Abstract

We report a high-density self assembling protein microarray that displays thousands of proteins, produced and captured in situ from immobilized cDNA templates. Over 1500 unique cDNAs were tested with > 90% success with nearly all proteins displaying yields within 2 fold of the mean, minimal sample variation and good day to day reproducibility. The displayed proteins revealed selective protein interactions. This method will enable various experimental approaches to study protein function in high throughput.

High density functional protein arrays allow the functional testing of thousands of proteins simultaneously1, 2. A key remaining challenge for producing protein microarrays has been uniting high content (many different proteins) with high density and functionality3. Most approaches rely on expressing and purifying proteins to print on the array surfaces, which have succeeded at displaying both high content and high density1, 2. Significant challenges, however, accompany the use of purified protein for printing microarrays. Variable protein yields result in dynamic ranges that cover several logs, depending on protein size, hydrophobicity, etc. Batch to batch variation may affect reproducibility and the folding and function of some proteins may also be lost during purification, printing, and storage.

To address these concerns, we previously developed a protein microarray method called Nucleic Acid Programmable Array (NAPPA), which allows for functional proteins to be synthesized in situ directly from printed cDNAs just-in-time for assay4. The proteins are translated using a T7-coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate in vitro transcription/translation (IVTT) system. The expressed proteins are captured locally with an antibody to a C-terminal GST tag on each protein. This approach eliminates the need for high throughput protein isolation and ensures that all proteins are produced fresh (i.e., coincident with or minutes before use) for each experiment. Numerous experiments have confirmed that NAPPA produces functional protein5. Other alternate strategies for producing protein microarrays have also been introduced. The Multiple Spotting Technique, MIST, prints an E. coli based IVTT extract directly on top of a printed PCR template6. Another approach employs a variation of ribosome display to immobilize an mRNA-DNA hybrid and express proteins using a cell free translation mix7. A recent approach called DAPA, DNA array to protein array, translates proteins on a cDNA array which then diffuse across a cell free extract-infused membrane to a protein capture surface8. Although encouraging, these strategies have only been tested with relatively small numbers of proteins compared with printing purified proteins and have yet to demonstrate the robust ability to produce the high content needed to justify protein microarrays as a routine proteomics tool.

Here, we describe a next-generation NAPPA method for making fresh protein in situ to produce high content protein microarrays that begin to address many of these important issues. The key printed substrate for NAPPA is purified DNA, which is simpler to prepare, quantify, print and store than protein. In performing optimization experiments, we observed that high quality supercoiled DNA provided the best substrate for cell free protein expression, and that commercial chemistries had insufficient yield and purity for this purpose (data not shown). We therefore investigated the use of a resin derivatized with diamine chemistry, which enabled us to purify high quality DNA efficiently. DNA binds the positively charged diamines at low pH and is eluted when they became neutrally charged under alkaline conditions (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Protocol). One technician can process 5000 samples/week with yields of 18 μg of supercoiled DNA per 1 ml of culture (5–10 fold greater than commercial systems). The DNA is of sufficient quality for use in mammalian cell transfections (data not shown).

We also developed a new printing chemistry that relies on the surprising (and unexplained) ability of bovine serum albumin (BSA) to dramatically improve DNA binding efficiency (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Protocol). BSA and the capture antibody are coupled to the amine-coated glass surface via an activated ester-terminated homobifunctional crosslinker. Using fluorescently labeled DNA, we estimated that 64% of the DNA is captured onto the surface (Supplementary Fig. 1 online).

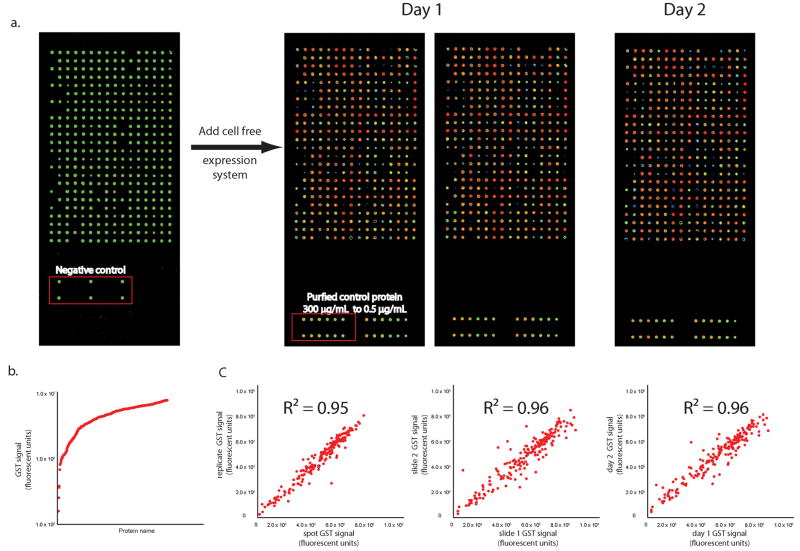

To assess protein yield and reproducibility, we printed a test array of 96 genes, empty expression vector DNA as a negative control, and a concentration series of purified recombinant protein (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). By PicoGreen staining for double stranded DNA (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Protocol), we observed that 97% of the printed samples were detectable (3 standard deviations (SDs) above control features without DNA). Using an anti-GST antibody against the C-terminal GST tag, which confirms full length translation, we detected protein signal for 99% of the 96 printed genes (3 standard deviations (SD) above the signal from non-expressing plasmid) (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Protocol). Compared to the printed recombinant purified GST, the average protein yield was 9 fmoles per feature (4 – 13 fmoles, 10th percentile to 90th percentile). Slide processing for protein display was uniform and reproducible between replicates within an array (R2 = 0.95) and between duplicate arrays (R2 = 0.96) (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Test array. (a) A test array representing 96 unique genes was printed and stained with PicoGreen dye to show DNA binding (left panel). The negative control includes a non expressing plasmid. Test arrays were expressed using T7 transcription and translationally-coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate and the proteins were detected using an anti-GST antibody. Two slides were processed on the same day (middle two panels) and a third slide was processed on a different day (right panel). (b)The amount of protein produced in each feature is shown as a log plot. A 99% success was attained for protein signal, based on a cut off of 3 SD above the negative control (features containing a non expressing plasmid). (c) The raw protein signal from arrays processed on the same day and on different days was compared. Average correlation of signal was >0.95.

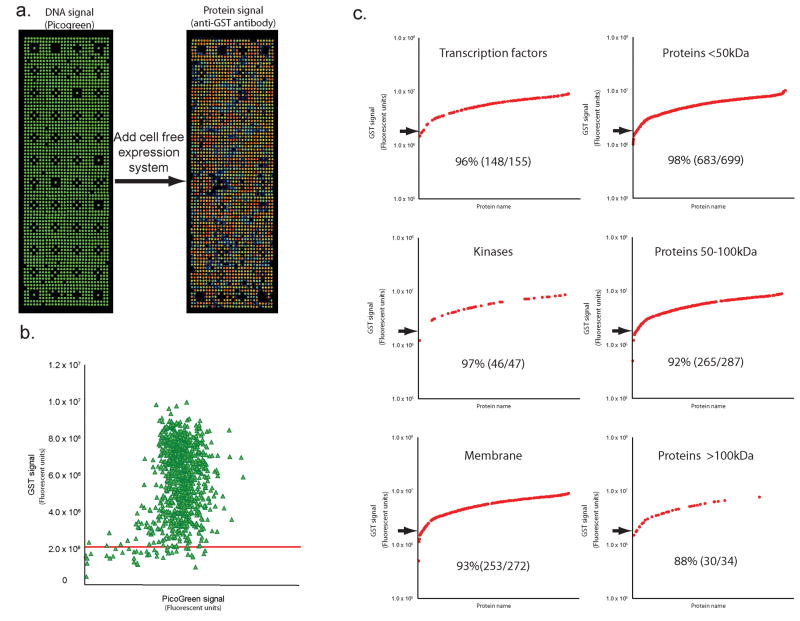

To demonstrate that a variety of proteins can be displayed by this format, we selected 1000 human genes that were colony isolated, full-length sequence verified and readily available through the PlasmID repository9, 10. DNA signal was detected for 99% of the samples (CV = 18%) (Fig. 2a, 2b and Supplementary Table 1). Although we observed a slight variability in protein yield depending on the given DNA amount, 96% (978/1021) of the genes showed readily detectable protein signal. Examining these data by protein class, we observed that kinases (46/47) and transcription factors (148/155) expressed and captured well with success rates of 98% and 95%, respectively (Fig. 2c). Moreover, even membrane proteins, which are typically difficult to produce in heterologous systems, showed good signal for 93% of those tested (253 of 272). The range of protein signal was similar for the various protein families. Predicted protein size had only a mild effect with success rates of 98% (683/699) for <50 kDa, 92% (265/287) for >50 to <100 kDa, and 88% (30/34) for >100 kDa.

Figure 2.

High density array. (a) A high density array with DNA representing a thousand unique genes was printed in duplicate (see Supplementary Table 1 for gene list). The arrays were stained with PicoGreen to show DNA binding (left panel) and anti-GST antibody after expressing the arrays using cell free expression lysate (right panel). (b) The protein signal at every feature is plotted against the amount of DNA captured there. Most of the DNA (98%) and protein signals (92%) were within 2 fold of their respective means. The background (3 SD above the signal from the negative control) is indicated with a line across the graph. (c) The respective success of protein signal was examined by protein class and size and shown as a log plot.

To test for zone effects, we printed the same DNA sample (encoding p53) in 40 features distributed evenly throughout the array and used a p53-specific antibody for detection, which demonstrated an average CV of only 7% (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). To assess the level of signal crosstalk potentially caused by protein diffusion to nearby features, we examined all gene spots neighboring the p53 gene. Immediate neighbors to p53 had signals that were 1.9% of the p53 signal (average of 160 spots), whereas background signal was 0.7% (average of 392 spots that were at least 4 spots [2572 microns] removed from p53). Moreover, the appropriate proteins were displayed as expected, as demonstrated by protein specific antibodies, and revealed little variation (CV = 6%) when independently processed samples were tested.

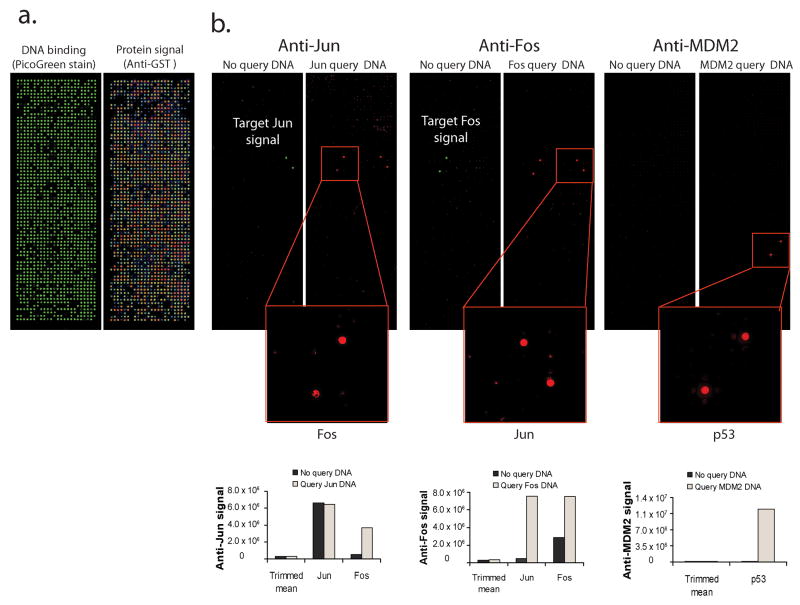

To confirm protein function on high density arrays, we printed an array expressing 647 unique genes in duplicate, including 449 genes that we had not previously tested (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 2). We tested for binary interactions between several well characterized interacting pairs including Jun-Fos (in both directions) and p53-MDM2 (Fig. 3b)11, 12. We co-expressed the query protein along with the arrayed proteins by adding the appropriate cDNA clone (without a GST tag) to the cell free expression lysate5. Following protein expression and washing, the arrays were treated with protein specific antibodies to detect the query protein, revealing the positions where it bound. Using Jun, Fos, and MDM2 as queries we detected selective binding to their appropriate interacting partners. There are no simple tests to confirm protein folding, and function must be tested at the individual protein level. All of the interaction pairs tested here behaved as expected.

Figure 3.

Protein interactions on high density arrays. (a) An array containing DNA for 647 genes was printed (see Supplementary Table 2 for gene list). DNA binding was confirmed by PicoGreen staining and protein signal was confirmed by staining with an anti-GST antibody. (b) Cell free expression lysate was supplemented with query DNA sub-cloned in pANT7_nHA (100–300 ng) expressing query proteins Jun, Fos and MDM2. The binding of the query to the target proteins on the array was detected using the appropriate protein specific antibodies. A control array was processed in each case where no query plasmid was added to the cell free expression lysate. The graph below shows the trimmed mean signal (25%–75%) for each array and the average of the replicate signals for the target protein.

The folding of large multi-domain mammalian proteins often relies on the presence of chaperones and cofactors. Our IVTT-based method utilizes mammalian ribosomal machinery and the presence of chaperones, like hsp90, hsc70 and others, which may encourage folding. The role of chaperones in producing properly folded proteins like kinases, structural proteins, membrane proteins, and even viral proteins in rabbit reticulocyte lysate is well documented.14

Proteins may occur in various activity states depending on co- or post-translational modifications (PTMs). PTMs represent a challenge for all protein microarray formats because proteins produced and purified in heterologous systems may either lack modifications or display unnatural ones. Proteins expressed using the rabbit reticulocyte lysate IVTT system typically lack most PTMs. However, because it is an open system, it is possible to add modifying enzymes, or extracts, such as kinases or canine pancreatic microsomal membranes, to test the effect of PTMs14. In addition some proteins require association with activating partners for function. We have previously shown that multi-protein complexes function in the NAPPA setting.5

The ideal method for producing protein microarrays would evince several important virtues. First, the method must be reliable and reproducible, from sample to sample and array to array. Second, the method should be capable of displaying a broad variety of proteins, insensitive to protein class or size. Third, it should display a high yield of protein per feature, while maintaining a tight range of protein yield from protein to protein. Fourth, the method must be readily executable at large scale and high density. And finally, the method must display functional protein.

Our next generation NAPPA approach, which relies on a new printing chemistry and a new high-throughput, high-yield DNA preparation method, routinely produces 9 fmoles of protein per feature with ~90% success for a broad variety of proteins of different sizes, including membrane proteins and proteins > 100kDa. To our knowledge, this is the first non-protein printing method to produce over a thousand unique proteins on a microarray surface. Importantly, nearly all proteins were displayed within a narrow range of protein levels; 92% of displayed proteins were within 2 fold of the mean. This limited variation may be due to the saturation of the capture sites on the array by the expressed target. The method was highly reproducible from array to array and sample to sample (CV = 6%), which compares favorably with that reported for DNA microarray chemistries where CV’s range from 20–40% 13. This is particularly important considering that NAPPA entails not only printing cDNA but also transcription, translation, and protein capture. The ability to array proteins at high density will be well suited for testing protein-protein interactions, screening for enzyme substrates, and measuring selectivity of small molecule drug binding.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figure 1 Optimization of DNA binding

Supplementary figure 2 Purified protein spotting

Supplementary figure 3 Signal variation

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Supplementary Protocols

Supplementary Table 1 List of genes printed in figure 2

Supplementary Table 2 List of genes printed in figure 3

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Janice Williamson and Mauricio Fernandez for their help with the robotics and Dongmei Zhu, and Rick Boyce for the development of the DNA normalization tool. This study was supported by the Early Detection Research Network (EDRN, NCI, Grant 5U01CA117374-02) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID, Contract HHSN2332200400053C).

References

- 1.MacBeath G, Schreiber S. Science. 2000;289:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu H, et al. Science. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun P, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2654–2659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042684199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramachandran N, LaBaer J. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandran N, et al. Science. 2004;305:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1097639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angenendt P, Kreutzberger J, Glokler J, Hoheisel JD. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1658–1666. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tao SC, Zhu H. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1253–1254. doi: 10.1038/nbt1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He M, et al. Nature methods. 2008;5:175–177. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy T, et al. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rolfs A, et al. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutell JM, Hart DJ, Godber BL, Kozlowski RZ, Blackburn JM. Proteomics. 2004;4:1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman JR, Keating AE. Science. 2003;300:2097–2101. doi: 10.1126/science.1084648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rickman DS, Herbert CJ, Aggerbeck LP. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:e109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arduengo M, Schenborn E, Hurst R. Cell free protein expression. Landes Bioscience; Austin: 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figure 1 Optimization of DNA binding

Supplementary figure 2 Purified protein spotting

Supplementary figure 3 Signal variation

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Supplementary Protocols

Supplementary Table 1 List of genes printed in figure 2

Supplementary Table 2 List of genes printed in figure 3