Abstract

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near 7 loci have been associated with liver function tests or with liver steatosis by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In this study we aim to test whether these SNPs influence the risk of histologically-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). We tested the association of histologic NAFLD with SNPs at 7 loci in 592 cases of European ancestry from the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network and 1405 ancestry-matched controls. The G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 was associated with increased odds of histologic NAFLD (odds ratio [OR] = 3.26, 95% confidence intervals [CI] = 2.11-7.21; P = 3.6 × 10−43). In a case only analysis of G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 was associated with a decreased risk of zone 3 centered steatosis (OR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.36-0.58; P = 5.15 × 10−11). We did not observe any association of this variant with body mass index, triglyceride levels, high- and low-density lipoprotein levels, or diabetes (P > 0.05). None of the variants at the other 6 loci were associated with NAFLD.

Conclusion

Genetic variation at PNPLA3 confers a markedly increased risk of increasingly severe histological features of NAFLD, without a strong effect on metabolic syndrome component traits.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common cause of chronic liver disease. It is frequently associated with obesity, insulin resistance and features of the metabolic syndrome.1,2 The histologic phenotype of NAFLD extends from fatty liver to steatohepatitis.3 Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is characterized by hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and cytologic ballooning with varying degrees of fibrosis.3 NASH progresses to cirrhosis in approximately 15% of subjects.4 The factors that predispose to the risk of progression and the mechanisms that drive disease progression in those who develop cirrhosis are not well understood.

Recently, genetic association studies successfully identified genetic variants that associate with many polygenic diseases and traits.5 Seven genetic variants were associated with liver function tests (LFTs) (near PNPLA3, CPN1, ABO, GPLD1, JMJD1C, GGT1, HNF1A).6,7 An allele in PNPLA3-(rs738409[G] encoding L148M) was also associated with an increased risk of hepatic steatosis by magnetic resonance spectroscopy.6,8,9 PNPLA3, also known as patatin like phospholipase-3 or adiponutrin, is expressed in adipose tissue10 and has recently been shown to function as a lipase.11 Elevations of liver enzymes are nonspecific markers of hepatocyte injury and liver imaging is an indirect measure of liver fat that can be influenced by other components in liver, including glycogen, iron and water content.

The objective of the current study was to determine the impact of genetic variants that associate with LFTs or liver steatosis by magnetic resonance spectroscopy on histologically-defined NAFLD in subjects with histologically-characterized NAFLD from the NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN).

Participants and Methods

Participants

This study focused on a test population of subjects with varying severity of histology diagnosed NAFLD and compared them to an ancestry-matched control population. The test population was comprised of adult patients from a cohort of subjects from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) NASH CRN collected from 8 clinical centers in the United States (see Supporting Methods). To minimize the effects of stratification on genetic associations, only individuals of European non-Hispanic ancestry were included for this genetic study. For selection criteria of individuals from the NASH CRN sample for analyses, see Supporting Methods.

A control population from the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (MIGen) cohort was used for matching to the test samples. As previously described,12 these samples were collected from 6 centers in the United States and Europe (see Supporting Methods).

We obtained publicly available genome-wide association meta-analysis data generated by the Global Lipids Genetics consortium (for lipid levels),13 and the DIAGRAM (DIAbetes Genetic Replication And Meta-analysis consortium) (for type 2 diabetes [T2D]),14 and also obtained unpublished meta-analysis results from the GIANT (Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits Consortium) (for anthropometric measures of obesity).15,16

Measurement of Phenotypes

Detailed clinical and demographic information including age, gender, race, comorbidities such as T2D mellitus or hypertension, and relevant laboratory data including the lipid profile and liver enzymes were obtained in all cases in the test group from the NASH CRN records. Anthropometric measurements were obtained by specifically trained personnel at each center using standardized methodology. In MIGen, clinical information from baseline values were made available and used for analysis.12

Liver histology was evaluated in the test group according to the NASH CRN scoring system.3 Steatosis distribution was categorized into zone 3 centered, zone 1 centered, azonal or panacinar. The presence or absence of steatohepatitis was recorded independently. Predominantly macrovesicular steatosis was scored from grade 0-3. Inflammation was graded from 0-3 and cytologic ballooning from 0-2. The fibrosis stage was assessed from a Masson trichrome stain and classified from 0-4 according to the NASH CRN criteria.3 In this classification, stage 3 represents bridging fibrosis and stage 4 represents cirrhosis.

Sample Curation and Genotyping

The NASH CRN samples were genotyped using the iPLEX Sequenom MassARRAY platform. A total of 131 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped in the NASH CRN samples using the platform iPLEX Sequenom MassARRAY platform and the 127 that passed quality control criteria (see Supporting Methods) were used for analyses. For the MIGen cohort, 1405 control samples of self reported Caucasian ancestry were genotyped on the Affymetrix 6.0 product and used for analysis after quality control filtering (see Supplementary Methods) using previously described criteria.12 To account for the uncertainty inherent in such imputations, an association analysis program (SNPTEST17) was used to test association with allele “dosage” rather than dichotomous genotypes. PLINK output files for NASH CRN cases were converted to SNPTEST format for these association analyses.

Assessment and Identification of Ancestry-based Confounders

Genetic ancestry was initially explored by principal component analysis of the genome-wide data set from MIGen using Eigenstrat.18 The first principal component was the most significant and correlated with that previously reported along the Northwest-Southeast axis within Europe.19 It was confirmed that the self-reported country of origin in the MIGen cohort correlated with this principal component corroborating its validity.12 From this analysis, 120 SNPs that were genotyped in the MIGen cohort and distinguished ancestry along the first principal component were chosen and genotyped in the NASH CRN test group, so that these samples could be matched to the MIGen control sample. Using PLINK,20 individuals were matched based on identity by state distance which was calculated using these 120 SNPs; individuals were deemed to be part of the same population and could be matched if the pair-wise population concordance test statistic between them was > 1 × 10−3.

To control further for confounding by ancestry, we determined principal components in the NASH CRN and MIGen cohorts based on the genotypes of the 120 ancestry informative markers, using the smartpca program within Eigenstrat.18 Five eigenvectors were generated for each individual in both the NASH CRN test group (only individuals of white, non-Hispanic origin) and the MIGen controls and used as covariates to control for ancestry in subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analyses

After matching NASH CRN cases to MIGen controls (described above), we analyzed 12 test SNPs for association to histologic traits using logistic regression. We controlled for age, age2 and gender and used the first 5 principal components of genetic ancestry as covariates in SNPTEST.17 We report P values, ORs and confidence intervals (CIs) from analyses using dosages from imputed genotypes in MIGen. For NASH CRN case-only analyses, continuous variables were inverse normally transformed and association analyses was completed using regression in PLINK with the same covariates as in the case-control analysis. Dichotomous variables were tested for association in the NASH CRN case-only analysis using logistic regression in PLINK with the same covariates as above. For analyses in MIGen only, continuous variables were inverse normally transformed and association analyses were completed using regression in SNPTEST with the same covariates as above. Dichotomous variables were tested for association in MIGen using logistic regression in SNPTEST. We tested for interactions between the SNPs and age, gender and database (NAFLD or PIVENS) and these were not significant. We compared mean height, weight, body mass index (BMI), triglyceride levels, high-density lipoprotein levels, low-density lipoprotein levels, total cholesterol levels, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure in individuals with NASH versus those without NASH, and in those with fibrosis versus no fibrosis, using a t test with equal variances for normally distributed traits (all but triglycerides [Tg]) or a Wilcoxon rank sum test (for Tg). We compared trait values between the NASH CRN and MIGen samples using a t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test or chi-squared analyses.

Results

Association of Genetic Variants That Influence LFTs With Histologically-confirmed NAFLD in a Case-Control Analysis

We selected 12 SNPs from 7 loci that have been reported to associate with steatosis by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (PNPLA3)6 or with elevated liver tests (variants in or near PNPLA3, CPN1, ABO, GPLD1, JMJD1C, GGT1, HNF1A).7 We genotyped these SNPs in 678 individuals with NAFLD from the NASH Clinical Research Network, and compared these genotypes with data from 1405 ancestry-matched controls from the MIGen study (characteristics of the participants can be found in Supporting Table 1).

We first tested the variants for an effect on overall histologic NAFLD. The G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 was strongly associated with an increased risk of histologic NAFLD (OR = 3.26, 95% CI = 2.11-7.21; P = 3.6 × 10−43; Table 1). The same allele associated with steatosis >5% (OR = 3.12, 95% CI = 2.67-3.64; P = 1.11 × 10−46), lobular inflammation (OR = 3.08, 95% CI = 2.64-3.57; P = 1.83 × 10−47), hepatocellular ballooning (OR = 3.21, 95% 2.68-3.82; P = 4.19 × 10−38) NASH (OR = 3.26, 95% CI = 2.76-3.85; P = 2.06 × 10−44) and fibrosis (OR = 3.37, 95% CI = 2.85-3.97; P = 3.62 × 10−46) (Supporting Table 2). The similarity in the effects on overall histologic NAFLD and the subcomponents are due to a high degree of inter-relatedness of these phenotypes in the NASH CRN cohort (Supporting Table 1). All individuals in the NASH CRN sample with histology have at least some component of disease beyond simple steatosis including lobular inflammation, ballooning, or fibrosis indicating the presence of more advanced NAFLD. The remaining SNPs, including other variants associated with elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), were not strongly associated with histologic NAFLD (Table 1). Controlling for BMI, T2D, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein and TGs in these analyses did not noticeably affect any of the ORs, suggesting that these factors are not confounding the association of the SNPs with NAFLD (data not shown). Further, we controlled for the PNPLA3 variant rs738409 in analyses of the other two PNPLA3 variants (rs2294918 and rs2281135, which are both partially correlated with rs738409, with r2 = 0.18 and 0.61, respectively). Adding rs738409 into the analytical model reduced the ORs for the other two PNPLA3 SNPs to approximately 1, with a loss of statistical significance. This result suggests that the signals of association at these two SNPs are not independent of the stronger signal of association of rs738409 (data not shown). The effect of rs738409 on histologic NAFLD in gender-specific analyses in the NASH CRN/MIGen cohort was higher in women (OR = 4.05, 95% CI = 3.20-5.14) than in men (OR = 2.50, 95% CI = 1.95-3.20), but gender-specific analyses in additional, population-based cohorts would be needed to test whether there is a true and reproducible interaction between rs738409 and gender.

Table 1. Association of SNPs With Histologic Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver disease (NAFLD).

| Nearby Gene | SNP | Chr/Position | Effect/Other Allele | Effect Freq Cases NASH CRN | Effect Freq Controls MIGen | Direction original effect | Direction Same | Histologic NAFLDf(n = 592) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Pval | ||||||||

| PNPLA3 | rs738409 | 22/42656060 | G/C | 0.50 | 0.22 | G increase steatosis | yes | 3.26 (2.11-7.21) | 3.60E-43 |

| PNPLA3 | rs2294918 | 22/42673449 | A/G | 0.26 | 0.42 | G increase steatosis | yes | 0.49 (0.33-0.66) | 2.00E-16 |

| PNPLA3 | rs2281135 | 22/42663903 | A/G | 0.36 | 0.18 | T increase ALT | yes | 2.43 (2.26 - 2.60) | 1.67E-24 |

| CPN1 | rs7068215* (r2 = 0.889) | 10/101849860 | G/A | 0.38 | 0.40 | G increase ALT | no | 0.87 (0.77-1.00) | 6.76E-02 |

| CPN1 | rs2862990* (r2 = 0.82) | 10/101866354 | T/C | 0.40 | 0.39 | T increase ALT | yes | 1 (0.87-1.18) | 9.72E-01 |

| CPN1 | rs1597086 | 10/101943695 | C/A | 0.40 | 0.41 | C increase ALT | no | 0.96 (0.84-1.12) | 5.71E-01 |

| CPN1 | rs1591741 | 10/101966491 | C/G | 0.41 | 0.41 | C increase ALT | yes | 0.97 (0.82-1.12) | 6.98E-01 |

| ABO | rs657152 | 9/135129086 | A/C | 0.35 | 0.40 | G increase ALP | yes | 0.82 (0.67-0.97) | 9.12E-03 |

| GPLD1 | rs9467160 | 6/24549725 | A/G | 0.29 | 0.25 | A increase ALP | yes | 1.07 (0.90-1.23) | 4.50E-01 |

| JMJD1C | rs12355784 | 10/64791571 | A/C | 0.50 | 0.48 | A increase ALP | yes | 1 (0.84-1.15) | 9.54E-01 |

| GGT1 | rs4820599 | 22/23320213 | G/A | 0.30 | 0.28 | G increase GGT | yes | 1.12 (0.94 -1.37) | 1.83E-01 |

| HNF1A | rs2259816 | 12/119919970 | T/G | 0.39 | 0.36 | A increase GGT | yes | 1.19 (1.00 -1.45) | 2.79E-02 |

Nearby gene, gene nearest SNP used in analyses; Chr/Position, the chromosome and position (in NCBI Build 36) of SNP used in analyses; Effect allele, the allele for which the Odds Ratio is reported; Other allele, the non-effect allele at the SNP locus; Effect Freq Cases, frequency of the effect allele in NASH cases; Effect Freq Controls, frequency of the effect allele in controls; 95%CI, lower and upper 95% confidence intervals for the odds ratio; Pval, P-value for association; Direction of effect, direction relative to original association with increases steatosis or LFTs.

Results imputed using IMPUTE and analyzed using SNPTest.

Alternate correlated SNPs were used (r2 to rs1597390 shown in parentheses).

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; AIKPhos, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transpeptide.

Effects of the rs738409 PNPLA3 Variant on Specific Features of NAFLD in a Case-Only Analysis of Individuals From the NASH CRN

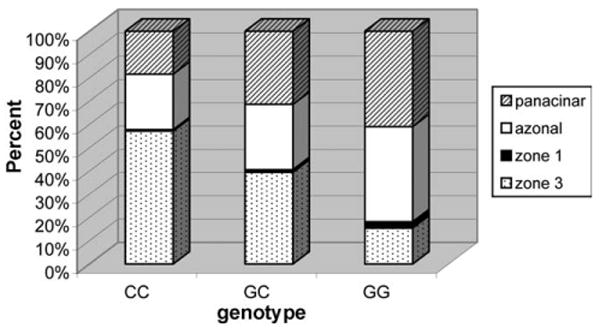

To determine whether the G allele of rs738409 is associated with particular histologic characteristics in individuals selected for fatty liver disease, we next performed comparisons within the NASH CRN sample. Individuals within the NASH CRN who carry G alleles of rs738409 have a decreased odds for having zone 3 centered steatosis overall (OR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.36-0.58; P = 5.16 × 10−11; Fig. 1, Table 2A). In particular, there was a decreased odds of having zone 3 centered steatosis compared with zone 1 centered steatosis (OR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.07-0.70; P = 0.01), compared with azonal steatosis (OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.30-0.57; P = 6.7 × 10−8 and compared with panacinar steatosis (OR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.25-0.48; P = 2.4 × 10−10; Table 2A). Individuals that carry the G allele of rs738409 also have a higher odds of having a lobular inflammation score of ≥2 versus <2 (OR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.12-1.78; P = 0.0031; Table 2A). Association was not seen with ballooning, NASH diagnosis overall in the NASH CRN case only analysis (Table 2A) but in comparing moderate versus no steatosis and severe versus no steatosis there was a trend towards significance (Table 2A). Evaluation of overall steatosis ≥5% versus <5% or overall lobular inflammation versus none could not be done due to the high prevalence of these traits in the NASH CRN.

Fig. 1.

Fat localization versus rs738409 genotype class within the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH-CRN) sample. For each genotype class, the percentage of individuals with fat localization in various categories is shown.

Table 2. Effects of the G Allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 on Metabolic and Histologic Traits.

| A. Histologic traits in NASH-CRN only n = 592) | B. Metabolic traits in NASH-CRN NAFLD database only (n = 516) | C. Metabolic traits in MIGen only (n = 1405) | D. Metabolic traits in large scale meta analyses* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Pval | Trait | Beta/Odds Ratio (Std Error/95% CI) | Pval | Trait | Beta/Odds Ratio (Std Error/95% CI) | Pval | Trait | N | Zscore/Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Pval |

| Ballooning | 0.92 (0.72-1.18) | 5.16E-01 | Height (cm) | −0.084 (−0.041) | 3.79E-02 | Height (cm) | 0.011 (−0.034) | 7.59E-01 | BMI (kg/m2) | 32521 | −1.542 | 1.41E-01 |

| Fibrosis | 1.34 (1.01-1.78) | 4.44E-02 | BMI (kg/m2) | −0.180 (−0.057) | 1.75E-03 | BMI (kg/m2) | 0.005 (−0.045) | 9.12E-01 | WC(cm) | 38570 | 0.38 | 7.00E-01 |

| NASH | 1.14 (0.86-1.51) | 3.76E-01 | Weight (kg) | −0.191 (−0.054) | 4.30E-04 | Weight (kg) | −0.009 (−0.042) | 8.30E-01 | WHR(cm) | 37660 | 0.484 | 6.30E-01 |

| zone3 steatosis | 0.46 (0.36-0.58) | 5.16E-11 | WC(cm) | −0.238 (−0.058) | 4.44E-05 | WC(cm) | (N/A) N/A | N/A | HDL-C (mg/dL) | 19794 | −2.488 | 1.30E-02 |

| moderate steatosis | 1.13 (0.87-1.47) | 3.66E-01 | Diabetes | 0.716 (0.551-0.931) | 1.25E-02 | Diabetes | 1.326 (0.8252-2.1308) | 2.53E-01 | LDL-C (mg/dL) | 19648 | −0.827 | 4.08E-01 |

| severe steatosis | 1.26 (0.93-1.70) | 1.37E-01 | TG (mg/dL) | −0.266 (−0.062) | 2.08E-05 | TG (mg/dL) | 0.280 (−0.045) | 5.37E-01 | TG (mg/dL) | 19840 | 1.464 | 1.43E-01 |

| lobular inflam ≥2 vs <2 | 1.42 (1.12-1.78) | 3.16E-03 | LDL-C (mg/dL) | −0.003 (−0.065) | 9.69E-01 | LDL-C (mg/dL) | −0.038 (−0.044) | 3.85E-01 | Diabetes | 4549 cases /5579 controls | 1.045 (0.973-1.122) | 2.30E-01 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 0.150 (−0.059) | 1.08E-02 | HDL-C (mg/dL) | −0.003 (−0.044) | 9.46E-01 | |||||||

| HTN | 0.831 (0.645-1.072) | 1.54E-01 | HTN | 1.068 (0.8643-1.3198) | 5.45E-01 | |||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.058 (−0.062) | 3.53E-01 | SBP (mmHg) | 0.069 (−0.047) | 1.42E-01 | |||||||

| DBP (mmHg) | −0.136 (−0.061) | 2.63E-02 | DBP (mmHg) | 0.049 (−0.048) | 2.99E-01 | |||||||

| MetSyn | 0.787 (0.615-1.006) | 5.60E-02 | MetSyn | N/A (N/A) | N/A | |||||||

Ballooning, individuals with ballooning on histology (vs those without ballooning); fibrosis, individuals with any fibrosis on histology (vs those without fibrosis); NASH, individuals with probable or definite NASH on histology (vs those without NASH); zone 3 steatosis, individuals with zone 3 steatosis (vs other patterns (zone 1, azonal, and panacinar) combined); moderate steatosis, moderate vs mild steatosis; severe steatosis, severe vs mild steatosis; lobular inflam >2 vs <2, lobular inflammation of vs <2; Beta/Odds Ratio, for continuous phenotypes we used the inverse normal value as the phenotype; for dichotomous traits the effect is shown as an odds ratio of association; Std Error/95% CI, standard error of the phenotype is shown if continuous; 95% confidence interval is shown if dichotomous; Pval, P for association; Zscore/Odds Ratio, shown is the z score or odds ratio for conitnuous and dichotomous traits respectively.

BMI, WC, WHR data from Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits Consortium (GIANT), HDL, LDL, TG data from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium, Diabetes data from DIAbetes Genetic Replication And Metaanalysis consortium (DIAGRAM).

Abbreviations: HTN, hypertensions; SBP systolic blood pressure; DBP diastolic blood pressure; Metsyn, metabolic syndrome.

Specificity of Effects on Metabolic Disease

In light of the fact that fatty liver disease is closely associated with the metabolic syndrome, we considered the possibility that the association with NAFLD could be mediated by associations with aspects of the metabolic syndrome. If the effect of rs738409 on NAFLD were indirect and mediated by other metabolic phenotypes, the G allele of rs738409 would be associated with an unfavorable metabolic profile, including increased obesity, dyslipidemia or T2D. We therefore tested the association of this allele with features of the metabolic syndrome in the NASH CRN sample; because of ascertainment on glucose intolerance in the PIVENS (Proglitazone versus vitamin E versus placebo for treatment of non-diabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatis) trial (see Supporting Methods), we excluded the PIVENS samples from these analyses. Interestingly, among patients selected for NAFLD, the G allele of rs738409 is actually associated with a favorable metabolic profile including decreased BMI, weight, waist circumference (WC), and triglyceride levels (TG) as well as increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and diastolic blood pressure (P values = 0.03 to 2.1 × 10−5) and decreased risk of T2D (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.55-0.93; P = 0.01) (Table 2B). Although individuals with severe liver disease may have weight loss, impaired lipid synthesis and decreased blood pressure, differences in multiple metabolic parameters between individuals with NASH/fibrosis versus those without these features were not significant in this sample (data not shown). Overall then, these results argue strongly against rs738409 increasing risk of NAFLD indirectly through an effect on these components of metabolic syndrome.

To test for an effect of the PNPLA3 variant on metabolic syndrome components in samples that were not ascertained for fatty liver disease, we also tested rs738409 for association of the traits that were available within the MIGen controls, and did not observe any associations (P = 0.25-0.95; Table 2C). We also examined the association of this SNP in published meta-analyses with BMI, waist circumference (WC), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides, and T2D risk. Specifically, we obtained the association results of this variant in large published meta-analyses from several consortia: DIAGRAM14 (T2D, n = 10,128), GIANT15,16 (BMI, WC, WHR, n = 32,521-38,570) and the Global Lipid Genetics Consortium(13) (HDL-C, LDL-C and TG, n = 19,648 to 19,840). We observed that the G allele of rs738409 is not strongly associated with BMI, WC, WHR, LDL-C, TG, HDL-C or T2D risk in these large meta-analyses (P values = 0.013-0.70; Table 2D).

Specificity and Replicability of Associations With Liver Enzyme Levels

Finally, we considered whether the lack of association of the other variants to NAFLD might imply that the original associations with LFTs were not readily replicable. To determine whether we could replicate the associations with LFTs (at least in individuals selected for liver disease in the NASH CRN), we tested them for associations to ALT, alkaline phosphatase (AlkPhos) in the NASH CRN sample. We found that variants near ABO and GGT1 were, as expected, specifically associated with AlkPhos (P = 2.17 × 10−6) and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels (P = 0.0006), respectively (Table 3). Thus, the lack of association with NAFLD for these variants suggests that not all variants that are reproducibly associated with LFTs will also show association with NAFLD. We did not see evidence for association of variants near HNF1A with GGT or variants near GLPD1 or JMJD1C with AlkPhos, which could be due to a lack of true association, lack of power in our samples, or a lack of association with LFTs in individuals selected for NAFLD.

Table 3. Associations of SNPs With Liver Function Tests in NASH-CRN Sample.

| Nearby Gene | SNP | Phenotype | Effect/Other Allele | Beta | Std Error | Pval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNPLA3 | rs738409 | ALT | G/C | 0.089 | 0.050 | 7.64E-02 |

| CPN1 | rs7068215 | ALT | G/A | −0.051 | 0.055 | 3.55E-01 |

| ABO | rs657152 | AlkPhos | A/C | −0.254 | 0.053 | 2.17E-06 |

| GPLD1 | rs9467160 | AlkPhos | A/G | 0.085 | 0.057 | 1.33E-01 |

| JMJD1C | rs12355784 | AlkPhos | A/G | −0.007 | 0.053 | 8.88E-01 |

| GGT1 | rs4820599 | GGT | G/A | 0.201 | 0.058 | 6.08E-04 |

| HNF1A | rs2259816 | GGT | T/G | −0.078 | 0.056 | 1.64E-01 |

Nearby gene, gene nearest SNP used in analyses; Chr/Position, the chromosome and position (in NCBI Build 36) of SNP used in analyses; Effect allele, the allele for which the beta is reported; Other allele, the non-effect allele at the SNP locus; Beta, beta value for continuous phenotypes using inverse normal value as phenotype; Std Error, standard error of the phenotype; Pval, P value for association; AlkPhos, Alkaline phosphatase (n = 677); ALT, alanine aminotransferase (n = 667); GGT, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (n = 662).

In conclusion, we extend previous work by showing that variants near PNPLA3, but not at the other 6 loci tested, specifically associate with histologic NAFLD. A recent study21 reported an association between histologic NAFLD and variation near PNPLA3, although the evidence for association was much more modest than that described here, likely because of smaller sample size. Other LFT-associated SNPs have not to our knowledge been evaluated for their effects on histologic NAFLD. We also show that variants near PNPLA3 do not exert their effects on NAFLD indirectly by affecting component traits of the metabolic syndrome. Thus, we show that metabolic syndrome component traits and histologic features of NAFLD can be genetically dissociated.

The G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3, but not variants at other loci we tested, associates with histologic NAFLD compared to controls from the MIGen sample (Table 1). This specificity to PNPLA3 is a novel finding and suggests that not all variants associated with increased liver enzyme levels, including ALT, will associate with NAFLD-related phenotypes. In our studies, we did not see any evidence for association with histology-based NAFLD of the locus near CPN1 that was previously reported to associate with ALT. This lack of association may be due to variants at this locus not being truly associated with ALT (for example due to stratification given the mixed ancestry in the original study) or because it associates with some non-NAFLD related phenotypes that are associated with increased ALT levels or may be specific to the original population tested. It is possible that misclassification of cases as controls due to the lack of liver histology in the MIGen sample can bias results to the null. However, the remarkably strong association of variants around PNPLA3 with case-control status suggests that the NASH CRN/MIGen sample is quite sensitive for identifying variants that associate with histologic NAFLD and indeed resulted in associations of larger magnitude and much greater statistical significance than in recently reported studies.8,9,21 Thus, our negative results suggest that, if the variants at the other loci have any effect at all on NAFLD, these effects are much weaker than those of PNPLA3. Our strong replication of several associations with AlkPhos and GGT in the NASH CRN sample also suggests that lack of power or differences in samples are unlikely to fully explain the lack of association of the CPN1 variant with NAFLD. These results emphasizes the importance of confirming that variants associated with indirect measures of NAFLD (such as radiologic measures of liver fat or LFTs) are associated with histology-based NAFLD before concluding that such variants influence development of NAFLD itself. We also show through conditional analysis that the association of PNPLA3 variants rs2294918 and rs2281135 are likely not independent of the stronger signal of association at the nearby rs738409 variant.

NAFLD is one of the best markers of the metabolic syndrome1,22 which consists of having three or more of the following: impaired fasting glucose, central obesity, dyslipidemia and hypertension. Interestingly, we found that the G allele of rs738409 at PNPLA3, even though it strongly associates with NAFLD, does not associate with metabolic syndrome traits in the MIGen controls or in large-scale meta-analyses for BMI, WC, WHR, lipids and T2D. Since lack of association can always be due to lack of power, a small effect on metabolic traits cannot be ruled out. Other smaller studies have not seen an association of the G allele of rs738409 with fasting glucose, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, BMI or insulin sensitivity.6,21 However, the lack of effect of these variants on metabolic traits in large meta-analyses for these traits suggests that this variant does not have strong effects on these traits compared to its effect on NAFLD. Further, analyses using BMI, T2D, HDL-C, LDL-C and triglycerides as covariates in the NASH CRN/MIGen analyses did not change the strength of association of SNPs in or near PNPLA3, suggesting that variation in these traits is not confounding the relationship of these SNPs and histologic NAFLD. In addition, the striking inverse correlations in the NASH CRN sample of the NAFLD-increasing allele with features of metabolic syndrome risk factors further rule out an indirect effect on NAFLD via metabolic syndrome risk factors. Indeed, this inverse association may be due to the ascertainment on NAFLD: individuals with the high-risk allele of rs738409 may accumulate enough steatosis and subsequent damage to their liver to develop NAFLD at lower levels of metabolic disease than individuals who do not carry this allele. Taken together, these results suggest that risk for metabolic disease can be dissociated from fatty liver disease risk conferred by rs738409 and that some mechanisms by which fat is deposited in liver may be related to the presence of obesity, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance and hypertension whereas others may be more reflective of endogenous genetic predispositions to fat accumulation in the liver. Thus, through a genetic analysis we may be able to dissociate otherwise epidemiologically related traits, and such distinctions may eventually help us to predict which treatments aimed at which pathways might be most effective for different but related metabolic diseases.

Discussion

We extend previous work by showing that the G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 is associated with histologic steatosis as well as NASH, fibrosis and cirrhosis. Particularly striking is the association of the G allele of rs738409 with decreased likelihood of having a zone 3 centered distribution of steatosis. Zone 3 centered steatosis is more often observed in early stages of NAFLD and is less likely to be associated with ballooned hepatocytes, Mallory-Denk bodies or advanced fibrosis than panacinar or azonal distributions of steatosis.23 Zone 3 hepatocytes are characterized by higher levels of glycolysis, liponeogenesis and ketogenesis than periportal zone 1 hepatocytes which in turn have a higher level of gluconeogenesis, urea synthesis, and bile acid and cholesterol synthesis.24-27 Although zone 3 hepatocytes may be metabolically well-suited for lipogenesis in the normal liver, in advanced disease the ability of this zone to buffer the energy overload may be overwhelmed and fat deposition throughout the liver may predominate. When the normal mechanisms that protect hepatocytes from fatty acid damage get overwhelmed, lipotoxicity, cell death and triggering of stellate cell activation ensue.28 These processes can lead to the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the liver and to the deposition of extracellular matrix, resulting in fibrosis and cirrhosis.28 Consistent with this hypothesis, the G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 is associated more frequently with diffuse fat deposition (not just limited to zone 3) it may promote NASH, fibrosis and cirrhosis throughout the liver.

One of the strengths of this work is that we were able to match cases of NAFLD with controls to enable us to find variants that associate with NAFLD. An alternative approach would have been to examine severity of phenotypes within the NAFLD sample alone. The case-control approach provided greater power: with fewer than 600 cases of NAFLD, we were able to show genetic associations of rs738409 with P values ranging from 1×10−38 to 1×10−47, whereas in a case-only analysis, our lowest P value was 5 × 10−11. This increased power by adding MIGen is due to the increased overall sample size as well as increased phenotypic breadth of the samples since few or no individuals in the NASH CRN just have just steatosis or no steatosis, respectively. The addition of these ancestry-matched controls did not appear to generate large numbers of false positives in that only variants near PNPLA3 strongly associated with NAFLD, whereas the other tested variants did not.

Limitations of this work include the ascertainment of the NASH CRN on the basis of NAFLD at one timepoint and the analysis of individuals of European ancestry; thus, results may not be directly translatable to differently ascertained samples of other ancestries or be the same over time. Although we have tried to assess the effect of the G allele of rs738409 in PNPLA3 in large meta-analyses, a small effect on metabolic syndrome components cannot be ruled out. Further the results may be affected by unmeasured confounders but the results are undiminished when controlling for measured confounders. The presence of liver disease in MIGen would cause misclassification and would bias our results towards the null, slightly reducing power compared with an equivalently sized sample known to be free of liver disease. However, this misclassification would not cause spurious associations, so the strong association between PNPLA3 and NAFLD/ NASH remains valid even in this setting. Finally, because many of the histologic subphenotypes of NAFLD are highly intercorrelated in the NASH CRN sample, further work will be needed to better characterize and possibly distinguish the specific effects of rs738409 on these phenotypes in patients with histologic NAFLD.

This is to our knowledge the first well-powered assessment of the effects on histology-based NAFLD of genetic variants previously associated with liver enzyme levels. Our results suggest that variation at PNPLA3 specifically and strongly influences the development of advanced NAFLD including NASH, fibrosis and cirrhosis. Given that PNPLA3 appears to be part of a family of enzymes that affect lipid metabolism, this suggests that altering lipid metabolism, particularly within the liver, can affect accumulation of fat and subsequent development of NAFLD. These results therefore suggest that certain inherited variations in lipid metabolism precede and could lead to the development of liver disease. Because this variant appears to not have a strong population effect on diabetes, obesity or serum lipid levels, the development of fatty liver disease can be at least partially dissociated from epidemiologically correlated variables. Thus, through genetic analyses, we may be able to delineate the causal pathways that lead to specific disease complications of metabolic risk factors such as NAFLD and, in the future, selectively target them for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the study participants without whom this research would be impossible. We would like to thank the NASH CRN, the MIGen consortium, the Global Lipids consortium, the GIANT consortium and the DIAGRAM consortium for sharing their data/samples. We would like to thank Dr Arun Sanyal for serving as a liason to the NASH CRN for this work. We would like to thank David E. Kleiner for critically reviewing the manuscript.

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants T32 DK07191-32 to Daniel Podolsky (for EKS), F32 DK079466-01 to EKS and NIH K23DK080145-01 to EKS and R01DK075787 to JNH. The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grants U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, U01DK061713), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Several clinical centers use support from General Clinical Research Centers or Clinical and Translational Science Awards in conduct of NASH CRN Studies (grants UL1RR024989, M01RR000750, M01RR00188, ULRR02413101, M01RR000827, UL1RR02501401, M01RR000065, M01RR020359). The MIGen study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's STAMPEED genomics research program.

Abbreviations

- AlkPhos

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

body mass index

- DIAGRAM

DIAbetes Genetic Replication And Meta-analysis consortium

- GIANT

Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits Consortium

- GGT

glutamyl transpeptidase

- GIANT

genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits Consortium

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- IBS

identity by state

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LFT

liver function test

- MIGen

Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH CRN

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- OR

odds ratio

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TG

triglycerides

- WC

waist circumference

- WHR

waist-to-hip ratio

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nakagawa T, Taniguchi H, Fujii K, et al. The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:722–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan JG, Zhu J, Li XJ, Chen L, Li L, Dai F, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for fatty liver in a general population of Shanghai, China. J Hepatol. 2005;43:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison SA, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:861–879. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan X, Waterworth D, Perry JR, Lim N, Song K, Chambers JC, et al. Population-based genome-wide association studies reveal six loci influencing plasma levels of liver enzymes. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotronen A, Johansson LE, Johansson LM, Roos C, Westerbacka J, Hamsten A, et al. A common variant in PNPLA3, which encodes adiponutrin, is associated with liver fat content in humans. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1056–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1285-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotronen A, Peltonen M, Hakkarainen A, Sevastianova K, Bergholm R, Johansson LM, et al. Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:865–872. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson LE, Johansson LM, Danielsson P, Norgren S, Johansson S, Marcus C, et al. Genetic variance in the adiponutrin gene family and childhood obesity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He S, McPhaul C, Li JZ, Garuti R, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, et al. A sequence variation (I148M) in PNPlA3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6706–6715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, Musunuru K, Ardissino D, Mannucci PM, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, Hu T, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willer CJ, Speliotes EK, Loos RJ, Li S, Lindgren CM, Heid IM, et al. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindgren CM, Heid IM, Randall JC, Lamina C, Steinthorsdottir V, Qi L, et al. Genome-wide association scan meta-analysis identifies three Loci influencing adiposity and fat distribution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price AL, Butler J, Patterson N, Capelli C, Pascali VL, Scarnicci F, et al. Discerning the ancestry of European Americans in genetic association studies. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sookoian S, Castano GO, Burgueno AL, Fernandez Gianotti T, Rosselli MS, et al. A nonsynonymous gene variant in adiponutrin gene is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity. J Lipid Res. 2009 doi: 10.1194/jlr.P900013-JLR200. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan JG, Zhu J, Li XJ, Chen L, Lu YS, Li L, et al. Fatty liver and the metabolic syndrome among Shanghai adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1825–1832. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalasani N, Wilson L, Kleiner DE, Cummings OW, Brunt EM, Unalp A. Relationship of steatosis grade and zonal location to histological features of steatohepatitis in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48:829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasse D. Dynamics of liver glycogen: the topochemistry of glycogen synthesis, glycogen content and glycogenolysis under the experimental conditions of glycogen accumulation and depletion. Histochemistry. 1975;45:237–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00507698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jungermann K, Heilbronn R, Katz N, Sasse D. The glucose/glucose-6-phosphate cycle in the periportal and perivenous zone of rat liver. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123:429–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb19786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teutsch HF, Lowry OH. Sex specific regional differences in hepatic glucokinase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;106:533–538. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jungermann K, Katz N. Functional specialization of different hepatocyte populations. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:708–764. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jou J, Choi SS, Diehl AM. Mechanisms of disease progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:370–379. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.