Abstract

Despite improvements in interventions of acute coronary syndromes, primary reperfusion therapies restoring blood flow to ischemic myocardium leads to the activation of signaling cascades that induce cardiomyocyte cell death. These signaling cascades, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways, activate cardiomyocyte death in response to both ischemia and reperfusion. We have previously identified muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF1) as a cardiac-specific protein that regulates cardiomyocyte mass through its ubiquitin ligase activity, acting to degrade sarcomeric proteins and inhibit transcription factors involved in cardiac hypertrophy signaling. To determine MuRF1's role in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, cardiomyocytes in culture and intact hearts were challenged with I/R injury in the presence and absence of MuRF1. We found that MuRF1 is cardioprotective, in part, by its ability to prevent cell death by inhibiting Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling. MuRF1 specifically targets JNK's proximal downstream target, activated phospho-c-Jun, for degradation by the proteasome, effectively inhibiting downstream signaling and the induction of cell death. MuRF1's inhibitory affects on JNK signaling through its ubiquitin proteasome-dependent degradation of activated c-Jun is the first description of a cardiac ubiquitin ligase inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. MuRF1's cardioprotection in I/R injury is attenuated in the presence of pharmacologic JNK inhibition in vivo, suggesting a prominent role of MuRF1's regulation of c-Jun in the intact heart.

Factors that occlude the coronary arteries, such as thrombi and acute alterations in atherosclerotic plaques, result in myocardial ischemia. Advances in therapeutic interventions that restore the blocked coronary have had profound effects in limiting the size of the infarct by reducing the amount of frank necrosis in proportion to how quickly reperfusion takes place.1 Because reperfusion itself has deleterious effects, including the activation of inflammation and the induction of apoptosis, it has driven intensive study to identify mechanisms that could be targeted to reduce the amount of damage due to therapeutic reperfusion.

The signaling pathways in myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury are complex, redundant, and have not been fully elucidated. Several pro-apoptotic signaling pathways have been described in cardiomyocytes. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, including the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) and the p38 MAPK. The JNK signaling pathway in particular is activated during ischemia and/or reperfusion,2–8 leading to the induction of apoptosis during I/R injury.6,9 These findings led to the hypothesis that inhibiting JNK activity would reduce apoptosis after I/R injury. Several studies have provided evidence to prove this concept true by using a nonpeptide ATP competitive JNK inhibitor10 and a peptide inhibitor of c-Jun.11 In these studies, inhibition of JNK or the more specific inhibition of c-Jun was found to be cardioprotective in vivo.

We recently found that muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF1) blocks pathological cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting pro-hypertrophic signaling by directly binding and inhibiting the transcription factor serum response factor.12 We have also found that MuRF1 is necessary for the development of cardiac atrophy and cardiac hypertrophy reversal.13 MuRF1 is a cardiac ubiquitin ligase localized to the cytoplasm14 and the M-line of the sarcomere,15 where it targets local proteins such as troponin I, β/slow myosin heavy chain, and myosin binding protein-C for degradation.16–18 This degradation occurs through the coordinated placement of polyubiquitin chains on recognized substrates, which are subsequently degraded by the proteasome.19 MuRF1 exerts its regulation of a number of cellular processes through its ubiquitin ligase activity and is involved in monitoring the protein quality control of the cardiomyocyte.20 While previous studies have identified several good candidates using in vitro approaches, the identification of the physiological in vivo targets of MuRF1 is still ongoing.

Activation of MAPK signaling pathways occurs in response to increased oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, and stretch, including focal adhesion kinase and stretch activated channels in cardiac myocytes.21 In the present study, we identify a role of cardiac MuRF1 in the protection against I/R injury by inhibiting JNK signaling by its specific interaction with and subsequent degradation of JNK's proximal effector c-Jun. MuRF1 does this by preferentially recognizing and ubiquitinating the activated (phosphorylated) c-Jun, which is targeted for degradation by the 26S proteasome to effectively inhibit downstream signaling. With use of in vivo models of ischemia reperfusion injury, we identify that increasing MuRF1 inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by I/R injury by blocking JNK signaling through c-Jun, resulting in significant cardioprotection. These findings represent a novel mechanism by which the cardiac ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 coordinates the ubiquitin proteasome system to regulate the JNK signaling pathway in response to stress-mediated stimuli.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The MuRF1 Tg+ mice used in this study were previously described.22 All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care Advisory Committee and were in compliance with the rules governing animal use as published by the National Institutes of Health.

Plasmids, Antibodies, Chemicals, and Recombinant Proteins

The full-length and truncated forms of MuRF1 and c-Jun were generated by PCR and subcloned into mammalian expression plasmid pCMV-TB3, pcDNA3.1, pEGFP-C1, or glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein expression plasmid pGEX-KG as previously described.14,16 A luciferase reporter plasmid, AP1-Luciferase reporter, was from BD Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, generously provided by Dr. Chiwing Chow). MuRF1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) was generated using BD knockout RNA interference and cloned into pSIREN vector as previously described.14 The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: anti-Flag (M2, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); anti-HA (12CA5; Roche Diagnostics Corp., Basel, Switzerland); anti-GST (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ); anti-Myc (9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); anti-ubiquitin, anti-His, and anti-β-actin (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA); anti-JNK, anti-phospho-JNK, anti-c-Jun, and anti-phospho-c-Jun (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); and anti-mouse–conjugated and anti-rabbit–conjugated antibodies (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Cycloheximide, MG132, E1, Ubc5C, and ubiquitin were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Luciferase Assays

HEK293T and the H9C2 cardiomyocyte cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured as previously described.23 Cycloheximide and MG132 were added at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml and 10 μmol/L, respectively. The luciferase reporter constructs were co-transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corp.) with expression vectors carrying AP-1-Luc, c-Jun, MuRF-1 WT, and mutants into HEK293T cells or with MuRF1 siRNAs into H9C2 cells, and luciferase activity was measured as previously described.23 The data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments run in duplicate and normalized for β-gal activity.

Simulated I/R

Cells were transduced after 24 hours with adenovirus and then challenged with a simulated I/R (SI/R) as previously reported.24 Briefly, cells were placed in an “ischemia buffer” for 60 minutes in a 5% CO2 to 2% O2 incubator (37°C) containing 118 mmol/L NaCl, 24 mmol/L NaHCO3, 1.0 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 2.5 mmol/L CaCl2-2H2O, 1.2 mmol/L MgCl2, 20 mmol/L sodium lactate, 16 mmol/L KCl, and 10 mmol/L 2-deoxyglucose (pH adjusted to 6.2). After 60 minutes, reperfusion was obtained by replacing the ischemic buffer with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 5% CO2 incubator with room air.

Determination of Cell Death by Trypan Blue, DNA Fragmentation, TUNEL Staining, and Cleaved Caspase 3

Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion assay and by flow cytometry using the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Corp.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Apoptosis Detection System, fluorescein, catalog #G3250, Promega, Madison, WI). Western blot analysis of apoptosis was performed by using an anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, Cat, #9661), which recognizes the endogenous levels of the large fragment (17/19 kDa) of activated caspase 3 resulting from cleavage adjacent to Asp175 as previously described.24–26

MAPK Inhibitors

The MAPK inhibitors U0126, SB203580, and SP600125 were used as previously described.27–30

Administration of JNK Inhibitor in Vivo

The JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Anthra[1,9-cd]pyrazol-6(2H)-one; 1,9-pyrazoloanthrone; SAPK Inhibitor II) was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, product #420119). SP600125 (6 mg/kg dose dissolved in 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide) was administered intraperitoneally to four wild-type and three MuRF1 Tg+ mice 2 hours before left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery ligation and reperfusion as previously described.31

Immunoprecipitation, GST Pull-Down, and Western Blot Assays

Immunoprecipitations and Western blot analysis was performed as previously described.23 Briefly, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with Myc-MuRF1 and Flag-c-Jun expression vectors using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics Corp.). Tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated for 2 hours at 4°C with either anti-Myc or anti-FLAG using protein A/G agarose beads, washed, and analyzed by immunoblotting as previously described.23 GST pull-down assays were performed as described.23 Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with a Flag-c-Jun expression plasmid for 24 hours and then lysed for 30 minutes and pre-cleared with GST beads for 1 hour. Lysates were then incubated with either GST or GST-MuRF1 fusion proteins for 1 hour at 4°C. The bound glutathione-Sepharose beads were then washed four times with lysis buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting as previously described.23

Immunofluorescence

H9C2 cells were cultured and examined for MuRF1 or c-Jun expression by using immunostaining with anti-MuRF1 or anti-c-Jun antibodies, respectively, and appropriate secondary antibodies. Samples were observed using confocal microscopy (TCS SP2 laser-scanning spectral confocal system; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assays

To assess ubiquitination in vivo, HEK293T cells were transfected with expression vectors containing His-Ub, Flag-c-Jun, and Myc-MuRF-1 using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics Corp.). Protein lysates were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by Western blot using appropriate antibodies as previously described.23

Nickel-Agarose Chromatography

HEK293T cells were transfected with His-Ub, Flag-c-Jun, and Myc-MuRF-1 WT or RING deletion mutant Myc-MuRF1 (MuRF1 Δ RING) expression plasmids and lysed in Ni-agarose lysis buffer [50 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 300 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L imidazole, 0.05% Tween 20, 10 mmol/L N-ethylmaleimide, and Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics Corp.)]. His-ubiquitin-conjugated proteins were purified by nickel chromatography and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-His or anti-Flag antibody as previously described.32

In Vitro Ubiquitination Reactions

Ubiquitination reactions in vitro were performed as previously described.23 Briefly, the reaction mixture (final volume 30 μl) containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mmol/L MgCl, 2 mmol/L NaF, 10 nmol/L okadaic acid, 2 mmol/L ATP, 0.6 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 60 ng of E1, 600 ng of Ubc5C, 1 μg of purified GST–MuRF1 Wt or RING deletion mutant, 1 μg purified c-Jun, and 10 μg of ubiquitin was incubated at 30°C for 2 hours and terminated by boiling in SDS–sample buffer containing 0.1 M dithiothreitol for 5 minutes. Samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Western immunoblot.

Isolated Heart Analysis/Global I/R Injury

Hearts from MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-type mice were isolated and perfused as previously described.33–35 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and heparinized. Hearts were then quickly removed and placed in ice-cold buffer, followed by aortic cannulation for retrograde perfusion with a phosphate-free Krebs-Henseleit buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, K3753) supplemented with calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cardiac function was followed using a balloon placed in the left ventricle, monitored using a pressure transducer, and analyzed using EverBeat system acquisition software (Mouse Specifics, Inc., Boston, MA). The hearts were stabilized for a period of at least 20 minutes, followed by a 15-minute period of no-flow ischemia, followed by a 20-minute period of reperfusion. Recovery of function was determined as a percentage of pre-ischemic function.

LAD I/R Injury/Echocardiography

I/R injury was performed by ligation of the LAD coronary artery for 30 minutes, followed by 24 hours of reperfusion. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (45 mg/kg), intubated, and placed on a ventilator (tidal volume 200 μl, respiratory rate 120/minute, 100% oxygen). The chest cavity was opened by an incision of the left fourth intercostal space, and the pericardial sac was removed to visualize the LAD coronary artery. A 7-0 silk suture was passed underneath the LAD artery ∼1 to 2 mm below the left auricle and tied around a 1-mm length of polyethylene tubing (OD = 0.61 mm; Intramedic PE-10, Clay Adams, Parsippany, NJ) to produce myocardial blanching and ECG ST-segment elevation. After 30 minutes, blood flow was restored and the chest wall was then closed. Postoperatively, a dose of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was given and the mice were allowed to recover at 37°C. Echocardiography on mice was performed at baseline and after 24 hours of reperfusion on a VisualSonics Vevo 770 ultrasound biomicroscopy system as previously described.12

Real-Time PCR Analysis of MuRF1 Family Protein Regulation

Total RNA was isolated from heart using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corp.) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Gene expression studies were performed by a two-step reaction to determine mRNA expression as previously described.12,13 The PCR reaction mix included 1 μl of mouse-specific TaqMan probes for MuRF1 (Mm01188690_m1), MuRF2 (Mm 01292965_m1), MuRF3 (Mm 00491308_m1), or 18S (Hs99999901_s1) in triplicate (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Rat MuRF1 (Rn00590197_m1), MuRF2 (Rn01493339_m1), and MuRF3 (Rn01470046_m1) were assayed in H9C2 cells and normalized to 18S in a similar manner. The relative expression of mRNA was determined using 18S as an internal sample loading control.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were evaluated for statistical significance using Student's t-test. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

MuRF1 Regulates I/R-Induced Cell Death and Decreases Phospho-c-Jun Levels in Cardiomyocytes

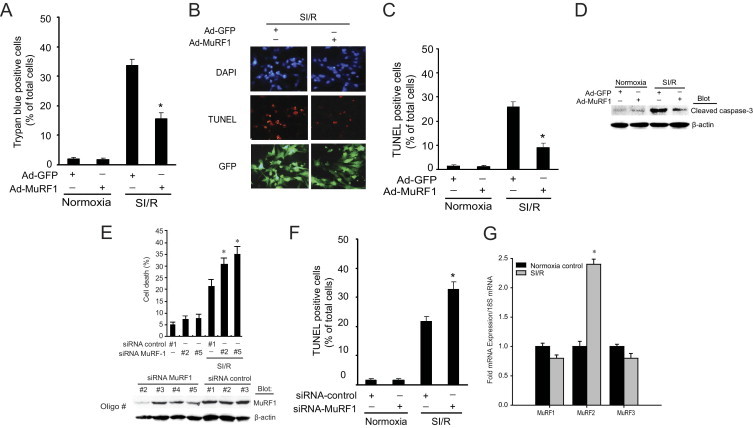

We used an adenovirus-dependent gene delivery system14 to investigate the effects of MuRF1 on H9C2 cardiomyocyte viability after SI/R injury. Challenging cardiomyocytes with a 1-hour simulated ischemia followed by a 24-hour reperfusion induced an approximately 35% decrease in control cell viability (Figure 1A). With increased MuRF1 expression, cardiomyocytes were significantly protected from SI/R challenge with less than a 20% decrease in cell viability. SI/R challenge of H9C2 cells resulted in a parallel increase in apoptosis determined by TUNEL staining (Figure 1, B and C) and cleaved caspase-3 activation (Figure 1D). Increased MuRF1 attenuates SI/R-induced TUNEL-positive cells and cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 1, B–D), indicating its ability to inhibit apoptotic cell death. Conversely, we found that knocking down MuRF1 expression in cardiomyocytes with siRNA significantly enhanced DNA fragmentation after SI/R challenge (Figure 1E) and TUNEL positive cells (Figure 1F), which is indicative of MuRF1's role in inhibiting apoptosis. MuRF2 mRNA expression, but not MuRF1 and MuRF3 mRNA expression, was significantly increased after 24 hours of SI/R (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

MuRF1 protects against I/R injury–induced cell death. A: Increasing MuRF1 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes using adenovirus protects against cell death after challenge with 1-hour simulated ischemia (SI) followed by a 24-hour reperfusion (R), determined by trypan blue exclusion. B: The number of apoptotic H9C2 cells observed by TUNEL assay after SI/R is significantly less with increased MuRF1 expression as shown in these representative fields. C: Quantitative analysis of TUNEL-positive cells was from three independent experiments (120 cells counted per experiment). D: Activated (cleaved) caspase-3 was increased in response to SI/R. Increasing MuRF1 blunted the amount of cleaved caspase-3 determined by Western immunoblot. E: Cardiomyocytes with decreased MuRF1 after 36 hours of siRNA transfection determined by immunoblot (below) have an enhanced cell death after SI/R (top) determined by DNA fragmentation analysis by flow cytometry. F: An increase in TUNEL-positive cells occurs after cardiomyocytes were infected with adenovirus siRNA-control or siRNA-MuRF1 at 50 multiplicity of infection for 24 hours, and then treated with normoxia or SI/R for 24 hours. Quantitative analysis was performed as described in C. G: Quantitative analysis of MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3mRNA expression by RT-PCR in H9C2 cells after SI/R. Results are expressed as means ± SEM, *P < 0.01 versus Ad-GFP or siRNA-control.

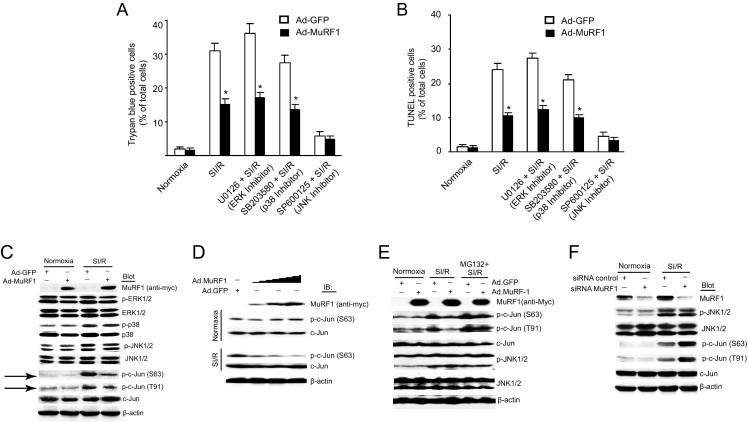

We first determined which MAPK signaling pathways were important in the MuRF1-mediated protection from cell death in cardiomyocytes induced by SI/R using inhibitors that targeted extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, or JNK. Control H9C2 cardiomyocytes (Ad.GFP) and cells with increased MuRF1 levels (Ad.MuRF1) were challenged to SI/R in the presence and absence of inhibitors of ERK, p38, and JNK (Figure 2). By both trypan blue exclusion (Figure 2A) and TUNEL analysis of cells (Figure 2B), SI/R was shown to enhance cell death by mainly apoptosis (SI/R). Cells receiving the ERK and p38 inhibitors (U0126 and SB203580, respectively) underwent the same amount of cell death as did SI/R controls, suggesting that these signaling pathways did not play a significant role in the SI/R-induced cell death or MuRF1's cardioprotection (Figure 2, A and B). When a JNK inhibitor (SP600125) was given in parallel studies, significantly less cell death occurred after SI/R in control cells (Ad.GFP) and cells with increased MuRF1. This finding suggests that JNK plays a prominent role in cardiomyocyte SI/R in our model and may be the pathway that MuRF1 regulates to inhibit SI/R-induced cell death. Additional evidence that MuRF1 acted on the JNK signaling pathway but not the p38 or ERK signaling pathways comes from Western blot analysis of the ERK, p38, and JNK pathways after SI/R in the presence of increased MuRF1 (Figure 2C). The SI/R induced increases in activated c-Jun (phospho-c-Jun S63 and T91, both necessary for activity).36,37 The SI/R-induced increase in phosphorylation c-Jun (p-c-Jun) was attenuated in the presence of increased MuRF1 (Figure 2C, arrows), whereas the increased phospho-p38 was unaffected. This finding confirmed the inhibitor studies that implicated JNK signaling in regulating SI/R-induced cardiomyocyte cell death. Two possible reasons for this decreased c-Jun signaling are that signaling upstream of c-Jun was being inhibited by MuRF1 or c-Jun itself was being directly targeted. To delineate where MuRF1 was acting on JNK signaling, we investigated the activation of JNK (phospho-JNK), which directly phosphorylates c-Jun in the JNK signaling pathway. By Western blot analysis, increased phospho-JNK induced by SI/R was not affected by increased MuRF1 (Figure 2C). Because JNK's most proximal effector c-Jun was decreased, this finding suggested that MuRF1 inhibited JNK signaling at the level of c-Jun during SI/R in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2.

MuRF1 protects against ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibiting c-Jun but not the ERK or p38 signaling pathways in a proteasome-dependent manner. A and B: MuRF1 protects against cell death by inhibiting JNK signaling. H9C2 cardiomyocytes were infected with 50 multiplicity of infection Ad-GFP or Ad-MuRF1 for 24 hours pretreated with U0126 (MAP kinase/Erk kinase inhibitor, inhibiting ERK1/2, 10 μmol/L), SB203580 (p38 inhibitor, 10 μmol/L), or SP600125 (JNK inhibitor, 10 μmol/L) before 30 minutes of simulated hypoxia and 24 hours reperfusion or normoxia. Cell death was determined by trypan blue exclusion (A) and by TUNEL staining (B) and demonstrated that SI/R cell death was mediated primarily by the JNK signaling pathway. C: H9C2 cardiomyocytes were transduced with 50 multiplicity of infection Ad-GFP or Ad-MuRF1, and the effects on MAPK signaling pathways were determined. By Western immunoblot, total and phospho-ERK1/2, total and phospho-p38, total and phospho-JNK1/2, total and phospho-c-Jun (Ser63 or Thr91), and Myc-MuRF1 were determined by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. Only phospho-c-Jun (Ser63 and Thr91) levels were significantly decreased when MuRF1 expression is increased, indicating that MuRF1 exerts its regulation of cell death by regulating JNK signaling. D: Cardiomyocytes with increasing MuRF1 challenged with SI/R have a blunted or decreased phospho-c-Jun response. E: Parallel studies using the proteasome inhibitor MG132 6 hours before harvest demonstrated that the blunted phospho-c-Jun response is dependent on proteasome degradation. F: Decreasing MuRF1 using siRNA conversely enhances phospho-c-Jun after SI/R challenge in cardiomyocytes. Results are expressed as means ± SEM, *P < 0.01 versus Ad-GFP. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

Recently, MuRF1 has been identified as a cardiac-specific ubiquitin ligase, targeting substrates for degradation by the addition of polyubiquitin chains and subsequent degradation by the proteasome.14,16,23 We then explored the possibility that MuRF1 regulated c-Jun by mediating ubiquitin-dependent degradation. By degrading c-Jun, MuRF1 might act to inhibit apoptosis by preventing the interaction of phospho-c-Jun with c-Fos to make up the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor to induce apoptosis.38 To begin to delineate this relationship, cardiomyocytes were challenged with SI/R with increasing levels of MuRF1, and phospho-c-Jun was followed (Figure 2D) in the presence and absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 2E). Increasing MuRF1 results in a dose-dependent decrease in phospho-c-Jun in SI/R but not in normoxic conditions (Figure 2D), suggesting that MuRF1 degrades the activated form of c-Jun. To further delineate how MuRF1 may decrease the activated (phosphorylated) c-Jun, we added the proteasome inhibitor MG132. When MG132 is added to cardiomyocytes after SI/R, increased MuRF1 no longer decreases the activated forms of c-Jun (p-c-Jun S64 and T91) (Figure 2E). This finding suggests that the degradation of c-Jun occurs in a proteasome-dependent manner, consistent with MuRF1's role as a ubiquitin ligase. To determine whether MuRF1 is essential in dampening the pathophysiologic increases in phospho-c-Jun induced by SI/R, we knocked down MuRF1 with siRNA in cardiomyocytes and determined how SI/R stimulated c-Jun activation (Figure 2F). Without endogenous MuRF1 to regulate the increases in phospho-c-Jun (both S64 and T91), phospho-c-Jun levels were exaggerated compared with siRNA controls after SI/R (Figure 2F), implicating a role of endogenous MuRF1s in regulating SI/R-induced increases in p-c-Jun stimulated by SI/R.

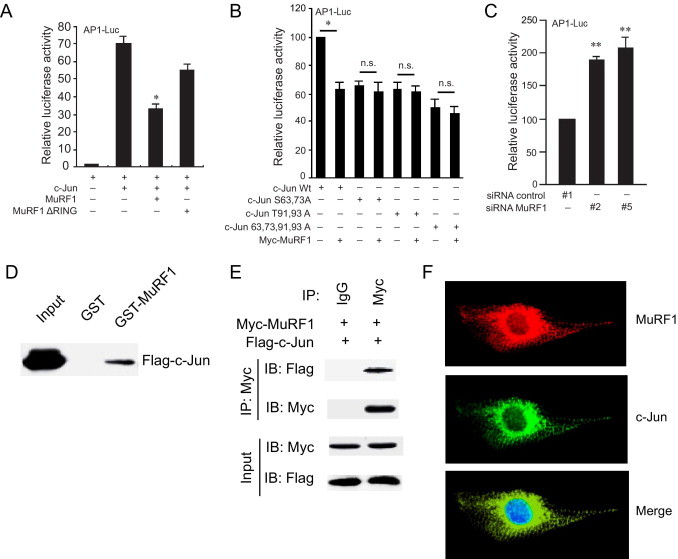

MuRF1 Binds to c-Jun to Inhibit Its Cooperative Transactivation of the AP-1 Transcription Factor in a Ubiquitin Ligase-Dependent Manner

The AP-1 family of proteins represent sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors formed by homo- and hetero-dimers of jun (c-jun, junB, and junD) and fos (c-fos, fra-1, and fra-2) proteins.39 To determine how MuRF1's attenuation of phospho-c-Jun affects AP-1 activity, the transcriptional activation of AP-1 was determined in the presence and absence of increased MuRF1 expression (Figure 3A). Increasing MuRF1 expression significantly decreased activation of the AP-1 response element in cells transfected with AP-1 response element–luciferase reporter constructs. Previous studies found that MuRF1's RING finger domain is the region with ubiquitin ligase activity.16,40 One possible mechanism by which MuRF1 might inhibit AP-1 activity is through its interaction and ubiquitination of c-Jun. To test this possibility, we determined how MuRF1 that was missing its RING finger domain affected AP-1 activity. MuRF1 that lacked the RING finger domain (with ubiquitin ligase activity) did not significantly inhibit AP-1 activity (Figure 3A), whereas MuRF1 with its intact RING finger intact did. This finding indicates the dependence of MuRF1's ubiquitin ligase activity on its ability to inhibit AP-1 activity. We also found that activation of the AP-1 construct depended on c-Jun's phosphorylation of S63, S73, T91, and T93; MuRF1's attenuation of c-Jun activity similarly relied on c-Jun's phosphorylation as determined by AP-1 activity assays using c-Jun phosphorylation mutant constructs (Figure 3B). In parallel experiments, AP-1 transcriptional activation was determined after endogenous MuRF1 was decreased using siRNA (Figure 3C). Consistent with its role as a ubiquitin ligase recognizing and inhibiting AP-1 activity [specifically activated (phospho-)c-Jun], decreasing endogenous MuRF1 resulted in the enhanced activation of AP-1 activity in cardiomyocytes (Figure 3C). This finding suggests that endogenous MuRF1 plays a role in regulating endogenous AP-1 activity in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3.

MuRF1 directly interacts with c-Jun to inhibit transcriptional activity. A: To assess the role of MuRF1 on phospho-c-Jun transcriptional activity, HEK293T cells were transfected with luciferase plasmids driven by the AP-1 promoter as indicated. The ubiquitin ligase activity of MuRF1, found in the RING motif, was necessary for the inhibition of AP-1 activity. B: To assess which c-Jun phosphorylation sites were necessary for MuRF1's inhibition of AP-1 activity, wild-type c-Jun and c-Jun mutants were co-transfected in HEK293T cells with the AP-1 luciferase reporter with and without MuRF1. Luciferase activity was determined after 24 hours. C: To assess how decreasing endogenous MuRF1 affects AP-1 activity, H9C2 cardiomyocytes were co-transfected with AP-1 luciferase, siRNA oligo controls, siRNA MuRF1 oligos, and luciferase activity was determined after 36 hours. D: To determine whether MuRF1 interacts directly with c-Jun to inhibit its activity, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-cJun and pulled down by GST-MuRF1 or GST followed by immunoblot for c-Jun. E: This direct interaction was confirmed by specific immunoprecipitation of myc-MuRF1 after co-transfection of myc-MuRF1 and FLAG-c-Jun plasmids in HEK293T cells by immunoblot. F: The co-localization of MuRF1 and c-Jun in cardiomyocytes was identified with use of confocal microscopy and immunofluorescent staining of MuRF1 (anti-MuRF1/red), c-Jun (anti-c-Jun/green), and nuclei (DAPI/blue). *P < 0.01 versus wild-type c-Jun alone. **P < 0.01 versus siRNA control. n.s. indicates not significant.

To build on the evidence that MuRF1 attenuates phospho-c-Jun through its ubiquitin ligase activity, we next determined whether MuRF1 interacted with c-Jun to affect its activity using GST-MuRF1 pull-down and MuRF1 immunoprecipitation (Figure 3, D and E). When cell lysates from cells transfected with Flag-c-Jun plasmids are run over a GST-MuRF1 column, MuRF1 is able to specifically pull down c-Jun (Figure 3D). Immunoprecipitation of MuRF1 similarly pulls down c-Jun specifically in cells transfected with c-Jun and MuRF1 expression constructs (Figure 3E), indicating the specificity of the interaction between c-Jun and MuRF1. The interaction of these two proteins in cardiomyocytes was confirmed by co-localizing MuRF1 and c-Jun in the cytoplasm (ie, in a distinctly non-nuclear distribution) of cardiomyocytes using confocal immunofluorescence (Figure 3F).

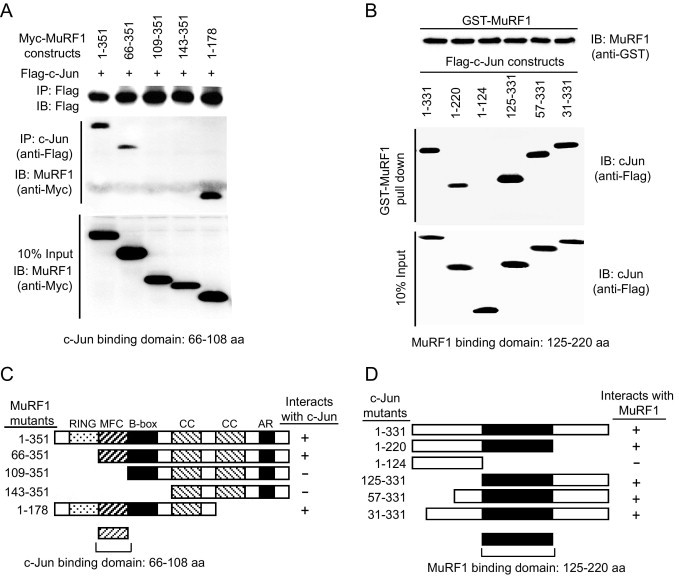

MuRF1's MuRF Family Conserved Region Interacts with c-Jun

When JNK phosphorylates (activates) c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun binds fos proteins to act as the transcription factor AP-1 and induce downstream effectors such as apoptosis in I/R injury.39,41–45 Because we determined that MuRF1 interacts with the c-Jun subunit of the AP-1 complex (made up of jun and fos), we further characterized the regions in which MuRF1 and c-Jun interacted with each other through the use of deletion constructs (Figure 4). This characterization was done by transfecting plasmids with myc-tagged truncated MuRF1 constructs and full-length c-Jun into HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitating c-Jun to determine the MuRF1 regions necessary for binding (Figure 4A). Using deletion constructs, we mapped the sites that MuRF1 needs to interact with c-Jun to a 42–amino acid sequence immediately adjacent to the RING finger region in MuRF1 (Figure 4, A and C). This 42–amino acid MuRF family conserved (MFC) region is found in all 3 MuRF proteins—MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3.46 Using MuRF1 pull-down assays, we also identified the region of c-Jun that was necessary for MuRF1 to interact. c-Jun deletion constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells and lysates were applied to a GST-MuRF1 column. By immunoblotting the proteins eluted off the GST-MuRF1, we were able to identify the specific regions of c-Jun necessary for it to bind MuRF1 (Figure 4B). A 95 amino acid region of c-Jun (125-220 a.a.) was identified as necessary for it to interact with MuRF1 (Figure 4, B and D). While we identified that MuRF1's MFC domain interacts with c-Jun's 125-220 a.a. region, these studies do not exclude the possibility that additional MuRF1 and c-Jun sequences play a role in their interaction.

Figure 4.

MuRF1 binds c-Jun through its MFC domain found in all MuRF family proteins. A: The determination of the MuRF1 region that interacted with c-Jun was made by co-transfecting FLAG-c-Jun and myc-tagged MuRF1 deletion mutants and following interactions by immunoprecipitation of c-Jun. B: The region of c-Jun that is necessary to bind MuRF1 was determined using GST-MuRF1 fusion protein to pull down c-Jun deletion constructs. C: The schematic representation of how MuRF1 deletion constructs interacted with c-Jun shows the essential nature of the MFC region for MurF1 to bind c-Jun. D: The schematic representation of pull-down assays demonstrate that the 125-220–amino acid region of c-Jun is necessary for MuRF1 to interact with c-Jun.

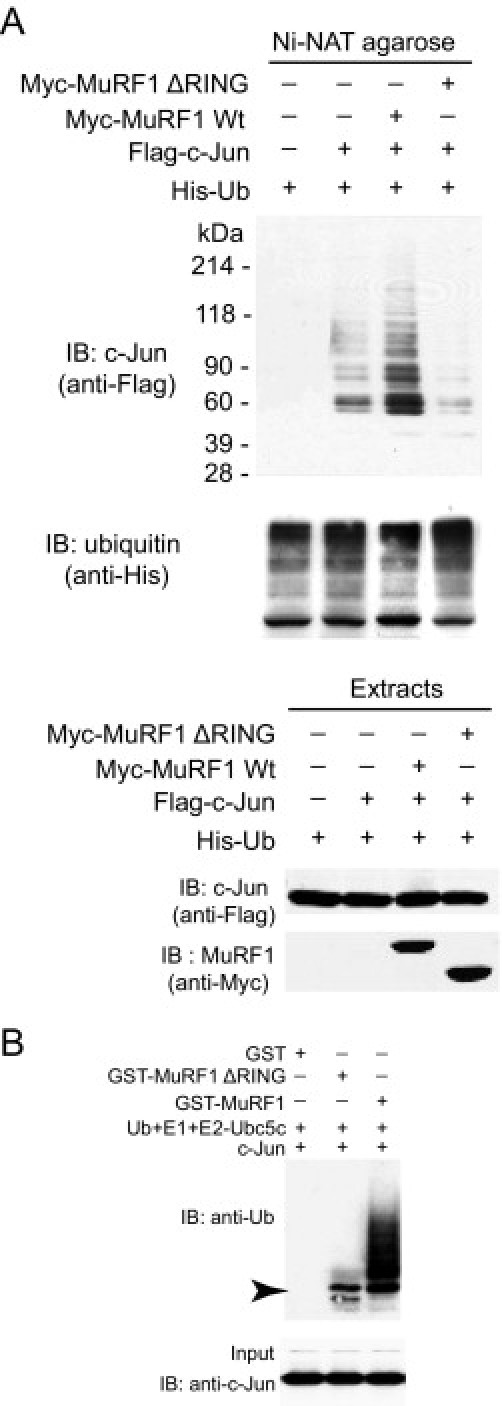

c-Jun Is a Bona Fide Substrate for MuRF1 Ubiquitination

MuRF1's regulation of AP-1 activity through its RING finger domain raised the question of whether MuRF1's ubiquitin ligase activity participated in the targeted degradation of c-Jun by ubiquitinating it. To answer this question, we investigated whether MuRF1 ubiquitinates c-Jun in cell and cell-free systems. Co-transfection of HEK293T cells with tagged MuRF1, c-Jun, and ubiquitin demonstrated that increasing MuRF1 levels enhanced c-Jun ubiquitination (Figure 5A). This enhanced c-Jun ubiquitination was attenuated when MuRF1 lacking the RING domain (with its ubiquitin ligase activity) was co-transfected with tagged c-Jun and ubiquitin, indicating the role of MuRF1's ubiquitin ligase activity in c-Jun ubiquitination (Figure 5A). To explore MuRF1's ubiquitination of c-Jun in more detail, we investigated MuRF1's ability to ubiquitinate c-Jun by determining MuRF1's ability to ubiquitinate c-Jun in cell-free systems using purified ubiquitin, E1, E2, MuRF1 (E3), and the substrate c-Jun (Figure 5B). MuRF1 polyubiquitinates c-Jun to a much greater extent than does MuRF1 that is lacking the RING domain (Figure 5B), indicating that c-Jun is a bona fide MuRF1 substrate and that MuRF1's ubiquitin ligase activity found in the RING finger domain is responsible for much of MuRF1's ubiquitination of c-Jun.

Figure 5.

The ubiquitin ligase activity of MuRF1 promotes mixed chain (K48 and K63) c-Jun ubiquitination in cells and in vitro. A: The RING finger domain has previously been shown to have ubiquitin ligase activity, which adds ubiquitin chains to substrates. To determine whether MuRF1's RING finger domain was necessary to ubiquitinate c-Jun, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with c-Jun, MuRF1 (or MuRF1 missing the RING finger domain), and His-tagged ubiquitin as indicated. Cell lysates were affinity purified for ubiquitin using nickel chromatography (which binds His). MuRF1, but not MuRF1 lacking the RING finger domain, ubiquitinates c-Jun in cells (top). B: In vitro studies were performed to determine the types of ubiquitin chains being added to c-Jun by MuRF1. In vitro ubiquitination reactions were performed with purified ubiquitin, E1, the E2-Ubc5c, purified c-Jun, GST-MuRF-1 wt or GST-MuRF1ΔRING or GST alone. Immunoblot analysis of ubiquitin demonstrated that MuRF1 enhanced the ubiquitination of c-Jun (left). The arrow indicates minimum ubiquitination by the MuRF1ΔRING construct.

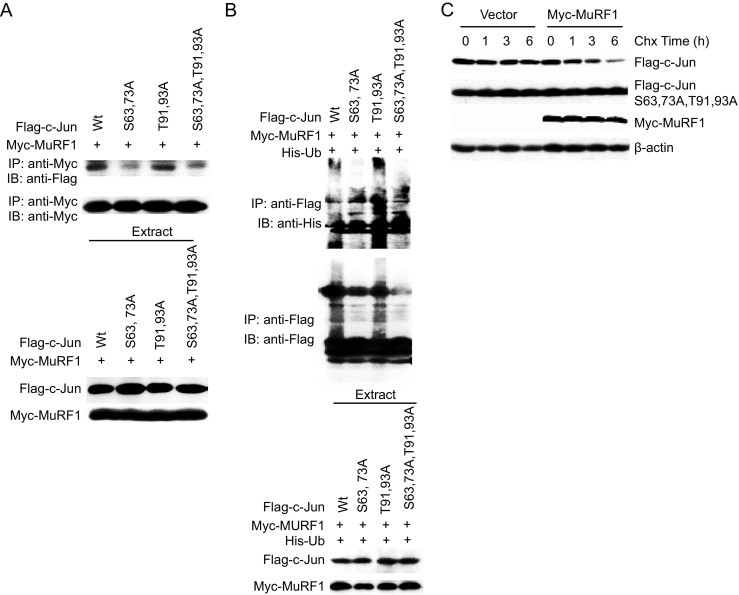

MuRF1 Preferentially Binds p-c-Jun to Enhance Its Ubiquitination and Degradation

The protection that cardiac MuRF1 affords occurs in a very short period after insult (24 hours). This finding made it necessary to explain how MuRF1 preferentially decreased c-Jun levels when activated but not before, at baseline. >One possible explanation is that phosphorylation of c-Jun enhances its recognition as a MuRF1 substrate, which has been shown for other ubiquitin ligases for MAPK signaling substrates.38,47–50 Specifically, JNK itself has ubiquitin ligase activity that recognizes and degrades phosphorylated c-Jun preferentially.51,52 Therefore, we next determined how c-Jun's phosphorylation state changes MuRF1's affinity, downstream ubiquitination, and degradation of c-Jun. Tagged c-Jun, phosphorylation mutant c-Jun constructs, and MuRF1 were transfected in HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitation of MuRF1 was performed to determine its affinity for the different c-Jun phosphorylation mutants after SI/R (Figure 6A). Despite equal expression of wild-type c-Jun and phosphorylation mutant c-Jun constructs, MuRF1 bound c-Jun with S63 and S73 mutations with less affinity (Figure 6A), indicating that these phosphorylation sites may be important, but not absolutely necessary, for MuRF1 to recognize c-Jun as a substrate. In parallel experiments, His-tagged ubiquitin (Ub), MuRF1, and c-Jun phosphorylation mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells, and the amount of c-Jun ubiquitination was determined (Figure 6B). Consistent with MuRF1's decreased affinity for c-Jun with S63 and 73A, decreased c-Jun ubiquitination was identified on S63 and 73A c-Jun phosphorylation mutants (Figure 6B). There seemed to be less dependence on T91 and 93A phosphorylation as MuRF1 ubiquitinated the mutant T91, 93A c-Jun to nearly the same levels of wild-type c-Jun. These findings demonstrate that MuRF1 not only binds p-c-Jun with greater affinity, but it also ubiquitinates c-Jun that is phosphorylated at S63 and/or 73A to a greater extent. This enhanced ubiquitination (found to be both K48 and K63 linked; data not shown) might drive the enhanced recognition and degradation by the proteasome. In this way, MuRF1 preferentially attenuates activated p-c-Jun signaling to quickly counteract the activating signaling through the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathways when they are activated. Because we previously identified that MuRF1 degraded p-c-Jun in a proteasome-dependent manner (Figure 2E), we next determined if c-Jun phosphorylation was necessary for its degradation. One way to enhance signaling through the JNK pathway is to treat cells with cycloheximide, which results in an increase in phosphorylated c-Jun. HEK293T cells were transfected with MuRF1 and either wild-type c-Jun or phosphorylation-resistant c-Jun (c-Jun S63, 73A, T91 93A) and then challenged with cycloheximide to induce c-Jun phosphorylation (Figure 6C). Wild-type c-Jun is rapidly degraded between 1 and 6 hours after cycloheximide treatment; however, the degradation of the phosphorylation mutant c-Jun in parallel studies was completely abolished (Figure 6C). These studies are consistent with a role of MuRF1 in preferentially ubiquitinating activated (phosphorylated) c-Jun and targeting it for degradation by the 26S proteasome to attenuate AP-1 (c-Jun/fos) activity. In this way MuRF1 acts as a negative feedback mechanism to ensure that JNK signaling, leading to cell death, is attenuated during stresses such as I/R injury. This process allows a mechanism for cardiac JNK signaling to be kept in check to balance and control the necessary signaling pathways activated during cardiac stress.

Figure 6.

MuRF1 preferentially binds, ubiquitinates, and degrades phosphorylated c-Jun. A: HEK293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing MuRF1, c-Jun, and phosphorylation site c-Jun mutants. Interactions between MuRF1 and the different phosphorylation mutants were determined by immunoprecipitation. MuRF1 (anti-myc) immunoprecipitation bound wild-type c-Jun preferentially to c-Jun that was unable to be phosphorylated at S63 and 73A determined by immunoblot for c-Jun constructs (anti-FLAG). B: MuRF1's preferential binding of wild type c-Jun compared with S63, 73A mutants parallels MuRF1's ubiquitination of c-Jun. HEK293T cells co-transfected with plasmids expressing His-Ub, Myc-MuRF1, and Flag-c-Jun wild-type or c-Jun phosphorylation mutants as indicated. c-Jun was immunoprecipitated and ubiquitination was determined by immunoblot (top), despite equal expression of c-Jun and c-Jun mutants (bottom). c-Jun mutants lacking their S63, S73 phosphorylation sites are ubiquitinated less by MuRF1 in response to JNK stimulation. C: MuRF1 preferentially degrades c-Jun after its phosphorylation in response to cycloheximide. HEK293T cells were transfected with MuRF1, wild-type c-Jun, and a mutant c-Jun that was unable to be phosphorylated (c-Jun S63, 73A, T91, 93A). By immunoblot, only the wild-type c-Jun that can be phosphorylated is degraded by MuRF1.

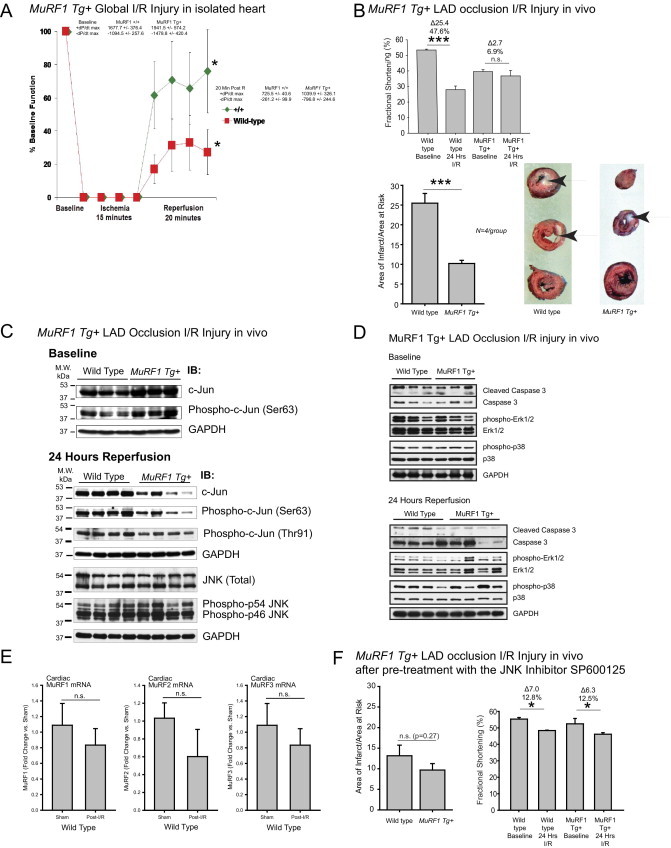

Increased Cardiac MuRF1 Protects Against I/R Injury and Decreases Steady-State Proteins Levels of Phospho-c-Jun in Vivo

To test the relevance of our observations in the intact heart, we examined the effects of MuRF1 on cardiac I/R injury in transgenic (Tg+) mice that have an increased cardiac MuRF1 as recently reported by our laboratory.22 Our in vivo studies focus on the MuRF1 Tg+ mice because of the reported redundancy of MuRF1 with other MuRF family members (MuRF2 and MuRF3) in the heart.17,53,54 Additionally, our in vitro studies identified that MuRF1 interacted with c-Jun through its MFC region, which is a region with a high degree of homology found in MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3. Mice lacking MuRF1 and MuRF253 or MuRF1 and MuRF317 have severe phenotypes that limit their use in I/R studies. We challenged MuRF1 Tg+ mice to two models of cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury: (1) transient global ischemia (15 minutes) followed by 20 minutes of reperfusion (ex vivo); and (2) 30-minute ligation of the LAD coronary artery followed by 24 hours reperfusion (in vivo). Baseline function determined on the isolated MuRF1 Tg+ heart function (eg, developed pressure per time) was not significantly different from wild-type hearts by isovolemic pressure determination of the isolated heart (see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), consistent with previous catheterization studies of the MuRF1 Tg+ mice.22 In response to global ischemia followed by reperfusion in isolated hearts, MuRF1 Tg+ hearts recovered function to a greater degree in ex vivo studies as evidenced by recovery of left ventricular developed pressure (Figure 7A; see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). No differences in % decline and contracture time were identified between MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-type hearts (data not shown), indicating that increasing cardiac MuRF1 did not affect the way Ca2+ was handled during I/R.55

Figure 7.

Mice with increased cardiac MuRF1 exhibit attenuated I/R injury and have an enhanced degradation of cardiac c-Jun in response to I/R in vivo. A: Isolated working hearts from MuRF1 Tg+ and strain-matched wild-type mice were assayed at baseline and after global I/R injury on a Langendorff system. Hearts were allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 minutes, followed by 15 minutes of no-flow ischemia and 20 minutes reperfusion. The recovery of cardiac function (expressed as a % of baseline function) is the fraction of mean left ventricular developed pressure. MuRF1 Tg+ heart recovery trended to improve 20 minutes after perfusion was restarted. (Additional functional parameters are shown in Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org. N = 5 to 6 per group outlined in Supplemental Table 1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). *P < 0.05. B: To determine the durability of this recovery, we challenged MuRF1 Tg+ mice to a 30-minute LAD ischemia injury, followed by a 24-hour recovery in vivo. Determination of the areas of infarct as a fraction of the area at risk demonstrated that MuRF1 Tg+ mice had significant protection against I/R injury in vivo (top). Conscious echocardiography was performed to determine the functional protection of cardiac MuRF1 to I/R injury in vivo. MuRF1 Tg+ mice had significantly less functional deficit compared with wild-type mice determined by fractional shortening (bottom) and EF% (see Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org. N = 6 to 12 mice per group outlined in Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Arrows indicate infarcted area in white. C: Cardiac c-Jun and phospho-cJun in MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-type hearts 24 hours after LAD I/R injury were determined by immunoblot. Significantly less c-Jun and phospho-c-Jun were found in four representative hearts consistent, with its role as a MuRF1 substrate in vivo. N = 3 to 4 hearts per group as indicated in blot. PhosphoSer63-c-jun/total c-jun ratio is the density of the phosphoSer63 c-jun (A.U.) divided by the density of total c-jun (A.U.) to determine the relative phosphorylation of c-jun site associated with activation. D: Cardiac cleaved caspase-3, phospho-ERK1/2/total ERK1/2, phospho-p38/total p38 at baseline and after 30 minutes ischemia and 24 hours reperfusion. E: Real-time PCR analysis of cardiac MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3 mRNA in sham or I/R-challenged wild-type mice 24 hours after surgery. F: Histologic evaluation of cardiac infarction and cardiac function in MuRF1 Tg+ hearts pretreated with the JNK inhibitor SP600125 and challenged with I/R injury (further echocardiographic detail can be found in Supplemental Table S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

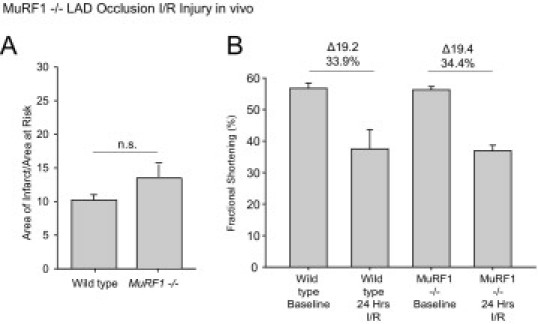

The MuRF1 Tg+ mice also were protected against ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. The cardiac function (fractional shortening) in wild-type hearts decreased 47.6% 24 hours after I/R injury (Figure 7B, top). MuRF1 Tg+ hearts, however, only had a 6.9% decrease in function after I/R injury (Figure 7B, top). Consistent with this protection, MuRF1 Tg+ hearts did not dilate after I/R as much as did wild-type mice (see Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). MuRF1 Tg+ hearts were not only functionally protected, but they had a smaller infarction (measured as a percentage of area at risk) compared with wild-type mice by histology (Figure 7B, bottom). Whereas wild-type hearts had an infarct area of ∼25% (measured as a percentage of the area at risk), MuRF1 Tg+ hearts had an infarct of only ∼10% (Figure 7B, bottom). These results are consistent with our in vitro studies where increasing MuRF1 protects cardiomyocytes from I/R-induced cell death (Figure 1). Because the mechanism of this protection was attributed to the targeted degradation of p-c-Jun in our in vitro studies, we next investigated this mechanism in MuRF1 Tg+ hearts in vivo after I/R injury. In contrast to our in vitro studies, I/R injury in MuRF1−/− mice (previously described by our laboratory)12,13 did not significantly differ at 24 hours (see Supplemental Figure S1 and Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). This finding may be due to the functional redundancy of MuRF1 and MuRF2,54,56 supported by the finding that c-Jun is bound by MuRF1 through its MFC regions, which all family members share.

Because phospho-c-Jun was recognized preferentially by MuRF1 as a substrate, we investigated both total c-Jun and phospho-c-Jun levels in MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-type hearts 24 hours after LAD I/R injury. We found that the MuRF1 Tg+ hearts had decreased phospho-c-Jun 24 hours after reperfusion (Figure 7C, bottom). These differences were not due to differences in the steady-state levels of total c-Jun or phospho-c-Jun found in unchallenged age-matched control hearts (Figure 7C, top). Additionally, we did not identify differences in total or phospho-JNK protein by Western immunoblot, suggesting that the inhibition of phospho-c-Jun was not due to the inhibited signaling upstream of JNK but at the level most proximal to JNK—at the level of c-Jun—consistent with our findings in vitro. We also found that the total c-Jun levels decreased after I/R injury in the MuRF1 Tg+ hearts. No differences in phospho-ERK1/2 or phospho-p38 were identified between MuRF1 Tg+ hearts and wild type at baseline or after 24 hours I/R (Figure 7D). Cleaved caspase 3 by Western blot was decreased after I/R, consistent with the cardioprotection and decreased area of infarction identified in these mice (Figure 7D).

MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3 Levels Do Not Significantly Change After Cardiac I/R Injury in Wild-Type Mice

Understanding the regulation of MuRF1 during ischemia reperfusion would give context to the mechanisms by which MuRF1 protects in wild-type mice. We determined MuRF1 (as well as MuRF2 and MuRF3) mRNA levels in the nonischemic regions in wild-type hearts and found that it did not change significantly 24 hours after I/R in wild-type hearts (Figure 7E). Recent studies investigating how MuRF1 is regulated in human myocardial infarction have identified that MuRF1 significantly decreases in the weeks following insult (<2 weeks).57 When rats undergo myocardial infarction induced by a static LAD artery ligation, MuRF1 has been found to increase at the 7-week time point,58 suggesting that the regulation of MuRF1 may be dynamic in the remodeling process, in part to deal with the changing MAPK signaling pathways.

Pretreatment of MuRF1 Tg+ Mice With a JNK Inhibitor Abolishes the Differential Cardioprotection of Cardiac MuRF1

To determine the significance of JNK signaling in our in vivo model and its role in MuRF1's cardioprotection, we pretreated MuRF1 Tg+ and sibling wild-type control mice with the JNK inhibitor SP600125, as previously described in vivo 31 (Figure 7F). Both wild-type and MuRF1 Tg+ hearts demonstrated an ∼10% infarction size when pretreated with the JNK inhibitor (Figure 7F) compared with the ∼25% infarction size seen in wild type (Figure 7B). Functionally, MuRF1 Tg+ hearts decreased to the same extent as wild-type hearts (Figure 7B; see Supplemental Table S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Discussion

The susceptibility of cardiomyocytes to cell death during I/R injury depends, in part, on cell signaling processes that induce cell death. The signaling pathways most commonly implicated in this process are the MAPK pathways, in particular the p38 and JNK pathways.6,9 The significance of JNK-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocyte I/R injury is highlighted by successful attempts at pharmacologically blocking JNK pathways in experimental cardiac I/R injury to reduce cell death.8,10,11,59 Inhibition of JNK signaling in a number of other organs is protective against I/R injury, including the brain,60 lung,61 kidney,6 and liver.62 In the present study, we identified a novel endogenous cardiac protein (MuRF1) that inhibits JNK signaling by the directed ubiquitination and degradation of activated (phosphorylated) c-Jun to inhibit downstream AP-1 signaling. In this manner, MuRF1 appears to act as a constitutive disposal mechanism by which JNK signaling is buffered by its recognition and destruction of the activated (phosphorylated) c-Jun. These findings compliment our recent studies identifying MuRF1 as an important regulator of other cardiomyocyte transcription factors, including serum response factor, during pathological cardiac hypertrophy.12

In the current study, we found that MuRF1 Tg+ and wild-type cardiac function is not different in the isolated heart. However, we found that by conscious echocardiography we can detect a mild decrease in baseline cardiac function in MuRF1 Tg+ hearts compared with sibling wild-type mice, which is evident by decreases in the fractional shortening (Figure 7B) and ejection fraction (see Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We believe this apparent deficit is due to the stress involved with conscious echocardiography, because isolated heart studies in the present study did not detect a functional defect as demonstrated by ± developed pressure per time (see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Studies inhibiting JNK signaling in the MuRF1 Tg+ mice before I/R demonstrated a reduction in this deficit by conscious echocardiography (Figure 7F; see Supplemental Table S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Despite the complex MuRF1 Tg+ cardiac phenotype, MuRF1's cardioprotection is due, in part, to its regulation of JNK signaling, as these in vivo correlates of our in vitro findings suggest.

Our previous evaluation of the MuRF1 Tg+ mice demonstrated that in the face of pressure overload, MuRF1 Tg+ hearts were more susceptible to failure.22 We found that creatine kinase (CK) activity was decreased, which we hypothesized had to do with the possible turnover of CK. When CK isoenzymes are deleted from the heart, there are serious consequences to cardiac energetics. When the muscle (M) and mitochondrial (Mt) isoforms are deleted, CK−/− mice have an ATP synthesis rate of 9%.63 Inhibiting the flux of phospho-creatinine, the intermediate regulated by CK, either pharmacologically or genetically, enhances the mortality and loss of ATP in the face of myocardial infarction.64,65 These studies demonstrate the importance of CK in ischemic injury; however, the MuRF1 Tg+ hearts do not have a deficit in function after I/R injury. There is not a reason to believe, then, that MuRF1's affects on CK activity would be responsible for protecting against I/R injury. However, we also believe that MuRF1's inhibition of JNK signaling (via c-Jun) is just one mechanism by which our MuRF1 Tg+ mouse model is protected in I/R and that other mechanisms have yet to be identified.

In response to coronary artery occlusion and I/R injury, cell death occurs by multiple cell death pathways, including apoptosis and necrosis, and has been associated with autophagy.66 In our in vitro systems, we see that much of the observed cell death can be detected by TUNEL staining, which can be increased in apoptosis. However, TUNEL staining also can detect changes seen with necrosis and other repair mechanisms, whereby necrosis initiates some of the apoptosis machinery.67,68 This finding might explain the apparent disconnect in our in vitro studies and our in vivo studies, because our in vivo studies demonstrate little cleaved caspase 3 protection in MuRF1 Tg+ hearts (Figure 7E), in contrast with the considerable protection from infarction histologically (Figure 7E). These findings support the growing appreciation for the role of necrosis in I/R injury. While much has been studied on cell death and apoptosis that is activated by MAPK signaling, including JNK,6,9 newer studies have found that apoptosis is not the only downstream process that MAPK signaling regulates. Pro-survival pathways also are stimulated by MAPK,69,70 including JNK in the face of particular cardiomyocyte stresses,71 including reactive oxygen species.72 Careful consideration of these alternative pro-survival MAPK signaling pathways should be made when determining the benefits of inhibiting specific pathways.

In the present study, we identified that MuRF1 interacted with c-Jun through its MFC region.46 The MFC is a highly conserved region in MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3 proteins, suggesting that any of these proteins may regulate c-Jun. We believe it is because of this redundancy that we were unable to identify any phenotype in MuRF1−/− mice (see Supplemental Figure S1 and Supplemental Table S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), but we could in the MuRF1 Tg+ mice. Given the complex phenotype and developmental defects found in MuRF1/3 and MuRF1/2 double-null mice, further testing of this hypothesis was not feasible in vivo. This redundancy does not seem to apply to our H9C2 cell culture model, where siRNA MuRF1 enhanced SI/R cell death. Differences between the MuRF1−/− mice and the MuRF1 siRNA in H9C2 cells may be explained by the differential regulation of these complimentary MuRF family proteins. In the intact mouse heart, MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3 do not change after I/R (Figure 7E), whereas MuRF2 is significantly increased in the rat H9C2 cells after SI/R (Figure 1G). There may even be regional differences in MuRF1 activity, because the H9C2 cells are atrial cardiac derived cells and the experiments in the intact mouse hearts only look at ventricular responses. More work is needed to completely understand the interplay of the MuRF family proteins and their regulation in I/R injury, which may be species and/or cell type specific.

After 24 hours of I/R injury, hearts from MuRF1 Tg+ mice had a decrease in total c-Jun compared with baseline. This finding was different from our in vitro studies in which total c-Jun levels were unaffected by increases in MuRF1. One explanation for this may be the differences in the magnitude of MuRF1 expression in the two systems or the amount of c-Jun that was activated/phosphorylated by the different models of stress. The MuRF1 Tg+ hearts have a 45-fold increase in endogenous MuRF1, which is considerably more than could be achieved in our in vitro systems. This enhanced ubiquitin ligase (MuRF1) expression may lead to greater ubiquitination of the phosphorylated c-Jun, which degrades a greater proportion of the total c-Jun. Our in vivo I/R injury also may enhance c-Jun phosphorylation to a much greater extent because it is a no-flow ischemic event, making it preferentially ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation. Either way, these findings are consistent with the mechanisms we identified in our in vitro studies, where I/R injury induces c-Jun phosphorylation, making it a substrate for MuRF1, which then ubiquitinates it, targeting it for degradation by the proteasome. Because JNK signaling through c-Jun is responsible for activating cell death pathways, the cardioprotection afforded the MuRF1 Tg+ hearts may be due, in part, to the inhibition of JNK signaling we identified. Experimentally, inhibiting c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase (JNK) signaling significantly reduces cardiac I/R injury and infarct size in vivo,10,11,59 indicating JNK's key role in mediating I/R injury. However, MuRF1 interacts with a host of substrates that regulate protein turnover and metabolism, so MuRF1's inhibition of JNK signaling may only partially explain its cardioprotective mechanisms in vivo.

Previous studies mapping MuRF1's interaction with its substrates have identified several unique regions. MuRF1's interaction with troponin I occurs through the coiled-coil region,16 whereas the interaction with muscle CK occurs through its B-box region.73 This finding contrasts with that of the present study, which found that MuRF1 binds c-Jun by its MFC region, a region with nearly complete homology between MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3.46 MuRF1, MuRF2, and MuRF3 are all found in close proximity to each other in the cardiomyocyte sarcomere and cytoplasmol.14,15,46 Recent studies highlight how MuRF1 may be redundant with the remaining members MuRF2 and MuRF3.17,53,54 Both MuRF1 and MuRF2 interact with a specific subset of myofibrillar proteins,54 as do MuRF1 and MuRF3.17 Studies knocking out more than one of the MuRF family members demonstrate hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy (MuRF1/MuRF2 DKO)53 and cardiomyopathy with an increased susceptibility to myocardial infarction (MuRF1/MuRF3 DKO),17 making compound knock-outs impractical to use. It is for this reason that we performed our in vivo experiments in the cardiac MuRF1 Tg+ mice, which allowed us to delineate MuRF1's role in the heart, despite the apparent redundancy between the MuRF family members in the heart.

MuRF1 interacts with many proteins and transcription factors to regulate the turnover of the sarcomere,20 pressure overload–induced cardiac hypertrophy,12 and cardiac atrophy.13 The findings in the present study suggest that MuRF1 preferentially recognizes, ubiquitinates, and degrades phosphorylated c-Jun to regulate its activity to fundamentally regulate, in part, the pathophysiology of I/R injury. However, the downstream cardioprotection seen in our in vivo experiments may be due only in part to the inhibition of JNK signaling. To fully understand how MuRF1 might be cardioprotective in ischemia reperfusion injury, we will need to understand more fully the spectrum of mechanisms by which MuRF1 protects the heart in vivo.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the China Natural Science Foundation (81025001 to H.-H.L. and 2006CB503801 to D.-P.L.); the Beijing high-level talents program (PHR20110507 to H.L.); the American Heart Association (Scientist Development grant to M.S.W.); and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01HL104129 to M.S.W.). Work was performed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and at Peking Union Medical College, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

None of the authors disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjapthol.org or at doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.049.

Contributor Information

Hui-Hua Li, Email: hhli1935@yahoo.cn.

Monte S. Willis, Email: monte_willis@med.unc.edu.

Supplementary data

Supplemental Figure 1.

MuRF1−/− mice were challenged to a 30-minute left anterior descending (LAD) ischemia injury, followed by a 24-hour recovery in vivo. A: Determination of the areas of infarct as a fraction of the area at risk demonstrated that MuRF1−/− mice were not significantly protected against I/R injury in vivo. Conscious echocardiography was performed to determine the functional protection of cardiac MuRF1 to I/R injury in vivo. MuRF1−/− mice were not significantly protected functionally compared with wild-type mice determined by fractional shortening (bottom) and EF% (see Supplemental Table S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org; N = 5-7 per group as outlined in Supplemental Table S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

References

- 1.Maxwell S.R., Lip G.Y. Reperfusion injury: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and therapeutic options. Int J Cardiol. 1997;58:95–117. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(96)02854-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laderoute K.R., Webster K.A. Hypoxia/reoxygenation stimulates Jun kinase activity through redox signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1997;80:336–344. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seko Y., Takahashi N., Tobe K., Kadowaki T., Yazaki Y. Hypoxia and hypoxia/reoxygenation activate p65PAK, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:840–844. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight R.J., Buxton D.B. Stimulation of c-Jun kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase by ischemia and reperfusion in the perfused rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:83–88. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizukami Y., Yoshioka K., Morimoto S., Yoshida K. A novel mechanism of JNK1 activation: Nuclear translocation and activation of JNK1 during ischemia and reperfusion. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16657–16662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin T., Sandhu G., Wolfgang C.D., Burrier A., Webb R.L., Rigel D.F., Hai T., Whelan J. Tissue-specific pattern of stress kinase activation in ischemic/reperfused heart and kidney. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19943–19950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fryer R.M., Patel H.H., Hsu A.K., Gross G.J. Stress-activated protein kinase phosphorylation during cardioprotection in the ischemic myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1184–H1192. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yue T.L., Wang C., Gu J.L., Ma X.L., Kumar S., Lee J.C., Feuerstein G.Z., Thomas H., Maleeff B., Ohlstein E.H. Inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase enhances Ischemia/Reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in cultured cardiac myocytes and exaggerates reperfusion injury in isolated perfused heart. Circ Res. 2000;86:692–699. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.6.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugden P.H., Clerk A. “Stress-responsive” mitogen-activated protein kinases (c-Jun N-terminal kinases and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases) in the myocardium. Circ Res. 1998;83:345–352. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrandi C., Ballerio R., Gaillard P., Giachetti C., Carboni S., Vitte P.A., Gotteland J.P., Cirillo R. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase decreases cardiomyocyte apoptosis and infarct size after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:953–960. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milano G., Morel S., Bonny C., Samaja M., von Segesser L.K., Nicod P., Vassalli G. A peptide inhibitor of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and infarct size in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1828–H1835. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01117.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willis M.S., Ike C., Li L., Wang D.Z., Glass D.J., Patterson C. Muscle ring finger 1, but not muscle ring finger 2, regulates cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res. 2007;100:456–459. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259559.48597.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willis M.S., Rojas M., Li L., Selzman C.H., Tang R.H., Stansfield W.E., Rodriguez J.E., Glass D.J., Patterson C. Muscle ring finger 1 mediates cardiac atrophy in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H997–H1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00660.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arya R., Kedar V., Hwang J.R., McDonough H., Li H.H., Taylor J., Patterson C. Muscle ring finger protein-1 inhibits PKC{epsilon} activation and prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1147–1159. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mrosek M., Labeit D., Witt S., Heerklotz H., von Castelmur E., Labeit S., Mayans O. Molecular determinants for the recruitment of the ubiquitin-ligase MuRF-1 onto M-line titin. FASEB J. 2007;21:1383–1392. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7644com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kedar V., McDonough H., Arya R., Li H.H., Rockman H.A., Patterson C. Muscle-specific RING finger 1 is a bona fide ubiquitin ligase that degrades cardiac troponin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18135–18140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404341102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fielitz J., Kim M.S., Shelton J.M., Latif S., Spencer J.A., Glass D.J., Richardson J.A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E.N. Myosin accumulation and striated muscle myopathy result from the loss of muscle RING finger 1 and 3. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2486–2495. doi: 10.1172/JCI32827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen S., Brault J.J., Gygi S.P., Glass D.J., Valenzuela D.M., Gartner C., Latres E., Goldberg A.L. During muscle atrophy, thick, but not thin, filament components are degraded by MuRF1-dependent ubiquitylation. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:1083–1095. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willis M.S., Schisler J.C., Patterson C. Appetite for destruction: e3 ubiquitin-ligase protection in cardiac disease. Future Cardiol. 2008;4:65–75. doi: 10.2217/14796678.4.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis M.S., Schisler J.C., Portbury A.L., Patterson C. Build it up-tear it down: protein quality control in the cardiac sarcomere. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:439–448. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammerding J., Kamm R.D., Lee R.T. Mechanotransduction in cardiac myocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:53–70. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willis M.S., Schisler J.C., Li L., Rodriguez J.E., Hilliard E.G., Charles P.C., Patterson C. Cardiac muscle ring finger-1 increases susceptibility to heart failure in vivo. Circ Res. 2009;105:80–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H.H., Kedar V., Zhang C., McDonough H., Arya R., Wang D.Z., Patterson C. Atrogin-1/muscle atrophy F-box inhibits calcineurin-dependent cardiac hypertrophy by participating in an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1058–1071. doi: 10.1172/JCI22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Z., Zhong H., Bosch-Marce M., Fox-Talbot K., Wang L., Wei C., Trush M.A., Semenza G.L. Complete loss of ischaemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mice with partial deficiency of HIF-1 alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:463–470. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwencke C., Schmeisser A., Walter C., Wachter R., Pannach S., Weck B., Braun-Dullaeus R.C., Kasper M., Strasser R.H. Decreased caveolin-1 in atheroma: loss of antiproliferative control of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuoka S., Moriyama T., Ohara N., Tanimura K., Maruo T. Caffeine induces apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells through the caspase-9 pathway. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:48–53. doi: 10.1080/09513590500476198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie P., Guo S., Fan Y., Zhang H., Gu D., Li H. Atrogin-1/MAFbx enhances simulated ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes through degradation of MAPK phosphatase-1 and sustained JNK activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5488–5496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett B.L., Sasaki D.T., Murray B.W., O'Leary E.C., Sakata S.T., Xu W., Leisten J.C., Motiwala A., Pierce S., Satoh Y., Bhagwat S.S., Manning A.M., Anderson D.W. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson S.M., Morange M. Hsp25 and the p38 MAPK pathway are involved in differentiation of cardiomyocytes. Dev Biol. 2000;218:146–160. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue T.L., Gu J.L., Wang C., Reith A.D., Lee J.C., Mirabile R.C., Kreutz R., Wang Y., Maleeff B., Parsons A.A., Ohlstein E.H. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase plays an essential role in hypertrophic agonists, endothelin-1 and phenylephrine-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37895–37901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J., Li X.X., Bian H.J., Liu X.B., Ji X.P., Zhang Y. Inhibition of the activity of Rho-kinase reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis in heart ischemia/reperfusion via suppressing JNK-mediated AIF translocation. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;401:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H.H., Willis M.S., Lockyer P., Miller N., McDonough H., Glass D.J., Patterson C. Atrogin-1 inhibits Akt-dependent cardiac hypertrophy in mice via ubiquitin-dependent coactivation of Forkhead proteins. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3211–3223. doi: 10.1172/JCI31757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hampton T.G., Amende I., Fong J., Laubach V.E., Li J., Metais C., Simons M. Basic FGF reduces stunning via a NOS2-dependent pathway in coronary-perfused mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H260–H268. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hampton T.G., Amende I., Travers K.E., Morgan J.P. Intracellular calcium dynamics in mouse model of myocardial stunning. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1821–H1827. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Min J.Y., Hampton T.G., Wang J.F., DeAngelis J., Morgan J.P. Depressed tolerance to fluorocarbon-simulated ischemia in failing myocardium due to impaired [Ca(2+)] (i) modulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1446–H1456. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.5.H1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinciguerra M., Esposito I., Salzano S., Madeo A., Nagel G., Maggiolini M., Gallo A., Musti A.M. Negative charged threonine 95 of c-Jun is essential for c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent phosphorylation of threonine 91/93 and stress-induced c-Jun biological activity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kielosto M., Nummela P., Katainen R., Leaner V., Birrer M.J., Holtta E. Reversible regulation of the transformed phenotype of ornithine decarboxylase- and ras-overexpressing cells by dominant-negative mutants of c-Jun. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3772–3779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-3188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laine A., Ronai Z. Ubiquitin chains in the ladder of MAPK signaling. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2812005re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vesely P.W., Staber P.B., Hoefler G., Kenner L. Translational regulation mechanisms of AP-1 proteins. Mutat Res. 2009;682:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodine S.C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V.K., Nunez L., Clarke B.A., Poueymirou W.T., Panaro F.J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z.Q., Valenzuela D.M., DeChiara T.M., Stitt T.N., Yancopoulos G.D., Glass D.J. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aoki H., Kang P.M., Hampe J., Yoshimura K., Noma T., Matsuzaki M., Izumo S. Direct activation of mitochondrial apoptosis machinery by c-Jun N-terminal kinase in adult cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10244–10250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartling B., Holtz J., Darmer D. Contribution of myocyte apoptosis to myocardial infarction? Basic Res Cardiol. 1998;93:71–84. doi: 10.1007/s003950050065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottlieb R.A., Burleson K.O., Kloner R.A., Babior B.M., Engler R.L. Reperfusion injury induces apoptosis in rabbit cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1621–1628. doi: 10.1172/JCI117504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olivetti G., Abbi R., Quaini F., Kajstura J., Cheng W., Nitahara J.A., Quaini E., Di Loreto C., Beltrami C.A., Krajewski S., Reed J.C., Anversa P. Apoptosis in the failing human heart. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1131–1141. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schumann H., Morawietz H., Hakim K., Zerkowski H.R., Eschenhagen T., Holtz J., Darmer D. Alternative splicing of the primary Fas transcript generating soluble Fas antagonists is suppressed in the failing human ventricular myocardium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:794–798. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centner T., Yano J., Kimura E., McElhinny A.S., Pelin K., Witt C.C., Bang M.L., Trombitas K., Granzier H., Gregorio C.C., Sorimachi H., Labeit S. Identification of muscle specific ring finger proteins as potential regulators of the titin kinase domain. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:717–726. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu S., Robbins D., Frost J., Dang A., Lange-Carter C., Cobb M.H. MEKK1 phosphorylates MEK1 and MEK2 but does not cause activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6808–6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Witowsky J.A., Johnson G.L. Ubiquitylation of MEKK1 inhibits its phosphorylation of MKK1 and MKK4 and activation of the ERK1/2 and JNK pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1403–1406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu Z., Xu S., Joazeiro C., Cobb M.H., Hunter T. The PHD domain of MEKK1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of ERK1/2. Mol Cell. 2002;9:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deak J.C., Templeton D.J. Regulation of the activity of MEK kinase 1 (MEKK1) by autophosphorylation within the kinase activation domain. Biochem J. 1997;322(Pt 1):185–192. doi: 10.1042/bj3220185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuchs S.Y., Dolan L., Davis R.J., Ronai Z. Phosphorylation-dependent targeting of c-Jun ubiquitination by Jun N-kinase. Oncogene. 1996;13:1531–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Musti A.M., Treier M., Bohmann D. Reduced ubiquitin-dependent degradation of c-Jun after phosphorylation by MAP kinases. Science. 1997;275:400–402. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Witt C.C., Witt S.H., Lerche S., Labeit D., Back W., Labeit S. Cooperative control of striated muscle mass and metabolism by MuRF1 and MuRF2. EMBO J. 2008;27:350–360. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Witt S.H., Granzier H., Witt C.C., Labeit S. MURF-1 and MURF-2 target a specific subset of myofibrillar proteins redundantly: towards understanding MURF-dependent muscle ubiquitination. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koyama T., Temma K., Akera T. Reperfusion-induced contracture develops with a decreasing [Ca2+]i in single heart cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1115–H1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez J.E., Li L., Lockyer P., Patterson C., Willis M.S. Spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy results from the loss of Muscle Ring Finger 1 and 2. FASEB J. 2008;22(Meeting Abstract Suppl):466.11. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conraads V.M., Vrints C.J., Rodrigus I.E., Hoymans V.Y., Van Craenenbroeck E.M., Bosmans J., Claeys M.J., Van Herck P., Linke A., Schuler G., Adams V. Depressed expression of MuRF1 and MAFbx in areas remote of recent myocardial infarction: a mechanism contributing to myocardial remodeling? Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adams V., Linke A., Gielen S., Erbs S., Hambrecht R., Schuler G. Modulation of Murf-1 and MAFbx expression in the myocardium by physical exercise training. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:293–299. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f3ec43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wen J., Watanabe K., Ma M., Yamaguchi K., Tachikawa H., Kodama M., Aizawa Y. Edaravone inhibits JNK-c-Jun pathway and restores anti-oxidative defense after ischemia-reperfusion injury in aged rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:713–718. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haeusgen W., Boehm R., Zhao Y., Herdegen T., Waetzig V. Specific activities of individual c-Jun N-terminal kinases in the brain. Neuroscience. 2009;161:951–959. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang X., Bedard E.L., Potter R., Zhong R., Alam J., Choi A.M., Lee P.J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases regulate HO-1 gene transcription after ischemia-reperfusion lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L815–L829. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00485.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bendinelli P., Piccoletti R., Maroni P., Bernelli-Zazzera A. The MAP kinase cascades are activated during post-ischemic liver reperfusion. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saupe K.W., Spindler M., Tian R., Ingwall J.S. Impaired cardiac energetics in mice lacking muscle-specific isoenzymes of creatine kinase. Circ Res. 1998;82:898–907. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.ten Hove M., Lygate C.A., Fischer A., Schneider J.E., Sang A.E., Hulbert K., Sebag-Montefiore L., Watkins H., Clarke K., Isbrandt D., Wallis J., Neubauer S. Reduced inotropic reserve and increased susceptibility to cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury in phosphocreatine-deficient guanidinoacetate-N-methyltransferase-knockout mice. Circulation. 2005;111:2477–2485. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165147.99592.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horn M., Remkes H., Stromer H., Dienesch C., Neubauer S. Chronic phosphocreatine depletion by the creatine analogue beta-guanidinopropionate is associated with increased mortality and loss of ATP in rats after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:1844–1849. doi: 10.1161/hc3901.095933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whelan R.S., Kaplinskiy V., Kitsis R.N. Cell death in the pathogenesis of heart disease: mechanisms and significance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:19–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kockx M.M., Muhring J., Knaapen M.W., de Meyer G.R. RNA synthesis and splicing interferes with DNA in situ end labeling techniques used to detect apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:885–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]