients. A total of 96 DEB-TACE procedures were performed in 54 patients during the 4-year period. Twenty-three patients (42.6%) had two treatments, 8 patients (14.8%) had three treatments and 1 (1.9%) had four treatments. The remaining 22 patients (40.7%) had one session of DEB-TACE. The average number of procedures was 1.77 ± 0.82. Mean hospital stay after the procedure was 1.59 days (range 1–8 days).

Pain, nausea, and fatigue were the most common side effects following DEB-TACE, with a frequency of 42.6%, 14.8%, and 35.2% at 7 days and 5.6%, 0%, and 14.8% at 28 days, respectively (Table 3). At 7 days following all 94 procedures, three patients had major complications (abscess in 2 and intratumoral bleed in 1). Thirty-day procedural mortality was zero (0%). Within 30 days of the procedure, no patient developed liver failure; 6 patients developed mild renal insufficiency that subsequently improved.

Table 3.

Complications post DEB-TACE (96 procedures) at follow up

| Type | 7 days | 14 days | 28 days |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 23 | 6 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 19 | 7 | 8 |

| Nausea & vomiting | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Shortness of breath | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Fever | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Groin hematoma | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Abscess | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Intratumor bleed | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver failure | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal insufficiency | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 |

At 24 hours post-DEB-TACE, total bilirubin remained unchanged, whereas AST, ALT, and alkaline phosphatase showed significant increase. The values were classified according to the NCI-CTC version 3.0. At 1 month post DEB-TACE, nine patients had normal liver function tests, 39 patients were in grade 1, six patients in grade 2, and five patients in grade 3 of NCI v3 toxicity grading criteria.

Tumor Response

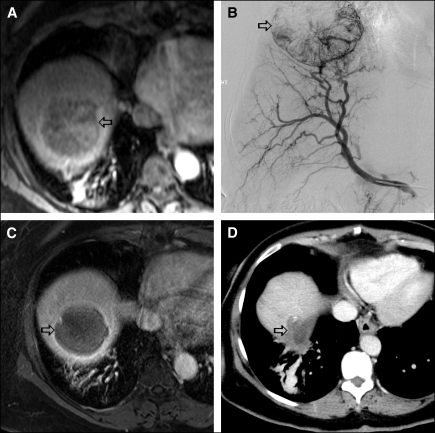

Based on RECIST criteria, 1-month response rate (RR), which included complete response (CR) plus partial response (PR), was 21%, stable disease (SD) 68%, and progression of disease (PD) 11%. At 3 months, RR was 27%, SD 55%, and PD 18%. At 6 months RR was 24.6%, SD was 50%, and PD was 25.4%. Two patients underwent liver transplantation 4.5 and 5.5 months after their last DEB-TACE session. Based on EASL criteria, 37 patients (68%) showed necrosis at 1 month (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

59-year-old woman with cirrhosis and HCC. MRI scan prior to DEB-TACE (1A) shows an enhancing lesion (arrow) in the right lobe of the liver. Right hepatic angiography (1B) shows enhancing mass lesion. One month following DEB-TACE, MRI scan (1C) shows necrosis of the tumor with no residual enhancement. Eighteen months following DEB-TACE, CT scan (1D) shows decrease in the size of the tumor with no local recurrence.

Response based on AFP was defined as a decrease of ≥50% of baseline AFP value.21 Fourteen patients (26%) showed response.

Survival

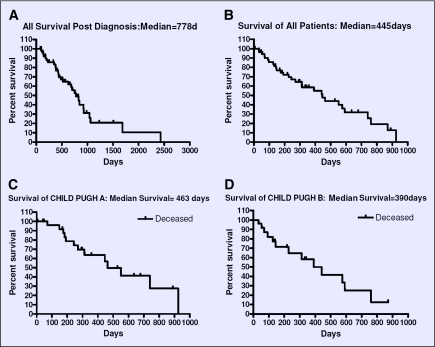

At the time of this analysis, 26 patients were alive and 28 had died of their disease. Actuarial survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Median follow-up was 244 days (range 7–924 days).

Postdiagnosis survival ranged from 81 days to 2,430 days, with a median of 778 days (26 months). Postdiagnosis median survival for Child Pugh A and Child Pugh B patients was 929 days (31 months) and 483 days (16 months), respectively.

Median overall survival following DEB-TACE for all patients was 445 days (14.8 months). Overall median survival following DEB-TACE for ECOG scores 0,1, and 2 was 454, 227, and 148 days, respectively. Median overall survival in days following DEB-TACE according to patient race was 256, 358, 169, and 548 for whites, Asians, blacks, and Hispanics, respectively. The median overall survival following DEB-TACE according to Child-Pugh A, B, and C groups was 463, 390, and 65 days, respectively. For all patients, post TACE survival at 6, 12, and 24 months was 77%, 59%, and 32% respectively. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for all patients post diagnosis, post DEB-TACE, and for patients in Child-Pugh A and Child-Pugh B groups following DEB-TACE.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Graphs: 2A: Survival post-diagnosis, all patients; 2B: Survival following DEB-TACE, all patients; 2C: Survival following DEB-TACE, Child-Pugh A patients; 2D: Survival following DEB-TACE, Child-Pugh B Patients.

DISCUSSION

HCC is one of the most common tumors and is a leading cause of mortality. Even with the advent of screening for HCC in high-risk patients, most patients are diagnosed at an advanced disease stage.23 Surgery offers the only hope of cure; however, less than 20% of patients diagnosed with HCC are eligible for surgery. The prognosis of unresectable HCC is very poor. Systemic chemotherapy has long been unavailable, and the patients are particularly vulnerable to treatment-related adverse effects.6,7

Conventional TACE has been shown to improve survival of patients with unresectable HCC.24,25 Though early studies showed equivocal results in terms of survival benefits,26,27 later randomized studies showed a survival advantage with TACE in comparison to symptomatic therapy.28–31 Chemotherapy agents administered through TACE escape first-pass metabolism, have a prolonged half-life, and achieve high intratumoral average drug concentration allowing more dose intense delivery of the chemotherapeutic agent. However, a few studies have shown significant passage of the chemotherapeutic agent to systemic circulation with no difference in the peak concentration and area under the time vs. concentration curve (AUC) between TACE and systemic therapy.32 Drug-eluting microspheres provide a new strategy to achieve high intratumoral drug concentration in addition to ischemic effects, those commonly seen with conventional TACE.

Recent studies have shown that doxorubicin-eluting microspheres when administered intra-arterially as a modified technique of TACE have an acceptable safety profile.17,33,34 Our results also support favorable safety profiles of DEB-TACE. Thirty-day mortality in our study was 0% and no patient had liver failure following the procedure. This is comparable to other studies reported in the literature.17,28,33–35 Acute renal failure occurred in 6 patients (of 94 procedures), which subsequently improved with medical management. Two major complications, abscesses, were managed with medical therapy and catheter drainage. Among others, fatigue was the most common complication, occurring at a frequency of 14.8% at 28 days post procedure.

In our study, patients with inoperable HCC who were treated with DEB-TACE had 77%, 59%, and 32% survival at 6, 12, and 24 months respectively. Overall median survival was 445 days. The median survival was higher in Child-Pugh A group (463 days) and in patients with ECOG 0 performance status (454 days). Reported survival following TACE for unresectable HCC differed substantially from studies across the world. One study from Asia reported a survival of 57% and 31% at 1 and 2 years follow-up respectively.30 Another from Europe reported a survival of 82% and 63% at 1 and 2 years respectively.28 One North American study reported a survival of 76% and 56% at 1 and 2 years respectively.31 This large discrepancy of survival among different studies can be explained by patient selection bias, underlying etiology of cirrhosis, prior treatments, and other comorbidities.

The survival rates in our study at 1 year and 2 years was 59% and 32%, respectively, which is comparable to those reported in previous studies.30,36 In our study population, patients were referred for DEB-TACE procedure after a significant delay from the time of HCC diagnosis. The time delay from the diagnosis to the first DEB-TACE ranged from 22 to 1985 days, with a median delay of 164 days. In addition, half of our patients were referred to DEB-TACE following failure of other locoregional therapies, which suggests the presence of a biologically aggressive cancer at the time of DEB-TACE. Around 40% of our patients had a single DEB-TACE session, which limits the effectiveness of this therapy compared to repeated chemoembolization.37

Other reasons for low survival in our study might be attributable to old age at the time of presentation, Child-Pugh status at the time of therapy, low dose of doxorubicin (100 mg per session) and presence of branch portal vein thrombosis and extrahepatic disease. Overall survival from time of HCC diagnosis ranged from 81 days to 2,430 days, with a median of 778 days, which is similar to previously published reports.

Tumor response rate using RECIST criteria was of 24.6% and 69.7% at 6 months and 12 months, respectively. However, stable disease was found in 50% and 30% at 6 and 12 months respectively. By the EASL necrosis criteria, 68.5% patients showed response at one month, which is comparable to other studies.38

There are limitations in our study. First, this is a retrospective study. Though a prospective study is ideal, our study provided follow-up, response rates, and survival data. Second, the study population is small. Third, patients were not randomized to conventional TACE and DEB-TACE to assess the superiority of one over the other. Fourth, patients were referred to DEB-TACE procedure after a median period of 164 days from the time of diagnosis. Earlier intervention might have led to better survival.

Recently, sorafenib, an orally available multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), demonstrated a statistically and clinically significant improvement in median overall survival in two randomized phase III trials in advanced HCC patients, and has been widely approved worldwide.39,40 Whether this agent can be combined with conventional TACE or DEB-TACE to improve the treatment outcome of HCC patients further is an area of active clinical investigation.

In summary, we conclude that transarterial chemoembolization using doxorubicin-eluting microspheres is safe. Efficacy in our study was not as good as the historical controls. Thus, additional prospective studies are required to assess this measure further.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Kalva and Dr. Wicky have received unrestricted educational grants from Angiodynamics Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. : Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55:74–108, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. El-Serag HB: Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res 37 Suppl 2: S88–94, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olthoff KM: Surgical options for hepatocellular carcinoma: resection and transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg 4(5 suppl 1):S98–S104, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verslype C, Van Cutsem E, Dicato M, et al. : The management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current expert opinion and recommendations derived from the 10th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer, Barcelona, 2008. Ann Oncol 20(suppl 7)vii1–vii6, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dawwas MF, Gimson AE: Candidate selection and organ allocation in liver transplantation. Semin Liver Dis 29:40–52, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kerr SH, Kerr DJ: Novel treatments for hepatocellular cancer. Cancer Lett 286:114–120, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wörns MA, Weinmann A, Schuchmann M, et al. : Systemic therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis 27:175–188, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J: Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 19:329–338, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang JH, Changchien CS, Hu TH, et al. : The efficacy of treatment schedules according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging for hepatocellular carcinoma -Survival analysis of 3892 patients. Eur J Cancer 44:1000–1006, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ono Y, Yoshimasu T, Ashikaga R, et al. : Long-term results of lipiodol-transcatheter arterial embolization with cisplatin or doxorubicin for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 23:564–568, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soulen MC: Chemoembolization of hepatic malignancies. Oncology (Williston Park) 8:77–84; discussion 84, 89–90, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raoul JL, Heresbach D, Bretagne JF, et al. : Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinomas. A study of the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin. Cancer 70:585–90, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonneman B: Lipiodol—mechanism of action for chemoembolization. Jpn IVR 21:64–68, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson PJ, Kalayci C, Dobbs N, et al. : Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of intraarterial Adriamycin for hepatocellular carcinoma: effect of coadministration of lipiodol.J Hepatol 13:120–127, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis AL, Gonzalez MV, Lloyd AW, et al. : DC bead: in vitro characterization of a drug-delivery device for transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 17:335–342, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simonetti RG, Liberati A, Angiolini C, et al. : Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Oncol 8:117–136, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varela M, Real MI, Burrel M, et al. : Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: efficacy and doxorubicin pharmacokinetics. J Hepatol 46:474–481, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bruix J, Hessheimer AJ, Forner A, et al. : New aspects of diagnosis and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 25:3848–3856, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. : New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, et al. : Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol 35:421–430, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roayaie S, Frischer JS, Emre SH, et al. : Long-term results with multimodal adjuvant therapy and liver transplantation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomas larger than 5 centimeters. Ann Surg 235:533–539, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0, DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS 2003 (http://ctep.cancer.gov), Publish Date: August 9, 2006 Available at: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf

- 23. Okada S: Transcatheter arterial embolization for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the controversy continues. Hepatology 27:1743–1744, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 35:1164–1171, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. : Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359:1734–1739, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A comparison of lipiodol chemoembolization and conservative treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Groupe d'Etude et de Traitement du Carcinome Hépatocellulaire. N Engl J Med 332:1256–1261, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pelletier G, Ducreux M, Gay F, et al. : Treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with lipiodol chemoembolization: a multicenter randomized trial. Groupe CHC. J Hepatol 29:129–134, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. : Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359:1734–1739, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cammà C, Schepis F, Orlando A, et al. : Transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology 224:47–54, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 35:1164–1171, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Molinari M, Kachura JR, Dixon E, et al. : Transarterial chemoembolisation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from a North American cancer centre. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 18:684–692, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kalayci C, Johnson PJ, Raby N, et al. : Intraarterial Adriamycin and lipiodol for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison with intravenous Adriamycin. J Hepatol 11:349–353, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Poon RT, Tso WK, Pang RW, et al. : A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:1100–1108, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malagari K, Chatzimichael K, Alexopoulou E, et al. : Transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: results of an open-label study of 62 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 31:26–80, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Georgiades CS, Hong K, D'Angelo M, et al. : Safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 16:1653–1659, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. : Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30:6–25, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoshioka H, Sato M, Sonomura T, et al. : Factors associated with survival exceeding 5 years after transcatheter arterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol 24(2 suppl 6):S6-29-376–S6, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Malagari K, Alexopoulou E, Chatzimichail K, et al. : Transcatheter chemoembolization in the treatment of HCC in patients not eligible for curative treatments: midterm results of doxorubicin-loaded DC bead. Abdom Imaging 33:512–519, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. : Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359:378–390, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng AL, Kang Y-K, Chen Z, et al. : Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 10:25–34, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]