Abstract

Hispanic females are disproportionately affected by substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and HIV. Despite these disparities, research describing the cultural and gender-specific experiences of Hispanic women with regard to these conditions is lacking. The purpose of this study is to describe the experiences that Hispanic community-dwelling women have with regard to substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors. Eight focus groups with 81 women were conducted. A bilingual, bicultural moderator asked women open-ended questions regarding the experiences that Hispanic women have with these conditions. Focus groups were audiotaped, transcribed, translated, verified, and then analyzed using qualitative content analysis. Participants discussed substance abuse, violence, and risky sexual behaviors interchangeably, often identifying common risk factors associated with these. Nevertheless, intimate partner violence was the most salient of conditions discussed. Three major themes emerged from the analysis: Transplantadas en otro mundo (Uprooted in another world), El criador de abuso (The breeding ground of abuse), and Rompiendo el silencio (Breaking the silence). This study supports the importance of addressing substance abuse, violence, and risk for HIV in an integrated manner and stresses the importance of addressing associated cultural factors (e.g., acculturation, machismo) in interventions targeting Hispanics.

Keywords: community health, focus group analysis, women’s health, Hispanics

Introduction

Hispanics, the largest and fastest growing minority group in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006), are disproportionately affected by substance abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV), and risks for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In fact, some studies have indicated that Hispanics report higher rates of drug and alcohol abuse (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration [SAMSHA], 2007), IPV (Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005), and HIV/AIDS (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 2008) when compared with non-Hispanic Whites and other minority groups. It has also been noted that Hispanics are disproportionately affected by the consequences of these conditions. For example, Hispanics living with AIDS are more likely to die within 9 years of diagnosis than Whites and Asians (CDC, 2008). Hispanics are also more likely to report an unmet need for substance abuse treatment and mental health (SAMSHA, 2007) and report more severe mental health consequences of IPV than Whites and other minority groups (Caetano & Cunradi, 2003). Despite these disparities, research describing the cultural and gender-specific experiences of Hispanic women with substance abuse, IPV, and risky sexual behaviors is lacking. The purpose of this study is to explore the experiences that Hispanic women in the community have with substance abuse, IPV, and risky sexual behaviors.

The SAVA (Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS) Syndemic

The research conducted by Merrill Singer and colleagues with inner-city ethnic minorities (Singer, 1996; Singer & Clair, 2003) has supported the idea that substance abuse, IPV, and HIV/AIDS can be conceptualized as being part of a syndemic. Syndemics are interacting epidemics or conditions that tend to occur in clusters, interact synergistically, and together contribute to an excess in morbidity and mortality among affected groups (CDC, 2009; Singer, 1996). The SAVA syndemic is a specific cluster of epidemics that have been found among marginalized subsamples of Hispanics in the northeast region of the United States with identified histories of high-risk behaviors (e.g., histories of commercial sex work, injection drug use; Singer, 1996; Singer & Clair, 2003). It is unclear if this syndemic also applies to community samples of Hispanic women in other areas of the United States who may not be as “marginalized” because of the large number of Hispanics in the region and who have no other preidentified risk other than their ethnicity and gender. Despite the growing body of literature aiming to quantify the intersection between substance abuse, IPV, and HIV (Newcomb, Locke, & Goodyear, 2003; Suarez-Al-Adam, Raffaelli, & O’Leary, 2000), few studies have explored these three conditions under one framework (Geilen et al., 2007). This study is the first to examine the experiences of Hispanic community women in South Florida with regard to the SAVA conditions and to identify potential cultural factors that may link these conditions together.

Method

Design

Project DYVA (Drogas y Violencia en Las Americas [Drugs and Violence in the Americas]) was a pilot study that explored SAVA conditions among Hispanic community-dwelling women in South Florida through the use of both qualitative (Phase I) and quantitative (Phase II) research methods. This article reports on the first phase of the project, wherein qualitative research methods were used to understand the experiences Hispanic women have with the SAVA conditions.

Participants and Setting

Eligibility criteria for the study included self-identifying as being of Hispanic or Latino descent (i.e., regardless of birth place), female, Spanish or English speaking, and aged between 18 and 60 years. Participants were primarily recruited from a community-based organization that provides a series of social services (e.g., English classes, career development, child care, parenting, etc.) to Hispanics immigrants in South Florida. Study flyers were posted in the reception area, and the receptionist was trained to inform clients about the study. Candidates were given the name and contact information of the study coordinator in case they had any questions the receptionist could not answer. Snowball sampling techniques were also used (Miles & Huberman, 1994). For example, participants who had already enrolled in the study were asked to inform their family and friends who met study inclusion criteria. An article introducing Project DYVA was written in the local newspaper during recruitment. Interested candidates contacted the research coordinator after reading the article.

Procedures

Approval from the university’s institutional review board was obtained prior to recruiting and collecting data for the study. Eight focus groups, with a total of 81 participants (8–13 participants per group), were led by the same bilingual, bicultural facilitator(s) who obtained informed consent and led the focus group discussions. The vast majority of participants (98%) preferred to speak in Spanish. Consequently, all focus groups were conducted in Spanish, which lasted between 1½ and 2 hours and were recorded using a digital audio recorder.

Prior to beginning the focus groups, food and refreshments were served. This allowed the participants and the facilitators to get to know each another and helped build rapport. After the refreshments, the facilitator reviewed and collected the signed consent forms, emphasized the importance of maintaining confidentiality, and established ground rules for the focus group discussion. The ground rules stressed the importance of ensuring that everyone had an opportunity to speak, respecting each other’s privacy and confidentiality, refraining from using specific names for individuals, and moving through topics within the allotted time.

The facilitator used a focus group guide to initiate discussion. This guide included an opening question (e.g., “Because women are the backbones of their communities, they are usually aware of the issues happening in their communities. What are some of the issues facing communities like yours?”) and open-ended questions relating to substance abuse, IPV, and risky sexual behaviors (e.g., “What are some concerns that women from your community have with substance abuse?”). If participants did not mention details about substance abuse, IPV, or risky sexual behaviors in their communities, additional probes were used to elicit perspectives regarding these issues (e.g., “What are the circumstances that surround conflicts in intimate relationships in your community?”). Participants were paid $50 on the completion of the focus group to compensate them for their time and travel and child care costs. Once the focus groups were completed, participants were scheduled for face-to-face interviews in which a battery of standardized instruments (e.g., demographic form, violence assessment, acculturation) was administered (Gonzalez-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia, & Vasquez, 2008).

Data Analysis

The audiotaped focus groups were transcribed and translated by bilingual study personnel. After the Spanish transcripts were translated, one of the coinvestigators compared the original Spanish transcription with the English translation and revised any discrepancies. These transcripts were then analyzed using content analysis. Content analysis is a research technique that allows investigators to make inferences from text or other media that are valid and replicable. Procedures used in content analysis vary depending on the purpose of its use (Krippendorff, 2004). Because the purpose of this study was to describe the experiences of Hispanic women with the SAVA conditions from an “emic,” or insider’s, perspective, the conventional qualitative content analysis approach was taken (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Five bilingual, bicultural investigators reviewed the seven focus group transcripts, making sure that each transcript was analyzed by two investigators and that every investigator analyzed two or more transcripts. Seven of the eight focus group transcripts (N = 72) were included in this analysis. One of the focus groups (Focus Group 4, n = 9) could not be analyzed because the digital recording file was corrupted and could not be heard. Although investigators reviewed the transcripts in the language they felt most comfortable with (i.e., English or Spanish), each transcript was analyzed by at least one investigator in its original Spanish language.

Clear steps for conducting the qualitative content analysis were developed based on the work of experts in the field (Flinck, Paavilainen, & Astedt-Kurki, 2005; Krippendorff, 2004; Mayring, 2000) and distributed to five investigators in order to ensure that every investigator was using the same analysis technique. These steps included reading through the transcripts several times, identifying significant statements (i.e., meaning units), clustering these into subcategories and categories, and finally identifying underlining threads or themes. Differences in opinions among coders were resolved by reflecting on the underlying meanings that categories and themes attempted to capture, linking them to the direct quotations from participants, and discussing these until agreement was reached on the appropriate categorizations and themes.

Findings

Participant Characteristics

Participants varied with regard to age (M = 39.28, SD = 10.91) and years living in the United States (M = 9.31, SD = 8.26). Participants represented almost all the countries in Latin America, with the greatest proportions coming from Colombia (47.6%), Venezuela (13.4%), and Ecuador (8.5%). Despite the fact that participants had a high level of education (M = 14.28, SD = 3.87), they reported a low mean individual (M = 493.05, SD = 791.90) and household monthly income (M = 2766.35, SD = 3943.07). The majority of the participants were unemployed (59.8%), did not have health insurance (65.6%), and were married (59.8%) or currently living with their partner (64.6%). All but two participants preferred speaking in Spanish and were immigrants. The two participants reporting that they preferred to speak in English also felt comfortable speaking in Spanish and participated in the focus groups conducted in Spanish.

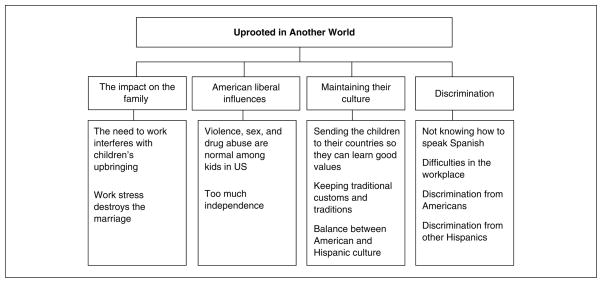

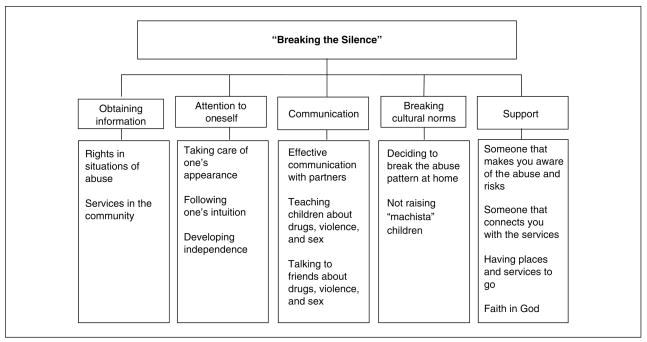

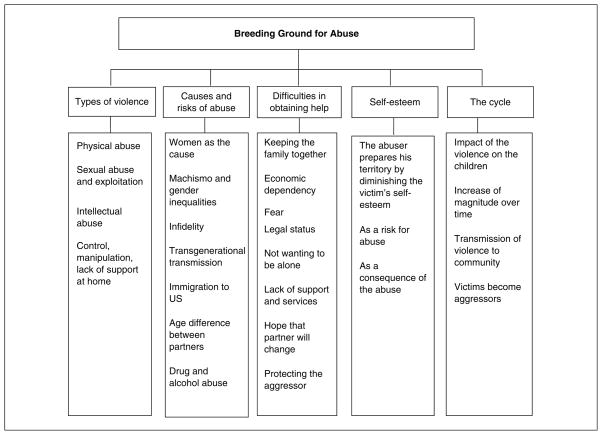

Three central themes emerged from the focus group data. These themes and their respective categories and subcategories are visually displayed in Figures 1 to 3.

Figure 1.

Categories and subcategories of Theme 1, Transplantadas en otro mundo (Uprooted in another world)

Figure 3.

Categories and subcategories of Theme 3, Rompiendo el silencio (Breaking the silence)

Uprooted in another world (Transplantadas en Otrol Mundo)

Participants provided rich descriptions of their experiences immigrating to the United States and how living in a world where a different language was spoken, different customs were practiced, and different values were upheld threatened their communities, cultural roots, and personal dignity. Participants spoke a great deal about how immigrating to the United States had directly affected their families. They voiced a constant struggled to preserve the integrity of their families amidst a society in which their work responsibilities challenged the time they could dedicate to them. As one woman described,

It [moving to the United States] changes those values that you bring from your country. It changes the family as the base of a society, it is replaced by work and the children that are banished from one’s mind … consequently leaving the children and ourselves in a state of emotional fragility.

Other women described their fears about their children being raised in a more “liberal” society where risky behaviors were more acceptable. They related this more liberal lifestyle to an increased risk for the SAVA conditions. One woman said, “Here, the young people are very liberated. Here, everything is liberal. Here, everything is normal, children leave their homes, they get pregnant, they have sex with other partners, they smoke or take drugs. Like, it is all so normal.”

Focus group participants repeatedly spoke about how children in their countries of origin were more respectful than American kids and the importance of maintaining one’s own culture. Many spoke about taking their children back to visit the countries they came from. They viewed this as a technique that helped them preserve the “innocence” of the children and protected them from the risk of substance abuse, IPV, and risky sexual behaviors. Participants also described the discrimination they faced in the United States from both non-Hispanic Whites and other Hispanics who were not immigrants and were proficient in English. Many of the participants held high-level jobs in their countries of origin and had to assume service jobs such as housekeeping because of not being able to speak English. They felt that they had to settle for jobs that they were overqualified for because of language discrimination.

The breeding ground for abuse (El Criador de Abuso)

Although participants discussed issues relating to substance abuse and HIV risks, they focused more of their attention on IPV, often relating substance abuse and HIV risks back to IPV. When participants spoke about IPV, they identified its different forms and levels of severity. They also placed the abuse within a context that included the causes and risk factors for IPV. Moreover, they discussed the difficulties in leaving abusive relationships, self-esteem as a risk and consequence, and the cycle of abuse. This context was often referred to as la crianza que nos han dado—“the upbringing/legacy that they have given us.”

When describing the actual types of IPV, special attention was given to psychological forms of abuse. They characterized this type of abuse by describing power and control tactics used by their partners. These tactics varied in level of blatancy, ranging from covert intellectual competition to more overt threats of physical harm. One of the participants was the pastor of her church and spoke about how her ex-husband, who was also a pastor, constantly competed with her in respect to who had the most knowledge. She said,

Let’s see now, intellectual violence has nothing to do with beatings, nothing to do with screaming, it is competitive pressure, it is a competition and especially when both partners are professionals. It is competition based on intellectual power to see who knows more, who wins more, who dominates more.

Other women spoke of more physical and sexual forms of abuse. One woman described how her husband beat her when she complained about her son crying all day. She said,

Then he arrived at night. I complained one moment because all day I was with my son and he cried, and cried, and cried, and I was tired … and once again he hit me. When he lifted me, he grabbed me by the neck, threw on the bed and hit me, hit me, hit me.

Although some participants described very aggressive forms of sexual abuse such as rape, the majority discussed more overt types of sexual abuse, such as having sex with one’s husband out of obligation.

Participants also spoke about the causes and risk factors for the different types of abuse they described. Machismo was a term that was frequently used by the participants, regardless of their country of origin, to describe their experiences with culturally based gender inequalities and the role that this played in increasing their risk for abuse. The macho, as they described, had more privileges than the women and often assumed ownership of their wives. One young Cuban woman spoke about her husband’s perception of ownership when discussing machismo and disclosing physical, sexual, and psychological abuse by her current husband, saying,

And he violated me in the most brutal way a woman can be violated. In every way possible that they want to have sex, even if you don’t want to, destroyed and many times bleeding … and he would say, “I am your husband, I own you.”

When describing the role that machismo played in placing them at risk for IPV, participants also discussed how machismo promoted substance abuse and risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic men. For example, one woman said,

[In the voice of a man] “I’m a man and I can have sex with 10 women without a condom.” American men won’t have sex with a woman who doesn’t want any protection, but our machos go to bed with anybody.

Another woman described how machismo influences substance abuse. She said, “And the men say ‘I want to drink my beer, to relax,’ and there he drinks his beer all night until the next day, and the woman stays in the house tolerating it because they want to relax.”

Participants believed that machismo and gender inequalities that were so ingrained in their culture that they as women continued to perpetuate it. As one woman said, “the women who have children, males, raise potential machistas. We are, even though the victims of men, also, creators of machismo, so that they go and become aggressive with other women whom will be our daughters-in-laws.” This woman and other women described how differences in the manner in which they brought up their male and female children (e.g., not allowing boys to express emotions, giving boys more liberty and girls more responsibilities) encouraged machismo and was a large part of “breeding” the next generation of perpetrators and victims.

Participants described the various obstacles their community faced in addressing IPV and the other SAVA conditions. One of the barriers was lack of information about the nature of these problems, their legal rights, and how to access community resources. Economic barriers and the desire to preserve the family unit were also described as being a reason why women tolerated abuse from their partners. Another barrier to addressing these conditions was a perceived lack of police support and difficulty in accessing social services, especially for women who were undocumented.

Self-esteem was an important category imbedded in the breeding ground for abuse, as it was described as being a risk for, a consequence of, and part of the processes involved in the SAVA conditions. One of the younger participants explained,

When you don’t love yourself, you allow people to step all over you, and when people step all over you, you can fall into drugs … your self-esteem is so low, you can fall into domestic violence and fall into sexual abuse.

Last, participants described the abuse as a cycle that escalated in severity over time and was transmitted in various ways (i.e., from the perpetrator to the victim, to the perpetrator’s children, and to the community). One woman described how she became violent after years of victimization. As she stated,

Because he was aggressive and I became aggressive, and one day he went to hit me and I got a knife and I told him, “Leave, leave, that I am going to kill you.” And I was going to kill him. I was going to kill him. I was crazed.

Breaking the silence (Rompiendo el Silencio)

Participants repeated rompiendo el silencio numerous times during the focus group discussions when referring to breaking the cycle of abuse and breaking cultural norms and taboos relating to substance abuse and sexual behaviors. To break the silence, they highlighted the importance of having access to information about their rights in the United States and how to access services in the community, especially if they were undocumented. They also highlighted the importance of knowing where to go or to whom to consult with for help. As one woman put it, “I don’t know what to invent so that when a Latino comes to this country they know where to go … because depending on the path or whom they know, that will be how it will go for them.”

Paying more attention to oneself was an important aspect involved in being able to “break the silence.” This included paying more attention to one’s physical appearance, following their own intuitions, and fostering their own independence. One woman described the day that she decided to leave her abusive relationship. She described,

I looked at myself in the mirror, “What is it that you want from life? You want your life or to continue in this relationship or that he comes one day and kills the son or kills me? Or you want to change your life?” And that was it. I made the decision.

Participants believed that part of breaking the silence was also increasing effective communication between partners and their children. Some participants described their belief that if there is good communication between partners that address problems before they arise, abuse will never result. Part of partner communication was being able to break the silence surrounding sex and being able to negotiate condom use. In fact, participants expressed concern about the possibility of their partners being unfaithful and how they were embarrassed to ask them to use condoms. Increasing communication to their children in order to break cultural taboos and norms related to the SAVA conditions.

Participants also stressed the importance of receiving support from others and having access to services when making the decision. One of the older participants of the focus group said,

The woman, so that she can decide (to leave an abusive relationship) needs someone to take her and tell her, “aren’t you aware of what is happening?” But when someone says I will help you, that is the most beautiful word.

One young Colombian woman spoke about how the advice from others helped her make the decision to leave her abusive husband. She was undocumented, and in addition to the fear of being abused by her husband, she was concerned about being deported. As she stated,

And when I went to a place, they told me, because I was scared. At that moment I was illegal and was scared. And people told me, “don’t be afraid because the women that shut their mouths are the women who die.”

Faith in God also played an important role in helping women overcome their abusive situations and begin the healing process.

Discussion

This study describes the experiences of Hispanic women in South Florida with regard to the SAVA conditions. The major themes that emerged from the focus group data provide a rich description of the cultural factors (e.g., trust in health and social services, machismo, acculturation) that shape the context for the SAVA conditions among Hispanic women. Many of the findings of this study are supported by the work that others have reported in the literature. In a study conducted by Belknap and Sayeed (2003), the investigators explored the thoughts and feelings of abused Mexican American women regarding being asked about IPV by a health care provider (screening). They found that the participants were open to being asked about their histories of abuse if they felt that their health care provider was attentive to their needs, asked about other aspects of their lives, listened to their responses, and assisted them in connecting with IPV community services. This was consistent with our experience, as women were open to disclosing intimate life details about their abuse and stressed the importance of having someone helping them break the silence surrounding it.

Kasturirangan and Williams (2003) explored the experiences of Hispanic female victims of IPV. The main domains they identified included the misperception of the “typical Hispanic female,” cultural experiences in the United States, the influence of traditional gender roles in their upbringing, the perception of family support, reasons for staying and/or leaving the abusive partner, and their desired characteristics of the type of counseling and counselor they wished to have access to. These are consistent with our findings as participants described the difficulties they encountered living in the United States (i.e., uprooted in another world); the role that machismo and gender inequalities played in IPV, substance abuse, and HIV risks; and the countless obstacles they encountered in accessing help (i.e., the breeding ground for abuse). Peragallo, DeForge, Khoury, Rivero, and Talashek (2002) focused on identifying cultural factors that related to HIV prevention among a group of Mexican and Puerto Rican women and identified similar themes. Socioeconomic and cultural inequalities, machismo and marianismo, lack of knowledge about HIV, and a history of abuse were identified by women as risk factors for HIV. In this study, participants also reported lack of support and services (i.e., socioeconomic and cultural inequalities) and machismo and infidelity as risk factors for IPV and HIV.

There appears to be reemerging themes found among qualitative research conducted with Hispanic females, despite the specific questions posed by the investigators and the diversity in regard to the Hispanic samples that have been included (e.g., country of origin, age). These themes allude to the cultural factors associated with gender inequalities (or sometimes called machismo), the stress associated with living within and acculturating to a different culture, and the wide range of barriers encountered in accessing support (e.g., lack of information, inadequate culturally appropriate services, insurance status) that place Hispanics at risk for the SAVA conditions.

In addition to underscoring important cultural factors associated with the SAVA conditions that have been previously identified in the literature, there are unique findings from this study that need to be highlighted. The first is the fact that participants discussed the SAVA conditions interchangeably, often describing common risk factors (e.g., machismo, self-esteem). This is consistent with the findings that Singer (1996) came across during his work among “higher risk” Hispanics in the northeast region of the United States and the syndemic approach, which identifies clusters of conditions that occur together and focuses on their common links or risk factors (CDC, 2009). The categories and subcategories identified under the major themes of this study can serve as potential links to these conditions. These links and the potential for targeting these to prevent the SAVA syndemic among Hispanics should be further explored in research. Nevertheless, the participants of this study appeared to be most concerned with IPV. This may be because IPV was the most prevalent of the three conditions, as documented in the second phase of Project DYVA (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008). Although the participants did not stress their own substance abuse and HIV behaviors throughout the focus group discussion, they did focus a great deal on their partners’ promiscuity and risky behaviors, connecting machismo and gender inequalities to their own risk for IPV and HIV.

This study has numerous limitations that must be considered in the interpretation of the results. One of the limitations was that the focus groups consisted of a convenience sample of a relatively low acculturated group of immigrant Hispanic women who preferred to speak Spanish and scored low on the U.S. acculturation subscale (Marin & Gamba, 1996) administrated in the second phase of this study. Therefore, the findings may not represent the experiences of other Hispanic women in South Florida or other areas of the United States with different characteristics (e.g., U.S.-born). Additionally, because many of the participants may have known one another other (e.g., as a result of snowball sampling), they may have felt embarrassed about talking about these sensitive issues. The focus group methodology is further threatened by the potential of having one or more participants dominate and lead the discussion. This may cause other less vocal members of the group feel inhibited in sharing their views and opinions.

Implications for Research and Practice

This study supports the need to conduct more research describing the interaction between the SAVA conditions and the common risk and protective factors that cut across these. For example, machismo and gender inequities emerged as a risk factor for all the SAVA conditions. Consequently, interventions that focus on changing perceptions regarding gender norms and promoting equity between males and females may hold promise in preventing all three of these conditions.

As the theme “uprooted in another world” implies, the experience of living in the United States, where the predominant culture is different from one’s own, cannot be separated from the experiences of Hispanic women with regard to substance abuse, IPV, and risky sexual behaviors. Therefore, cultural issues relating to the impact that moving to the United States has on the family, their cultural values, and their experiences with discrimination need to be addressed in research, practice, and programs targeting this group. For example, health services required of immigrants on their arrival to the United States (e.g., HIV and STI testing) can expand their programs to include education regarding the factors that place Hispanic in the United States at an increase risk for the SAVA conditions and community resources they can access to prevent and address these. The second theme, “breeding ground for abuse,” can specifically be used for designing research studies that explore risk and protective factors for IPV among Hispanic women. This will support the development of prevention and treatment programs that target specific cultural (e.g., machismo and gender inequalities) and environmental factors (i.e., lack of support services) that may place a Hispanic woman at risk. Because one of these risks appears to be their partner’s behaviors, prevention efforts targeting women can be more successful if they also address men. For example, to prevent Hispanic females from being victims of IPV or being infected by HIV, programs that address substance abuse among their partners also need to be developed, integrated into these programs, and formally evaluated. The last theme, “breaking the silence,” offers providers and researchers with clues to what type of strategies can be used when caring for victims of IPV and women at risk for substance abuse and HIV (e.g., making information about rights and community services available, promoting independence), how to promote communication about these issues (e.g., teaching parent how to discuss issues with children and partners), what cultural norms need to be broken (e.g., teaching mothers how to not raise machistas), and what type of support is needed (e.g., access to someone that can connect IPV victims to support services).

In summary, various cultural factors appear to play an integral role in shaping the experiences that Hispanic women have with the SAVA conditions. For research and programs targeting this population to be both culturally appropriate and effective, these factors should be considered.

Figure 2.

Categories and subcategories of Theme 2, Criador de abuso (Breeding ground for abuse)

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors received financial support for the research of this article through the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD), and financial support for the authorship of this article through the National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (1P60 MD002266-01, Nilda Peragallo, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Belknap RA, Sayeed P. Te contaria mi vida: I would tell you my life, if only you would ask. Health Care for Women International. 2003;24:723–737. doi: 10.1080/07399330390227454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks and Hispanics. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003;13:661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field C, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The five year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. HIV/AIDS among Hispanics/Latinos. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/hispanic.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Syndemics prevention network. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/syndemics/index.htm.

- Flinck A, Paavilainen E, Astedt-Kurki P. Survival of intimate partner violence as experienced by women. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14:383–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geilen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JB, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2007;8:178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, Vasquez EP. HIV risk, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic females and their partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasturirangan A, Williams EN. Counseling Latina battered women: A qualitative study of the Latina perspective. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2003;31(3):62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba R. A new measure of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BASH) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:287–316. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2000;1(2) Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Locke TF, Goodyear RK. Childhood experiences and psychosocial influences among HIV risk among adolescent Latinas in southern California. Cultural Diversity in Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:219–235. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragallo N, DeForge BR, Khoury Z, Rivero R, Talashek ML. Latina’s perspectives on HIV/AIDS: Cultural issues to consider in prevention. Hispanic Health Care International. 2002;1(1):11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 1996;24:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in biosocial context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17:423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Al-Adam M, Raffaelli M, O’Leary A. Influence of abuse and partner hypermasculinity on the sexual behavior of Latinas. AIDS Education and Prevention. 12:263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. Rockville, MD: Author; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k6nsduh/2k6Results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Nation’s population one-third minority. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb06-72.html.