Abstract

Hispanics are disproportionately affected by substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and HIV. Although the relationship between these conditions has been documented in the literature, few studies have explored the intersection of these health problems and their culture-related risk factors in an integrative manner. The purpose of this study is to explore the experiences that Hispanic heterosexual males in South Florida have with substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors. Three focus groups with a total of 25 Hispanic adult men are completed and analyzed using grounded theory. Three core categories emerge from the data. These include la cuna de problemas sociales (the cradle of social problems), ramas de una sola mata (branches from one same tree), and la mancha negra (the black stain). This study suggests that substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors are linked conditions with common cultural and socioenvironmental risk factors and consequences.

Keywords: mental health, alcohol consumption, illicit or illegal pharmaceuticals, sexuality, violence, focus groups, grounded theory

Introduction

Findings from various epidemiological studies have indicated that Hispanic men in the United States are disproportionately affected by the occurrence and/or consequences of substance abuse (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration [SAMHSA], 2008), intimate partner violence (IPV; Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005), and HIV/AIDS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). Although there is a substantial body of evidence supporting the strong relationships between substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors among Hispanics in the United States (Caetano, Cunradi, Schafer, & Clark, 2000; Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2004; Gonzalez-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia, & Vasquez, 2008; Raj et al., 2006) and documenting a perceived need for these conditions to be addressed among Hispanic communities (Elliot, Quinless, & Parietti, 2000), few studies have explored the intersection of these three health problems and their culture-related risk factors among Hispanic men in an integrative manner. Consequently, there are currently no intervention programs targeting these three health conditions that have been specifically designed for Hispanic men in the United States. Project VIDA (Violence, Intimate Relationships and Drugs among Latinos) is a mixed-method pilot study (i.e., quantitative and qualitative) that aims to explore the experiences of Hispanic heterosexual and MSM (men who have sex with men) with regard to substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors and to identify cultural factors associated with these that would need to be addressed in intervention programs. This article reports on the results of the qualitative component of the project wherein focus group discussions with Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, heterosexual men were completed.

Behavioral Risks Among Hispanic Males

Although reported substance abuse rates among Hispanic adult men is not remarkably different than what is documented among other racial and ethnic groups (SAMHSA, 2008), Hispanics are disproportionately affected by the negative consequences associated with substance use and abuse. For example, Hispanic men are less likely to receive treatment for substance abuse and mental health services than both White and Blacks (Wells, Klap, Koike, & Sherbourne, 2001). Various studies have explored issues relating to substance abuse among Hispanic adults and adolescents and have identified associated cultural factors such as machismo, traditional gender roles and acculturation that may interact with other well-established risk factors for substance abuse (e.g., family history of substance abuse). For example, machismo and traditional gender roles have been identified as an important cultural factor that is related to substance abuse and associated risky behaviors among this population. In a qualitative study exploring alcohol use among young Mexican American men and women, alcohol consumption was perceived by participants as being a cultural inheritance, a measure of male masculinity, and a common cause of arguments with intimate partners (Fiorentino, Berger, & Ramirez, 2007). Other studies have also noted the endorsement of traditional gender roles, which accepts substance abuse and risky sexual behaviors among males and promotes more conservative values among females (e.g., staying at home, sexual modesty), as a risk factor for substance abuse among this population (Torres-Stone & Meyler, 2006). Conversely, caballerismo, ascribing to the positive aspects associated with the male role in Hispanic culture, such as protecting and providing for the family, appears to protect Hispanic males from abusing substances and participating in other risky behaviors (Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, & Tracey, 2008).

Acculturation is another important cultural factor that has been associated with higher rates of substance abuse among this group (Caetano et al., 2004; Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Hayes Nautista, 2005). Immigration issues, language barriers, and cultural assumptions from peers appear to contribute to the acculturative stress that Hispanics experience in the United States (Torres-Stone & Meyler, 2006). More acculturated Hispanic subgroups also appear to be more likely to participate in higher risk substance abuse such as needle sharing (Delgado, Lundgren, Deshpande, Lonsdale, & Purington, 2008). This may be because this population is less exposed to culturally appropriate harm-reduction messages that provide information regarding risks associated with sharing needles, where to access clean needles, how needles can be cleaned, and how to better manage injection risks.

Some research studies have indicated that Hispanics report higher rates of IPV than non-Hispanics (Caetano et al., 2005) and that IPV disproportionately affects certain Hispanic subgroups such as Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans (Aldarondo, Kaufman-Kantor, & Jasinski, 2002; Kaufman Kantor, Jasinski, & Aldarondo, 1994). Little is known regarding the experiences Hispanic men have with IPV and the associated cultural factors because most of the qualitative studies conducted in this area have focused on women’s experiences disclosing abuse. These studies have identified the important role that confianza (“trust,” which includes confidentiality, support, comfort, and safety) plays in establishing the type of relationships with providers that would encourage disclosure of IPV by Hispanic women (Rodriguez, Bauer, Flores-Ortiz, & Szkupinski-Quiroga, 1998; Shoultz, Phillion, Noone, & Tanner, 2002). Other studies have explored IPV among Hispanic women as a component of HIV-related risk factors and/or substance abuse. These have identified machismo, acculturation, and stress associated with changes in the traditional roles of women and men in intimate relationships on arrival to the United States, documentation status, self-esteem and partner’s substance abuse as important factors that may place Hispanic women at risk for IPV (Gonzalez-Guarda, 2008; Peragallo, DeForge, Khoury, Rivero, & Talashek, 2002).

Although Hispanics in the United States accounted for 15% of the population in 2006, they accounted for 17% of all new HIV infections. In fact, the prevalence of HIV among Hispanic men is more than twice the rate for White men (CDC, 2008). The majority of studies exploring the experiences Hispanic have with HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and/or risky sexual behaviors have primarily focused on Hispanic women, adolescents, or MSM. The few studies that have included Hispanic heterosexual men have primarily focused on factors needed in prevention programs for couples. Important components of HIV prevention programs targeting Hispanic couples include activities that increase partner communication, safer sex decision making, access to condoms, condom use and information relating to other STIs. Activities that address financial concerns relating to testing and treatment have also been identified as important for these programs (Sormanti, Pereira, El-Bassel, Witte, & Gilbert, 2001). In a study conducted by Singer et al. (2006), additional barriers to partner communication and condom or barrier contraceptive negotiation among Hispanics and other ethnic groups were identified. These included being raised in a poor family and neighborhood, living in a “broken home” (e.g., single-parent home), experiencing domestic violence, limited expectations of the future, limited exposure to positive role models, lack of expectation of the dependency of others, machismo, infidelity, and fear of intimacy (Singer et al., 2006). Despite the fact that these studies have provided rich information regarding the type of services and programs that are needed for Hispanic men, there continues to be a lack of information regarding the actual experiences that this population has with risky behaviors and the cultural factors associated with these.

Method

The larger study of Project VIDA used a triangulated mixed-method design in which both quantitative and qualitative data are collected at approximately the same time, and equal priority is given to each. The strength of this approach is that the strength of one method offsets the limitations of the other (Creswell, 2002). Although the quantitative data that was collected will help summarize phenomena and test relationships between these, the qualitative data can yield a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The dearth of literature on the experiences of Hispanic men related to substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors led to the selection of grounded theory methodology to guide the qualitative component of the study (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Grounded theory is a systematic qualitative research method emphasizing generation of theory from data. This article reports the findings from the qualitative focus groups of Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, heterosexual men. The focus groups were divided by sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual vs. homosexual) and preferred language. The majority of the men accepting the invitation to participate in the heterosexual focus group were either bilingual (English and Spanish) or preferred to participate in a Spanish-speaking group. Consequently, there were not enough individuals who preferred speaking in English to organize an English-speaking group. The homosexual focus group data will be analyzed and reported separately.

Sample

To be eligible for the study participants had to self-identify as a Hispanic male between the ages of 18 and 55 and living in South Florida at the time of screening. Individuals who reported being tourists or planning to move in the following year were excluded from the study. Potential participants were recruited into Project VIDA through posting or handing out flyers at shopping centers, Hispanic-serving businesses, nightclubs, community clinics, and community events. Snowball sampling methods were also used. After participants finished their quantitative interviews, they were invited to participate in the focus groups. Information regarding availability to participate, sexual orientation, and language preference were collected at this time. Candidates expressing interest in participating in the groups and reporting that they were heterosexual and preferred to speak in Spanish were grouped together so that the discussions from these groups would yield rich information about Hispanics with these characteristics. Therefore, this study used purposive sampling to recruit participants. Three focus groups with a total of 25 participants (i.e., 8–9 participants per group) were completed in a private conference room in an office building located in downtown Miami, Florida.

Procedures

Before recruiting participants for the study, IRB approval was obtained. Signed informed consent was completed by each study participant before starting the focus group discussion. The sharing of food, getting acquainted, consent process, and focus group took approximately 2.0 hours to complete, with approximately 1.5 hours of group discussion. Each focus group was facilitated by a coinvestigator of the project, the main moderator, and a doctoral student, the comoderator. Participants were compensated $30 in cash on completion of the focus group to compensate for time and travel. At the beginning of the focus group, anonymity and confidentially of the participants were ensured. Time was given to the participants to eat the food that was served, get acquainted with each other, and become familiarized with the moderators. Initial data were gathered by using a semistructured interview guide that contained an opening question and general questions regarding experiences of Hispanic men in their community with substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors. If participants had difficulty discussing these topics, additional probing questions were provided to elicit more information (see Table 1). In using a constant comparative analysis technique, question and probes were added and/or modified based on findings from the previous focus group. For example, in the first focus group the participant’s criminal history came up as an area of major concern. Because specific questions related to criminal history had not been initially included in the focus group guide, additional questions were added to elicit more information regarding this topic. The question regarding the relationship between the three major conditions of focus were not introduced until the end of the discussion. Further inquiry was done to clarify and expand on the experiences and ideas that were presented by asking participants to provide examples for further explanation. All focus groups were audio-recorded.

Table 1.

Initial Questions and Examples of Probes for Hispanic, Spanish Speaking, Heterosexual Men Participating in Project VIDA Focus Groups

|

Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in Spanish by a transcription service. The moderators verified the transcripts by listening to the original recording and comparing the transcription to the actual words of the participants. All discrepancies were corrected. Data analysis was completed by two bilingual investigators in the original Spanish language. Transcribed focus group interviews were analyzed line by line. Data describing the experiences of Hispanic male participants were coded (open coding) and compiled in a list. As the transcripts were reviewed, new data were compared to existing data (constant comparison; Glaser, 1992; Swanson & Chenitz, 1982). Constant comparison allows for the continued integration of accumulated knowledge. Through concurrent data collection and data analysis, patterns within the data emerged, and focused questioning guided further collection of data. Categories were constantly modified as successive data demanded. Relationships between data that emerged were also coded throughout the data analysis process (axial coding). Data that clustered together were then assigned to core categories. Data were further scrutinized to identify saturation of ideas and recurrent patterns of comparable and dissimilar meanings. Saturation was reached with the third focus group. Subcategories, categories, core categories, results, and recommendations were abstracted from the data. During the analysis process, findings were traced back to raw data to ensure credibility of the data. Peer debriefing was used to establish credibility. Peer debriefing exposes the process of inquiry to a peer (experienced researcher with Hispanic populations) for the purpose of establishing the credibility of the inquiry. This study established credibility by sharing the raw data with two senior researchers who were not present in the focus group and did not participate in the data analysis. All raw data, data analysis, and synthesis products were saved and were available for auditing, a method of evaluating conformability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results

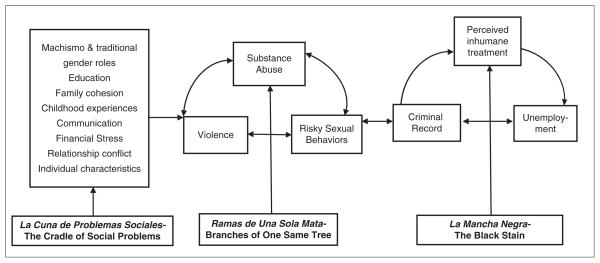

A total of 25 Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, heterosexual men participated in three separate focus groups (i.e., 8–9 participants in each group). Three major themes were identified. These included ramas de una sola mata (branches of one same tree), la cuna de los problemas sociales (the cradle of all the social problems), and La Mancha Negra (the Black Stain). These categories were organized according to the relationship and processes identified in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationship between the causes, nature, and consequences of substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic men in South Florida

Participant characteristics

Focus group participants were born in various countries in Latin America, with the majority reporting being born in Cuba (44.0%), the United States (16.0%), Honduras (12.0%), and Nicaragua (12.0%). The number of years participants reported living in the United States ranged from 1 year to 46 years (M = 23.84, SD = 11.61). Their ages ranged from 28 to 56, with a mean of 44 years of age (SD = 9.17). The majority were unemployed (96.0%), single (60.0%), did not currently live with a partner (80.0%), and had no health insurance (84.0%). The mean number of years of education that was reported was 10.52 years (SD = 3.80). The majority of participants earned less than $500 a month (68.0%) or between $500 and $999 a month (12.0%). Most participants reported that their health was either fair (37.5%) or good (37.5%), based on a Likert-type scale ranging from very poor to very good.

Ramas de Una Sola Mata (Branches of One Same Tree)

Substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors were seen as being closely related and being “branches of the same tree.” During all of the focus groups, the intersection of substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors emerged from the very beginning or throughout the middle of the discussion without being probed to make this connection. For example, in the first few minutes of one of the focus groups, participants began to mention areas of concern for Hispanic men in the community. Participants immediately mentioned substance abuse, violence, and HIV as areas of major concern. While participants discussed which one of these was most frequently observed in the community, one participant stated, “todos juntos” (all together). Other participants echoed his statement in agreement with this idea. During other focus groups, relationships between these were drawn while focusing on each of these areas separately. For example, participants described substance abuse as a risk factor for relationship conflict and aggression that often resulted in domestic violence. They also identified substance abuse as a major risk factor for risky sexual behaviors such as infidelity, intercourse without condoms, and prostitution. In turn, domestic violence was also identified as a risk factor for substance abuse. Victims and perpetrators of domestic violence at times turned to substance abuse to deal with the trauma of being victimized or having their partners leave them after perpetrating abuse.

At the end of one of the focus groups, the moderator asked the participants how substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors were related. One participant described the relationship between these conditions in depth, describing how alcohol and illicit drugs lead to domestic violence and consequent separation from family and depression. Men use alcohol and illicit drugs to escape depression and may even engage in prostitution to support drug-abusing behaviors.

Drugs make you forget about protection. Drugs, alcohol, that goes with the drugs also, put you in a state that you do not care about anything. Hmm, it creates domestic violence. Domestic violence creates separation, separation creates depression, depression creates alcoholism, as you said, and also creates prostitution, because you prostitute yourself. In reality they all are related, they go hand in hand with all of them. Being by one way or the other, but all having to do with it. And at the end the disease, AIDS, and then death.

Although participants had varying opinions about the order in which these conditions appeared, they all agreed that these were conditions that clustered together in society and were important problems that needed to be addressed among the Hispanic community.

Specific experiences with substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors as individual problems were also described in depth. Many participants reported histories of substance abuse and dependence. Alcohol, marijuana, heroin, ecstasy, amphetamines, crack, and cocaine use were all mentioned as being prevalent in their communities. Participants described how the preference for these substances were somewhat determined by their countries of origin and their social contexts. For example, although it was more common for Puerto Ricans who were born and raised in New York or in Puerto Rico to report heroin as the drug of primary use, crack and cocaine were more commonly reported among Hispanics who had spent more time living in South Florida, regardless of country of origin.

Participants also discussed community and domestic violence. They identified drug-related violence, crimes, rape, and discrimination as being major problems in their communities. Participants spent more time discussing domestic violence than other forms of violence. Physical, sexual, verbal, and emotional forms of partner abuse were identified as being perpetrated by both women and men. However, there was a group consensus that women were more at risk for being victims of partner violence than men because of the physical, cultural, and social factors that made them more vulnerable. Child physical and sexual abuse were also identified as community problems. Lastly, participants expressed their perceptions that Hispanic men, in general, were more risky sexually than White American men because they were “more sexual.” They defined more sexual as having a stronger interest in participating in sexual activities, much of which were risky and included having multiple sexual partners, being unfaithful, and seeking prostitution. Participants also perceived Hispanic men as being less likely than White Americans to use condoms, even when they were aware that they were infected with HIV or other STIs.

La Cuna de los Problemas Sociales (The Cradle of Social Problems)

Various risk factors for substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors were identified throughout the focus groups. Although some participants listed these independently for each condition that was discussed, others discussed risk factors in more general terms and tied these to all of the conditions. Many participants described lack of education and a poor family upbringing as being a major factor associated with these conditions. As one participant described it, this is “the cradle of all the social problems.”

Machismo and traditional gender roles was identified as being one of the cultural values instilled in them during their upbringing that were associated with the social problems being discussed. Participants described how the importance of being strong, aggressive, the heads of their family, being able to drink heavily and “having” many women was ingrained in them throughout their upbringing. As one participant said, “Instead of a cup of milk, they would give me a cup of rum.” Another participant described his perception of the role that machismo plays in placing Hispanic men at risk. He said,

It’s hard for us [Hispanic men] because of the machismo, because of the very same machismo that we have and because of the upbringing we have in our countries. Because in our countries there are small places where everyone points to the woman. “Yes, he cheated on her.” Then for us, the men, that can have seven or eight women while our woman is cooking at home and is taking care of us, cleaning clothes, ironing the clothes. Then we bring it out [being unfaithful to her] and she cannot say anything.

Participants felt that the transition involved in immigrating to the United States and adapting to a new culture challenged these traditional gender roles, created conflicts between couples, and served as a risk factor for domestic violence. One participant explained this in depth,

That in our countries … the machismo, uh, the man in the marriage is truly the person who has the word. It’s like in the majority of the times, the man is the one that pays, the woman stays in the house, and then we get here. We get here right? And there is more violence because many women arrive here and want to change the culture … and then here is when the conflict starts…. The man, we like machismo, and the woman wants to be liberated because she gets here and her culture changes.

Participants also described how they felt that Hispanic women were able to obtain employment more easily than Hispanic men and were more likely to find higher paying work. Feelings of frustration regarding their partners’ ability to obtain work when they could not were also expressed. This may have exacerbated the participant’s sense of loss of control and contributed to more IPV.

Other factors present during their upbringing as children were identified as being risk factors associated with substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic men. Some of these included negative examples provided by family members (e.g., unfaithful and/or abusive fathers), lack of parental attention, harsh parental disciplinary actions (e.g., child abuse), lack of communication in the household (e.g., not discussing sex), and the lack of education regarding these issues in schools and in the community.

Other situations participants were exposed to as adults, such as financial stress, loneliness, and relationship conflict, were also identified as major risk factors for substance abuse, violence, and risk for HIV infection. Many participants described their expectations of immigration that were incongruent with the reality they encountered in the United States. Instead of achieving economic stability as they expected, many encountered difficulty in obtaining employment. Economic hardships often led to frustration, stress, depression, low self-esteem, strained relationships, and in some cases aggression that was manifested toward their female partners or other men. Substance abuse was often used to escape the economic stress and its consequences. In addition, participants reported experiencing a great deal of loneliness, especially if they left their families and friends in their countries of origin and had difficulty developing new relationships. They described how these feelings of solitude and depression also lead to risky sexual behaviors (e.g., promiscuity, prostitution) and substance abuse (e.g., drinking to escape solitude).

La Mancha Negra (The Black Stain)

La mancha negra (the black stain) was coined by a participant who described the difficulty he faced in breaking away from the cycle of substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors because he had a criminal record. Obtaining employment was perceived as being essential in breaking free from these conditions and hechando palante (moving ahead in life). However, because many of the participants had a criminal record, and hence a “black stain” that followed them wherever employment was sought, participants were unable to obtain the jobs that they perceived to be qualified for. Being without employment led them back into substance abuse and associated risky and criminal behaviors. The participant who coined this term stated,

Every time that I look for a job, a job that I understand and can do … boom! The black stain on your back … because as a lot of us have mentioned that we are like that [having a criminal record] in this country. Because of the record, we have to return once again to selling drugs, to fill the streets with drugs, to steal, to assault.

Other participants in the group agreed. They continued to describe this black stain as being a major impediment to changing their lives. They felt that friends, families, employers, government, and society in general treated them inhumanely because of their criminal records and history of substance abuse. The idea of the black stain can be better understood through the lens of one of the participants of the focus group. The participant described his countless attempts to find employment in the transportation and hotel industries and being denied repeatedly for these positions solely because he had a criminal record. The participant reporting feeling frustrated, because despite spending a great deal of effort in trying to find a job, none were available to him. Consequently, he was living out of homeless shelters throughout the city. He also felt that these shelters “shut the door” to him because they had constraints in terms of the length of time residents could sleep there. As it was described, “When we are going to try, to try to rehabilitate ourselves in our addiction, it is very difficult to rehabilitate ourselves because they [potential employers, homeless shelters] shut the door.”

One young participant explained how his black stain caused him to lose his daughter. His daughter was previously taken away from him and his partner because of their substance abuse. Although he was several years without use, the court would not give him custody. As he described, “That discrimination that I would continue to give drugs to others. You see? I disagree and every time that I have arrived to the court, I have paid for what I have done. But until when? That black stamp on the back.” Other participants also felt that it was not just or humane to continue to pay for a crime or mistake throughout a lifetime, even after having done retribution for it. One participant provided an example of a black stain that resonated with the others in the group. He said,

Like for example, that same DUI (driving under the influence) that they put on people that says that it lasts 99 years on your license. Neither an elephant nor a person lives 99 years! [Participants laugh.] If you paid for the DUI … if you paid for it and did not have an accident, you did not bring upon the death of anyone, your little school that they make you do and you passed all of that, why does this need to continue? That record, hanging over you?

This participant was referring to the label and criminal record that is given to individuals who are convicted with a DUI. Despite doing retribution for the charge (e.g., paying the fine, serving a sentence, taking a class) they are never forgiven by society because this conviction can be seen by anyone conducting a criminal history check. Therefore, the consequences have a life-long impact.

Discussion

The results from this study on substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, heterosexual males are important because relatively little attention has been given to the intersection of these factors among this population. The first theme, the cradle of social problems (la cuna de problemas sociales), underscores the important role that cultural factors play in influencing substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic men. The participants from this study viewed the foundation of Hispanic culture as being the family, where gender roles and behaviors are learned. They perceived traditional Hispanic families as encouraging machismo behaviors in males and promoting multiple sexual partners, unprotected sex, and physical and emotional aggression toward women. As was also identified in this study, Hispanic women are encouraged to be more passive and subservient toward men. Consequently, women may defer decision making to their male partners and are often reluctant to discuss family and sexual matters both within and outside of the family unit. These traditional gender roles have been well documented in the literature (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008; Marin, 2003; Marin, Gomez, Tschann, & Gregorich, 1997; Peragallo et al., 2002). If these behaviors, gender roles, and communication patterns are observed as part of the childhood experience and during times of financial stress or relationship conflict, the pattern may be repeated in adulthood. If men are more dominant and in control of the relationship and women are more passive and accepting of the male privilege, these women may be at an increased risk for emotional, physical, and possibly sexual violence within the relationship (Galanti, 2003) and the acquisition of HIV or other STIs through the risk posed by their male partners (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008; Marin et al., 1997; Peragallo et al., 2002).

It also appears that the experience of immigration to the United States challenges traditional gender roles and creates additional stressors that may place this group at risk for substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors. Women who may not have worked in their countries and work in the United States may begin to feel that they have more power and control in making decisions regarding their household. This may challenge the more traditional “patriarchal” structure that was in place, especially if the man is unable to find work as easily as his partner, as was suggested by the participants of this study. In addition, participants describe the major role that the difficulty in finding employment and isolation plays, stressors that may disproportionately affect Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, or immigrant males in the United States in increasing their risk. More research investigating the role that immigration plays in challenging traditional gender roles among Hispanic families, creating stress and leading to IPV (e.g., loss of locus of control, self-esteem among males), and other risk behaviors should be further explored.

Machismo and the encouragement of traditional gender roles and values within Hispanic families also have positive aspects that may protect Hispanic men from substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors. The positive aspects of machismo have sometimes been termed caballerismo (Arciniega et al., 2008; Torres, 1998). Hispanic families stress the role of the male as a strong family protector and provider. Male children who observe adult males in this manner tend to have more pride and affiliation with Hispanic culture and cope with problems using problem-solving skills without reliance on substance use, violence, or engaging in sexual relations outside of the primary relationship (Arciniega et al., 2008). This may be one of the reasons why lower rates of acculturation and ascribing to traditional cultural values have been associated with lower rates of substance abuse and sexual risk behaviors among this population (Caetano et al., 2005; Lara et al., 2005). What is less known in the literature is how the acculturation process interacts with traditional Hispanic views on gender roles to predict risky behaviors among this population. This needs to be further examined to obtain a deeper understanding of the underlying risk and protective factors that may link these behaviors.

The first theme, branches of one same tree (ramas de una sola mata), speaks to the intersection or the syndemic of substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors among the Hispanic men in this study. Despite the fact that numerous studies have documented substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors in Hispanic populations, few studies have examined the intersection of these factors among a community sample of Hispanic, Spanish-speaking heterosexual men. Given the fact that substance abuse (Wells et al., 2001), violence (Caetano et al., 2005), and high rates of HIV infection and other STIs related to high-risk sexual behaviors (CDC, 2008) are more common among Hispanic men, the relationship of these factors must also be explored. The vast majority of previous research in this area has focused on the causes of each of these factors individually without examining the relationships between the factors. Because substance abuse, violence, and unsafe sexual behaviors are all considered high-risk behaviors, participation in one high-risk behavior may influence participation in other high-risk behaviors. This study supports previous research and provides evidence of the relationships of substance abuse, violence, and high-risk sexual behaviors among Hispanic men with similar characteristics to the participants of this study. Consequently, in accordance with the syndemic approach, which looks at intertwined epidemics, these conditions are rooted in common social conditions such as poverty and discrimination (Singer et al., 2006). Although some of these social conditions were identified within the theme of la cuna de los problemas socials (the cradle of social problems), more research needs to be focused on the most important or determinant conditions that link these conditions together and account for the burden of disease that affect Hispanic men in particular.

The last theme, the black stain (la mancha negra), addresses the unique social consequences of substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors faced by Hispanic men, including poverty and discrimination. The men in this study were possibly at risk for poverty and discrimination related to a variety of factors, including ethnic-minority status, language barriers, and for the majority, immigration status. These factors, in combination with a history of a criminal record may have resulted in less financial and social resources for these men as they struggled to achieve success. Nevertheless, it is difficult to ascertain if poverty and discrimination was a consequence, risk factor, or both, based on the results of the focus group findings. The theme “the black stain” captures the difficulty that this subpopulation faces in moving ahead in life, despite a strong desire to do so. This strong desire was evidenced by participants’ descriptions of measures they took to rehabilitate themselves and find employment, and the repetition of statements relating to wanting to move ahead in life. The conflict between internal forces (e.g., will to obtain job and remain abstinent) and oppositional external forces (e.g., discrimination because of criminal history) may create a feeling of hopelessness that may negatively affect the physical and mental health of those who have been disadvantaged, discriminated against, and oppressed. The inability to secure employment further increases financial hardship and poverty. Over time, these social factors have the potential to decrease social support and self-esteem and may result in participation in high-risk activities (Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001) such as substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors.

This study had various limitations that need to be discussed. The participants of the study were not representative of the local Miami, Florida, population in that individuals who were unemployed, abused substances, and had criminal histories were overrepresented in the focus groups. This may have resulted from the recruitment methods that were initially used to engage candidates into Project VIDA. Because individuals who participated in the study were encouraged to tell their family and friends (i.e., snowball sampling methods), individuals with greatest needs (e.g., history substance abuse) and less time conflicts (e.g., work commitment) may have been more likely to participate in the study. However the countries of origins that were represented in the focus group did resemble the characteristics of Hispanics living in Miami, Florida, where Cubans comprise the largest Hispanic subgroup, followed by individuals from Central and South American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). In addition to limitations to the transferability of the data generated in this study, participants may have felt embarrassed fully disclosing their opinions and perspectives, especially if they knew someone else participating in the group. In addition, given that focus groups involve group discussions, the possibility of one member of the group influencing other member’s perspectives is an assumed risk. Although these possible limitations were addressed by highlighting the importance of maintaining confidentiality and avoiding judgment when establishing the ground rules for the focus group, it difficult to completely eliminate these. Despite these limitations, a great deal was learned about an important and high-risk segment of the Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, heterosexual male population in Miami, FL.

Interventions developed for heterosexual Hispanic men with similar characteristics to the sample described in this study and that aim to decrease substance use, violence, and risky sexual behaviors must incorporate three essential elements. First, the influence of culture and cultural factors must be addressed by incorporating these into interventions. Hispanic men should be educated on the role that machismo, immigration status, and the acculturation process may place them at risk or protect them from risky behaviors. By having a deeper understanding of these processes, they may be better equipped to manage their risks. For example, a family intervention can be developed to encourage parents to emphasize the positive aspects of machismo (i.e., caballerismo) while raising their children and discourage the negative aspects that promote aggression and risky behaviors in Hispanic males. Second, to decrease substance abuse, violence, and sexual behaviors, all three conditions must be viewed as intertwined and closely related. Addressing all three conditions in tandem may be more efficacious in decreasing all high-risk behaviors. For example, a holistic health curriculum regarding substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors should be developed for schools that acknowledge the strong connections between these and discuss these connections. Lastly, the influence of poverty, discrimination, and other social issues must be considered. Hispanic men who are disadvantaged are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors in an attempt to cope with stressors. To break the cycle of poverty, discrimination, substance abuse, and crime, interventions are needed to assist Hispanic men who carry a “black stain” in obtaining employment and achieving healthy intimate and social relationships. For example, by providing support for employers who are willing to hire individuals with criminal histories (e.g., providing additional supervision for their employees, creating tax incentives for employers), new employment opportunities can be created for this population and the cycle could be broken.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure/Funding

This study was funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (1P60 MD002266-01, Nilda Peragallo, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aldarondo E, Kaufman-Kantor GK, Jasinski JL. Risk marker analysis for wife assault in Latino families. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:429–454. [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, Tracey TJG. Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a traditional machismo and caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(1):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Schafer J, Clark CL. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11(2):123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field GA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20(9):1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. Acculturation, drinking and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U.S.: A longitudinal analysis. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(1):60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among Hispanics. 2008 Retrieved February 10, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/hispanic.htm.

- Creswell JW. Mixed method designs. In: Creswell JW, editor. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall; 2002. pp. 559–600. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Lundgren LM, Deshpande A, Lonsdale J, Purington T. The association between acculturation and needle sharing among Puerto Rican injection drug users. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2008;31:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from three U.S. cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot NL, Quinless FW, Parietti ES. Assessment of a Newark neighborhood: Process and outcomes. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2000;17:221–224. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1704_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino DD, Berger DE, Ramirez JR. Drinking and driving among high-risk young Mexican-American men. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2007;39:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanti GA. The Hispanic family and male-female relationships: An overview. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14:180–185. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM. Substance abuse, violence and risk for HIV among a community sample of Hispanic women. Dissertation Abstracts International, Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2008;69:1566. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, Vasquez EP. HIV risk, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic females and their partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman Kantor G, Jasinski J, Aldarondo E. Sociocultural status and incidence of marital violence in Hispanic families. Violence and Victims. 1994;9(3):207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Hayes Nautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14:186–192. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV, Gomez CA, Tschann J, Gregorich S. Condom use and unmarried Latino men: A test of cultural constructs. Health Psychology. 1997;16:458–467. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragallo N, DeForge B, Rivero R, Khoury Z, Talashek M. Latinas’ perspective on HIV/AIDS: Cultural issues to consider in prevention. Hispanic Health Care International. 2002;1(1):11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1873–1978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, Flores-Ortiz Y, Szkupinski-Quiroga S. Factors affecting patient-physician communication for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. The Journal of Family Practice. 1998;47:309–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoultz J, Phillion N, Noone J, Tanner B. Listening to women: Culturally tailoring the violence prevention guidelines from the Put Prevention Into Practice Program. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2002;14:307–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: Understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:2010–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Pereira L, El-Bassel N, Witte S, Gilbert L. The role of community consultants in designing an HIV prevention intervention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13:311–328. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.4.311.21431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. Prevalence of substance use among racial & ethnic subgroups in the United States. 2008 Retrieved December 10, 2008, from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NHSDA/ethnic/ethn1006.htm.

- Swanson J, Chenitz W. Why qualitative research in nursing? Nursing Outlook. 1982;30(4):241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JB. Masculinity and gender roles among Puerto Rican men: Machismo on the U.S. mainland. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(1):16–26. doi: 10.1037/h0080266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Stone RA, Meyler D. Identifying potential risk and protective factors among non-metropolitan Latino youth: Cultural implications for substance use research. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2006;9:95–107. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Miami-Dade county, FL, American community survey demographic and housing estimates: 2005–2007. American FactFinder; 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2009, from http://factfinder.census.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]