Abstract

Following stimulation through their T cell receptor, invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells act as innate effector cells by rapidly releasing large amounts of effector cytokines and chemokines and therefore have an important role in modulating the ensuing immune response. iNKT cells recognize and are activated by diverse glycolipid antigens, many of which are found in microorganisms. However, iNKT cells also demonstrate some reactivity to “self”. Here, I outline our current understanding of iNKT cell autoreactivity and propose that several self-lipids are probably involved in the positive selection and autoreactivity of iNKT cells.

Introduction

Natural Killer T (NKT) cells represent a distinct subset of T lymphocytes1, 2 that can enhance or suppress immune responses through the rapid and potent release of cytokines1, 3 (Box 1). For this reason, NKT cells are often regarded as potential therapeutic targets and numerous studies in humans and mice have reported a strong association between NKT cell defects and increased susceptibility to many autoimmune diseases and cancers1, 4–6. Type I NKT cells, also named iNKT cells, are the most prevalent NKT cells in mice7 and are the focus of this article. iNKT cells express a semi-invariant T cell receptor (TCR) composed of a single invariant TCRα chain, which in combination with certain TCRβ chains, recognizes the non-polymorphic MHC class I molecule CD1d.

Box 1. iNKT cells and the immune response.

Natural Killer T (NKT) cells represent a distinct subset of T lymphocytes that express an αβ T cell receptor (TCR). Most of them, but not all, also express several markers usually associated with the NK lineage from which they have derived their name. NKT cell TCRs recognizes lipid antigens presented by the non-polymorphic MHC class I molecule, CD1d. Type I NKT cells, also named iNKT cells, are the most common CD1d-restricted T cells in mice. These cells are conserved in humans where they represent a lesser proportion of CD1d-reactive T cells. iNKT cells are characterized by the expression of an invariant TCRα chain (Vα14-Jα18 in mice, Vα24-Jα18 in human) in combination with certain TCRβ chains (using Vβ8.2, 7 or Vβ2 in mice, Vβ11 in human). They recognize the prototypical glycosphingolipid antigen α-galactosylceramide, and are best identified using CD1d tetramer loaded with this antigen. iNKT cells express a memory or activated phenotype (CD62L−CD69+CD44high IL-2Rβhigh) and in mice they are either CD4+ or double-negative (DN) cells. Even in absence of priming, iNKT cell stimulation through their TCR leads to the rapid production of several effector chemokines and cytokines, including IL-4 and IFNγ, which in turn leads to a cascade of events that results in the activation of antigen-presenting cells and many other bystander cells (including NK, T and B cells). The diversity and extent of iNKT cell cytokine production leads to a broad range of effects, ranging from enhanced cell-mediated immunity (T helper 1 (TH1)-type responses) to suppressed cell-mediated immunity (TH2-type responses) and iNKT cells have been implicated in both the progression and the resolution of diverse animal models of disease. This remarkable ability to regulate many different aspects of immunity, gave them the metaphorical title of the “Swiss-Army knife” of the immune system84.

From the onset of their discovery, iNKT cells have been shown to have some reactivity toward ‘self’. Some mouse iNKT cell hybridomas8, 9, a fraction of freshly isolated mouse iNKT thymocytes9, and some human iNKT cell clones10, all exhibited autoreactivity in a TCR-dependent manner and this reactivity could be blocked by anti-CD1d antibodies. In all cases, reactivity was achieved in the absence of exogenous antigen added to the cultures and it was unclear whether the iNKT cell TCR recognized the CD1d molecule itself or if CD1d might present some self antigens to activate their autoreactivity. The findings that CD1d molecules are absolutely required for the thymic development of iNKT cells11–13 and that some iNKT cells respond to CD1d-expressing APCs, including thymocytes9,14, bone marrow derived dendritic cells and various CD1d transfected cell lines15–18, suggested that the self-antigen(s) presented by CD1d molecules for positive selection of iNKT cells and triggering of iNKT cell autoreactivity might in fact be the same. This notion is very surprising when one considers that the self-peptides that induce the positive selection of thymocytes are likely to be different from the peptides that induce full cellular activation of mature conventional T cells19.

Such a concept led to the idea that iNKT cells represent ‘innate’ lymphocytes that are autoreactive by design20 and are selected through the recognition of agonist self-antigen(s) in the thymus. Consistent with this hypothesis, several markers usually associated with antigen-experienced T cells are expressed by iNKT cells in the steady state21–23, and iNKT cells constitutively express effector cytokine mRNA (IL-4 and IFNγ)24, 25, suggesting that they might be continuously stimulated by self antigens. In addition to the role that this autoreactivity might play in the surveillance against tumors26, 27, recent findings have revealed that iNKT cell activation can occur through the recognition of CD1d-restricted self-antigens when combined with inflammatory cytokines released by antigen-presenting cells. This observation introduces the possibility that iNKT cell activation could occur in response to virtually every infectious agent28.

Understanding the nature of the self-antigen(s) that are presented by CD1d and are critical to the development and function of iNKT cells is therefore fundamental to defining the biological relevance of this cell population. Several self-lipids and glycolipids have now been isolated and shown to be presented by CD1d, yet, it remains unclear which one(s) is/are important for triggering iNKT cell autoreactivity and which one(s) is/are responsible for the positive selection of iNKT cells in the thymus. Here, I review our current understanding of iNKT cell autoreactivity, how it might be triggered, and argue that several self-lipids are likely involved in the process.

iNKT cell self antigen(s)

All of the microbe-derived iNKT cell antigens isolated to date29–33 share a common structure when bound with CD1d: a lipid tail buried in CD1d that is linked by an α linkage to a sugar head group that protrudes out of CD1d to be recognized by the iNKT cell TCR34, 35. However, any endogenous ligand for iNKT cells is likely to differ significantly from this structure, given that mammals cannot synthesize α-linked glycolipids.

CD1d molecules can capture self-lipids in the endoplasmic reticulum of APCs, along the secretory pathway to the cell surface, or in the endosomes/lysosomes during recycling36. Many different self-lipids, including phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylglycerol, glycosylphosphatidylinositol, cardiolipin, sphingomyelin, lysophospholipids, plasmalogens, gangliosides and other glycosphingolipids have been shown to bind CD1d molecules37–40.

To date, one mouse iNKT cell hybridoma41, 42 and one human iNKT cell clone43 have been shown to respond to CD1d molecules loaded with phosphatidylethanolamine or phosphatidylinositol. Most mouse and human iNKT cells, however, do not respond to these phospholipids, suggesting that these hybridoma and clones might represent a subset of iNKT cells that can recognize CD1d-presented phospholipids. Recent findings also showed that a fraction of human iNKT cells can be stimulated by lysophosphatidylcholine and lysosphingomyelin that were loaded onto CD1d at the surface of APCs44. Such reactivity has not yet been extended to mouse iNKT cells, and it is unclear what role these lysophospholipids might have in iNKT cell development. Indeed, several studies have indicated that the self-antigen(s) recognized by mouse iNKT cells are loaded onto CD1d molecules within endosomal vesicles and require specialized processing steps at this site16, 18, 45, 46, whereas, such requirements apparently do not apply to some human iNKT cell clones47, 48. In agreement with the idea that the self-antigen(s) recognized by iNKT cells in peripheral tissues might be the same to the ones presented in the thymus in the course of development, this endosomal loading of self-antigen(s) is also needed for the positive selection of mouse iNKT cells, as demonstrated using mice expressing a tail-mutated version of CD1d that prevents its recycling within the endosomal compartment45. The glycosphingolipid β-glucosylceramide (βGluCer), but not β-galactosylceramide (βGalCer), has been proposed as a precursor of natural self-antigen(s) presented by CD1d molecules to mouse iNKT cells15, 49, 50. Furthermore, mice lacking the lysosomal enzyme β-hexosaminidase B (HEXB), were shown to have a severe deficiency in iNKT cell numbers38. Therefore, glycosphingolipids with terminal N-acetyl galactosamine (GalNAc) sugars, which are cleaved by β-hexosaminidases, were thought to be potential precursors for an iNKT cell ligand(s). However, only the β-linked glycosphingolipid isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) proved to be an agonist for mouse and human iNKT cells when presented by CD1d molecules in a cell-free assay38 and thymocytes from Hexb−/− mice failed to stimulate an iNKT cell hybridoma38, suggesting that iGb3 alone might be responsible for the thymic selection and the self-reactivity of iNKT cells51.

Recently, the role of iGb3 as the sole self-glycolipid involved in iNKT cell autoreactivity and in iNKT cell thymic selection has been challenged. iNKT cell deficiencies were found in several knockout mouse models that have an accumulation of glycosphingolipids in the late endosomes/lysosomes, irrespective of the specific glycosphingolipid targeted52. These results suggest that the deficiency in iNKT cells observed in Hexb−/− mice might be due to the non-specific accumulation of glycosphingolipids, which may alter proper antigen loading of CD1d molecules within the endosomal compartment, rather than the absence of a particular self-ligand. In addition, direct biochemical analysis of glycolipids isolated from mouse or human thymi and peripheral dendritic cells (DCs) failed to detect iGb353, 54 and mice deficient for the iGb3 synthase (also known as A3GALT2) showed no obvious iNKT cell defect53. Finally, it was reported that humans lack a functional iGb3 synthase and that iGb3 is therefore absent in human APCs55. Together, these results suggested that iGb3 might not be essential for iNKT cell development and self-recognition.

However, it is possible that minute quantities of iGb3 within the endosomal/lysosomal compartment could have been missed in the above analyses. Moreover, other biochemical pathway(s) in the absence of functional iGb3 synthase could potentially lead to the production of iGb3 in the endosomes/lysosomes56. In fact, very low levels of the iGb3 compound in the mouse thymus, DCs49 and melanoma cell line57 and of iGb4 in the human thymus58 have been detected. But if iGb3 is indeed the ligand responsible for the selection and autoreactivity of iNKT cells, how many iGb3–CD1d complexes on the cell surface of thymocytes or APCs are necessary and sufficient to induce positive selection and/or a response by iNKT cells? Recent studies showed that about 10 peptide–MHC complexes were needed for a sustained calcium response in CD4+ T cells59, and that only three peptide–MHC complexes were needed for the induction of cytotoxicity by CD8+ T cells60. Considering these observations, perhaps minuscule quantities of iGb3 are relevant to iNKT cell autoreactivity and thymic selection. Alternatively, it is also possible that several self antigens, including iGb3, could trigger the autoreactivity of certain iNKT cell hybridomas and positively select iNKT cells in vivo.

Although the role of iGb3 as the singular, or at least the dominant, selecting ligand is uncertain, it remains the most potent agonistic self-antigen described to date. Other β-linked glycosphingolipids such as βGalCer have been shown to stimulate iNKT cells61, 62. However, these results could be in part due to the potential contamination by α-linked glycosphingolipids that can occur during the synthesis of these compounds. Further experiments will clarify whether βGalCer (and other β-linked glycosphingolipids) are bona fide iNKT cell antigens.

In addition to phospholipids and glycosphingolipids, glycodiacylglycerols could also include potential self-antigens for iNKT cells. A glycodiacylglycerol purified from the Gram-negative bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi binds to CD1d molecules and can be recognized by iNKT cells31 indicating that iNKT cell ligands are not limited to glycosphingolipids. Because these compounds, including monohexose α-linked diacylglycerol, have been identified in animal tissues63, 64, it is possible that self-glycodiacylglycerols might also represent self-antigen(s) for iNKT cells.

Together, these data illustrate that several, structurally unrelated, self-lipids can potentially stimulate iNKT cells. It remains unclear, however, whether human and mouse iNKT cells might recognize different self-antigens. We also do not know whether subpopulations of iNKT cells have distinct antigen specificities or whether the whole iNKT cell repertoire has overall the same antigenic specificity but only iNKT cells that express the highest affinity TCRs respond to the lowest affinity antigens. Finally, the circumstances leading to the presentation of each one of these various self-antigens and how they might be involved in triggering an iNKT cell response remain completely unknown.

Triggering an iNKT cell response to “self”

Although examples of iNKT cell autoreactivity clearly exist, in general, most iNKT cells respond minimally to CD1d-expressing APCs. However, when APCs are exposed to microbial or viral pathogens, they can stimulate iNKT cells in a CD1d-dependent manner that does not require microbial or viral antigens. Therefore, APCs can sense pathogens and increase the autoreactivity of iNKT cells. Such a phenomenon might be mediated through the recognition of specific self-antigen(s) that are otherwise not presented in the steady state by CD1d molecules, and/or that various foreign antigen-independent mechanisms that increase the sensitivity of the responding iNKT cells to self-ligands might be at play.

Weak responses to self-antigen–CD1d complexes by human CD1d-restricted T cell clones can be amplified by IL-12 produced by DCs in response to microbial products30, 50, 65 (Fig 1). In addition, activation of nucleic acid sensors expressed by DCs, such as TLR9, can also indirectly trigger the production of IFNγ by iNKT cells66. However, while in some studies the activation of iNKT cells by TLR9-activated DCs depended on the secretion of IFNβ (or IL-12) and the recognition of self glycolipid(s) presented by CD1d50, 66, in other studies iNKT cell activation relied on the production of IL-12 but the need for CD1d expression was relatively minor67–69. The reasons for such discrepancies are unresolved.

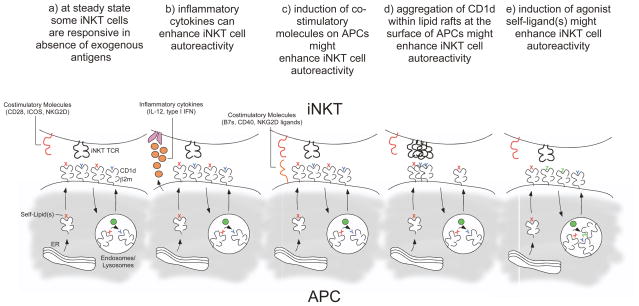

Fig 1. Mechanisms for triggering iNKT cell autoreactivity.

(a) Some iNKT cell hybridomas and clones can readily be activated by CD1d-expressing APCs. During steady state, some self-antigens, depicted as x (in red), are loaded into CD1d molecules in the ER/secretion pathway and other self-antigens, depicted as y (in blue), are loaded into CD1d in the endosomes/lysosomes with the help of lipid transfer proteins46 (depicted as green circles), and both are presented by CD1d molecules at the surface of APCs. (b) A combination of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12, type I interferons) and recognition of self-antigen(s) can trigger an iNKT cell response. (c) Upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules at the surface of activated APCs helps triggering the response of iNKT cells toward self-antigen(s) presented by CD1d. (d) Under certain conditions, CD1d molecules might aggregate within lipid rafts at the surface of the APCs and trigger a response by iNKT cells. (e) Following activation, high affinity agonist self-antigen(s), depicted as z (in green), are generated and loaded onto CD1d in the lysosomes of APCs with the help of lipid transfer proteins46 and replace otherwise weakly stimulatory self-antigen(s), x and y, that are usually presented by CD1d at steady state. Of course, these various possibilities to induce an iNKT cell response against “self” are not mutually exclusive.

The levels of CD1d expression on APCs following stimulation with microbial products might also modulate the activation threshold of iNKT cell autoreactivity. The expression of CD1d molecules have been shown to be upregulated on the surface of macrophages and peritoneal DCs in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines, microbial ligands70, 71, retinoic acid72 and infections with Salmonella enterica73 or Listeria monocytogenes71. However, other studies did not observe increased CD1d expression levels on APCs following exposure to microbial products50.

DC maturation results in increased expression of several adhesion and co-stimulatory molecules that could also contribute to enhanced iNKT cell autoreactivity (Fig 1). Interestingly, requirements for co-stimulation signals appear to be different between iNKT cells purified from different tissues74. This could potentially have important implications for the interpretation of experiments that measure iNKT cell autoreactivity. The tissue from which iNKT cells are isolated, how they are isolated and the type of APCs used to stimulate them probably impact on the observed results. The differences of reactivity between iNKT cell hybridomas generated from different tissues were originally attributed to the expression of different self-antigen–CD1d complexes by different APCs17, 18. Although differences in glycosphingolipid profiling between different APCs (mature DCs versus B cells) exist, no consistent differences in the glycosphingolipid profiles between healthy human donors have been observed75. However, preferential activation of iNKT cells by allogeneic APCs compared to syngenic APCs has been observed75. These results argue that APCs from different donors likely express the same self-antigen(s) loaded onto CD1d but can nevertheless differentially trigger autoreactive iNKT cell responses. This has been attributed to the differential expression of killer immunoglobulin receptor (KIR) by different human iNKT cell lines and clones, the engagement of which by self-HLA class I molecules was suggested to prevent iNKT cell autoreactivity under steady-state conditions75. Dampening iNKT cell autoreactivity through negative signals mediated by inhibitory receptors was also observed in purified hepatic mouse iNKT cells and could be reversed through the upregulation of B7 molecules on APCs76. Together these results suggest that, like NK cells, iNKT cell activation, although dependent on TCR–CD1d interaction, might also be regulated by a balance between stimulatory and inhibitory signals.

Together, the above results suggest that iNKT cells are inherently reactive to self-antigen(s) continually presented by CD1d molecules in the steady state but for most iNKT cells, their activation also requires a non antigen-specific signal that occurs during APC maturation after exposure to microorganisms. This does not preclude that specific endogenous iNKT cell agonist antigen(s) might also be generated following APC stimulation and might replace otherwise weakly stimulatory antigen(s) loaded onto CD1d in immature APCs (Fig 1). Engagement of TLR4, TLR7 and TLR9 has been shown to alter the level of mRNAs encoding several enzymes involved in the biosynthetic pathway of glycosphingolipids, including the enhanced expression of ceramide glucosyltransferase and enzymes implicated in the production of several glycosphingolipids50, 66, 77. Furthermore, APCs exposed to lipid extracts from TLR9-stimulated DCs, but not from naïve DCs, can stimulate liver mononuclear cells (enriched for iNKT cells) when combined with pro-inflammatory cytokines50, 66. Interestingly, in these conditions, only charged (but not neutral) glycosphingolipids, were shown to stimulate mononuclear cells. Mildly basic treatment of the lipid fractions, which destroys diacylglycerols and all lipids (such as phospholipids) except those based on βGluCer, βGalCer and ether lipids, did not reduce mononuclear cell activation. In contrast, digestion of the charged fractions with ceramide glycanase, which releases oligosaccharides from the GluCer-based glycosphingolipids, completely abrogated iNKT cell stimulation66. Together, the results suggested the possibility that charged glycosphingolipids might be synthesized in DCs following TLR stimulation and might be loaded onto CD1d to trigger iNKT cell autoreactivity when presented in conjunction with pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, similar experiments carried out by another group using glycosphingolipids fractions purified from TLR-stimulated DCs and human iNKT cell lines were inconclusive with regards to the nature of glycosphingolipids that could elicit iNKT cell autoreactivity50. Nevertheless, following treatment with TLR ligands, APCs expressed higher levels of CD1d-bound ligands with higher TCR affinity than untreated APCs with identical CD1d expression levels50, suggesting that following TLR signaling, low affinity antigen(s) loaded onto CD1d molecules might be replaced by a higher affinity one(s).

Altogether, these data illustrate that TCR activation of iNKT cells by self APCs can be achieved in several different ways. In some cases, the synthesis of new, still unknown, self-antigen(s) with high affinity for the TCR might be involved, while in others, the recognition of self-antigen(s) already presented by CD1d at steady-state is very likely.

Antigen recognition by the iNKT cell TCR

How do iNKT cell TCRs recognize microbial-derived α-linked glycolipids and some, structurally different, and still elusive, self-antigen(s)? Are TCRs composed of different Vβ chains specific for different self-antigens? What is the role of Vβ CDR3 diversity? Answering these fundamental questions will be key to our understanding of the diversity and nature of the CD1d-restricted self-antigens that are critical to the development and function of iNKT cells, and will help in the design of iNKT cell ligands that will permit us to fine tune iNKT cell function.

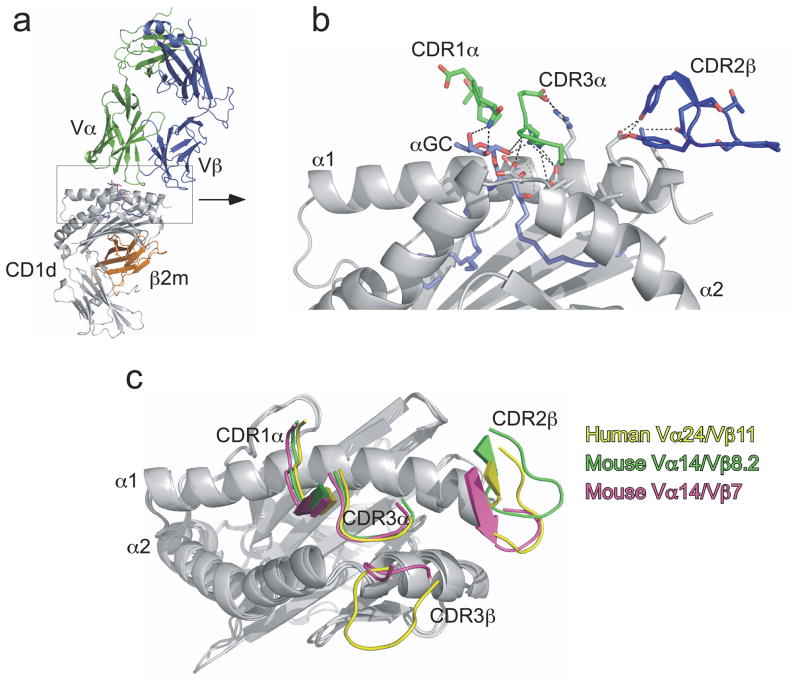

Recent crystallographic and mutational analyses have begun to reveal how the iNKT TCR recognizes glycolipid–CD1d complexes. The crystal structures of one human and two mouse iNKT TCRs in complex with CD1d loaded with the prototypical antigen αGalCer revealed a unique docking that differed from most TCR–peptide–MHC interactions78, 79; the TCR of conventional T cells engages the MHC in an approximate diagonal orientation, whereas the TCR of iNKT cells docks at the very end of, and parallel to, the αGalCer–CD1d complex (see Fig 2a). The recognition of αGalCer–CD1d is mediated by germline-encoded residues located in the CDR1α, CDR3α and CDR2β loops of the TCR (Fig 2b). While this unusual docking of the iNKT cell TCR has so far only been observed with αGalCer–CD1d complexes78, 79, mutational analysis revealed that these TCR ‘hot-spots’ are also required for recognition of structurally different glycolipid antigens such as αGalCer and iGb380, 81. Interestingly, CDR3β, the only hypervariable region of the iNKT TCR, does not make any direct contact with the antigen and instead is found positioned over the α2 helix of CD1d (Fig 2c). Although it remains unclear how this might happen structurally, the CDR3β loop can nevertheless similarly modulate the affinity of the iNKT TCR for various antigen–CD1d complexes80, 82. Because recognition of diverse glycolipid antigens requires the same germline-encoded residues, these observations suggest that the iNKT cell TCR might function as a pattern-recognition receptor and be less ligand-discriminating than conventional TCRs80. In this way, and in contrast to conventional T cells, different iNKT cell clones might have overlapping antigen specificity despite diversity in the TCRβ chain.

Fig 2. Structural overview of αGalCer–CD1d recognition by the iNKT cell TCR.

(a) Vα14–Vβ8.2 NKT cell TCR in complex with αGalCer–mouse CD1d. (b) Magnified view of iNKT cell TCR interaction with αGalCer–mouse CD1d complex. CDR3α mediates multiple contacts between mouse CD1dα– helices and αGalCer. Residues in the CDR2β loop contacts the α1 helix of mouse CD1d. CDR1α interacts solely with αGalCer galactose head group. Other CDR loops were not depicted for purposes of clarity. (c) Superposition of human Vα24-Vβ11 NKT-TCR (yellow) on human CD1d, mouse Vα14–Vβ8.2 (green) on mouse CD1d and mouse Vα14–Vβ7 (pink) on mouse CD1d. CD1d molecules are shown in gray. Only the CDR1α, CDR3α, CDR2β and CDR3β loops of each TCR are depicted for clarity. Note the location of the CDR3β loops over the α2 helix of CD1d. The CDR3β of the Vα14–Vβ8.2 TCR is not depicted as it was mobile and hence could not be resolved on the crystal structure79.

What, then, are the consequences of this overlapping specificity for iNKT cell autoreactivity? If we assume that the iNKT cell TCR recognizes different antigens in a similar manner and that the main difference between ligands lies within the affinity of recognition, then it is possible that various self-antigens can be recognized by iNKT cells as long as they provide sufficient energy to the interaction or do not “get in the way”. If this is indeed the case, then genetic approaches aimed at disrupting specific glycosidases to identify the self-antigen(s) involved in positive selection and autoreactivity of iNKT cells might prove extremely difficult, if not impossible, due to the potential redundancy in antigens, and the disruption of antigen loading in the lysosomal compartment.

A corollary to the previous hypothesis would be that by modifying the iNKT cell TCR so that it can interact optimally with CD1d, it might be possible to increase the affinity of the interaction between the TCR and the ligand–CD1d complexes so that it becomes relatively ligand ‘independent’. If true, this would suggest that unmanipulated iNKT cell TCRs have a suboptimal affinity for CD1d molecules presenting self antigens. In the context of enhanced costimulation or cytokine production by APCs, this affinity might be sufficient to induce the activation of iNKT cells. By manipulating the sequences of Vβ CDR2 and CDR3 loops we recently isolated iNKT cell TCRs that interact with ‘unloaded’ CD1d tetramers82. Hybridomas engineered to express these TCRs are highly autoreactive and respond strongly to CD1d-expressing APCs (T. Mallevaey, J. Scott-Browne, L. Gapin. unpublished observations). These results support the idea that iNKT cell autoreactivity might be due to the recognition of a broad spectrum of self-lipids presented by CD1d with varying agonist activities.

Conclusions

The discovery that some iNKT cells in mice and humans can respond to CD1d-expressing APCs in the absence of exogenously added antigen has shaped our understanding of iNKT cell biology. It has become more and more apparent that the observed autoreactivity of certain iNKT cell hybridomas or clones is a complex phenomenon regulated by many components. The affinity and the expression level of TCRs by some of these clones, their requirement for co-stimulation, the levels of CD1d expression and the need for CD1d aggregation in the plasma membrane of APCs83, and the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines and high-affinity self-antigen(s) presented by CD1d are all likely important parameters that can modulate iNKT cell autoreactivity. Our recent results regarding the iNKT cell TCR specificity argue that several self-antigen(s) can be similarly recognized by different TCRs displaying a range of affinities. This innocuous hypothesis has far reaching implications for iNKT cell biology, as it implies that several self-antigens may be responsible for the positive selection of iNKT cells and the autoreactivity of these cells in peripheral tissues. The next challenge will be to determine which of these self-lipids, when loaded onto CD1d molecules, can bind the iNKT TCR and subsequently what role, if any, these self-lipid(s)–CD1d complexes might have in the thymic selection of iNKT cells and their activation in the periphery.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank members of my lab for helpful discussions and Drs. Philippa Marrack, Mitchell Kronenberg and Dennis Volker for critical reading of the manuscript. I apologize to my colleagues whose works are relevant to iNKT cell autoreactivity but could not be cited due to space constraints. L.G. is supported by grants from the National Institute of Health, USA and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Kronenberg M. Toward an Understanding of NKT Cell Biology: Progress and Paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The Biology of NKT Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nri854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Kaer L, Joyce S. Innate immunity: NKT cells in the spotlight. Curr Biol. 2005;15:429–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–7. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardell S, et al. CD1-restricted CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182:993–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendelac A, et al. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Exley M, Garcia J, Balk SP, Porcelli S. Requirements for CD1d recognition by human invariant Vα24+ CD4−CD8− T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:109–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendiratta SK, et al. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YH, Chiu NM, Mandal M, Wang N, Wang CR. Impaired NK1+ T cell development and early IL-4 production in CD1- deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:459–67. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smiley ST, Kaplan MH, Grusby MJ. Immunoglobulin E production in the absence of interleukin-4-secreting CD1-dependent cells. Science. 1997;275:977–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bendelac A. Positive selection of mouse NK1+ T cells by CD1-expressing cortical thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;182:2091–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanic AK, et al. Defective presentation of the CD1d1-restricted natural Vα14Jα18 NKT lymphocyte antigen caused by β-D-glucosylceramide synthase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1849–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0430327100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu YH, et al. Distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted T cells recognize self-antigens loaded in different cellular compartments. J Exp Med. 1999;189:103–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park SH, Roark JH, Bendelac A. Tissue-specific recognition of mouse CD1 molecules. J Immunol. 1998;160:3128–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brossay L, et al. Mouse CD1-autoreactive T cells have diverse patterns of reactivity to CD1+ targets. J Immunol. 1998;160:3681–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein L, Hinterberger M, Wirnsberger G, Kyewski B. Antigen presentation in the thymus for positive selection and central tolerance induction. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:833–844. doi: 10.1038/nri2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Kearney JF. Autoreactivity by design: innate B and T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:177–86. doi: 10.1038/35105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Andrea A, et al. Neonatal invariant Vα24+ NKT lymphocytes are activated memory cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1544–50. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1544::AID-IMMU1544>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SH, Benlagha K, Lee D, Balish E, Bendelac A. Unaltered phenotype, tissue distribution and function of Vα14+ NKT cells in germ-free mice. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:620–625. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<620::AID-IMMU620>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Der Vliet HJ, et al. Human natural killer T cells acquire a memory-activated phenotype before birth. Blood. 2000;95:2440–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stetson DB, et al. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NKT cells poised for rapid effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1069–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda JL, et al. Mouse Vα14i natural killer T cells are resistant to cytokine polarization in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332805100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renukaradhya GJ, et al. Type I NKT cells protect (and type II NKT cells suppress) the host’s innate antitumor immune response to a B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:5637–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swann JB, et al. Type I natural killer T cells suppress tumors caused by p53 loss in mice. Blood. 2009;113:6382–6385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen NR, Garg S, Brenner MB. Antigen presentation by CD1: Lipids, T cells, and NKT cells in microbial Immunity. Advances in Immunology. 2009;102:1–94. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(09)01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawano T, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Vα14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattner J, et al. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434:525–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinjo Y, et al. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:978–86. doi: 10.1038/ni1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinjo Y, et al. Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature. 2005;434:520–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sriram V, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Brutkiewicz RR. Cell wall glycosphingolipids of Sphingomonas paucimobilis are CD1d-specific ligands for NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1692–701. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zajonc DM, et al. Structure and function of a potent agonist for the semi-invariant natural killer T cell receptor. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:810–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch M, et al. The crystal structure of human CD1d with and without α-galactosylceramide. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:819–26. doi: 10.1038/ni1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barral DC, Brenner MB. CD1 antigen presentation: how it works. Nature Review Immunology. 2007;7:929–941. doi: 10.1038/nri2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox D, et al. Determination of cellular lipids bound to human CD1d molecules. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou D, et al. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306:1786–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joyce S, et al. Natural Ligand of mouse Cd1d1: Cellular glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Science. 1998;279:1541–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan W, Kang SJ, Evans JE, Cresswell P. Natural lipid ligands associated with human CD1d targeted to different subcellular compartments. J Immunol. 2009;182:4784–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gumperz JE, et al. Murine CD1d-restricted T cell recognition of cellular lipids. Immunity. 2000;12:211–21. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rauch J, et al. Structural features of the acyl chain determine self-phospholipid antigen recognition by a CD1d-restricted invariant NKT (iNKT) cell. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47508–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308089200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brigl M, et al. Conserved and heterogeneous lipid antigen specificities of CD1d-restricted NKT cell receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176:3625–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox LM, et al. Recognition of lyso-phospholipids by human natural killer T lymphocytes. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(10):e1000228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiu YH, et al. Multiple defects in antigen presentation and T cell development by mice expressing cytoplasmic tail-truncated CD1d. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:55–60. doi: 10.1038/ni740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou D, et al. Editing of CD1d-bound lipid antigens by endosomal lipid transfer proteins. Science. 2004;303:523–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1092009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang SJ, Cresswell P. Saposins facilitate CD1d-restricted presentation of an exogenous lipid antigen to T cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:175–81. doi: 10.1038/ni1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen X, et al. Distinct endosomal trafficking requirements for presentation of autoantigens and exogenous lipids by human CD1d molecules. J Immunol. 2007;178:6181–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, et al. Immunologic glycosphingolipidomics and NKT cell development in mouse thymus. J Proteome Res. 2009 doi: 10.1021/pr801040h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salio M, et al. Modulation of human natural killer T cell ligands on TLR-mediated antigen-presenting cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20490–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710145104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Godfrey DI, Pellicci DG, Smyth MJ. Immunology. The elusive NKT cell antigen--is the search over? Science. 2004;306:1687–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1106932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gadola SD, et al. Impaired selection of invariant natural killer T cells in diverse mouse models of glycosphingolipid lysosomal storage diseases. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porubsky S, et al. Normal development and function of invariant natural killer T cells in mice with isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5977–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611139104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speak AO, et al. Implications for CD1d-restricted natural killer-like T cell ligands by the restricted presence of isoglobotrihexosylceramide in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5971–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607285104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christiansen D, et al. Humans lack iGb3 due to the absence of functional iGb3-synthase: implications for NKT cell development and transplantation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fagerberg D, et al. Novel Leb-like Helicobacter pylori-binding glycosphingolipid created by the expression of human α-1,3/4-fucosyltransferase in FVB/N mouse stomach. Glycobiology. 2009;19:182–91. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dias BR, et al. identification of iGb3 and iGb4 in melanoma B16F10-Nex2 cells and the iNKT cell-mediated antitumor effect of dendritic cells primed with iGb3. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:116–122. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y, et al. Sensitive detection of isoglobo and globo series tetraglycosylceramides in human thymus by ion trap mass spectrometry. Glycobiology. 2008;18:158–65. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irvine DJ, Purbhoo MA, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature. 2002;419:845–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Purbhoo MA, Irvine DJ, Huppa JB, Davis MM. T cell killing does not require the formation of a stable mature immunological synapse. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:524–30. doi: 10.1038/ni1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parekh VV, et al. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the in vivo response of NKT cells to distinct α- and β-anomeric glycolipids. J Immunol. 2004;173:3693–706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ortaldo JR, et al. Dissociation of NKT stimulation, cytokine induction, and NK activation in vivo by the use of distinct TCR-binding ceramides. J Immunol. 2004;172:943–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slomiany BL, Murty VLN, Liau YH, Slomiany A. Animal glycoglycerolipids. Progress in lipid research. 1987;26:29–51. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(87)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Slomiany BL, Slomiany A, Glass GBJ. Glyceroglucolipids of the human saliva. Eur J Biochem. 1978;84:53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paget C, et al. Activation of invariant NKT cells by toll-like receptor 9-stimulated dendritic cells requires type I interferon and charged glycosphingolipids. Immunity. 2007;27:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tyznik AJ, et al. The mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J Immunol. 2008;181:4452–4456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wesley JD, Tessmer MS, Chaukos D, Brossay L. NK cell-like behavior of Vα14i NK T cells during MCMV infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paget C, et al. Role of invariant NK T lymphocytes in immune responses to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2009;182:1846–1853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sköld M, Xiong X, Illarionov PA, Besra GS, Behar SM. Interplay of cytokines and microbial signals in regulation of CD1d expression and NKT cell activation. J Immunol. 2005;175:3584–3593. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raghuraman G, Geng Y, Wang CR. IFN-β-mediated up-regulation of CD1d in bacteria-infected APCs. J Immunol. 2006;177:7841–7848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szatmari I, et al. PPARγ controls CD1d expression by turning on retinoic acid synthesis in developing human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2351–2362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berntman E, Rolf J, Johansson C, Anderson P, Cardell SL. The role of CD1d-restricted NK T lymphocytes in the immune response to oral infection with Salmonella typhimurium. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2100–2109. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Y, et al. Control of NKT cell differentiation by tissue-specific microenvironments. J Immunol. 2003;171:5913–5920. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patterson S, et al. Human invariant NKT cell display alloreactivity instructed by invariant TCR-CD1d interaction and killer Ig receptor. J Immunol. 2008;181:3268–3276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ikarashi Y, et al. Dendritic Cell Maturation Overrules H-2D-mediated Natural Killer T (NKT) Cell Inhibition. Critical role for B7 in CD1d-dependent NKT cell interferon γ production. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1179–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trottein F, et al. Glycosyltransferase and sulfotransferase gene expression profiles in human monocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages. Glycoconj j. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10719-009-9244-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Borg NA, et al. CD1d-lipid-antigen recognition by the semi-invariant NKT T-cell receptor. Nature. 2007;448:44–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pellicci DG, et al. Differential Vβ8.2 and Vβ7-mediated NKT T-cell receptor recognition of CD1d-α-galactosylceramide. Immunity. 2009;31:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scott Browne J, et al. Germline-encoded recognition of diverse glycolipids by NKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1105–1113. doi: 10.1038/ni1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Florence WC, et al. Adaptability of the semi-invariant natural killer T-cell receptor towards structurally diverse CD1d-restricted ligands. Embo J. 2009;28:3579–3590. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mallevaey T, et al. T cell receptor CDR2β and CDR3β loops collaborate functionally to shape the iNKT cell repertoire. Immunity. 2009;31:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Im JS, et al. Kinetics and cellular site of glycolipid loading control the outcome of natural killer T cell activation. Immunity. 2009;30:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Matsuda JL, Mallevaey T, Scott-Browne J, Gapin L. CD1d-restricted iNKT cells, the ‘Swiss-Army knife’ of the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]