Abstract

Meningeal carcinomatosis (MC) is diffuse infiltration of the meninges by metastatic carcinoma. Though a known complication of solid tumours, it is rarely seen as a presenting feature of such cancers. Here, the authors describe the case of a 64-year-old lady who presented with rapid-onset hearing loss and progressive visual loss, among other cranial nerve palsies. A primary non-small cell lung cancer was later identified by CT, but the diagnosis of MC was only confirmed after cytological analysis of a repeat lumbar puncture. Immunophenotyping of cells from the lung biopsy correlated with cells obtained from cerebrospinal fluid. In view of her rapid clinical deterioration, chemotherapy was not pursued, and the patient was transferred to a hospice 3 weeks after admission.

Background

Meningeal carcinomatosis (MC) has been well described in the literature. However, in this patient, we also describe choroidal infiltration of the tumour, and retinal signs of hypopigmentation and mottling, that have not previously been reported. We feel that it is important to highlight MC as a rare but important diagnosis in a patient presenting with unusual neuro-ophthalmological features, with definitive diagnosis made on cytological analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Case presentation

Admission

A 64-year-old female nursery worker, with known rheumatoid arthritis, presented with a 1-month history of a throbbing sensation in both ears, associated with hearing loss on the left and feeling ‘off balance’ while walking. Over the week, preceding admission she had also noticed worsening vision in her right eye, with increasing pain behind the orbit. She had no other significant medical history, but she did admit to a 40-pack-year history of smoking.

On examination, she was alert and orientated, with a Glasgow Coma Score of 15 and no signs of meningism. Cranial nerve examination revealed monocular visual loss with a visual acuity (VA) at distance without correctors (Dsc) of DscOD 6/60 and DscOS 6/12. Visual fields were normal in both eyes, but a relative afferent pupillary defect was noted in the right eye. Further examination, however, revealed a right VI nerve palsy, bilateral downbeat nystagmus on central gaze and left-sided sensorineural hearing loss. On assessment of the gait, impaired heel-to-toe walking was noted, but Romberg’s test was negative. Examination of all other systems, including the peripheral nerves, was normal.

Clinical progression

The patient’s symptoms began to deteriorate within a few days of her admission. Her initial left-sided hearing sensorineural loss became bilateral and profound, and soon communication could only be made by writing notes. On examination, her VA was reduced to DscOD CF (counting fingers) and DscOS 6/24. She was unable to stand unaided, and required a zimmer frame to mobilise. A week later, VA had fallen to DscOD NLP (no light perception) and DscOS CF.

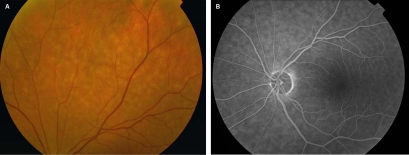

In view of her progressive visual loss, she was examined in the Ophthalmology Department, where in addition to her previous neurological signs, she was also found to have right XI and XII nerve palsies. Fundus angiography showed hypofluorescence, with indocyanine green angiography revealing subtle mid-peripheral mottling and hypopigmentation (figure 1). It was concluded that these signs would be most consistent with an intraocular lymphoma; choroidal and retinal biopsies were recommended for further analysis of this pathology’s nature.

Figure 1.

Retinal images showing abnormal peripheral mottling: (A) fundus photograph and (B) fundus angiography.

Investigations

Routine blood tests were unremarkable. A full autoantibody screen was negative for antinuclear, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic and thyroid peroxidase antibodies, but a mildly elevated rheumatoid factor was reported (39 IU/ml). Other blood tests including thyroid-stimulating hormone, serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and immunoglobulins were all unremarkable. HIV and syphilis assays were negative. An initial chest radiograph was also reported as normal.

An urgent MRI scan showed no evidence of venous sinus thrombosis, but did identify abnormal meningeal enhancement throughout the superior aspects of both cerebral hemispheres and the left mid-parietal region. An area of mild increased signal was noted in the periaqueductal region of the midbrain. Although no space-occupying lesions were seen at the cerebellopontine angle, both vestibulocochlear nerves within the internal auditory meatus appeared bulky and showed enhancement that could represent intracanalicular acoustic neuromas. The radiologists concluded that the MRI findings were most consistent with an acute lesion, possibly inflammatory or neoplastic in nature.

The following day, a lumbar puncture was performed. The CSF was clear and colourless, but the opening pressure was raised at 27 cm H2O. Biochemical analysis revealed a raised level of white cells (43×106/l), CSF protein (5.24 g/l) and lactate (3.7 mmol/l). CSF glucose was normal (3.2 mmol/l) compared to serum glucose (5.6 mmol/l), but there was no evidence of infection on culture of the CSF. Cytological analysis, reported in microbiology, revealed only an excess of small lymphocytes – findings otherwise non-specific for chronic inflammation, viral infection or neoplasia.

A CT neck/chest/abdomen/pelvis was then requested to identify any occult malignancy. Soft tissue masses were found in the right lower lobe and left paravertebral regions (measuring 4.2 and 2.2 cm across the axial plane, respectively) along with subcentimetre left lung nodules. In the abdomen, multiple subcentimetre low attenuation lesions were seen in the liver. The findings were consistent with a possible right lower lobe primary lung neoplasm with metastases, or lymphoma.

A CT-guided lung biopsy of the soft tissue mass demonstrated non-small cell carcinoma with large epithelioid cells. The tumour was squamoid in areas without keratin formation, and subsequent immunohistochemistry confirmed a histopathological diagnosis of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (non-small cell carcinoma).

A repeat lumbar puncture was performed concurrently to obtain CSF for cytological examination. On analysis, the CSF contained occasional highly atypical epithelial cells with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. These appearances, with subsequent supportive immunoprofiling, were consistent with MC resulting from metastatic adenocarcinoma.

Outcome and follow-up

Initially, suspecting an inflammatory or autoimmune aetiology, the patient was given 1 g intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone for 3 days, which provided no clinical benefit. Unfortunately, further investigation and treatment was prevented by the rapid decline in the clinical status of the patient. Within 2 weeks of admission, she had developed bilateral visual and hearing loss, and had become increasingly somnolent and confused. Communication became very difficult, and it was clear that the patient had limited capacity. After discussion with the family, it was decided that further invasive investigation or treatment would not be in the best interest of the patient. Palliative input was sought, and the patient was subsequently transferred to a hospice 3 weeks after admission.

Discussion

The phenomenon of MC was first described by Eberth in 1870.1 Metastatic meningeal involvement is well-recognised in leukaemias and lymphomas, but is rarely seen as the presenting feature of solid tumours. Most cases of MC are associated with breast and lung cancers, although small cell lung carcinomas are a much more common cause than non-small cell carcinomas.2 Diagnosis is confirmed on cytological analysis of CSF or leptomeningeal biopsy, and may also be supported by gadolinium-enhanced MRI. Regardless of the primary tumour, however, most cases of MC remain palliative; median survival with chemotherapy is around 2–6 months.3

Rapid-onset sensorineural hearing loss as the presenting feature of MC is well-recognised in the literature.4 5 Bilateral visual loss is also a recognised complication, due to a variety of mechanisms including optic nerve compression, direct invasion of the optic nerve mesenchyma and microvascular interruption from arachnoid metastases.5 6 However, to our knowledge, the simultaneous presentation of rapidly progressive bilateral visual and hearing loss has only been reported in a few instances.7

In our patient, we also describe previously unreported choroidal findings of mottling and hypopigmentation, suggesting direct tumour invasion of the choroid and subsequent cellular atrophy. The differential diagnosis for visual loss in a patient with known malignancy is cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR). However, in CAR patients, visual loss is usually slowly progressive, with funduscopy revealing attenuated retinal arterioles and retinal pigment epithelium changes.6 CAR patients also have a characteristic electroretinogram (ERG) and autoantibodies to a retinal antigen.6 ERG and CAR antibody testing was not performed in our patient, in view of the clinical presentation, CSF confirmation of MC and MRI findings.

In conclusion, requesting CSF analysis by an experienced cytopathologist may expedite the diagnosis in unusual neurological presentations. The prognosis of MC is poor, hence early recognition and intervention with palliative chemoradiotherapy may delay neurological progression and preserve quality of life.3 We therefore consider it important to make known our experience of MC, as a differential for acute sensorineural hearing loss with multiple cranial nerve palsies, visual loss and choroidal hypopigmentation.

Learning points.

-

▶

MC is a rare but devastating consequence of metastatic disease.

-

▶

It may be the first and only presenting feature of an underlying cancer.

-

▶

Cytological examination of CSF is key to making a timely diagnosis.

-

▶

We also describe a previously unreported association of retinal hypopigmentation and mottling with this condition.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks to Drs Catherine Mummery and Gillian Williams of Northwick Park Hospital and Dr Adnan Tufail of Moorfields Eye Hospital for their valuable input in writing this report.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Eberth CJ. Zur entwicklung des epitheliomas (cholesteatomas) dur pia und der lunge. Virchow’s Arch 1870;49:51–63 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paramez AR, Dixit R, Gupta N, et al. Non-small cell lung carcinoma presenting as carcinomatous meningitis. Lung India 2010;27:158–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhary S, Chamberlain M. Leptomeningeal metastases: current concepts and management guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2005;3:693–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchese MR, La Greca C, Conti G, et al. Sudden onset sensorineural hearing loss caused by meningeal carcinomatosis secondary to occult malignancy: report of two cases. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010;37:515–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeAngelis LM, Boutros D. Leptomeningeal metastasis. Cancer Invest 2005;23:145–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy J, Marcus M, Shelef I, et al. Acute bilateral blindness in meningeal carcinomatosis. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:206–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kountourakis P, Ardavanis A. Visual and hearing loss due to colorectal meningeal carcinomatosis: a case-based review. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2010;8:567–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]