Abstract

Purpose

The role of RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) in antiviral defence mechanisms and in cellular differentiation, growth, and apoptosis is well known, but the role of PKR in human lung cancer remains poorly understood. To explore the role of PKR in human lung cancer, we evaluated PKR’s expression in tissue microarray specimens from both non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and normal human bronchial epithelium tissue.

Experimental Design

Tissue microarray samples (TMA-1) from 231 lung cancers were stained with PKR antibody and validated on TMA-2 from 224 lung cancers. Immunohistochemical expression score was quantified by three pathologists independently. Survival probability was computed by the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

The NSCLC cells showed lower levels of PKR expression than normal bronchial epithelium cells did. We also found a significant association between lower levels of PKR expression and lymph node metastasis. We found that loss of PKR expression is correlated with a more aggressive behavior, and that a high PKR expression predicts a subgroup of patients with a favorable outcome. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models showed that a lower level of PKR expression was significantly associated with shorter survival in NSCLC patients. We further validated and confirmed that PKR to be a powerful prognostic factor in TMA-2 lung cancer (HR=0.22, P<0.0001).

Conclusions

Our findings first indicate that PKR expression is an independent prognostic variable in NSCLC patients.

Keywords: PKR, Biomarker, Lung cancer

Introduction

RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) has a well-established role in antiviral defense mechanisms and other cellular functions, such as the regulation of growth, apoptosis, proliferation, signal transduction, and differentiation (1–5).

The role of PKR apparently varies with the type of human cancer. For example, Terada et al. reported significant correlations between high PKR scores and vascular invasion and the presence of satellite tumor nodules in thyroid carcinoma cases (6). Immunohistochemical analysis found minimal PKR immunoreactivity in primary tumors but high levels of PKR protein expression in lymph node metastases in melanoma cases (7). In a small study, Roh et al. found that patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) and high PKR expression levels had significantly shorter survival durations than did patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and low PKR expression levels (8).

Conversely, studies have shown that increased expression of PKR correlates with a better prognosis in patients with head and neck or colon cancer (9, 10). In addition, a positive correlation between PKR expression and the degree of differentiation among cancers of the colon, breast, liver, and head and neck has been shown (11–16). Researchers have suggested that PKR has a role as a tumor suppressor in patients with leukemia and other hematologic malignancies (17–19).

In recent years, we have studied PKR pathways and have found them to be clearly necessary for induction of cell death in some cancer cells including lung cancer after certain treatments (20–25). In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that differences in the levels of expression of PKR proteins could act as a prognostic marker for clinical outcomes in NSCLC patients. Our findings first indicate that PKR expression is an independent prognostic variable in NSCLC patients.

Materials and Methods

Tissue microarray (TMA) samples

Non-small cell lung cancer and normal human bronchial epithelium TMA specimens from the Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence Tissue Bank at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) (26). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Tumor tissue specimens for TMA-1 (Study set) and TMA-2 (Validation set) from 455 lung cancers (278 adenocarcinomas, and 177 squamous cell carcinomas) were histologically examined, classified using the WHO classification system (27), and selected for tissue microarray construction. After histologic examination, the tissue microarrays were constructed using triplicate 1 mm diameter cores from each tumor. Detailed clinical and pathologic information, including demographic data, smoking history (never- and ever-smokers), pathologic tumor-node-metastasis staging, overall survival, and time of recurrence, was available in most cases (Table 2 and Table 4).

Table 2.

Relationships between the level of PKR expression and clinicopathologic characteristics in 231 TMA-1 non-small cell lung cancer patients

| Characteristics | Total Number (%) (N=231) |

PKR expression Score | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<176) (N=116) |

High (>=176) (N=115) |

|||

| Gender | 0.05 | |||

| Male | 105 (45.5) | 56 (48.3) | 45 (39.1) | |

| Female | 126 (54.5) | 60 (51.7) | 70 (60.9) | |

| Pathological TNM stage | 0.02a | |||

| Stage I | 147 (63.6) | 65 (56.0) | 82 (71.3) | |

| Stag II | 48 (20.8) | 32 (27.6) | 16 (13.9) | |

| Stage III–IV | 36 (15.6) | 19 (16.4) | 17 (14.8) | |

| pT | 0.012b | |||

| T1 | 79 (34.2) | 31 (26.7) | 48 (41.7) | |

| T2 | 131 (56.7) | 73 (62.9) | 58 (50.4) | |

| T3 | 12 (5.2) | 7 (6.0) | 5 (4.3) | |

| T4 | 9 (3.9) | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.5) | |

| pN | 0.005c | |||

| N0 | 162 (70.1) | 71 (61.2) | 91 (79.1) | |

| N1 | 45 (19.5) | 32 (27.6) | 13 (11.3) | |

| N2 | 24 (10.4) | 13 (11.2) | 11 (9.6) | |

| pM | 0.11 | |||

| M0 | 225 (97.4) | 115 (99.1) | 110 (95.7) | |

| M1 | 6 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 5 (4.3) | |

| Histologic type | 0.001 | |||

| ACC | 132 (57.1) | 53 (45.7) | 79 (68.7) | |

| SCC | 99 (42.9) | 63 (54.3) | 36 (31.3) | |

| Tobacco history | 0.73 | |||

| No | 60 (26.0) | 29 (25.0) | 31 (27.0) | |

| Yes | 171 (74.0) | 87 (75.0) | 84 (73.0) | |

The p-value was calculated between pathologic stage I and II–IV.

Between T1 and T2–T4.

Between N0 and N1–N2.

SCC, squamous cell carcinoma. ACC, Adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemical staining and evaluation

The rabbit anti-PKR polyclonal antibody (K-17, SC-707) used for immunohistochemical staining was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Immunohistochemical staining performed as previously described (26).

Immunohistochemical expression was quantified by two pathologists independently for TMA-1 and TMA-2 (Drs. Raso and Pataer) using a 4-value intensity score (0 for negative, 1 for weak, 2 for moderate, or 3 for strong) and the percentage of tumor cells within each category was estimated. A final score was obtained by multiplying both intensity and extension values (0 × % negative tumor cells + 1 × % weakly stained tumor cells + 2 × % moderately stained tumor cells + 3 × % strongly stained tumor cells). The score ranged from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 300. Cases with discordant scores between observers were reevaluated.

Immunoblot and Flow cytometric analysis

Human lung (A549, H1299 and H322B), cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Poly IC was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). We measured apoptotic cells by propidium iodide staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (FL-3 channel, FACScan; Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) (20).

At 48 hrs after transfection, the cell extracts were prepared and immunoblot assays performed as previously described (20). Antibodies to PKR (K-17), phosphorylated PKR (Thr451), and β-actin (control) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Statistical analysis

Survival probability as a function of time was computed by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare patient survival time between groups. Cox regression was used to model the influence of PKR expression on survival time, with adjustment for clinical and histopathological parameters (age, sex, tumor histology subgroup, and smoking status). The 2-sided test was used to test proportions between groups in 2-way contingency tables. In univariate analysis, independent sample Student’s t and χ2 tests were used to analyze continuous and categorical variables, respectively. All of the statistical tests were 2-sided; P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were done using the S-Plus and the SPSS softwares.

Results

PKR expression in normal bronchial epithelium and NSCLC tumors

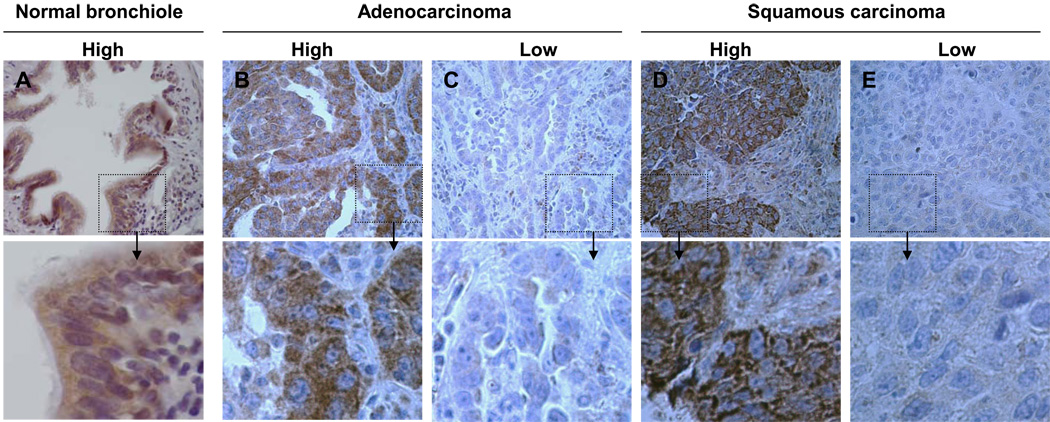

We investigated PKR expression in NSCLC by immunohistochemical analysis using TMAs from 88 normal bronchial epithelium samples and 231 NSCLC tumor samples (TMA-1) obtained from patients with stage I–IV disease who had not received neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy and for whom clinical outcomes were known. The samples consisted of 132 adenocarcinoma (ACC) and 99 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) samples. We detected PKR expression in both the cytoplasm and nuclei of bronchial epithelial cells but only in the cytoplasm of NSCLC cells (Fig. 1). Overall, we detected high-level PKR expression (mean score, 282) in normal bronchial epithelium samples and reduced PKR expression (mean score, 170) in NSCLC tumor samples (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1; Table 1). Clearly, NSCLC tumors showed reduced mean levels of PKR protein expression.

Fig. 1.

Representative results of immunohistochemical staining of normal human bronchial epithelium and NSCLC tumor specimens for PKR. (A, B, and D) Samples expressing high levels of PKR. (C and E) Samples expressing low levels of PKR. A shows nuclear and cytosolic localization of PKR in normal human bronchial epithelial tissue, whereas B–E show cytosolic localization of PKR in ACC and SCC tissue. Original magnification, ×40 (pictures) and ×400 (insets).

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of PKR expression in normal bronchial epithelium and lung cancer using TMA specimens

| Histology of samples | No. of samples |

PKR score mean (SD) |

PKR expression score | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<176) n (%) |

High (>=176) n (%) |

||||

| Normal epithelium | 88 | 282 (19) | 0 (0) | 88 (100) | Ref* |

| Cancer speciments | |||||

| ACC | 132 | 185 (70) | 53 (40.1) | 79 (59.9) | <0.001 |

| SCC | 99 | 155 (66) | 63 (63.6) | 36 (36.4) | <0.001 |

TMA, Tissue microarray. ACC, Adenocarcinoma. SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

The p-value was calculated between normal epithelium and ACC or SCC.

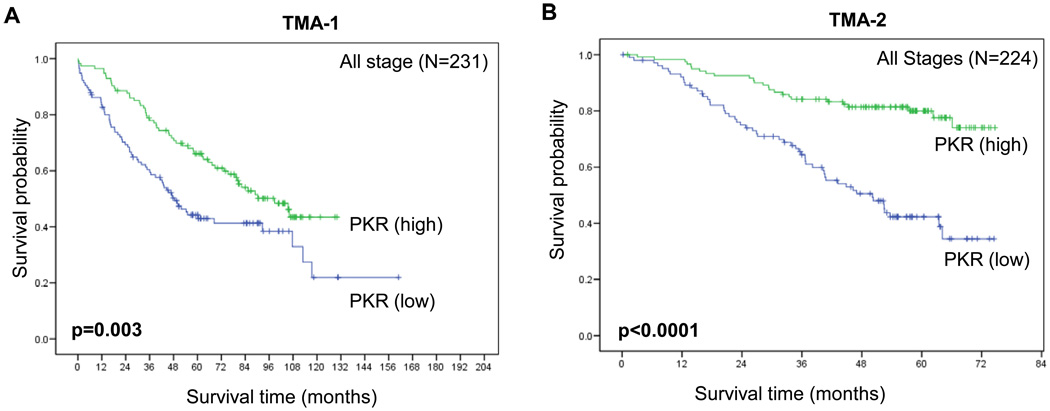

Correlation between PKR expression in NSCLC tumors and clinicopathologic features and disease outcomes

Using mean PKR expression scores, we did not detect any statistically significant correlations between protein expression and patient’s sex, smoking history, or pathologic tumor category (Table 2). Low-level PKR expression was correlated with stage II–IV versus stage I disease (P = 0.025), the presence of lymph node metastasis (P = 0.005), and SCC versus ACC (P = 0.001) (Table 2). We next analyzed the relationship between PKR expression and survival duration in pathologic all stage NSCLCs on TMA-1 (A). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 2 (A) show that low-level PKR expression was related to a significantly reduced probability of survival in the subgroup of patients in all stage patients (A) (P = 0.003). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that expression of PKR was significantly associated with the overall survival after accounting for the effects of age and pathologic T and N classification (P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the difference in PKR expression in the TMA-1 (A and B) and TMA-2 (C and D) patients with (A and C) stage I and (B and D) stage I-IV NSCLC. The survival rate was significantly lower in the patients with low-level PKR expression (<176) than in those with high-level PKR expression (>=176).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox model assessing effects of covariates on overall survival

| TMA-1 | TMA-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Stages (N=231) | All Stages (N=224) | |||

| Characteristics | HRa | p-value | HR | p-value |

| A. Univariate Cox regression model | ||||

| Gender (male vs female) | 1.26 | 0.2 | 1.24 | 0.2 |

| Tobacco history (yes vs no) | 0.96 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 0.89 |

| Pathological TNM stage | ||||

| Stages II + III + IV vs I | 2.21 | <0.0001 | 2.4 | 0.002 |

| pT (T2 + T3 + T4 vs T1) | 2.61 | <0.0001 | 2.4 | 0.002 |

| pN (N1 + N2 vs N0) | 1.96 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.01 |

| pM (M1 + vs M0) | 1.92 | 0.24 | 1.5 | 0.32 |

| Histologic type (ACC vs SCC) | 1.39 | 0.07 | 1.36 | 0.17 |

| PKR expression | ||||

| High vs low | 0.27 | <0.0001 | 0.28 | <0.0001 |

| B. Multivariate Cox regression model | ||||

| Pathological TNM stage | ||||

| Stages II + III + IV vs I | 2.33 | 0.001 | 2.33 | 0.001 |

| pT (T2 + T3 + T4 vs T1) | 2.41 | <0.0001 | 2.41 | <0.0001 |

| pN (N1 + N2 vs N0) | 1.93 | 0.014 | 1.93 | 0.014 |

| PKR expression | ||||

| High vs low | 0.23 | <0.0001 | 0.22 | <0.0001 |

Hazard ratio

Validation of PKR biomarker in NSCLC tumors

We next validated our findings using same PKR antibody in a second TMA set (TMA-2) from 224 NSCLC tumor samples (146 ACCs and 78 SCCs). We confirmed that low-level PKR expression was correlated with the presence of lymph node metastasis (P = 0.044), and SCC versus ACC (P = 0.001) (data not shown). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 2 (B) show that low-level PKR expression was related to a significantly reduced probability of survival in the subgroup of patients in all-stage patients (B) (P < 0.0001). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that expression of PKR was significantly associated with overall survival (P < 0.0001; Table 3).

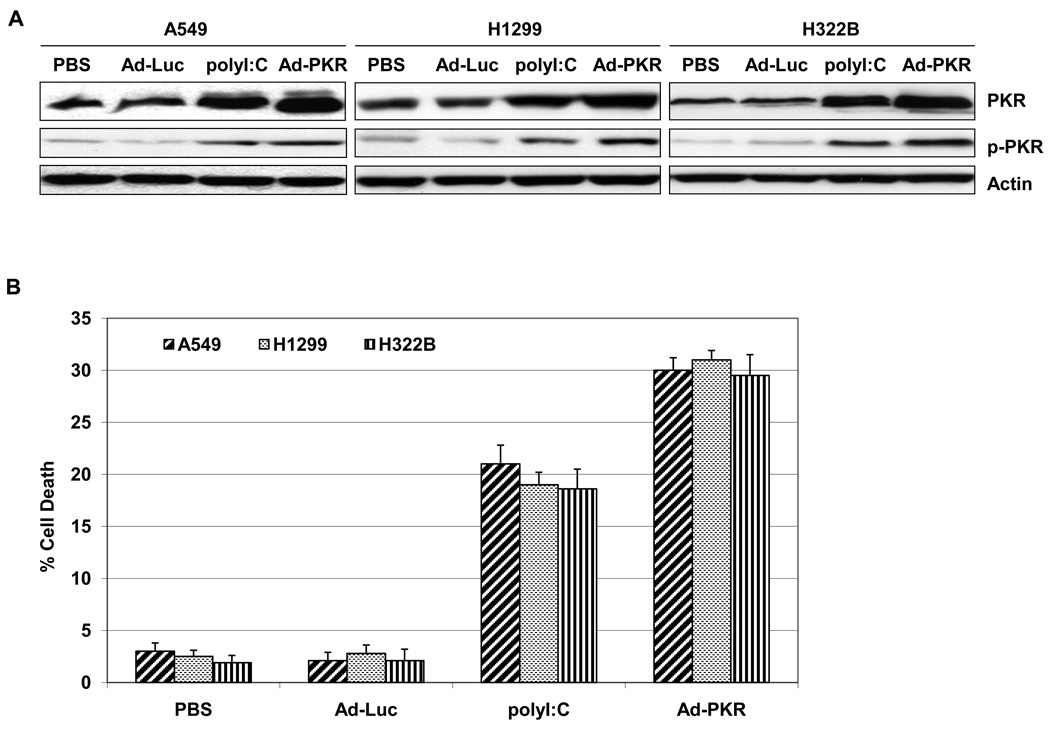

Induction of PKR causes cell death in lung cancer cell lines

We next determined whether induction of PKR cause cell death in lung cancer cell lines. We first analyzed the PKR and p-PKR expression in A549, H1299 and H322B lung cancer cells after treatment with PBS, Ad-Luc (2500 viral particle/cell), Ad-PKR (2500 viral particle/cell) or polyI:C (50 ng/ul), which is a synthetic dsRNA molecule that is a potent activator of PKR. Western blot analysis revealed that treatment of A549, H1299 and H322B lung cancer cells with polyI:C and Ad-PKR increased PKR and p-PKR levels (Fig. 3A). We next tested whether polyI:C or Ad-PKR induce cell death in A549, H1299 and H322B lung cancer cell lines. As shown by flow cytometric analysis of human lung A549, H1299 and H322B cancer cells, polyI:C or Ad-PKR induced cell death within 48 hours (Fig. 3B). In contrast, Ad-Luc was not toxic to A549, H1299 and H322B lung cancer cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Induction of PKR in human lung cancer cells causes cell death. (A) Western blot analysis of PKR and phospho-PKR protein expression in human lung (A549, H1299 and H322B) cancer cell lines. The expression of actin was used as a loading control. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of cell death in A549, H1299 and H322B cancer cells 48 hours after treatment with PBS, Ad-Luc (2500 viral particle/cell), Ad-PKR (2500 viral particle/cell), or polyI:C (50 ng/ul). Experiments were performed in triplicate; data represent the mean (SD).

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the expression of PKR in NSCLC and its relationship with the clinicopathologic parameters and prognosis of the disease. Expression of PKR was first evaluated in 88 normal tissues and 231 NSCLC tumors by immunohistochemistry using TMA-1. We found PKR to be expressed in both the cytoplasm and nuclei of normal bronchial epithelium, but just in the cytoplasm of NSCLC specimens. The differences between normal and NSCLC cell lines were further confirmed by confocal studies on cell lines (data not shown). We observed PKR to be mainly localized in the cytosol in cancer cell lines. We found a diffuse expression pattern of PKR, which is interesting since the function of PKR in the cytoplasm, but not the nucleus, has been previously defined. It has been shown that PKR protein is present in the cytoplasm of most cells in an inactive form (1–5). PKR molecules undergo a conformational change when binding to dsRNA or other activator molecules, thus allowing for dimerization and autophosphorylation at Thr446 and Thr451 and leading to activation of the kinase function (1–5). We have not been able to detect the active form of PKR (phospho-PKR) using several antibodies on our TMA-1 specimens and are thus seeking phospho-PKR antibodies for immunohistochemical staining.

Compared with findings in normal bronchial epithelium, reduction of PKR expression was found in 178 (77%) of 231 NSCLCs. We detected a significant association of low-level PKR expression with lymph node metastasis and observed that reduction of PKR was related to a lower probability of survival. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model analysis also showed that the PKR expression was significantly associated with overall survival after accounting for the effects of age and pathologic T and N classification. In our study, we had the opportunity to validate the use of PKR as a biomarker using additional NSCLC tumor samples (TMA-2). Here, for the first time, we show that low expression of PKR is related to poor prognosis and high expression of PKR is related to improved prognosis all-stage patients. Our data showed that a high level of PKR was an independent prognostic marker of survival in stage I and all-stage NSCLC patients. In a previous report, Roh et al. found that BAC patients with high PKR expression levels had significantly shorter survival durations than did patients with low PKR expression levels (8). The results need to be confirming due to small samples (38 cases) and different antibody used in their study. A BAC tumor represents less that 1% of our cases, and because the lack of invasion we did not included in the TMAs. We will confirm the significant of PKR on BAC once we collect enough samples.

The mechanism by which PKR inhibits lung tumor progression is not clear yet. It has been shown that overexpression or activation of PKR in many cancer cells leads to apoptosis, which may be due to an increased phosphorylation of eIF2α, but also to the expression of proapoptotic factors such as Fas (28, 29). We speculate that PKR suppress tumor growth by phosphorylation of eIF2α. In our previous and current study, we have demonstrated that induction of PKR and phosphor-PKR in human lung cancer cell cause cell death (20–23). Further study need to determine the significant of phospho-PKR and phospho-eIF2α expression on these NSCLC tumors.

PKR activity in cancer is positively regulated by the cellular protein MDA-7 (melanoma differentiation-associated gene-7) (20, 23). We have reported that the tumor suppressor MDA-7 interacts physically with PKR, leading to rapid induction of expression of PKR and activation of its downstream targets, resulting in apoptosis induction in human lung cancer cells (20, 23). Ishikawa et al. reported a lack of a significant correlation between the MDA-7/IL-24 status and all patient characteristics, including pathologic stage, in patients with NSCLC (30). However, subset analyses showed that MDA-7/IL-24 expression was a significant factor predicting a favorable prognosis for ACC (30).

Our results indicate that loss of PKR expression is correlated with a more aggressive behavior all-stage disease and that a high PKR expression predicts a subgroup of patients with a favorable outcome. Our future goal is to determine whether PKR mRNA level correlate with its protein expression in lung tumor samples. We will also attempt to determine the PKR protein expression, gene mutation and DNA copy number by various molecular techniques, such as the reverse phase protein array (RPPA), mutational analysis, FISH, and microarray.

Acknowledgements

We thank Denise M. Woods and Lakshimi Kakarala for their technical assistance and Wanda L Reese and Deborah L Waits for their assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Grant support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: SPORE 5P50-CA70970-04 (J.A. R., I.I.W), Department of Defense W81XWH-07-1-0306 (J.A.R. and I.I.W.), and The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Support Core Grant (2 P30 CA016672); and by support from the Homer Flower Gene Therapy Fund, the Charles Rogers Gene Therapy Fund, the Margaret Wiess Elkins Endowed Research Fund, and the George P. Sweeney Esophageal Research Fund.

Abbreviations

- PKR

RNA-dependent protein kinase

References

- 1.Barber GN. Host defense, viruses and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:113–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams BRG. Signal integration via PKR. Sci STKE. 2001;89:RE2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.89.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katze MG. The war against the interferon-induced dsRNA-activated protein kinase: can viruses win? J Interferon Res. 1992;12:241–248. doi: 10.1089/jir.1992.12.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagus R, Joshi B, Barber GN. PKR, apoptosis and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gil J, Esteban M. Induction of apoptosis by the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR): mechanism of action. Apoptosis. 2000;5:107–114. doi: 10.1023/a:1009664109241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terada T, Maeta H, Endo K, Ohta T. Protein expression of double-stranded RNA activated protein kinase in thyroid carcinomas: correlations with histologic types, pathologic parameters, and Ki-67 labeling. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:817–821. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.8443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SH, Gunnery S, Choe JK, Mathews MB. Neoplastic progression in melanoma and colon cancer is associated with increased expression and activity of the interferon-inducible protein kinase, PKR. Oncogene. 2002;21:8741–8748. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roh MS, Kwak JY, Kim SJ, et al. Expression of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase in small-size peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung. Pathol Int. 2005;55:688–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haines GK, 3rd, Becker S, Ghadge G, Kies M, Pelzer H, Radosevich JA. Expression of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (p68) in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck region. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:1142–1147. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880220098012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh C, Haines GK, Talamonti MS, Radosevich JA. Expression of p68 in human colon cancer. Tumour Biol. 1995;16:281–289. doi: 10.1159/000217945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haines GK, Ghadge G, Thimmappaya B, Radosevich JA. Expression of the protein kinase p-68 recognized by the monoclonal antibody TJ4C4 in human lung neoplasms. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1992;62:151–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02899677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haines GK, Ghadge GD, Becker S, et al. Correlation of the expression of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (p68) with differentiation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1993;63:289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02899275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haines GK, Cajulis R, Hayden R, Duda R, Talamonti M, Radosevich JA. Expression of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (p68) in human breast tissues. Tumour Biol. 1996;17:5–12. doi: 10.1159/000217961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haines GK, Panos RJ, Bak PM, et al. Interferon-responsive protein kinase (p68) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen are inversely distributed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 1998;19:52–59. doi: 10.1159/000029974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimada A, Shiota G, Miyata H, et al. Aberrant expression of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase in hepatocytes of chronic hepatitis and differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4434–4438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terada T, Ueyama J, Ukita Y, Ohta T. Protein expression of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) in intrahepatic bile ducts in normal adult livers, fetal livers, primary biliary cirrhosis, hepatolithiasis and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Liver. 2000;20:450–457. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020006450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beretta L, Gabbay M, Berger R, Hanash SM, Sonenberg N. Expression of the protein kinase PKR in modulated by IRF-1 and is reduced in 5q-associated leukemias. Oncogene. 1996;12:1593–1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hii SI, Hardy L, Crough T, et al. Loss of PKR activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:329–335. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murad JM, Tone LG, de Souza LR, De Lucca FL. A point mutation in the RNA-binding domain I results in decrease of PKR activation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;34:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pataer A, Vorburger SA, Barber GN, et al. Adenoviral transfer of the melanoma differentiation-associated gene 7 (mda7) induces apoptosis of lung cancer cells via up-regulation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) Cancer Res. 2002;62:2239–2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vorburger SA, Pataer A, Yoshida K, et al. Role for the double-stranded RNA activated protein kinase PKR in E2F-1-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:6278–6288. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holzen UV, Bocangel D, Pataer A, et al. Role for the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR in Ad-TNF-alpha gene therapy in esophageal cancer. Surgery. 2005;138:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pataer A, Vorburger SA, Chada S, et al. Melanoma differentiation-associated gene-7 protein physically associates with the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR. Mol Ther. 2005;11:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Holzen U, Pataer A, Raju U, et al. The double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase mediates radiation resistance in mouse embryo fibroblasts through nuclear factor kappaB and Akt activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6032–6039. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu W, Hofstetter W, Guo W, et al. JNK-deficiency enhanced oncolytic vaccinia virus replication and blocked activation of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:616–624. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prudkin L, Behrens C, Liu DD, et al. Loss and reduction of FUS1 protein expression is a frequent phenomenon in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:41–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Lyon: IARC; 2004. Pathology and genetics: tumours of the lung, pleura and heart, editors. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Der SD, Yang YL, Weissmann C, Williams BR. A double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway mediating stress-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3279–3283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balachandran S, Kim CN, Yeh WC, Mak TW, Bhalla K, Barber GN. Activation of the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR, induces apoptosis through FADD-mediated death signaling. EMBO J. 1998;17:6888–6902. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishikawa S, Nakagawa T, Miyahara R, et al. Expression of MDA-7/IL-24 and its clinical significance in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1198–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]