Abstract

GABAA receptors have been shown to modulate dopaminergic output from the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) in studies of both natural and drug rewards, including alcohol. Ro15-4513, the imidazobenzodiazepine derivative and allosteric modulator at the GABAA receptor, reliably antagonizes the behavioral effects of alcohol. Various models of alcohol consumption show a decrease in consummatory behaviors, specific to ethanol, following acute administration of the drug. In the present study, Ro15-4513 was systemically administered, or microinjected into the anterior or posterior VTA, to explore the role of GABAA receptors at this region in modulating the high pattern of alcohol consumption by C57BL/6J inbred mice in the Drinking in the Dark (DID) model. Animals had 2 hour access to ethanol for 6 days prior to drug manipulations. Immediately before the seventh day of access, mice were systemically (I.P.) or site-specifically administered Ro15-4513. Systemic Ro15-4513 (at 10mg/kg) decreased binge-like ethanol intake in the DID paradigm. Additionally, there was a stepwise decrease in consumption following Ro15-4513 microinjection into the posterior VTA, with the highest dose significantly decreasing ethanol intake. There was no effect found following microinjection into the anterior VTA, nor was there an effect of systemic or intra-posterior VTA Ro15-4513 on consumption of a 5% sucrose solution or water. The present findings support a role for Ro15-4513 sensitive VTA-GABAA receptors in modulating binge-like ethanol consumption. Moreover, the work here adds to the growing body of literature suggesting regional heterogeneity in the VTA.

Keywords: GABAA, ventral tegmental area, VTA, Ro15-4513, C57BL/6J, mouse, alcohol, extrasynaptic receptors, Drinking-in-the-Dark

Introduction

Binge alcohol consumption is an important behavioral marker of many alcohol use disorders. Pharmacologically defined as alcohol intake producing a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 80mg/dL or greater [1], this level of drinking results in behavioral intoxication and presumably activates the neurobiological systems involved in the reinforcing properties of alcohol. Specifically, given the supported role of receptor systems localized to the mesocorticolimbic pathway in regulating reinforcement [2–6], modulation of said pathways should alter patterns of binge drinking. Due to ethical constraints, animal models have been vital in our efforts to explore the role of various receptor systems in mediating ethanol related behaviors. In particular, the drinking in the dark (DID) limited access paradigm allows us to model binge-ethanol intake in various inbred mouse strains [7, 8]. We have recently begun to use this DID procedure to investigate the role of receptor systems in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), that modulate activity along the mesocorticolimbic reward pathway, in mediating binge intake of ethanol.

The VTA contains GABAergic neurons that both locally and distally inhibit activity in the reward pathway [9, 10]. GABAA receptors, in particular, have been shown to mediate tonic inhibition of this dopaminergic pathway [11–13]. For example, David and colleagues [14] showed that mice would successfully self-administer bicuculline (GABAA antagonist) into the VTA and that this self-administration could be extinguished by pretreatment with sulpiride, a dopamine receptor antagonist.

GABAA receptors are interesting pharmacological targets because of their structural diversity. This pentameric ionophore complex may be composed of multiple protein classes, many of which exist as varying isoforms. The subunit composition of the GABAA receptor complex confers unique pharmacological properties to the receptor subtypes [15]. For example, various α subunit isoforms have been associated with benzodiazepine insensitivity. Interestingly, it is posited that Ro15-4513, a compound repeatedly shown to antagonize the behavioral and physiological effects of alcohol, may be exerting its effects by competing with alcohol for respective binding sites on these benzodiazepine-insensitive receptors [16, 17].

Ro15-4513 has long been considered an antagonist of alcohol’s actions at the GABAA receptor complex. Electrophysiological evidence in synaptoneurosome preparations [18, 19] support an attenuation of ethanol’s potentiation of GABAA mediated chloride flux, following Ro15-4513 application. Behaviorally, the drug has been shown to block the sedative-hypnotic, anxiolytic and intoxicating effects of ethanol in various rodent models [20–25]. Ro15–4513 has also successfully attenuated self-administration of ethanol in various paradigms [26–28]. The consistent attenuation of alcohol responding induced by Ro15-4513 pretreatment has been interpreted as a reduction in the motivational properties of the drug [29]. However, experimental evidence does not necessarily support this interpretation. For example, Risinger and colleagues [30] found that Ro15-4513 did not alter the induction of a conditioned response to an environment paired with ethanol administration. Site-specific administration of the drug, to reward relevant areas like the VTA, may clarify its mechanism for reducing ethanol responding.

Significant evidence to date suggests anatomical and functional diversity in the VTA regarding its role in mediating reinforcement. Anatomically, the anterior and posterior regions of the VTA have distinct projections (most efferents to the medial prefrontal cortex from the VTA, for example, originate from the posterior zones; [31]) as well as varied levels of innervations at other terminal sites[32]. This heterogeneity has been shown to extend to functional responses, especially in terms of the GABAergic system and its role in mediating the effects of ethanol. Work from our laboratory found bidirectional effects of modulating the metabotropic GABA receptor system on ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation [33]. In this study, anterior VTA administration of the GABAB agonist baclofen, decreased ethanol-induced hyperlocomotion; the opposite effect was found following posterior-VTA administered baclofen. This functional heterogeneity, importantly, extended to manipulation of binge-like ethanol intake in the Drinking in the Dark model [34]. This diversity has been demonstrated for other receptor systems [35, 36].

The ionotropic GABA receptor complex has also been shown to have a unique relationship with the anterior and posterior VTA regions. Ikemoto and colleagues [37] showed that rats in an operant self administration paradigm would only self-administer GABAA antagonists (like picrotoxin) into the anterior VTA. Furthermore, the same laboratory was able to establish that rats in the same paradigm would only self-administer GABAA agonists (like muscimol and ethanol) into the posterior VTA [38, 39]. The possibility remains that the heterogeneity of VTA responsivity to GABAA ligands is also related to differences in GABAA receptor subtype across the anterior and posterior zones of the structure.

The present study sought to investigate the role of the “alcohol antagonist” Ro15-4513 in mediating binge-like intake in the alcohol preferring C57BL/6J inbred mouse strain, using the DID paradigm. Further, we wished to explore the role of the anterior and posterior VTA in mediating the effects of this drug on binge intake. Given the previously discussed effects of Ro15-4513 on operant self-administration of ethanol, we hypothesize that Ro15-4513 will decrease binge like ethanol intake following systemic administration. In addition, given the findings from our lab and others described earlier, we hypothesize that site specific administration of Ro15-4513 will produce bidirectional effects on binge-like ethanol intake. Specifically, we predict an increase in binge consumption following posterior-VTA administration and a decrease in binge consumption following anterior-VTA infusion of Ro15-4513.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Subjects were female C57BL/6J inbred mice bred and maintained at Binghamton University (Experiment 1a and 1b) or Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) School of Science (Experiment 1c and Experiment 2a through 2c). Mice were 70–100 days old at the start of each experiment. Animals were individually housed in standard shoebox cages and habituated to a 12 hour reverse light/dark schedule for at least 7 days. The temperature of the colony rooms was maintained at 21 ± 1 degrees Celsius. Food was available ad libitum except during stereotaxic surgery. Water was available ad libitum except during stereotaxic surgery (for all animals in Experiment 2) and when ethanol was made available as per DID protocol (see below). Procedures for Experiments 1a and 1b were approved by the Binghamton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Procedures for Experiments 1c and all of Experiment 2 were approved by the IUPUI School of Science IACUC. Procedures in all experiments conformed to NIH Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research [40].

Drugs and Drinking Solutions

Ethanol (190 proof) was obtained from Pharmco, Inc (Brookfield, CT). Ethanol drinking solutions (20% v/v) were made with tap water. Sucrose drinking solution (5% w/v) was prepared by dissolving sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in tap water. Ro15-4513 15-4513 was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The drug and final drug solutions were stored in opaque plastic bottles or foil wrapped glass vials. For systemic administration, the drug was suspended in Tween-80 and diluted with sterile physiological saline. Vehicle administered in systemic experiments consisted of physiological saline and Tween-80. For microinjections, the drug was solubilized using dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and serially diluted to final concentrations. This process reduced the final concentration of DMSO in the drug solutions to 0.01–0.1%. Vehicle administered in the microinjection experiment was a solution of 0.1% DMSO in physiological saline.

Drinking in the Dark

Beginning three hours following lights out, water bottles were removed from each animal and replaced with modified sipper tubes made from 10mL graduated cylinders fitted with double ball bearing sippers (Ancare, Belmore, NY). Modified drinking tubes contained ethanol (Experiment 1a and 2a), water (Experiment 1b and 2b) or a 5% (w/v) sucrose solution (Experiment 1c and 2c). Animals had access to drinking tubes for 2 hours; there was no access to regular water bottles during this limited access procedure. Fluid intake was recorded as the change in fluid level along the modified drinking tube graduations.

Microneurosurgery

Guide cannulae, stylets and tubing to make injection cannulae were obtained from Small Parts Inc. (Miami Lakes, FL). Guide cannulae were made of 25-gauge stainless steel tubing, pre-cut to 15.5mm. Stainless steel wire (0.0095 inch) was used to make stylets, which were inserted inside the guide cannulae to prevent obstruction. The guide cannulae were implanted 3mm above the VTA by stereotaxic surgery (Model 1900; David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) as previously described [33, 34]. Mice were first anesthetized using a ketamine/xylazine cocktail (containing 100mg of Ketamine and 10mg of xylazine in 10mL saline), administered intraperitoneally in a volume of 0.1mL/10g of mouse weight. The animal’s dorsal scalp was shaved and a midline incision was made, revealing the skull from bregma to lambda (about 3 mm wide). The skull was cleaned with surgical scrub and sterilized using 100% ethanol (Pharmco Inc, Brookfield, CT). The 1997 edition of Franklin and Paxinos’ Mouse Brain Atlas was used for coordinates. The anterior-VTA coordinates (from bregma: caudal 3.16mm, lateral 0.5mm, and ventral 2.0mm) and posterior-VTA coordinates (from bregma: caudal 3.64mm, lateral 0.5mm, and ventral 2.0mm) were adjusted for each mouse. To accomplish this, the published distance between bregma and lambda in this species (4.21mm) was divided by the distance between bregma and lambda measured for each individual mouse. This quotient was then multiplied to each anterior or posterior coordinate listed above. Bilateral craniotomy holes were drilled at these individualized coordinates for placement of the guide cannulae. A third hole was drilled for an anchor screw (this third hole was enlarged using an 1/8 inch hand-held drill; Small Parts, Miami Lakes, FL, USA). Guide cannulae were lowered into position (2mm above VTA region of interest) and durelon carboxylate cement (Norristown, PA, USA) was applied to the exposed cranium to hold the assembly in place. Animals remained in the stereotaxic apparatus until cement dried. Following surgery, mice were subcutaneously administered the anti-inflammatory drug carprofen (Rimadyl, 5mg/kg, Pfizer Animal Health, USA), and the analgesic drug buprenorphine (Buprenex, 0.06mg/kg, Reckitt and Coleman Pharmaceuticals, Richmond, VA) and were monitored for healthy recovery.

Blood Ethanol Concentration

Immediately following the 2-hour ethanol access on the final day of the experiment (day of drug manipulation), animals were removed from the room (in order to prevent disruption to animals still consuming) and retro-orbital sinus bloods (50 μL) were collected in heparinized microcapillary tubes (Micro-Hematocrit Capillary Tube; inner diameter of 1.1–1.2 mm and wall diameter of 0.2 ± 0.02 mm,; FisherScientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Blood samples were centrifuged and plasma supernatant was stored at −20°C. Samples were later analyzed using an Analox Alcohol Analyzer (Analox Instruments, Lunenburg, MA) and blood ethanol concentrations (BEC) were recorded as mg/dL.

EXPERIMENT 1: Effect of systemic Ro 15-4513 on Binge-like Ethanol intake using DID procedures

1a–c. Effect of Systemic Ro 15-4513 on a)Ethanol, b) Water, or c)Sucrose Intake

Three hours following lights out, animals received access to ethanol (20 % v/v, unsweetened), water, or a sucrose solution(5% w/v), as per the Drinking in Dark procedure detailed above, for 7 consecutive days. Immediately prior to access on the seventh day, animals were removed from the cage and administered vehicle or Ro15-4513 (at 2.5, 5 or 10 mg/kg).

Statistical Analysis

Limited access fluid intake (ethanol, water or sugar water) across the six days prior to drug administration was analyzed separately for each solution, using a Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM-ANOVA). Intakes following drug challenge were analyzed separately for each fluid using a One-Way ANOVA (between-subjects), with drug dose (0, 2.5 5 and 10 mg/kg) as the independent factor. Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to explore differences across drug doses when the ANOVA revealed significant main effect of this factor. Criterion for statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

EXPERIMENT 2: Effect of Intra-VTA Ro 15-4513 on Binge-like Ethanol intake using DID procedures

2a – c. Effect of Site Specific Ro 15-4513 on a) Ethanol, b) Water, or c) Sucrose Intake

Animals were allowed 7 days of recovery before microinjection of Ro15-4513. The day following surgical implantation of the guide cannulae (see above), mice were handled for 30 seconds and stylets were adjusted. Handling occurred daily in order to habituate animals to the level of restraint used during the microinjection process. Access to alcohol was initiated on the second day following surgery. Immediately prior to fluid access (as per DID procedures) on this first drinking day, mice were handled as described above. This 30 second handling procedure preceded drinking on days 1 and 2. The introduction to the DID procedure was necessary in order to establish stable, binge-like ethanol intakes prior to manipulation by drug microinjection. The restraint procedure was increased to 60 seconds on days 3 and 4 of the DID limited access procedure. For the final two days preceding Ro15-4513 microinjection (days 5 and 6 of fluid access), mice were handled for 90 seconds. These two handling sessions were preceded by mock microinjections. During the mock microinjection procedure, injection cannulae were inserted into the guide cannulae (these injection cannulae extended only 2mm past the guide cannulae into the brain, ending 1mm above the VTA). On day 7 of fluid access, animals received an intra-VTA microinjection (injection cannulae extended 3 mm below the guide cannulae) of Ro15-4513 or vehicle immediately prior to access to ethanol or sucrose. Following ethanol access, retro-orbital sinus blood samples were collected for determination of blood ethanol concentration (BEC).

Intra-VTA Microinjections

Injection cannulae were made from two sections of stainless steel tubing: a 30mm section of 32-gauge tubing was inserted into a 30mm section of 25-gauge tubing so that 18mm extended (Small Parts Inc., Miami Lakes, FL). Super glue was used to hold the sections together (Krazy Glue, Columbus, OH).

Two 50cm segments of PE-20 tubing were each attached to the injection cannulae and loaded with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or Ro15-4513. The alternate ends of tubing were fitted over two 10-μl Hamilton glass syringes (Hamilton Co., Reno, NV, USA) filled with distilled water. These syringes were fitted to a Cole-Parmer (74900-Series) dual infusion pump. During the microinjection procedure, the animal was restrained and the injection cannulae were slowly inserted and held in place. The tips of the injection cannulae extended 3mm below the end of the guide cannulae to reach the anterior or posterior VTA. Ro15-4513 or vehicle (200 nl per side) was microinjected at a rate of 382 nl/min. The microinjection took approximately 30 seconds, and the injection cannulae remained in place for an additional 60 seconds following the end of the microinjection in order to ensure diffusion of the administered fluid away from the injection cannulae. Each injection cannula was removed slowly, to prevent the fluid from being drawn back up through the guide cannulae.

Histology

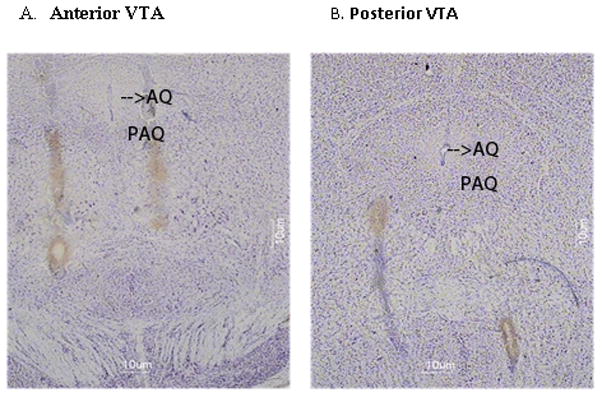

Immediately following the final day of behavioral testing, animals were anesthetized using isoflurane and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Brains were removed and flash-frozen using ice-cold isopentane (−30°C; chilled using dry ice). Forty-micron coronal slices were cut on a CM 3050S Leica cryostat (Walldorf, Germany) and thaw-mounted on microslides (25 × 75 × 1 mm; VWR, West Chester, PA). Brain slices were thionin stained (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and cover slipped (microcover glass 24 × 60; VWR, West Chester, PA) for cannulae placement inspection. Photomicrographs of representative anterior and posterior VTA microinjection placement can be seen in Fig 1.

Figure 1. Histological verification of cannulae placement.

Representative microinjection tracks into the anterior (A) or posterior (B)590 VTA.

Statistical Analysis

Only animals with correctly placed injection cannulae were included in statistical analysis of data (Statistica release 7; StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK). This resulted in the removal of 2–3 animals per group (hit rate= 73%). An additional seven mice were removed from the study as their skull caps detached during the handling process (n=4), a guide cannulae became displaced (n=1) or was clogged (n=2).

The first 6 days of ethanol, water or sucrose consumption were separately analyzed using a two-way mixed ANOVA, with day as the within subjects factor and VTA region (anterior or posterior) as the between subjects factor. Consumption and BECs (when applicable) following microinjection on day 7 of fluid access were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, with VTA region and drug concentration as the between subject factors. Tukey’s post-hoc tests were carried out where appropriate. Results were considered significant at p <0.05.

Results

EXPERIMENT 1: Effect of systemic Ro 15-4513 on Binge-like Ethanol intake using DID procedures

1a–c. Effect of Systemic Ro 15-4513 on a)Ethanol, b) Water, or c)Sucrose Intake

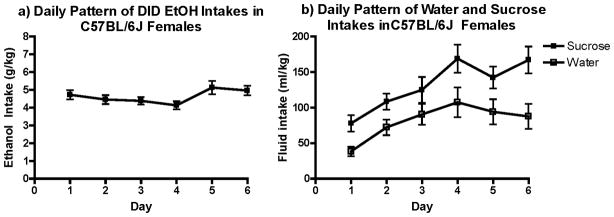

Average ethanol, water and sucrose intake across the 6 days prior to drug administration are respectively illustrated in Figure 2a, b and c. Ethanol consumption remained stable across the days, with mice consuming an average of 4.96 g/kg the day prior to drug challenge. Water intake showed a more variable pattern, with RM-ANOVA revealing a main effect of day [F(5, 105)=6.1, p<0.001; Fig. 2b]. Mice also increased their sucrose intake (Fig. 2b) over time, as the statistical analysis revealed a main effect of day [F(1, 140)= 13.3, p<0.000].

Figure 2. Pattern of intake before drug challenge.

a) Ethanol intake was fairly stable over days in the DID paradigm. b) Water and Sucrose intakes were less stable, as both showed a significant effect of day (p’s <0.001).

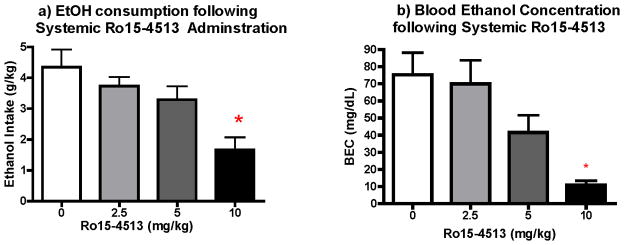

Immediately before ethanol, water or sucrose access on the seventh day, animals were administered Ro15-4513 (2.5, 5 or 10mg/kg) or vehicle. Results of this pharmacological manipulation on intake can be seen in Fig. 3a, Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b, respectively. Separate One-Way ANOVAs were performed for each drinking solution (drug dose as factor). This analysis revealed a significant effect of dose [F (3, 20)=5.36, p<0.01] on ethanol consumed during the 2-hour access period. Tukey’s post hoc revealed a significant attenuation in ethanol intake in animals administered the highest dose (10mg/kg) of Ro 15-4513 (p<0.01).

Figure 3. Effect of Ro15-4513 on Ethanol intake and Blood Ethanol Concentration.

a) Ro15-4513 administration significantly decreased binge-like ethanol consumption (n=6–7; p<0.). b) Ro 15-4513 administration significantly decreased BEC at the highest dose group (n=5–7).

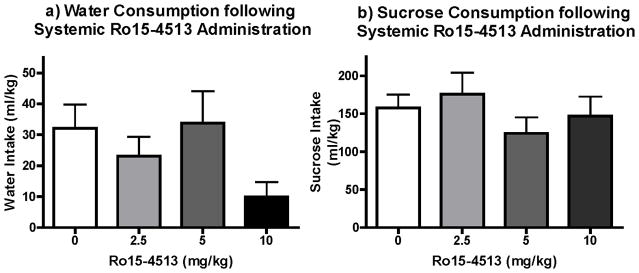

Figure 4. Effect of Ro15-4513 on Water and Sucrose Intake.

a) Ro 15-4513 did not have a statistically significant effect on Water intake (n=6), but non-specific trends seem apparent. b) There was no effect of the drug on sucrose intake (n=7).

Analysis of blood ethanol concentration (Figure 3b) reflected the effect of Ro15-4513 dose on ethanol intake [F(3, 20)= 9.28, p<0.01], driven specifically by the significant decrease in the highest dose group (p<0.01). Though ethanol intake was not significantly attenuated by the 5mg/kg dose of Ro15-4513, a trend is notable in the analysis of BECs following this dose.

Statistical analysis of water intakes did not reveal a significant effect of dose. However, there was a notable change in water consumption at the lowest and highest doses, which made interpreting the specificity of the drug effects to ethanol consumption difficult (Fig. 4a). Therefore, we explored the effects of Ro15-4513 on sucrose (5%, w/v) intake and found no support for an effect of the drug at any of the doses administered (Fig. 4b).

EXPERIMENT 2: Effect of Intra-VTA Ro 15-4513 on Binge-like Ethanol intake using DID procedures

2a – c. Effect of Site Specific Ro 15-4513 on a) Ethanol, b) Water, or c) Sucrose Intake

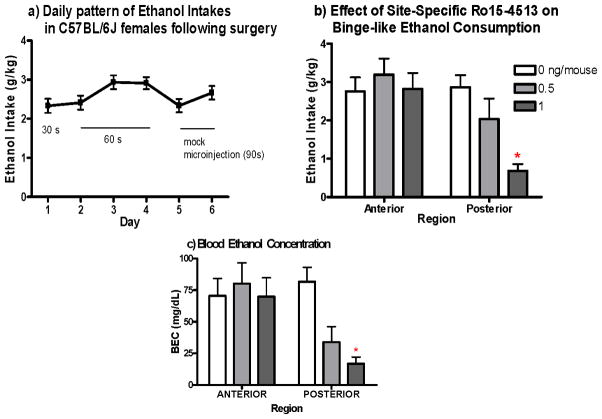

Ethanol intake was initiated two days following surgical implantation of guide cannulae. Statistical analysis (RM-ANOVA, with day as within subject factor) revealed a significant effect of day [F(5, 250)=3.97, p<0.01; Fig. 5a]. Tukey’s post hoc revealed that the increase in ethanol intake across these habituation days peaked at days 3 through 4 of ethanol access (average intake was 2.9g/kg for both days), and decreased on the fifth day of access (the first day of mock-microinjections).

Figure 5. Effect of intra-anterior and -posterior VTA Ro15-4513 on binge-like ethanol consumption.

a) ) Mice increased consumption across habituation days, with intakes stabilizing consumption by third day of alcohol access. b) Ro 15-4513 significantly decreased ethanol intake at the highest dose in the posterior VTA, but had no effect at any dose in the anterior VTA (n = 7–11). c) BEC’s reflects this site specific attenuation of binge consumption (n=5–8). *p<0.01

Immediately prior to ethanol on the seventh day of access, animals were microinjected with Ro15-4513 at 0.5 and 1ng/mouse or vehicle.

Two-Way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between drug manipulation and VTA region [F(2,48)= 6.055, p<0.05; Fig. 5b]. This effect was found to be driven by a significant attenuation of drinking following superfusion of the posterior-VTA with 1ng/mouse of Ro 15-4513 (p<0.01; Tukey’s post hoc). There was no change in consumption following administration of any dose of Ro15-4513 into the anterior VTA.

Results from BEC data analysis were consistent with the intake data, showing an interaction of dose and region [F(2,42)=3.38, p<0.05; Fig. 5c] and significant decrease in BEC only at the 1ng/mouse dose administered in the posterior-VTA (p<0.01). Analysis of post-DID BEC in cannulated animals microinjected with vehicle supports the notion that C57BL/6J mice continue to exhibit binge-like ethanol consumption following the stressful procedures associated with site-specific manipulation

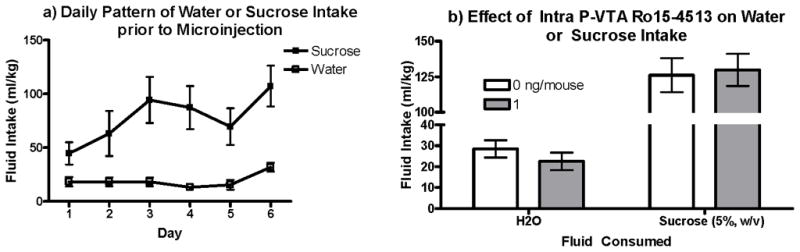

Two days following surgical implantation of guide cannulae into the posterior-VTA, mice were given 2 hour access to water or a sucrose solution (5%, w/v). There was a significant change in both water [F(5,55)=508.53, p<0.001] and sucrose[F(5,50= 3.12, p<0.05] intake across the six days of access (Fig. 6a). This effect of day appears to be driven by an increase in consumption on the final day of mock-microinjections, which increased significantly from the prior day for mice consuming sucrose (p<0.05) and the prior two days for mice consuming water (p’s <0.05). Statistical analyses (t-tests) did not reveal any difference in the amount of water or sucrose consumed on the seventh day of access, following saline or 1ng/mouse of Ro15-4513 microinjection into the posterior VTA (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6. Effect of posterior-VTA Ro15-4513 administration on water and sucrose intake.

Ro15-4513 infused into the posterior VTA did not statistically affect the amount of a) water or b) sucrose consumed by the mice (n=5–6).

Discussion

The present series of experiments support a role for Ro15-4513-sensitive GABAA receptors in the modulation of binge-like ethanol intake, as systemic administration of the drug attenuated ethanol intake in the Drinking in the Dark (DID) paradigm. Our results also provide evidence for a role of intra-VTA GABAA receptors in mediating this attenuation. Moreover, the unique effects of intra-anterior versus posterior Ro15-4513 on binge-like intake adds to the growing body of evidence supporting functional and neurochemical heterogeneity in the VTA, with modulation of GABAergic receptors in the posterior VTA attenuating binge-like ethanol intake.

Our findings that systemic administration of Ro15-4513 decreased ethanol intake in a self-administration paradigm are consistent with previous investigations of the effects of this atypical benzodiazepine on ethanol self-administration [26–28]. It seems counterintuitive that decreases in ethanol self-administration would be produced from a drug shown to antagonize the motor incoordinating and sedating effects of ethanol, as these effects are often interpreted as rate-limiting factors in continued ethanol consumption. However, Ro 15-4513 is not a classic antagonist, but rather a partial inverse agonist, with intrinsic effects at the GABAA receptor complex. Functionally, the drug has been shown to reduce exploratory behavior in rodents [41]. Therefore, one explanation of the reduction in ethanol drinking seen here is that pretreatment with Ro15-4513 prior to ethanol presentation in our limited-access paradigm, increased anxiety, reducing approach behaviors towards the sipper tube, and thus ethanol drinking. However, this possibility can be ruled out by the fact that the anxiogenic effects of Ro15-4513 are noted at doses as low as 3mg/kg [42]; a dose greater than this anxiogenic dose (5mg/kg) failed to significantly reduce ethanol intake in our limited access paradigm (Fig. 3A). An alternative explanation for the results is that Ro15-4513 is binding to the very same GABAA receptors that alcohol usually would be binding to, in a binge session, to produce some of its physiological effects. Wallner and colleagues [17] support this idea of competitive relationship between Ro15-4513 and ethanol, with the compound binding to its site on the GABAA receptor complex and “blocking” a proposed ethanol-binding site. In blocking ethanol’s ability to bind to its receptor, Ro15-4513 therefore, could be decreasing the reinforcing properties of ethanol consumed in our DID paradigm. Caution should be taken, however, given the complex relationship between Ro15-4513 and alcohol demonstrated by the same team of researchers, who suggest that alcohol may have an ability to inhibit Ro15-4513 binding as well [16]. Further caution must be taken in interpreting changes in intake with changes in the reinforcing salience of a stimulus, though evidence does suggest a positive relationship between the two, with respect to ethanol responding [44].

Although the surgery and handling procedures necessary in the site-specific experiment reduced the ethanol intakes achieved (as compared to the systemic study), the consumption can still be considered binge-like as blood ethanol concentration in control animals (microinjected vehicle) approached 80mg/dL (Fig. 5b). Therefore, our results suggest that microinjection of Ro15-4513 into the posterior VTA decreased binge-like consumption, when compared to microinjection of vehicle into the same region. The functional heterogeneity explored in the present work was first examined by Arnt and Scheel-Kruger. In this 1979 work, the authors found unique effects of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and antagonists when microinjected into what they called the rostral and caudal regions of the VTA. Specifically they saw a locomotor activating effect following GABAA antagonists into the rostral (or anterior) VTA and a locomotor depressant effect of agonists administered into the caudal (or posterior) VTA. This functional heterogeneity was later shown to extend to consummatory and operant self administration paradigms, with animals self administering GABAA antagonists into the posterior VTA and agonists into the anterior-VTA [37–39]. Given this body of work, we hypothesized that Ro15-4513 would bidirectionally alter ethanol intake. Specifically, we predicted an increase in ethanol consumption following superfusion of Ro15-4513 into the posterior VTA and a decrease in ethanol intake following anterior VTA application of the drug. Indeed, Nowak and colleagues [45] were able to attenuate ethanol intake by blocking GABAA receptors (using picrotoxin) in the anterior VTA of female P rats (line selected for alcohol preference). We, however, found no effect of intra-anterior VTA Ro15-4513 on ethanol intake in B6 female mice. Furthermore, the decrease in binge-like ethanol intake following intra-posterior Ro15-4513 was the opposite of what was hypothesized.

One possible explanation of the results concerns Ro15-4513’s classification as an “atypical” benzodiazepine and the selectivity of this drug for various GABAA receptor subtypes. As noted in the introduction, GABAA receptors are heteropentameric structures comprised of various protein classes and isoforms. The subunit composition of these receptors confers unique pharmacological characteristics. An important change in GABAA receptor pharmacology related to subunit composition is the shift in benzodiazepine sensitivity noted across α protein isoforms. A change in the histidine residue of the benzodiazepine binding pocket of α1, α2, α3, and α5 subunits to arginine in α4 and α6 subunits, has been proposed to abolish benzodiazepine sensitivity in GABAA receptor subtypes containing the latter two isoforms [46]. Although these benzodiazepine insensitive subunits are usually co-expressed with the δ subunit protein, they have been expressed with γ2 subunit proteins in recombinant systems [47]. Moreover, Ro15-4513 has been shown to have opposite effects on benzodiazepine insensitive GABAA receptors, given their expression of δ or γ2 subunit proteins. Specifically, while the drug has been demonstrated to have inverse agonist properties at δ expressing benzodiazepine insensitive GABAA receptors, Knoflach and colleagues [47] showed that the compound may actually potentiate GABA evoked responses in recombinant γ2 expressing benzodiazepine-insensitive receptors. In a behavioral assessment of this position, Crestani and colleagues [48] found that Ro15-4513 depressed locomotion in a line of transgenic mice designed to show increased levels of benzodiazepine-insensitive receptors (these mice expressed the histidine to arginine point mutation that occurs naturally at α4 and α6 subunits, at their α1 isoforms), whereas the drug increased locomotion in the wildtype 129/SvJ. Our present findings, therefore, may be explained by Ro15-4513 acting primarily as an agonist at α4/γ2 and α6/γ2 containing GABAA receptors in the posterior-VTA.

Given the previously discussed heterogeneity of anterior and posterior VTA and proposed roles of GABAA receptors across the region, potentiation of GABAA receptor activity in the posterior VTA might result in disinhibition of VTA-dopamine neurons. This is the same effect suggested to result from antagonism of GABAA receptors in the anterior VTA (Nowak et al. 1998). An integral step in clarifying our results, to this end, would be characterization of the populations of GABAA receptor subtypes across the anterior versus posterior VTA. While this work has been completed for areas like the thalamus (where 60–70% of α4 subunits were shown to coprecipitate with δ subunit proteins; [49]), the distribution of these subunits across the VTA in C57BL/6J mice has not been explored. Alternatively, we can attempt to modulate binge-like ethanol intake following posterior-VTA administration of a full agonist specifically selective (at appropriate concentrations) for δ subunit containing benzodiazepine-insensitive receptors, like gaboxadol (THIP).

Many of the effects of drugs of abuse, including ethanol, on the mesocorticolimbic reward pathway are interpreted as modulation (either direct or indirect) of dopamine activity. Indeed, dopamine concentration in the mesocorticolimbic pathway is positively associated with the administration/presentation of rewards or cues conditioned with reward access [5, 54, 55]. There is, however, evidence for a non-dopaminergic reward pathway originating from the VTA [56]. This dopamine-independent motivational system is proposed to consist mainly of GABAergic efferents terminating in cortical regions [57]. Moreover, Laviolette and van der Kooy [57] show that GABAA antagonists have a unique relationship with this non-dopaminergic reward pathway. As noted earlier, posterior VTA is suggested to have stronger projections to frontal cortical regions (like the medial prefrontal cortex). Therefore, the possibility remains that our results are reflective of regional heterogeneity in the VTA with respect to this dopamine-independent motivational system.

In conclusion, the present experiments support a role for GABAA receptors in mediating the binge-like ethanol consumption produced using the Drinking in the Dark paradigm in C57BL/6J female mice. Moreover, our findings of regional heterogeneity in the VTA with respect to modulating binge-like ethanol intake concur with data suggesting functional heterogeneity across the anterior and posterior VTA in regulating ethanol reinforcement. Future work using subunit selective compounds is needed in order to clarify the role of GABAA subtype diversity in mediating this heterogeneity and binge- like ethanol consumption.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.NIAAA National Advisory Council NIAAA Council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang A, George MA, Randall JA, Gonzales RA. Ethanol Increases Extracellular Dopamine Concentration in the Ventral Striatum in C57BL/6 Mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1083–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075825.14331.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimoto K, McBride W, Lumeng L, Li T. Alcohol stimulates the release of dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens. Alcohol. 1992;9:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(92)90004-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thielen R, Engleman E, Rodd Z, Murphy J, Lumeng L, Li T, et al. Ethanol drinking and deprivation alter dopaminergic and serotonergic function in the nucleus accumbens of alcohol-preferring rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004;309:216. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boileau I, Assaad JM, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C, Leyton M, Diksic M, et al. Alcohol promotes dopamine release in the human nucleus accumbens. Synapse. 2003;49:226–31. doi: 10.1002/syn.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodie MS, Appel SB. Dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice differ in sensitivity to ethanol excitation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes JS, Ford MM, Yu CH, Brown LL, Finn DA, Garland T, Jr, et al. Mouse inbred strain differences in ethanol drinking to intoxication. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore EM, Serio KM, Goldfarb KJ, Stepanovska S, Linsenbardt DN, Boehm SL., 2nd GABAergic modulation of binge-like ethanol intake in C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;88:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Churchill L, Dilts R, Kalivas P. Autoradiographic localization of -aminobutyric acid A receptors within the ventral tegmental area. Neurochemical research. 1992;17:101–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00966870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westerink B, Enrico P, Feimann J, De Vries J. The pharmacology of mesocortical dopamine neurons: a dual-probe microdialysis study in the ventral tegmental area and prefrontal cortex of the rat brain. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;285:143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruen R, Friedhoff A, Coale A, Moghaddam B. Tonic inhibition of striatal dopamine transmission: effects of benzodiazepine and GABAA receptor antagonists on extracellular dopamine levels. Brain Research. 1992;599:51–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90851-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolders I, De Klippel N, Sarre S, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. Tonic GABA-ergic modulation of striatal dopamine release studied by in vivo microdialysis in the freely moving rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;284:83–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00369-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smolders I, Bogaert L, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. Muscarinic modulation of striatal dopamine, glutamate, and GABA release, as measured with in vivo microdialysis. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1942–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68051942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.David V, Durkin TP, Cazala P. Self-administration of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline into the ventral tegmental area in mice: dependence on D2 dopaminergic mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130:85–90. doi: 10.1007/s002130050214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABA A receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanchar H, Chutsrinopkun P, Meera P, Supavilai P, Sieghart W, Wallner M, et al. Ethanol potently and competitively inhibits binding of the alcohol antagonist Ro15-4513 to 4/6 3 GABAA receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:8546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509903103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Low-dose alcohol actions on alpha4beta3delta GABAA receptors are reversed by the behavioral alcohol antagonist Ro15-4513. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8540–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzdak PD, Schwartz RD, Skolnick P, Paul SM. Ethanol stimulates gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-mediated chloride transport in rat brain synaptoneurosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4071–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glowa JR, Crawley J, Suzdak PD, Paul SM. Ethanol and the GABA receptor complex: Studies with the partial inverse benzodiazepine receptor agonist Ro 15-4513 15-4513. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1988;31:767–72. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le A, Mana M, Pham T, Khanna J, Kalant H. Effects of Ro 15-4513 15-4513 on the motor impairment and hypnotic effects of ethanol and pentobarbital. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;159:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman P, Tabakoff B, Szabo G, Suzdak P, Paul S. Effect of an imidazobenzodiazepine, Ro15-4513, on the incoordination and hypothermia produced by ethanol and pentobarbital. Life sciences. 1987;41:611–20. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker H. Effects of the imidazobenzodiazepine RO15-4513 on the stimulant and depressant actions of ethanol on spontaneous locomotor activity. Life sciences. 1988;43:643–50. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzdak P, Paul S, Crawley J. Effects of Ro15-4513 and other benzodiazepine receptor inverse agonists on alcohol-induced intoxication in the rat. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1988;245:880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzdak P, Schwartz R, Skolnick P, Paul S. Ethanol stimulates gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-mediated chloride transport in rat brain synaptoneurosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1986;83:4071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dar M. Modulation of ethanol-induced motor incoordination by mouse striatal A1 adenosinergic receptor. Brain research bulletin. 2001;55:513–20. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samson HH, Tolliver GA, Pfeffer AO, Sadeghi KG, Mills FG. Oral ethanol reinforcement in the rat: Effect of the partial inverse benzodiazepine agonist RO15-4513. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1987;27:517–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samson HH, Haraguchi M, Tolliver GA, Sadeghi KG. Antagonism of ethanol-reinforced behavior by the benzodiazepine inverse agonists Ro15-4513 and FG 7142: relation to sucrose reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;33:601–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.June HL, Hughes RW, Spuriock HL, Lewis MJ, Building CBP. Ethanol self-administration in freely feeding and drinking rats: effects of Ro15-4513 alone, and in combination with Ro15-1788 (flumazenil) Psychopharmacology. 1994:332–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02245074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rassnick S, D’Amico E, Riley E, Koob GF. GABA antagonist and benzodiazepine partial inverse agonist reduce motivated responding for ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Risinger FO, Malott DH, Riley AL, Cunningham CL. Effect of Ro 15-4513 15-4513 on ethanol-induced conditioned place preference. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90644-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oades RD, Halliday GM. Ventral tegmental (A10) system: neurobiology. 1. Anatomy and connectivity. Brain Res. 1987;434:117–65. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(87)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikemoto S. Dopamine reward circuitry: two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56:27–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boehm S. Ventral tegmental area region governs GABAB receptor modulation of ethanol-stimulated activity in mice. Neuroscience. 2002;115:185–200. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00378-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore EM, Boehm SL., 2nd Site-specific microinjection of baclofen into the anterior ventral tegmental area reduces binge-like ethanol intake in male C57BL/6J mice. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:555–63. doi: 10.1037/a0015345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linsenbardt DN, Boehm SL., 2nd Agonism of the endocannabinoid system modulates binge-like alcohol intake in male C57BL/6J mice: involvement of the posterior ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2009;164:424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ericson M, Löf E, Stomberg R, Chau P, Söderpalm B. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the anterior, but not posterior, ventral tegmental area mediate ethanol-induced elevation of accumbal dopamine levels. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008;326:76. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Self-infusion of GABA(A) antagonists directly into the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:369–80. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Regional differences within the rat ventral tegmental area for muscimol self-infusions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;61:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodd ZA, Melendez RI, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Zhang Y, Murphy JM, et al. Intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of male Wistar rats: evidence for involvement of dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1050–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1319-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (U.S.). Committee on Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research., National Academies Press (U.S.) Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lister R. Interactions of Ro 15-4513 15-4513 with diazepam, sodium pentobarbital and ethanol in a holeboard test. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1987;28:75–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misslin R, Belzung C, Vogel E. Interaction of RO 15-4513 15-4513 and ethanol on the behaviour of mice: antagonistic or additive effects? Psychopharmacology. 1988;94:392–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00174695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen R, Hanchar H, Meera P, Wallner M. GABA A receptor subtypes: the “one glass of wines receptors. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green A, Grahame N. Ethanol drinking in rodents: is free-choice drinking related to the reinforcing effects of ethanol? Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 2008;42:1. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowak K, McBride W, Lumeng L, Li T, Murphy J. Blocking GABAA receptors in the anterior ventral tegmental area attenuates ethanol intake of the alcohol-preferring P rat. Psychopharmacology. 1998;139:108–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wieland H, Lüddens H, Seeburg P. A single histidine in GABAA receptors is essential for benzodiazepine agonist binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knoflach F, Benke D, Wang Y, Scheurer L, Luddens H, Hamilton BJ, et al. Pharmacological modulation of the diazepam-insensitive recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors alpha 4 beta 2 gamma 2 and alpha 6 beta 2 gamma 2. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1253–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crestani F, Assandri R, Tauber M, Martin JR, Rudolph U. Contribution of the alpha1-GABA(A) receptor subtype to the pharmacological actions of benzodiazepine site inverse agonists. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:679–84. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sur C, Farrar S, Kerby J, Whiting P, Atack J, McKernan R. Preferential coassembly of 4 and subunits of the -aminobutyric acidA receptor in rat thalamus. Molecular pharmacology. 1999;56:110. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Low dose acute alcohol effects on GABA A receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:513–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borghese CM, Werner DF, Topf N, Baron NV, Henderson LA, Boehm SL, 2nd, et al. An isoflurane- and alcohol-insensitive mutant GABA(A) receptor alpha(1) subunit with near-normal apparent affinity for GABA: characterization in heterologous systems and production of knockin mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:208–18. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wallner M, Olsen RW. Physiology and pharmacology of alcohol: the imidazobenzodiazepine alcohol antagonist site on subtypes of GABAA receptors as an opportunity for drug development? Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:288–98. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belelli D, Harrison NL, Maguire J, Macdonald RL, Walker MC, Cope DW. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors: form, pharmacology, and function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12757–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schultz W. Getting Formal with Dopamine and Reward. Neuron. 2002;36:241–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roitman M, Stuber G, Phillips P, Wightman R, Carelli R. Dopamine operates as a subsecond modulator of food seeking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:1265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3823-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koob G. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1992;13:177–84. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laviolette S, van der Kooy D. GABAA receptors in the ventral tegmental area control bidirectional reward signalling between dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neural motivational systems. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;13:1009–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnt J, Scheel-Krüger J. GABA in the ventral tegmental area: differential regional effects on locomotion, aggression and food intake after microinjection of GABA agonists and antagonists. Life sciences. 1979;25:1351–60. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]