Abstract

Objective: Little is known about prevalence and usual treatment of childhood and adolescent recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) in outpatient paediatricians’ practice. This study’s primary objective was to acquire insights into the usual paediatricians’ treatment and their estimation of prevalence, age and gender of RAP patients. Further objectives were to assess to which extent family members of patients report similar symptoms, how paediatricians rate the strain of parents of affected children and adolescents and how paediatricians estimate the demand for psychological support.

Methods: Provided by a medical register, 437 outpatient paediatricians received a questionnaire to assess their perception of several psychosomatic problems and disorders including recurrent abdominal pain.

Results: According to paediatricians’ estimation, 15% of all visits are caused by patients with RAP. In 22% of these cases of RAP, at least one family member has similar problems. In about 15% of all RAP cases, parents ask for professional psychological support concerning their children’s issues, whereas 40% of paediatricians wish for psychological support considering this group of patients.

Conclusions: Estimated frequencies and paediatricians’ demands show the need for evidence-based psychological interventions in RAP to support usual medical treatment.

Keywords: recurrent abdominal pain, RAP, functional abdominal pain, paediatricians, standard medical care, outpatient practice

Abstract

Zielsetzung: Es ist nur wenig über die Häufigkeit und Standardbehandlung wiederkehrender Bauchschmerzen im Kindes- und Jugendalter in Kinderarztpraxen bekannt. Das Hauptziel dieser Studie bestand darin, Einblicke in die Standardbehandlung wiederkehrender Bauchschmerzen zu ermöglichen und eine Einschätzung der befragten Pädiater hinsichtlich Prävalenz, Alter und Geschlecht dieser Patienten zu erhalten. Ein weiteres Befragungsziel war, in welchem Ausmaß andere Familienmitglieder von ähnlichen Beschwerden betroffen sind, wie Kinderärzte die Belastung der Eltern betroffener Kinder und Jugendlicher einschätzen und wie hoch der Bedarf an psychologischer Mitbehandlung ist.

Methodik: Auf Basis einer Liste niedergelassener Kinderärzte wurde 437 Ärzten ein Fragebogen zugestellt, um deren Wahrnehmung verschiedener psychosomatischer Probleme und Störungen einschließlich wiederkehrender Bauchschmerzen zu erfassen.

Ergebnisse: Fünfzehn Prozent aller Besuche in Kinderarztpraxen werden durch wiederkehrende Bauchschmerzen verursacht. In 22% dieser Fälle leidet mindestens ein weiteres Familienmitglied unter vergleichbaren Problemen. In 15% dieser Fälle fragen Eltern nach psychologischer Unterstützung, während sich 40% der Ärzte psychologische Unterstützung für diese Patientengruppe wünschen.

Fazit: Die berichteten Häufigkeiten und der Bedarf an psychologischer Unterstützung zeigen die Notwendigkeit für evidenzbasierte psychologische Interventionen bei wiederkehrenden Bauchschmerzen um die medizinische Standardbehandlung in Kinderarztpraxen zu ergänzen.

Introduction

As early as in childhood and adolescence, recurrent pain is a prevalent health issue. In conjunction with recurrent headache, abdominal pain is the most common pain syndrome in childhood [1]. Organic causes are rarely found; therefore recurrent abdominal pain is often designated as a functional disorder [2]. Prevalence rates concerning this disorder vary considerably, depending on examined sample and used criteria [3]. Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) has been defined in various ways, but the most accepted and traditional definition in research is the one created by Apley & Naish [4]. They define RAP as three or more episodes of abdominal pain that are severe enough to affect daily activities of the child. According to their definition, these symptoms must have occurred at least over a three-months period. Numerous studies take this definition as a basis although it is indistinct and accumulates several functional gastrointestinal disorders. Using Apley & Naish’s definition of RAP, up to 19% of children and adolescents in the general population report abdominal pain severe enough to affect daily activities [3]. Only in a fraction of cases explanatory organic causes can be found [5]. Published studies demonstrate a higher prevalence of RAP in females, with the highest prevalence of symptoms between four and six years and early adolescence [3]. Although only used rarely in epidemiologic studies, the Rome criteria [2] represent the most up to date standard in classification of functional gastrointestinal disorders and differentiate several distinct disorders [5], [6].

According to Starfield et al. [7], RAP is responsible for approximately 2–4% of all visits in paediatrician’s offices, and up to 25% of all referrals to gastrointestinal clinics [8]. RAP children and adolescents use health services more frequently [1], [9], [10] and are often affected by other symptoms which can not be explained by organic causes [9], [11], [12]. Additionally, RAP is accompanied by notable functional impairments, reduced quality of life [13] and school absenteeism [14], [15]. Children suffering from RAP show elevated rates of anxiety, depression and somatization [16], [17], [18], [19], [20] and therefore represent a challenge for paediatricians’ every day work regarding diagnostics and interventions. Studies on course of this disorder show a strong persistence of RAP over years and remarkable associations with irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, depression and mental disorders in general during adulthood [21], [22], [23].

Several studies point to a high efficacy of cognitive-behavioural treatments, which are superior to standard medical care [24], [25], [26]. Up to now, little is known about usual diagnostics and the treatment of RAP in paediatric practice [27], [28]. Hence, this study surveys information from paediatricians about prevalence, current paediatric treatment, demand for specific psychological interventions, the extent to which other family members report similar complaints and how paediatricians estimate the strain of parents of RAP children and adolescents. Supplementary, data of an organic disease were also investigated and served as a comparison group in several analyses: Children suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are heavily burdened by recurrent abdominal pain and functional impairment, similar to children with recurrent abdominal pain without organic origin. Studies comparing children with RAP or IBD with healthy control groups found elevated anxiety scores for both groups and similar levels of abdominal pain [19], [29], [30]. Therefore children suffering from IBD represent an interesting and suitable reference group.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The questionnaire was sent out to registered paediatricians within a radius of 150 km around Tübingen (n=437). The survey was approved by the local (university) ethical board prior to data collection. All paediatricians received the questionnaire via mail and were informed that it would take 10 minutes to complete the survey, that participation is voluntary, but that their support is needed to estimate the demand for psychological support in treating children affected by psychosomatic problems.

Concerning the contents, the questionnaire consisted of six sections: 1.) Paediatricians were asked to estimate the prevalence of RAP, IBD, migraine, tension headache, and sleep disorders in their daily practice („Bitte beantworten Sie folgende Fragen in Bezug auf die Patientenzahl pro Jahr.“, „Störungsbild A: XX% der Kinder, die meine Praxis aufsuchen […] davon XX% weiblich und XX% männlich“/“Please answer following questions in relation to your number of patients per year.”, “Disorder A: XX% of children visiting my office […] thereof XX% female and XX% male”). 2.) To obtain a list of applied treatment strategies, we used an open-answer format to avoid influencing physicians with specific options. 3.) In addition, they were asked whether they had noticed occurrence of these symptoms in family members (siblings, parents) of the children. 4.) A further question („Wie stark schätzen Sie die Belastung der Eltern der betroffenen Kinder bei den einzelnen Krankheitsbildern ein?“/“As how strong do you rate the strain of parents of children affected by these disorders?”) rated the perceived strain of parents of affected children and adolescents on a 5-point-scale from 0 (no strain) to 4 (very heavy strain) for the disorders listed above. 5.) Additionally it was asked how often parents ask for professional psychological support concerning mentioned disorders. 6.) The last section refers to the paediatricians’ demands for co-treatment by psychologists concerning these disorders. Finally, paediatricians were asked for their own sociodemographic data, namely age, gender, duration of their paediatric practice, their status in specialization and continuous medical education and the approximate number of patients seen per quarter.

Data analysis

All data of paediatricians regarding RAP and IBD were included in our analysis. Data were analyzed using the statistical package SPSS 15.0. Most data were analysed by frequencies. Differences between categorical variables were tested by χ²-tests. Differences between means were calculated using the non-parametrical Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test. For comparisons, the statistical level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Respondents

A number of 167 questionnaires returned to the study centre (38.2%). Gender ratio of answering paediatricians is 67 females to 100 males (40.1% vs. 59.9%). The mean age of respondents is M=51.9 years (n=159; SD=8.1; range=35–70; median=52.0). Paediatricians have an overall professional experience of M=21.4 years (SD=9.1) and are in private practice for M=14.6 years (SD=9.2). The average number of cases treated quarterly is M=1246 patients (SD=596.7; range=50–4500). Most frequently mentioned additional qualifications are neuro-paediatrics (10.1%), allergology (9.4%), and homeopathy (7.5%). Five percent have an additional qualification in psychosomatic medicine and 4.9% in psychotherapy whereas 22.6% report no additional qualification.

Analysis of non-responders reveals that the response rate in female paediatricians (50.6%) is significantly higher than in male ones (44.9%) (χ²=16.54; p≤0.001). The distance to the study centre was dichotomized using a median split at 85 km. There is no difference between paediatricians set up near (36.3%) or far (40.4%) from the study centre (χ²=0.762; p=0.38). Further conclusions about non-responding paediatricians cannot be drawn from the available data.

Results

Age, gender and consultations in RAP and IBD

According to paediatricians’ estimations, 15.3% (SD=13.7; Q1=5.0, Q2=10.0, Q3=20.0; range 0–80%) of the visits in paediatricians’ offices are caused by children and adolescents with RAP, while only 1.2% (SD=2.7; Q1=0, Q2=0.5, Q3=1.0; range 0–21%) of patients are suffering from IBD (Z=–10.31; p≤0.001).

The gender ratio in RAP is estimated to be 56.4% females to 43.6% males. Nearly the same ratio is reported for IBD: 55.5% female vs. 44.5% male. Affected RAP children are younger than those suffering from IBD. Paediatricians state that children with RAP are 6.5 years (SD=1.92; Q1=5.0, Q2=6.0, Q3=8.0; range=3.0–11.0) on average, with a peak of age at 5 years and a second peak at 8 years (1st mode=5.0, 10.8%; 2nd mode=8.0, 9.0%). Children with IBD are 12.2 years (SD=2.92; Q1=10.0, Q2=13.0, Q3=14.0; range=4.0–16.0) on average, with a peak at 15 years of age (mode=15.0; 9.0%). This difference in age estimations between RAP and IBD is significant (Z=–5.75; p≤0.001).

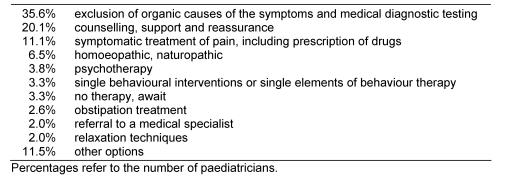

Therapy options in RAP

The most frequently named intervention for RAP (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)) is exclusion of organic causes and medical diagnostic testing with respect to allergies and dietary arrangements (named by 35.6% of paediatricians), followed by counselling, support and reassurance (20.1% of paediatricians) and symptomatic treatment of pain (11.1% of paediatricians), which includes mostly medication and physical therapy such as massage. Psychotherapy is mentioned in only 3.8% of cases, single behavioural interventions or single elements of behaviour therapy are noted in 3.3% of cases. Few (3.3%) paediatricians state that no therapy or treatment is offered to RAP children. Relaxation techniques are mentioned in 2% of cases.

Table 1. Therapy options in RAP.

Since medication treatment is common and the most recommended therapy in children and adolescents suffering from IBD, interventions are not listed.

Family occurrence and parental strain in RAP and IBD

Paediatricians estimate that in 21.7% (SD=20.5; Q1=0.75, Q2=20.0, Q3=30.0; range 0–99%) of RAP cases, at least one family member has similar symptoms. Almost similar results are reported for IBD: In 21.0% (SD=22.7; Q1=0, Q2=10.0, Q3=40.0; range 0–80%) of IBD cases, at least one family member is estimated to have similar symptoms. The definition of “family member” was not further specified (e.g. biological vs. not biological).

Paediatricians rate the strain for parents of affected children and adolescents on a 5-point-scale to be 2.6 (SD=0.75; range 1–4) for RAP, whereas it is 3.4 (SD=0.69; range 1–4) for IBD. A comparison of these data shows that paediatricians score the strain of parents significantly lower for children with RAP compared to children with IBD (Z=–1.19; p<0.001).

Demand for psychological support in RAP and IBD

In 15.0% of RAP children and adolescents, parents ask for professional psychological support for their child (SD=17.8; Q1=1.0, Q2=10.0, Q3=27.5; range=0–90%). Parents of IBD children request additional psychological support in 14.4% of cases (SD=22.0; Q1=0, Q2=5.0, Q3=20.0; range=0–100%). In comparison, the percentage of paediatricians presenting a need for professional psychological support in treating children with RAP reaches 39.6%, whereas only 3% of the paediatricians consider psychological treatment necessary for IBD patients.

Discussion

According to paediatricians’ reports, about 15% of their patients suffer from RAP, while one in 1000 is suffering from IBD. The findings are consistent to several studies which report prevalences of RAP to be up to 19% [3]. The broadly varying estimation of IBD prevalence may reflect the increased incidence rate especially for Crohn’s Disease in the last years [31].

Most studies report a higher prevalence of RAP in females [3]. We find a gender ratio of 1:1.3 for RAP, which is quite consistent with previous investigations which state a gender ratio of 1:1.5 [3], [32], [33], [34], [35]. The current study shows up an average age of six and a half years in children with RAP, with a peak at the age of five and a second peak at eight years of age. Apley and Naish [4] also indicate two peaks of symptom onset: One peak at five and another between eight and ten years of age. In their study, they report a prevalence of 9.5% in boys and 12.3% in girls. With respect to IBD we find an equal prevalence in male and female children. Some authors report a slight female predominance in ulcerative colitis [36], others reference a male dominance in Crohn’s disease [31], [37]. Typically, children with IBD are older than children with RAP when treated by paediatricians. In this study IBD patients are estimated to be 12 years on average, with a peak of age at 15 years.

Furthermore, paediatricians estimate that in about 25% of RAP cases, at least one family member has similar complaints or symptoms. Mühlig and Petermann [38] conclude a familial accumulation of 28%. Parents of children with RAP often suffer from abdominal complaints or from other pain symptoms [12], [39], [40], [41]. Studies on family pain history support evidence for the parents’ modelling influence on the pain behaviour of their children [15], [39], [42], [43]. Children with RAP are exposed to more pain models than children suffering from disorders with known organic origin of pain [44]. As described above, nearly similar results are reported for IBD. Heyman et al. [37] report that 29% of the IBD children have one or more family member with IBD.

A child suffering from chronic pain certainly leads to a situation representing a source of stress and strain for all close family members. The severity of symptoms has a definite effect on the quality of life [45]. Youssef et al. [13] show that RAP and IBD are both significantly connected to lower scores of quality of life compared to a healthy control group. Parents’ perceptions of their children’s quality of life are even lower. This impaired quality of life may be seen in the reported strain on parents in our study. Paediatricians rank the stress between “moderate strain” and “notable strain” for RAP parents, whereas the strain of IBD children and adolescents is rated between “notable strain” and “heavy strain”. A comparison of these data shows that paediatricians score the strain of parents significantly lower for children with RAP compared to children with IBD. These results are in conflict to the study of Youssef et al. [13] who demonstrate a comparable impairment of children with RAP. It is conceivable that paediatricians score the strain for the family in a different way than parents do: One reason could be that paediatricians are influenced by the impact of chronicity of IBD.

For this discrepancy, RAP in paediatric practice is primarily considered as a problem of differential diagnostics and not as a treatment problem: In a survey among paediatricians, Edwards et al. [27] show that the usual treatment for children with abdominal pain essentially consists of an investigation of potential organic causes to be excluded and of comforting children and parents. Doctors may perceive RAP as a problem children will “grow out of”; hence no specific intervention is applied [27]. As a result of this study it is to be stated that counselling, reassuring and clarification of possible organic causes play the major role in handling and treating children with RAP. This finding replicates current literature [27], [46]. Approximately 30 to 40% of children suffering from RAP can be expected to improve if given this type of doctoral support [47]. For children who do not improve, this could have further consequences on the doctor-patient-relationship und may lead to withdrawal and frustration. Beyond that, these interactions have an immense influence on children's perceptions and pain experiences [48]. Although medical clarification is important to rule out organic diseases, a specific psychosocial intervention may prevent a chronic development. This is further supported by the fact that Cochrane Reviews provide weak evidence of benefit of medication in children with RAP and a lack of high quality evidence on the effectiveness of dietary interventions [49], [50]. If heavily strained children are not treated appropriately, they will probably show significantly more abdominal pain, more somatic symptoms, greater functional impairments, more frequent use of health services and more internalizing psychiatric symptoms than healthy children do [22]. Campo et al. [23] ask the striking question, “Do they just grow out of it?“ and show that 11 years after an initial examination, a group of 28 affected children have a higher risk of depression, anxiety disorders and hypochondria. Furthermore, these children have more somatic impairments, a lower level of functioning and take more psychoactive medication than a comparison sample of 28 healthy children [23].

Our results clearly demonstrate that paediatricians show a non-negligible need for psychological support in treating young patients with RAP. They may be well aware of accompanying psychological factors such as anxiety, depression and the unfavourable long-term outcome of RAP, but they do not recommend any specific (psychological) intervention although there is convincing evidence for efficacy. Huertas-Ceballos and colleagues [51] refer to several studies comparing cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) to standard medical care or waiting list. Six controlled studies with randomized assignment to experimental and control-group revealed statistically significant improvements in pain in children receiving CBT compared to children receiving standard medical care or were on wait list. Methodological weaknesses and heterogeneity of the samples complicate the interpretation of reported effects, but there is good evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy is a useful and efficient intervention for children suffering from recurrent abdominal pain [51].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrate that RAP is a prominent problem in paediatric practice, and paediatricians are aware of this, but may not always turn their insights into the appropriate management strategies. The outcome of untreated RAP is undoubtedly unfavourable. More effort is required in order to evaluate specific psychological interventions and to make them public and available to paediatricians.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ellert U, Neuhauser H, Roth-Isigkeit A. Schmerzen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Prävalenz und Inanspruchnahme medizinischer Leistungen. [Pain in children and adolescents in Germany: the prevalence and usage of medical services. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50(5-6):711–717. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0232-8. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00103-007-0232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, Walker LS. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1527–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chitkara DK, Rawat DJ, Talley NJ. The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in western countries: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(8):1868–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41893.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apley J, Naish N. Recurrent abdominal pains: a field survey of 1,000 school children. Arch Dis Child. 1958;33(168):165–170. doi: 10.1136/adc.33.168.165. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.33.168.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker LS, Lipani TA, Greene JW, Caines K, Stutts J, Polk DB, Caplan A, Rasquin-Weber A. Recurrent abdominal pain: symptom subtypes based on the Rome II Criteria for pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38(2):187–191. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00016. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005176-200402000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helgeland H, Flagstad G, Grotta J, Vandvik PO, Kristensen H, Markestad T. Diagnosing pediatric functional abdominal pain in children (4-15 years old) according to the Rome III Criteria: results from a Norwegian prospective study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49(3):309–315. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818de3ab. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818de3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starfield B, Hoekelman R, McCormick M. Who provides health care to children and adolescents in the United States? Pediatrics. 1984;74(6):991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle JT. Recurrent abdominal pain: an update. Pediatr Rev. 1997;18(9):310–320. doi: 10.1542/pir.18-9-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramchandani PG, Hotopf M, Sandhu B, Stein A. The epidemiology of recurrent abdominal pain from 2 to 6 years of age: results of a large, population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):46–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1854. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwille IJ, Giel KE, Ellert U, Zipfel S, Enck P. A community-based survey of abdominal pain prevalence, characteristics, and health care use among children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barr RG, Feuerstein M. Recurrent abdominal pain syndrome: How appropriate are our basic clinical assumptions? In: McGrath PJ, Firestone P, editors. Pediatric and adolescent behavioral medicine. New York: Springer; 1983. pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatization symptoms in pediatric abdominal pain patients: Relation to chronicity of abdominal pain and parent somatization. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19(4):379–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00919084. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00919084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youssef NN, Murphy TG, Langseder AL, Rosh JR. Quality of life for children with functional abdominal pain: a comparison study of patients' and parents' perceptions. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):54–59. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0114. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, Rzepski B, Andrulonis PA. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129(2):220–226. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70246-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Psychosocial correlates of recurrent childhood pain: a comparison of pediatric patients with recurrent abdominal pain, organic illness, and psychiatric disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(2):248–258. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.248. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M, Altman S, Lucas A, Birmaher B, Di Lorenzo C, Iyengar S, Brent DA. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):817–824. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dufton LM, Dunn MJ, Compas BE. Anxiety and somatic complaints in children with recurrent abdominal pain and anxiety disorders. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(2):176–186. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn064. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramchandani PG, Fazel M, Stein A, Wiles N, Hotopf M. The impact of recurrent abdominal pain: predictors of outcome in a large population cohort. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(5):697–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00291.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker LS, Greene JW. Children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents: more somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression than other patient families? J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14(2):231–243. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youssef NN, Atienza K, Langseder AL, Strauss RS. Chronic abdominal pain and depressive symptoms: analysis of the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(3):329–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.019. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker LS, Guite JW, Duke M, Barnard JA, Greene JW. Recurrent abdominal pain: a potential precursor of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr. 1998;132(6):1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70400-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker LS, Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Greene JW. Long-term health outcomes in patients with recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20(2):233–245. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.2.233. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/20.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campo JV, Di Lorenzo C, Chiapetta L. Adult outcomes of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain: do they just grow out of it? Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):e1. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.e1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders MR, Rebgetz M, Morrison M, Bor W, Gordon A, Dadds M, Shepherd R. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of recurrent nonspecific abdominal pain in children: an analysis of generalization, maintenance, and side effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(2):294–300. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.2.294. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins PM, Smith SM, Glutting JJ, Bishop CT. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(5):397–408. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi063. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders MR, Shepherd RW, Cleghorn G, Woolford H. The treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children: a controlled comparison of cognitive-behavioral family intervention and standard pediatric care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(2):306–314. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.2.306. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards MC, Mullins LL, Johnson J, Bernardy N. Survey of paediatricians' management practices for recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1994;19(2):241–253. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/19.2.241. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/19.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGrath PJ, Feldman W. Clinical approach to recurrent abdominal pain in children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1986;7(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/00004703-198602000-00010. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703-198602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorn LD, Campo JC, Thato SP, Dahl RE, Lewin D, Chandra R, Di Lorenzo C. Psychological comorbidity and stress reactivity in children and adolescents with recurrent abdominal pain and anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(1):66–75. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00012. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasserman AL, Whitington PF, Rivara FP. Psychogenic basis for abdominal pain in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(2):179–184. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198803000-00008. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198803000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hildebrand H, Finkel Y, Grahnquist L, Lindholm J, Ekbom A, Askling J. Changing pattern of paediatric inflammatory disease in northern Stockholm 1990-2001. Gut. 2003;52(10):1432–1434. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.10.1432. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.52.10.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alven G. The covariation of common psychosomatic symptoms among children from socio-economically differing residential areas. An epidemiological study. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82(5):484–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12728.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grøholt EK, Stigum H, Nordhagen R, Köhler L. Recurrent pain in children, socio-economic factors and accumulation in families. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18(10):965–975. doi: 10.1023/A:1025889912964. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1025889912964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen S, Bergström E, Brulin C. High prevalence of tiredness and pain in young schoolchildren. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31(5):367–374. doi: 10.1080/14034940210165064. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14034940210165064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AAJM, Hunfeld JAM, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Passchier J, van der Wouden JC. Chronic pain among children and adolescents: Physician consultation and medication use. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(3):229–235. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200009000-00008. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renz-Polster H, Krautzig S, Braun J. Basislernbuch Innere Medizin. München: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heyman M, Kirschner B, Gold B, Ferry G, Baldassano R, Cohen S, Winter HS, Fain P, King C, Smith T, El-Serag HB. Children with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Analysis of a pediatric IBD consortium registry. J Pediatr. 2005;146(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.043. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mühlig S, Petermann F. Idiopathischer Bauchschmerz im Kindesalter: Ergebnisse, Defizite und Perspektiven empirischer Forschung. [Idiopathic abdominal pain in children: results, deficits and perspectives of empirical research]. Schmerz. 1997;11(3):148–157. doi: 10.1007/s004829700017. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004829700017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harbeck C, Peterson L. Elephants dancing in my head: A developmental approach to children's concepts of specific pains. Child Dev. 1992;63(1):138–149. doi: 10.2307/1130908. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1130908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Payne B, Norfleet M. Chronic pain and the family: a review. Pain. 1986;26(1):1–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Routh DK, Ernst AR. Somatization disorder in relatives of children and adolescents with functional abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1984;9(4):427–438. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/9.4.427. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/9.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Violin A, Giurgea D. Familial models for chronic pain. Pain. 1984;18:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90887-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker LS, Claar RL, Garber J. Social consequences of children's pain: When do they encourage symptom maintenance? J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(8):689–698. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.689. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osborne RB, Hatcher JW, Richtsmeier AJ. The role of social modeling in unexplained pediatric pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14(1):43–61. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.1.43. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/14.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loonen HJ, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, de Haan RJ, Bouquet J, Derkx BH. Measuring quality of life in children with inflammatory bowel disease: the impact-II (NL) Qual Life Res. 2002;11(1):47–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1014455702807. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1014455702807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weydert JA, Ball TM, Davis MF. Systematic review of treatments for recurrent abdominal pain. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e1–e11. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scharff L. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: a review of psychological factors and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17(2):145–166. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(96)00001-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(96)00001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dell'Api M, Rennick JE, Rosmus C. Childhood chronic pain and health care professional interactions: shaping the chronic pain experiences of children. J Child Health Care. 2007;11(4):269–286. doi: 10.1177/1367493507082756. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1367493507082756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huertas-Ceballos A, Logan S, Bennett C, Macarthur C. Dietary interventions for recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003019. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003019.pub2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003019.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huertas-Ceballos A, Macarthur C, Logan S. Pharmacological interventions for recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huertas-Ceballos AA, Logan S, Bennett C, Macarthur C. Psychosocial interventions for recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003014.pub2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003014.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]